The Triangle Factory Fire of 1911, documented in verse

Our sponsor this week, Donald Kentop, became fascinated with the Triangle Factory Fire, after learning that the building where the tragedy happened still stands as the Asch Building. It's part of New York University, and Kentop had classes in the building when he was a student.

He has woven a deep history of the fire, told in verse, through the stories of survivors, victims, and the unfolding of the event itself, in his book Frozen by Fire. The book, full of images and portraits, is a rich portrait of a tragedy the shaped American life.

Kentop will be appearing Sunday, November 15th to read from the work, at the Seattle Public Library's Ballard Branch.

Like Kentop, you can join with us to make internet advertising 100 percent less terrible. We're breaking the mold and trying to create something new that benefits both us, and you, the reader. Reach our readers with your work, and together let's make advertising something we look forward to.

The algorithm method

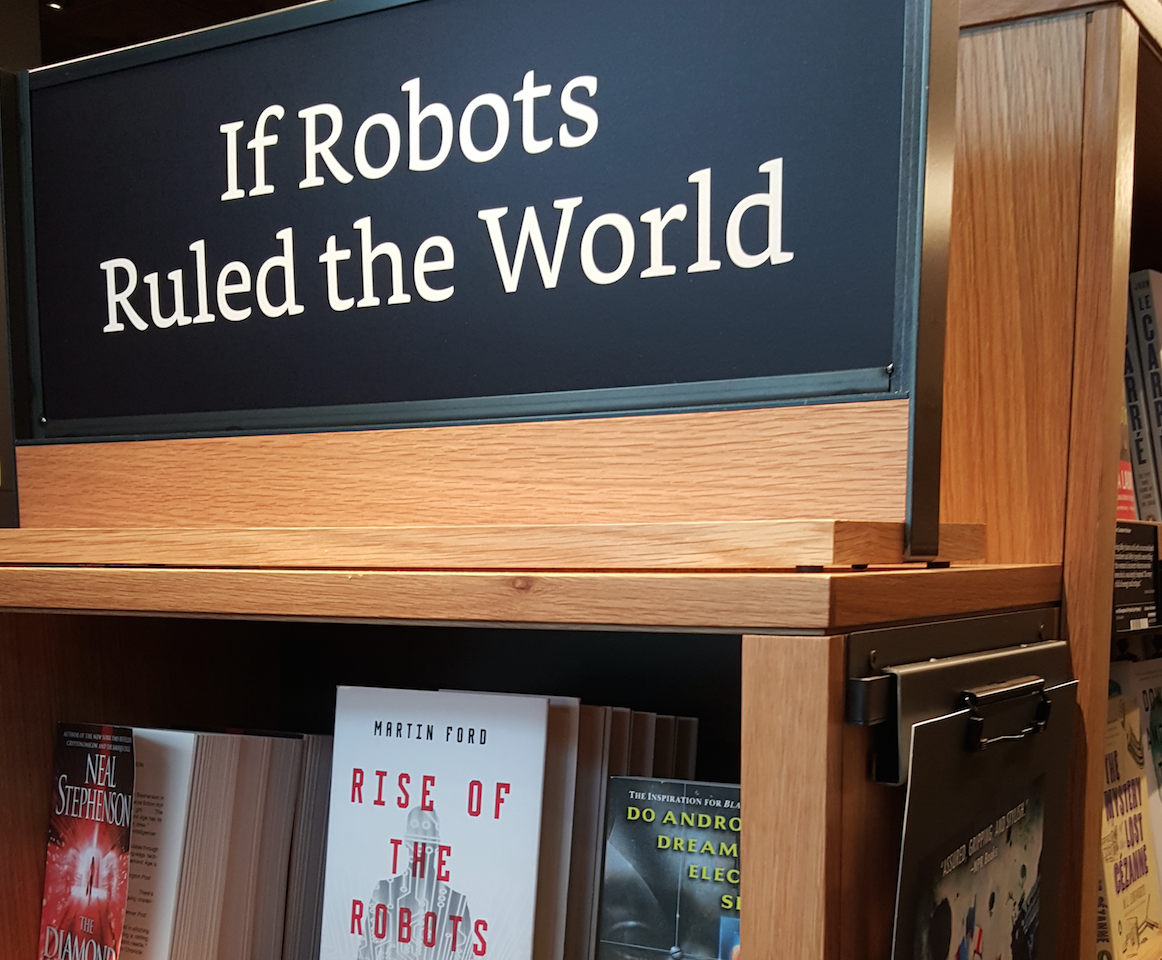

Amazon.com has come a long way. They’ve been in business for two decades now, moving billions of dollars of merchandise around the world, harvesting untold amounts of information from their customer transactions and searches, collecting tens of billions of pages worth of customer reviews on products, and investing tens of millions of employee work-hours into tightening the gap between customer desire and customer satisfaction. In many ways, the culmination of what Amazon sought to do with all that data is now made physical, in the form of a brick-and-mortar store, Amazon Books, in a University Village storefront formerly occupied by a conveyer-belt sushi restaurant.

Amazon Books is presumably intended as a showroom for Amazon.com, a physical manifestation of everything Amazon’s founders believe, and a destination for Amazon’s most enthusiastic fans. If corporations can feel pride — and why not? they’re people, after all — Amazon Books thrums with a glowing sense of corporate self-regard. This is a brand that is singing a song of itself.

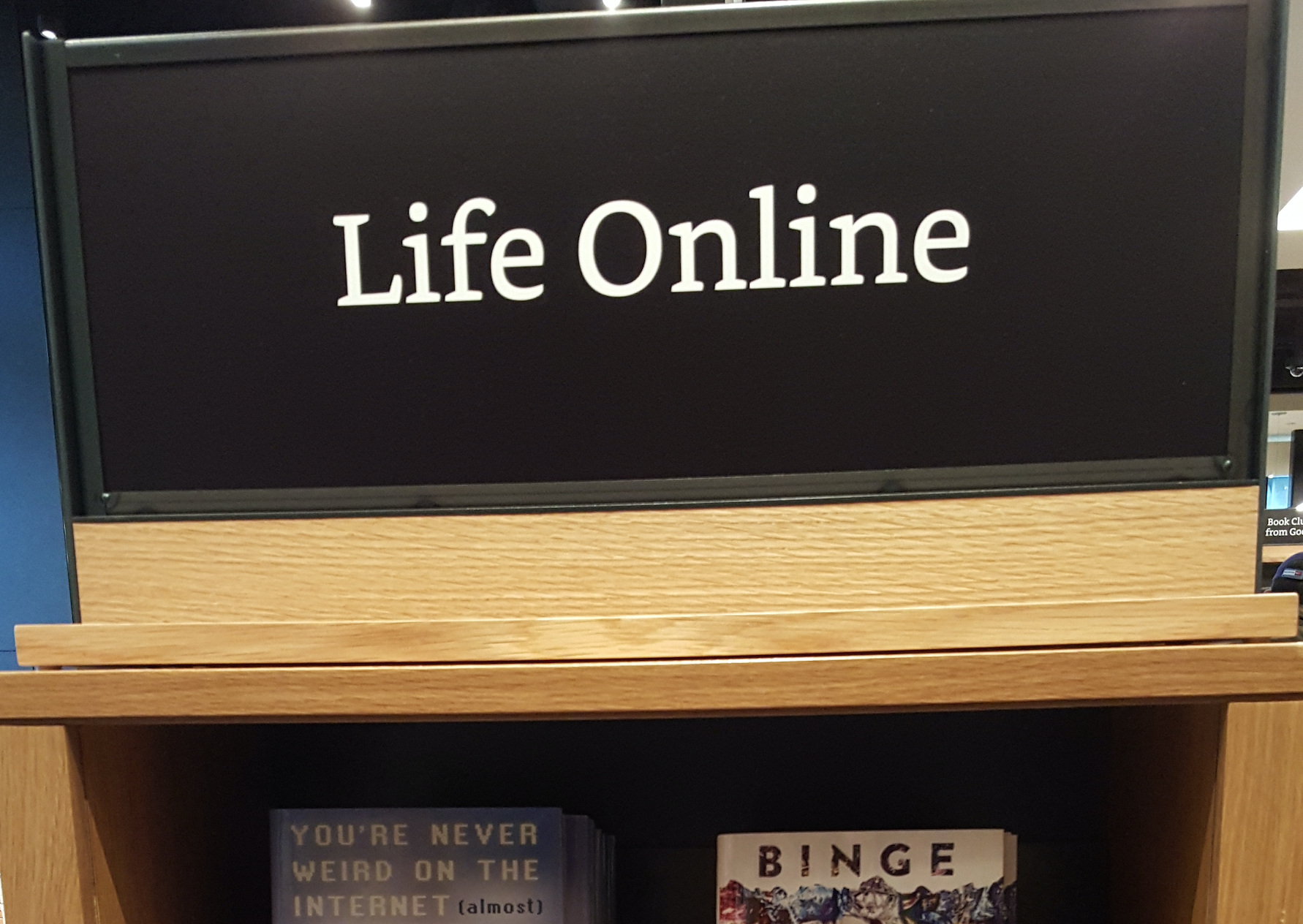

Every inch of Amazon Books is a promotion for Amazon.com, a meatspace billboard for a virtual experience. The speakers play inoffensive jazz that signs helpfully inform you can be found on Amazon Prime Music. Books are priced, other signs crow, the same as they are on Amazon.com. The center row of the store is handed over to Amazon’s physical products — the cylindrical, always-listening Echo; the colorful Fire tablets for children; the generic Bluetooth speakers; the television streaming boxes. But aside from a tablet here or there, the rest of the store is devoted to books. The vast majority of the books are faced-out on shelves, with a few endcap displays and a couple front table of new releases.

Spend five minutes in Amazon Books and you will likely describe it as a fairly typical corporate bookstore experience, a cleaner and more enthusiastic Barnes & Noble. But spend a little more time in Amazon Books — an hour say, on a Saturday morning — and you’ll realize the true achievement of what Amazon has done. All that data, all those national GDPs worth of products shipped, all of that has built to this moment, this destination, this apex. What Amazon has built in Amazon Books is nothing less than the world’s greatest airport bookstore.

Let’s talk about what bookstores do. Before I became a book reviewer, I spent more than a decade working in bookstores: at Elliott Bay Book Company, and at Borders, and briefly at the Brattle Bookshop in Boston. And part of the reason why the transition from bookseller to book reviewer was so easy for me is that they are, at root, the same job.

A bookseller’s job, and a book critic’s job, is to introduce books to the universe, to start the conversation between book and reader. If you think of a book as a concentrated chunk of thought and empathy and human experience, it’s in bookstores and in book reviews when they start to effervesce, and fizz, and the ideas start to spread into the atmosphere, where we breathe them in. It’s a bookseller’s job to make sure that the right book gets to the right person at the right time.

Sometimes, a bookseller will slyly sneak a subversive young adult novel into the hands of a teenager right in front of their parents — the kind of book that will alter the course of a life, handed off in a seemingly banal retail transaction. I don’t need to tell you the power of books; they can rewire brains, drop whole memories and emotions into our life story that wouldn’t have existed otherwise, and they can, more than any other medium, get us inside the heads of other human beings. They make us less solitary creatures. Every bookstore, then, has tens of thousands of conversations inside of it, waiting to be unleashed into the world.

Those conversations are on the shelves at Amazon Books, too. You can find titles by Ben Marcus and Gwendolyn Brooks and David Foster Wallace and Marilynne Robinson there. Part of the reason Jeff Bezos decided to use books to launch his online retailer was the fact that books are remarkably sturdy units. Every copy of The Scarlet Letter in a single print run is exactly like every other copy. You don’t have to worry about different sizes that have to be returned and re-shipped after a customer tries them on. You don’t have to worry about a book going bad after it passes its expiration date. So a David Foster Wallace book you buy at Amazon Books is the exact same book you’d buy at University Book Store. These books have the same power as any other books in any other bookstore in all the world. The problem is the way Amazon Books directs the conversation around those books.

Everybody knows by now that ads and retail sites online are directed toward individuals. Your Amazon buyer history means that you have a different Amazon homepage than me, and your Facebook ads promote different products than mine. The great failing of Amazon Books is that it can’t reconfigure itself for every customer who walks through the door. You’re not welcomed with a different set of front tables than I am; it’s the same selection, with Scott Pilgrim and the new Donald Trump book, for everyone.

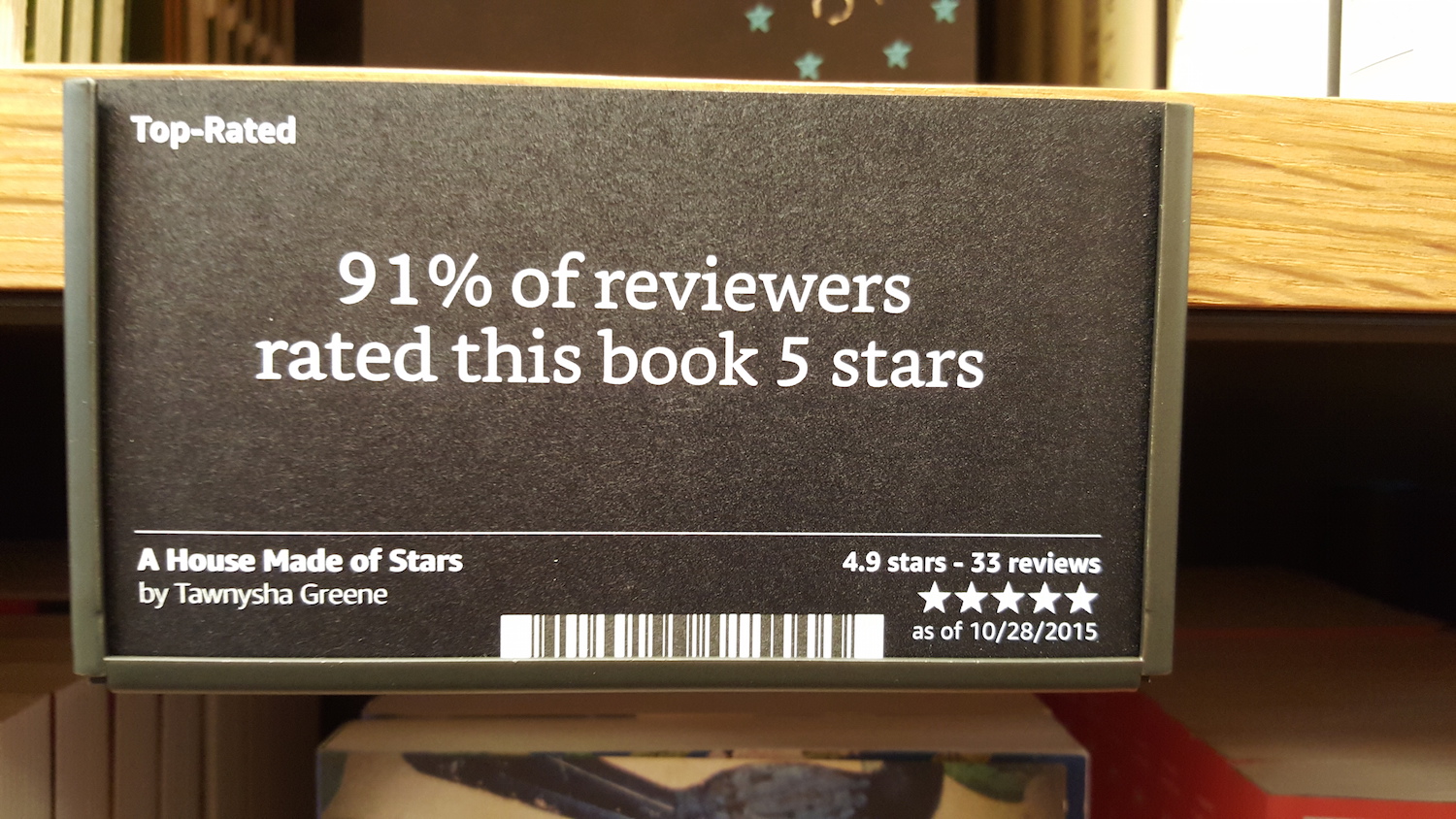

So since the current demands of time and space demand that Amazon can’t suit their bookstore to match the need of each individual customer, they had to compromise. Instead, they decided to please everyone. The way Amazon did this was through a method that an Amazon spokesperson infamously described as “data with heart.”

So what does “data with heart” mean, exactly? It means you get a bunch of awkward signs on endcaps promoting books with signs like this: “Highly Rated Business Books 4.7 Stars & Above.” Okay. That sure is specific. But what does that mean? How many people rated Paul Downs’s Boss Life 4.7 stars or above? Why did they rate it 4.7 stars or above? What would it mean if Boss Life was rated 4 stars? And how do books on that display compare to the books on the next display over, which a sign informs us is made up of “Business Top Sellers,” which are rated “4.5 Stars & Above?” Does that .2 star matter? Why or why not? What are you trying to tell us, besides the fact that these books are popular, and that people who rated them rated them highly? How does a 5-star rating for Getting to Yes relate to a 5-star rating for the Bible? You might give Purity 5 stars, and I might give The Complete Poems of Denise Levertov 5 stars. Maybe I’d give Purity 2 stars and you’d give Levertov 2 stars. Why, really, should anyone care? It's what you do with the book, what you learn from the book, and what you share from the book with the world that truly matters.

Supposedly, the aggregate is how Amazon defines the quality of a book. Many of us have gotten into fights on Facebook about a movie — Jurassic World, say. We know how those fights go. We’ve argued that the movie was dumb and bad but the other person replied, “well, it’s rated 92 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, so I guess someone must agree with me." As though an aggregate of critic scores is as immutable as, say, the speed of light, or freezing temperature, or the melting point of steel.

It’s just not that simple. If 500 people rate a book 5 stars and I read the book and hate it, that doesn’t make my opinion any less meaningful than theirs. It means I entered into a conversation with the art and I had a different conversation than those people. It doesn’t allow for the individual human experience, because it’s too busy condensing hundreds or thousands or dozens or however many experiences into five narrow lanes.

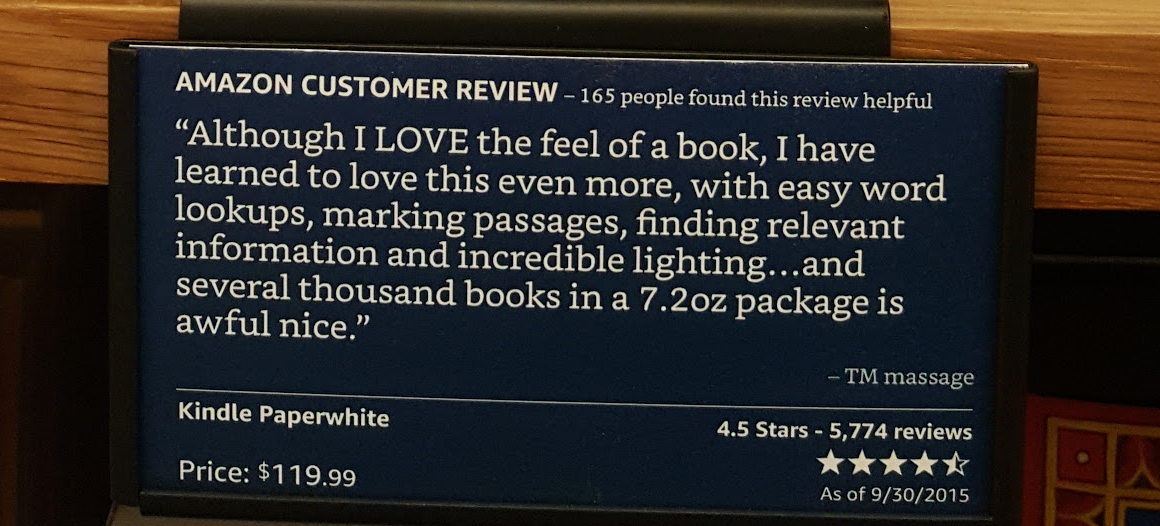

Imagine a restaurant that included Yelp reviews of specific dishes on its menu and you get an idea of Amazon Books. One recommendation card by an Amazon user named “scot16897” — there’s no sign whether Mr. 16897 consented to have his review printed, but that’s probably part of the boilerplate user agreement when you sign up for Amazon — praises a book by saying “Not only is the story good, but there are so many small jokes and references, I found myself literally stifling laughs while reading in public.” So, Mr. 16897, what makes a story “good?” Why is a story bad? What makes you laugh? Why should I suddenly care what an anonymous person on the internet has to say, just because his comment is printed on a card and slapped on a bookshelf?

Most aisles of Amazon Books feature Kindles loaded with samples of the books on the shelves of that particular aisle. It’s a weird choice. Why would you push a bunch of buttons on a Kindle to summon up a sample of a book that already exists on a shelf right in front of you? Why wouldn’t you just pick up the book and start reading it?

The experience only served to remind me that e-readers now feel hopelessly outdated. I hadn’t held an e-reader in a long time, but the slow flashing of e-ink as I swirled through a menu felt like an old-timey experience. Even though the recommend card for the Kindle, written by one “TM massage,” assured me that they have “learned to love” the Kindle “even more” than “the feel of a book,” I felt like I was poking around on a manual typewriter. I say this as someone who bought an e-reader—a Sony Reader — years ago, when e-books seemed to be an inevitability. At the time, I thought reading on the device was fine, perfectly acceptable.

Now, even though the Kindle Paperwhite is supposedly Amazon’s top-of-the-line e-reader, it felt silly and awkward, a rickety reminder of a moment in 2007 when a man, high on internet hubris, actually believed he could render the book obsolete. I looked up from the soggy grey text of the Kindle, and blinked, and looked around at the bookstore, at all the kids poking at the tablets mounted in the childrens’ section, and thought to myself that everything eventually looks old and stupid and slow. Except books.

The final problem with Amazon Books is a curious one. Amazon.com made its name, in part, by having the biggest selection of books in the world. Their physical bookstore boasts a wide array of bestsellers, recent award-winners, and a few representative examples of classics. In comparison with the online retailer, Amazon Books is home to a remarkably shallow assortment. It’s like looking out at a lake that stretches almost to the horizon, stepping inside, and discovering that it’s a crystalline puddle, no more than a quarter-inch at its deepest part.

The poetry section of Amazon Books takes up a single bookcase. It has 26 titles in it, all faced out in even little stacks on four shelves. I left Amazon Books and walked a few miles to Third Place Books Ravenna, headed to the back of the store, and faced their poetry section, which took up two bookcases—15 shelves total. Every single one of those shelves had more titles on it than the entirety of Amazon Books’s poetry section.

I started counting. Third Place Books Ravenna had 758 poetry titles in its poetry section, the size of almost 30 Amazon Books poetry sections. Shelf tags in the section handwritten by store employees, people I could find and talk to in the store, directed me toward specific titles. A pair of display shelves faced out certain books that the employees liked. Nowhere did I see any statistics, or arbitrary 5-star ratings. It was a wall full of conversations, ready to launch out into the world. I breathed a sigh of relief. I was home.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from November 9th - 15th

MONDAY Garth Risk Hallberg reads from his enormous, buzzy debut novel City on Fire at Elliott Bay Book Company. I haven’t read this one yet — every season seemingly brings with it a Big Ambitious Novel By a Young White Guy, and it’s very hard to tell which of them really matter. (The last one of these big novels, Joshua Cohen’s The Book of Numbers, was widely celebrated as a success on its release this spring, but most people I know who’ve read it call it a bust.) Everybody’s talking about Fire for its depiction of New York City in the 1970s, which is at least promising; if a writer can successfully write about a city, they’re probably worth your time.

TUESDAY University Book Store hosts an event sponsored by the Science Fiction Writers of America. Authors Jason Hough, Stina Leicht, and Adam Rakunas will read and talk about writing science fiction. Hough is the author of the The Dire Earth Cycle of books, Leicht's “flintlock fantasy” is titled Cold Iron, and Rakunas is the recently transplanted-to-Seattle author of the novel Windswept, which I reviewed in September. It’s always fun to see sci-fi authors get together and talk shop; they’re usually a little more open than their literary fiction cousins when it comes to the art and business of writing.

WEDNESDAY It’s Veterans Day, and so the Red Badge Project presents a reading of new work by women veterans at Hugo House. Seattle authors Suzanne Morrison and Sonya Lea present new work by women who have served in the military, many of whom have experienced trauma. The Facebook invitation for this event calls this “an opportunity for the public to hear the experiences of women veterans, and in so doing, become a part of a community ceremony to witness who they were, and who they are becoming.” Sounds like a fitting way to spend your Veterans Day.

THURSDAY At Town Hall Seattle, it’s a live edition of Ampersand magazine, with special guests including KEXP DJ John (of “…in the Morning” renown) Richards, artist and childrens’ book author Nikki McClure, poet Janie Miller, and many others. The organization that puts this event on, Forterra, “works to conserve the environment and build communities throughout the Northwest.”

FRIDAY Okay, so the event everyone is going to be talking about is Jesse Eisenberg and Sherman Alexie at Broadway Performance Hall. Obviously, this will be a good time. Alexie is a brilliant reader and a very good interrogator. Eisenberg is a marvelous actor. But this event is also going to be packed — it’s a free event and so it’s first-come, first-serve — and it will likely be as “sold out” as a free event can get. We try not to promote sold-out events in this column. So we’d like to suggest you head to the Youngstown Cultural Arts Center in West Seattle for a reading from wonderful poet and novelist Karen Finneyfrock and poet Roberto Ascalon. Finneyfrock will read from her still-in-progress book The Year We Ruined the House. Ascalon will read some of his incredible poetry.

SUNDAY You might as well camp out in the Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery all weekend long, because today, Jonathan Lethem presents the Best American Comics 2015, which he edited. Lethem, obviously, is one of the finest novelists alive, and he’s also a wonderful fan. He’s written adoring, brilliant pieces about comics that he loves, authors he adores, and music that he can’t live without. He also wrote an excellent book about the movie They Live. Lethem is likely to be a huge geek this afternoon; this is a good thing, because nobody geeks out better.

The Sunday Post for November 8, 2015

The Fort of Young Saplings

Settle in, folks. This one will take a bit of your time, but I promise you won't regret it. Oregon (and ex-Seattle) writer Vanessa Veselka goes deep on her personal connection to a clan of Tlingit people in Alaska, and using that connection explores the history, legends, and relationships with Russians, of this Alaskan indigenous people. A stunning piece of writing.

The Tlingit don’t fit stereotypes of Native Americans. They’re more like Vikings. Or maybe they’re more like Maori. A fiercely martial people, terrifying in their samurai-like slat armor, their bird-beak helmets, and their raven masks, they never surrendered to a colonial power, never ceded territory. When Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Tlingit argued that the Russians held only trading posts and that the rest was not theirs to sell. The protest was unsuccessful, but it was the beginning of a narrative: The Tlingit had never signed away their land, had never sold it, had never moved.

The Decay of Twitter

I hate pontificating about Twitter as much as the next person (Twitter is the ultimate expression of the parable about the blind men and the elephant, except the blind men are 320 million men and women, and the elephant is just an idea), but this piece is pretty good, and has some good points about Twitter the network that people have feelings about, and Twitter the company that is trying to make a go out of it.

Since it went public two years ago, investors have rarely considered Twitter’s prospects rosy. The sliver of Twitter’s users who are interested in how it fares as a corporation have gotten used to this, I think: There’s an idea you see floating around that, beyond avoiding bankruptcy, Twitter’s financial success has little bearing on its social utility. Maybe there are only 320 million humans interested in seeing 140-character updates from their friends every day after all. If you make a website that 4 percent of the world’s population finds interesting enough to peek at every month, you shouldn’t exactly feel embarrassed.

Long Line at the Library? It’s Story Time Again

All about story time at the New York Public Libraries:

Among parents of the under-5 set, spots for story time have become as coveted as seats for a hot Broadway show like “Hamilton.” Lines stretch down the block at some branches, with tickets given out on a first-come-first-served basis because there is not enough room to accommodate all of the children who show up.

'The Good is Elusive and Transitory in This World'

Jessica Gross spends some time with the impossibly wonderful Maira Kalman (and even sat in her Eames Le Chaise chair)

I always told my kids, don’t have serious conversations with your mates at night, because everything looks so dark you’re going to have a fight in two seconds. Just don’t do it. I always say, “If you’re hungry you should eat something, and if you’re thirsty you should drink something, and if you’re tired, you should sleep.” They’re always making fun of me for saying that, but I think there are some truisms that are very, very basic. And if you just listen to what you need, sometimes it will take you out of troubling spots.

Does Fiction Based on Fact Have a Responsibility to the Truth?

Thomas Mallon and Ayana Mathis tackle this question in the Times. This from Mathis' piece:

At the risk of stating the obvious, truth and fact are not the same things. Our belief in the truthfulness of facts is mutable. I recently saw Joshua Oppenheimer’s superb documentary, “The Act of Killing,” which takes as its subject the murders of, by some estimates, as many as a million people in Indonesia in the 1960s. The killers were never punished. In many cases, they became powerful people who proudly and publicly refer to their days of heroic government service as the exterminators of Indonesia’s “Communists.” The murder of all those souls was, until very recently, simply part of the national lore. There is another reality of course — the terror of the survivors and resultant silence of the families of the victims. Both are examples of constructed narratives, though only one is a grotesque manipulation of what transpired, a ghastly example of the way facts may be ignored to create a narrative as far from truth as can be.

One day left to check out Twelve Saints

Our sponsor Entre Ríos Books will be around for one more day. You really should check out the sample poem and artwork from Twelve Saints that we're featuring. It's stellar work, and — once again — we're so impressed and pleased with the quality of the sponors we've been attracting. You won't regret looking.

Did you know we only have two slots left in our first sponsorship block? If you were thinking about sponsoring us, now is a good time to reach out. We'd love to hear from you, and we'd love to partner with you — like we have with Entre Ríos Books — to make internet advertising 100 percent less terrible.

Rahawa Haile’s short stories of the day, of the previous week, for November 7, 2015

Every day, friend of the SRoB Rahawa Haile tweets a short story. She gave us permission to collect them every week. She's archiving the entire project on Storify

Short Story of the Day #302

J. F. Powers's "Death of a Favorite

New Yorker (1950) pic.twitter.com/mKDtbsePjT

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 2, 2015Short Story of the Day #303

J. F. Powers's "Defection of a Favorite"

New Yorker (1951) pic.twitter.com/ZYaIqqdsbL

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 2, 2015Short Story of the Day #304

Lee Matalone's "Now We Must Speak in the Past Tense" (2015)

https://t.co/j3pxru3qOH pic.twitter.com/AYn3Ddb40V

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 3, 2015Short Story of the Day #305

Sylwia Siedlecka's "Water Butterfly"

Guernica (2015)

https://t.co/guTPXrEyWr pic.twitter.com/AV6fVO6mLa

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 5, 2015Short Story of the Day #306

Dani Sandal's "Compass"

Monkeybicycle (2012)

https://t.co/wMjRySwmas pic.twitter.com/y6uueLDFwP

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 5, 2015Short Story of the Day #307

Maria Pinto's "Obituary"

https://t.co/fo9gbFD5yl

The Vignette Review (2015) pic.twitter.com/sIFUc4gQXu

— Rahawa Haile (@RahawaHaile) November 6, 2015Independent bookstore fan showrooms Amazon Books

When the news about Amazon Books was first announced, I tweeted this out:

Reward for the 1st person who takes a photo of themselves buying from an indie bookstore on their phone while standing in an Amazon Books.

— Paul Constant (@paulconstant) November 3, 2015If you were unaware, Amazon has actively promoted "showrooming," which is the act of standing in a brick-and-mortar bookstore, looking at a book, and then buying it on Amazon, rather than from the bookstore. You're using the bookstore as a showroom for Amazon, but the bookstore, which pays rent and salaries and all the other expenses of running a small business, gets absolutely nothing. BuzzFeed picked up my above tweet and ran it as part of a listicle about Amazon Books. My issue with BuzzFeed's listicle was that they included my tweet as a "joke." I was dead serious. So this morning, the good people at Shelf Awareness gave my tweet a signal boost and I clarified that I absolutely meant what I said:

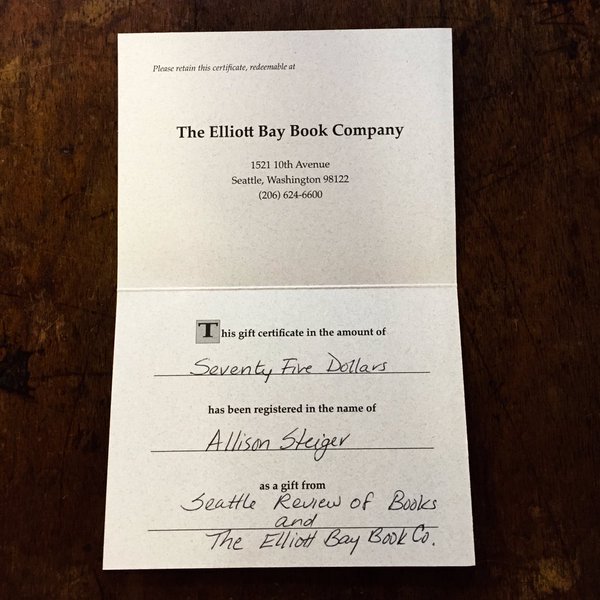

Serious offer: first person who showrooms Amazon Books gets a gift certificate to @ElliottBayBooks. Send pictures. https://t.co/h8e82wy8NA

— Paul Constant (@paulconstant) November 6, 2015It didn't take long for someone to bite. Twitter user Allison Stieger visited Amazon Books this afternoon. She found a book that she was interested in — Alice Hoffman's The Marriage of Opposites:

Buying this book from @queenannebooks after showrooming at @amazon Books. @paulconstant pic.twitter.com/2tL4TpUrlx

— Allison Stieger (@allisonstieger) November 6, 2015And then she bought it from the website of awesome local bookseller Queen Anne Book Company.

Done. Browsed at @amazon Books, bought from @queenannebooks @paulconstant pic.twitter.com/4TBouM2Bwh

— Allison Stieger (@allisonstieger) November 6, 2015And then she picked it up at QABC:

Done! @queenannebookco @paulconstant pic.twitter.com/ZOeVT1Ah7N

— Allison Stieger (@allisonstieger) November 6, 2015So there you have it! We made history today. Allison Stieger became the first person in the world to reverse-showroom Amazon Books, and she bought the world's first reverse-showroomed book at Queen Anne Book Company. Congratulations, Allison Stieger and Queen Anne Book Company! You've showroomed the showroomer. And Elliott Bay Book Company thanks you for it:

If you're looking to get out of town for a bit this weekend, consider this: Washington state publisher Two Sylvias Press is having an open house at their new offices in Kingston from 11 am to 5 pm, with wine, food, authors, and books for sale. Two Sylvias, of course, was founded by Kelli Russell Agodon, who was the very first poet we published here at the Seattle Review of Books. They've also published books by SRoB contributors Susan Rich and Michelle Peñaloza, as well as the estimable Esther Altshul Helfgott. The offices are a short walk from the Kingston ferry terminal. Seems like a great way to spend a fall afternoon.

NanoWriMo Week 2: It doesn't matter how you feel

So, how's progress? If you're on track, and getting your nut in every day, you should be about 10,000 words today. If you've cracked that milestone — congratulations! That's huge. If you haven't, don't despair. Buckle down over the weekend and get some hours in. This is the time to make it happen. Your book can't be read until you've written it.

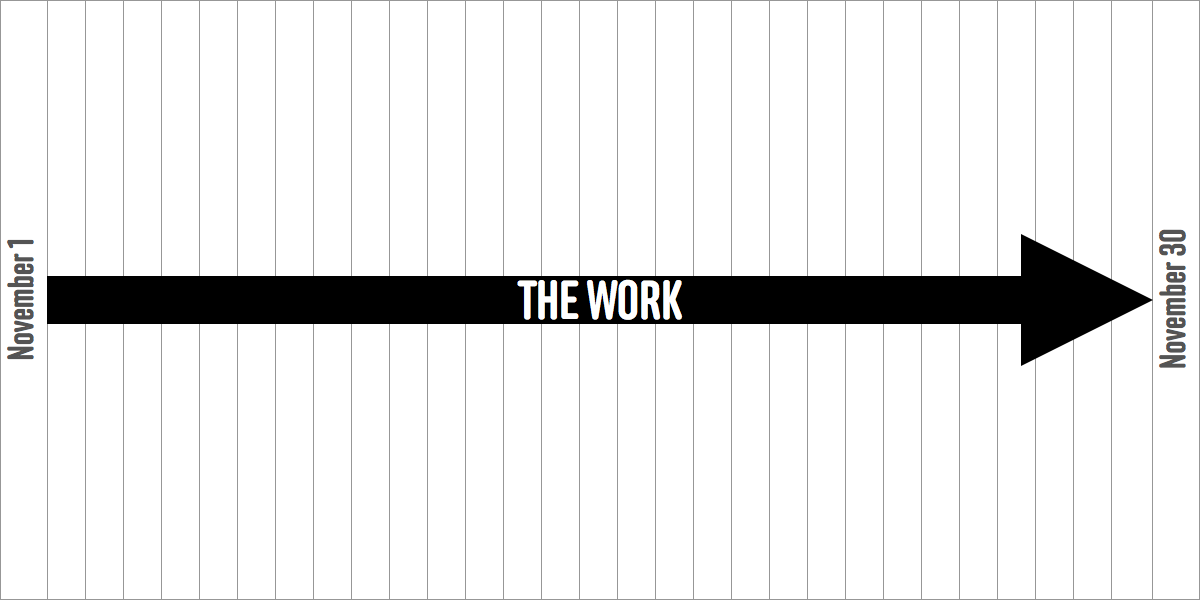

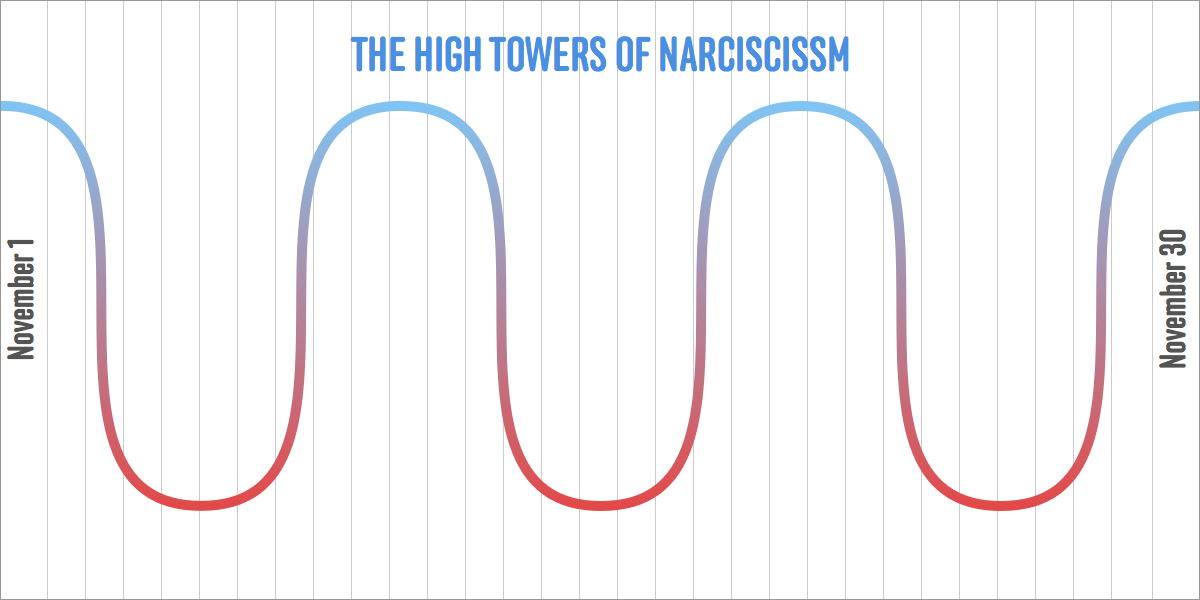

Today we're going to cover the sine wave that is a writer's mood when penning a novel. I even have some graphics! Let's start with the straight line down the middle:

That's you, writing. Imagine this is your timescale, in this case, one month (although, it can also be months or years, the process is the same). November 1 is to your left, and November 30 to your right. That black line across the middle is your work, as you forge ahead. This is how we think about writing, right? We'll apply ourselves and work diligently and achieve our goals in a straight line.

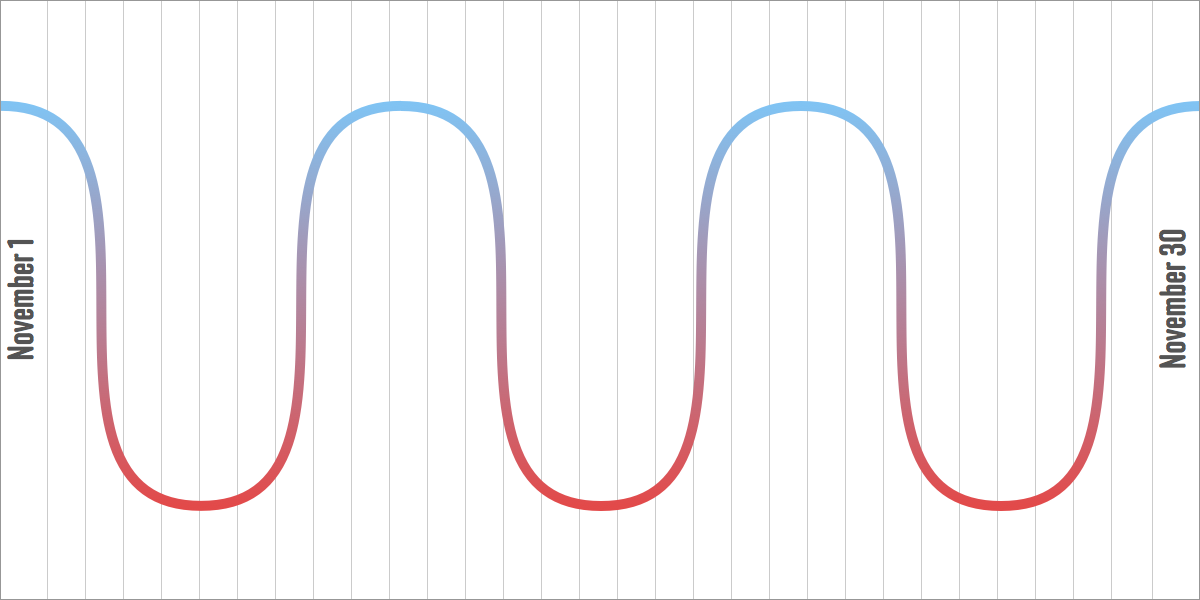

But, as humans, we have these things called feelings. They're pretty useful, but sometimes get in the way. Like, for example, when we're writing. Sometimes we feel great about what we're writing, and sometimes we feel awful about what we're writing. In fact, that emotion goes up and down with such regularity, that we can almost plot it. Simplified, it looks like this.

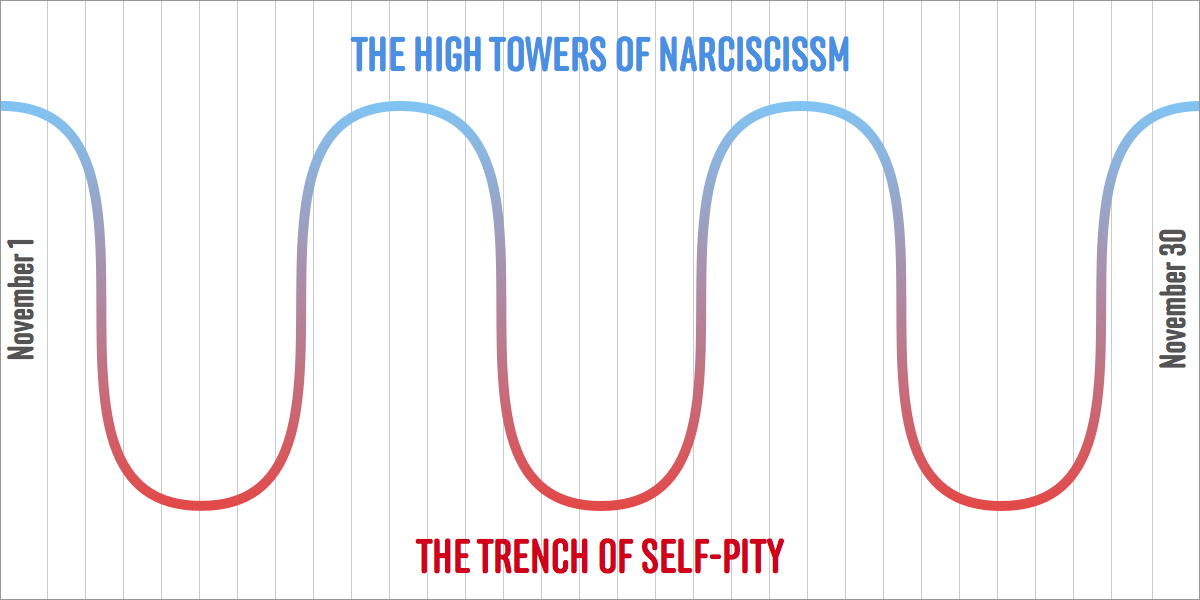

At the top, we're sure that what we've written is the greatest piece of writing the world has ever seen. In fact, they should just award us all the prizes right now, a Nobel, a MacArthur Genius, some of the more obscure ones, to boot. They'll make us the first photographic portrait cover on the New Yorker. MFA programs will start courses on us. Because, they'll see, no other human has, with such precision and clarity articulated the exact solution to every problem in the world, like we have on these ever-so-satisfying pages. We call this the:

And high they are. And narcissistic they are. But, that's okay. This feeling is delusional, but it is a true motivating factor. Nobody else will advocate for your unwritten book. You need you to be excited about it. You are its champion. You are, literally its raison d'être. So let's not take our cheerleading as literal truth, but let's acknowledge its purpose in our life, and let us be motivated, excited, and buffed by it.

As nice as the high towers of narcissism are, they are fleeting. Before too long, we're falling down the trough, across that line of our progress (say hello on your way down!), and we find ourselves wallowing in:

Oh god, this is the worst place ever. We're the worst writer the world has ever produced. What ridiculous fools we've been to think we can do something so asinine as write a book. Can you believe our hubris? Our idiocy? How trite every sentence is? How pathetic every metaphor? We should just crumple this piece of crap and walk away, never to write again. In fact, the world is literally demanding it of us, standing on our doorsteps waiting for us to just hand them our resignation from ever attempting to do art again. They have formed committees to search and delete all text we have ever put in the world, and President Obama has called for a congressional investigation into whoever the hell taught us to read in the first place.

Ugh. The trench is the worst. It's a pity party all the time, and nobody knows how to throw a pity party like a person trying to be creative and feeling like a failure. However, it's ironic, but true: we need the trench. The trench is what separates you from a true narcissist, someone who is truly delusional about their work. The trench sucks, but it is activated by that part of your brain that will later be a good steward and editor to your work. It is the part that is activated by wanting to be good. And we want to be good writers, yes? We want people to read our work and say "this book is so good, because that person is a really fine writer."

But the feelings of the trench should be activated later: when we're editing, and thinking about our work critically. At this point, the appropriate response is to say "Oh hey, look at that, I'm walking through the trench and I feel shitty. Guess I'll just get my words in anyway."

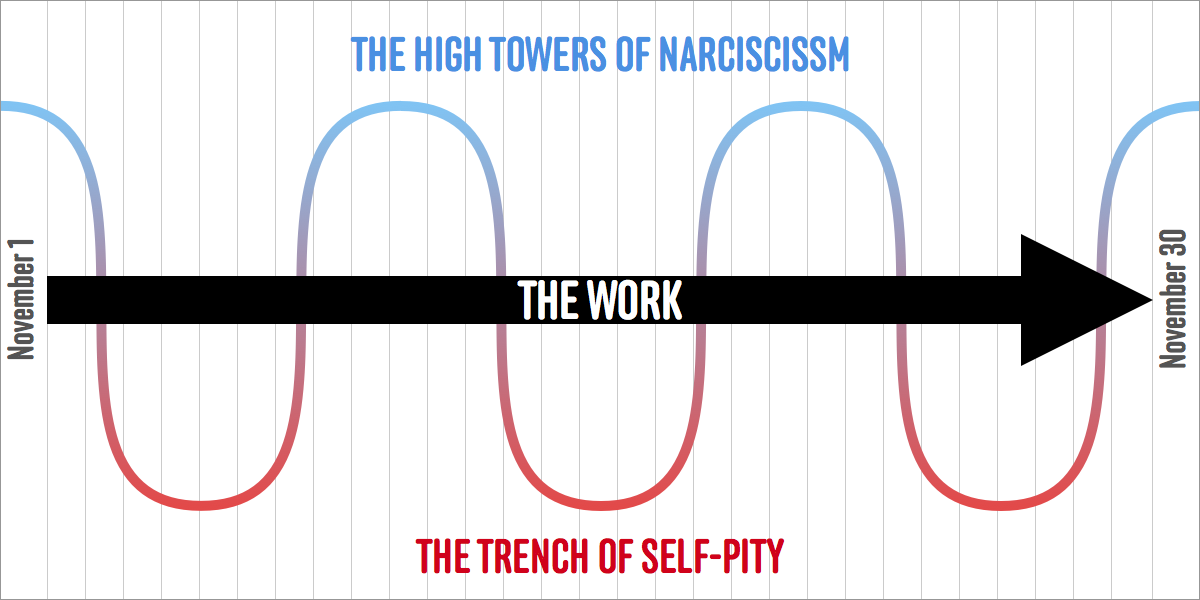

This is where it all comes together. Because that sine-wave is your feeling, but it's not the work. The work continues, like this:

Notice one thing about the black line: it doesn't change. When I'm sitting at my desk, and I'm triumphant in the high peaks of narcissism, I celebrate it by getting words out of my head onto the page. When I'm wallowing in the trench of self-pity I flop around in its cold humidity by putting words on the page. And when I rise out of the trench and can once again see the horizon, I rise while I write, and when I fall from the towers, I fall while I write.

And you may not believe me what I'm about to tell you, so you're just going to have to write through your own sine-wave and see this strange effect for yourself: you cannot discern a difference between your writing when you're feeling great about it, and your writing when you're feeling terrible about it. The writing through it all is consistent.

Your feelings are needed, but they are unreliable narrators to the quality of the words you are putting onto the page. Your job, during November, is only to get words on the page, not decide if they are good or not. Let your feelings ride the wave (you can't stop them, after all) and focus on your task of getting your words in. One word after the other, one sentence after the other, one paragraph after the other, one page after the other.

And when you've crossed that finish line, and got your words in and you're reading back through them, see if you can find the tower and the trench in the words themselves. If you can, tell me I'm wrong. I'm laying odds they'll be as invisible and fleeting as feelings in our past always are.

The Help Desk: How should a pacifist book-lover protest Amazon's bookstore?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I can't remember if my anger and frustration with Amazon began when I heard about the "gazelle" project, or when I heard about their total lack of philanthropic investment in our city, or what, but by the time the Hachette e-book price wars started up, my rage had reached a boiling point, and with the opening of their stupid bookstore, I am just seething. I hate what they've done to books and book publishing and everything I hold dear as a writer, editor, and reader. So my question is: how best to channel my rage? I already stopped shopping there, and I think my friends and family are honestly pretty sick of my virtual and in-person ranting on the subject. I need some new ideas for creative or constructive outlets for my Amazon hatred. Help!

Marybeth, Ravenna

P.S. I am a pacifist so violent direct action is not an option.

Dear Marybeth,

I understand your feelings of impotence and frustration. It would be melodramatic to say that Amazon ruined the publishing industry, the book selling industry, or Seattle. However, it's fair to say that Amazon waited until publishers, booksellers, and the city of Seattle as a whole was sleeping, took a big smelly dump on their chests and said, "you look like shit but that's not my problem."

A better advice columnist might tell you to take the high road and ignore their crappy business dealings but I'm afraid of heights so the high road is never an option for me. So what do you do? I suggest working to change the only item on your above list that you have a kitten's chance in hell of influencing: Amazon's philanthropic giving, which is laughable. It amazes me that with 24,000 employees in Washington state alone, and many of them Seattleites, those employees aren't demanding better from their employer. Instead of instigating poster wars that attempt to shame Amazon tech bros for moving to Seattle and "ruining" neighborhoods, why aren't Seattleites banding together to demand Amazon be a better philanthropic presence in the city that has contributed greatly to its success?

There are enough readers, writers, booksellers, sympathetic Amazon employees, and liberals in Seattle to put pressure on that company to change its corporate structure in one small way. How to accomplish that exactly, I can't say. Someone who's well versed in organizing, rather than telling alcoholic librarians what to do every Friday, should come up with a plan. (The only protest I can claim participation in took place last Christmas when, after a bathtub's worth of hot buttered rums and gin! Gin! Gin! my liver went on strike.)

Affecting change in that way, I believe, would make a satisfying difference.

(If it doesn't, you could always try taking a dump in front of their store. That also makes a satisfying difference.)

Kisses,

Cienna

The Associated Press says:

SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — Chile's government is acknowledging that Nobel-prize winning poet Pablo Neruda might have been killed after the 1973 coup that brought Gen. Augusto Pinochet to power.

The Interior Ministry released a statement Thursday amid press reports that Neruda might not have died of cancer.

The statement, in fact, says it's "clearly possible and highly probable" that the poet was murdered. Hopefully, at least, morbid curiosity will drive new fans to Neruda's work. He's certainly been in the news a lot recently; Washington's own Copper Canyon Press revealed in July that they're publishing a new volume of "rediscovered" Neruda poems early next year. All this attention might mean Neruda will top the bestseller list again. Dictators of the world will never learn that you can't kill a poet's work — by killing the person, you only give their words more power.

If you're upset about Tuesday's election results leaning very conservative across the country, you really ought to go to Town Hall tonight. Ari Berman, who was kind enough to do an Election Day interview with us, will read from Give Us the Ballot, his compelling history of the struggle for voting rights in America. Berman will also be in conversation with Washington state Supreme Court Justice Steven Gonzalez about local results and what we can do to increase voter turnout here. This is a huge issue, and it's not going to go away by itself. Berman's meticiulous research provides him with a unique perspective on how we can solve America's growing democracy problem.

Portrait Gallery: Gloria Steinem

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

The one-and-only Ms. Steinem appears Sunday at Benaroya Hall, in conversation with Cheryl Strayed, sponsored by Hedgebrook. This is going to be a very interesting night.

It's almost time for holiday shopping. But before we get down to the arduousness of — ugh — buying books for other people, you should visit Third Place Books and Third Place Books Ravenna this weekend. On Saturday and Sunday, all used books in both locations are 40 percent off. It's one of my favorite book sales of the year, and a great chance to get some selfish book-buying done before it's time to start thinking of other people again.

Stop me if you've heard this one

Has anyone yet written a how-to-write book for how-to-write books? If it hasn’t happened yet, we’re probably closing in on that moment in literary history. Lots of people — myself included —enjoy being hypnotized by the soothing rhythm and encouraging cadence of how-to-write guides. After a certain point, all the tips and tricks and affirming quotations blend together into a whirl of positivity, but a good writing guide stands out: Stephen King’s On Writing is one, and Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird, and John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, and Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones. But there are so many terrible writing guides by writers with unrecognizable names; at some point, someone is going to compose a guide to writing writing guides, and that book will probably sell surprisingly well.

I bring this up because last night’s Word Works lecture by Benjamin Percy at Hugo House had all the familiar cooing cadence of how-to-write books, but Percy did not manage to deliver one original thought in his entire 45-minute talk. All he offered were writing-guide clichés, polished and lined up for presentation. Perhaps a good writing guide for writing guides would have warned him away from the perils of using stale language to discuss the writer’s craft.

Ostensibly on the topic of “blending genre,” Percy's talk instead focused on the difference between literary fiction and genre fiction, mostly by relying on tired examples of both. To hear Percy tell it, literary fiction involves tea and staring out windows, and genre involves high-octane, propulsive writing. Though he invoked any number of great and nuanced writers in his talk — Aimee Bender, Karen Russell, George Saunders — Percy continually relied on broad generalizations to discuss the point of literary fiction and genre fiction, and the differences between them. Generalizations can be useful tools when you're making an argument, but Percy zoomed so far out from the point that it was impossible to argue with him. When he categorized all the books in bookstores as books that "suck" and books that "don't suck," it became clear that this was not going to be a nuanced discussion.

So what makes great genre writing? Percy began by talking about his childhood experiences with Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman movie and the Stephen King novel The Dark Tower. He was disappointed by the movie, but became obsessed with the book. Why is that? The movie, he concluded, had no heart. The book, though, had heart. Bad genre fiction ignores characterization, he said, and bad literary fiction ignores plot. Fantastic elements in fiction should be stones that are tossed into a pond, and the effects of those fantastic elements are the ripples. There’s nothing new or particularly insightful in these observations, and this is about as deep as the talk went.

Some other writing-guide clichés that Percy pulled out: “we need the everyday to balance out the astonishing,” good writing “makes the extraordinary ordinary,” and he referred to good characters taking over a story despite a writers’ best intentions. You might argue that the clichés in Percy’s speech were acceptable because he was telling truths about writing. Okay. Lots of writers speak in awed tones about those moments in which characters seemingly came to life and took over a narrative, and plenty of sci-fi writers talk about the importance of inserting reality into a fantastical story. Lots of writing instructors refer to actions in stories as stones tossed in ponds.

But one of a writer’s most sacred duties is vigilance against cliché. Clichés demonstrate laziness, and if you encounter clusters of them in a piece of writing, you should begin to doubt the quality of thought that went into the piece. When a writer discussing the craft of writing relies on cliché to make his argument, his audience should treat everything he advises with great suspicion. Despite the content of his speech, Percy came across as an earnest, likable person. But the gruel he doled out from behind the podium last night would best serve as a guide for how not to talk about writing.

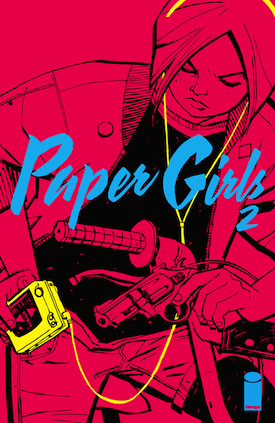

Thursday Comics Hangover: The weird dawn light of Paper Girls

We're in a golden age of Brian K. Vaughan comics. I can't shut up about how good Saga is; he recently wrapped up The Private Eye, a beautiful sci-fi comic with Marcos Martin; his Canadian future war comic We Stand On Guard keeps getting better; and his newest series, the retro sci-fi adventure comic Paper Girls, is probably his best non-Saga comics work yet. Co-created with artist Cliff Chiang, Paper Girls tells the story of a group of newspaper delivery girls in 1988. One day, they encounter some monsters. The audience is introduced to an object that suggests time travel might be involved. The second issue, released yesterday, adds to the mystery by tossing in some more monsters and a very confused adult.

Paper Girls is reminiscent of the J.J. Abrams movie Super 8 in that it's a genre story that's soaked in nostalgia for 1980s childhoods. But while Super 8 collapsed under its own weird self-regard — did the world really need a Spielberg homage produced by Stephen Spielberg? — Paper Girls hums along by keeping the postmodern winks to a minimum. Sure, the characters argue about pop culture; when one character calls Peggy Sue Got Married a sci-fi movie, another delivery girl can't resist a little fannish pedantry: "That's actually more of a fantasy time travel story," she says. But this meta-commentary feels appropriate for the story and not at all forced.

Fresh off a career-making turn on Wonder Woman, Chiang proves to be exceptionally suited for a comic like Paper Girls. The girls are realistic teenagers (hooray for a complete lack of creepy objectification!) and the monsters are happily comic-booky. Chiang's genius, though, is that these disparate elements somehow obviously exist in the same universe; they each have equal weight. From the mundanity of an abandoned Big Wheel on a street corner to the bizarre vision of a werewolf in a Guns N Roses t-shirt stagering around, Chiang keeps everything tight and consistent.

Paper Girls also stands as a representative example of what good coloring can do for a comic. Matt Wilson uses an 80s-appropriate neon palette for the covers and special effects, but most of the book takes place at an eerie moment of dawn — or is it dusk? — when the sky is a washed-out rainbow of deep purples and royal pinks. Anyone who has ever run a paper route remembers the eerieness of waking up at pre-dawn when the whole world is asleep; Wilson captures the glow of that moment on paper and makes it real.

It's unclear at this point exactly where Paper Girls is going, though it's obvious that Vaughan has a plan in mind. It could become a full-on creature feature, or it might be a twisty time-travel story, or it might be a tribute to the friendship between girls. Knowing Vaughan, it'll likely be some combination of all three. Whatever happens, I'm entirely onboard; Paper Girls has rocketed to the top of my list of must-read books.

Burglars stole nearly a thousand dollars from the delightful Couth Buzzard Books on Greenwood Ave over the weekend, reports Phinneywood.com. That's a lot of money, especially for a store that's still a month away from the holiday rush. On the Couth Buzzard Facebook page, owner Theo Dzielak writes:

Some of you have asked how you can help. Well, come on by and say hello, grab a great drink, some food and check out our great selection of new and used books.

That's wonderful advice. Maybe plan a little trip to the Couth Buzzard this weekend? If you buy one or two books, that would go a long way toward recouping their losses.

The internet can't stop talking about Amazon Books

Yesterday saw an avalanche of think-pieces and first-person accounts of the launch day for Amazon Books, the online retailer's first physical bookstore in University Village. The most notorious of these hot takes was Megan Garber's piece for the Atlantic, titled "Did Amazon Just Replace the Public Library?" I honestly can't tell if Garber's piece is supposed to be a joke or a troll or not. It certainly reads like it's trying to be funny.

Garber begins by extolling the beauty of Apple Stores, saying they "celebrate both introspection and communion. They are meant to humble and inspire." She also seems to think that bookstores are a nostalgia act: "There’s a lot of wood. There are a lot of shelves. There are a lot of books! The dream of the ’90s is alive in Seattle, apparently."

Seriously: is there any way to interpret the comparison of Amazon Books to "a Barnes & Noble of yore" as a serious statement? Or Garber's assertion that "Amazon has always been, implicitly, about community?" (Amazon is all about buying books without the intrusion of community. Specifically, you go to Amazon if you want to buy something without human interaction. Posting a one-star review of Hamlet is not a substitute for person-to-person communication.) And the neck-snappingly pretentious paragraph that concludes Garber's piece reads like satire:

...Amazon Books could become something else in the process, emulating institutions that have been their own kinds of cathedrals: libraries. Which have traditionally been just what Amazon is aiming to create: spaces that are premised on books, but realized by community. The books here may be bought rather than borrowed, certainly, but in terms of the space created, the goal is the same. Amazon Books is a store doing the work of a cultural institution. It’s about commerce, yes, but it’s also about collectivity. It is, in form if not in name, a library.

Uh, no. It is, in form and name, a bookstore. Libraries are places where you can borrow books, but those books belong to a larger community. Bookstores are where you go to buy books. Perhaps the problem is that Garber seems to believe bookstores don't exist anymore, even though Seattle booksellers are right now more profitable than they've been in a generation.

The best thing I can say about Garber's piece is that it spawned a wonderful little Twitter rant by APRIL Festival co-founder Willie Fitzgerald about the APRIL origin story, which involves the sadly defunct Capitol Hill bookstore Pilot Books. Click through and read the whole story:

Holy fucking christ my eyes started bleeding two grafs into this goddamn nonsense

https://t.co/cVHUNYTd27

— Willie Fitzgerald (@williefitz) November 3, 2015Meanwhile, the reviews are coming in for Amazon Books, and they're generally confused. For Ars Technica, Sam Machkovech reports that the bookstore is a shallow dive into a poorly stocked collection that might just be "an ideal shopping experience for some clueless book shoppers."

Seattle Review of Books contributor Judy Oldfield sent along her experiences at Amazon Books in an email. She kindly agreed to let us excerpt her account here.

I looked for books by Naomi Jackson, Dolen Perkins-Valdez, and Mona Eltahawy. I looked for these because they are all by women of color and all writers who read at Elliott Bay [Book Company] this year. I know that our local indie stores sell them, because I bought all of them from either EB or University Book Store. Amazon didn't have any of them...The local authors table included Where'd You Go Bernadette, and The Art of Racing in the Rain as well as books about Boeing and Pete Carroll. But I didn't find anything by Matt Ruff or Nisi Shawl (there or anywhere else in the store). Seems like to be celebrated as a local author, you must either have a restaurant, write about something/someone famous, or have a bestselling book.

Oldfield also pointed out a glaring problem with Amazon Books carrying such a limited inventory: their comics selection is weirdly spotty. They carry many copies of a single graphic novel, but they don't carry all the books in a series. For example, "they have about a dozen or more [copies] of Fables vol 1. For Ms. Marvel, it's volume 3. For Saga, they had both volumes 1 and 5, but they weren't next to each other. For Sex Criminals, only volume 2."

I can tell you that the second volume of Sex Criminals isn't going to make much sense without reading volume one first. But what happens if you ask for the first volume of Sex Criminals at Amazon Books? Reportedly, the booksellers helpfully suggest you order it on Amazon.com. So the bookstore exists to promote the website by driving people to the website to make up for the bookstore's shortcomings? What a weird, recursive experience.

Ada's Technical Books is our November Bookstore of the Month

Danielle and David Hulton didn’t know anything about running a bookstore when they founded Ada’s Technical Books five years ago. That’s probably for the best — the bookselling industry has been dying for at least four decades, according to the bookselling industry. Experienced booksellers tend to get so mired in gloom and doom that they’d likely never get around to opening a new bookstore. Sometimes it takes a novice to get it right.

Ada’s Technical Books started as a small science-minded bookstore (“for the cravings of the technical mind,” says the website) in an unexceptional space at the north end of Broadway. In 2013, the Hultons moved the store into a house on 15th Ave E, adding a cafe, a reading room, and expanding the stock significantly, including a larger science fiction section and more scientific paraphernalia like little robot-building kits and an array of puzzles. (Longtime Seattle book-lovers recognize Ada’s space as the old home to used bookseller Horizon Books.) This is the kind of bold move that you wouldn’t expect a bookstore to make in the 21st century, but it’s certainly paid off for Ada’s. And they’re still expanding the idea of what a bookstore can do; last year, the store opened up a coworking space in the attic providing work stations and a pair of meeting rooms for people in need of a professional work environment.

Ada’s succeeds because it’s a thoughtful enterprise. So much detail has gone into making the store a welcoming experience, on every level. The cafe serves excellent food made from scratch, not just a bunch of previously frozen baked goods from the back of a Sysco truck. The staff’s expertise shows in the books they carry: Ada’s doesn’t have every book on geography, computer science, or astronomy, but they do carry the best books on those topics. The store is home to an array of book clubs hosted by passionate booksellers, as well as a monthly puzzle night and a proudly geeky event series. They host an annual Buckminster Fuller party, and a bimonthly science discussion club.

It’s a little tricky to describe Ada’s to the uninitiated: the words “technical book store” sound a little intimidating. Tell someone that Ada’s primarily carries science books, and odds are good you’ll watch that person’s eyes glaze over. But what becomes readily apparent when you walk in the door at Ada’s is that there is something there for everyone. The childrens’ books and science fiction sections have grown in the years since the store moved to 15th, to better suit the neighborhood. If you spend five minutes browsing the stacks you’ll find something — a biography, a how-to manual, a study of brain chemistry— that grabs your interest and refuses to let go. Ada’s happily provides proof that we can find universality in specificity.