The Sunday Post for March 8, 2020

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights just a few things we loved reading and want to share with you. Settle in with a cup of coffee, or tea, if that's your pleasure — we saved you a seat! Read an essay or an article online that you loved? Let us know at submissions@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Need more browse? You can also look through the archives.

This Sunday, three fascinating examples of storytelling with data and charts, from literary geographies of well-known authors to mapping time in Antebellum American history books:

Do authors write where their know?

My dream is to be multi-talented enough to work for Pudding.cool, but alas, I am just a devoted reader for now. This data story uses geographical information from the author’s life and the settings of their books to find out which authors really “write what they know,” down to the mile. It also does deep dives on prominent authors like Kazuo Ishiguro, a product of early emigration to Britain, writing about the preserved Japan of his childhood, and Toni Morrison, who uses her hometown of Ohio to represent an escape from the ghetto. I would say read on, but really you’ll want to click around:

Ishiguro’s family immigrated to Britain from Japan when he was only five years old. In his wonderful 2017 Nobel lecture, he outlines his experiences grappling with his identity in relation to his geocultural roots, both as a child and an adult. He cites as a pivotal moment in his literary career the night he found himself “writing, with a new and urgent intensity, about Japan” after a few weeks of attempting to set a story in Britain. That night sparked a journey that would turn into his first novel A Pale View of Hills. The book, he says, was his way of preserving a Japan that was borne of and existed only in his mind, “to which (he) in some way belonged, and from which (his) drew a certain sense of (his) identity.”

Tracing the world’s four oldest fairy tales

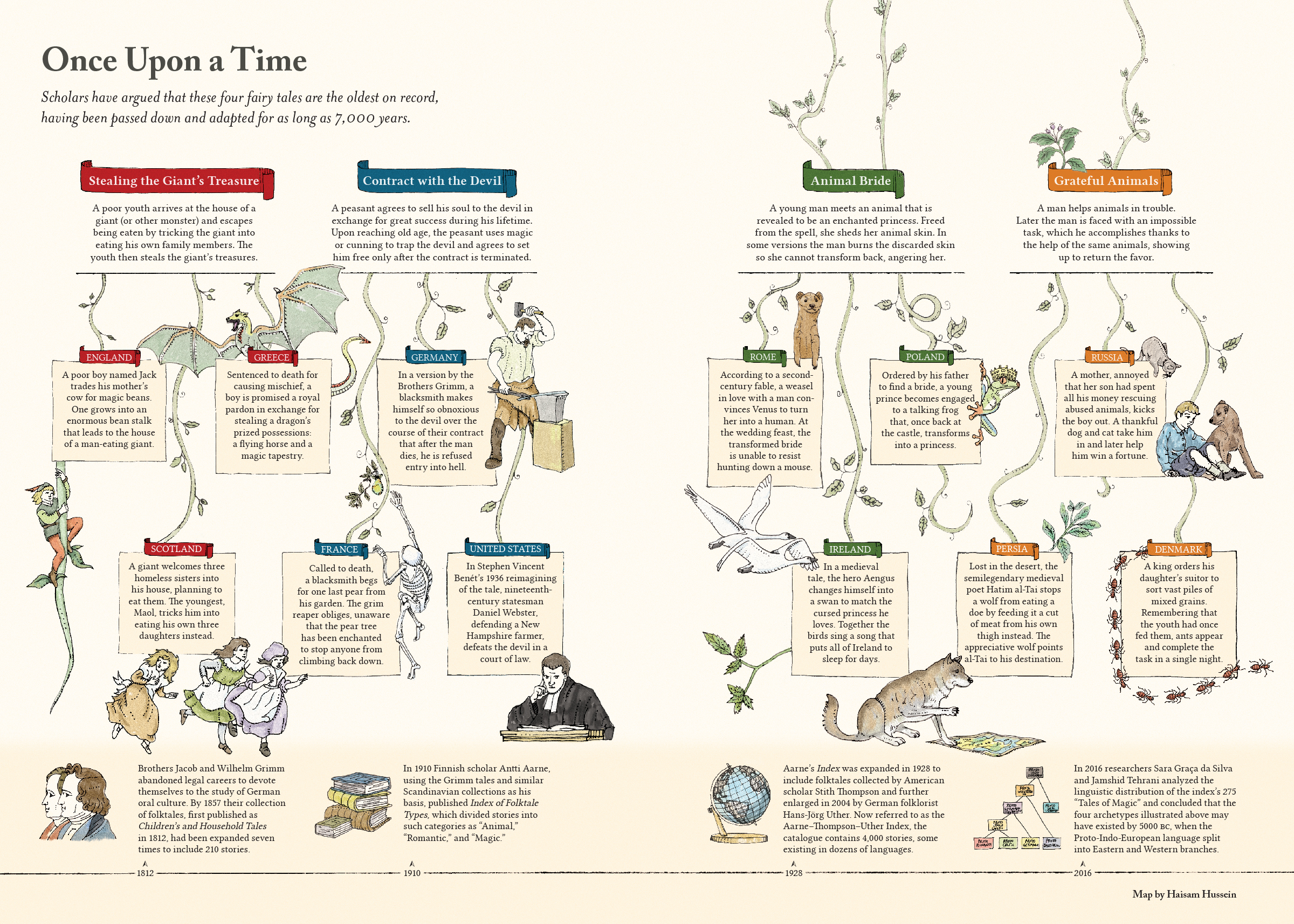

Fairy tales were just bright, musical Disney films until I received a hardback version of Grimm’s when I was eight. They were...grim — I didn’t like them. In college, I read Robert Darnton’s The Great Cat Massacre, and learned that the reason these stories felt so dark was because they were first and foremost morality tales designed to scare young children into submission. Apparently an early version of “The Little Red Riding Hood” ended with the Wolf persuading the child to get in naked in bed with him — yikes! Lapham’s Quarterly traces all fairy tales back to just four archetypes:

Emma Willard's Maps of Time

Emma Willard, a feminist educator, pioneered the visual display of history, and her beautiful, though teleological, timelines turned history into cartographies. Here’s a great essay from one of my favorite online magazines that considers at the ways in which her sense of history — a march of progress, showed up in those thoughtful, curious timelines that influenced a generation of American history books:

All of North America’s colonial history merely formed the backstory to the preordained rise of the United States. The [Tree of Time] also strengthened a sense of coherence, organizing the chaotic past into a series of branches that spelled out the national meaning of the past. Above all, the Tree of Time conveyed to students a sense that history moved in a meaningful direction. Imperialism, dispossession, and violence was translated, in Willard’s representation, into a peaceful and unified picture of American progress.