Whatcha Reading, Deb Caletti?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Deb Caletti is a Seattle-based author, and National Book Award finalist. She won the Washington State Book award for Honey, Baby Sweetheart, which is just one of her fifteen YA and adult novels. Her latest is the YA novel A Heart in a Body in the World. You can see her talk about it in conversation with Martha Brockenbrough next Thursday, September 20th, at University Bookstore, and at the Lake Forest Park Third Place Books, on Saturday the 22nd.

What are you reading now?

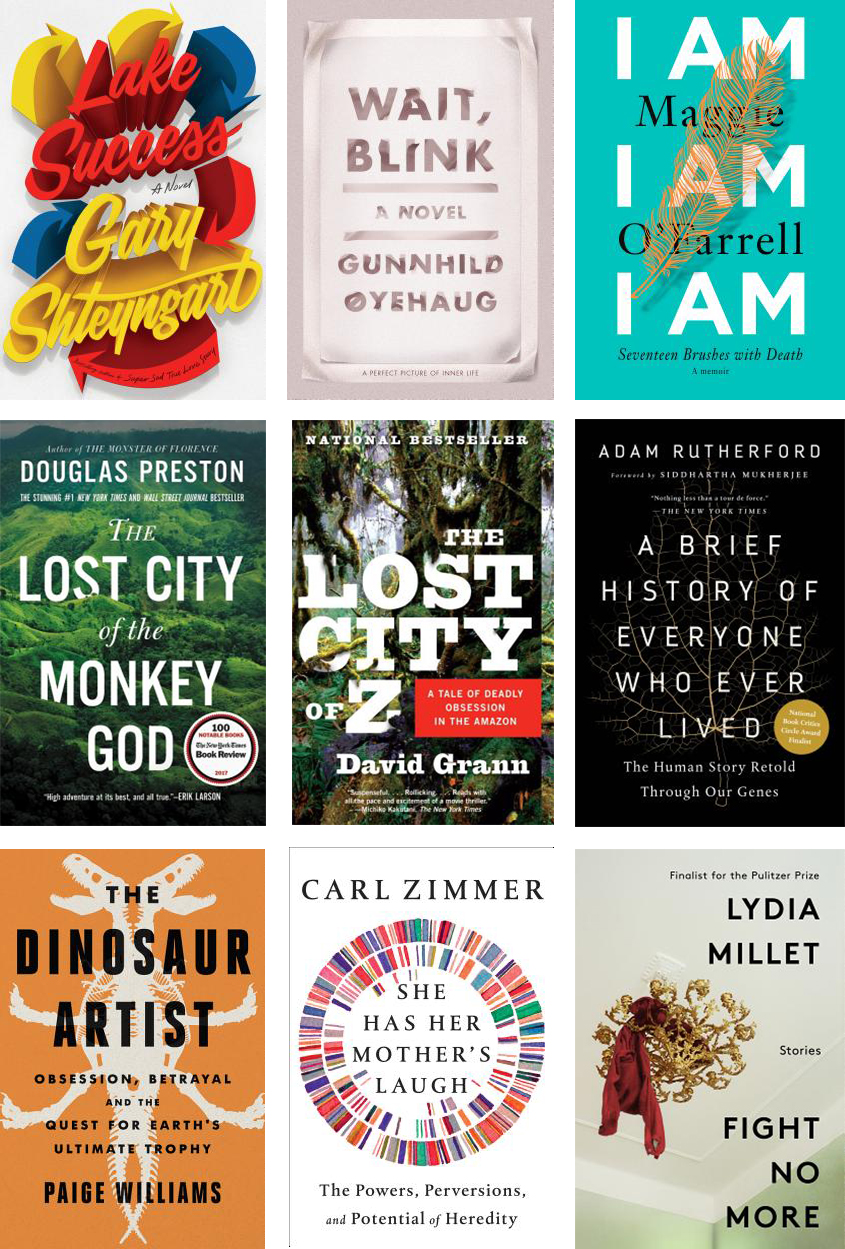

I’m reading Gary Shteyngart’s Lake Success. When I saw the review copy at BEA, I knew I had to have it, because I really liked Little Failure. At that point, I’d already gone past the number of books I could reasonably fit in my bag, but we are so greedy, us book lovers. It wasn’t quite the straw that broke the author’s back, but it was the ARC that literally broke the suitcase. I walked around two airports with the handle of my bag stuck halfway up, thanks to Lake Success, but it’s been worth it so far. Shteyngart’s so great at small moments of insight, and unexpected details that are surprisingly funny or vivid or poignant. He’s a compassionate writer, and I always love that. ou feel like it’s you and Gary there together in the crazy world of humans, and you’re better for it.

What did you read last?

I just finished by Wait, Blink, by Gunnhild Øyehaug. It’s a charming, odd, yet quietly profound novel of connected stories. I loved it. I was really happy to see it this week on the National Book Award’s inaugural longlist for translated literature. I also recently finished I am, I am, I am, by Maggie O’Farrell. Its subtitle is Seventeen Brushes with Death, and each chapter heading is labeled with the part of the body (lungs, heart, neck, etc.) related to the experience. I always know I’m in good hands as a reader when a book makes me want to write, and this one did that. It’s honest and intimate without feeling confessional, and the writing is beautiful in parts.

What are you reading next?

After I read The Lost City of the Monkey God, by Douglas Preston, I was so crazy about it that I read The Lost City of Z (David Grann), and then A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, by Adam Rutherford. Now, Sapiens, by Yuval Noah Harari is up next, as well as The Dinosaur Artist, by Paige Williams, and She Has Her Mother’s Laugh: The Power, Perversions, and Potential of Heredity, by Carl Zimmer. When I emerge from the deep jungle of history-plus-science, Lydia Millet will be waiting for me in the daylight of today, with Fight No More, her newest book of stories, which are all connected through a central character — a lonely Los Angeles real estate broker.

The Help Desk: Are we spiraling toward illiteracy?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com. The following is a republication of a column from 2015.

Dear Cienna,

Please settle a bet. My friend says our culture is spiraling toward illiteracy. He thinks we're devaluing language to a point where we'll soon only communicate through pictures, or video. I think we're more literate than ever before. I read more every day than I ever have in my life. Of course I read more websites than books, but I'm of the opinion that reading is reading. So who do you think is right? Are we becoming illiterate, or are we more literate than ever?

Fran, Redmond

Dear Fran,

Sure, more people may be able to fulfill the most basic definition of literacy but I disagree with you that "reading is reading." Like butt implants and Bible interpretations, reading varies wildly depending on the source. Is it great that a higher percentage of Americans can functionally read words, a necessity formed by our texting, emailing culture? Yes, but that doesn't mean they're critically engaging with what they read, or that the writing our culture is currently producing inspires intellectual curiosity (I'm specifically thinking about the sad state of journalism, which would best be encapsulated by a gif of people eating popcorn at the site of a grisly car crash. Also beautifully summed up by this debacle). As for your friend, please tell him or her that their argument is based on a false premise: words are not a cash commodity that can be devalued or replaced. For instance, there will never be a picture that can convey specific words like "lugubrious" and "malady" or even "uranium," which in pictorial form just looks like moldy bread. Since you are both wrong, I win your bet. You owe me a critical 500-word essay responding to an interesting article you've read recently and your friend owes me $20 and a gif of people eating popcorn at the site of a grisly car crash.

Please send both to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Pandemonium 2000

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Friday, September 14: Seattle Music Machine Salon

Ada’s Technical Books has an array of nerdy events for its customers. Friday night, the Seattle Music Machine Salon meets at the shop. The SMMS meetings feature “a presentation and a guided discussion on some aspect of making music with computers and electronics.” It’s intended for all skill levels, including amateurs.

Ada’s Technical Books, 425 15th Ave, 322-1058, http://seattletechnicalbooks.com, 7 pm, $5.

Future Alternative Past: Yes, but is it art?

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Or it didn’t happen

One picture is famously worth a thousand words. Which is just about the number I get to use writing this column. But I’m going to talk about pictures instead of giving you one — lots of pictures, as present in SFFH today and previously. And maybe in the future? Who knows?

E. Nesbit’s horror story “Man-Size in Marble” is the earliest example of visual arts in genre work that comes immediately to my mind. It’s told by a painter, and the story’s main focus is on two stone effigies that menace the narrator’s wife. Dolls also inhabit this particular uncanny valley, those sorts of denizens too numerous to name. 3D representations of the human form are almost guaranteed to creep readers out, though sometimes, as in Keith Donohue’s recent novel The Motion of Puppets they’re victims rather than villains.

Nor are horror and fantasy the sole SFFH subgenres where art figures. The hero of the two Ilario books by Mary Gentle is an intersex painter who celebrates the technological advances of their craft as this alternate history progresses through a Renaissance in which Carthage remains a ruling power. Artist June Costa narrates Alaya Dawn Johnson’s YA science fiction novel The Summer Prince, set in Brazil, about 400 years from now. With her doomed love Enki, Costa creates pieces that challenge the semi-Utopic status quo and further the underclasses’ resistance to immortality-fueled political stagnation.

Another SFFH novel in which art and revolution intersect is The City, Not Long After, by Pat Murphy. In a dystopic near future, post-plague San Francisco has become an artists’ colony, and its inhabitants find creative and magical ways to battle off an invasion of puritanical soldiers. Armistice, the second of Lara Elena Donnelly’s fantasy novels set in an imaginary world, features a burgeoning movie industry in its 1930s-ish milieu. Filmmaking provides the perfect cover for a intelligence operations against the Nazi-like Ospies. Is it also art?

Certainly according to many, myself included. But Catherynne Valente’s Radiance depicts an alternate universe in which cinema’s status as an art form depends on its compliance to an ossified code of values. A serious movie must be silent, and it must eschew the vulgarity of color. In 1986. Despite this attitude’s stodginess, the crew employed by Valente’s protagonist Severin Unck gallivants about the solar system freely to record her daring and gorgeous documentaries.

Visual art in SFFH, judging from my examples, tends to concentrate either on art’s ability to overturn authoritarian regimes, or on our emotional associations with its subjects, or on the technology behind its techniques. Then there’s Cortez on Jupiter by Ernest Hogan, which does all three: a guerrilla muralist from LA is brought to Jupiter to commune with aliens via his wildly abstract art and exploits Jovian gravity via an expanded repertoire of painting techniques.

My least favorite inclusions of visual art in SFFH are those that use it as a metaphor for something else: for writing (far too frequently), or, God forbid, religion, as JRR Tolkien seems to have done in his 1939 short story “Leaf by Niggle.” Let art be art, I say. Even, or maybe especially, art that’s merely imagined.

Recent books recently read

South African author Imraan Coovadia’s latest novel, A Spy in Time (California Coldblood), blends a film noir aesthetic with time travel in an Afrofuturist challenge to the paradoxes customarily dogging this well-worn SFFH trope. Enver Eleven, recent recruit to the time police of “the Agency,” obsessively studies recordings of the past so he won’t depart even slightly from known historical events. For his first mission he’s sent to Marrakech in 1955, which is an admittedly problematic period for a black man such as himself. He’s only supposed to observe, though, making this an ostensibly easy assignment--till his accompanying superior is disastrously killed. He then has to scramble back and forth between the 20th century, his home base in a post-apocalyptic 23rd, and an even more depressing far-future outpost on Jupiter. He also has a ringside seat for the Second End of the World, which he was charged with preventing. Phantasmagoric scenes of the descendants of black miners wrapping themselves in the skins of hunted whites and of AI-operated bulldozers breaking through the dome walls surrounding iridescent chronogates nicely illustrate Coovadia’s twisty plot and ingenious resolution.

Rosewater (Orbit) by rising star Tade Thompson is also a mash-up of the noir/hardboiled detective genre with SFFH, and also arguably a work of Afrofuturism. Though born in London, Thompson is the child of Yoruba (West African) immigrants, and 99.9% of the novel’s action takes place in Nigeria. The trope he tackles, though, is an alien invasion. Which as I write this is apparently already in progress. Thompson’s genius in displacing his tale of successive xenobiological attacks from the West onto the developing world is matched by his breathtakingly smart prose. Always crisply conveying both vivid sensations and ineluctable meaning, Thompson describes extra-dimensional sexual encounters, the technical requirements of invisibility, the brutality of telepathic interrogations and more in this deeply engrossing book. Rosewater undeniably deserves its Nommo Award for best novel, and its forthcoming sequels may win the author a second Nommo — as well as earning him many other awards. And rightfully so.

Couple of upcoming cons

Seattle’s GeekGirlCon celebrates non-dudebro SFFH in all its glory. Citing Marie Curie and Ada Lovelace as foremothers of today’s science-minded fangirls, GeekGirlCon organizers are putting on their eighth annual convention honoring “women and other underrepresented groups.” Expect panels and workshops (though an exact schedule hasn’t been released yet), an art show, a floor full of gaming, and vendors of costumes, comics, jewelry, and more. Expect activism and warmth, experimentation and acceptance.

Sirens also celebrates women-identified lovers and producers of SFFH, with a strong emphasis on fantasy. Over its ten years of existence it has done this at a variety of venues — for the last few years at a couple of luxury resorts in Colorado, and before that at one in south central Washington State. As the choice of accommodations indicates, Sirens is a bit spendy. The price of attendance ranges from $225 a year out, to the current cost of $275, to $300 at the door. That price includes two lunches; your transportation, your hotel room, and a few of the workshops are sold separately. Scholarships are available, though applications for those were due back in May. Part academic conference, part sercon, Sirens reportedly packs googobs of goodness into its three-day program. Which it should.

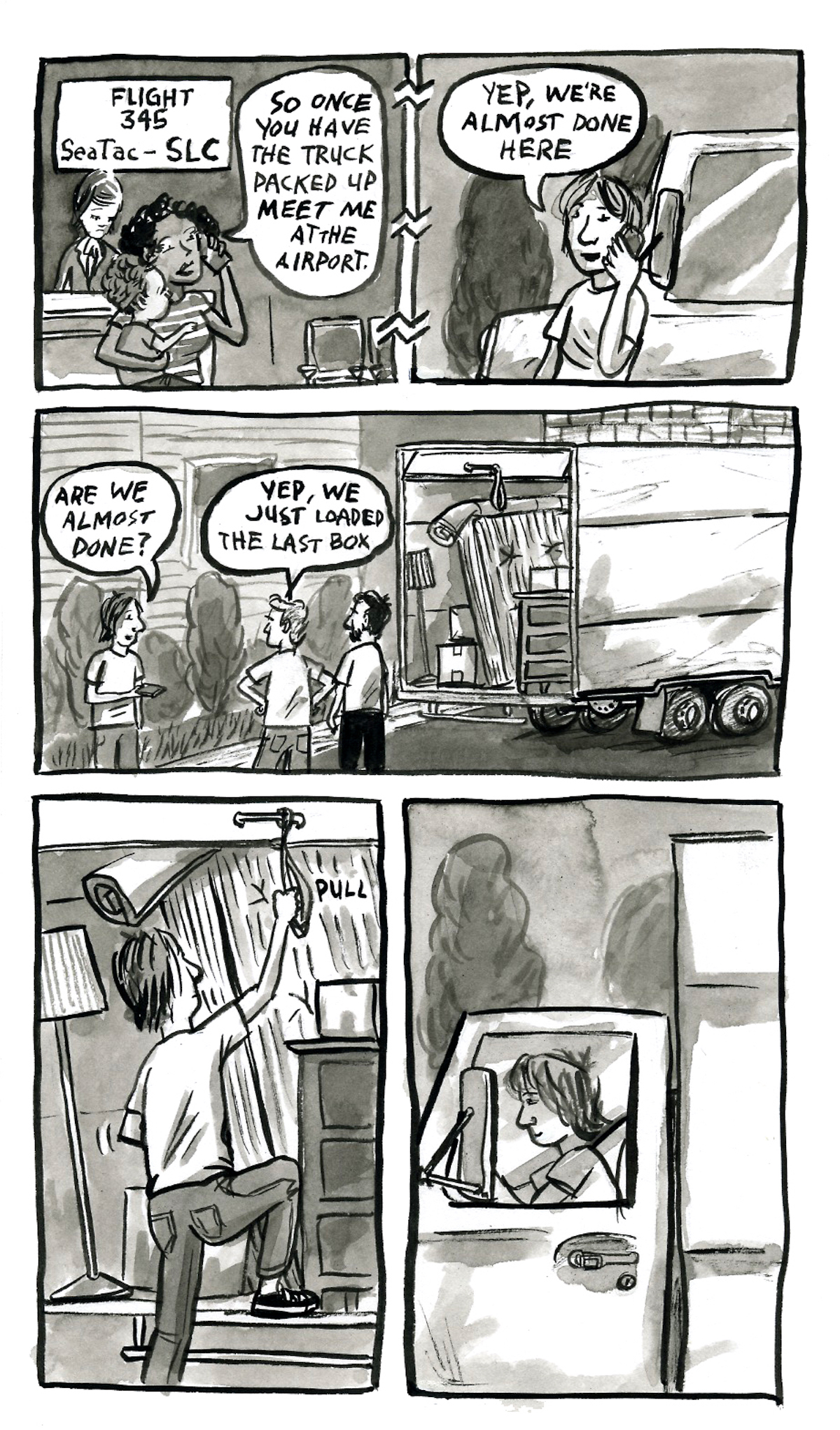

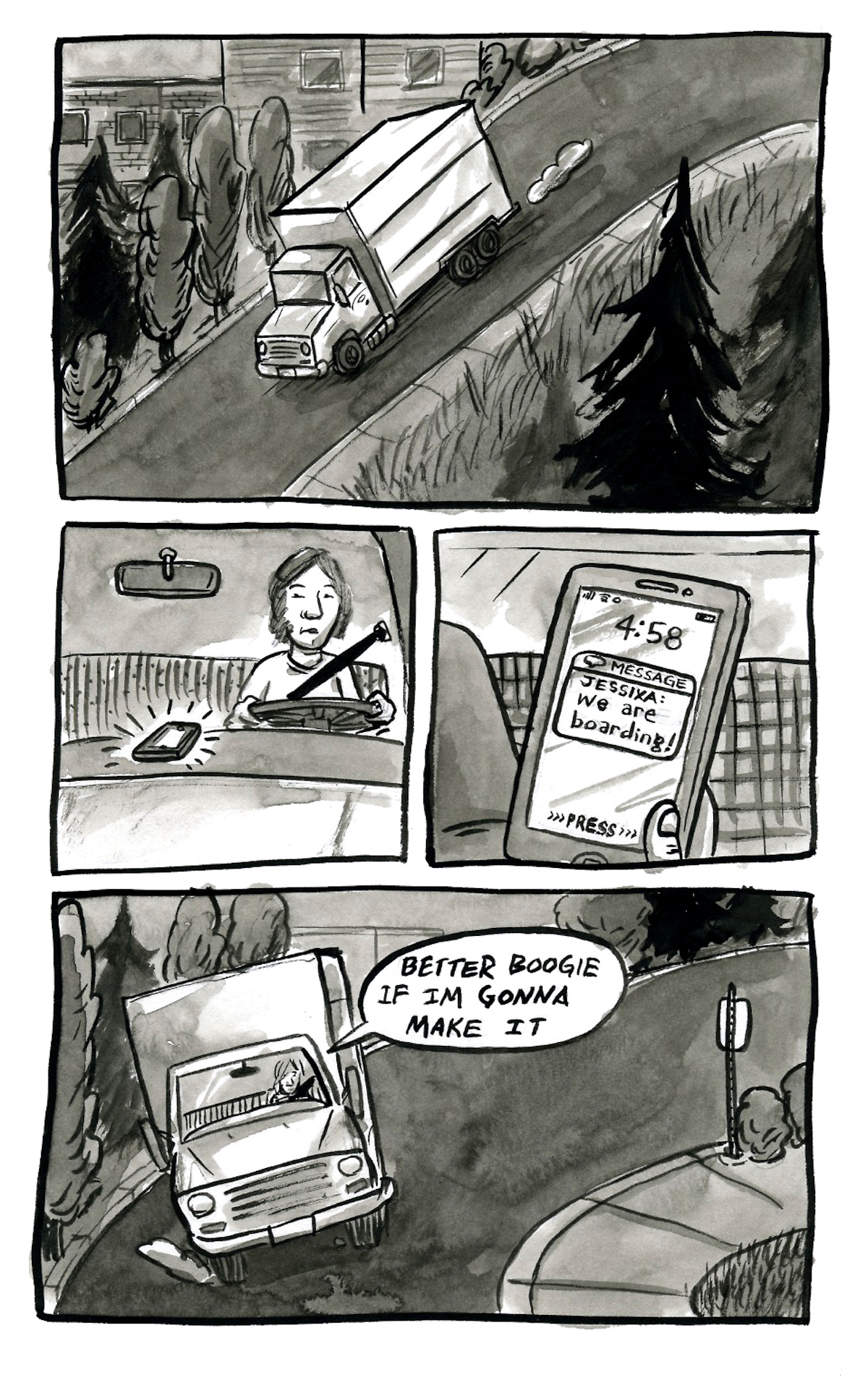

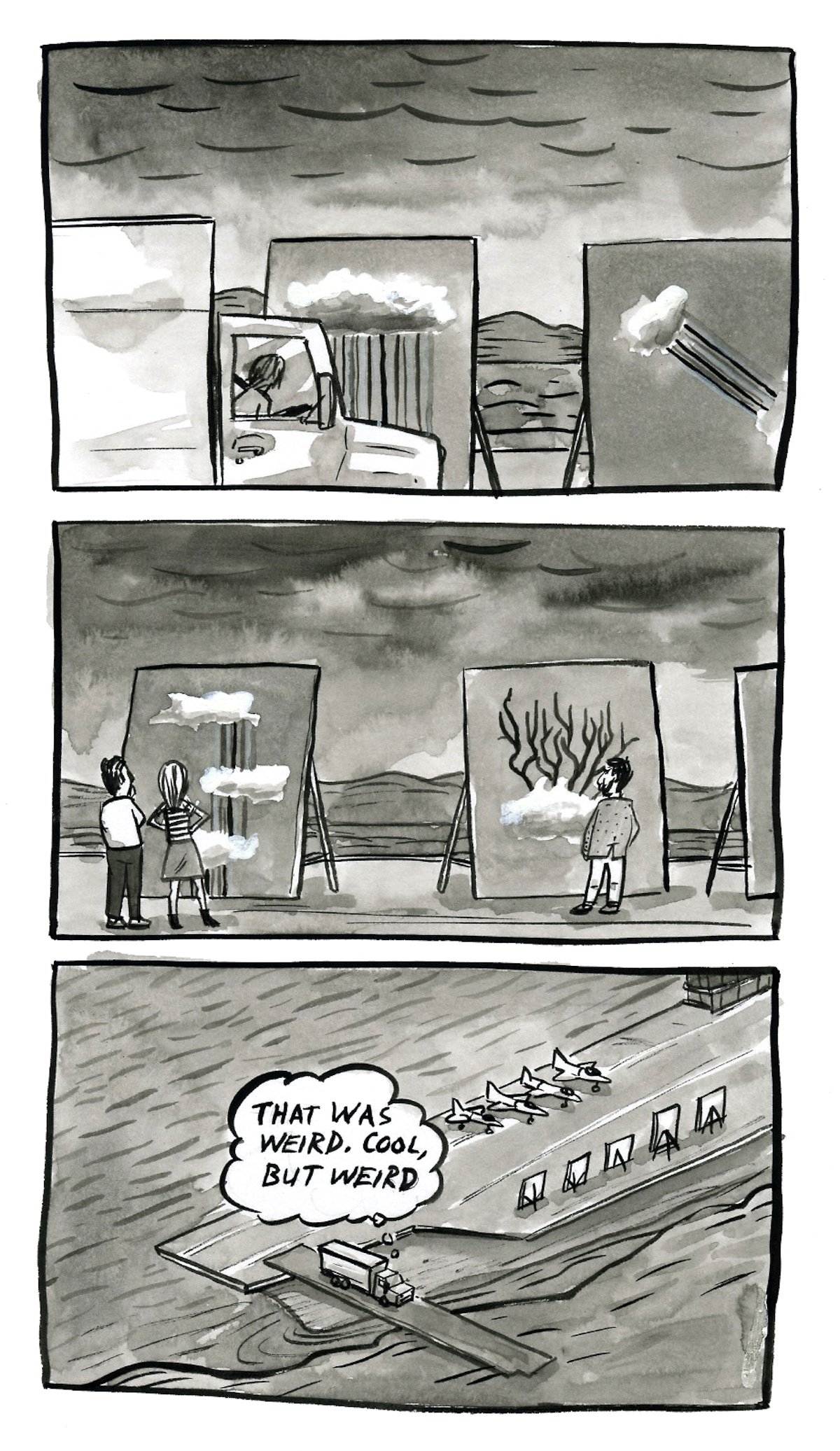

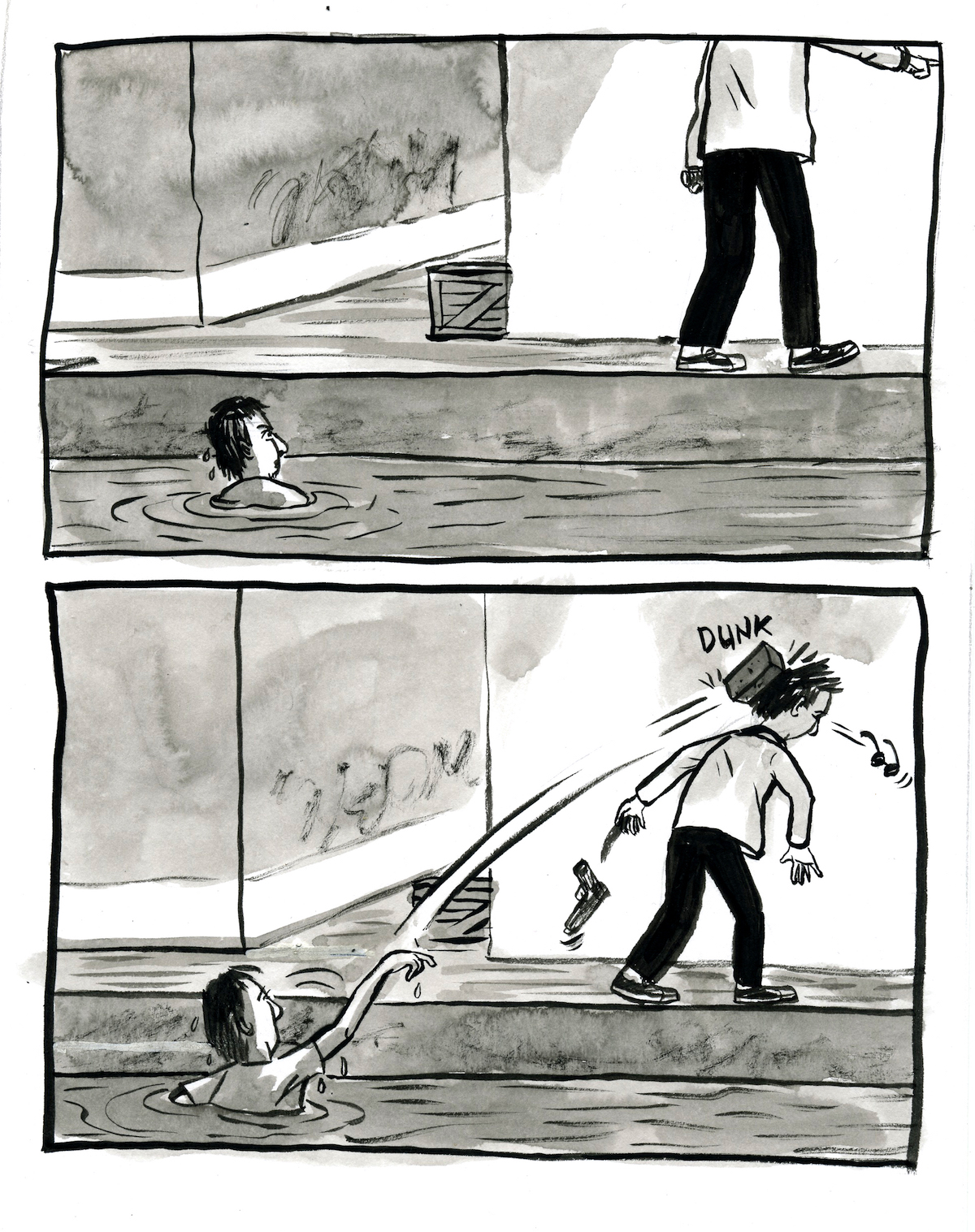

Thursday Comics Hangover: Wherever you go, there you are

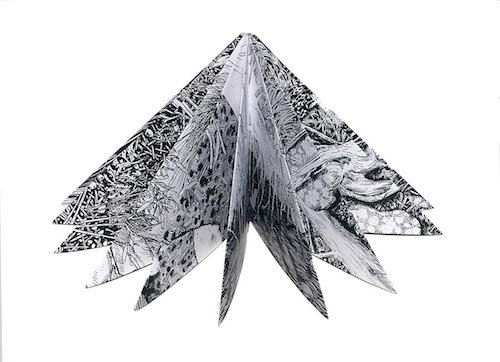

Short Run cofounder Eroyn Franklin's latest comic, Vantage #3, comes in a triangular envelope that is illustrated to look like a yurt. Inside the envelope, Franklin explains that this issue of Vantage is a record of her time at a monthlong residence at Caldera Arts in Oregon.

Franklin hiked a lot in her time at Caldera, and during those hikes she would stop and look straight ahead, and then at the ground beneath her. Vantage captures those two views in a beautiful little triangular minicomic that the reader can unfold and read in several different ways.

As a viewer, you have a choice. You can pull back the corners of each page to unveil a tableau that Franklin witnessed — a creek in a densely wooded area, or a waterfall, or a crater lake. Or you can leave the book in a kind of free-standing Christmas tree shape, which Franklin calls "comic sculpture."

No matter how you choose to read Vantage, Franklin's detailed black-and-white illustrations will move you. The conceit of combining a panoramic view with a close-up of the ground beneath her feet — the land ahead, the land below — is especially moving. Who hasn't been surprised by the beauty of nature, only to look down to make sure they're still connected to the earth?

With no words on the actual comic, Franklin manages to portray one of the most complex joys of nature. Even the loftiest tree still has a complex system of roots to keep it connected to the dirt below. Amateur hikers might value those vistas over the ground underfoot, but they're missing the point. There's just as much complexity — and beauty — under our feet as there is in front of our faces. It's all one piece.

Book News Roundup: Spokane alt-weekly to publish serialized novel

Spokane alt-weekly The Inlander (where, full disclosure, I worked as a freelancer for a few years) has announced an exciting new development. Starting tomorrow, they'll be publishing serialized installments of Miller Cane, a new novel by Sam Ligon. Congratulations to The Inlander for rethinking the idea of what an alt-weekly can and should do.

In sadder alt-weekly news, the owners of the Missoula Independent closed the paper down suddenly yesterday.

[Independent owner] Lee [Enterprises] Regional Human Relations Director Jim Gaasterland told Independent staff in a message Tuesday the company closed the newspaper that day and to schedule an appointment to retrieve any personal belongings.

Third Place Books has announced a whole new events staff, including a brand-new position called "children's books outreach manager," which will "coordinate programming and events for young readers, both in schools and in-store."

Hey, here's some Amazon news that isn't terrible for literature in general for a change: the online retailer has stopped selling nine self-published books by the atrocious "Men's Rights Activist" known as Roosh. The books are often characterized as "how-to manuals for sexual predators." Roosh does still have several books online. Before you whine about freedom of speech, please recall that Roosh is perfectly capable of selling his books by himself. Amazon didn't owe him a platform, and it's awful that they allowed him to sell his books for as long as they did.

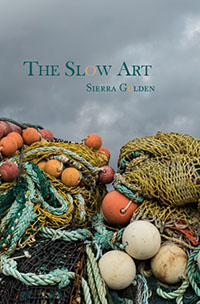

Sierra Golden is finding her way in the world

Our September Poet in Residence, Sierra Golden, is at the very beginning of what looks to be a long and important career in poetry. Her debut collection, The Slow Art, was just published this month by Bear Star Press, but she writes with the confidence and the economy of a poet twice her age. This is not something you see in a young poet: Golden inherently understands that what you don't say in a poem is just as important as what you do say, if not more.

"I was always the student who was interested in poetry, from elementary school through high school," Golden tells me over coffee. But she didn't consider herself a poet until college, when she took a workshop with former Washington state poet laureate Tod Marshall. "I still think it's the best workshop I've ever had," she says.

The first piece Golden turned in for the workshop was a poem about fishing. "I spent eight summers working in a commercial fishing boat in southeast Alaska," she explains, "and that became the focal point of most of my writing for a really long time."

Golden is from a fishing family in rural Washington state — her dad has worked as a commercial fisherman for four decades — and when she worked salmon season one summer to pay for school, "I fell in love with it — just being outside, doing something that gives you really immediate feedback. Either you catch or you don't."

The "eternal optimism amongst fishermen" culturally spoke to Golden, but when she was out on the water, she also felt "an elemental connection to the natural world," and that connection gave her a sense that she had a place in that world. Poetry, then, is how she learned to communicate all these elemental emotions. She loves the form for its way of "condensing life into something small and measurable and meaningful and musical."

Her early influences include Sharon Olds, Jack Gilbert, and (on the more contemporary side) Matthew Dickman. Her reading inspired her to pursue an MFA in poetry at North Carolina State University. Golden wasn't sure at that time if she'd be a poet, but "I knew that [the MFA] would be formative and I knew that if I didn't do it then, I might not ever do it."

After moving to Seattle, Golden felt more and more comfortable thinking about herself as a writer. She took a job as a communications associate at an important local nonprofit. "Working at Casa Latina has probably been more affirming than anything else" in terms of helping Golden think of herself as a writer "because I do a lot of the external writing for them. The staff has been very supportive and flexible over the last four years so that I can work on personal projects."

Seattle has embraced her. Golden was selected for Hugo House's Made at Hugo program, which provides educational and resource support for a cohort of young writers. She finds inspiration and draws strength from many Seattle authors including Anastacia Renée, Daemond Arrindell, Elizabeth Austen, and David Wagoner, and she thinks "more people need to know" Bellingham author Nancy Pagh, a creative writing teacher at Western — particularly her book No Sweeter Fat.

Golden is still coming to terms with herself as a Seattle writer. As much as she loves the city, "I still crave a smaller, quieter, less fast" lifestyle like the one she had growing up in rural Washington. She's branching out into other forms, too. "I'm working on a novel," Golden says, "which I never thought I would do and was never interested in."

Still, Golden is getting "the itch" to return to poetry. Writing about fishing, she says, "made me feel like I was cheating or something because it's so visceral and it's really easy to write about it." While the poems in The Slow Art at times feel like journalism, her "next challenge," she says, "is going to be how to write about something less concrete that has the same meaning." Considering all that Golden has accomplished so far, it's obvious that she'll find her way. She always does.

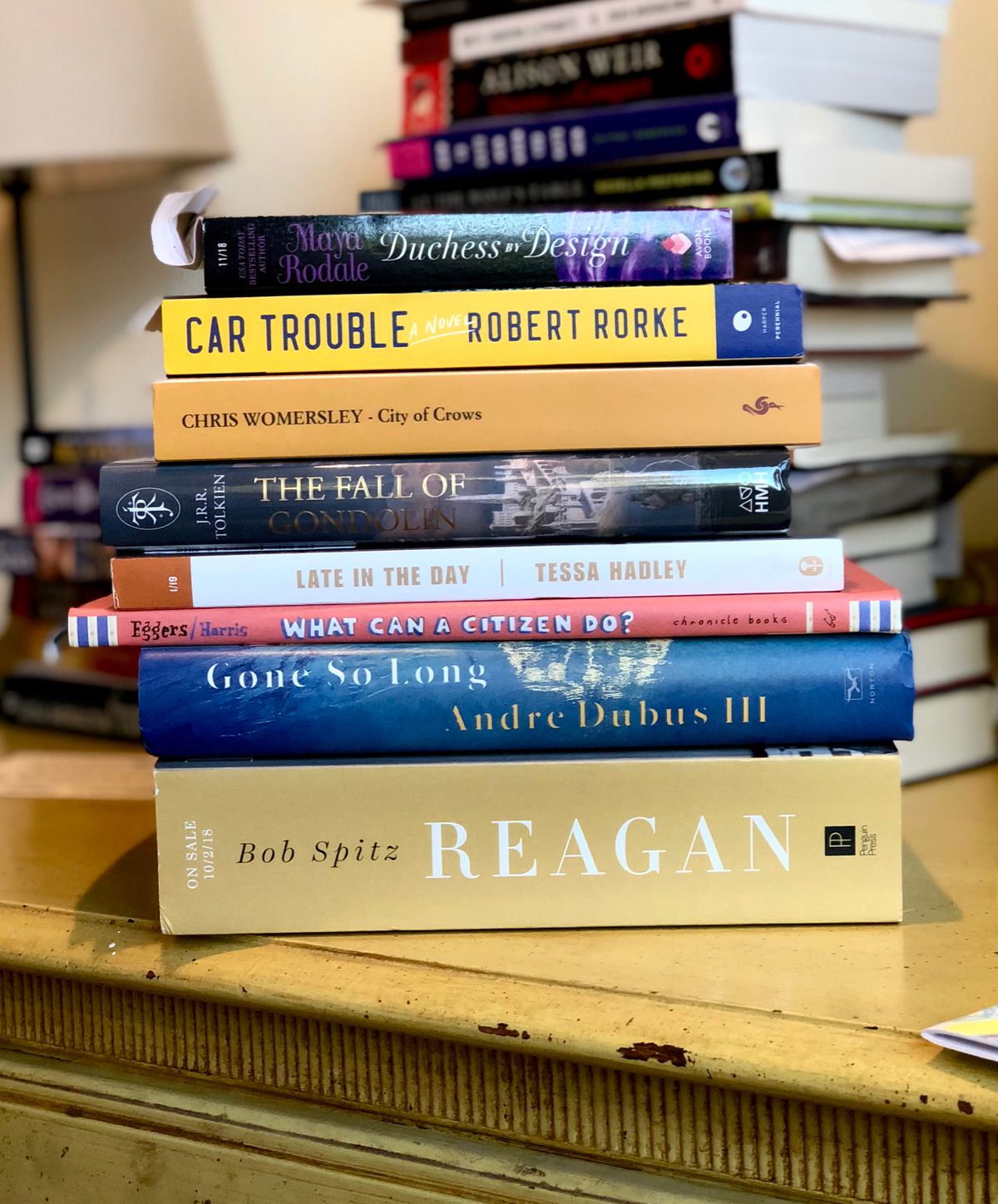

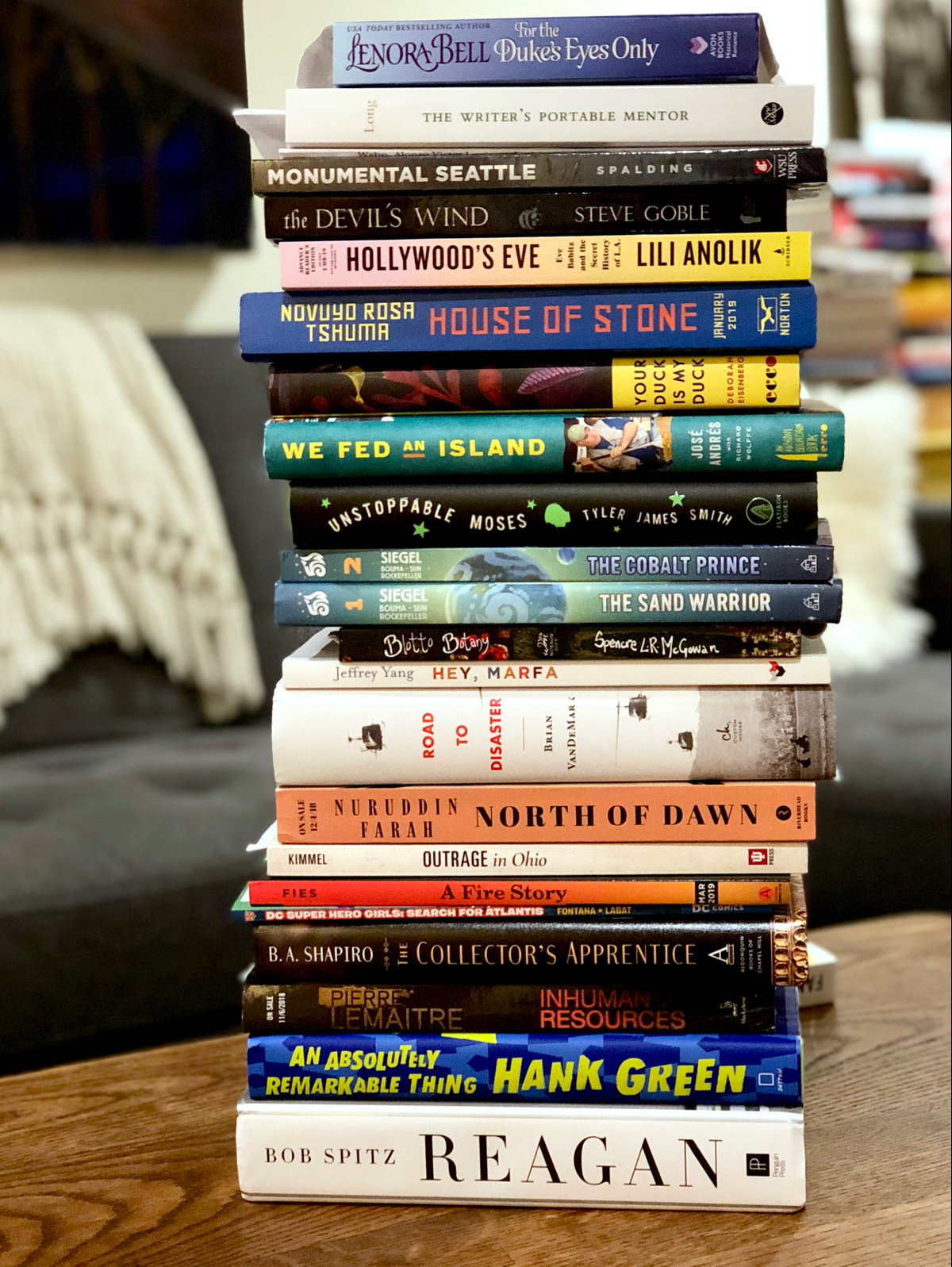

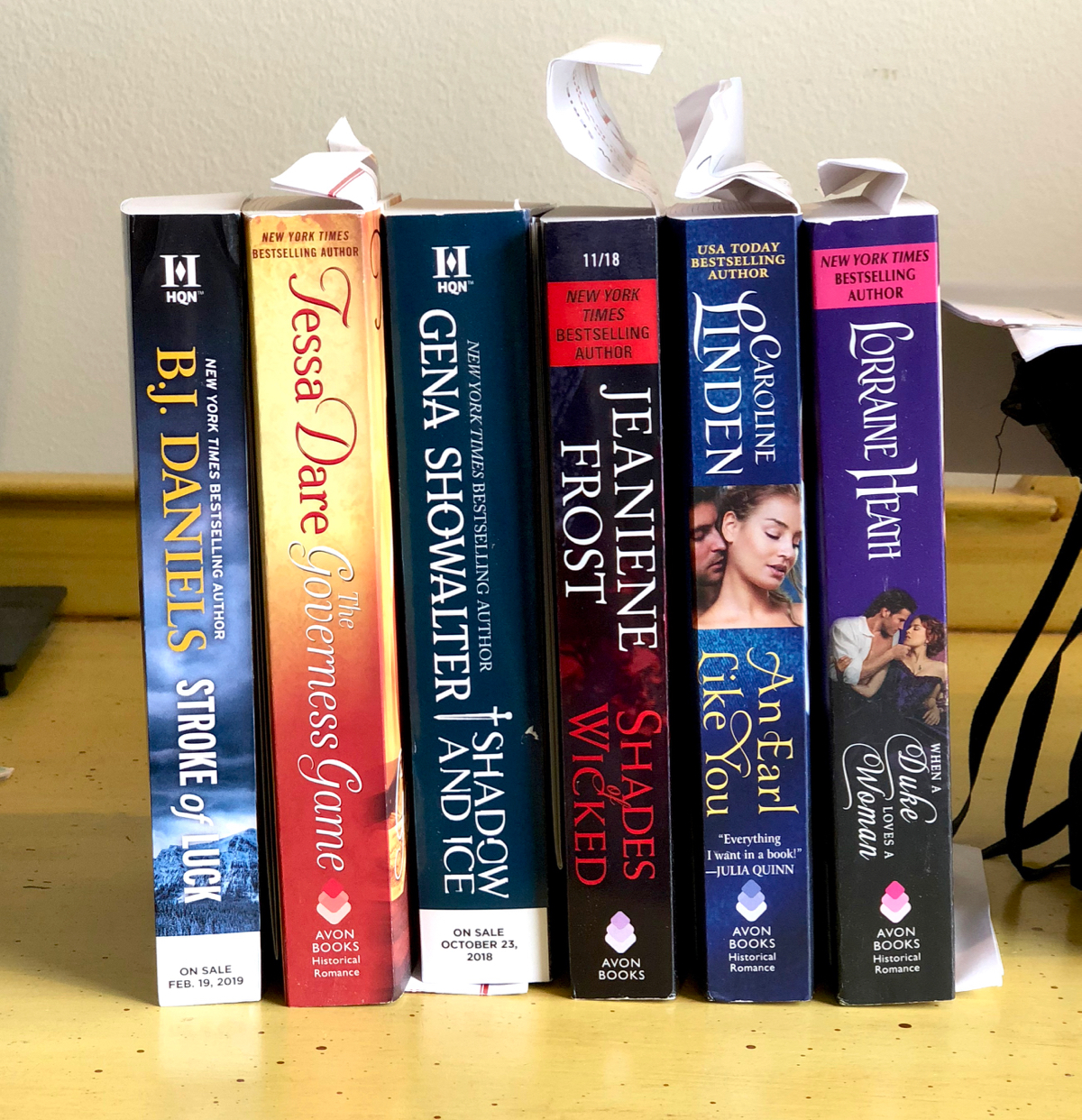

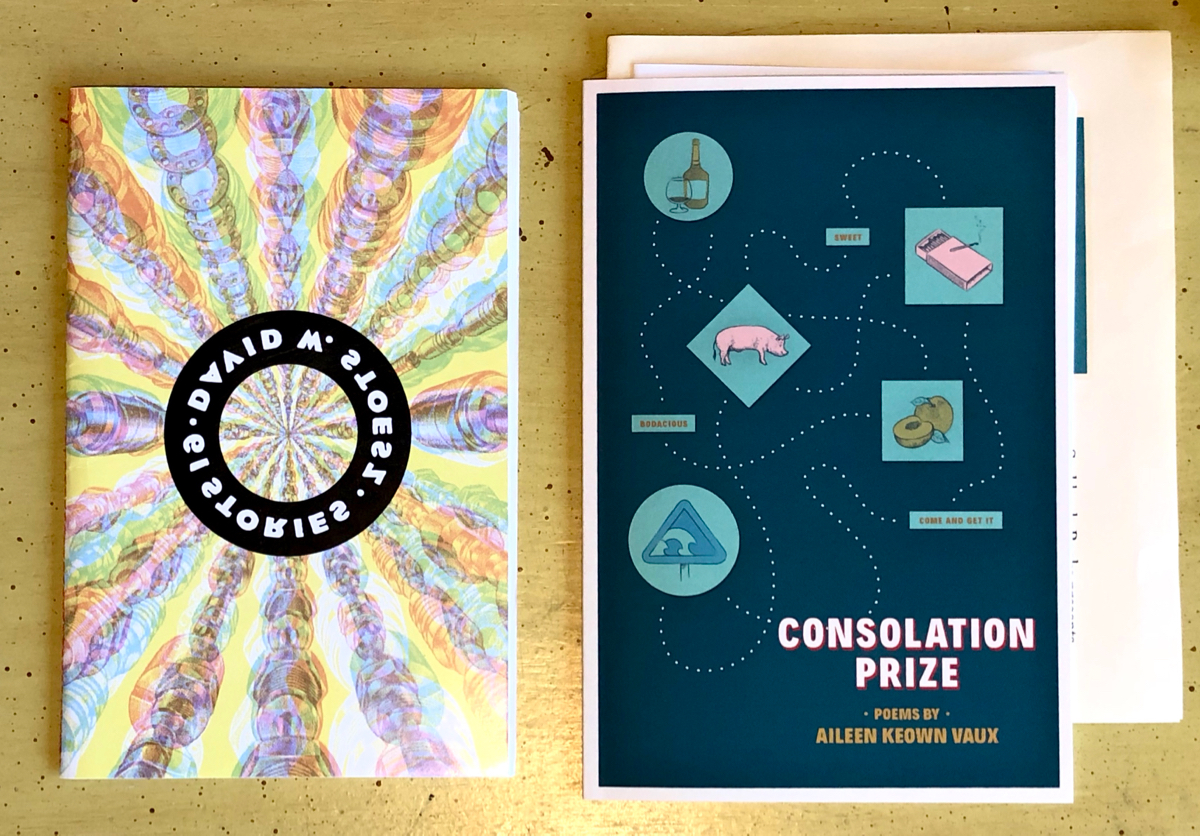

Mail Call for September 11, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Yesterday, the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival announced that they're now splitting studio space with Paper Punch Press and Hocus Pocus Press in Georgetown:

We envision a welcoming, accessible, high-quality, experimental print and publishing collective that is open to all – let us help you make some unique books and prints! Find us at 5628 Airport Way S; Suite 175, Georgetown.

Short Run does host events all year long, but year-round studio space is a big deal. Additionally, the fact that Short Run is now so close to the Fantagraphics Store means that Georgetown could now be Seattle's official Comic Book District. We'll be talking more to Short Run's organizers in the weeks ahead to see what they have planned for the space.

American ugly

Published September 11, 2018, at 11:55am

What is the right way for authors to approach an especially horrifying time in American history? Is there a wrong way to write about recent tragedies?

Working Too Hard

For five nights a fat banana slug has come to visit me,

chugging up the window, stopping just at eye level.In front of the chair where I sit to write most mornings,

he sleeps for the night. Or does whatever it is slugs do.By sun up, he’s gone, leaving in his place a tiny pile of shit.

It’s hard to look past this. Drinking my tea and writing,imagining this shiny, slimy creature I’ve come to call friend

exposed on a field of glass, making his morning constitutional.With no real predators—not even the bears or skunks

will partake of him—he appears entirely unworried.His simple body, tentacles, mantle, anus, upsets me.

How easily it does exactly what it’s supposed to!

Talking about the birds and bees in the #MeToo era

We're delighted to have Rough on the site and excited to let you know about several chances to see her speak, coming up in September and October.

On September 11, Town Hall is hosting a conversation between Rough, parenting expert Amy Lang, and columnist Nicole Brodeur on how to raise children who handle consent, gender, and equity better than today's grown-ups.

On September 20, Rough is paired with author KJ Dell’Antonia at Phinney Books for a conversation that should be even more personal, direct, and revealing.

On October 29, she's speaking at the Redmond Library (King County Library System) solo, which should be the perfect chance for deeper conversation about her current and past work.

Get more information about both events on our sponsor feature page, then put them on your calendar.

Sponsors like Bonnie J. Rough make the Seattle Review of Books possible. We're almost sold out through 2018, so grab this chance to get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 10th - September 16th

Monday, September 10: The Mere Wife Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, September 11: Birds, Bees, and #MeToo

Seattle Review of Books contributor Bonnie J. Rough, who recently published a new book titled Beyond Birds & Bees: Bringing Home a New Message About Sex, Love, and Equality, will lead a discussion about raising children in a time of massive gender inequality and the #MeToo movement. She'll be joined by Amy Lang and Seattle Times columnist Nicole Brodeur. Phinney Center Community Hall, 6532 Phinney Ave N, 783-2244, http://www.phinneycenter.org, 7:30 pm, $5.

Wednesday September 12: Fight Like a Girl Reading

Seattle's own Shout Your Abortion co-founder Amelia Bonow joins Australian writer Clementine Ford for a discussion about feminism in 2018. Fight Like a Girl is a book that expands on Ford's popular TED Talk about rape culture, among other topics. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, September 13: Not Even Bones Reading

The publisher describes Rebecca Schaeffer's young adult fantasy as "Dexter meets This Savage Song, which probably doesn't make the author feel nervous or annoyed at all. It's about a girl who sells body parts in a world where magic exists. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, September 14: Seattle Music Machine Salon

Ada's Technical Books has an array of nerdy events for its customers. Tonight, the Seattle Music Machine Salon meets at the shop. The SMMS meetings feature "a presentation and a guided discussion on some aspect of making music with computers and electronics." It's intended for all skill levels, including amateurs. Ada’s Technical Books, 425 15th Ave, 322-1058, http://seattletechnicalbooks.com, 7 pm, $5.Saturday, September 15: Three poets

Quenton Baker, who is the current Open Books Poet in Residence, joins former Seattle Youth Poet Laureate Lily Baumgart and Washington State Poet Laureate, Claudia Castro Luna for a chill Saturday night reading. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Sunday, September 16: The Lost Art of Reading Reading

Subtitled Why Books Matter in a Distracted Time, David Ulin's book is a call to celebrate the act of reading in a world that seems dead set against the act of paying attention to anything for more than two seconds. Ulin, who was the editor of the Los Angeles Times's book review section, is just the person to answer this question. I'll be joining him onstage to talk about the book and literary criticism and possibly the impossibility of focusing on books in a time when Donald Trump is president.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: The Mere Wife reading at the Seattle Public Library

Maria Dahvana Headley has had something like twenty writing careers packed into a single life. Back when she lived in Seattle, she published a memoir titled My Year of Yes, about an experiment in which she said yes to every single offer for a year. (Before you roll your eyes at the premise, you should know that this was at the very beginning of the "my year of..." craze, before the market became oversaturated in stunt memoirs.)

Headley's written young adult science fiction novels and alternate histories. She's won major awards for her short fiction. She's co-edited an anthology with Neil Gaiman. She's published and produced plays. Every few years, she reinvents herself, and every few years she seems even more comfortable in her own skin.

With her latest novel for adults, Headley proves that her ambition is as wide-ranging as her talent. The Mere Wife goes back to the roots of literature with an audacious twist: it's a retelling of Beowulf, set in suburban America. Headley is manipulating myths and legends with the confidence of a writer twice her age, and the reviews have been euphoric.

Tonight, Headley returns to Seattle for a conversation with another hometown literary hero — Nicola Griffith, author of Hild and So Lucky. The two writers have a lot in common: they tackle big ideas with zero apologies, and they both approach genre with a beautiful and ornate prose style. This should be a night to remember.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for September 2, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Needles and the Damage Done

Aaron Timm’s essay on New York’s “supertalls” — skyscrapers that crest 1,000, even 1,500 feet, intended primarily for residential use — made me wonder about Seattle’s own trajectory. The Columbia Center is still our tallest, at just under 1,000, and nothing in the works will compete for the title. The proposed 4/C project would have taken us over the 1,000-foot mark, but the FAA relentlessly cut it down to size. Little has been heard from disheartened developer Crescent Heights since 2016.

But pure height isn’t the story. Residential height is, and the possibility that supertalls will host the superrich, an earthly Elysium. It’s an eerie JG Ballard-ish idea — that the tech elite might simply, literally, rise above the rest of us. We shape our spaces, and they shape us in return, for better and sometimes for worse.

Cities change, of course they do; but what matters is for whom they change, and at what cost. Demolition, displacement, accommodation, and compromise are the conditions of urban life. But the city of the supertalls is engineered to take its denizens beyond these conditions, to deliver them into frictionlessness. It’s a place of moonshot wealth, skinny buildings, no resistance, and no surprises; a city that’s not really a city at all, but its own comfortable superstate.

On Not Being Able to Read

When we think about how we read these days, it’s mostly to despair over our deteriorating attention spans and hurl curses at our internet overlords (no irony here for the Sunday Post). But maybe our reading brains are more resilient than we think, more tied to who we are and what we value, not so ready to release us.

Law school tried to teach Tajja Isen another way to read, but her reading brain fought back, and eventually led her away from the law. It’s a lovely idea, rendered without sentiment here, that the way we read (not just what we read) can be part of our resistance — to wrong choices, to wrong ideas, to ways of being that are inimicable to who we are.

A few nights a week, I’d make a feeble attempt at proving the world wrong, swimming up through my exhaustion to pick up a novel and push through its pages. Sentences were newly terrifying; tiny minefields of meaning where I might miss a principle I’d later be called upon to produce, freshly plucked. I labored for months over what had once taken me days. I told myself that this was pleasure; that these motions were sufficient proof that I hadn’t allowed myself to be drained of joy and filled with something else.

Why the President Must Be Impeached

If I ever have to walk through a swamp at night, stepping uncertainly for solid ground and listening for the quiet splash of a reptile in the water nearby (does anyone else find Disneyland’s Jungle Cruise infinitely more terrifying than the jovial Haunted Mansion?), may Rebecca Solnit be my guide. Here she oulines in crisp, certain paragraphs the case for impeaching Donald Trump, taking us step by step through the murk of corruption and distraction of the past few months. It’s hard to think of anyone other than Solnit who could use these giddy, run-on sentences to both recreate the desperate feel of the chaotic news cycle and map our way through it.

It was hard to remember, with the over-the-top corruption of Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort frothing up like a badly poured beer, to keep track of the conspiratorial roles of Roger Stone and George Papadopoulos, long after everyone had forgotten all about Carter Page, who’d been reported as a foreign agent by US intelligence while he was toddling about Russia and maybe making some secret deals with the oil company Rosneft, or Michael Flynn, who’d been the first to be fired for corruption, and who’d been convicted for lying to the FBI about his contacts with Russia, but whose sentence was being held up because he might have further use for the Special Counsel investigation.

Whatcha Reading, Maria Dahvana Headley?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Maria Dahvana Headley, is an author, editor, playwright, screenwriter, and monstermaker — to quote her website. She's a bestselling author of the YA space fantasy Magonia, and most recently, The Mere Wife which re-imagines Beowulf in the modern age. She once called Seattle home, but now writes from new York.

A night not to miss: this Monday, September 10th, Nicola Griffith will be interviewing Maria Dahvana Headley in the Microsoft Audtiorium at the central library, a joint production of the Seattle Public Library, and the Elliott Bay Bookstore. Starts at 7:00pm.

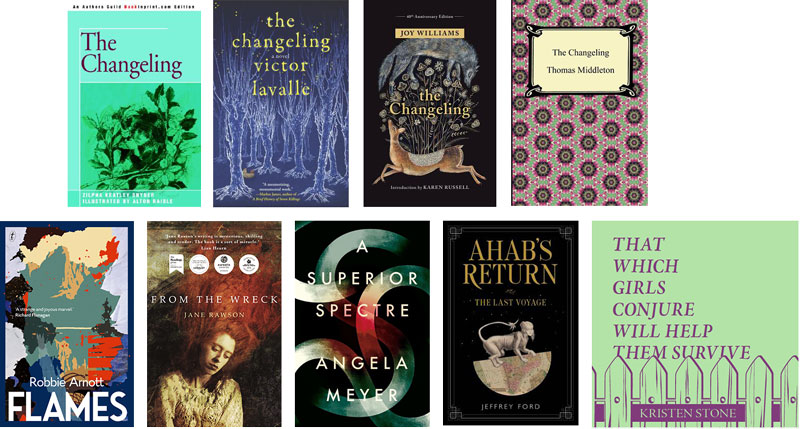

What are you reading now?

Sometime in recent months, I discovered that I had four books called The Changeling on my shelves, which tells you something about the kind of person I am. I'm definitely not a changeling — I actually come from a weirdo magic family, and was never trapped among Muggles — but the moment I learned the term, age 8 or so, I was like...OMFG LEMME BE A FAIRYLAND PROBLEM CHILD. I learned about changelings from the Zilpha Keatley Snyder novel (1970), which is actually about class, creativity and friendship between girls, but which deals in the story of an artistic, brilliant, and very poverty-stricken girl who believes she came from the fairies rather than from her own family. I loved Snyder's books because they were about people like me, wandering around rather below the working class, rather than about children who came from money, manses, and well, WWII-era England, however perilous. I was interested in the longform peril of poverty and daily life. Snyder's work was all rooted in imaginative games, and I'm currently also reading this badass academic paper by Cathlena Martin, about how Snyder's The Egypt Game as well as other children's lit preceded and plausibly influenced Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games (which are usually credited to influencers like Tolkien). So, back to Changelings, various versions: Last year, I read Victor LaValle's brilliant novel version in which a couple deals with a horrific and agonizing child-swap. And now, right now, I'm reading Joy Williams's The Changeling for the first time, though I've been a fan of Williams's work for years, beginning with The Quick & the Dead, another book about fiery, difficult, magical friendships between girls. Williams's Changeling is thoroughly my kind of book — the kind that can't be compared to anything, but hey, say, Malcolm Lowry mashed with the surrealist eerie (surreeriealist?) plots of Shirley Jackson. In it, a floatingly aimless mystic of a young woman falls into a strange as fuck clan mostly made of children, but run by an abusive man. Williams is killingly precise and poetic, and each sentence makes me suffer, because each paragraph made of these sentences is basically a novel unto itself. For example: "...after the first (child), Aaron truly believed himself to be a sinful man. He invented the Devil for them then. Emma didn't care. She had always been below good and evil. Her magic had never been anything trivial. No burying of teeth or hair. No communions of blood and excretions. If Aaron chose to believe in something as trivial as the Devil, Emma allowed him his foolishness." This is in a recounting of the child tribe's story of their origins. The particularity of it! The simplicity of it — below good and evil! — and a couple of pages later? "It was Emma that seemed to have an excellent relationship with God. They were like two bears in the same den. Dismissing faith, Aaron took up with superstition." Ahhhh, I'm dead. It's like a four paragraph dissertation on the labyrinthine ways of toxic masculinity. I have to read this book in short bursts. Right now, I'm halfway through, and panting. The last Changeling on my shelf is Thomas Middleton's play from the 1600's, but apparently I could also read some Ōe. I'll no doubt one day give in and write a changeling story of my own. If you let a story concept gestate for 33 years, you know you have to surrender and give it to the fairies. Fine, fine, I'll give birth to this story. Oh, uh-oh, what is this in the cradle?...Welp.

I mean, that's what this whole profession looks like from the inside.

What did you read last?

Last book I read was in Australia, because I was at the Melbourne Writers Festival, and during it, I slunk into several bookstores ostensibly to sign my own books, but really to paw at books I hadn't yet seen in the US. So, on the flight back to the US a few days ago, I read three in a row, and they had things in common, and I was excited! Beyond the Wreck, by Jane Rawson, is intensely researched historical fiction but also has a cephalopod shapeshifting alien, so. SO, it's remarkable. It's got many different POVs and a whole lot of weird, but the weird is firmly rooted in the difficulties of having a mortal body, and conversely in the difficulties of being a wandering lonely creature whose body doesn't work out well on our planet. It's dark and beautiful, and puzzling and unresolved, and I was way into it. Then, I read Flames by Robbie Arnott, which begins with a family of women resurrecting post-cremation and living on for a few days in human/botanical hybrid format, and takes us on a wander through a world in which tuna fishing is done only by fishers who've bonded with seals, fire is a father, and love of creatures and landscapes is a motivating force. Then I read A Superior Spectre, by Angela Meyer, which is a dual/linked timeline story about a near-future dying man from Australia who uses a device to connect his mind to the life and mind of a young woman in 1860's Scotland. He ends up haunting her, but this book is complicated and intriguing in a host of ways, not least because of the way it deals with sexuality, ethical responsibility, and again, toxic masculinity. All these books had in common the notion of melding one's consciousness with the consciousness of someone else, whether human, creature, or alien, and also the notion of time being a fluid concept. They were also all page-turners, however unlikely that sounds. And man, they all made me cry. Cool shit is afoot in Australian lit.

What are you reading next?

I don't have this book yet, because it's not out yet, but I'm coveting Elizabeth Hand's Curious Toys, which I've been coveting ever since I heard about it. It's a novel about Henry Darger, and Liz's work is always erudite, elegant, and scathing. I'm also coveting Jeff Ford's Ahab's Return, which is a Moby Dick riff in which Ahab washes up in a Manhattan full of deep story -—Jeff manages to work in language that often seems domesticated but lands in you like a thing with long claws. And ooh, also That Which Girls Conjure Will Help Them Survive, by Kristen Stone. My friend Sarah McCarry's chapbook series Guillotine is impeccable, always, and this novel is about several generations of building a family, and surviving the inheritance of trauma.

August's Post-it note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we’re posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson’s Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here’s her wrap-up and statement from August's posts.

August's theme: Family Vacation

Every summer, every year of my life, we go visit my mom’s family in Idaho. It is all of our time with them crammed into a few days, once a year. I feel frustrated trying to describe it in normal sentences. Lazy days reading or swimming, that calmness—memories of my grandparents, funny stories—relentlessly complex onslaught of family interactions—introvert me with migraines, trouble sleeping—goofing around with cousins, now their children too—epic cooking efforts, my dad baking, my mom’s sudden sewing projects—laughing with my sisters late at night upstairs. Somehow getting ready for bed together as grown-ups creates these last-minute moments that end up being the funniest of the day. Maybe the three of us trying to figure out who got whose boobs was a natural outcome of spending so much of the day in swimsuits, or talking about dead relatives. When I was a teenager, my cousin and I would stay up after everyone else had gone to bed, talking about music, girls, whatever. That year he couldn’t come, he’d just become a father, I missed hanging out, wary of the ways friendships change when people have kids. I’m not sure if we’d ever really talked on the phone until then. Last year another cousin’s daughter was sitting on the couch with me when I casually happened to impart MIND-BLOWING INFORMATION about how size does not indicate age in grown-ups the way it does in kids. Outside there’s always laundry on the line, always shifting, always the same, always makes me think of my grandma. You couldn’t walk past that laundry line without risking her roping you into some task; I think she felt being busy was some kind of protection. The last post-it has something to do with Shelley Duvall—my sister and I had been revisiting old Faerie Tale Theatre episodes from our childhood, I’m kind of obsessed with her singing Harry Nilsson’s “He Needs Me” in the movie Popeye but that seemed to be a memory from my childhood alone, not shared—and something to do with how we always go skinny dipping on the last night. Dark lake, squealing sisters, shocking stars. I get overwhelmed with loving this place, and overwhelmed with the losses it shoves in my face, all the years of my grandma disappearing in front of us until we couldn’t remember her real self anymore, laundry didn’t mean a thing.

The Help Desk: Help me be a better man

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I'm so fed up and mad about this whole bullshit incel thing and so I've decided to read every great feminist book I can find. I know about Backlash, The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique, and all the other biggies, so I'm looking for lesser-known works that will inspire me to understand more and give me language to fight back against my broken gender. Any suggestions?

Henry, Georgetown

Dear Henry,

Personal improvement is a noble goal – I have the organizational instincts of a hoarder but so far have lacked the space and discipline to cultivate them. Good for you for trying.

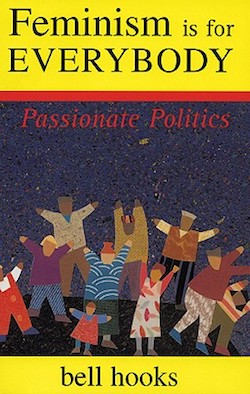

These reads may already be on your radar but they’re some of my favorites: Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist, bell hooks's Feminism is for Everybody, Rebecca Solnit’s Men Explain Things to Me (although I’d recommend just reading the title essay online here and skipping the rest – much of it is overly academic for a general audience. Unless you're ready to dig really deep, pick up Hope in the Dark instead).

And here are a few of my favorite books with strong female leads written by women: Salvage the Bones, Kindred, Americanah, Gilead, Middlemarch.

Because if you really want to better understand women, you don’t need to read the feminist canon, you just need to be a good ally. One way to do this is by choosing to read books written by women and with strong female protagonists – and then recommending those you enjoyed to your male friends. Children are often socialized to regard books with female leads and perspectives as “girl books” and books with male leads as books for everyone, and this sentiment unconsciously carries into adulthood.

Until that changes, or until someone launches angryhorny.com — a dating website exclusively for incels so that women can efficiently detect and avoid them en masse – we are stuck in an imperfect world, one in which I don’t own nearly enough cats to fill up even one garbage bag.

Kisses,

Cienna