Rahawa Haile’s short stories of the day, of the previous week, for November 14, 2015

Every day, friend of the SRoB Rahawa Haile tweets a short story. She gave us permission to collect them every week. She's archiving the entire project on Storify

This week, Rahawa appeared, reading some of her own stories, on the Catapult podcast. You should spend some time there, so that when you read these posts on Saturdays, you'll hear Rahawa's voice when you read her tweets.

Short Story of the Day #308-310

I spent these days recovering. I didn't have it in me to read shorts. I love you, but sometimes I need time.

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 8, 2015Short Story of the Day #311

Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi's "a marriage"

Portland Review (2014)

https://t.co/hy4n2w7Tec pic.twitter.com/kchfscm3fY

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 10, 2015Short Story of the Day #312

Su-Yee Lin's "Westward, Ever Westward"

Okey Panky (2015)

https://t.co/qP56X81Q4L pic.twitter.com/6U4i4GUgrQ

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 11, 2015Short Story of the Day #313

Alexandra Kleeman's "Hylomorphosis"

Conjunctions (2012)

https://t.co/MvKlSnzfmK pic.twitter.com/9DOTzje5mH

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 12, 2015NaNoWriMo Week 3: How to hate writers right

If you're doing your job, and are on target, by Sunday you'll be at a magic place: halfway. Oh my, how good it feels to cross that 25,000 word line. Some of you have already flown past it, so know the feeling.

Some of you probably feel like you'll never reach it and the whole thing is hopeless. It's not. If you've written 10,000 words this whole month, you're 10,000 words into a novel that didn't exist on Halloween. Then, it was a ghost — or worse! The thought of a ghost. Now it has a body.

Don't discount progress, just narrow your focus to what is right in front of you. Look to improve your score every day. That is, if you were to chart the amount of words you write every day, make it a nice upward curve. If yesterday you did 300 words, today do 400. Tomorrow do 500. Make the game smaller than the monthly goal, keep your nose down, and set your sights on lines you can cross with a little effort. Keep moving forward.

Last week I talked about how we feel about our own work while we're writing, but today I'm going to cover something writers don't generally talk about: how we feel about other people's writing.

Yes, of course writers love to talk about writers they're inspired by. We all do. Writers who I love inspire me to work harder. Generally, their influence on me is all dasies and sunshine.

Occasionally you'll see some bromide tossed at Dan Brown on Stephenie Meyer by an established writer; some writers excel at throwing shade, and some love slowly sharpening their knife on the whetstone of other's work, because they know we love conflict.

But of jealousy and green-eyed negativity you will find fewer expressions. Those feelings closer to our base animal self are kept in, and if shared, are done so in close trusted company. Let's change that.

Ten years ago or so, after reading good reviews, I picked up Stephen Elliott's My Girlfriend Comes to the City and Beats Me Up, his fictionalized autobiographical story collection of his sadomasochistic relationships with dominant women. I liked the book, but all throughout I kept telling myself: "I could write this shit better than he is."

Let's weigh that idea. Let's put it on the scale slice by slice: I'm not part of the BDSM scene. I've never had a mistress, or seen a dominatrix. I've never written about sadomasochistic relationships. Surely you can see my scale tipping dangerously towards idiocy?

But there I was, convinced that I could do better. And more than that, I was questioning the fairness of his even being published — and probably selling untold thousands upon thousands upon thousands of novels — when I, such a deserving and talented writer, was undiscovered. Obviously, a situation that sat far outside the fair balance which the world is due to provide me.

I had a story in my head, a story that dealt with some aspects of dominance, submission, and even sadomasochism, and after reading Elliott I decided that I would show the world — I'd show him, dammit — that I had it in me to do better. I would win this by writing, and publishing. Then, all I had to do was lay back as accolades come raining from the sky of my unburdened future, proving me superior.

So I got to work. I wrote that story as hard as I could, a sizable story, 10,000 words. I finished it, showed some people in a writers group. They were underwhelmed. I took the parts of their feedback I felt pointed to things that I could improve, and set to doing just that.

I worked it, and worked it. For years. I wrote and rewrote. I never gave up. I saw in it something each time I found myself dejected. I found a new way to turn it and try it. It went from first person to third, the universe of it expanded, then contracted. No matter what I put in or took out, it came out right about 10,000, like it was destined. I'd pick it up, find a dull spot and polish until it shone. I appraised it from every angle.

I submitted it, and collected rejections. I rewrote it, occasionally from scratch. I workshopped it. I talked about it with kind writer friends who gave unvarnished feedback, some positive, some discouraging. I spent lifetimes inside of its dream. I was sure — absolutely convinced — that it was a puzzle, and as soon as I fit it together in the right way, its beauty and treasure would be apparent to all who encountered it.

But I never did get there. It is still imperfect, in whatever state it has inhabited since my last edit with it a few years ago. I still believe in it to this day. I still think about how to solve it. But I had to make a choice to move on. At some point I put it aside, and worked on my novel.

And in doing so, I looked back at that first passionate encounter with Stephen Elliott's work that sparked the whole thing years before, and I had two thoughts. The first: Stephen Elliott is a much better writer than I was giving him credit for. He was, and is, a better writer than I will ever be. Certainly much more accomplished, and certainly more prolific. Second: I am so grateful to him for writing that book, and for unknowingly allowing all of my negative feelings to ricochet off it.

Because while writing my story, propelled by jealousy and other suspicious and unpleasant feelings, I learned how to write. It was the most intense workshop of my apprenticeship. And that work was funded on the currency of jealousy.

So my advice is very straightforward. Do not indulge in complaining to people how much you hate certain writers. That is like sticking the nozzle in another person's car at the gas pump. Take those negative, horrible feelings, and bring them to your work. Let them motivate you, and propel you. Let them be a punching bag in your workout. Let their color and nuance shape what it is you're trying to say — set your controls for the heart of the hate. Manifest these despicable emotions as trouble for your protagonist. Make them the motivation of your antagonist. Let the gods of your story world wield jealousies that Hera would find a step too far.

This is what artists do. John Donne had it backwards when he talked about "The spider love which transubstantiates all, And can convert manna to gall." We're turning gall to manna here. We're burning dirty coal from our hearts, and watching as it comes out filtered and pure as real human expression.

For of course you should not speak badly of any person ever. It is much better to earn your revenge through the jealousy they will feel when you can present them, smiling, with the manuscript your seething resentment of them helped produce.

The Help Desk: The Tucker Max book club

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I'm friends with a man who claims to ironically love the writings of Tucker Max. He seems like a sweet guy, but is he secretly nursing an inner bro? Should I throw an intervention, and if so, how should I do it?

Nathalie, Crown Hill

Dear Nathalie,

If your friend "ironically" loves the misogynistic writings of Tucker Max, the man known for "jokes" like: "I know this really sexy move you can do with your mouth. It’s called ‘shutting the fuck up,'" he sounds like the kind of guy who'd "ironically" joke that Bill Cosby was being a gentleman by handing out free drinks to women.

Fortunately, there is hope for people who view women as breasty garbage bags to be alternately fucked and despised, and Max himself is proof of that. Perhaps you weren't aware but he's now happily contributing to what your friend might "jokingly" call the pussification of America. His latest book, Mate, Become the Man Women Want was co-written with evolutionary psychologist Dr. Geoffrey Miller. Parts of it are still problematic (for example, in interviews Max compares dating to knowing your enemy before entering into battle). But it's also got some sound advice and when you consider the enthusiastic audience Max has built up with his previous books, his words become especially important:

Objectifying women isn’t just a moral failure. At the purely practical level of attracting women, it’s stupid. It might temporarily reduce your anxiety about approaching them (about making your pitch), because if you think of them as targets, you can try to trick yourself into thinking that they won’t be judging you when you walk up to them. But they are judging you—and that’s OK, as long as you understand how and why.

Here's the intervention I suggest: Buy Max's latest book, read it, and then give it to your friend. Tell him that you're really eager to discuss it with him and get his thoughts on Max's evolving views on women and relationships. (Also make note of the parts of Max's book that you disagree with and be ready to explain these parts to your friend.)

If your friend is resistant, join our nation's great underground army of literate feminists and their decades-long campaign to sissify our great nation: pull a Cosby and start dosing his drinks with birth control pills. I'm not a doctor – although I'm considering legally changing my first name to "doctor" for the free respect and travel upgrades – but the extra estrogen will probably help. I spent years throwing birth control pills in the open reservoir at Volunteer Park and I'm pretty sure it turned at least a few gay men I know even gayer.

Kisses,

Cienna

PS. Happy World Vasectomy Day, everyone!

This "Introvert" Christmas ornament from Archie McPhee, featuring a bespectacled reader hiding behind a book, seems like the sort of thing that readers of this site might enjoy. (They're not a bookstore, but the Seattle Review of Books still loves the ever-loving hell out of Archie McPhee.)

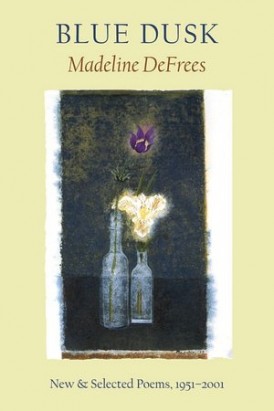

Madeline DeFrees, 1919 - 2015

Very sad news: we've received word from her literary executor that Madeline DeFrees, a Seattle poet, passed away last night. She would have been 96 years old next week.

DeFrees was widely celebrated, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in Poetry and two Washington State Book Awards. Her most recent collections were published with Copper Canyon Press. According to her website, DeFrees "spent 38 years as a nun with the Catholic Congregation of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. She entered the community after high school and later requested release because, in her words, 'religious life and poetry both demand an absolute commitment.'"

DeFrees's work demonstrates an unflinching honesty that could make many self-styled confesssional poets blush, but it never feels clumsy or leering or unwelcome. Her charge as a poet, it seems, was to capture the workings of her mind, with all its contradictions and inconsistencies, and relate it in beautiful, entrancing language. DeFrees was absolutely right; poetry demands "an absolute commitment," and she gave nothing less.

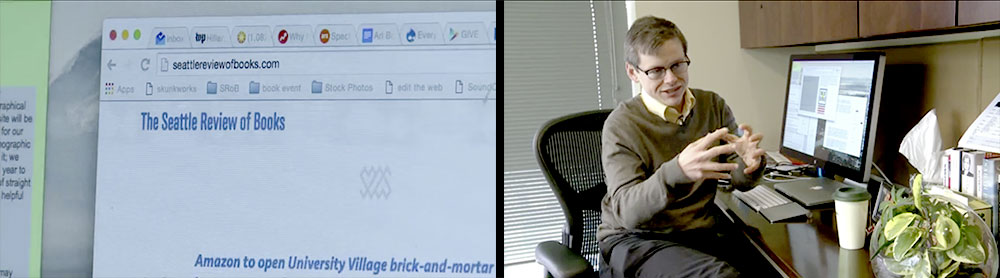

If you were watching NBC News last week you have may have noticed a segment about the Amazon bookstore opening in Seattle. In that clip, you may have seen our own Paul Constant giving his (our, really) opinion on the matter.

But we didn’t know until today (despite nice friends letting us know) that the video played on national NBC News, not just King5. Today we uncovered the video in question, and are offering it for you here, in the least timely way possible, so that you, like us, can cheer when you see our website appear on that master of all media, big television. Or hiss, if you're a hate reader (welcome to the site!).

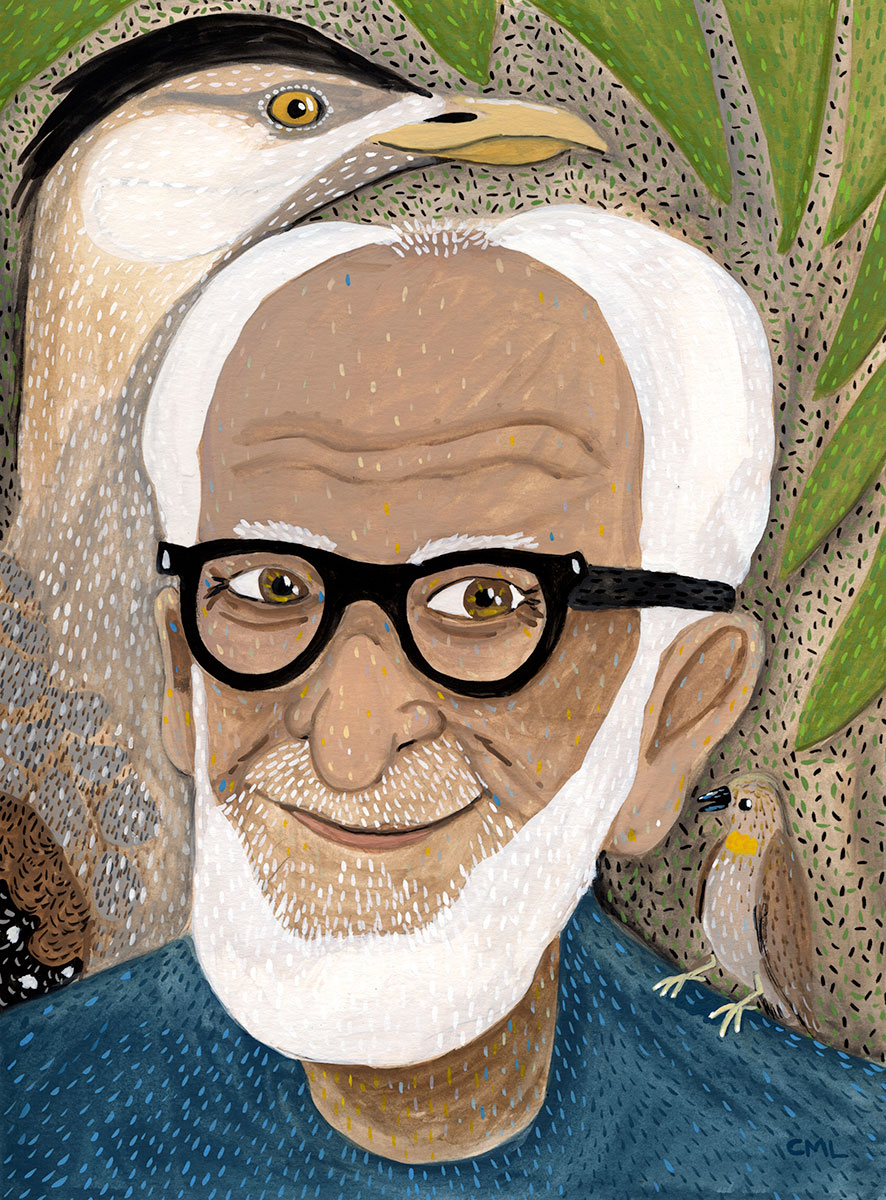

Portrait Gallery: Salim Ali

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Salim Ali was an Indian ornithologist and naturalist. His 1941 book The Book of Indian Birds went through at least fourteen editions. He won the second J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation prize, from the World Wildlife Fund in 1975. Ali died in 1987 at the age of 90. Today is his birthday.

Kara Brown's interview with Johari Osayi Idusuyi, the woman who read Citizen at a Trump rally and thereby became an instant celebrity, wins the internet today. Just perfect.

Living up to the best

Published November 12, 2015, at 12:29pm

Jonathan Lethem's Best American Comics 2015 might not be the best comics anthology out there, but it is certainly the best comics anthology edited by Jonathan Lethem this year.

This morning, the APRIL Festival announced something fun: their first-ever writing contest! And the Seattle Review of Books is coming along for the ride:

The APRIL 2016 contest is simple: submit a written piece of any genre or form, 400–500 words in length, before the December 12 deadline. The APRIL team will select five finalists, with the winner to be selected by The Seattle Review of Books. The winning piece will be published on The Seattle Review of Books and performed during the APRIL 2016 festival and the winning author will be awarded a $100 honorarium. Please note that this contest is limited to those individuals who have NOT read at an APRIL event before.

There's no fee to enter, so send your best stuff along. We're very much looking forward to reading your work, and to publishing your work, and to attending your reading. Read all the details here.

World Fantasy Award organizers recently announced that they would stop giving out busts of infamous racist H.P. Lovecraft to winners. Lovecraft biographer S.T. Joshi is outraged, calling the decision “a craven yielding to the worst sort of political correctness.” Joshi has returned his World Fantasy Awards in protest, The Guardian reports.

It's important to draw a distinction between banning the works of Lovecraft — which nobody is demanding, for the record — and literally idolizing him with a statue. Much has been written about Lovecraft's racism in recent years, including the Lovecraft-inspired comics of Alan Moore. Here's an interesting essay about Moore's evolving attempts to address the racism in Lovecraft's work. We can't sweep that part of Lovecraft's character under the rug; we must acknowledge it, examine it, and learn what we can from it.

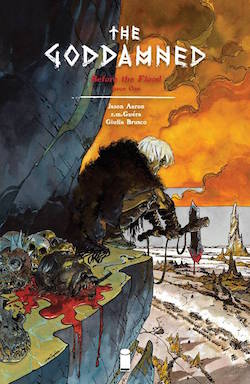

Thursday Comics Hangover: The preacher's curse

The nerd internet got very excited a few weeks ago when the first trailer for the Preacher TV series was posted to YouTube. The trailer, to me, looked like a lot of hand-waving with very little substance, but then I’ve got conflicted feelings about Preacher. When I was a teenager, it was my favorite comic, a huge epic story — let’s be honest, a superhero story — about good and evil and, most importantly, sacrilege.

I haven’t read Preacher in years, in part because I fear it has probably aged very badly. Even though it launched in the mid-90s, Preacher likely now reads like something from a long-ago era, since it's packed with gay panic jokes and sexism. Those were never the appeal for me; I was there for the fun of a comic which casts the Christian depiction of God as the villain. For a lifelong atheist, it was a real thrill. Maybe Preacher’s transgressive nature meant that it would never age well. It’s impossible, after all, to be permanently transgressive; if you seek to offend, shifting cultural norms mean that you will most likely not be able to offend the next generation — at least in the way you originally intended.

The book begins “1600 years after Eden,” with a nameless figure waking up after being brutally assaulted. He then wanders the desert, completely naked, in search of the people — or, in this case, the giants — who beat him up. Captions deliver his narration to us: “I have walked this pile of shit we call a world for 1600 years. I have cursed God every way he can be cursed, including to his face.”

We eventually do discover our protagonist’s name, and it reveals him as a famous Biblical figure. At the end of the book, we’re introduced to an antagonist who also is a Biblical figure. The pacing, with the villain identifying himself on the very last page, is very much of a superhero comic, but The Goddamned seems desperate to label itself for mature readers. It’s got bad language and nudity and violence and, I guess, “adult subject matter.”

The Goddamned didn’t work for me, in part because I felt as though its edgy Bible riff might age as poorly as Preacher has. How many different ways can comics writers ostentatiously raise their middle fingers to the heavens? The first issue of The Goddamned is all attitude and posing, with no real sign that there’s anything substantial happening in the background. Maybe future issues will pay out in surprising ways. That’s entirely possible; Aaron certainly has the capacity to tell a good story.

If there’s a reason to pick up The Goddamned, it’s Guéra’s art. This is the kind of hyperdetailed style that Americans used to describe, with a certain kind of longing, as “European.” A double-page spread of the marauding giant hordes is so full of debauchery and sin that it’s like a Where’s Waldo of monstrosity. During the eight-page, mostly silent fight scene in the middle of the book, (another reminder of superhero comics) Guéra ilustrates violent acts with economy and gravity; you can always tell what’s going on in every panel, and he doesn’t allow the action to overwhelm the page. He keeps the panel count high, rather than blowing the fight scene out into a too-extravagant series of splash pages. His art, it must be said, is almost too good for the comic in which it appears.

Yesterday, the APRIL Festival announced that Jenny Zhang will be the writer-in-residence of their next festival, which will take place the week of March 15—20, 2016. Zhang is the author, most recently, of the poetry collection Dear Jenny, We Are All Find. Unfamiliar with her work? Try this piece, which she published with Poetry magazine:

When someone dies, we go searching for poetry. When a new chapter of life starts or ends — graduations, weddings, inaugurations, funerals — we insist on poetry. The occasion for poetry is always a grand one, leaving us little people with our little lives bereft of elegies and love poems.

But I want elegies while I’m still alive, I want rhapsodies though I’ve never seen Mount Olympus. I want ballads, I want ugly, grating sounds, I want repetition, I want white space, I want juxtaposition and metaphor and meditation and ALL CAPS and erasure and blank verse and sonnets and even center-aligned italicized poems that rhyme, and most of all — feelings.

She has also written extensively for the wonderful Rookie magazine. You'll have plenty of opportunities to get acquainted with Zhang's work this spring; the writer-in-residence at APRIL participates in a number of readings and also writes about the festival as it happens. It's a great way to get a writer acquainted with Seattle, and vice versa.

Katherine Miller at BuzzFeed has compiled a fun, uh, gifsticle(!?) about the woman who very publicly read Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, a book which "investigates the ways in which racism pervades daily American social and cultural life, rendering certain of its citizens politically invisible," at a Donald Trump rally. The thing is, Miller's article didn't cover the best part: the angry white man who tried to get the woman to stop reading and pay attention to Donald Trump, who was, at that exact moment, talking about how much sleep he gets every night. You should watch that whole interaction play out here.

Part of the mission statement for the Seattle Review of Books is to keep the art of the book review alive for another generation. Too many review outlets subscribe to the notion that a book review is just a plot synopsis with a little bit of thumbs-up or thumbs-down commentary stapled onto the end. We think book reviews are unique pieces of art; they are criticism written in the form they're critiquing. This opens up all sorts of neat opportunities. We believe that the best days for book reviews are ahead of us.

And there's a place for you in that future. SRoB co-founder Martin McClellan and I are teaching a class on book reviewing at Hugo House in January, and we'd like you to attend. It's called "The You Review of Books," and here's a synopsis:

Do book reviews matter in the age of GoodReads and Amazon customer reviews? The Seattle Review of Books co-founders Paul Constant and Martin McClellan think so: they say book reviews should be beautiful pieces of writing in response to beautiful pieces of writing. They’ll explore what makes a great review by providing examples and plenty of exercises and advice for how to read, think about, and write compelling, engaging, and intelligent reviews. Their goal is nothing less than training future writers for their website and inspiring writing about books everywhere in the world.

Hugo House members can sign up for the class starting on December 1st. Non-members can sign up starting December 8th. We hope to make this an entertaining class about the theory and practice of book reviewing, which is to say we hope to help you become a better reader, a better writer, and a better critic. We also hope to recruit future SRoB reviewers out of the class. If you have any questions, please feel free to send us an email. We'll post a reminder here on the site as soon as the class opens to the public.

The bookshelves where science and humanities meet

John Paul DeGennaro started working at Ada’s Technical Books about a year and a half ago. He had just moved back to Seattle after graduating from the University of New Hampshire as an anthropology major. He says he’d never worked in a bookstore before, though he’d always wanted to, because it appealed to his interests in science and education.

Earlier this month, DeGennaro became Ada’s new events coordinator. So what does he think makes for a great event? “We like to put on events that are learning-based. We’ve done some literary events that are great, too, but we like people to leave feeling like they’ve gained an understanding of something new.”

And what are some upcoming events that he’s looking forward to? “Thursday we have an event on the impacts of climate change on marine systems with UW professor Curtis Deutsch” to talk about increasing oceanic acidification and rising sea temperatures. And on December 10th, Ada’s will host an event by Dr. Travis Rector, author of the book Coloring the Universe, about how NASA produces such gorgeous color photographs of nebulae half a galaxy away. How do they gather such an impressive slate of oceanographers and astronomers? DeGennaro says that until now, authors have reached out to the store looking to put on events, but he’d like to be a little more proactive and “scout out some people” to put a bigger slate of readings together, too.

DeGennaro also hosts Ada’s Human Experience Book Club, a monthly “survey of non-fiction books exploring what it is like to be human.” This month’s selection is Being Wrong by Kathryn Schulz, which is about “why we think we’re right all the time even though we’re not, and why it’s important to make mistakes, and why mistakes help us both in life and as a species.” DeGennaro says he likes to use book clubs “as an introduction to a topic to then explore different ideas and hash them out in discussion context.” For instance, he says, “we read Spook by Mary Roach a couple months ago. We talked about the book, but then we used it as a way to talk about death in our culture. I like to use book clubs as an excuse to talk about broader topics.”

In the end, what drew DeGennaro to bookselling was the idea of understanding the world. He believes that “we have a problem right now in our culture where we try to separate things into as many small categories as possible,” and that we should “blend the humanities and arts and sciences back together, because they’re kind of separated right now.” This makes a place like Ada’s, where biographies and technical scientific texts and the work of Philip K. Dick share space a couple feet away from a bustling cafe, a perfect landing spot for him, a welcome intersection between science and art and the humanities.

From Jessica Roy at The Cut, a horrific lede:

A British man used social media to stalk a teen in Scotland, then traveled 500 miles to the grocery store where she worked and smashed her over the head with a wine bottle, all because she gave his self-published book a bad review.

Maybe it's time to briefly go over the rules of engagement for authors?

- Be gracious and brief when you receive praise on social media.

- Engage with your fans. Be nice and kind and good.

- Never respond to critics who write bad reviews; you're not going to convince a critic that they actually liked your book, and bystanders will think you're petty.

- Don't stalk your critics and hit them with wine bottles. In fact, don't hit them at all. Or stalk them. Don't stalk anybody. Don't hit anybody. Don't be a bad person. Be a good person.

- Rule 4 is the most important one.

Drink to forget, ink to remember

Published November 10, 2015, at 11:45am

The important thing about Tatiana Gill's comics is that they're unfailingly honest, whether she's talking about drinking or sobriety or a bad Facebook habit. If you're sick of phony narratives imposed on top of memoirs, maybe Gill's comics are the cure you didn't know you needed.

All of Us, Whatever We Are

Remember the time you watched your uncle

prepare to enter the woods to hunt? The uncle

hunted with a bow and arrow, he greased

his boots for waterproofing, he wore

a brilliant poppy for a hat. You did not go

to see the breath billow from the mouth

of the uncle past the brush of the brown moustache,

or pause when he paused, knee raised, knuckles

loose, ears prickling. You stayed at home

and hoped for the deer and the uncle to miss

each other, to dance in different parts of the woods,

you didn't know how hunting worked. You imagined

saltlicks and deerblinds and crooks of trees

and cracks of branches. It was all out of books.

The books fell down around them, man and animal,

a flush of russet leaves, and landed without sound.

You went on turning pages, and they went on

stepping silently, and the arrow waited, eager

for the string to touch its lip, for the air to dare

to bite. In you and in the deer and in the uncle

the hot blood ran after its own scents, trailed

by its own pursuers, the hearts made their fists

and opened their mouths over and over.

In the uncle's hand, the arrow felt

indifference, as the knives and bullets

and needles and steering columns all feel

indifference. We are dry, now we are wet.

It is warm, but it will soon be cold, the body,

the blood, the idea of you hovering there

as the last of the life leaks away. Where

does the warmth go? We try to track it down,

to find it lurking in the dark trees, coax it

into sunpools, hope it stares at us

with enormous eyes. We want to touch

its little feet, to turn the soft tongue from side

to side. We move through snow and bear up

under wind. We blink the frost from the lashes,

we flex the thumb going numb in the chill. We want

the beating thing that lies beyond the reach

of our barbed touch. We want chance to spin

the dial, we want the arrow to thread

the gnarled trunks and hit the heat in the heart —We run to it, bracken snapping, shouts

of wonder in the ringing air. We hold the heat

a moment, its muzzle wet, and then we feel it

moving off, a shuffling shadow with no edges

cast by a cloud that is not there. And you look up

and the uncle looks up too and the deer

with its amber iris stares along with you

and everyone sees sky and endless space

and the unstoppable cold comes dropping.