Once upon a time

Published October 09, 2018, at 11:48am

In her latest collection of short stories, Seattle's smartest writer, Rebecca Brown, has turned her big brain to something elemental, entertaining, and maybe a little bit dangerous.

Just for Tonight, Walking Home in Rain

We’ll begin at the end —

move backwards toward the flickering light

that catches our skin like a spark.

I’ll call all men sweethearts

as their slim suits speed towards me through time.I’ll wear furs and smoke long cigarettes

and you’ll snap your thin suspenders

when you’re pleased with yourself,

swing your coat over your left shoulder

like a baseball bat.I’ll speak from an octave lower in my throat,

sing a bluesy note from time to time,

kiss the air around your head

as if everything about you

is a soft place to land.You’ll be tough and unwavering —

like the shadow of a stone,but no matter the bind it puts you in,

it won’t take long for you to turn

towards my legs as if

they were long strands of rope.Just for tonight,

we won’t care who done it,

or wonder how we’ve arrivedat the edge of the pool,

looking down at the body

floating as bodies do in old movies,

or wonder which of us did this,

or which of us is already dead.

Medusa faces the courthouse

Note: this essay discusses the story of Medusa, which includes mentions of rape. Reader discretion advised. Illustration by Christine Marie Larsen

You know the story of Medusa: Perseus beheaded her. Athena lent him her polished shield, which acted as mirror so he could look upon the reflection of the snake-haired Gorgon monster. Other men, looking directly at her, were turned to stone, and Pereus walked among that macabre statuary to find her. This is the story told most, the hero’s part in slaying the monster.

But did you know that Medusa was born human? She had two Gorgon sisters, who, depending on the telling, were born monsters or, like Medusa, born human. Medusa herself was said to be beautiful.

So spoke Perseus himself, in the fourth book of Ovid’s Metamorphases, here translated in the 18th century by Sir Samuel Garth:

Medusa once had charms; to gain her love

A rival crowd of envious lovers strove.

They, who have seen her, own, they ne'er did trace

More moving features in a sweeter face.

Yet above all, her length of hair, they own,

In golden ringlets wav'd, and graceful shone.

She pledged herself to Athena, one of the virgin gods. So, young Medusa’s pledge meant that she, too, was to remain virgin in honor of her goddess. But as the above passage shows, Medusa was not left at peace by men: “a rival crowd of envious lovers strove.”

She turned them all away, the strivers. One she turned away was a god: Poseidon. The privilege of gods is to not listen to the consent of humans. He raped her. Because he despised Athena for denying him Medusa, he raped her in Athena’s temple. Athena was said to look away.

In a just story, Athena would have brought her wrath down on her fellow god. She would have come to Medusa and favored her, for Medusa did her best to remain faithful to Athena, and did not willingly break the pledge. Athena, in a just story, would have worked to heal Medusa from her trauma.

One telling has the young Medusa weeping at the temple and begging the forgiveness of the goddess she so admired. “Forgive me, Athena!” She said, the victim asking for forgiveness, as if it is her own fault.

But Athena was not merciful. She ignored the rapist Poseidon, and turned her wrath instead on Medusa. For her sin of being a victim, Athena turned her hideous. Her luscious hair was turned to snakes. Her gaze was made to turn men to stone. She was banished to a faraway island.

There she lived with her monstrous sisters. Men, as always, came to her, but now they came to kill, to gain a trophy and glory. All of them fell under her gaze, and were frozen in place, never to move again. Until, that is, Perseus arrived.

Remember, he arrived aided by the same goddess who banished Medusa to her lonely, sad, brutal existence. Athena lent him the shield that allowed him to approach Medusa without directly gazing upon her, and so he was spared the fate of those who came before.

And some time after he took her head away as trophy — her drops of blood casting snakes upon the land he flew over, wearing Hermes’ winged sandals — Athena gained possession of the decapitated head of her once acolyte.

The virgin goddess took the head of Medusa and attached it to the shield Perseus had used to outwit the power of Medusa’s sight. She mounted the head, and forever more when she would go into battle, the head would scream a terrible roar that turned the blood of Athena’s enemies ice-cold.

The name of this shield is the “Aegis”, a word that now means to be under the protection or support of a more powerful person or organization. I wonder what Medusa might think, were she real, of this cruelly ironic derivative of the original meaning.

I can’t stop thinking about Medusa today, she who was assaulted and humiliated, and then after was treated with cruelty, contempt, and vicious attack. She was turned monster not by action of her own, but by those who made her victim, cast her aside, and then, after doing so, made the sadistic choice to never let her have a moment of peace, and after, used her effigy to terrify their enemies. How they created the monster and used the monster, which had nothing to do with the actions of the woman they cursed.

Were she to stand, today, in front of the Supreme Court, she would recognize its facade. How it resembles Athena’s temple. She would recognize in the frieze Liberty, flanked by Order and Authority, and in statuary, Justice herself (presented as a model, a toy, held by a towering woman in flowing classical robes, reading a codex, paying Justice no heed), all of them cast in stone, as if gazed on by Medusa at the height of her haunting. Justice, Liberty, Order, Authority, symbolically congealed in marble by chisel, unable to act. She could tell, one assumes, how the men that made this building feign worship at ideals that are invoked in rhetoric, but are toothless and inanimate as Carrara rock when betrayed.

She would recognize the women standing around her, defeated. Looking up at this building in disbelief, looking at an aegis who protects those who assault the liberty of others. Those who ask for their elected representatives to be the aegis of the people, and who, again and again, are denied this right, and then cast as monster for even asking to be seen, heard, and believed.

How she would recognize, so rightly, their brutal rage, their righteous anger, their desire for a modicum of justice. How she would weep and wail with them, and perhaps tell her own story about Poseidon, sitting inside in freshly sewn robes.

Sitting inside drinking a beer, occasionally too many, but never to the point of blacking out. He doesn’t even remember being at the temple of Athena. Other gods can vouch for him. He is not accusing Medusa of lying. He’s just sure she’s confusing him with somebody else. He's so sorry for what's happened to her, but it had nothing to do with him.

And now a word from our sponsor

The topic is on the nose right now. At first glance a thriller, Death by the River is more truly a call to action, Weis says: "like the girls victimized by Beau Devereaux, women can band together, fight back, and get justice. We have a voice."

Visit our sponsor feature page to read more about the book and its conception, and check out an excerpt.

Sponsors like Vesuvian Books make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? There's only ONE slot remaining in our fall/winter block, for the week of January 21. Grab it fast, and be one of the first books (or events) our readers see in 2019! Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from October 8th - October 14th

Monday, October 8: Everyday People Reading

Jennifer Baker is the editor of a short story anthology titled Everyday People: The Color of Life. Tonight, she's presenting the book with Seattle contributors including Anastacia-Renee, Dennis Norris II, and Jessica Rycheal. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, October 9: Four Poets

We are big fans of Seattle poet E.J. Koh. Tonight, she reads with three other poets including Keegan Lester, Carly Jo Miller, and the delightful Jane Wong. Think of this as your Lit Crawl pre-funk. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Wednesday, October 10: A Year of Living Kindly Reading

Look: try to be kind, okay? Donna Cameron's new book is about changing the world through small acts of kindness. I know this feels like lunacy in a world with egregious acts of unkindness happening all around us at all times, but maybe that's exactly why it's important to think about kindness right now. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, October 11: Lit Crawl

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Everywhere. 6 pm - late.Friday, October 12: Terrible blooms reading

San Francisco writer Melissa Stein's latest poetry collection, Terrible blooms, was published by Port Townsend's own Copper Canyon Press. Stein is joined tonight by wondrous Seattle poet Sarah Galvin. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Saturday, October 13: Pistil Books 25th Anniversary

Pistil Books was a brick-and-mortar bookstore in the Pike/Pine neighborhood (roughly where Bimbo's is today.) They still have a flourishing online bookstore, and they've officially been in business for 25 years, which is a big deal. Tonight, they're celebrating with cake and with readings by Capitol Hill authors Rebecca Brown and Stacey Levine. This will be a good evening for nostalgia and for looking forward. Pistil Books, secret location, please RSVP to pistil@speakeasy.net.

Sunday, October 14: First Mountain Reading

Did you know that a world-class, expert translator of Chinese poetry lives and works in Olympia? Her name is Zhang Er, and her latest book of poetry is titled First Mountain. It was written in Chinese and translated by Zhang Er herself and Joseph Donahue. This afternoon, she reads with Leonard Schwartz, author of Salamander: A Bestiary.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: Three Lit Crawl itineraries

This Thursday is Lit Crawl, the busiest night in the Seattle readings calendar. This year, there are four different readings periods: 6 pm - 6:45, 7 pm - 7:45, 8 pm - 8:45, and 9 pm - 9:45. I thought I'd assemble three possible itineraries for you from the dozens of combinations you could enjoy.

For the Tried and True crawl, full of classic Seattle talent that always delivers, you should start at Hugo House where Rebecca Brown, the smartest writer in Seattle, will read from her new book of stories. Brown will be joined by Richard Chiem, who will be reading from his new novel, and poet JM. Then, stay at Hugo House for a presentation by Frances McCue and Cali Kopczick about the old Hugo House which will also serve as closure for an unfinished event that they put on in the old space. Next, skip over to Barca for a reading from greats including Karen Finneyfrock, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Kamari Bright, and Christine Texeira. Finally, end up at Corvus and Company for a reading from Washington State Poet Laureate Claudia Castro Luna, Samar Abulhassan, Natalie A. Martínez, and Jane Wong.

For Multidisciplinary Madness, begin at Narwhal, where poets and cartoonists will mix media in a presentation from Rachel Kessler, Sierra Nelson, and Gabrielle Bates. Next, the Other Coast Cafe hosts "an evening dip into hybridity," which blurs the line between fiction and fact and prose and poetry with Rezina Habtemariam, Corinne Manning, Kym Littlefield, and Ramon Isao. Then, the Capitol Hill library hosts a reading of sci-fi and fantasy stories written by Ray Bradbury. Finally, at Saint John's, writer Peter Mountford presents two stories about BDSM and talks on the topic of writing about kink.

Finally, for an evening with No Platform for White Men, begin at Cafe Solstice, where Nicole Hardy, Michele Bombardier, Brittney Corrigan, SRoB columnist Clare Johnson, and Rena Priest will celebrate Mineral School. Stay put at Solstice for an evening of women writers (including Frances Chiem, Jessica Mooney, Sally Hedges-Blanquez, and Holly DeBevoise) exploring the metaphysical. Then, the African-American Writers Alliance takes over Roy Street Coffee & Tea with writers like Kathya Alexander and Lola Peters. Finally, at Barca, Gramma Press presents the best in envelope-pushing poetry with Catherine Bresner, Kim Selling, Sarah Galvin, and Mary Anne Carter.

For those of you who do not crumble into ancient dust after going to four events in a single evening, there's an afterparty at Hugo House starting — wheeze — at 10 pm.

Thursday night, various locations, https://www.litquake.org/lit-crawl-seattle.html.

The Sunday Post for October 7, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Brett Kavanaugh and the Information Terrorists Trying to Reshape America

You’ll remember most of the events covered by Molly McKew in this piece — Gamergate, Pizzagate, QAnon — but here’s a chance to see them outside the punch of outrage and understand the social movement that ties them together, a movement that elected Donald Trump and confirmed Brett Kavanaugh. Actually “social movement” is the wrong term: McKew’s point is that the enabler here is a kind of information system that’s entirely new, and which the old systems are entirely unprepared to fight.

This has all taken on a new heady energy as pushback to #MeToo — and riding the coattails of the conspiracy bandwagon. But the intent is the same: to demonize the opponent, define identity, activate the base around emotional rather than rational concepts, and build a narrative that can be used to normalize marginal and radical political views. It is, after all, very convenient to have a narrative positing that all your political opponents are part of a secret cabal of sexual predators, which thus exonerates your side by default.

This is the ideological landscape that has been so swiftly leveraged in the defense of Brett Kavanaugh.

Orthodoxxed!

Now move into Greg Afinogenov’s analysis of the scholarly hoax revealed by its perpetrators last week and aimed at undercutting what the hoaxers call “grievance studies,” which is to say academic studies related to sexism, racism, and other kinds of marginalization. We’ve lost track of the difference between punching up and punching down. A convenient confusion for people terrified of fighting on a level playing field.

The orthodoxy these men represent is not an orthodoxy of scientific legitimacy but rather the emerging consensus of tech bros, Davos billionaires, and alt-right misogynists. Each of these groups has its own reasons to hate feminist and other critical scholarship—whether for ideological reasons, positivist data fetishism, or the perception that they are uncommodifiable and hence worthless. It has thus been easy for them to find common cause in fighting the old Sokal specter of academic postmodernism that supposedly still dominates academia. At stake in the hoax, then, is precisely the question of whether it is “grievance studies” that is Goliath and methodological “common sense” that is David, or vice-versa.

It's OK to Be a Writer and a __

Laurie Patton, college president and poet, debunks the idea that it’s more courageous, or proper, to be solely one or the other. A gentle essay, but resolute against the idea that there’s anything a “real” writer does or doesn’t do.

The Tanpura Principle in writing is the idea that much of writing occurs while doing something else, because the base of poetic inspiration, the supporting drone, is always there. It's what my friend meant when she quipped that even a budget could be a poem. She did not mean that one had to ruthlessly integrate identities in order to make oneself intelligible to the outside world, but that in poetry there was a kind of harmonic listening that could occur anywhere, and in any way.

The Woman Who Made Aquaman a Star

Gwynne Watkins interviews comics legend Ramona Fradon, the artist who created one of Aquaman’s most iconic looks. Fradon worked in the 1950s and 1970s, and you get the feeling the tidbits she drops about observing the male-dominated profession are just the tip of an iceberg of tasty gossip.

Fradon has talent and guts and cuttingly quick wit — and a healthy skepticism of certain segments of her audience.

Fradon couldn't be nicer, but she has the canniness of a woman who survived the some of the nation's hardest decades — and the pressures of an all-male industry — by her own wits. I confess to her that I'm only a casual comics reader; my husband is the one with a passion for superhero stories. "Could you explain that to me?" she asks with a smile. "I just do not understand the grown men who are so into comics."

Man-eaters

An absolutely engrossing excerpt from Brian Phillips’ Impossible Owls about searching for tigers in India. As Phillips re-traces the route of a famous hunter’s most famous kill, the great cats emerge from the negative space, an absence forced into bloody presence by the encroachment of human habitat (and human poaching). What is natural and what is not? Does “conservation” apply to an animal that hunts us?

One day I had been shown a newly built wall. It separated, I was told, the reserve from one of the villages. If a tiger killed a cow or an ox outside the reserve, the villagers were entitled to compensation from the government. If it killed one inside the reserve, they were not. Villagers whose cattle were killed in the reserve had been caught dragging the carcass into their own yards in order to claim the payment, and so the government had built the wall, not to stop tigers from attacking the villagers or their cattle, but to stop the villagers from claiming payments they were not owed. Until 2006, it had been illegal for forest dwellers even to own the land they lived on; the law had been changed over furious objections from conservationists. I was beginning to perceive that not everyone living in this scenario might feel a strong passion for wildlife conservation. I was beginning to think that preserving nature for the next generation might seem a less academic notion in New York than on the threshold of the actual jungle — how under certain circumstances it might sound like a mystifying collection of words, and how it might in fact sound more mystifying the closer to "nature" one came.

Whatcha Reading, EJ Koh?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

EJ Koh is the author of A Lesser Love, winner of the Pleiades Editors Prize, and her memoir The Magical Language of Others forthcoming from Tin House. Her poems and translations have appeared in Boston Review, Columbia Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, PEN America, World Literature Today, and of course, here on the Seattle Review of Books. She has accepted fellowships from The American Literary Translators Association, Kundiman, and The MacDowell Colony.

What are you reading now?

A collection of fiction by Korean women The Future of Silence translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton. It’s one of very few collections of Korean writing in the English-speaking world. Stories like O Chong-hui’s “Wayfarer” and Park Wan-so’s “Identical Apartments” make noises in my heart, noises I've never heard. One of my favorites, So Young-un’s “Dear Distant Love,” with its repressed, reclaimed visuality and story is darkly moving.

What did you read last?

After Jhumpa Lahiri published her self-reflections in the Italian language, I picked up the English translation In Other Words. The possibility of a new language giving birth to a new voice is both familiar and startling. I ask myself these same questions: Could I write a story in the Korean language? Would I dare to write a poem in the Japanese language? How does this change my writing, the place from which I speak?

What are you reading next?

I will begin Crystal Hana Kim’s If You Leave Me. It’s a debut that tackles the birth of modern Korea, beginning at the refugee camps and through the aftermath of war. I’m looking forward to experiencing the characters, the intimate story, but especially the lessons.

September 2018's Post-it note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we’re posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson’s Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here’s her wrap-up and statement from September’s posts.

September's Theme: Recently

When I say these post-its are from my life “recently” I mean “about a month ago”. Giant wildfires ravaging the western half of this continent notwithstanding, a month ago looks like a gentler time, a less in-your-face-awful time than last week. Or perhaps last month’s worries have just receded in memory, obscured by the newest onslaught. In late August I was disregarding all the warnings, exercising in the lake each day despite air quality risks and my asthma. Normally healthy people were dropping like flies from the ash, getting sick, staying in, canceling plans. But it makes me so happy to swim outside, and bleak as it was out there, it also looked fascinating. If I have to be surrounded by grim foreboding environmental conditions, I suppose I might as well let myself revel in the weirdness of that bright orange greyness, whole days of what appears to be cold misty dawn but is also irrefutably 90-degree afternoon. As the fires settled down, a drab work meeting randomly rekindled my romance with Seattle Public Library. How had I lost track of how personally swoon-inducing the library is? For a month now I’ve literally felt it increase my happiness every single day. I’ve always liked any excuse for a walk, and honestly, just strolling down now and then to see what’s there or return something feels ridiculously pleasant. At 7:30pm, when I need a break from work — and they’re still open! And everything is free!! The world crushingly brutal and yet THE LIBRARY IS STILL THERE, AND IT JUST WANTS TO HELP. Still doing its job to help everybody out, no matter your finances — an established, expansive kindness wildly anachronistic in our current landscape. Two days later watching the documentary Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood, I felt my world rearranged by solid evidence of Katharine Hepburn’s real life queerness. My deep early affinity, the enduring-yet-ever-denied sense of her being one of ours. Constantly crushed by the popular reality, her “devotion” to that male costar, the straight experience inevitably winning out over my more vulnerable one. Suddenly here it was — not just my hopeful imagination but credible accounts from real people — her queerness, and even his as well. The thoroughness washed over me with surprising force, opened something I’d learned to accept as closed without question. And yet the dominant narrative keeps ignoring, disbelieving, actively hiding such histories. Why is it still not ok for gay people to see ourselves? A couple days after that, reconnecting with an old friend, just for a day maybe, monumental and tiny. I don’t know why some things go so unsaid.

The Help Desk: The itsy bitsy spider learned how to not be a jerk

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

You remind me of my Aunt Alice, who once told me that the only difference between men and women was obligation, sensibility, kindness, and everything else. (But then again, she hated women, had "will obey" in her vows, and lived a very orthodox life.)

There was this one thing, though: she was really, really, really into spiders. She used to make all my dresses, and on every label she made a little black spider on a thread. Every birthday card: spiders. She once knit me an afghan that had all radiating spider web patterns.

Given how much you write about spiders I thought maybe you could throw some light on Aunt Alice. Any insights?

Beth, Redmond

Dear Beth,

Thanks. Based on your description, I strongly believe your aunt and I could've had a fine time alone together in a dim room, not speaking. I think we both identify with spiders' solitary, independent nature – they are unconcerned with being either overlooked or hated, as most are too busy with snacking and butt play.

And I suspect that your aunt would have a harder time hating women in today's climate. Even if you ignore for a moment judge Brett Kavanaugh's alleged sexual misconduct and under-oath lies, congressional Republicans' staunch support of getting this man's shithooks planted on the Supreme Court prove they have dropped the charade that women are human beings and should be listened to and respected as such. Why even call us women – why not "man's best friend"? They treat us alternately like bitches and dogs.

The silver lining is that more people are taking notice. It's not just self-ascribed feminists beating the drum about women's basic rights any more (like the right not to be groped and harassed, the right to be listened to and believed). Did you know that some spiders are social? And that their personality can change depending on what other spiders they're socializing with? If spiders can change, I have hope that more people can, too.

Kisses,

Cienna

PS. I want that afghan.

P.P.S. This conversation reminds me of the life and writings of Pearl S. Buck, who was raised in China by missionaries but went against her church and spoke out against Christian missions later on in life. She was also an ardent advocate for women and minority rights. You should read The Good Earth – it won a Pulitzer (and she won a Nobel Prize in Literature) way back before "affirmative action" became a sly talking point to dismiss the accomplishments of women and minorities.

Portrait Gallery: Sierra Golden

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Saturday, October 6:

The Slow Art Book Release Party

Join Seattle poet (and Seattle Review of Books’s September Poet in Residence) Sierra Golden for the release of her very first poetry collection, The Slow Art. Golden’s book is a poetic account of her time in the commercial fishing industry. To celebrate her book’s debut, Golden will be joined by local poets Maya Jewell Zeller and Sierra Nelson. And a country rock band called Lo-Liner will perform in between the readings.

Artspace Hiawatha Lofts, 843 Hiawatha Pl S, Seattle, 206-709-7611, http://www.artspacehiawatha.com, 5 pm, free.

Kissing Books: Emotional nutrition and narrative sustenance

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

The difficulty with writing happy endings these days isn’t just that it takes more effort to imagine happiness. The challenge is that all of this feels so endless.

I write this at the height of the Kavanaugh nomination and its procedural chaos — but by the time you read it there will undoubtedly have been another crisis, another tipping point that has us shivering and shaking and shouting into our phones. Humans are a narrative species, and we use stories to make sense of what we see happening around us. Dr. Ford tearfully recalling the worst experience of her life — while dozens of white, old, thin-lipped men sat by unmoved — looked like the climactic setpiece from any courtroom procedural of the past thirty years, or the Dolores Umbridge/Ministry of Magic scenes from Harry Potter. Kavanaugh’s self-aggrieved tantrum was a high school thespian’s reenactment of Nicholson’s rage-induced breakdown in A Few Good Men. It is not that we reach for fiction because we are incapable of facing reality on its own terms: we look for these parallels because we desperately need to know what might happen next. So we can prepare for it.

But this administration gives us no respite and no resolution. Everything is nonsense; causes don’t recognize their effects. Kavanaugh was voted forward — or not? Pending an FBI investigation? — and it may have been something we helped make happen? Or not? Is Jeff Flake just three Ouija boards stacked in a trenchcoat, or has something meaningful been done to steer this travesty from its worst outcome? Meanwhile hundreds of immigrant children have yet to be returned to their anxious parents, Flint still doesn’t have clean water, gerrymandering and voter suppression are denying civil rights to millions, Puerto Rico still struggles to recover from last year’s hurricane, regulation rollbacks open parks to drilling and remove safety standards from the food chain, disability and medical bills bankrupt more people, police brutality against black Americans continues unchecked, the ACA is under open threat, the Mueller investigation is doing whatever it is the Mueller investigation is doing, the new federal budget slashes millions from Medicaid and Medicare, and so on and so on and so on. There are stories I’m forgetting or that I’ve missed. We can’t get a handle on everything because it’s too much, and we can’t disengage because so much of it is quite literally life or death stakes. It is a viral attack on the public consciousness, with intent to disarm and overwhelm.

The idea that a crisis could actually just be over feels like an old-fashioned luxury. They are using our capacity to care about one another as a weapon against us. It’s evil. I am so constantly furious about this it’s a wonder my hair has not turned into a tangle of hissing snakes.

Assailed by too many competing stories, we select narratives in self-defense. Women and survivors across my timelines are posting shots of Judith and Holofernes, Wonder Woman, Xena. We are going over the movies and media we watched in our youth — Sixteen Candles and Revenge of the Nerds have been name-checked time and again — to offer concrete, pre-understood examples of what we’ve experienced. We’re searching for better stories, for comfort: the number of posts I’ve seen asking for f/f romance recs has trebled, at least. I believe this is no small part of the momentum behind the new wave of romantic comedies we’re seeing across film and streaming services. People are looking for better answers at the same time as they’re looking for ways of feeling less hopeless, exhausted, and confused.

Romance novels bring moral clarity and resolution like it’s going out of style. Here are our heroes and heroines: they may not be the best people right now, but they’re going to get better. And then they’ll be rewarded. Their struggles will cease. We can and will argue all day about what kind of character can legitimately be set up as a hero or heroine (some authors just cannot resist a Nazi redemption arc, ugh) but we can’t argue about the skeleton underneath. At this point picking up a romance doesn’t feel escapist anymore — or else it’s escapist the way that it would be escapist to consume coleslaw or citrus on a long sea voyage to keep scurvy at bay. More than anything, romance novels make it safe and rewarding to care about the characters you meet. Emotional nutrition. Narrative sustenance. There is something we need to thrive, and the cultural environment is deliberately denying it: we have to look for it elsewhere. Even the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park found ways to get around the lysine contingency meant to keep them captive. (You can picture me as a Velociraptor sniffing at the door, tapping my talons thoughtfully as I stalk the shadowed aisles of an industrial kitchen.)

This month’s column brings you two queer romances, two feminist historical novellas, a Miami-set contemporary, and a creepy little masterpiece where a Victorian magician falls in love with a futuristic assassin of eldritch horrors. Pick your poison. Take your medicine. Rest a little, then get back up and show these fuckers how strong we really are.

Recent Romances:

A Treason of Truths by Ada Harper (Carina Press: science fiction f/f)

Sci-fi romance is one of the hardest genre blends to get right. It requires the emotional arc between the protagonists to be as fully fleshed-out as the speculative twists of the plot. But when it’s done well it feels more complete than either genre alone: richer than technofiction, and more transportive than real-world romance. I’ve seen it done well before, but I’ve rarely seen it done this well, and damn if I’m not a little awed. A Treason of Truths is the sequel to the complex and gripping A Conspiracy of Whispers, and unlike most romance series these should definitely be read in proper order. The first book sets up the players and politics of Harper’s futuristic post-Crisis world — while giving us a sizzling romance between an Imperial prince and a prickly assassin from the dystopia next door — and this second book comes along to revel in the consequences. The fun of high-tech espionage, shady moral politics, and one of the best takes I’ve seen on the Fated Mates trope make these books an experience that shouldn’t be missed.

Empires live and die on the trading of secrets, and the family-bloodline-focused, gilt-plated Quillian Empire’s greatest spy is Lyre (aka the Liar, if you’re nasty). But Lyre has unsuspected secrets of her own: one, that she’s a rogue runaway from the floating Cloud Vault, a city-sized hoard of pre-Crisis knowledge and self-appointed technocrats who mostly steer clear of earthbound politics; two, that she’s helplessly, painfully, and irrevocably in love with the empress she serves.

Empress Sabine lost an eye in a failed coup attempt supported by a rival government — um, spoilers for book one — but it doesn’t take two eyes to see a trap when the Cloud Vault unusually offers to host peace negotiations. What follows is a stunning series of threats, rescues, escapes, betrayals, and revelations aboard a shining, tarnished and utterly creepy floating ship-city. Nanobots poison the bloodstream and turn people’s own bodies against them, mechanical moths scan every pipeline and passage for runaways, and eerie nightsbane-wolf crosses lurk in the shadows of the city’s forgotten underworld. All this plus a brutal, angst-filled, heart-twisting romance between two stubborn, wary, complicated women who can deceive everyone but one another.

If there is a book three someday I will shout my delight to the heavens.

A declaration — of need, of more than a need, of feeling — no, that was never supposed to be in the cards, but Lyre was a professional. She could cut her heart out for the game. She’d done it before. Working in intelligence meant carrying your own homeland inside you, soil to absorb it all until you could bleed in private. She’d thought she could control the reaction.

Counterpoint by Anna Zabo (Carina Press: contemporary m/pan m):

The real fantasy in romance is someone who sees you, and wants you, and loves you as you are. This fantasy has double the power in queer romance, which because of our culture has to traffic in a certain amount of invisibility. KJ Charles and Cat Sebastian’s m/m historicals make clear the risk a hero takes even in expressing interest in another man. Making queer desire visible can be fatal. Mx Zabo’s contemporaries deal in other kinds of erasure, within modern queer culture as well as around it: mental illness, kink and queer stereotypes, asexuality, public versus private personas. They have a glorious way of bringing to life the delicate give and take of a good seduction. Everything is carefully, thoughtfully, beautifully done — and all the hotter because of that. Of course, it helps that this series’ brand of kink is the cerebral, generous, ropes-and-leather command-and-obey kind (my favorite!) rather than the sadistic dungeon-full-of-spikes-and-whips kind. Give me a caring top who can dominate in a daytime hipster café with nothing but a piece of lemon meringue on a fork, and I’m one happy camper.

Domino Grinder is the guitarist for Twisted Wishes, a rock band on the upswing after an eventful whirlwind tour (shown in Mx Zabo’s excellent Syncopation). He curates the tattooed, spike-collared, bad-boy image carefully to protect his other self: shy, bookish, and submissive Dominic Bradley, who likes to put on bow ties and sweater-vests and cruise for handsome intellectual types. Such a man is pansexual programmer Adrian Doran, who knows lovely, expressive, wide-eyed, tie-me-up-please Dominic is just the kind of man he could fall for, and hard. But Dom is profoundly hesitant to reveal his other existence as Domino: not only because it’s a closely-guarded secret he fears will be leaked to the media, and not only because he thinks dommy Adrian would have no interest in brash, cocky, surly Domino (wrong! the reader wails internally). Mostly because Dom doesn’t know whether Dominic or Domino is the real one, his authentic self. For his part Adrian is dealing with being undermined and having his work essentially stolen by a newer, bro-ier programmer, and is in really no place to navigate a lover keeping a very big, very hurtful secret. This is the story of two complicated men who want and need each other desperately, and who are painfully careful and anxious about taking each step forward. Watching all the internal and external threads unspool, knots together, and ultimately release is an absolute pleasure.

“I’m in way over my head.”

“Shh.”

Adrian’s brow furrowed.

“So am I.” Dom closed his eyes. Oh fucking hell. He was gonna fall in love with Adrian. After two damn dates. That wasn’t safe and it wasn’t fair at all.

Miss Brodie’s Academy for Exceptional Young Ladies by Theresa Romain and Shana Galen (self-published: two historical m/f novellas):

Second-chance romance is a tricksy thing at novella length. On the one hand it lets us skip all the problem parts of the relationship and get right to the reconciliation. On the other hand…it lets us skip all the problem parts of the relationship, which is often where a lot of the tension and drama and heart-twisting feelings are generated. This volume features a pair of novellas in the quintessential modern Regency style, where a strong woman has carved out a feminist space within an overtly patriarchal world. Both are connected to the worlds of each author’s existing series — but only one left me wanting to explore more.

Shana Galen’s “Counterfeit Scandal” is a spy story without any spying, whose plot shows us neither counterfeiting nor a scandal. Hero Caleb worked for the Foreign Office during the Napoleonic Wars, embedded in a high position with the French army. He wreaked so much havoc that there is still a price on his head, so he lives quietly in a boarding-house in London. Heroine Bridget learned she was pregnant (!), married someone else (!!), and ended up in debtor’s prison (!!!) after the Foreign Office told her Caleb had died abroad (!!!!). Now she teaches art and forgery at an exclusive and very unusual academy. The two reunite by happenstance as Bridget searches for their son, who is somewhere in one of London’s many orphanages. Unfortunately, it’s clear we are watching this couple most closely at the least eventful part of their lives. Both the earlier Napoleon-and-debtor’s-prison sections or the reunited family’s sailing voyage to Canada seem like they’d have been stronger story fodder. (Imagine being on a long sailing voyage with your ex who you thought was dead, and the young son who only barely remembers you. And you have to pretend to be a happy family!) It made me wonder if there were just things I’d missed as someone who hasn’t read the author’s other books: there was a ghostly sense of weights and meanings that I ought to have felt in certain scenes, like hearing an inside joke where you don’t understand the reference.

Perhaps the unreality if the second story wouldn’t have felt so jarring if the first story hadn’t been so inviting and grounded and vivid. Theresa Romain’s “The Way to a Gentleman’s Heart” features academy cook Marianne Redfern as a heroine, and we’re treated to a bevy of concrete, anchoring details about recipes, cooking prep, budgeting, grocery shopping, and staffing issues. The crisis of how to plan a banquet when you’re understaffed feels more urgent than any of the vague espionage of the second novella. Food is one of the most irresistible things in fiction; it always means something culturally or emotionally or politically, so this story feels full of hooks that snag the heart. At one point hero Jack Grahame scours London’s markets to bring Marianne fresh honeycomb, just like they used to share as country lovers in years past. I just about swooned myself into a puddle on the floor, and it’s a great example of using a shorter story to give new readers a view into an established world. I wanted to move in at once, and order dinner.

He’d always liked her eyes. In a face as calm as any cameo painting, her changeable eyes had betrayed her true feelings. If he read their green depths correctly now, he’d caught her by surprise, and she wanted to flay him alive.

Night and Day by Andie J Christopher (Lyrical Press: contemporary m/f):

After the uncommon stress of the past few weeks, who’d have thought I’d enjoy a romance so much when it steers hard into questions of workplace affairs, abusive parents, and domestic violence? But such is the magic of a talented author: I was entranced.

Letty Gonzalez is hurt, angry, and desperate for a job: her art-festival-running ex dumped her and fired her when it turned out he couldn’t use her to access the family fortune. He also told her she was too fat for him to love, which tied in horribly to her issues with her fat-shaming mom and supermodel sister. Max Delgado is a grumpy sculptor with a simmering temper always on the verge of boiling over. He’s closed himself off for fear of becoming too much like his abusive father, and he’s only really able to express himself by heating and bending metal into abstract shapes. He also has a meddlesome, delightfully frank matchmaking grandma who I loved to pieces: Grandma Lola has decided Letty and Max would suit perfectly, so she fakes an email from Max hiring Letty as an assistant.

Letty shows up on the day Max is expecting a model for a sitting, so first thing right off the bat he demands she remove her clothes. And we’re off!

So many things in this book are messy: anger, pain, lust, fear, dysfunctional families. Letty’s wary of getting involved with another one of her bosses. Max is wary of losing control and hurting a woman he cares about. But the chemistry is stupid hot — and very palpable in the text, so it feels like a real problem and not a plot excuse — so even when both characters are just balls of electric insecurities, you’re rooting for them to figure it out and get back into bed already. Letty deserves orgasms! Max is ready to provide! She desperately needs to take care of someone, and he very much needs caring for! And the sexy bits are some of the most glorious filth I’ve read in a while: juicy, bawdy, slippery good fun. At the same time, the book puts the consent-and-power-dynamics questions of workplace harassment front and center, which is to say: how do you trust this motherfucker not to turn into a motherfucker like the last one? Consent is negotiated, offered, and withdrawn; boundaries are crossed, rethought, and reestablished. At the end of the book, after so many huge feelings and fuck-ups, I felt cleansed, wrung out, and excited about where our couple ended up. This was my first Andie J Christopher, but I promise you it’s not going to be my last.

When she brought the cups into the living room, she caught the tail end of Lola saying something like, “I didn’t come all the way over to Coconut Grove to watch you fuck this up.”

This Month’s Time-Travelling, Eldritch Horror-Slaying Heroine With A Gun Fueled by Her Own Blood And Incandescent Rage

No Proper Lady by Isabel Cooper (Sourcebooks: historical paranormal m/f):

This book was once pitched to me as Terminator meets My Fair Lady, and if you’re not already leaping for the buy button I don’t even know what we’re doing here.

Listen, there are just times when the most relatable heroine around is a gritty, wounded, half-starved, relentless assassin who has given up everything to come back in time and kill history’s greatest villain. Joan, daughter of Arthur and Leia, is humankind’s last hope. She has been sent back from the year 2188, a time when amorphous tentacular demons have taken over the earth and humanity’s remnants cower underground in the hope of surviving just one more muddy, miserable, sunless day. The man who started this all is Alex Reynell, a Victorian-era magician who possessed a book that let him open the doors to the demon world, destroying Earth and nearly everyone on it.

Joan of course has come to kill him. But first she has to find him.

She lands on the estate of magician Simon Grenville, who offers her shelter after she saves his life. Simon happens to be a former friend of Reynell, at least until Reynell started studying some of the really icky dark magics, so as Simon comes to believe Joan’s outlandish tale the two try to come up with ways to get Joan near Alex. Reynell moves in the highest circles of society — so naturally Joan has to learn to blend in with the aristocrats, which is where the My Fair Lady bit comes in. Meanwhile Joan is having a hard time adjusting to a world where gender roles are rigid but there is a shocking abundance of food and air and sunlight; she also painfully mourns the loss of her family, since it will be impossible for her to return to the future. Assuming it even exists once she’s done her job, that she doesn’t just wink out of existence as the last scrap of paradox. This book is darkly hopeful. This book is eerie. This book is one of the best fantasy romances I’ve ever read, and I cannot recommend it highly enough this Halloween season.

“Women are people,” she said calmly and cheerfully. “People are bastards. And someone who’s caged — no matter how pretty the bars are — is going to get bored and restless and go for the only entertainment she can. Even if that’s catching men.”

Thursday Comics Hangover: The color of adventure

The comics industry is twisting itself up into a knot over the fact that kids aren't reading superhero comics. Even though young people are attending superhero movies in sick-making numbers, they're not buying into the comics that serve as the basis for those movies.

But I find it hard to get too exercised over this "crisis." Kids are reading comics, probably in greater numbers than they have in decades. They're just reading about different kinds of heroes. These heroes look more like the kids of today — diverse, confident, proudly imperfect — and they don't carry any of the odd baggage that has accrued around superhero stories for the last six decades.

Early in The Sand Warrior, Oona finds herself on a predestined mission to reignite ancient beacons spread across five war-torn planets. She teams up with a space athlete and a strange little outcast to save the galaxy.

Creator-wise, it's hard to tell exactly who did what in the 5 Worlds series. It's written by brothers Alexis and Mark Siegel, but three illustrators are credited for the art: Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Whoever actually drew the thing deserves a ton of praise: the art is cute without being cloying, and imaginative while still being thoroughly relatable.

But the real genius here is the coloring: using a palette of pastels and gentle earth tones, these books are dreamy and warm and unlike all the other fantasy books on the shelves. A giant sand creature near the end of the first book is framed against a dusky sunrise and a gloomy moon, adding to the reader's sense of wonder. Whoever is responsible for coloring this book is breaking new ground in adventure comics; the superhero publishers should be ripping them off as shamelessly as possible.

Occasionally, the 5 Worlds books grind to a halt to provide exposition that will move the story forward for the next 30 or 40 pages. These info dumps are a bit too thick for their own good. Ooona says to someone early in the first book, "But...but I thought the Sand Castle and the Flying Fortress hated each other!" He replies,

Plumb visited with Domani diplomats but he was secretly teaching me. I came to understand there is something rotten in the heart of the Fortress these days! Toki stands against lighting the beacons! I escaped to continue my training because I believe lighting them is the right thing to do.

That's a lot of telling. Showing this character's backstory probably would have added a lot of pages to the book — at about 250 pages each, these are not exactly slim — but they would have made the story feel a little more organic.

But kids love exposition as long as it leads somewhere good. Oona's quest is perfect for young readers: she travels from planet to planet, lighting the way for a kinder, more inclusive future. You can keep your superheroes; she's just the hero that we need right now.

The Nordic theory of surviving the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings

Last week was, for me, the most disheartening, dismal week in American politics since the day Donald Trump won the election in 2016. For many of my friends, it was the single worst week in recent memory. We can quibble over the rankings, but one thing is clear: it was a terrible week for me to read The Nordic Theory of Everything by Anu Partanen.

I resented reading Nordic over the last week; with its fuzzy description of politics and policy in the Nordic countries, Partanen's memoir/political encomium felt frivolous and beside the point. The president was mocking sexual assault survivors, for Christ's sake! Maybe in a Hillary Clinton presidency, I could see myself reading Nordic and pining for a better way of life. But with the United States teetering ever-closer to a cross between the Cold War and the Civil War, Nordic felt like exactly the wrong book at exactly the wrong time.

I think most attendees of the Reading Through It Book Club last night at Third Place Books Seward Park happily didn't share in my resentment of Nordic. Some seemed to find great comfort in Partanen's book.

And I can totally understand why! It's a well-written book, and Partanen, a Finnish reporter who married an American, is in a unique position to write it. Her description of the various types of health care programs that exist around the world — from single-payer to federalized care — is the clearest and simplest explanation I've encountered in my life.

But I wish we had the luxury to sit around and wonder if our education system or our social safety net should be more like Sweden's. Children are being detained in camps at our border. Apocalyptic environmental predictions are being used to deregulate pollution. Worrying about parental leave seems pretty small in comparison.

Our conversation at the book club last night veered toward the cynical. We had a big discussion over whether one person's actions — particularly in an overwhelmingly liberal city like Seattle — can make a difference in the country. Every time we talked about the possibility of choosing a better system, an ugly truth would rear its head.

Ultimately, though, it's important to understand these other ways of doing things, these more humane ways to live. It's been said tens of thousands of times since the 2016 elections: Democrats can't win on a party-of-no platform. We have to supply an alternate narrative, a new understanding of what it means to be an American. And that means we can't go back to the incrementalism of the past. We have to embrace new ways of governing ourselves, and that means looking to good examples and learning what we can. Maybe Partanen's book is exactly the book we should all be reading right now.

Says Samantha Melamed at Philly.com:

Book deliveries to prisons across Pennsylvania were terminated this month as part of a multi-pronged security overhaul meant to eliminate avenues for drug smuggling. That meant an abrupt end to direct donations from programs like Books Through Bars, as well as orders shipped from Amazon or publishers.

But even though prisoners in Pennsylvania can't get books in the mail anymore, they can get access to "a library of 8,500 e-books that inmates, who make as little as 19 cents per hour, can purchase and read on $149 tablets provided by the vendor GTL." That's almost 800 hours of work to buy a tablet that gives them the ability to buy more books. This is totally immoral.

Today in gadgets that you don't really need

- If you're the kind of person who uses e-readers, you should know that yesterday, Kobo announced a new e-reader.

The new Kobo Forma sports an eight-inch display and weighs about 15 percent less than the Kobo Aura ONE. It might be a little lighter, but there are a lot of similarities between the Forma and Aura ONE. Like the Aura ONE, the Forma meets IPX8 standards — meaning it can be submerged for up to 60 minutes in up to six feet of water — uses the ComfortLight PRO system, which adjusts blue-light exposure throughout the day, and has a storage capacity of 8GB.

But really, you probably don't need an e-reader. I bought an e-reader from Sony years ago, and I barely used the thing after the initial thrill wore off. I've since read dozens of ebooks on my phone. People claim that phones are bad for e-reading because they have so many distractions on them, but in my experience, I've found that if the books are interesting enough they'll distract you from the distractions.

Speaking of distractions, some folks are crowdsourcing a laptop with an e-ink screen that doesn't have any other digital distractions. It's called The Traveler, and it's by the people who do the Freewrite digital typewriter.

Frankly, my favorite non-distraction digital reader is the Neo AlphaSmart 2, which is a battery-powered device that has absolutely no internet whatsoever. It's not being made anymore, so you have to buy it used.

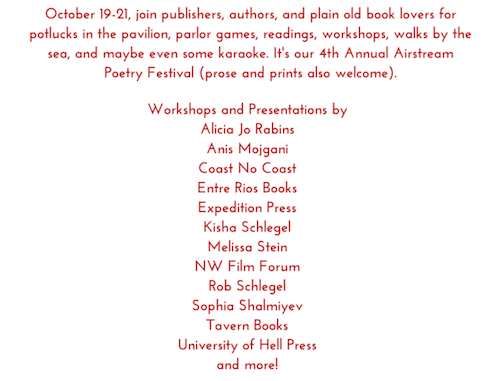

The Airstream Poetry Festival is the literary summit that Portland and Seattle always needed

At a time when festivals are getting slicker and more polished and market-tested to the point of homogeneity, the Airstream Poetry Festival is a delightfully catch-as-catch-can affair. Put together by Mother Foucault Books in Portland, the Airstream festival takes over the Sou’wester Lodge and Trailer Park in Seaview, Washington for a weekend of poetry readings, workshops, publishers, ocean walks, and karaoke.

The next Airstream Poetry Festival takes place the weekend of October 19th. Tickets are just $15, and they include a potluck dinner and omelette breakfast at the Airstream's outdoor kitchen. I talked on the phone with Heather Brown, the events organizer at Mother Foucault, about the four-year old festival. Brown says Airstream started as "a retreat for personnel and friends of the shop. It's been gradually becoming more official" in the intervening years, she says.

While originally the weekend just featured a single reading with poets like Matthew Dickman and Carl Adamshick and Ed Skoog, Airstream now blends readings with workshops, games, music, and film screenings (Northwest Film Forum will be in attendance this year with a collection of films curated by Seattle writer Chelsea Werner-Jatzke.)

Aside from the rural locale and laid-back vibe, the thing that makes Airstream especially interesting is the geography of it. The festival feels like a Portland-Seattle summit, since it's located roughly halfway between the two cities. "It's been really great to get interest on both sides toward meeting in the middle," Brown says. But Airstream casts an even wider net than that: Brown says Bay Area poets also take part in the festival, and that publishers Expedition Press and Copper Canyon are both heading down from Port Townsend.

While she's excited for all the events, Brown thinks Seattle Review of Books readers should especially take note of Alicia Jo Rabins, who'll be reading from her new book Fruit Geode. "She's also bringing music," Brown says, adding Rabins "composed a soundtrack for the book that she'll be pioneering at the festival." She's also interested in the typewriter-themed writing prompt that Expedition Press is overseeing.

Another fun thing about Airstream is that it intermingles workshops and readings in an interdisciplinary vibe. Smartly, it doesn't put up artificial walls between readers and writers of poetry and literature. "It's just a fun place to come," Brown says. "It's a great way to meet new people and also be encouraged in your craft, if you're a writer and to meet some writers up close if you're a reader and a fan."

"And also it's not totally writing-centric," Brown says. "It's very, multidisciplinary. We've got a lot of input from various creative streams." She adds, "and it's also just a great getaway."

Mail Call for October 2, 2018

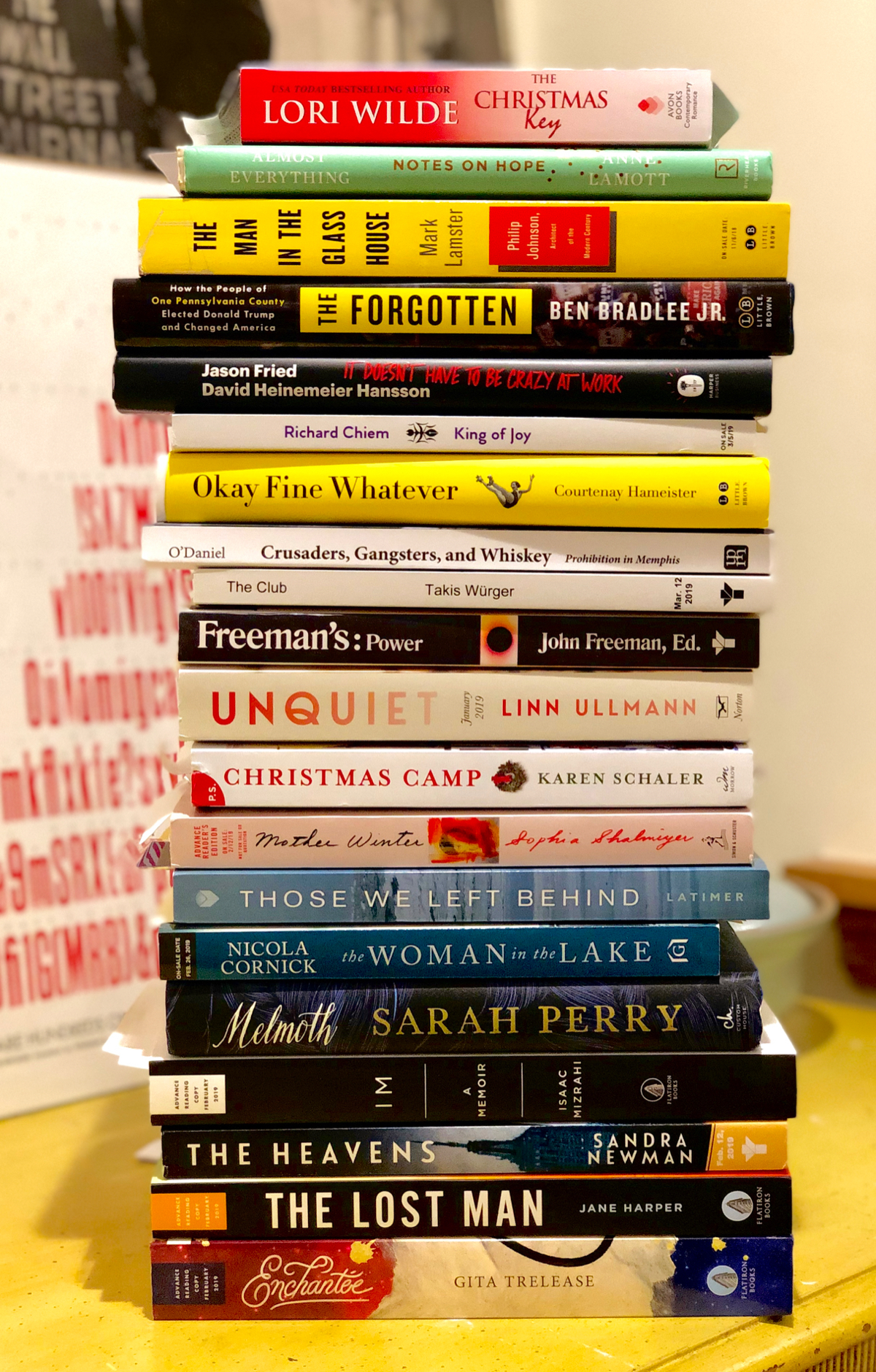

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Last week, while the country was reeling from the image of a credible, intelligent woman being forced to share the national attention with a pack of howling old white men, Alia Wong published a story in The Atlantic about gender and reading:

In two of the largest studies ever conducted into the reading habits of children in the United Kingdom, Keith Topping—a professor of educational and social research at Scotland’s University of Dundee—found that boys dedicate less time than girls to processing words, that they’re more prone to skipping passages or entire sections, and that they frequently choose books that are beneath their reading levels.

If we really want boys to have more empathy as they make their way in the world, we should encourage them to read more and to read better. That would be a good place to start.