“I’ll put ‘still emerging’ on my gravestone”: an interview with Robert Glück

“By autobiography, we meant daydreams, nightdreams, the act of writing, the relationship to the reader, the meeting of flesh and culture; the self as collaboration, the self as disintegration, the gaps, inconsistencies, and distortions of the self; the enjambments of power, family, history, and language.”

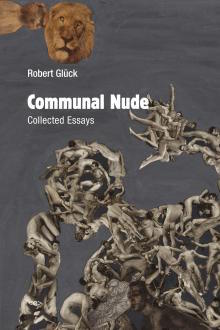

In Communal Nude: Collected Essays, this is one of the ways Robert Glück introduces New Narrative, a term he coined with Bruce Boone and Steve Abbott in the late 1970s to describe a form of prose writing emerging in the San Francisco Bay Area as a response to Language poetry and its formalist obsession with breaking apart (and breaking down) voice and context to interrogate the ways that words generate meaning. New Narrative writers included Glück, Boone, and Abbott, as well as Camille Roy, Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Mike Amnasan, Francesca Rosa, and Sam D’Allesandro—they admired the intellectual rigor of the Language poets, and the social worlds they created around their work, but wondered if this wasn’t just another straight-male dominated purity campaign.

New Narrative opened language up, but by addition rather than subtraction. New Narrative writers reveled in the excesses of voice—in sexual and romantic obsession, in gay and queer longing, in contradiction, gossip, pop culture, self-representation, shame, shamelessness, and all the possibilities and limitations of the body. Embracing the tangent, the non sequitur, and the nonlinear ramble, these writers refused to distinguish between fiction and autobiography, questioning texts in the process of creating them, and in the process creating other texts. Borrowing from the ideas of Marxism, New York School and Berkeley Renaissance poets, European critical theory, gay liberation, camp, and the dreams, schemes, and themes of their own relationships with one another, New Narrative writers rejected the conventional realism of mainstream fiction and the rigidity of the prevailing challenges to its reign.

New Narrative writing refused to separate the analytical from the personal, the societal from the intimate, the professional from the homemade, and Communal Nude is emblematic of these tenets. The book functions not just as an analysis of New Narrative, but as Glück’s informal autobiography through immersion in the work of others. The pieces in the book range from long-form essays to short rants, diary entries, introductory notes, lectures, art criticism, book reviews, and mini-biographies. It’s a historical scrapbook, and a literary collage.

“I am interested in writing that explores our pervasive sense of marginality, our loss of meaning and value, and the reconstruction of meaning and value,” Glück writes in Communal Nude, and here I talk to him about these lofty goals.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: You describe your writing practice as “theory-based,” but I think that, by centering the body and its needs, desires, and limitations, your writing is an antidote to the disembodiment of most theory. Is this part of your intention?

Robert Glück: The word theory conveys rigor, does it not? — so perhaps it’s misleading. Believe me, by the time I understand something, anyone can. I pillage theory — it interests me only when it gives me access to my own experience. Usually that does not mean whole systems of thought, often just a line or two. Except for Georges Bataille, who taught me so much. If you ever wonder what is the connection between death and sex, read Eroticism.

In a way, I think you’re making theory unnecessary by opening up the possibilities for embodied experience through writing—and, writing through embodied experience.

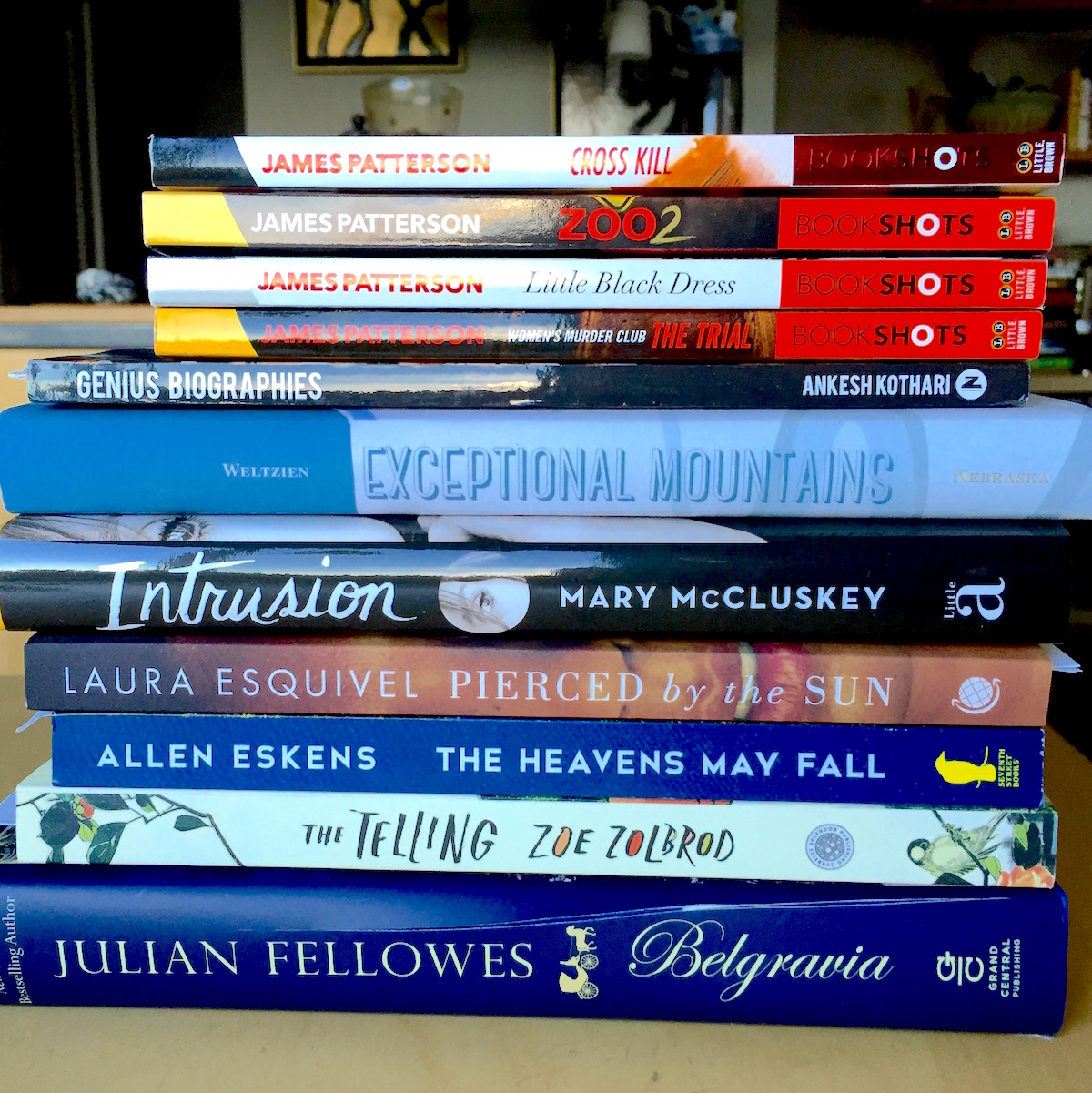

I guess my idea is to address the complexity of experience, not to make it add up. I gathered together the New Narrative essays in this book so they would all be in one place, but there are also essays on Kevin Costner’s Waterworld, the best lube to use, Georges Bataille, Kathy Acker, William Burroughs, essays on gardens, on certain artists, gay mid-life, Yoko Ono, O.J. Simpson….

You write, “The book becomes social practice that is lived.” In this way, you view writing as both an individual and collective process, a way to articulate and question the self, and a tool for community-building. What are the risks of this type of writing?

I wish I could put more risk into writing. I want a novel to be like performance art, where the audience and the performer share real time, where nakedness and disclosure are irreversible.

So when you say “the self is a collaborative project,” you’re challenging the narrow individualism of contemporary US politics.

Seeing the self as collaboration allows me to climb out of the box of psychology, where so much fiction is located. I can enter the intimacies of the body, so close the observations become general — it is thirst speaking, lust speaking. I can pull back into long shots that take in history, politics, the largest matter. I can do this and never abandon the precious fate of my dear characters, because I have added, not subtracted. We are either threadbare codes or larger, more porous, more glorious beings than most fiction wants to recognize.

You’re more interested in revealing contradictions than smoothing them out, and this strikes me as a loyalty to truth-telling not based on conventional middle-class norms. Is the dismantling of middle-class respectability part of your goal in writing?

I am happy if the sofa matches the drapes, but I don’t think literature should. I may set out to shock for the fun of it — why not? — but mostly I want to articulate as much of an experience as I can in as many different registers as possible, and that sometimes means saying more than is comfortable even to me. I want to say what is impossible to say because we don’t yet have a language to describe it.

In divulging your secrets, you invoke a sense of play in both writing and living, thinking and dreaming. Is there a tension between this ideal, and its practice?

I imagine there would be if I understood which was which. What is the ideal? Pouring a cup of tea for a friend? Having a job that is not alienated? Cooking a dinner with food that is nutritious and tasty?

It seems like one of your strategies in these essays is to resist closure, not just in the conventional sense, but even in terms of the very act of looking back at an essay to synthesize its meaning or impact. The final lines of the essays rarely force us to reassess the rest, and in this way they function more like conversations or monologues. Is this your intent?

Well, it’s probably just the way I think and move through the world. I am always reconsidering, re-deciding, remaking a plan. No decision is firm. No plan is final. It is sometimes very frustrating for my lover and for my publishers.

I love the prison journal you wrote after being arrested at an antinuclear protest in 1983, and held with 450 other male protesters in a tent at the Santa Rita jail for 10 days, while close to 800 female protesters were held in a nearby tent. While in general you point to desire as the formative impulse toward gay community, in this case it seems like you found a temporary community formed by the desire for change. Is there a contradiction between these two impulses?

What a good question! That essay is about negotiating my loneliness and longing in a tent with 450 men. I hope that desire for love and desire for change can go together. Certainly the best thinkers on the left wanted that. [Antonio] Gramsci felt that for a progressive movement to be viable, we should be able to find everything in it—culture, love, friendship. Not just a set of political goals, but also tuba bands. Could I substitute a bathhouse, or the broad smegmatic river that is Men Seeking Men on craigslist, for those tuba bands?

You say that, in the 1970s, gay community, “was not destroyed by commodity culture, which was destroying so many other communities; instead, it was founded in commodity culture.” Do you think that the intervening four decades of gay immersion in consumer culture have now destroyed genuine structures of community?

Yes. No.

Well, a community can be three strangers sharing an expression in an elevator. There is never not gay community. It may have migrated to the internet and social media, but what hasn’t? Or is it honeymooning in Niagara Falls? After bemoaning our preoccupation with society’s most oppressive institutions, marriage and the army, I did marry my Catalan partner, and this new civil right allows us to stay together in Sweden, where we live.

I’m sure you also agree that marriage shouldn’t be the only way to obtains rights that everyone should have access to.

I hope gay marriage will do exactly what its opponents fear — that is, change the institution. I can’t see why marriage should be limited to two people. Why not marry your dog, your toaster?

Toaster marriage would definitely function intrinsically as a critique, so I will toast to that. Some would argue that the assimilationist direction of gay politics became dominant in part due to social ostracism exacerbated by the AIDS crisis, and the drive by some gay men to appear “healthy” by conforming to straight norms. In a book that functions as an informal history, not just of your own life, but of gay culture, community-building, and creative practice over the last four decades or so, AIDS is a theme that only emerges occasionally. Was this intentional?

Nothing was intentional! It’s difficult to explain. AIDS shrank my writing horizon, Steve Abbott, Sam D’Allesandro, Bo Huston, editor George Stambolian, and a generation of queer readers as well [died due to AIDS-related causes]. Meanwhile I was doing anti-nuke work and anti-interventionist work with a gay affinity group. AIDS was personal. It meant driving my friend Ed to the hospital, watching movies with him in his bedroom, organizing a memorial, writing an obituary.

You’re now writing your “version of an AIDS memoir”—what does this look like?

The book is called About Ed. It takes me a long while to bring subject matter into fiction. Though what became the first section was originally published as “Everyman” in 1992. So you could say I have been thinking about AIDS steadily. I am glad it took me so long—now I am an old man playing with skulls. My own death was not part of the mix twenty-five years ago.

Ed Aulerich-Sugai was a Japanese-American artist and we were lovers during our twenties. Ed was a sexual mountain climber, a real explorer. Also he was a great dreamer—he could relate his dreams back through the night. The first section of About Ed is the day Ed was diagnosed. The second is his illness, his death, my mourning, and our life together in the seventies. The third is a fantasia of his dreams. I’m working on that now. I want the novel to be refracted through his dreams. I read twenty years of his dream journals to get him inside me. It was a very strange experience — for example, sometimes I would run into myself, always disappointing as it is for any eavesdropper. And do I really have Ed inside me? — or have his dreams given a shape to a feeling called Ed that was already there?

You write, “I take it as a given that the well-modulated distance of mainstream fiction is a system that contains and represses social conflict, and that one purpose of experimental work is to break open this system.” I agree wholeheartedly, but I wonder if experimental work often fails at this purpose by remaining willfully insular, a commodity for elite consumption. How can writers and other artists challenge this form of disengagement?

Like you, I write exactly what I want — not as simple as it sounds — and I put everything into it. Each new book is impossible — I am not fully engaged until I have made a book impossible to write. I’m not smart enough, I’m not skillful enough, not sufficiently empathetic—really I have to become a different person in order to write it, and I do. As for so-called difficult writing, well, usually writing is difficult not because there is a puzzle to unlock, but because the sense of time and representation is different from the reader’s expectations, yet it may be what we actually experience, and what we already accept in a painting or even a music video.

We experimentalists are so lucky — we are always emerging! We emerge till the day we die. I’ll put “Still Emerging” on my gravestone, if I have one.

A new bookseller, a longtime book lover

Last week, Third Place Books Seward Park manager Eric McDaniel said he liked having a mix of experienced booksellers and relative novices on staff. At least one of those new booksellers, though, isn’t new to the world of books: though Seward Park is the only bookstore where she’s worked, Naomi possesses an impressive resume including stints as a manager of the circulation desk at Yale libraries, and as a humanities professor. She holds a PhD in comparative literature.

“It’s great to be surrounded by books,” Naomi says when I ask how working at Seward Park has been. “It seems like a fairly easy move.” But she knows that there’s a difference between bookselling in a general interest bookstore and the world of academia. “I’m curious to see how my relationship to literature and books will change,” she says. “I think it will be fun to read more broadly.” Naomi’s interests are primarily “literature and philosophy and art. I read a fair amount of literary autobiographies and essays, but I definitely read a lot of fiction.” She’s especially interested in fiction in translation, which was one of her favorite subjects to teach.

Naomi’s recommendations are uniformly intelligent and passionate. In just a matter of minutes, she mentions Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, Walter Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood Around 1900, Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles, and, most especially, W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. She likes Sebald, she says “because he’s between genres. He didn’t call them novels, he said they were prose fictions, and they wander from subject to subject,” like a “fictionalized history, I guess.”

Visual art interests Naomi, and she especially likes how Sebald “incorporates photographs” into his work. She’s also deeply interested in the process of writing and of art, and how people’s different attitudes toward the creation of art affect the art itself.

It’s pretty obvious after just fifteen minutes of talking to Naomi that she’s an intellectual who is interested in intellectual pursuits. But it’s a highly inclusive appreciation of smart literature; she doesn’t make you feel dumb for not hearing about a classical author. She’s so enthusiastic about these books, and so eager to share her appreciation, that you’ll want to read the book just to understand and take part in that enthusiasm. In other words, she’s got this bookselling thing down.

The Sunday Post for June 18, 2016

What Would Happen If We Just Gave People Money?

A minimum guaranteed income is a hot topic right now, in advance of technological changes, like self-driving trucks, that are likely to put huge amounts of people out of work in very short order. That will be a huge hit on an already stretched-thin safety net. What if, instead, we just gave people money? That way, they can survive, they can get by, they can live a decent life, and have the resources to be trained in other work they will find more fulfilling. Andrew Flowers explores the concept in this article.

Werner posed a pair of simple questions to the crowd: What do you really want to do with your life? Are you doing what you really want to do? Whatever the answers, he suggested basic income was the means to achieve those goals. The idea is as simple as it is radical: Rather than concern itself with managing myriad social welfare and unemployment insurance programs, the government would instead regularly cut a no-strings-attached check to each citizen. No conditions. No questions. Everyone, rich or poor, employed or out of work would get the same amount of money. This arrangement would provide a path toward a new way of living: If people no longer had to worry about making ends meet, they could pursue the lives they want to live.

‘Could he actually win?’ Dave Eggers at a Donald Trump rally

Eggers is a good journalist — maybe he had preconceived notions of what he would find at a Trump rally, but he went, as an attendee instead of credentialed, to meet people and form an educated opinion of the people that are boosting the rise of the Donald.

I spent five hours at the Donald Trump rally in Sacramento, California, on 1 June. I spoke to and overheard dozens of the rally’s attendees, not as a journalist but as one ticketholder to another – I was dressed in jeans, workboots and wore a Nascar hat – and found every last one of the attendees to be genial, polite and, with a few notable exceptions, their opinions to be within the realm of reasonable. The rally was as peaceful and patriotic as a Fourth of July picnic.

And yet I came away with a host of new questions and concerns. Among them: why is it that the song Trump’s campaign uses to mark his arrival and departure is Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer?” Is it more troubling, or less troubling, knowing that no one in the audience really cares what he says? And could it be that because Trump’s supporters are not all drawn from the lunatic fringe, but in fact represent a broad cross-section of regular people, and far more women than would seem possible or rational, that he could actually win?

A rare, risky mission is underway to rescue sick scientists from the South Pole

An extraordinary tale of logistics and danger, from Sarah Kaplan.

Two small bush planes are flying to the South Pole this week to evacuate workers at the Amundsen-Scott research station — a feat rarely attempted during the middle of the Antarctic winter.

Kelly Falkner, the director of polar programs for the National Science Foundation (which runs the South Pole station), said that at least one seasonal employee for contractor Lockheed Martin requires medical treatment not available at the station and needs to be flown out. A second worker may also be rescued. Falkner couldn't provide further details about the medical motivation behind the rescues for privacy reasons.

Why It's Time to Repeal the Second Amendment

David S. Cohen in Rolling Stone calls for full repeal. He's not alone: the calls are rising after Orlando from people fed up with the ludicrous and absolutist rhetoric of the NRA. If you won't deal with common sense, then we'll start talking about the bigger deal: banning guns altogether. There's nothing in the Constitution that says we can't.

The Second Amendment needs to be repealed because it is outdated, a threat to liberty and a suicide pact. When the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, there were no weapons remotely like the AR-15 assault rifle and many of the advances of modern weaponry were long from being invented or popularized.

Sure, the Founders knew that the world evolved and that technology changed, but the weapons of today that are easily accessible are vastly different than anything that existed in 1791. When the Second Amendment was written, the Founders didn't have to weigh the risks of one man killing 49 and injuring 53 all by himself. Now we do, and the risk-benefit analysis of 1791 is flatly irrelevant to the risk-benefit analysis of today.

Good Bones

Maggie Smith's remarkable new poem went viral this week, as people processing grief and confusion and frustration over the shooting in Florida. It's a wonderful piece, and gives one hope about the future of poetry that such a finely wrought work can mean so much to so many people so soon.

Defensive Eating w/Morrissey & Comfort Eating w/Nick Cave - Kickstarter Fund Project #24

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Defensive Eating w/Morrissey & Comfort Eating w/Nick Cave. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer.

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

Illustrated vegan cookbooks to soothe your troubles by "goths eating things" artist Automne Zingg and traveling chef Joshua Ploeg.

What caught your eye?

I think it's pretty freaking self obvious, this time. First, they're cook books about vegan cuisine (which, I'm not, but go you vegans), and second they're about Morrissey and Nick Cave. Think about how many times those two musicians have fed your soul? Why not feed your body, too?

Plus, they're released by our friends at Microcosm Publishing in Portland, who put out a bunch of fantastic small-edition runs of weird, wonderful, and delightful books. They're one of those absolutely unique small American publishers that it's fun to support.

Why should I back it?

Because you're hungry. Because you're supporting an artist who took pain and made a humourous, serious expression. Who used the music that carried her through, and made this ode to the musicians that made it.

Because you want to support small artists, make some kick-ass vegan food, and do it while thinking about two great musical artists who inspired generations of people going through hard times.

How's the project doing?

Pretty good! They're just under 50% funded after a few days. No doubt they'll make it — get yours while you can!

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 24

- Funds pledged: $480

- Funds collected: $420

- Unsuccessful pledges: 0

- Fund balance: $560

The Help Desk: The grass is always green-eyed

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My brother married a gazillionaire heiress. She's really, really nice. She's generous, takes the whole family on luxury vacations where she pays for everything once a year, is crazy about my brother and they are, like, sickeningly cute together. And, she's beautiful, and smart, and has a big degree and a real career on top of it all.

Anyway. I can't help it but feel like trash around her. I dropped out of high school and had drug issues, and did stuff I'm not proud of. Now, I have my shit together like no other time in my life. I did it through writing, and sweating my pain and failure out of every pore in my body until my skin was clear. My life is really, really good now, and I'm working on my first novel, and I've been getting good feedback from my writer's group, and I have an agent that I'm talking to.

But goddammit, my sister-in-law just sold a novel. She did it to this big house with a star-studded agent, and I just know it's going to sell a gazillion copies. I mean, she's Ivy League, so she's smart and deserves it, but I just can't help but feel like it's so unfair. I feel like trash next to her, and she could stop working and give away her money every day of her life and still have enough to buy a country, but I have to struggle for every scrap. I don't begrudge her, but I can't help but feel jealous and awful, and I want to be a good sister to her too.

Help me, Cienna! What should I do?

Sister Heart, Capitol Hill

Dear Sister Heart,

Succumbing to jealousy is graceless and exhausting, like signing on to be the principal dancer in a clubfoot ballet.

I have been seethingly, sweatily jealous of two women as an adult: a fellow writer who I felt unfavorably compared to and the girlfriend of a man I briefly loved, who unfortunately shares many of my passions and hobbies (with the exception of breastfeeding spiders). Unlike you, there were no warring feelings of love for either woman. I felt only ugly things. At one point, I fantasized about the vainer one contracting jaw cancer and having her lower jaw removed so perhaps — just perhaps — she would post fewer pictures of herself doing things I loved to do (with the exception of breastfeeding spiders) with people I loved on the internet.

I wish I could say I overcame those feelings but I didn’t, not really. Fortunately, they burned so hot that they mostly burned themselves out. Once my all-consuming jealousy had collapsed into an emotional bruise that only ached when I acknowledged it, I was able to privately concede that neither woman deserved the emotions I ascribed to them. They had unwittingly threatened parts of my identity that I cherished, at times in my life when I felt especially vulnerable.

You, Sister Heart, are in an enviable position: You’re at a very good place in your life, you respect the woman you envy, and it sounds like you have a good relationship with her. You should know that her successes don’t undercut your own — the insights of a billionaire heiress writer are likely radically different from the insights of an ex-drug-using writer (and frankly, your life sounds more fascinating). There’s room in the publishing world for you both.

Looking back, if I were in your position and had a relationship with either woman, I would have exorcised my demons by telling them how I felt, in my own clubfooted way. Like, “I mostly enjoy your writing but I hate that people compare us because we’re both women.” Or: “I will probably always resent that a person who was so important to me treats you better than he ever could me. Sorry about that. Also, would it physically kill you to take a picture that didn’t prominently feature yourself in it?”

Sometimes I still fondly remember the jaw cancer.

Kisses,

Cienna

Lunch Date: Taking "Labor of Love" out for a cheesesteak

(Once in a while, I take a new book with me to lunch and give it a half an hour or so to grab my attention. Lunch Date is my judgment on that speed-dating experience.)

Who’s your date today? Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating, by Moira Weigel. Weigel will be reading at Elliott Bay Book Company tomorrow evening.

Where’d you go? Marination, the newest restaurant in the Marination Station empire, down on 6th and Virginia.

What’d you eat? I had the Korean Cheesesteak ("Kalbi beef with grilled onions and jalapenos, melted cheese, and mayo on a Macrina demi-baguette") and macaroni salad.

How was the food? It was very much in line with the other Marination restaurant's offerings, which is to say it's really good. The sandwich was excellent: cheesy and beefy without being sloppy or too heavy. Some of the cheese was fried to crispy shards on the outside of the sandwich, which was delightful. I love Marination Station's pork torta best of all, but this sandwich is right up there in terms of quality. The macaroni salad was suitably tangy, though I was a little disappointed to discover that there were no cubes of Spam in it, as it is in the macaroni salad at Marination Ma Kai.

What does your date say about itself? From the publisher’s promotional copy:

“Does anyone date anymore?” Today, the authorities tell us that courtship is in crisis. But when Moira Weigel dives into the history of sex and romance in modern America, she discovers that authorities have always said this. Ever since young men and women started to go out together, older generations have scolded them: That’s not the way to find true love. The first women who made dates with strangers were often arrested for prostitution; long before “hookup culture,” there were “petting parties”; before parents worried about cell phone apps, they fretted about joyrides and “parking.” Dating is always dying. But this does not mean that love is dead. It simply changes with the economy. Dating is, and always has been, tied to work.

Is there a representative quote? "The story of dating began when women left their homes and the homes of others where they had toiled as slaves and maids and moved to cities where they took jobs that let them mix with men."

Will you two end up in bed together? Oh, yes. The subject matter is engrossing, and Weigel blows up a few long-held misperceptions about dating in the first few pages. She also meanders delightfully, invoking the Real Housewives reality franchise, blue-footed boobies, and dating's seedy, unspoken "prostitution complex" in a dozen pages. She's a fine guide, and the book is lively and entertaining. It made for an excellent date.

After Seattle and San Diego, Portland gets the "honor" of hosting the third Amazon Books brick-and-mortar store.

“We are excited to be bringing Amazon Books to Washington Square, and we are currently hiring store managers and associates. Stay tuned for additional details down the road.”

Who's going to be the first person to showroom a book at Portland's Amazon Books and buy it from Powell's?

Portrait Gallery - Terry McMillan

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Terry McMillan, who our own Paul Constant called "a goddamned legend", is reading Monday at the main branch of the Seattle Public Library, in support of her new novel I Almost Forgot About You.

Book News Roundup: Octavia Butler predicts Donald Trump, bookstore sales climb almost 10 percent in April

Happy Bloomsday!

The Private Eye Writers of America have announced the nominees for their annual awards, the Shamuses. Local nominees include J.A. Jance and Ingrid Thoft, who were both nominated in the "Best Private Eye Novel" category.

Have you read the Neu Jorker, the spot-on New Yorker parody produced by comedy writers from The Onion, the Late Show with David Letterman, and more? It's eerie how good this magazine is, right down to the phony ads.

Did you know that Octavia Butler predicted Donald Trump and his slogan, "Make America Great Again," 16 years ago? Kashmir Hill writes at Fusion:

In the book, despite being down in the polls, Jarret is elected and his supporters feel empowered to declare martial law, enslaving people who are not Christian Americans. Jarret starts an ill-fated war with Canada, and is not ultimately re-elected.

Good news: Bookstore sales climbed almost 10 percent in April!

"And text itself will get weirder..." Tim Carmody at Kottke rebuts that Facebook-abandoning-text story from earlier this week.

The Humble Book Bundle is celebrating Pride month with a big e-book sale including the Gilbert Hernandez masterpiece Julio's Day, the experimental sci-fi comic The Infinite Loop, and an audio version of Sarah Waters's great Tipping the Velvet. Go get some LGBT literature for a low, low price.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Glaciers move faster than this comic book

In 2010 and early 2011, writer Brian Michael Bendis and his frequent collaborator, artist Alex Maleev, published the first five issues of a comic titled Scarlet. Bendis and Maleev have always been ideal collaborators: something about Bendis’s propensity for including too much Mamet-style dialogue on every page works well with Maleev’s photorealism, which often fails to convey action in any convincing way. Their comics — particularly their long run on Daredevil — tend to be wordy dramas that feel more like plays than the usual action movies you’ll find in superhero comics. They're better together than they are apart.

Scarlet is built on an intriguing premise. Set in Portland, the comic stars a woman named Scarlet Rue who targets the corrupt Portland Police Department in the hopes of starting a revolution. Scarlet frequently breaks the fourth wall to talk to the readers of the comic, and early in the series she promises to use the readers as a part of her plan, somehow. The book read like a cross between Fight Club, Occupy Wall Street, and a childrens’ TV show, and those first five issues were fairly vibrant examples of what Bendis could do when he focused his attention on expanding the medium in interesting ways.

Then nothing happened for two years.

In 2013, Maleev and Bendis published the next two issues of Scarlet.

Then nothing happened for three years.

Last month, Bendis and Maleev published the eighth issue of Scarlet, which was immediately followed by the ninth issue of Scarlet. Yesterday, they published the 10th issue. This wraps up the second story arc of the series, which will be collected soon as Scarlet, Book 2. This flurry of publishing came with the news that Scarlet was in development as a TV series for Cinemax. (Generously assuming one episode per published issue of the comic, it’s highly likely that the series will be very loosely based on the book, given that they’ll have to come up with their own stories in less than a single seasons’ worth of shows.)

The 10th issue of Scarlet kicks off with one of the best sequences in the book, a personal account of sexism within the Portland PD that opens up the interior life of a supporting character. The passage is illustrated in a sketchy, almost childlike, style unlike anything else Maleev has done, and it adds to the tremendous sense of stylistic potential that Scarlet has carried with it since the very beginning.

Unfortunately, the story then reverts to form, with Scarlet playing crowds of angry people against the Portland Police Department again — I’ve honestly lost count of how many times variations on this scene have played out, because I haven’t re-read the series in the six years it’s taken these ten issues to be published. And then on the last page of the issue come the words that will make all but the most cynical of readers throw up their hands in defeat: “TO BE CONTINUED…NEXT YEAR.”

Okay. It’s clear that Scarlet is not a money-maker of a series. (In addition to Scarlet, Bendis is also writing two Iron Man series — one of which is illustrated by Maleev — a Spider-Man series, a Guardian of the Galaxy series, and Marvel Comics’ big summer crossover event, Civil War II.) But this publishing schedule is ridiculous. There’s no point in publishing a story in individual issues like this if a reader could earn a graduate degree in the amount of time it takes for two full chapters to dribble out in ten comics. If the book is a labor of love for the two creators, why not just publish Scarlet in collected form? As it is, Maleev and Bendis are just frustrating the few loyal fans they have left with this erratic publication schedule and squandering the considerable good will they built with those striking first issues.

Tacocat lead singer (and former Stranger music editor) Emily Nokes, delightfully, reviews Korn guitarist Brian "Head" Welch's new memoir With My Eyes Wide Open: Miracles & Mistakes on My Way Back to KoRN over at The Talkhouse.

Rational Exuberance

Published June 15, 2016, at 12:01pm

Mary Roach's books are packed with poop and sex jokes, but they're really love letters to the obsessive nerds who make good science possible.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 15th - June 21st

Wednesday June 15: Grunt Reading

Perhaps you’ve read one or two of Mary Roach’s very funny investigations of weird everyday science (Stiff, about death and dying, was her debut; Bonk, about sex, was another high point). Her latest, Grunt, is about the science of war, and it promises more shocking, ridiculous, and downright disgusting revelations. I'll be joining Roach onstage for a Q&A. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Alternate Wednesday June 15: Words West

Because I'm involved with the Mary Roach reading and therefore biased, here's another event for your consideration. And it's a fine event, too: West Seattle’s finest reading series celebrates the conclusion of another stellar season with two excellent writers: Christopher Robinson is the co-author of a novel called War of the Encyclopaedists. He’s joined by Michael Schmeltzer, who wrote the Floating Bridge Press Chapbook Award-winning book Elegy/Elk River. C & P Coffee Company, 5612 California Ave SW. Free. All ages. 7 pmThursday June 16: Happy Family Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday June 17: Ultimate Bicycle Owner's Manual Reading

Self-described “Bike Snob” Eben Weiss has become one of the loudest and most-quoted bicycling advocates in the United States; if the Wall Street Journal needs a biking expert, he’s who they’ll call. So when he titles a book The Ultimate Bicycle Owner's Manual, he knows what the hell he’s talking about. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Saturday June 18: Labor of Love Reading

Moira Weigel’s book Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating is billed as a “history of sex and romance in America.” While she probably could’ve written five hundred tantalizing pages on forbidden pilgrim sex alone, the book aims to be a comprehensive survey, from petting parties to drive-in sex to OKCupid. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Sunday June 19: Staged Reading of Ulysses

You shouldn’t read James Joyce’s Ulysses on your own. You should come at Ulysses with study guides and David Lasky’s famous comic adaptation and this performance by Seattle’s own Wild Geese Players. Seeing and hearing the text come alive is one of the very best ways into one of the very best books in the English language Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 2 p.m.Monday June 20: I Almost Forgot About You Reading

Terry McMillan is a goddamned legend, a bestselling and hugely influential literary figure. Her books broke through the shelves of those embarrassing “African-American Literature” ghettos that Borders bookstores used to keep next to their fiction sections and delivered African-American literary voices to the mainstream. A new novel from her is always an event. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Tuesday June 21: All Those Vanished Engines Reading

Every summer, Seattle sci-fi writing workshop Clarion West brings big-name authors to town for a reading series. This year, they’re kicking it off with Paul Park, whose Princess of Roumania fantasy series was a huge critical and popular success. His latest, All Those Vanished Engines, combines Park’s own family history with a sci-fi alternate history of the U.S. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Literary Event of the Week: Happy Family with Maria Semple

“The pregnant girl enters the Trenton Family Clinic,” begins Tracy Barone’s debut novel Happy Family, “looking like she parted the Red Sea to get there. The lower half of her dress is wet with amniotic fluid, and the upper half is streaked with sweat.” This is a grand opening line for a novel, dense with imagery, evocative of the Bible, and thick with bodily fluids. It promises both legend and messy corporeality. It’s a woman’s body, split in two.

Happy Family is the story of Cheri Matzner, the baby who’s straining to be born in the book’s first sentence. Her mother, a teenager, runs away as soon as she gives birth, and Cheri is soon adopted by a couple with their own sketchy past. The book picks up with Cheri as an adult (seemingly of the high-functioning variety) as the secrets from her past boomerang back in the general direction of her head. On Thursday, June 16th, Barone will be reading from Happy Family at the Central Branch of the Seattle Public Library downtown. The most important element of this reading for Seattle audiences is that she’ll be joined onstage by Seattle author Maria Semple, who will be interviewing Barone about her novel.

It’s the appearance from Semple that elevates this from an intriguing appearance by a first-time out-of-town author into an absolute must-see. Semple, a writer for TV shows like Arrested Development who moved to Seattle and found international fame with her second novel, Where’d You Go, Bernadette, is an avid reader. If she loves a novel, she’ll recommend it to anyone within hollering distance. If she hates a book—and she hates a lot of books—it’s almost as though she’s morally offended. Her appearance at Barone’s reading is a sign of approval from a famously opinionated writer.

In addition, this is a rare public appearance for Semple; she’s been holed up for over a year writing her follow-up to Bernadette, a new novel titled Today Will Be Different which will be published this October. It’s possible that, since she’s been immersed in the new book for months, she might accidentally share some information about Different, which so far has been relatively shrouded in mystery, at this reading.

These two writers should have a lot to discuss. Barone could learn from Semple’s wild ride to international literary stardom. They could compare the way they use humor to soften the impact of some of the sharp-edged drama in their books. (Barone will use an off-kilter observation like a character’s propensity to talk dirty in Italian when aroused to mask a dysfunctional relationship, for instance, and Semple used Bernadette’s pathological loathing of all things Seattle to disguise her inner turmoil.) Wherever the conversation takes them, you’ll want to follow.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

This is a thank you post and a call to Instagram

We have an Instagram account! Let me utilize it here to extend some thanks.

Last Friday, Push/Pull Gallery and the Seattle Review of Books teamed up to host Christine Marie Larsen's opening at the Essential Natural Mattress store, in Belltown. Hanging on the wall, all around us, were the originals of the portraits she paints for us each week.

Also in attendence, were three readers who did us the honor of showing up, presenting some work, and then, posing with their portraits. Here they are in order of their reading:

Thanks to all three of our readers, to Christine for the wonderful portraits, to Maxx from Push/Pull for organizing event, and to you for showing up! The show will be hanging through July, if you missed it. It's really something to see those portraits all together — stop by and take a look, and grab a book from their little free library! 2008 1st Ave.

Labor of love

Published June 14, 2016, at 1:15pm

The second book in Adam Rakunas's Windswept series, Like a Boss,

Charlotte Runcie at The Telegraph does some literary sleuthing to contextualize the literary tradition that inspired the sonnet that Lin-Manuel Miranda read at the Tony Awards on Sunday.

...Miranda’s sonnet is 16 lines long, and has some moments of unconventional rhythm. What does that tell us? The best-known writer of the 16-line sonnet is probably the Victorian writer George Meredith, who wrote a sequence of them titled ‘Modern Love’, exploring his own disastrous marriage and expressing a sentiment that love in his time had become corrupted and corrosive.

Miranda adopts Meredith’s form and uses it to talk about his own good marriage, and about love as a positive and unbeatable force. To take a form that had been associated with a poet claiming love is rotten, only to turn it around to use it as a poem about the healing power of love in the face of darkness, is elegant, beautiful and extremely powerful.

(Thanks to SRoB tipper Paul for the link.)