Kissing Books: The Niceness Industrial Complex

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

The more people there are around you, the easier it is to disappear.

You can be anonymous in a city, if you want: travel to a new neighborhood, or try a new restaurant, and you encounter a whole different circle of strangers. But in a small town, everyone knows who you are. Everyone’s always watching, judging, gossiping about the ups and downs of everyone else’s life. No wonder so many romance novels and series take place in small towns: a small town makes everything significant, and a romance novel is all about the life-changing significance of ordinary things. A ring, a letter, three small and well-worn words.

For a long time I was grappling with why small-town romances felt like historicals to me — but it’s only very recently that I stumbled over part of the answer. Author Jennifer Hallock’s presentation for this year’s IASPR conference (that’s the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance — they have a wonderful journal!) introduced me to the delightful term chronotope, which is a shorter, fancier way of saying the way in which fiction represents time and space. Hallock’s work looks at the Regency/Victorian chronotope in romance to explore why there are more fictional dukes than real ones, and the shocking reason why none of them are afflicted with historically accurate syphilis (spoiler: it’s because syphilis isn’t sexy).

If we can consider the historical romance as establishing a chronotope primarily of time, then I think there’s a case to be made for the small-town romance subgenre as maintaining a chronotope of space. There is often a faint sense that these places are somewhat set apart from the wider world, like Brigadoon or Camelot. So many of these towns are not meant to be real so much as they’re meant to be Nice: idyllic Main Streets lined with non-franchise diners and art galleries and cupcake bakeries, near some pristine body of salt- or fresh water. They often have cutesy or openly symbolic names: Virgin River, Lucky Harbor, Sweetwater Springs. They promise comfort in turning away from the troubles of the real world. I don’t mean this as a blanket dismissal of the form: legion are the readers who pick up a small-town romance in the hospital, or when grieving a loss, because they need to find one small place in which nothing truly bad can happen. We need books that soothe as much as we need books that startle. Done well, these comfort reads can be engrossing, dreamlike, and restorative.

Unfortunately in this world some people’s comfort counts more than others’ — and as Sondheim says, Nice is different than Good. Some authors, in attempting to write something Nice, choose to erase entire groups of people from their fictional landscapes. Some kinds of bigotry don’t depend on malice: they depend only on your willingness to believe that, say, race or queerness only belongs in certain kinds of stories. This is the stunted logic that says queer people shouldn’t appear in sweet or cozy stories, because queer people signify sex — and people of color shouldn’t appear in stories that aren’t about race, because people of color produce racism out of thin air simply by showing up. So you get fictional rural towns full of lily-white, stick-straight characters. And then you label these places “safe,” in ways that books with non-default characters aren’t. Next thing you know you’re using “urban” to describe a character when what you mean to say is “black” — because you’ve internalized the rural=white myth and you think describing someone’s skin color is rude. Because you think it’s like pointing out something that’s wrong with them. And that’s not a Nice thing to do.

Do you see how you’ve just shored up white supremacy a little bit more? Do you see how you’ve erased queer people from your make-believe corner of the nation? If you let yourself believe queer people shouldn’t exist somewhere, it’s a very short leap to believing they shouldn’t exist anywhere. In trying to keep your story Nice, you’ve fertilized the pernicious lie that small towns are naturally white, straight, and conservative — when in fact, in the real world, many of those places systematically drove out the queer folks and people of color who did live there by legislative discrimination, redlining, and sheer brutal violence. Your attempts to be Nice have made straight white people’s comfort a higher priority than people of color and/or queer people’s right to exist. You’ve bought into what Ijeoma Oluo describes as the promise of racism: you will get more because they will get less.

This whole tangle, which I’ve started referring to as the Niceness Industrial Complex, put me off a lot of small-town romance for a long time — until I found that it doesn’t have to be this way. Whiteness/straightness is not actually a genre requirement. There are other series that use the small town’s set-apart quality to foster a less narrow, or even subversive space: Lydia San Andres’ gorgeous Edwardian-era tropical island of Cuidad Real; Alisha Rai’s exuberantly inclusive Forbidden Hearts series; Victoria Dahl’s staunchly feminist small-town heroines; Beverly Jenkins’ black-centered communities in books like Vivid, Forbidden, and the Destiny trilogy; Rebekah Weatherspoon’s mountain retreats in Haven and Sanctuary (speaking of symbolic names!); Rose Lerner’s Lively St. Lemeston Regencies with historical British Jewish rep and servant-class heroes and heroines. All these settings give us vibrant, engaging communities where all kinds of people love and are loved. They preserve the escapism of the chronotope without indulging its harmful prejudicial tendencies.

Three of this month’s romances are set in small towns: Erin Satie’s Bed of Flowers, Carla Buchanan’s Pride and Passion, and Farah Mendlesohn’s Spring Flowering. Jude Lucens’ Behind These Doors and Farrah Rochon’s Cherish Me take place in cities, but have a close-up focus on families (both the ones you find and the ones you’re born into) that gives them a small-town sense of interconnectedness: everyone knows who you are, and everyone’s a part of your history. Some of these settings are protective; some are suffocating; one is practically Orwellian in the way it surveils and punishes its characters for breaking social norms. Though the characters are frequently kind — Spring Flowering’s Ann in particular is a paragon of thoughtfulness — none of these books are Nice in the way I’ve described. The questions they ask are difficult, and often painful: what does it mean to be good? What do I owe to the world, or to my partner? What can I do to work toward happiness in the face of grave injustice and hurt?

These are questions always worth the asking, even when we think we have the answers.

Recent Romances:

Bed of Flowers by Erin Satie (Little Phrase: historical m/f):

I am abashed it has taken me this long to read something by Erin Satie — but lord was it worth the wait. This Victorian romance is a whole world in miniature: a moral-minded port town recovering from a devastating fire, an impoverished beauty newly engaged to the handsomest man in the neighborhood, and a misanthropic baron who sleeps in the greenhouse where his rare and delicate orchids grow. Everything is a delicate balance of old resentments, hidden agendas, and smouldering pain — how could there not be a scandal brewing?

This kind of thing generally follows an established pattern in historical romance: first, the heroine flouts polite convention in ways a modern reader will find sympathetic. Usually by having sexual desires or intelligence or wanting meaningful independence, that kind of thing. The resulting outcry becomes a litmus test whereby we judge the other characters: those who condemn are Bad and therefore Ignorable, and those who support the heroine despite the stain on her reputation are Good, and therefore Worthy. It’s rare for a character depicted as loving to end up on the Bad side of this equation.

This book asks a more difficult question: what if being good came with real, painful consequences? What if doing the right thing cost you your family — even if they still claimed to love you?

Bonny, our heroine, makes her fatal choices as we watch. Our hero Lord Loel’s moments of decision happened in the past, and are revealed in conversation as he and Bonny work out what they mean to one another. Both characters put saving a life above family advancement, and both suffer for it. Real suffering, not merely the oh no who will invite us over for tea now? kind of mild social consequences modern romance so frequently presents as disaster. Here things are far more serious: financial ruin, abusive language, mob violence, and the subtler pain of refusal of services (market stalls won’t sell to Lord Loel, for instance, which is no small burden in a small town).

At one point a wealthy London socialite — whose wealth insulates her from a lot of the moral quandaries other characters are forced into — explains that with scandals, “We are more forgiving of our friends than our foes.” This book lays bare the uncomfortable truth that the scandal trope’s moral test is usually merely a sop to the reader’s modern sensibility. Bed of Flowers shows how even a loving, thoughtful family — a beloved sister, a pair of parents whose own marriage is solid and supportive — can choose to shun a daughter who has erred in the eyes of the world. There is no reconciliation at the end to erase all the pain. But this refusal to satisfy with an easy out makes the romance far more meaningful — it has weight to it, because something was given up on its behalf. It feels like the start of something genuinely new. The next book in the series has a biracial novelist heroine, and you can bet I’m already pretty excited about it.

He was handsome, too, but in a feral way. All his features were sharp: his cheekbones were sharp, his chin was sharp. Even his nose sloped down to a sharp point. He looked like a man who, if he tried to give a lady a kiss, would cut her instead.

Cherish Me by Farrah Rochon (Wandering Road Press: contemporary m/f):

Marriage in trouble books disprove the idea that romance narratives are purely courtship-centered stories that end when the protagonists say their vows. As we saw with Emma Barry and Genevieve Turner’s A Midnight Feast, you’ve got to set up problems that feel like real obstacles, then knock them down in a way that feels like substantive progress. It’s about as hard to do this in fiction as it is in real life. This book is one of the strongest examples of the form I’ve ever read. I believed in these characters wholeheartedly, even when they were struggling to believe in themselves.

Rochon sets this up elegantly by taking the time to give the reader a full family portrait through the eyes of our hero and heroine — because of course this isn’t just a marriage with two people: it’s a family, with children and siblings and cousins and everyone’s hopes and disappointments and pressures inherent. The detail builds in layers, scene by scene, each small problem piling up until they make a mountain: hero Harrison’s concerns about a pending legal case, heroine Willow’s worry about her son’s pre-diabetes, their daughter’s teenage angst, the recent loss of Harrison’s mother, all viewed through the lens of a relationship that has suddenly, mysteriously ceased to be the source of joy and support that it once was. It’s a lot, and in the roughest moments it just feels like nobody has enough time to deal with everything that’s happening. This is all very everyday drama, but in Rochon’s capable hands it’s irresistibly compelling. Touches of humor soften the angst, and cameos from past series heroes and heroines offer tantalizing glimpses of earlier stories: a Vegas elopement, a playboy settling down with a comic-book artist.

This book is not entirely escapist, I think, but it is a testament to the necessity of escapism. Harrison and Willow can’t work on the problems between them until they’re removed from their usual haunts and habits. We first get to know them in the midst of their ordinary lives — then we watch as an anniversary trip to Italy helps them blossom into fuller, better versions of themselves. (Rochon is a dedicated traveler and her descriptions of the sights are one of the book’s great pleasures.) Deeply grounded, poignantly felt, and spiritually generous, this is one of those romances that feels like more than entertainment. It feels like you’re watching two people learn how to be better, happier human beings, and sharing in their mutual joy.

What she wouldn’t give to click her heels three times and return to the relationship she’d shared with Harrison for the nearly two decades they’d been together. You’re in Rome, not Oz.

Behind These Doors by Jude Lucens (Greenwose Books: historical m/bi m):

At the start of this book we have an Edwardian-era upper-crust poly trio in a long-established relationship, and one lonely gossip journalist with class consciousness issues. By the end of this book we know a whole ensemble of people whose search for personal happiness and political agendas we’ve had to factor in: members of parliament, militant suffragettes, queer men and women, bigoted family members, snobby newspaper editors, former streetwalkers and their families, valets, footmen, seamstresses doing piece-work, cooks, Boer War veterans, people of color, and disabled characters of both the upper and lower classes. It was incredibly transporting, a very persuasive snapshot of Edwardian London.

That's not all — there’s a great many other things this book does exceptionally well. Aubrey Fanshawe, our bisexual aristocrat with a tendency toward self-deprecation, is adorable and clumsy and utterly charming. Lucien Saxby, an army survivor turned gossip journalist painfully aware of the gap between his working-class roots and the nobs he writes about, is fascinating as someone who both desperately wants to care for someone and desperately wants not to be depended upon as a servant. The last thing he needs is to get entangled with a whole passel of aristocrats — so of course that’s where he ends up. Poly romances are always most interesting to me when they use polyamory not for cheap drama, but to show the process of constant negotiation and communication required to sustain a web of relationships so complex and vulnerable. This story reminds me of the poly characters of Solace Ames in the way small shifts in one person’s thinking can add huge amounts of tension to a relationship. Everyone has the best of intentions toward themselves and others — well, except for the bigoted relatives — but there’s still so much pain and conflict and real risk involved in telling someone how you feel about them, and learning where you stand in return. It’s the kind of charged story where every exchange matters: two characters argue over where to store a pair of sapphire cufflinks after they’re removed and you know it’s a stand-in for an argument over Who They Are and How They View the World. Recommended if you’re in the mood for Merchant Ivory-style pining and costumes, but without the crushing tragedy.

Swaying with the carriage, Aubrey stared at him in silence. Stark white lamplight glared through the windows, then faded into darkness, over and again. White shirt and pale face gleamed between the black coat and tall top hat, then disappeared into shadow: perfect symmetry revealed and then snatched away in regular, tantalizing rhythm.

Pride and Passion by Carla Buchanan (self-published: historical m/f):

The Decades series, with one black-centered historical per decade of the 20th century, has been an absolute godsend for people like me who love seeing romance authors branch out into less well-traveled historical eras. Carla Buchanan’s entry for the 1950s shows the budding love between a Korean War veteran and his friend’s widow, with the Civil Rights Movement as informing context. While heroine Constance navigates the shifting, unsteady pathways of mingled public and private grief, hero Nathaniel struggles with the emotional legacy of an abusive childhood. The questions are vital and universal: how do you move on from devastating loss when it’s all anyone can see when they look at you? How do you find purpose and joy in a world with so much tragedy built in?

I was pleased and charmed at the start of the book, and the more I read the more profoundly I was moved. There’s a quiet depth to this book that soothes the troubled soul. The characters are layered and self-doubting but the prose is frank and clear as crystal, which makes the moments of highest drama land with a resonant weight I can only describe as Shakespearean. At several points I actually gasped aloud. The book has a longer timeframe than many romances — entire years occasionally pass between chapters — but that expansiveness suits the story beautifully. Nathan’s carefully controlled strength pairs nicely with Connie’s fierce tenderness, and it’s easy to see why they fall so hard and so fast for one another. Easy to see what keeps them apart so long, too. Of all this month’s romances, this is the one that is most openly ambivalent about the nature of a small town: it’s home for Connie, and becomes home for Nathaniel, but it’s clear that the comfortable bubble to be found there can be stifling as well as protective. Perlshaw, Georgia is a safe place to heal, but there comes a time in every healing when bandages should be stripped away and the world must be explored and enjoyed and confronted once again.

You see, Constance knew she had to grieve. She knew she had to grieve, but she also knew she had to live as well. And because grieving felt so much like joining Al in death, life was what she chose even though no one else chose that for her.

This Month’s Historical With Double the Heroines

Spring Flowering by Farah Mendlesohn (Manifold Press: historical f/f)

Lately I’ve been craving a good f/f historical and it’s been surprisingly hard to find. So hard, in fact, that I started writing one. All I wanted was an Avon-style Regency with two heroines — why was this such an impossible quest? Finally, someone recommended Spring Flowering to me, and I’m so grateful they did. This is absolutely a romance reader’s romance — delicate and subtle and complex, playing with tropes and expectations and story rhythms like a virtuoso at an antique ivory keyboard. It’s some of the best Austen I’ve seen outside of Austen. This is also definitely an older style of romance: the story is told all from one heroine’s perspective, with part of the challenge for the reader being to puzzle out the real love story hidden in plain sight. Someone turns cold to our heroine for no reason — but of course there’s secretly a reason! Someone blushes at odd moments and her speech seems laden with double meanings — but of course the experienced reader can guess why! Ann, our pastor’s daughter heroine, has been knocked off-course by first her father’s death and now a move to the manufacturing town of Birmingham, impeccably rendered: we discover her as she rediscovers herself, going from wounded and hesitant to strong and self-principled. The ending is a beautiful, quiet triumph, and the more I think about it the happier I feel. To say too much about this book is to risk marring the reading of it, so I will simply leave you with one of the best and swooniest quotes, as one character grants Ann a lock of her hair:

“Do you remember the fairy tales were were told as children, and the one where the giant kept his heart in the ring in his nose? My heart is in this curl, Ann. Do not lose it.”

Thursday Comics Hangover: The quiz kid raises a family

Michael Kupperman has for years been producing very funny comics for outlets including the New Yorker and McSweeney's. His work has been published in books from Fantagraphics and HarperCollins. But just when you think you've got the cartoonist figured out, he sweeps your legs out from under you: Kupperman's new memoir about his relationship with his father, All the Answers, is something special.

Decades before Michael was born, Joel Kupperman was an early television star, a quiz show celebrity whose talent — the ability to quickly and accurately perform complex math in his head — made him a beloved figure. Like most early fame, Joel's celebrity washed away. And as an adult, he refused to discuss his years as a quiz kid.

Kupperman takes great care to redefine his comics vocabulary in All the Answers. The art is very obviously still his, but the rhythm of the book is different — slower, simpler, more accessible. That's not to say that he's slumming at all: though Kupperman often only relies on two panels per page here, the relationships between those panels can be very complex.

A portrait of Henry Ford, for example, stares out at the readers from in front of a busy background that resembles TV static. The "camera" pulls back further to reveal that Ford is a portrait on a wall. The wallpaper is comprised of hundreds of thin, dense lines. Standing in front of the Ford drawing in the second panel is Adolf Hitler. It's an obvious representation of how Ford's anti-Semitism influenced world leaders like Hitler, but those clashing backgrounds also tell a thematic story about chaos and control, about personality and its influences.

Kupperman uses that kind of transition often, particularly when dealing with his relationship with Joel. The perspective in a panel will back up a step or two between panels, to illustrate the distance between Joel and Michael, and the distance between the past and the present.

As Joel ages, he grows more and more bitter about his childhood experiences. Some of that rage eventually seeps into Michael, and All the Answers feels like an attempt to harness that anger, to keep it from infecting a whole new generation.

Kupperman's self-portrait in this book is a fascinating choice: the whorls of his hair are visually appealing, and the clean bold lines of his face have an attractive curve to them. He looks friendly, except for the eyes. Kupperman draws his own eyes as tight little circles that are too small for his face. They don't wink or tense or widen. They could almost be buttons sewn on top of his eyelids, and they give him a kind of impenetrability. It's hard to emote when you don't have access to the range of emotions that a pair of expressive eyes can provide.

I think with those eyes, Kupperman is establishing a distance between himself and the reader — the same way his own father held himself back from being too emotional with his son. This could be off-putting for some readers, who might believe that the point of a memoir is to be as emotionally open as possible.

But really those immobile eyes are essential to the story: if Kupperman were as forthcoming with the reader as other confessional memoir writers, the story wouldn't make sense. Kupperman knows how to keep his audience at bay when he needs to. It creates the same aura of mystery that his father enjoyed for much of his life.

Those looking for closure will likely not enjoy All the Answers. But for everyone else — for all the people who love books about complicated relationships between parents and children, like Fun Home or The Glass Castle, All the Answers is a balm. Though it's drawn in lines so big and clear that it could practically be a coloring book, Kupperman embraces fine details and nuance in his story.

This is the kind of book that will live in your head for years. You might just find, one bleary morning after too many dreams of dead relatives, that you look in the mirror while brushing your teeth only to see Kupperman's inexpressive cartoon eyes staring back at you. Those eyes might not smile or widen, but they can see everything.

Talking with the future of Seattle poetry about finding a voice in difficult times

S/o to @mosslitmag poets @troyosaki, @JasleenaGrewal, & @richsssmith in conversation about poetry/politics/regionalism with @paulconstant at this vol. 3 realease party. These people are so dope and so smart. Grateful for their voices 🙏🏽 pic.twitter.com/J8MjwgQAO2

— Dujie Tahat (@DujieTahat) June 14, 2018

Last month, I interviewed three poets as part of the launch party for the third issue of the Northwest literary magazine Moss. Seattle poet (and Stranger books and theater editor) Rich Smith had a lot of smart things to say about the political moment in poetry, but I was especially impressed with the two younger poets on the bill — Troy Osaki and Jasleena Grewal. Grewal is a brand-new poet who has only just started attending readings, and Osaki is a slam champion who is making the move into a more literary sphere. The stories of personal transformation through poetry that they shared with the audience felt inspirational.

"I went to law school," Osaki told me, because "I wanted to learn a skill to serve people in a tangible way." But he said "law can be really limiting," in that so much of it holds things "in place" so they "aren't necessarily transforming anything."

"But with art and poetry we can imagine new things, new ways of living, new worlds," Osaki argued. And so in this time when Donald Trump has ratcheted up political tension, everything is "really intense," and so many people are feeling powerless, they're turning to poetry.

"A lot of folks are looking for answers and new ways of thinking," Osaki said, "and they're turning to art to kind of grab onto those new worlds and try to expand our view of what could be. Intense times equals intense poetry."

I asked Grewal how she went from being an entirely inexperienced, unpublished poet to reading at a literary magazine launch party in less than a year. Her first published work appeared in former Washington state poet laureate Tod Marshall's anthology of local poets, WA 129. From there, she started reading with "my friends who are writers, and then I started submitting."

Grewal's theory is "I just go to whatever I'm invited to and wherever my friends are reading." She shows up to support her friends, "and then I'm talking to people and meeting people."

I asked these two poets at the beginning of their careers who they'd highlight if they were asked to choose the poets for the next issue of Moss. "When I think about a quintessential Northwest poet, I think about Sierra Nelson," Grewal said. "I studied poetry at Friday Harbor for awhile and she was one of the mentors and I learned a lot from her."

Osaki cited another Moss poet, Azura Tyabji, as someone he wanted to highlight. "She just became the Seattle Youth Poet Laureate a few weeks ago," he said. "She's incredible. And I think just in general, turning to young poets who are writing really awesome stuff around the city and greater Seattle" is important in times like these.

The only thing worse than fame is not being famous anymore

Published July 03, 2018, at 11:48am

Robin Williams was an American original, a comedian so alive that he seemed to radiate life. Can a new biography capture everything that made Williams so brilliant, while still remembering all the flaws that made him human?

Don't forget to join us on Thursday for the Reading Through It Book Club

This Thursday, July 5th at 7 pm, the Reading Through It Book Club will be gathering at Third Place Books in Seward Park to discuss David Grann's Killers of the Flower Moon, a true story about the 1920s incident that basically created the modern FBI.

If you're looking for a book to read over the 4th of July, this is the closest thing to a summer read that our book club has done yet — a true crime story about greed, murder, the relationship between indigenous peoples and white American settlers, and the end of the Wild West.

If you've already read the book, I hope you'll show up for the discussion. It should be fascinating. In a time when the president of the United States is actively undermining the FBI, we need more than ever to understand what the agency has been, what it was founded to do, and where we are today.

Chalice

(for the people of Flint, MI with empty cups and running faucets)Someone fed them

A story

Of Jesus turning water to wine

Here they heave

From their subsequent thirstLies wafer-thin as the body

Lead pours out as the bloodDo this in remembrance

Do this & remember it

Do this & dismember themAmen.

Fall and Winter sponsorship blocks are now live!

We’ve just released our sponsorship blocks for the last half of 2018, and the beginning of 2019.

Last year, the Fall and Winter schedule sold out in a few weeks, so we recommend acting fast. It’s first come, first serve, as always. One thing that makes this program special is that only one of you at a time gets the entire site to yourself. Your money helps us pay for our columnists, reviewers, and keeps the lights on (the pixels lit?). In return, you get exposure to the best book-loving audience Seattle has to offer.

Our sponsors are very creative, and use this space to advertise books, events, workshops, and even services for writers. If you’d like to reach this unique, intelligent, and engaged audience — or just want to know more about how this works — head on over to our sponsorship pages to read more, and see what dates are still available for you to book. We’re looking forward to hearing from you!

"The old throes of violence seem to have passed away"

"I had thought that history dealt with people who are dead and silent," says McCloskey, but when he began gathering quotes for A Glimpse into History, he found voices that still speak loudly today — with joy, with fury, with determination. The book he made allows those voices to speak again, even if indirectly, against the policies that threaten years of gains to protect our public lands. A leader in the conservation movement — executive director, then chairman, of the Sierra Club for three decades — McCloskey's book is both a celebration and a terrifying reminder of how long this fight has endured, and how ground once lost may be lost forever. Visit our sponsor page for .

Sponsors like Michael McCloskey make the Seattle Review of Books run. We're thrilled that the site was sponsor-supported for every week so far in 2018. To thank all those who made it possible, we're running a pre-sale on fall and winter slots for past sponsors, just through the end of the day. Email us at sponsor@seattlereviewofbooks.com to reserve your slots!

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from July 2nd - July 8th

Monday, July 2: Tonight I'm Someone Else Reading

Chelsea Hodson's book of essays touches on jobs she's held (including at NASA) and discusses the idea of submission and commodification in human interactions. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, July 3: the empty season Reading

Seattle poets EJ Koh, Sarah Galvin, Quenton Baker and Joshua Marie Wilkinson help poet Catherine Bresner debut her first collection of poetry into the world. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, July 4: Independence Day

Go watch stuff blow up and feel ashamed to be an American.Thursday, July 5: Nordic Stories

The beautiful new Nordic Museum's "storytelling-and-crafts program for preschool-aged children and their grown-ups" continues with a reading of the book Daisy Darling, Let's Go to the Beach by Markus Majaluoma. The author is not in attendance. This is a story time for kids. Nordic Museum, 2655 NW Market St, http://nordicmuseum.org/future, 10 am, free.Saturday, July 7: Poets in the Park 2018

See our Event of the Week for more details. Anderson Park, 7802 168th Ave NE, 11 am, http://www.graceguts.com/poets-in-the-park, free.Sunday, July 8: Mr. Neutron and The Songs We Hide Reading

Two authors who have taken writing classes on Whidbey Island, Joe Ponepinto and Connie Hampton Connally, read from their books. Mr. Neutron is about American politics. Hampton Connally's The Songs We Hide is about Budapest. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Poets in the Park

Redmond takes its poetry seriously. Like Seattle, they have a poet laureate program (the current Redmond Poet Laureate is Melanie Noel.) But unlike Seattle, Redmond hosts an all-day poetry festival in a city park every summer. You could make the case that Redmond is doing more for poetry as a civic art than any other city in Washington.

This Saturday, Redmond hosts the Poets in the Park celebration, an all-day hoo-hah of activities, readings, and poetry classes that is free to attend. Events include a bookmaking class for kids, poetry mini-golf, and places to create your own poetry themed art.

Readers at Poets in the Park include Washington Poet Laureate Claudia Castro Luna, Julene Tripp Weaver, and Jeannine Hall Gailey. Local organizations represented in the day's readings include Jack Straw Writers, the African-American Writers’ Alliance, and MoonPath Press. Classes include a tutorial on how to do a list poem and a nature walk that doubles as a poetry writing prompt.

Additionally, Redmond indie bookstore Brick and Mortar Books is hosting a book fair in which any poet can sell their books. Publishers like Chin Music Press will also be on hand, along with Poets & Writers and Rose Alley Press.

Seattle doesn't do anything like this. We really should. And we should look to Redmond as an example of how to do it.

Anderson Park, 7802 168th Ave NE, 11 am, http://www.graceguts.com/poets-in-the-park, free

The Sunday Post for July 1, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

A Cultural Vacuum in Trump’s White House

What I love about this bit by Dave Eggers is that it’s not just a potshot at the cultural ignorance of president who, god knows, deserves any potshots that land. Nope: It’s a thoughtful piece that deftly connects Donald Trump’s rejection of the arts to the authoritarian underpinnings of his philosophy. As Eggers notes, no president on either side of the aisle has carried this level of hostility toward intellectual and creative pursuits. This isn’t about political party, it’s about the icy dead space in the soul of an obscenely, mistakenly powerful man.

The White House is now virtually free of music. Never have we had a president not just indifferent to the arts, but actively oppositional to artists. Mr. Trump disparaged the play “Hamilton” and a few weeks later attacked Meryl Streep. He has said he does not have time to read books (“I read passages, I read areas, I read chapters”). Outside of recommending books by his acolytes, Mr. Trump has tweeted about only one work of literature since the beginning of his presidency: Michael Wolff’s “Fire and Fury.” It was not an endorsement.

In praise of (occasional) bad manners

Freya Johnston reviews, with great historical intelligence, Keith Thomas’s recently published The Pursuit of Civility. As well as an interesting tour of how politeness has evolved through centuries, her essay is a reflection on how manners are a language: an exchange, defined for a particular purpose by particular people, usually those with privilege to burn, and usually received by those without.

Courtesy, and the insistence on it, can be used to subjugate. By the same token, refusing a seat at one’s restaurant to someone whose political views are not just disagreeable but reprehensible may be rude — but the breach may also be a statement of humanity.

One theory of civility will tell you that it is all about acknowledging the separate existence, property, privacy and right to respect of another person. But another prevalent and persuasive theory of civility will insist that such codes of behaviour are all about subjugation: they are visited on people who must be brought to order rather than treated as equals. Thomas quotes the antiquarian Edmund Bolton (born around 1575), who announced that it was “no infelicity to the barbarous” to be “subdued by the more polite and noble”; after all, to possess “wild freedom” meant nothing compared with the gifts from above of “liberal arts and honourable manners.” It isn’t hard to imagine what the wild and free response to that might sound like.

Meet The 26-Year-Old James Beard Award Winner Reinventing Food Writing

Abigail Koffler’s profile of food writer Mayukh Sen, who just won a James Beard award for his own profile of soul food sensation Princess Pamela, is a delightful rabbithole of links. It’s also an interesting look at how even food writing has been politicized since 2016 — which honestly seems much needed when I look back at how many headlines after Calvin Trillin’s awful New Yorker blunder used phrases like “unpalatable for some.” “Some”? Time for some new voices to have their say.

The stories Sen wrote often hinge on experiences that set him apart from the rest of the staff. During a holiday brainstorm at Food52, an essay about fruitcake was floated, with the assumption that “fruitcake sucks.” Unlike the rest of the staff, Sen likes fruitcake. His dad grew up eating it in Calcutta, India and it’s part of the holidays. The dessert is a double edged sword: he’s also been called a fruitcake, a slur against gay people. His essay on the topic explored the usage of fruitcake as a pejorative and the popularity of fruitcake in India. Similarly, an essay about the queer history of kombucha shared the hidden story of a beverage now soaring in popularity.

Whatcha Reading, Chelsea Hodson?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Chelsea Hodson is the Brooklyn-based author of the book of essays Tonight I'm Someone Else, and the chapbook Pity the Animal. She'll be making a Seattle appearance this Monday, July 2nd, at the Elliott Bay Book Company, in conversation with Christopher Frizzelle. Personally, I would ask her about Mons Tua Vita Mea writing workshops she runs in Sezze Romano, Italy, because that looks like a dream come true.

What are you reading now?

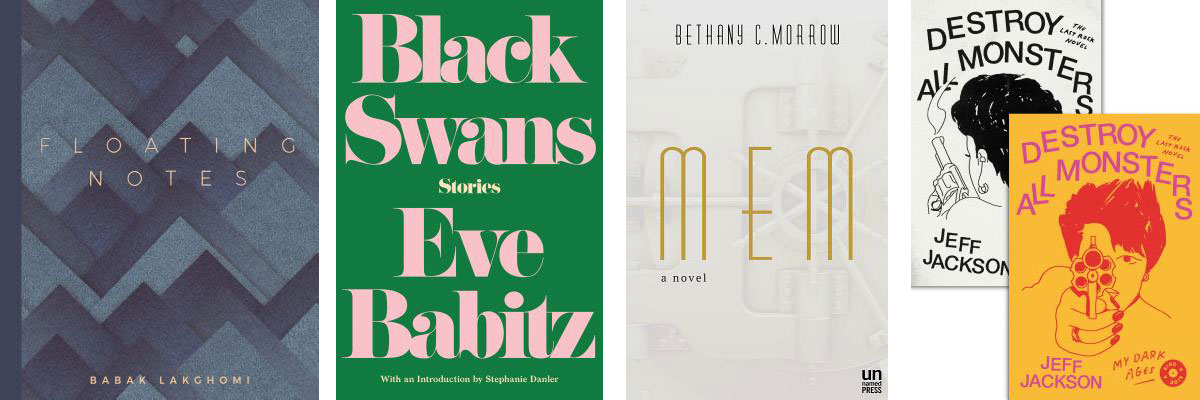

I just started reading an advanced review copy of Floating Notes by Babak Lakghomi, a novella which comes out soon from Tyrant Books. I really love seeing what writers can accomplish in books less than a hundred pages, so I look forward to finishing the book soon. The back cover copy says, "There are no clear answers, there are no solutions," which is right up my alley — these days I embrace ambiguity in art more than anything.

I'm also halfway through another Tyrant book — Vincent and Alice and Alice by Shane Jones, which won't be out until next year, and encompasses my favorite combination: laugh-out-loud funny and knife-in-your-heart sad.

What did you read last?

I've just finished Black Swans by Eve Babitz, one of my favorite writers. The first story opens with a page that says: "Jealousy — It's only temporary: you either die, or get better... Something we used to say about life in general, feeling sophisticated and amusing in bars, back in the days when we thought how you behaved was the fault of other people." I don't know how anyone could stop reading after a first page like that. There's a glamour to Eve Babitz's writing that I appreciate, and a kind of confidence that makes anything she writes sound like a universal truth.

What are you reading next?

I bought Bethany C Morrow's novel, MEM, after being really impressed by hearing her read from it in New York a few weeks ago. In this book, "Mems" are memories that have been extracted from one's own mind and manifested into a complete separate being. I really liked what I heard, so I'm excited to read more.

I also just received an advanced review copy of Destroy All Monsters by Jeff Jackson, which will be published later this year. Subtitled "The Last Rock Novel," this book has two sides — Side A and Side B — and can be read either side first. I've always admired Jeff Jackson's experiments, and I think this novel seems unlike anything else I've ever read, so I'm really looking forward to diving in.

The Help Desk: How do book-minded Seattleites push back against Amazon?

Cienna Madrid is on vacation. This Help Desk was originally published on November 6th, 2015. But you can still send in your questions! Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I can't remember if my anger and frustration with Amazon began when I heard about the "gazelle" project, or when I heard about their total lack of philanthropic investment in our city, or what, but by the time the Hachette e-book price wars started up, my rage had reached a boiling point, and with the opening of their stupid bookstore, I am just seething. I hate what they've done to books and book publishing and everything I hold dear as a writer, editor, and reader. So my question is: how best to channel my rage? I already stopped shopping there, and I think my friends and family are honestly pretty sick of my virtual and in-person ranting on the subject. I need some new ideas for creative or constructive outlets for my Amazon hatred. Help!

Marybeth, Ravenna

P.S. I am a pacifist so violent direct action is not an option.

Dear Marybeth,

I understand your feelings of impotence and frustration. It would be melodramatic to say that Amazon ruined the publishing industry, the book selling industry, or Seattle. However, it's fair to say that Amazon waited until publishers, booksellers, and the city of Seattle as a whole was sleeping, took a big smelly dump on their chests and said, "you look like shit but that's not my problem."

A better advice columnist might tell you to take the high road and ignore their crappy business dealings but I'm afraid of heights so the high road is never an option for me. So what do you do? I suggest working to change the only item on your above list that you have a kitten's chance in hell of influencing: Amazon's philanthropic giving, which is laughable. It amazes me that with 24,000 employees in Washington state alone, and many of them Seattleites, those employees aren't demanding better from their employer. Instead of instigating poster wars that attempt to shame Amazon tech bros for moving to Seattle and "ruining" neighborhoods, why aren't Seattleites banding together to demand Amazon be a better philanthropic presence in the city that has contributed greatly to its success?

There are enough readers, writers, booksellers, sympathetic Amazon employees, and liberals in Seattle to put pressure on that company to change its corporate structure in one small way. How to accomplish that exactly, I can't say. Someone who's well versed in organizing, rather than telling alcoholic librarians what to do every Friday, should come up with a plan. (The only protest I can claim participation in took place last Christmas when, after a bathtub's worth of hot buttered rums and gin! Gin! Gin! my liver went on strike.)

Affecting change in that way, I believe, would make a satisfying difference.

(If it doesn't, you could always try taking a dump in front of their store. That also makes a satisfying difference.)

Kisses,

Cienna

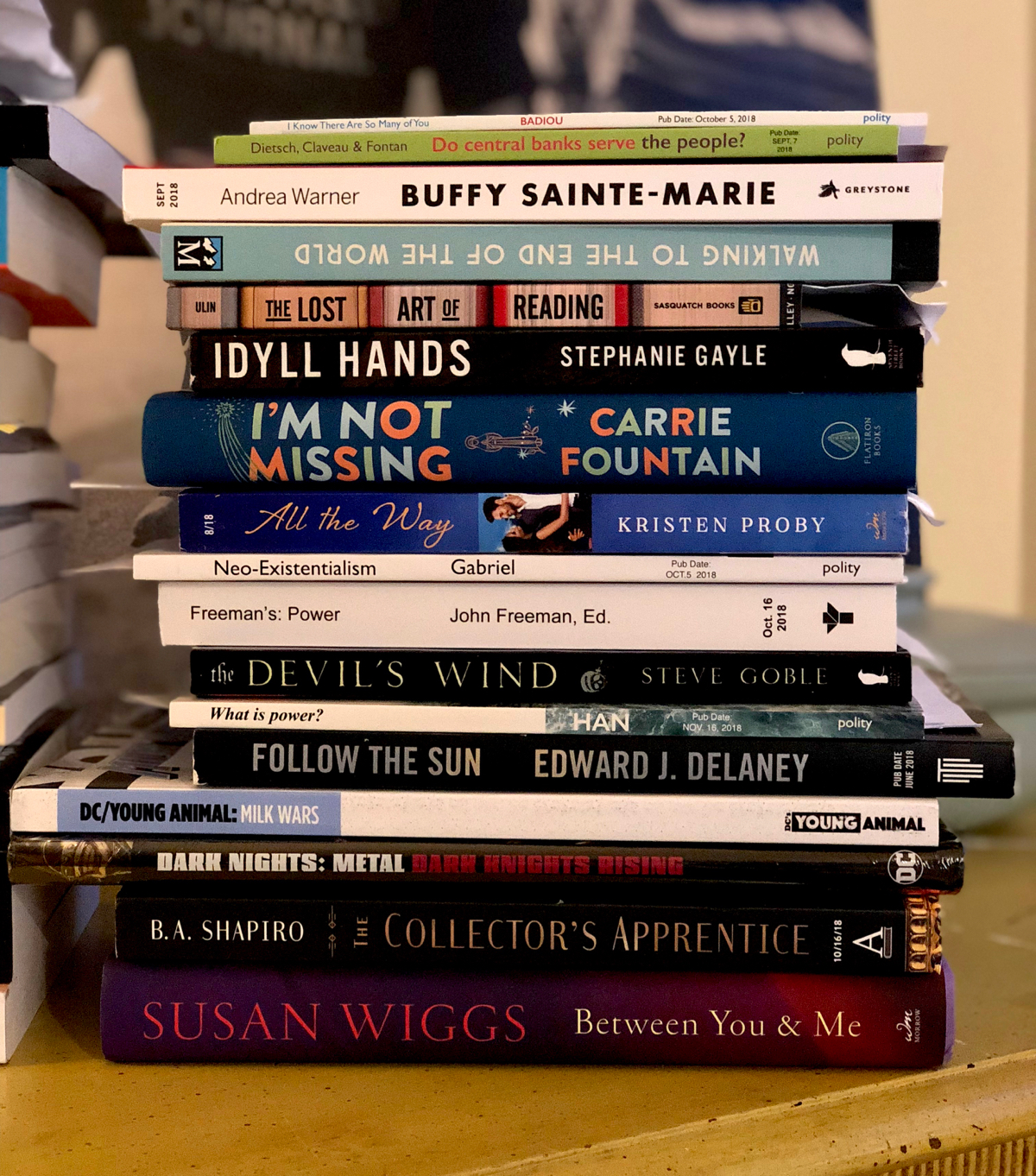

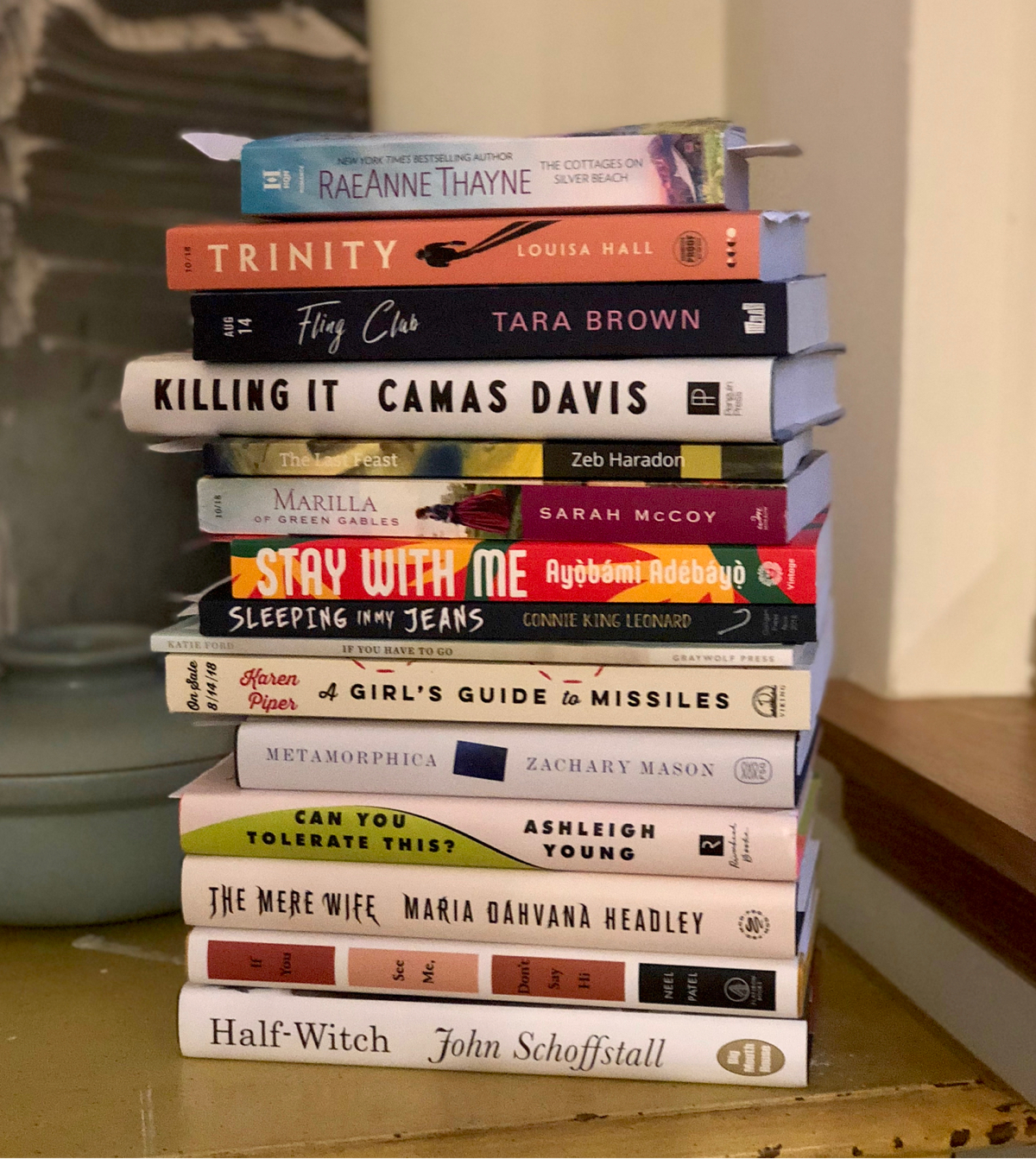

Mail Call for June 28, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Portrait Gallery: Summer Storm

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

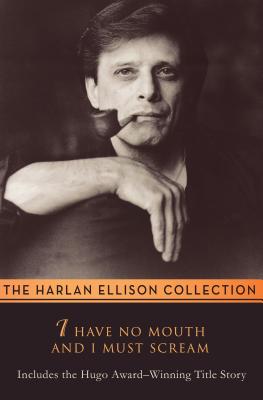

Harlan Ellison, 1934-2018

Sad news about one of sci-fi's biggest and brashest personalities:

Susan Ellison has asked me to announce the passing of writer Harlan Ellison, in his sleep, earlier today. “For a brief time I was here, and for a brief time, I mattered.”—HE, 1934-2018. Arrangements for a celebration of his life are pending.

— Christine Valada (@mcvalada) June 28, 2018

Ellison was what people politely call "a writer's writer," which is to say his books didn't sell in huge numbers, but he was hugely influential for other writers. Stephen King and Neal Gaiman have both praised Ellison hugely and publicly. If you'd like to read more about Ellison, here are a few suggested recent pieces:

If you're looking to read something by Ellison, I recommend you try I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream to get a taste of his fiction, and The Glass Teat for some of his cultural criticism. I can honestly say that there will never be another author like him.

Criminal Fiction: Sunny noir

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page

Reading around: new titles on the crime fiction scene

Mike and Verity indulge in an intoxicating game they call the Crave, in Araminta Hall’s Our Kind of Cruelty (Farrar, Straus & Giroux): Verity flirts publicly with an unsuspecting target and, at the designated moment, Mike comes to her rescue. Then the two of them furtively — or not so furtively — satiate their mutual passion. Obsession, manipulation, dark twists, and toxic violence mark this highly-readable psychological thriller, in which one of the twists is inextricably tangled in the narrator’s voice: the story is told by Mark, from his perspective, and the result up until the very end is downright chilling, as well as alarming on multiple levels.

There’s nothing like a child gone missing from a party to put a damper on things, which is how Cara Hunter’s Close to Home (Penguin) opens. But as the police investigation kicks off, things get infinitely more complicated. Hunter’s deep dive into the disturbed psyches embedded in our societies is gripping, and the smooth and engaged writing here will keep your nose well-tucked in this book. That, and that fact that what constitutes the mystery at the heart of the novel keeps jumping around like multiple mad red herrings in a barrel.

The Hellfire Club by Jake Tapper (Little, Brown) is both an engaging and slyly timely foray into Washington politics. Set in the 1950s, with cameos by such figures as Roy Cohn, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and Dwight Eisenhower, this political thriller sees Charlie Marder, a war veteran and a Manhattan-based academic, thrust into a congressional seat due to a previous congressman’s untimely death. As Charlie and his astute wife, Margaret, wend their way across Capitol Hill and cocktail parties, Tapper’s fiction debut incorporates shades of Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington as well as elements of contemporary toxic alliances.

After last year’s wonderfully entertaining Magpie Murders, Anthony Horowitz has re-tuned his ultra-dexterous writing hand once again with The Word is Murder, (Harper), featuring, well, Anthony Horowitz. Having penned two Sherlock Holmes novels in real life – Moriarty and The House of Silk — Horowitz here plays a Watson-like role as semi-second fiddle to a private detective, Daniel Hawthorne, in contemporary London: he agrees to author the detective’s case in the true-crime category. It’s a doozy of a case from the get-go just on its own — a woman walks into a funeral parlor, plans her funeral, six hours later she’s been murdered. But the mystery is also chock-full of smoothly-written set-pieces, some mind-bendingly straight out of the real-life Horowitz’ worky and personal adventures and misadventures. Ace.

The Quintessential Interview: Spencer Kope

Spencer Kope’s FBI tracking star Magnus Craig can perceive people’s “shine” or aura, a color-infused trail akin to a giant fingerprint. In Whispers of the Dead (Minotaur), pairs of human feet keep turning up like bad pennies as Craig and his partner Jimmy Donovan chase a killer across Louisiana, Arizona, and Texas. Apart from his special perception powers, Craig has a way with words, an affinity for Bernard Minier novels, and, like Kope, collects first-edition books. Kope, a crime analyst as well as a writer, lives in Washington State.

What or who are your top five writing inspirations?

To answer this, I have to go back to a time when computer screens were small and monochrome, and processing speeds were measured in kilobytes, because it was the early eighties when I discovered the macabre but fascinating world of Stephen King.

I began with Skeleton Crew and Night Shift, after which I was hooked and devoured everything I could find: short stories, novellas, books, things he scrawled on napkins….Okay, I made that last part up, but you get the point. Of all the King stories I read, The Stand remains my favorite. I even liked the miniseries.

Other writers who inspire me are those who persevered: Richard Adams and his opus Watership Down come to mind. The book was repeatedly rejected before being picked up by a one-man publishing house in London; the rest is literary history. Vince Flynn is another example. He self-published his debut, Term Limits, and went on to launch the incredibly successful Mitch Rapp thriller series. Among my collection of first editions are two signed copies of this rare book.

Top five places to write?

I’ve written while aboard a nuclear-powered fast attack submarine, next to a hotel pool in the Canary Islands, at a quiet spot on the Black Sea, and at Starbucks coffee shops in several cities, but the place I’m most productive and least distracted is in my study. It’s not a grand space, but my Lord of the Rings swords are ensconced upon the wall, opposite my eight-foot storyboard for working plots and characters.

Top five favorite authors?

Such an easy question shouldn’t be so hard to answer. If I really have to choose only five, I’ll have to go with Michael Crichton, Erik Larson, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and J.K. Rowling.

Top five tunes to write to?

I can’t listen to music with lyrics for fear that my antagonist will suddenly break into song. And since a serial killer singing some twisted version of Welcome to the Jungle is not what my fans are looking for, I stick to instrumentals.

I have a playlist specifically for writing, and some of my favorites are Boadicea, by Enya, Terra Firma, Wisdom, and Eternal Odyssey, all by Delerium, and Adiemus by Karl Jenkins.

Top five hometown spots?

The Lynden Starbucks has to be on this list simply because they make me feel like Norm from Cheers whenever I walk in. Larrabee State Park, which is along Chuckanut Drive, is my favorite park, both for the drive that takes you there and the scenery once you arrive (plus I like standing in the tunnel under the tracks when the trains roll through). Village Books in Fairhaven and the newer store in Lynden are near the top of my list. Sadly, Michael’s Books, which was packed to bursting with used books, shut down a few years ago, otherwise it would make the cut. Rounding off the list is Front Street through downtown Lynden for its quaint small-town feel and Edaleen’s Dairy, where you can get massive amounts of ice cream stuffed into waffle cones.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The death of Kill or Be Killed

If you just glance at him, Dylan — the main character of Kill or Be Killed — looks like a classic comic protagonist, a brown-haired generic white guy like Peter Parker. But Sean Phillips is a subtle artist, and at certain angles Dylan's presentation falls apart. His bangs just hang limply in his face. His mouth falls open and he stands slack-jawed a lot. His posture is bad.

Ed Brubaker, the writer of Kill or Be Killed, said that the series is intended in part as an homage to 1970s Spider-Man comics, and the cover of issue #20, which was published yesterday, is a direct tribute to one of the most famous Spider-Man covers of all time. But the series isn't about a superhero: Dylan is a spree killer, an unhinged vigilante who, at the behest of a demon who may or may not be real, murders anyone he deems as guilty. We don't know how much of the story is real, or how much we should trust Dylan. In practice, Kill or Be Killed is a closer relation to Taxi Driver than to any Marvel Comic.

This twentieth issue marks the end of (at least this iteration of) Kill or Be Killed, and the book is definitely worth picking up in a collected edition. This is, far and away, my favorite of Phillps and Brubaker's many collaborations — a riveting cross between Notes from Underground and The Punisher. (Come to think of it, the misanthropic star of Dostoyevsky's novella could just as easily have gone vigilante himself: "I am a sick man. I am a spiteful man. Criminals are a cowardly and superstitious lot.")

Kill or Be Killed arrives at just the right time: fandom has, like the rest of the country, grown unhinged and entitled. They're having a hard time drawing a distinction between themselves and the heroes they admire. Dylan is, in many ways, a reflection of that self-regard: obsessed with a sci-fi/fantasy painting of his father's, Dylan decides he alone is the arbiter of the difference between right and wrong. He loathes all institutions and believes that justice is best delivered with extreme prejudice.

I can't say much about the last issue of Kill or Be Killed without ruining the story, but I can tell you that it is satisfying, in much the same way that the rest of the series is satisfying. It curves around your expectations and furiously resists any easy answers. Just when you think you've gotten your hands around the book, it slithers out of your grasp and starts nipping at your heels again.

Book News Roundup: Third Place Books customers raise nearly $7500 for RAICES

- Oh for the love of God let's start with some good news. Last week, Third Place Books announced that they'd donate 20 percent of all sales to reuinite families at the border. That went really, really well:

A huge thanks to all the readers who came out on Saturday to support our fundraiser.

— Third Place Books (@ThirdPlaceBooks) June 27, 2018

On behalf of our customers, we are sending $7,488.00 to @RAICESTEXAS !

If you want to contribute directly, you can do so here : https://t.co/DddGnETNvM pic.twitter.com/wf8Az8ivZg

Last weekend, Seattle's newest comic book convention, the Ace Comic Con, happened in SoDo. The Beat's Joe Grunenwald reports on how it went. Sounds like the show was more pop-culture focused than Emerald City Comicon, but it was still fun, though there were some scheduling SNAFUs with big panels featuring actors from the Marvel movies.

Why is Tao Lin's new book Trip on bestseller lists? Does the literary world have a collective amnesia problem? Jakob Maier at BuzzFeed points out that Lin has a problematic past.

Readers new to Tao Lin’s work (he has previously published three novels, two collections of poetry, one book of short stories, one novella, and a volume of selected tweets) might not be aware that the success of Trip could be considered an example of the kind of comeback story we might get accustomed to if we don’t hold to account the men accused of abuse or harassment during the #MeToo movement... I’m thinking especially about Tao Lin’s seemingly easy and uncontested return, after he was accused in 2014 of statutory rape, emotional abuse, and plagiarism.

- This is nice:

Before @google, people would ask librarians very interesting questions.

— Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) June 24, 2018

—New York Public Library @nypl pic.twitter.com/4fVKG0qJI6

- The Association for Library Service to Children changed the name of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award to the Children’s Literature Legacy Award. The ALSC argued that Ingalls Wilder's work contains "expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with ALSC’s core values of inclusiveness, integrity and respect, and responsiveness." Of course people in comments have lots of opinions about this. WE ARE ERASING HISTORY, they bellow. (Not true. History is still there. I checked.) They cry, WHO WILL WE SILENCE NEXT? (Tao Lin, hopefully.) They shout SO MUCH FOR THE TOLERANT LEFT! (Tolerance hasn't done us much good so far.) You can whine about freedom of speech all you want, but the fact is that the ALSC is a private organization, and if they don't want to give an award in the name of an author who does not meet their modern standards, that's perfectly fine. If your organization wants to give out the Adolf Hitler Award for Excellent Customer Service, that's your right. It would be my right to organize protests against your idiotically named customer service award. See? That's how America works!