Meet the matchmakers

You can have the best-stocked bookstore in the world, but without booksellers it would be nearly useless. In fact, a bookstore exists in that space where the booksellers and literature intersect. We need them to direct us to books — classics, rarities, backlist, brand-new bestsellers — and explain why we should be interested in them.

The new team of booksellers at Seward Park’s Third Place Books bring decades of bookselling experience to the neighborhood, along with a few new booksellers. And you can tell a lot about the bookstore by the books that this staff recommends. Without a single booksellers’ recommendation, how could you possibly recognize the thread that connects Joy Kogawa’s Obasan to Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age? And in a scene as overrun with novelty as comics, you need a bookseller to recommend Top Ten, Alan Moore and Gene Ha’s superhero/cop show pastiche, or else it would be lost in the gaudy flash of the graphic novel shelves.

Look at the books recommended by Third Place Books Seward Park’s Anje. There’s something here for everyone, from a trilogy of great genre page-turners — Beat the Reaper, The Martian, and Lock In — to more serious fare including Rebecca Solnit’s essential feminist manifesto Men Explain Things to Me to Nate Powell’s marvelous comics and the more cerebral sci-fi of Margaret Atwood and Ann Leckie, Anyone could find something to love in this eclectic shelf’s worth of books.

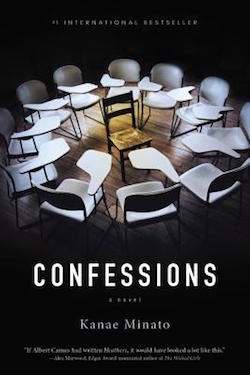

Or consider Wesley’s recommendation of Kanae Minato’s Confessions:

For better or worse, I am a self-declared book snob and rarely dabble in contemporary genre fiction. Finishing a Tana French or Gillian French novel has inspired little more than a drowsy "egh," but Confessions might be a watershed read. Its delightfully macabre plot, contemptible characters and artfully placed twists had me practically ripping out each page to get to the next.

The card worked on me, and I bought Confessions. Wesley is right; it’s a twisty, dark-spirited thriller, improbably narrated in the beginning by a woman out for revenge. It’s a morally compromised book, and one that might offend readers with its somewhat cavalier treatment of AIDS, but that weird ethical shakiness is part of its charm; you worry at every point that the book is going to turn into the literary equivalent of an exploitative snuff film, so you keep turning the pages to see what happens next.

And the thing is, I get books mailed to me every day of the damn week, and I’m in bookstores a lot, and I never would’ve found Confessions without Wesley’s recommendation card. No algorithm would’ve recommended it to me on a website. None of my friends would have pushed it into my hands, and no bestseller list would have alerted me to its existence. That serendipitous connection between reader and book never would’ve happened without the bookseller in the middle, to handle the introductions. That’s exactly what booksellers are for, and Third Place Books Seward Park has some phenomenal recommenders.

The Sunday Post for June 26, 2016

Road Tripping While Female

Road trips have been a fascination for decades. They are trips with endless possibilities, a chance to venture into the unfamiliar to find yourself. But as Bernadette Murphy points out, the presence of female road-trippers in literature is severely lacking. Jack Kerouacs fill the niche of road narratives, and always with exciting adventures. With women, however, the narratives focus more on the dangers of the road.

That film just turned 25, and the fact it remains as one of the only female-centered road trip narratives to have entered the lingua franca in the past quarter century implies that women either don’t have an interest in being on the road or, more tellingly, that they feel unsafe doing so. We know that women certainly face more life challenges, not having the same freedom as men if we have children and other home-based responsibilities. But the few stories of female road trips that do make it onto the larger cultural stage are more likely to be cautionary tales than celebrations of life and personal growth.

Which begs the question: Why is it that road trips, when undertaken by men in literature, seem to be about expanding one’s life and its context, about seeing the bigger world and how the man fits into it, and yet when undertaken by women, are most often in flight from dangerous situations, and seldom, if ever, for pure adventure?

The Psychology of Brexit

You've seen the economic analyses, the apocalypse memes, and the shocked tweets. But how do you explain Brexit from a psychological viewpoint? What were the voters thinking? Thomas Hills, Ph.D., teaches psychology at the University of Warwick and studies the decisions we make throughout our lives. He says, "Underlying the Brexit vote is a story as old as time."

Many have characterized the emotional divide as a split between the Angry and the Scared. The Angry wanted to throw the negotiating table at the EU, and they made claims that often ended with an implicit WTF. The Scared were worried about the consequences of leaving and provided evidence of a similar but different style. These often showed lines going up and down and through the top or bottom of charts. Everyone knows that lines should never rapidly approach the edge of a chart.

Sound check: the quietest place in the U.S.

In bustling cities, we often forget about the comfort of silence. Fortunately, Washington has the quietest square inch in the Lower 48 and it seems Seattleites appreciate it enough to fight for its protection. Samantha Larson hikes to this square inch and interviews Gordon Hempton, the acoustic ecologist that now champions the protection of these untouched environments.

But the quiet spaces — defined not by their lack of sound, which could include birdsong and wind rustling leaves, but their lack of manmade noise — are quickly disappearing. By some estimates, noise pollution affects more than 88 percent of the contiguous U.S.

According to Hempton, the slice of forest I visited has less noise pollution than any other spot in the American wilderness, which is why he chose it as the “One Square Inch of Silence” he wants to sonically protect, with a law that would prohibit air traffic overhead.

Invisibilia: Is Your Personality Fixed, Or Can You Change Who You Are?

An interesting excerpt from NPR's Invisibilia podcast. Alix Spiegel considers the story of a prisoner who claims he is a completely different person from the one that committed a ghastly crime. Our society loves the subject of personalities - we take BuzzFeed quizzes, read our horoscopes, and put our Myers-Briggs type in our Tinder bios. What if personalities aren't as stable as we thought, as psychologist Walter Mischel suggests?

Dan says it took him about two years to reconfigure his personality. He wanted to be less aggressive, less impulsive, more conscientious. He says he's now a different person. But he knows most people won't see him that way.

"I'm forever going to be a criminal," he says, "which I'm not. I've become a completely different human being at this point."

Delia Cohen had a hard time accepting that Dan had changed; you hear those words so often from people, and they're often not true. But she decided to suspend her disbelief and work with him on the TEDx project. They started exchanging emails.

A Permanent Home for Kurt Vonnegut’s Legacy - Kickstarter Fund Project #25

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

A Permanent Home for Kurt Vonnegut’s Legacy. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer

Who is the Creator?

Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library.

What do they have to say about the project?

Help preserve Kurt Vonnegut’s legacy by securing a new, permanent home for the Kurt Vonnegut Museum * Library in Indianapolis, IN.

What caught your eye?

We here at the SRoB are fans of Vonnegut. So was Julia A. Whitehead, but unlike us, she founded a library in the man's name: the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library in Indianapolis. Besides holding artifacts and memorabilia from the man himself, as well as exhibits, the Library does outreach into the community, holds events, and even runs an annual literary journal.

Now they're trying to move to a larger location in Indianapolis, and are raising money to secure the new location.

Why should I back it?

Maybe you're a Vonnegut fan, like us. Maybe you've got a connection to Indianapolis, or would just like to visit someday. Maybe you like the idea of memorial library like this that does outreach and acts as a cultural institution to carry on the works of a single writer.

If that describes you, now would be the time to get in.

How's the project doing?

They're 39% funded with 19 days to go. It'll be a long slog to $100,000. Every little bit will help!

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 25

- Funds pledged: $500

- Funds collected: $420

- Unsuccessful pledges: 0

- Fund balance: $540

Bookselling ain't easy

I worked in bookstores for a dozen years — at a chain store for four years and at an independent shop for eight — and I have to say this Publishers Weekly essay by Wendy Werris that went viral yesterday about her two weeks working at Barnes & Noble brings back a lot of bad memories. My bad memories aren’t of working at bookstores, mind you. They’re of people like Wendy Werris.

I probably worked with about a dozen variations on Wendy Werris, meaning roughly one every year. They might be a young man just out of grad school, or a woman on the edge of retirement, or some combination of those elements. These booksellers often go into the job with the idea that they’ll just talk about books and read all day. They usually have trouble working the computers, and they seem morally opposed to the idea of computers in bookstores at all. They generally last anywhere in the neighborhood of two to six weeks, and then they’re gone, leaving the staff shaking their heads in their wake.

The thing is, bookselling is work. Keeping on top of an inventory of thousands of items, each with its own unique product number, is work. Shelving and alphabetizing and receiving and returning books is work. Dealing with the public, as weird and wonderful as it can be, is a lot of emotional work. And no matter how many times you warn someone of that fact in an interview, sometimes they’ll be taken by surprise when they realize that it’s a job, with break times and lunch breaks and rushes and paperwork, just like any other job. The romanticized version they imagine—or, in Werris’s head, the idealized memory of a past bookstore job—quickly disappears. They never last long.

But I do want to highlight one thing about Werris’s essay that I believe is very important, and which more people should see. It’s this paragraph:

Every display and endcap in the store was formulized, clearly marked on the printed examples that arrived frequently from corporate. Everything was precisely copied; nothing was left to chance in the book, music, and gift departments. Booksellers didn’t have to think about merchandising—it was thought out for us, and all we had to do was match titles with the designated spaces on shelves and tables.

This is important, but not for the reason Werris mentions it. Those displays are all “formulized” because publishers pay Barnes & Noble for that display space, much in the same way that cereal manufacturers pay for placement on supermarket aisles. I believe a lot of browsers naively think that the displays in Barnes & Nobles are selected and placed by passionate staff members. That couldn’t be further from the truth. They’re paid advertising, plain and simple. This is not the case in most independent bookstores.

This doesn’t mean that you should not shop at Barnes & Noble. As I’ve said before, the publishing industry would be in terrible shape if Barnes & Noble went away. But it does mean that as a shopper, you should know when people are paying for shelf space. I would love to see a law that required retail businesses to place special signage on display space that was paid for by manufacturers. Maybe it would change your shopping habits, maybe it wouldn’t, but more transparency is never a bad thing.

The rest of Werris’s article, though, is bunk. I’d love to see a rebuttal written by someone who worked with her. That would be illuminating — and maybe more than a little cathartic.

The Help Desk: That new book smell

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Whenever people get angry about e-books, they always talk about how much they love the way books smell. Is this real? The only time I’ve ever smelled a book was when it was sitting in a musty basement for too long.

I’ve always had a decent sense of smell, I thought. I can tell when I forgot to put on deodorant in the morning, and I love new car smell. But of all the pleasures that books bring me, smell is not one of them.

Do books have a smell? What do they smell like?

Brian, Shoreline

Dear Brian,

What have you been doing with your life that you've only ever sniffed one book? I bet you've sniffed a handful of horrible things repeatedly in your life but you can't be bothered to pick up a book, close your eyes, and inhale until you run out of lung? I have three books sitting on my desk right now and each smells different: Shawn Vestal's Daredevils smells crisp, like socks fresh from the dryer; Sally Ride: America's First Woman in Space smells sour because I spilled old coffee on it; my 20-year-old copy of Flannery O'Connor's The Complete Stories smells like spiders in top hats because it is the book I return to the most often and thus have charged my most trusted spiders to watch over it like those somber circus-themed sentinels that guard the Vatican.

There have been scientific research papers written on how the smell of books change as they age. There are posters devoted to the aroma chemistry of them. Our memory is closely tied to our sense of smell, which is why book lovers cherish the scents that emanate from their favorite works, and which is probably why whenever I smell a spider in a top hat, I now have the urge to hug a wooden-legged woman.

If you're interested in seeing how books smell (har har), ask a handful of friends to bring over a favorite book and a bottle of wine. Cover the labels and blindfold yourself, and your friends can blindly drink and watch in amusement as you sniff out the unique notes of their favorite works.

Kisses,

Cienna

BONUS QUESTION:

Dear Cienna,

Enough about us. What have you been reading lately?

Donna, Winslow

Dear Donna,

My summer resolution is to put a dent in the Subaru-sized pile of books that have been gifted to me over the years. The last few books I've read include the above-mentioned Daredevils (for which I owe this fine website a book review), Sally Ride, Gilead, The Carter Family, and Between the World and Me. Currently I'm reading A Little Life, which is quite the depressing beach read! When I need a break, I reread an O'Connor short story because it's been long enough since my last time through The Complete Stories that her descriptions and humor awe and surprise me anew.

Thanks for asking!

Kisses,

Cienna

Well, er, good morning. Seattle writers are responding to the news that the world's gone all Trumpy. You should read Nicola Griffith on Brexit:

This vote broke the UK; it might break the EU. There will be a recession, a bad one. The xenophobes have been unleashed. This result has invited the whirlwind.

We're starting to see posts about what Brexit means for the publishing industry, but the truth is that nobody knows what's going to happen — not really. If you console yourself on difficult news days by watching very smart people try to think their way through events, Adam Rakunas has been very active on Twitter about all this, and G. Willow Wilson is always a worthy Twitter follow.

Some mornings you wake up and the world goes all screwy. The fact is, though, there are some things that are always true: You should vote. (You should always vote.) You should keep an open mind, and think before you speak. You should find the smartest, most compassionate people you know, and you should really listen to what they're saying. You should point out untruths when you see them and speak up for people who don't have a voice. And, of course, you've got to be kind.

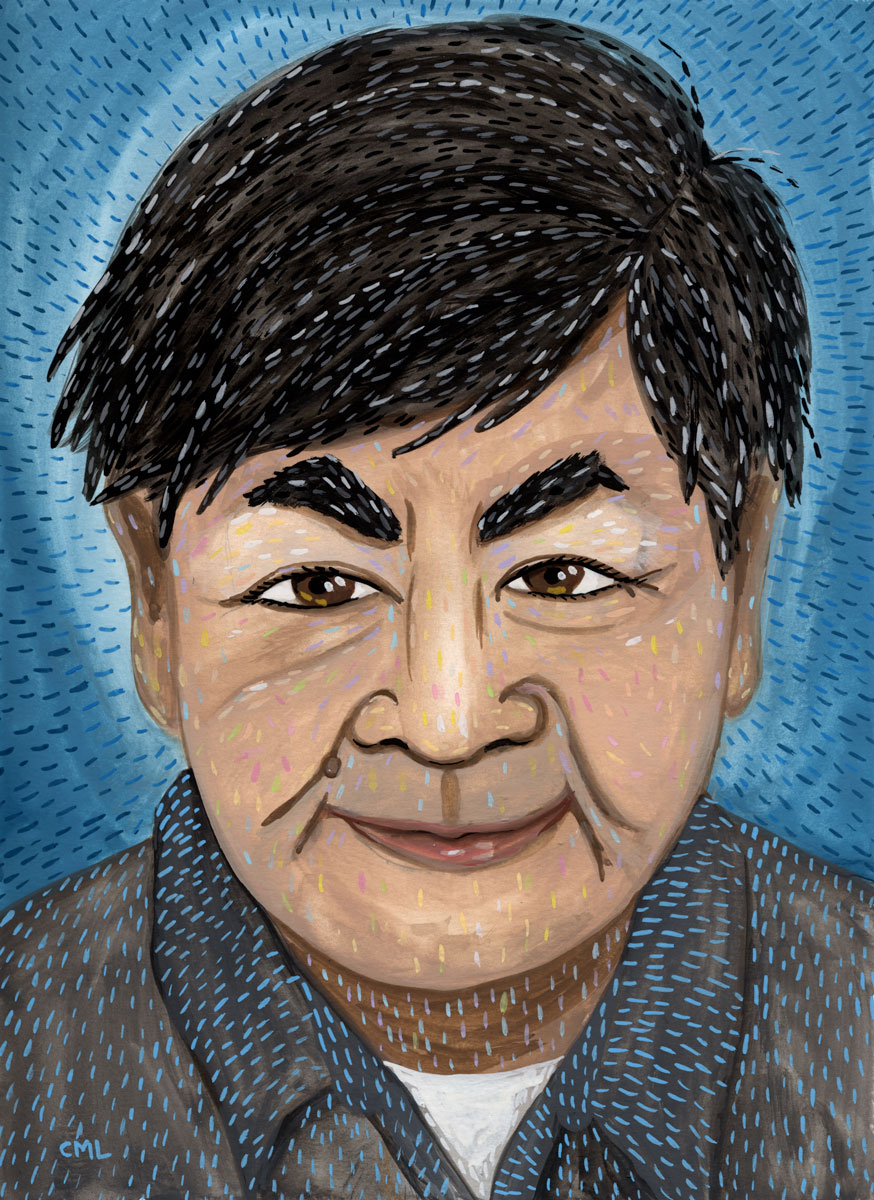

The Portrait Gallery - Koon Woon

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Koon Woon, influential Seattle poet and winner of the Pen Oak/Josephine Miles and American Book Awards, will be reading at Couth Buzzard Books tomorrow, Thursday, June 23. Stop by to hear about his experiences and his memoir, Paper-son Poet.

Travel far and read farther

Editor’s note: We’re thrilled to announce that the Seattle Review of Books has taken on our first intern! You’ll be seeing Rebecca around the site quite a bit over the course of the summer, and so we thought an introduction might be in order.

I’ve lived in the US, Belgium, France, and Mexico; road-tripped New Mexico, Utah, California, and the Northwest; jumped from coast to coast and back again — from Washington to Washington, now studying English and Psychology at American University in DC. I’m lucky enough to have seen a lot of this world. This instilled such a restlessness in me that the only way to satisfy it is through reading. Reading allows for even more extensive travel, for visiting places and times not accessible to me, for visiting the lives of people I’ll never meet.

I discovered the best way to travel through reading is via magical realism, a middle school find that still monopolizes my reading preferences. Gabriel García Márquez instigated this fascination — stronger today than ever before — when I read One Hundred Years of Solitude in seventh grade. It was a battered copy from my mom’s college bookstore, accompanied by various other García Márquez novels. The fantastic elements embedded in realistic stories add a certain depth and intrigue without making the story feel implausible, the way science fiction sometimes does. The reader vicariously experiences a whole other life and then some, an extra dimension not present in regular fiction. When something like insomnia becomes a contagious disease that spreads throughout a small town, the experience of reading about the plague feels real and wild and leaves the reader more well-travelled and exhausted. I love learning about things outside of what my imagination could create and reading conversations that will never take place. And magical realism, when implemented by the Van Goghs and da Vincis of literature, who so expertly paint with language, fills the spaces of my mind that yearn for that little extra something missing in regular fiction. So even if I’m old and arthritic, or too poor to visit new places, I’ll revel in the ability to know the hidden corners of the world and the hidden thoughts of strangers.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Outside the prison walls

It’s probably just a coincidence that the eighth issue of Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro’s sci-fi women-in-space-prison comic Bitch Planet was published less than a week after the fourth season of Orange Is the New Black arrived on Netflix. But, for the sake of people who write weekly columns about comic books, it’s a happy coincidence. From the very beginning, Bitch Planet has been compared with Orange, and it’s easy to see why: they’re both about womens’ prisons, they both feature diverse casts, and they’re both feminist-minded sociological studies of modern incarceration culture.

Anyway, the eighth issue of Bitch Planet is easily the best issue yet. The series has always been entertaining and confident — that first issue was easily one of the best series debuts of the last decade — but issue #8 hums with a special kind of power. It’s hitting that sweet collaborative spot where a writer and an artist sync together into a team that is greater than its parts.

De Landro is using more complex panel layouts in the service of more nuanced storytelling. An early scene in which a transgender woman (sentenced, an information box informs us, for “gender falsification, deceit”) undergoes a medical exam works as a microcosm of the series so far: in four pages we see dignity in the face of institutional demoralization, rebellion, pride, anger, and kindness. Another sequence in the middle of the book is heartbreaking and creepy, using a sci-fi backdrop to magnify a parents’ grief. It’s the most memorable image in an issue packed with memorable images.

(A quick aside: If you’re waiting to buy Bitch Planet in collected trade paperbacks, you’re missing out on something great: the back issue of every issue is packed with pages of interviews, columns, fan letters, and essays that expand on the themes of the issue. It’s like getting the modern version of a 90s riot grrrl zine for free with every issue of the comic.)

It’s hard to say where Bitch Planet will end up. This latest issue brings some political intrigue that suggests the story may be about to burst out of the confines of the prison. That would be just fine with me; Deconnick has made it abundantly clear in previous issues of this series that prisons aren’t the only way women are kept captive. Here’s hoping we’ll see a lot of breakouts before the series is through.

You are hopefully already watching #NoBillNoBreak, the Democratic Congressional sit-in to demand a vote on gun responsibility laws. It's a striking bit of political drama, and a battle over one of the most important issues of our time.

I just wanted to remind you that Georgia Congressman John Lewis, the originator of this sit-in, has been at this kind of thing for a very long time, and he is the author of an amazing autobiographical comics series called The March about the fight for civil rights. There are two volumes out right now — here's Volume One, and here's Volume Two. The third and final book in the series will be published this August. If you're looking for inspiration, if you're looking to learn how to win a political fight when seemingly every force in the world is lined up against you, you should read these books.

Book News Roundup: The writer at the bridge, a world without Barnes & Noble, and a hip-hop residency at EMP

- Last month, Elissa Washuta become one of the most-envied writers in the Seattle area when she became the Fremont Bridge's very first writer-in-residence. UW Today interviewed Washuta about how that's going:

I’ll be spending many summer afternoons in a small, beautiful office in the northwest tower of the Fremont Bridge. The office is mine alone this summer, and it looks out over the Lake Washington Ship Canal. I watch the bridge open and close while I write. I listen to cars, passersby, boats and the yells of coxswains when the rowers come by in the late afternoons. While I’m in the office, I work on research and writing for a project about the bridge — its history, its metaphorical meaning and my relationship with it.

- Alex Shephard at The New Republic has written a great piece about why everyone should hope that Barnes & Noble doesn't go away forever. Here's a taste, but it's much more nuanced than this, and you should read the whole thing:

In a world without Barnes & Noble, risk-averse publishers will double down on celebrity authors and surefire hits. Literary writers without proven sales records will have difficulty getting published, as will young, debut novelists. The most literary of novels will be shunted to smaller publishers. Some will probably never be published at all. And rigorous nonfiction books, which often require extensive research and travel, will have a tough time finding a publisher with the capital to fund such efforts.

- Do you know any young spoken word poets? You should encourage them to apply for a hip-hop artist residency sponsored by the EMP and some local rapper guy:

EMP Museum is proud to partner with Arts Corps and Grammy Award-winning duo Macklemore & Ryan Lewis to offer a three-week intensive Hip-Hop Artist Residency focusing on creative songwriting, performance techniques, and beat production.

The Hip-Hop Artist Residency seeks aspiring teen hip-hop artists who want to get paid to learn from and work alongside professional teaching artists and a virtual who’s who from Seattle’s vast hip-hop and creative arts community.

All participants will record an EP of original music at a professional studio, and put on a final performance inside of EMP Museum’s Sky Church.

- If you have an Amazon account, you might have just picked up some free e-book credits from that very long and very uncomfortable e-book lawsuit between Amazon and Apple. I have nothing to add to this, so I'll let our own Martin McClellan have the final word:

I just got $6.28 in my Amazon account “funded” by Apple because of the antitrust settlement. I’d rather have a competitive ebook market.

— Martin McClellan (@hellbox) June 21, 2016

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 22nd - June 28th

Wednesday June 22: Grace Reading

If you’re going to attend one reading by a debut novelist this year, skip the horse-chokingly thick tour-de-force by the white-boy wunderkind from Brooklyn and attend this one instead. Narrated by a ghost—“I am dead” is the first line—Natashia Deón’s riveting Grace tells the story of black women in America’s slave trade. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday June 23: Margin Shift/Paper-son Poet Readings

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Margin Shift: 1809 E John St. All ages. Free. 7 p.m. Paper-son Poet: Couth Buzzard Books, 8310 Greenwood Ave N., http://buonobuzzard.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday June 24: Mary-Louise Parker with Sherman Alexie

Celebrity bios are often disappointments. But in talking to booksellers who’ve read advance copies of Weeds star Mary-Louise Parker’s memoir Dear Mr. You, you’ll notice that a certain relief creeps into their faces. “No,” they’ll say, “it’s actually good! It’s well-written.” Tonight, Parker will be grilled onstage by Seattle’s own Sherman Alexie. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 8 p.m.Saturday June 25: Don’t Look Away Launch

Seattle cartoonist Seth Goodkind’s artwork has a remarkable stickiness to it; your eye can’t look away from those inky depths and finely wrought details. Tonight, he’s debuting four new minicomics including Don’t Look Away, which collects his handsome, haunting portraits of people of color killed by police officers.Push/Pull, 5484 Shilshole Ave., 789-1710, http://pushpullseattle.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Sunday June 26: Magic and Loss Reading

Virginia Heffernan calls the internet one of “mankind’s great masterpieces.” (Is she aware that YouTube comment sections exist? Unclear.) Her new book imagines the internet as a work of art, and it discusses how our online lives are shaping human thought. Is Heffernan the Marshall McLuhan of our time, or does Reddit render her argument invalid? Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Monday June 27: Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching Reading

Mychal Denzel Smith’s new book frankly discusses race in America. It opens with the murder of Trayvon Martin and touches on topics like Black Lives Matter and the challenge of black masculinity. If you think you don’t need to read it because you’ve already read Between the World and Me, you’re part of the problem Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Tuesday June 21: Fight Club 2 and The Clasp

Elliott Bay Book Company hosts two authors who couldn’t be more aesthetically opposed. At 4 pm, Chuck Palahniuk signs his Fight Club sequel comic, the inventively titled Fight Club 2. Then at 7 pm, Sloane Crosley reads from her smart, funny, and smartly funny novel The Clasp. You’re either a Crosley person or a Palahniuk person; which is it gonna be? Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 4 p.m. and 7 p.m.Literary Events of the Week: Koon Woon and Margin Shift

Sometimes all the good things happen in a single night. These are the nights where you want to throw yourself into a large sterile glass tube, flip a mad-scientist switch, and then send a clone or two staggering off into the night, just so you’re sure you don’t miss a thing. Thursday, June 23rd is one of those nights.

The poetry collective Margin Shift has for years been presenting some of the liveliest, most diverse readings in town. Every one of their events is, well, an event. But on the 23rd, they’re hosting an outdoor “Almost Solstice”-themed barbecue/reading that looks like it could be one of the more fun, laid-back poetry events of the year.

The lineup includes a mix of Seattle poets (Sarah Baker, Tracy Gregory,) Seattle poets who are moving to Buffalo, of all places, (Travis A Sharp,) and poets from the Midwest (Laura Burgher) and Colorado (Denise Jarrott.) They’re young and vivacious authors, reading outdoors on one of the longest days of the year. Throw in a little beer and barbecued meat and exposed skin and this is a reading that could get you laid.

Koon has lived through enough to pack a thousand memoirs. He has publicly struggled with mental illness and he has lived on the streets of Seattle. He has worked dozens of odd jobs, become a small-press publisher, and written books sporadically throughout his life. (He published his second book, Water Chasing Water, at age 64.) Koon is a foundational force in Seattle’s literary scene, and he has not received the mainstream recognition that he deserves. This memoir, and this reading, are hopefully the beginning of the end of obscurity for him.

“I entered the literary world through the back door, writing to channel my emotions instead of acting out in the streets,” Koon wrote for Poets & Writers magazine in 2013. “I wrote because I could assuage my mental illness by clarifying to myself my feelings and perceptions of reality.”

Press materials for this reading refer to Koon’s “consensual” relationship with reality, and that’s perhaps the best description of a poet that I can imagine: Woon’s work is visceral—he writes about flesh and blood and bone and work—but it is not quite realism. In fact, his writing always feels like it’s coming from a different plane, and that he’s visiting us here on this godforsaken mudball because he likes us and wants to spend time with us. But he doesn’t need to be here: he’s one of those rare talents whose presence feels like a gift: surprising, spontaneous, overwhelming.

Margin Shift: 1809 E John St. 7 p.m. All ages. Free. Paper-son Poet: Couth Buzzard Books, 8310 Greenwood Ave N., http://buonobuzzard.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Interviewing Maggie Smith, and the editors of Waxwing Magazine, about the poem "Good Bones" going viral

After looking into why poems go viral, Kelli Russell Agodon was not done. She wanted to talk to the people involved, too. Here's her interview with poet Maggie Smith, and Waxwing Magazine editors Justin Bigos, Erin Stalcup, and W. Todd Kaneko.

The Poet of “Good Bones,” Maggie Smith

Kelli Russell Agodon: Can you trace back to the first person(s) who shared it or when it took off for you? Can you figure out (besides Waxwing) where/how it began to spread?

Maggie Smith: It was shared a lot among poet friends here in the US, but then somehow it started taking off in the UK, and that’s when it really caught fire. I think it was a combination of Times writer Caitlin Moran and singer Charlotte Church retweeting it that really got it rolling, and Guardian cartoonist Stephen Collins shared it on Facebook, I believe. But I don’t have a clear sense of how those folks came across it in the first place. This whole thing is a mystery to me.

Did it spread more on Facebook or Twitter?

Is it being shared on any other platforms? It’s spreading on both, though I think the global response has been through Twitter. I think I gained 1000 followers in just a few hours. I had to put my iPhone away.

When you wrote the poem did you think, "this is one of my best poems?" Or did it just feel like a regular good poem to you that readers may like?

No, that’s one of the funniest things, for me: I wrote the poem and was happy with it — I mean, I think it communicated what I wanted to say, and I believe it was a “good” poem, whatever that means — but I didn’t think it was the best poem I’d ever written. Not at all. And I certainly could not have imagined so many people reading it and relating to it. I’ve received messages, tweets, emails, DMs, and texts from people all day — some of whom live in places I’ve never seen and whose first languages I can’t read or speak. It’s just incredible.

What has been the most surreal moment of this viral poem (celebs following you on twitter, translations, something else?!)

Maybe tweeting back and forth with Caitlin Moran; I’m a fan, so her kind words meant so much to me. Or learning that writers and translators I admire will translate the poem into French, Italian, and Spanish. What an honor! But really, the most surreal moment has been every moment. It’s been overwhelming to hear from pregnant women, new parents, people grieving, and people like me who are sad and confused about what’s happening around the world, and to be told that something I wrote meant something to them.

The Editors of Waxwing Magazine: Justin Bigos, Erin Stalcup, and W. Todd Kaneko

Kelli Russell Agodon When you chose that poem, did it stand out for you in any way besides being an outstanding poem? Did you have any ideaor inkling that this poem would be shared so generously? And has any of your other poems been shared so widely?

Editors: We came upon the poem as part of an unsolicited submission from Maggie. We were reading the slush pile and suddenly there were these stunning poems, each one generous and beautiful and crafted with such great care and precision. We especially love how the poem is so restrained and so careful until the end when it breaks and the only appropriate word is “shithole.” It’s a poem that makes us understand how a vulgar moment is effective and lovely. The poem breaks and we break along with it. We knew immediately that we wanted “Good Bones” in Waxwing, and are incredibly grateful that Maggie wrote it and trusted us to publish it. We had no idea that it would “go viral” like it has, but really — it’s such a timely, beautiful, painful poem, so how could it not? Before “Good Bones,” our most-read piece was the poem “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude”, the title poem of Ross Gay’s latest book, which went on to win the National Book Critics Circle Award. It’s also a poem that feels very much of our time and, in the best way, uplifting.

It’s interesting that this particular poem has gone viral so quickly after the mass shooting in Orlando last weekend, and that people have cited the shooting as a reason they appreciate the poem. “Good Bones” was written and accepted for publication months before the Orlando massacre. While we agree the shooting lends this poem extra poignancy, we also feel this is a poem that speaks for our time, our daily experiences with violence and hate and death, and also of our human resilience. As the writer Kyle Minor wrote on Maggie Smith’s Facebook wall, “this is a poem people will be passing around and posting on their doors in a hundred years and also today and tomorrow.”

The voice of “Good Bones,” is female, a mother. A parent worrying about children — that does speak to much of the pain felt during and post-Orlando. Interestingly, all three Co-Editors of Waxwing have very recently became parents. But — and we don’t think saying this takes anything away from the beauty and necessity of a poem like “Good Bones” — we also feel that the voices of queer people of color need to be broadcast if we are going to heal and grow after Orlando. There are poems being written in direct response to, out of the immediate grief of, Orlando. Those poems need to be read, too. One of those voices is Christopher Soto’s (a.k.a. Loma’s). And there are many, many more. We hope they go viral also.

How has this affected your literary magazine? I'm assuming there are a huge number of hits to her poem. Is there anything you want to share about how this viral poem has been a positive for your journal?

Our readership increased by 50% in three days. That’s huge. The poem has been read almost as many times as people have visited our homepage! And many people shared the poem online as a screen shot, so many more people have read it than have visited our magazine. Waxwing is not yet three years old, and so it feels great to get increased readership, of course. Our mission at Waxwing is to promote “the tremendous cultural diversity of contemporary American literature, alongside international voices in translation.” We’re immensely grateful that this beautiful poem was broadcast so widely, reaching tens of thousands of people just in the first three days after it was published, and we hope it will help us accomplish our mission by sending us readers and writers who didn’t yet know about us.

I'd love to hear your thoughts about online journals and their value, mission, etc. in the literary community and in the world. In the early days, I was a big supporter of online journals when a lot of people were saying print was better--for me this is a HUGE reason why we need to support our online literary journals because they can get poetry out to a larger audience. I'd love any of your thoughts on viral poetry, the online world and sharing of poetry, etc.

A lot of people didn’t believe online journals could have the impact of print. We love how tangible print literary magazines are, and we hope the good ones survive, but you’re so right that online magazines have a much broader reach. Waxwing has been read in 154 countries, out of the 196 (or so — people don’t agree on the number) countries on the globe. We wouldn’t mail our journal to all those places, likely — people wouldn’t know about us in all those places without us being online. We’re grateful that our dear friend, Jason Robinson, is a web designer, and he made us a beautiful journal that feels as close to reading on the page as anything we’ve seen — the writing is primary, at the forefront, but with the bonus of being able to include music and videos, and to learn about the author if you want to, but not have that distraction. We find the journal elegant, but it also feels almost homemade, like the best magazines we hold in our hands.

We think what has happened with Maggie Smith’s poem confirms what we’ve known all along about online journals. The potential for a large readership is only a few clicks away, and with that readership comes a greater ability for a story or poem or essay to affect people. That’s a lot of power and a lot of responsibility to curate good work. And we also think, when a poem goes viral like this, it’s great for the writer and the journal, as the poem becomes a doorway to more material from that writer or in that journal. But more importantly, we think that the viral poem becomes a doorway to our shared experiences living in this modern world, delivered in that way that only poems can deliver them. People will read this poem and then go out and read more poems, and the world takes a tiny step toward being a better place — that’s a good thing.

A poet explores when poems go viral

When was the last time you remember a poem going viral? This week, despite ongoing reports of “poetry being dead” for the last fifteen years, Maggie Smith’s poem “Good Bones” has been shared generously and thousands of times over on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr, as well as the story being picked up in the Guardian, Slate, The Daily Dot, and The Oregonian.

I decided to follow path backwards to figure out how this poem ended up being passed on throughout the world. Here’s what I found.

On June 15, Waxwing Magazine, an online literary journal, published its current issue, which included three of Maggie Smith’s poems. On June 16, a musician/writer, Shira (@Shhhiraaa) says she saw Smith’s poem shared on poet Tarfia Faizullah’s Facebook page, so Shira went to Waxwing Magazine, snapped a screenshot of “Good Bones” and shared it. Shira’s Twitter account has 1481 followers and many people retweeted the poem to their followers. Several hours later Shira’s original tweet found its way into writer Caitlin Moran’s (@caitlinmoran with 570,000 followers) and musician Charlotte Church’s (@charlottechurch with 471,000 followers) Twitter feeds and they both retweeted “Good Bones.” From that point on, the poem took on a life of its own, being shared across the internet on various platform (and as of this writing, the poem is still being shared).

It’s like that Faberge Shampoo commercial in the 80s (I told two friends and they told two friends, and so on and so on and so on…). Since that early tweet by Shira, Maggie Smith’s poem has been retweeted over 1400 times, not to mention shared and retweeted several thousand times by other individuals and shared liberally on Facebook. After all the sharing on that first day, the UK’s Guardian picked up the story, giving it an even larger audience.

A few things need to be in order for something to go viral: the first is content. Maggie Smith’s poem is outstanding. It’s from a mother’s point of view trying to “sell the world” to her children as a beautiful place. Anyone reading the news lately knows, the world does not feel like a beautiful place these days. It feels painful and violent, and here in this world are the parents with their children so innocent of what is going on.

But a good poem is not enough to be passed around — I have read many outstanding poems that never were shared. This brings in the second need for a poem to go viral — timing. Right now, many of us are at a loss of words for the recent tragic events in Orlando and the world. When someone steps up with the words we wish we had thought of ourselves, we share them. “Good Bones” is both accessible and powerful to people who read poetry and people who don’t. It has a smart title with strong juxtaposition which offers a little edge with bones and says what we are looking for in the world: good. The poem in all instances crosses that border which sometimes leaves non-poetry readers on the sidelines not understanding why a poem is praised. With “Good Bones” we are all onboard the “I get it!” train.

The last time I remember another poem going viral was immediately after the Paris bombings. It was Warsan Shire’s poem, “What They Did Yesterday Afternoon,” though it was not her entire poem, just these lines:

Later that night

I held an atlas in my lap

ran my fingers across the whole world

and whispered

where does it hurt?

It answered

everywhere

everywhere

everywhere

Again, tragic news story, viral words.

Poems do not usually go viral. For every one poem that goes viral, there are thousands and thousands that only reaches a few dozen readers. I have in my head, a short list of poems I remember seeing pop up on social media and a handful of poems that have been shared as generously as Maggie Smith’s poem.

After Ferguson and the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, Danez Smith’s “alternate names for black boys” (originally published by Poetry Magazine) was shared on social media and a few years before that Patricia Lockwood’s poem, “Rape Joke” was published in The Awl on July 25, 2013 and immediately went viral. While Lockwood’s poem wasn’t shared in response to a tragic or terrible news story, it spoke to millions of women who have experienced rape or sexual assault.

The first poem I remember being passed around fifteen years ago, was a stanza from W.H. Auden’s poem, “September 1, 1939”:

Defenseless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

Before there were social media outlets, that poem arrived in my email box from a friend (a non-reader of poetry even) after the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. It was probably the first time in the online world I saw people reaching for poetry during a time of strife, anxiety, and fear. It was a time when I saw the healing elements of poetry at work, seeing friends send out words to help mend our country and each other.

So what does all this say about poems that go viral? Do poems only just go viral after tragic events?

Sometimes, but not always. Sometimes humorous poems make their way through—for a few years, Billy Collin’s “The Lanyard” kept making its way into my inbox around Mother’s Day. More recently, I’ve learned Fatimah Asghar, “Pluto Shits On The Universe” (again, originally published in Poetry Magazine) entertained its way around the Facebook solar system (sometimes with the poetry slam video of Asghar reciting the poem).

But frequently, it does seem that poetry is something we turn to when we are in pain. Staring into our computer screens after a tragedy, we ask ourselves: What can I say? And poems answer.

We turn to poetry to heal us, to share what we’re feeling, to connect us with others and to something that feels larger than us. We turn to poetry when we’re frightened and unsure how the story is going to turn out. We turn to poetry because someone else has felt as lost, as hurt, or as confused as we feel. We turn to poetry to remind ourselves we are not alone, and when we see it—a poem with the words we were looking for—we nod our heads: Yes, I feel that way too.

Gimlet

Once upon a time a man took me to dinner, asked

if I’d been abused as a child, like that would explain it.

Sure. I keep a cabinet of curiosities —

but that was never one of them. See the dust?

Things we’re too old for slip off shelves,

line up to watch. In direct sunlight they’re small,

made of ash, disintegrating like abrupt love.

To recall a memory weakens it,

which means what exactly? Between what I want

and what I want to be, I get a little lost.

Blame the dinners where my glass fills again and again

before it’s ever emptied. Trauma and der Traum

aren’t etymologically related, which makes sense

but also not.

The eBook Reader blog wonders:

Kindle ereaders are one of the few reading devices on the planet that don’t support ePub format.

Kindles are the most popular dedicated readers and ePub is the most common ebook format, so what gives?

Why doesn’t Amazon add support for ePub ebooks to Kindles?

I guess this could be a rhetorical question, but the answer is ridiculously obvious: because Amazon doesn't want to open its system up or allow people to read e-books that they've bought in other places. If you're buying an Amazon e-reader, you're buying into Amazon's system. That deal is never, ever, ever going to change. If you expect Amazon to open their system up because it's the right thing to do, or because their customers would prefer to have one e-book library rather than a confusing mess of proprietary formats, you're going to be waiting for a very long time. It'll never happen.

Two hundred years ago this week

Sponsor Entre Rios books is back. Did you know it's been two hundred years, this week, since Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont, and Percy Bysshe Shelley met at Lake Geneva, and spun the stories that would turn into Dracula and Frankenstein?

But it wasn't only horror and science fiction that came that fateful time together. Byron inspired Shelley, and pushed him to reach greater heights with his poetry. One avenue, unknown for many years, was Shelley's political work, which Entre Rios has collected (in Shelley's preferred order) in a small handsome volume. See a sample on our sponsors page.

It's thanks to sponsors like Entre Rios, and readers like you, we sold out this season of our sponsorships. We couldn't be more thrilled. If you'd like to be notified when we release the next block, sign up for our low-volume sponsors' mailing list.