Art & Life

Art saves nothing

and this is not art

just words running

in lines, hoping to reach

redemption. Meanwhile

time is running outfor bat and bee,

hippo and elephant.

Coral reefs are dying. Salmon,

once wild, breed in tubs.

Don't put your hope in poemsthat plot the putrid doings

of bankers, that bank

on Franz Marc's red horses

gamboling and grazing,

as if we'd never learned

to fabricate glue from hooves.

Congratulations to Sherman Alexie, who was nominated for his children's book Thunder Boy Jr. in the Young Readers' Literature category. We loved the book (as did our resident six-year-old).

And now seems like a good time to announce: join us, Sherman Alexie, Robert Lashley, and EJ Koh at the Elliott Bay Book Company on November 11th for a poetry reading. Eagle-eyed viewers will recognize this as our Bumbershoot lineup. We felt the night was so magical, we wanted to recreate it outside of the ticketed bounds of the Bumbershoot arena. Mark the date — we look forward to seeing you there.

Books! Books and rare books! And more!

This week's sponsor The Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair is back, for their twenty-ninth annual show at Seattle Center, happening October 8th-9th. The fair is an amazing event, a place to see rare books, ephemera, maps, and collectibles.

Find out more, and see a great video about the fair, on our sponsor's page.

It's thanks to sponsors like The Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair, and readers like you, that we're able to keep the pixels lit up here at the Seattle Review of Books. We've just released our next block of sponsorship opportunities. Check them out on the sponsorship page, and grab your date before they're gone.

Why does Carl Phillips need the Washington State Book Award?

The truth is, he doesn’t. In fact, Carl Phillips is confused about the controversy his nomination is causing among Washington state poets. When I spoke with Phillips this morning he mentioned his total surprise and delight when informed by his publisher that his book Renaissance was nominated for this year’s Washington State Book Award. He went on to say that the book was submitted by his publisher, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux. “It wouldn’t have occurred to me,” to send the book, he said, and followed up with how honored he felt. And why would Carl Phillips believe he was eligible? Phillips left the state a little less than a year after his birth and has returned exactly twice – once for the recent AWP in Seattle and once to board a cruise ship. He doesn’t think he will be able to attend the October 8th award ceremonies.

The real problem is not his nomination — Phillips is a lovely man and an extraordinarily gifted lyric poet, he deserves many awards. But for this year’s Washington State Book Award in Poetry, three out of the five finalists do not live in Washington State. They are residents of Missouri, Tennessee, and Utah.

Seattle Library’s website states a poetry book is eligible if the author:

was born in Washington state or is a current resident and has maintained residence here for at least three years.

So let’s unpack this. A poet could be born outside of Tacoma, leave before attending nursery school over 50 years ago, and become the winner of the Washington State Poetry Award. Perhaps she (or he) has never returned to Washington except for an AWP Conference. Another poet could have moved here in 2014, worked hard in the literary community, published a fabulous book, but she would not be eligible for this year’s award because she hasn’t lived in state for three years. How can we change these antiquated rules?

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Washington State Book Awards. Each year a select group of booksellers, librarians, and writers come together to decide on approximately five finalists in eight categories including Fiction, Poetry, Biography/Memoir, History/General Non-Fiction and four Children’s Books/YA categories. You can check their names on the Seattle Library website (scroll down to the very end). My point is not to vilify any hard working judge or any talented poet.

But is there any reason why a Washington state birth certificate trumps 30 months of actually living in this state? I’m genuinely confused. Perhaps the judges don’t think Washington State has enough skilled poets publishing books within our state lines? This is definitely not the case. Rick Barot’s, Chord, is the best book of poetry I have read in many years – it’s won several important national awards, but has not even been nominated for an award here where he has lived for more than a decade. Katharine Whitcomb’s, A Daughter’s Almanac, is a gorgeously experimental and important book, Whitcomb is a former Stegner Fellow and the co-editor of A Sense of Place: The Washington State Geospatial Poetry Anthology. Other poets with strong books that were passed over this year include Jenifer Lawrence, Jeannine Hall Gailey, Martha Silano, Michael Schmeltzer and Maya Zeller.

Poets in this town don’t like to cause a fuss. No one wants to seem unkind, or impolite. So when the list of finalists was announced last week, there were only a few quiet conversations with friends about why the Seattle Public Library Washington State Book Awards would decide to go outside the state for 3/5ths of the poetry finalists.

So after a lovely Washington road trip with another poet friend, I decided to broach the subject of this year’s award choices on social media. Here’s what I wrote on FB on Sunday:

Is anyone else concerned that WA State Book Awards in Poetry this year have more than half the nominations going to poets who do not live here and have not lived here in ages? I've no skin in the game (this year) other than this seems plain wrong. I was born and bred in Massachusetts. Until I was 38, the Boston area was home. But that doesn't make me eligible to send my poetry books to their prizes. And I agree that since I'm not living there — not for 18 years now — it would be odd to submit books written elsewhere.

Within a few hours over 45 people had responded — each of them agreeing that the rules of who is eligible for the Washington State Book Awards need to be changed. Kelli Agodon responded with this comment:

My concern is that the majority of the poets selected won't be at the award ceremony since they live out of state, while so many Washington poets who live in the state were neglected. I was shocked by the number of non-Washington poets & writers who were on this year's list. As a poet and cofounder of Two Sylvias Press, an independent Washington State book publisher, this troubles me. It is the "Washington State Book Award," and for me, this means that you live in the state currently.

So the problem isn’t with the three nonresidents or even with this year’s judges (only one of whom is a poet). The problem is with the rules. How can we get them changed?

For the last ten years or so, the library’s beloved Chris Higashi has organized the logistics of the judging. However, she has just stepped down and it is not clear yet who will take over her position. In the meantime, Carl Phillips is scheduled to read for Seattle Arts and Lectures this coming May. I hope to give him a tour of the area; it’s changed quite a bit since he left in 1960.

Counterfactual, counterhistory, counter memory

Published September 19, 2016, at 12:00pm

We love to build alternative Jewish homelands in literature. Ivan Schneider looks at the latest.

At Lion Heart Books, the shelves tell the story

Lion Heart Book Store houses an eclectic collection of volumes, keeping the shelves as interesting as their owner and visitors. The turnover is fast, too — titles come and go as everyone who visits finds something that intrigues them. The most popular books come from the fiction section, but people ask for a great variety of titles, editions, and genres. The mystery section is always well-stocked, with paperbacks stuffed into narrow shelves with no wiggle room. On the opposite wall of the store, by the entryway, is a scarce-but-growing children’s section. David is making the effort to start a Spanish section among the kids’ books, which further highlights his passion for people, for diversity and culture, and for being a part of something bigger.

Inside the shop there is almost certainly something for everyone. And if you don’t know what you want, talk to David for a few seconds and he’ll lead you to a book. There are racks of pocket poetry, assorted cards and artsy postcards, and trendy picks like adult coloring books. Bestsellers and classics stand on a small central table — copies of The Boys in the Boat, Pride and Prejudice, and Cannery Row. Vonnegut, clearly a favorite, lines the counter and displays, making the space even more lively with the vibrant and colorful book covers. Two tall glass cases stand at the end of the bookshelves, which are slim in size but not in pickings. These cases, containing fragile old books and small figurines, are a nod to David’s previous books and antiques store in Lake City.

While some of the books come from customers, David orders most of them, always careful to curate the selection to please visitors. I once visited as he was unpacking new arrivals, sorting through stacks of boxes in the small space behind the counter. With his amazing energy he unpacks, recommends, and entertains as he moves around his store. What results from his consideration is a perfectly varied selection that caters to every need. There are John Green novels, books about Seattle and Pike Place Market for souvenirs, quick reads for a plane ride, and obscure unheard-of titles. If you’re searching for the next item on your to-read list or don’t know what to gift someone, a visit to Lion Heart Book Store will not disappoint.

Sunday Post for September 18, 2016

Edward Albee, Playwright of a Desperate Generation, Dies at 88

One of the great tragedies of a good obituary is that someone needs to die in order for it to be read. I've seen a number of Albee plays, but knew very little about the man himself.

Sent to an adoption nursery in Manhattan before he was three weeks old, baby Edward was placed with Reed Albee, an heir to the Keith-Albee chain of vaudeville theaters, and his wife, Frances, who lived in Larchmont, N.Y. The couple had no children and formally adopted Edward 10 months later, naming him Edward Franklin Albee III after two of his adoptive father’s ancestors.

Patrician and distant, the Albees were unsuited to dealing with a child of artistic temperament, and in later years Mr. Albee would often recall an un-nourishing childhood in which he felt like an interloper in their home. In a 2011 interview at the Arena Stage in Washington with the director Molly Smith, he said that his mother had thrown out his first play — he described it as “a three-act sex farce” — which he wrote at age 14.

Pity the Substitute Teacher

Nicolson Baker has written a book about education, after going undercover and working in a school district as a substitute teacher. This is the part of the book review site where we link to another book review.

At 700-plus pages, Substitute: Going to School With a Thousand Kids is a surprisingly hefty contribution to the life-of-a-teacher genre, especially given that Baker clocked only 28 days in the classroom—a place he’d love to liberate kids from. (He enjoyed a 1970s school-without-walls progressive education himself. ) Scattered across three months and six schools, grades K–12, each of those days is chronicled with the moment-by-moment vividness that Baker has made one of his trademarks. In his novel The Mezzanine, for example, he plumbs an office worker’s thoughts during an escalator ride; fireplace rituals receive punctilious attention in A Box of Matches. Well before his teaching stint has ended, Baker the substitute has shifted into saboteur mode—the reporter as mischief-maker.

My father was an abusive sociopath, and i was the only one he had left

A hard personal story about obligation and family.

The last time I saw my father alive I was 22 years old and working at the Metropolitan Opera. I wasn't making much money but that is a relative statement, given that I had an apartment in Manhattan instead of a double-wide in mid-Michigan, like most of my childhood friends. It was the first time I truly believed I was not just getting out but staying out of the poverty that haunted our family tree.

The phone call came on a Tuesday while I was at work. This was long before I learned not to answer calls from numbers I didn't recognize. It was a hospital. My father had fallen and broken his back, and since he lived alone, no one had found him for 24 hours. He was still alive, somehow, when a cleaning lady discovered him at the bottom of the stairs and called 911. The hospital social worker found my phone number in his wallet. It was the only number of any kind that he had on him.

The Myth of the “Race Card”

Talking about race in America means talking about race in America:

Two essential quotes come up often among the black women in my professional cohort. The first is one that we attribute to Zora Neale Hurston: “If you are silent about your pain, they will kill you and say you enjoyed it.” The other is from Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals: “Your silence will not protect you.” We trade these quotes to nudge one another toward self-advocacy in situations when speaking up for ourselves might be difficult—such as in work or social settings where we are in a minority as women of color and our experiences of sexism or racism may be minimized or disbelieved, if we are vocal about them.

8 Faces: Collected - Kickstarter Fund Project #37

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

8 Faces: Collected. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

We’re re-designing and re-editing all 8 issues of typography magazine 8 Faces — and adding new content — to make a huge, hardback book.

What caught your eye?

8 Faces was an absolutely beautiful typography magazine. It wasn't cheap, but it was luxuriously printed and gorgeously designed.

Issues sold out quickly, and are impossible to find now. The creators are Kickstarting a new collected edition that takes all the content from all eight issues of the magazine, updates the layout, and puts them in one huge book. Score.

Why should I back it?

Because you love typography. Because you love reading articles and interviews about design, and a beautiful 500 page book about typography makes you feel a little funny in your stomach, like you're in love. Because you're missing an issue (or eight) from your collection. Because you want to support indie creators doing cool projects offline, that you can hold in your hands, and that will live in your library for the rest of your life.

How's the project doing?

30% funded with 28 days to go. Good trajectory, but let's see if we can help them out and spread the world. Every bit helps.

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 37

- Funds pledged: $740

- Funds collected: $600

- Unsuccessful pledges: 2

- Fund balance: $300

Help make Seattle's literary scene more diverse and inclusionary

In case you couldn't tell from our diversity reports or our thoughts on the current discussion on cultural appropriation in fiction, we take issues of diversity seriously here at the Seattle Review of Books. We don't always get it right, but we try. And we think it's always important for Seattle's literary community to keep issues of diversity in mind.

That's why I want you to know about the second in a series of free workshops on racial equity in the literary arts that's sponsored by Seattle: City of Literature. This workshop will be on "Implicit Bias," it takes place on September 27th, and you can RSVP for it right here.

In the workshop, Dr. Caprice Hollins will "will encourage participants to challenge the impact of racial sterotypes and implicit bias" in an effort to learn "how these unspoken and often unconscious stereotypes create barriers to genuine relationships and influence our attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs about one another." Hollins has over two decades of experience talking about these matters with organizations like Seattle Public Schools.

I interviewed City of Literature's interim executive director, Stesha Brandon, about the series of workshops a few months back. You don't need to have attended the last workshop in order to attend this one.

Every few months in Seattle's literary scene, someone will make a dumb statement about race, or host a panel of white dudes, or thoughtlessly encroach on someone else's culture. And every time this happens, the person in the spotlight will claim cluelessness. "I didn't realize," they'll say. "I should've known better." It's through conversations like this that we do realize, that we do learn how to do better. If you're part of an organization that deals with the literary arts in Seattle, I urge you to send someone to this workshop to listen and to report back what they've learned. This is how you avoid thoughtless mistakes; I'm so grateful to City of Literature for leading the way with these talks.

Beans and Rice and Tahini

When I was young I worked at a vegetarian restaurant, The Morningtown, which ironically, opened on the day I was born. Ironic, because working there was kind of a birth of my adult self from my teenage self. I learned a lot.

Every day for lunch a nice young woman would come in and order black beans and rice and tahini. We made really good tahini. She never varied her order, but she was a valued regular who ate there every day.

One day, I said to her: “you’re a great customer. Any menu item on the house today, to thank you for your business.”

The thought in the kitchen was that, maybe, she had a tight budget so always stuck to the cheapest item on the menu. Maybe she’d want burritos, or stir-fry, or pizza, all of which we had for a few more dollars (the food was so good there. Seriously.)

Maybe she could take half for dinner, we thought. Maybe she could order a big plate and take it away.

She said “Thank you. I’ll have the black beans and rice and tahini, please.”

“Okay,” I said. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” she said. Then she paused for moment, kind of looked at the ground, then me, and said:

“My life is very uncertain. I like that there is one thing I can count on every day when I’m surrounded by total chaos.”

This woman has been on my mind a lot this election cycle. I’m feeling her. Right now I just want to eat beans and rice and tahini every day.

Cienna Madrid is out sick this week. (Feel better, Cienna!) She'll be back next Friday. In the meantime, please enjoy a whole year's worth of Help Desk archives, and send Cienna get-well-soon e-cards and literary etiquette issues at advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

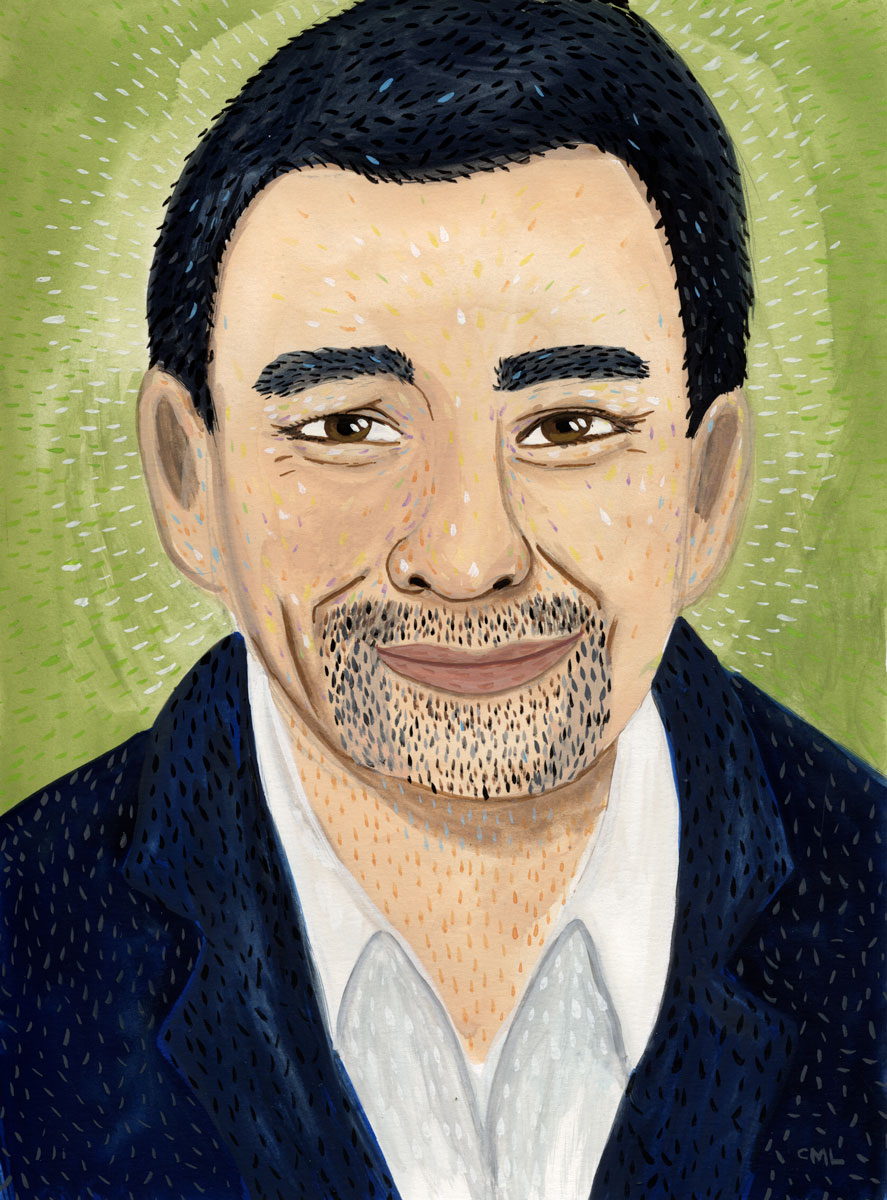

Portrait Gallery: Peter Ho Davies

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Novelist Peter Ho Davies appears tonight at Elliott Bay Book Company.

Book News Roundup: Open Books reopens this Saturday!

Wallingford's poetry-only bookstore Open Books is reopening for business under new management on Saturday at 11 am! There will be treats and a new art wall featuring visual work by poet Gabrielle Bates. You can like the event on Facebook and also follow Open Books on their brand new Twitter account.

Yesterday, the shortlist for the Washington State Book Awards was announced. Nominees include Shann Ray, Sharma Shields, Laura Da', Ann Pancake, Sonya Lea, Erik Larsen, and Martha Brockenbrough. Find the whole list at the Seattle Public Library's website.

Get ready for an insufferable press tour! The most criminally negligent president of our lifetimes is putting out an art book in February of next year:

The Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, announced today that it will publish a new book by George W. Bush, the 43rd President of the United States. Titled PORTRAITS OF COURAGE: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors, the book features 66 full-color portraits and a four-panel mural personally painted by President Bush of service members and veterans who have served our nation with honor, and whom the President has come to know personally since leaving office.

Lena Dunham will represent independent bookstores on Small Business Saturday this fall.

A University of New Hampshire library employee passed away, leaving four million dollars to the school. Of that four million, more than half is going to a new career center for students. One million dollars is going toward a fancy new scoreboard for the fancy new stadium UNH is building. And the library...is getting a measly $100,000.

Today in foolhardy-but-admirable actions:

Man runs into burning home in Broadmoor for laptop with 2 completed novels @theadvocateno https://t.co/CQaRYrzwot pic.twitter.com/khIqc8Cr6F

— Matthew Hinton (@MattHintonPhoto) September 15, 2016

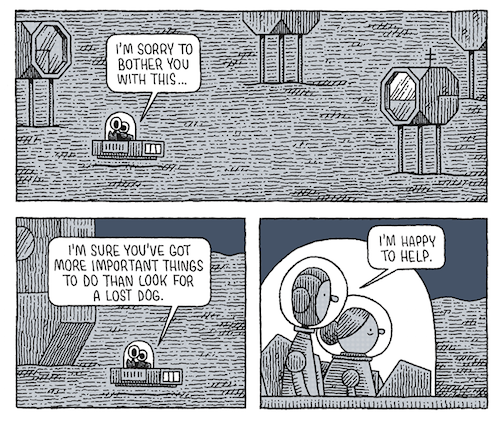

Thursday Comics Hangover: They put a man on the moon

If you love books and you haven’t read cartoonist Tom Gauld’s terrific collection You’re All Just Jealous of My Jetpack, you’re missing out. The book is packed with clever riffs on genre and famous authors, demonstrating Gauld’s deep reading life and obvious wit. He’s one of us, it announced to book nerds, and he’s not afraid to show it.

Gauld’s newest book, Mooncop, is totally different: it’s a single comics story, a(n admittedly slender) graphic novel that couldn’t be more rhythmically opposed to the compact gags of Jetpack. It’s the story of a police officer on the moon, years after a lunar colony’s glory days. Gauld takes his time with the story, eschewing the quick gags of Jetpack to draw many swaths of large silent panels to set the desolate scene. The humor in Mooncop is quieter, sadder, more humane.

And as a cartoonist, Gauld has never been stronger. The figures in Mooncop are still cartoony, with simplistic faces behind circular astronaut helmets and pipe-cleaner-bendy limbs. But the detail he packs into each panel is gorgeous: the empty landscape of the moon is made up of thousands of tiny wiggly lines, a sea of stone set against an indigo sky.

The title character in Mooncop, who for the sake of expediency I’ll just call Mooncop, is a hapless fellow, a lonely man who’s left to police the dwindling lunar population. Just about everyone else has moved back to earth. “Living on the moon,” an elderly woman muses to Mooncop, “Whatever were we thinking? It seems rather silly now.” Once the allure of the frontier has dissipated, it seems, the bulky helmets and space suits required to live on the moon aren’t worth all the trouble. But some people still fall for the romance of it all: Mooncop replies, “Not to me. I think what you did was wonderful.”

Mooncop rides around the lunar colony, helping people as best he can and cleaning up after the remains of the adventurous spirit that brought humanity to the moon. Even a museum tracking the history of space travel is moving back to earth because nobody on the moon cares anymore. Gauld does include a few great jokes, particularly involving a robot therapist that is woefully unequipped for its job, but they’re unhurried. He has the patience to allow them to show up when they’re good and ready.

It must be said that the last few pages of Mooncop seem telegraphed well in advance; anyone who’s read a melancholy comic or two will be able to predict where Gauld is going to end his story once the necessary elements are introduced to the narrative. But this isn’t a book that you read for a twist ending or a roller-coaster plot. It’s more of a character sketch, a tone poem.

Between Brexit and the rise of Trump, this is a very appropriate year for Mooncop. When faced with the future, whole populations are recoiling. That one small step for mankind seems to have been a step too far; we’d rather be down on earth, soaking in our familiar humid air, than experiencing new things or trying to embrace the future. It feels lonely out on the frontier these days.

On Lionel Shriver and cultural appropriation in fiction

In a keynote speech at the Brisbane Writers Festival, novelist Lionel Shriver said, “I am hopeful that the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’ is a passing fad.”

Shriver listed a number of instances in which students on college campuses were offended by acts they deemed to be cultural appropriation. You are probably familiar with at least some of these examples; they’ve been employed ad nauseam by pundits and Facebook posters who want to rail against “coddled millennials” or “PC culture run amok” or whatever it is they’re mad about today.

Suffice it to say: college students have always experimented with the idea of what it is to be an adult, and adults have always yelled at college students for being young. That adults are now yelling at college students for erring on the side of sensitivity says more about the failings of adults, to my mind, than it does about the failings of the students. If you’re arguing against an inclusive world, if you’re calling for less empathy in the universe, you’re wrong.

I have no doubt that some students have been so eager to create safe spaces that they inadvertently called for censorship. And censorship, even in the context of safety, is bad. But there is a difference between “demanding censorship” and “requesting that people be more considerate of others’ feelings,” and critics are too quick to confuse the latter for the former. And even when a student does go too far, using that student as an example of why a whole generation is bad and worthless does not contribute anything to the conversation.

Anyway, Shriver argues that the kids these days, with their sensitivity toward cultural appropriation, are hurting fiction. And then she finally gets to the ax that she wants to grind:

My most recent novel The Mandibles was taken to task by one reviewer for addressing an America that is “straight and white”. It happens that this is a multigenerational family saga – about a white family. I wasn’t instinctively inclined to insert a transvestite or bisexual, with issues that might distract from my central subject matter of apocalyptic economics.

While reading this essay, I was very confused about why Shriver was so upset until I got to the part about The Mandibles, and then it became clear to me: novelists will go a fair distance out of their way in order to pick a fight with a critic who they believe has wronged them.

Anyway, to hear Shriver say it, if she made a character in The Mandibles bisexual or a “transvestite,” that would “distract from my central subject matter.” In other words, anything that is not straight or white would be a distraction. So by Shriver’s math, if you want to publish a story about a serious issue, you’d better make your protagonists straight and white. Otherwise, those characters will taint the story with their otherness — their race, their sexuality — and distract you from making your point about economics or macramé, or whatever it is you really want to talk about.

This is an argument from a place of unexamined privilege: when you are categorized in society’s default position, every other position is an inconvenience, or a distraction, to you. Shriver warns that novelists might eventually become afraid to write about other perspectives:

Thus in the world of identity politics, fiction writers better be careful. If we do choose to import representatives of protected groups, special rules apply. If a character happens to be black, they have to be treated with kid gloves, and never be placed in scenes that, taken out of context, might seem disrespectful.

And she says the conclusion that writers should do a good job of representation is facile, and it’s asking too much of writers: “Efforts to persuasively enter the lives of others very different from us may fail: that’s a given. But maybe rather than having our heads taken off, we should get a few points for trying.”

The funny thing about this part of Shriver’s speech is that it very nearly rubs up against another common complaint against Kids These Days: the alleged “Everyone Gets a Trophy” culture that’s turning Kids These Days into Oversensitive PC Crybabies. Any novelist asking to be exempt from criticism should earn a raised eyebrow in response. Why wouldn’t a critic point out an author’s awkward approach to race, or gender?

The truth is, there are plenty of writers out there who write about people from cultures other than their own, and many of them do it well. In her comic Ms. Marvel, Seattle’s G. Willow Wilson, a white American woman, writes about a teenage Pakistani-American superhero, and that character has become a beloved icon in real-life Pakistani-American communities. This is because Wilson did due diligence: she talked with people who shared a background with her character. She engages them in conversations, she listens to them, and she reports back on what she hears in her stories.

Good fiction always has an element of journalism to it. Most good novels spring from an author’s curiosity. What’s it like to do that job? What was that historical figure like in real life? What would happen to the Earth if the moon exploded? What if an astronaut got stuck on Mars? Authors should always wonder what it’s like to be another person. And good authors do more than just imagine: they ask. They research. They talk. They learn. Novels are engines of empathy and to create them, writers have to be more empathetic than most.

So say you’ve done all the research you can do. Say you’ve talked to people who are unlike you, and you’ve done your best to represent them in your book. And say someone doesn’t like your book. Say they complain about it in a review. Or they ask you about it in a reading, or on Twitter. Say a few people agree with their complaint. What then?

Well, I guess then you’re a writer who wrote something that someone doesn’t like. That’s okay. There are plenty of those in the world. It happens. Other people get to not like your writing, and they even get to tell other people about it. It’s called freedom of speech. As a writer, you should celebrate it, not spend thousands of words whining about it at a keynote address in Brisbane. But then, I guess that’s your right, too, isn’t it?

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 14th - September 20th

Wednesday September 14th: Beacon Bards

Seattle poet Martha Silano’s splendid quarterly reading series is in transition: previously located out of a Beacon Hill coffee shop, it’s found a temporary home at Hugo House this month before moving to Third Place Books Seward Park. Tonight’s readers are David J.Daniels, Keeje Kuipers, Rachel Moritz, and Tiffany Midge. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday September 15th: The Fortunes Reading

Peter Ho Davies is one of the very finest novelists you haven’t heard of. His novel The Welsh Girl was longlisted for the Booker Prize, but his books have yet to break through the mainstream. That may change with The Fortunes, an ambitious history of America as told through a family of Chinese immigrants. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday September 16th: Play Anything Reading

Sure, you’ve heard the corporate buzzword “gamification” — the belief that if you turn any arduous task into a video game, people will clamor to do it. But game designer Ian Bogost has a different understanding of playfulness; he argues that limitations are what makes play so helpful, and by setting clear boundaries, we make life more rewarding. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Saturday September 17th: The Underground Railraod Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Sunday September 18th: Four Poets

Maged Zaher is, for real, one of Seattle’s best poets. His gorgeous love poems are funny, eerily true, and stridently political. Tonight he’s joined by three poets—Susan M. Schultz, who writes dense, proselike poetry; Norman Fischer, a Zen priest; and Stephen Collis, an environmental advocate from Vancouver—in a promising showcase. Gallery 1412, 1412 18th Ave, https://gallery1412dotorg.wordpress.com. $20. All ages. 7 p.m.

Monday September 19th: Commonwealth Reading

If you fell in love with Ann Patchett through her high-concept novel Bel Canto, you probably know what to expect from her newest novel, Commonwealth, about a pair of families whose courses are forever altered after a wayward kiss at a party: a compelling plot, gorgeous language, and pages that practically turn themselves. Benaroya Hall, 200 University St, 621-2230, http://lectures.org. $20-85. All ages. 7 p.m.Tuesday September 20th: Downfall Reading

Seattle’s J.A. Jance has been writing mysteries since the Big Bang. It’s easy to forget about a consistent record like that; with dozens of bestsellers to her name, Jance spoils her readers for choice. She reads tonight from the latest in her Joanna Brady series, and she’ll discuss her creative process and her four decades as a writer in Seattle. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Event of the Week: Colson Whitehead at Seattle Public Library on Saturday, September 17th

Remember when Oprah chose Jonathan Franzen’s novel The Corrections for her book club and Franzen publicly chafed at the designation? The poor dear seemed to regret the mainstream success that came with Oprah’s seal of approval; Franzen called the books that Oprah liked “schmaltzy,” and the kiss of Oprah’s commercial approval caused him to preen over his wounded literary pride for a decade.

You will never see Colson Whitehead shying away from Oprah’s love for his latest novel, The Underground Railroad. He embraced the giant “O” stickers on the front of his book with gratitude, and he’s been riding the wave of mainstream acceptance ever since. Why did the two novelists respond so differently to Oprah’s Book Club? Well, I think part of it comes down to basic manners: Franzen is by many accounts a brat, while Whitehead has never been anything but humble and forthcoming in his many Seattle-area appearances.

But there’s more to it than that. Whitehead is a fantastic novelist, one of the best in America today. (Certainly better than Franzen.) But he’s never been able to build up the audience that he deserves because every single one of his books is different from the others. Whitehead’s debut novel, The Intuitionist, imagined an alternate New York with dueling elevator inspector guilds. John Henry Days is a big, bold examination of the John Henry mythology. Apex Hides the Hurt is a dark, nasty satire of America’s embrace of shiny surfaces. Sag Harbor is a quiet, tender semiautobiographical novel about being an African-American kid in an affluent white vacation community. And Zone One is a zombie novel. As much as readers like to think of themselves as adventurous, folks get upset when an author’s new book bears no relation to the last. Franzen succeeds in part because he writes about unhappy white families again and again; Whitehead has had difficulty gaining readers because he never follows the same path twice.

Oprah is right: The Underground Railroad is Whitehead’s best book yet. It’s the story of a runaway slave named Cora in a world where the Underground Railroad is literally a train that runs underground. The America that Cora sees in her travels is at once very like our own and wildly divergent. While the terrors that Cora encounters may not exactly resemble the historic record, they capture the rotten spirit of slavery in chilling detail.

This is the rare critically acclaimed bestseller that deserves every ounce of its adoration, and more. The hype is real. You can believe Oprah, and its scores of other fans, including some guy who took The Underground Railroad on summer vacation and can’t stop talking about its “terrific…powerful” portraiture of race in America. That fan’s name is Barack Obama.

(Colson Whitehead reads at the Central branch of the Seattle Public Library downtown on Saturday, September 17th at 7 pm. The reading is free.)

Everfair, in love and war

Published September 13, 2016, at 1:01pm

In her first novel, Seattle author Nisi Shawl reimagines a colonial tragedy as a steampunk African kingdom.