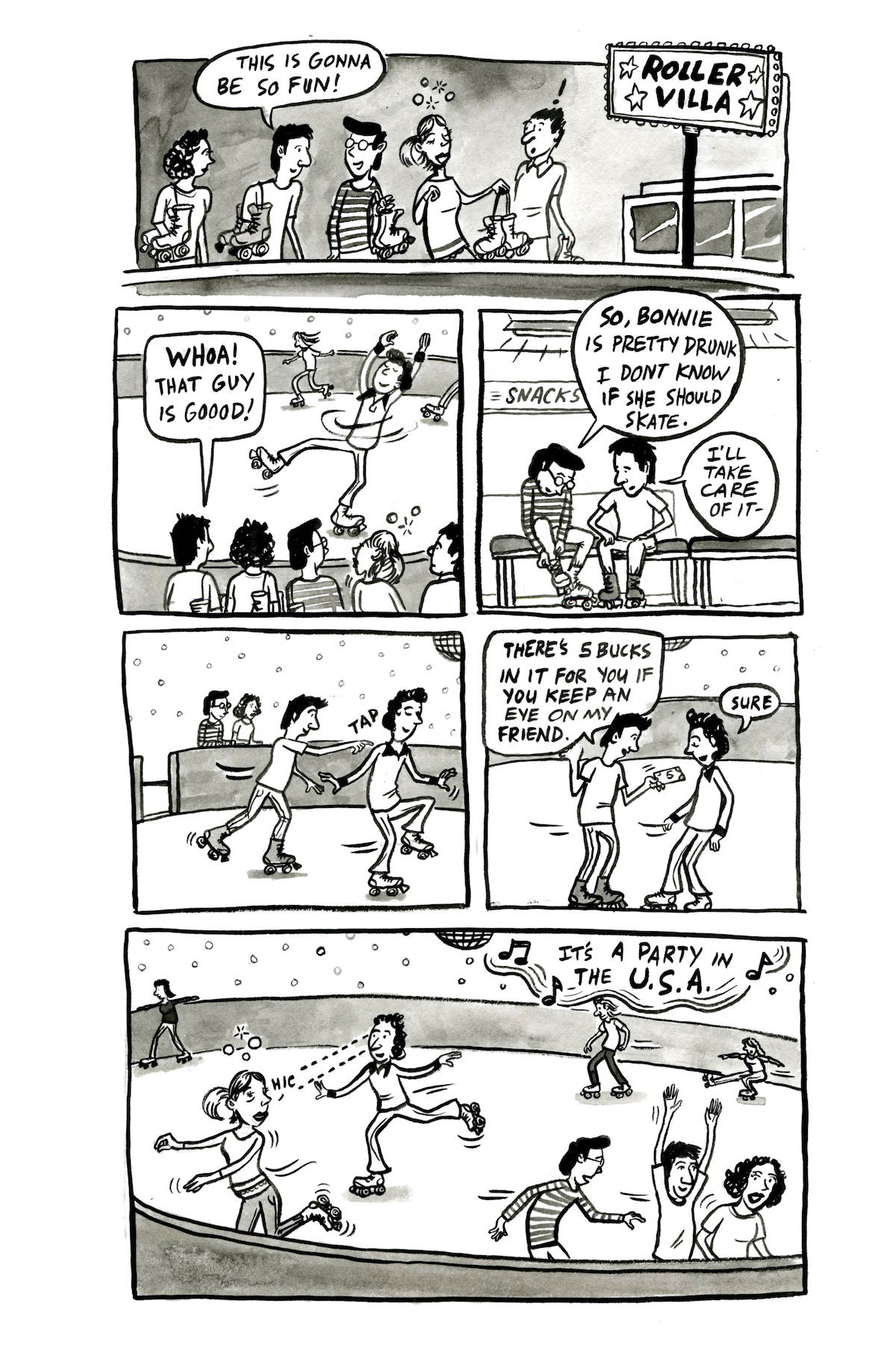

Thursday Comics Hangover: Milk is hell

I've been enjoying the Young Animal line of comics curated by My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way. They're a pop-up imprint published on the fringes of the DC Comics superhero properties, taking on the same rebellious-goth-teen role that Vertigo Comics did back in the 1990s. The best Young Animal books, like Mother Panic, fill in a gap left by the all-ages edict of mainstays like Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman. They're a little bit weirder, a little bit more imaginative, a lot looser.

This week saw the first issue of Milk Wars, a crossover between Young Animal comics and DC Comics. If you've ever been disgusted with the crass action-figure ballet that is the typical superhero crossover, you'll probably find something to love here.

Milk Wars is a meta-crossover pitting the weird heroes of the Doom Patrol versus the staid, conservative heroes of the DC Universe. And thanks to an intergalactic bureaucracy called Retconn, the DC Universe has been made even more conservative. Superman is a flying milkman. The other Justice League figures have been recast as the Community League of Rhode Island, a staid suburban homeowners association with superpowers.

This feels like a crossover with something to say, which is a rarity for the genre. Of course, some of that conservatism of the mainstream DC line rubs off on the Doom Patrol; while the Young Animal books are generally content to be weird without bragging about how weird they are, in this comic they're painfully self-aware.

"Some of the best people are weirdos," a Doom Patrol member says while in the middle of a fight with the godlike milkman, and the point is made. But then two panels later, she adds, "everyone's a little strange, and that's okay." Later on, someone says "maybe strange deserves a shot." There's nothing less weird than talking about how weird you are; the repetition gives off the impression of a coffee cup that reads "You Don't Have to Be Crazy to Work Here, But It Helps!"

This is probably the reason Vertigo began enforcing a concrete divider between itself and the mainstream DC superhero universe in the late 1990s. When you combine the two tones into a single book, you get something that feels a little smaller than its component parts. Milk Wars, at least, seems to recognize that flaw and builds it into the plot.

And in Milk Wars #1, you get several full-page shots of people with bizarre powers punching each other, which is the point of these whole things, right? Can there be anything more dull, anything more in direct opposition to art, than conflict for conflict's sake? And isn't there maybe a chance for some art to made out of that artlenssness?

This weekend, come learn about literary careers. In two weeks, come watch Fran Lebowitz run intellectual circles around me.

I'm taking part in a pair of upcoming events that you should know about:

- This Saturday, February 3rd, I'll be on a panel at Literary Career Day at the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library. This is a free event intended to offer information and encouragement to young people aged 16 - 24 who are interested in pursuing careers in the literary arts. It runs from 11 am to 4 pm, and you can register here. A description, from SPL's website:

This event will start with Keynote Speakers, followed by lunch—free for all attendees—and a Table Fair featuring opportunities from local arts organizations. After lunch, attend the Breakout Session that's relevant to your interests. We'll finish off the afternoon with a Networking Party, featuring a live DJ, to help you get the most out of your Career Day!

- I'm interviewing Fran Lebowitz at Benaroya Hall on Sunday, February 18th. Lebowitz possesses a remarkable wit — she's a natural heir to Dorothy Parker, Oscar Wilde, and other historical wiseasses. It's intimidating as hell to share a stage with her, and I'll certainly feel better if you're there to back me up. You should read this interview from the last time Lebowitz came to town that was conducted by my friend Bethany Jean Clement to get an idea of what I'm up against. This is terrifying for me, which means it should be fun, at the very least, to watch me squirm. Hell, I can guarantee that it will be entertaining to watch me get my clock cleaned by one of the funniest people alive.

Too complicated to feel

Published January 31, 2018, at 12:00pm

Alex Blum came out of the Army Rangers broken — so badly broken he mistook robbing a bank for a training exercise. His cousin wrote a book about the fracture lines running through them both.

A story for another time

Is Amazon very good or very bad at naming things? It's honestly hard to tell. Why would any company choose to promote a line of e-reading devices with fire-themed names, for instance? Most businesses would balk at the idea of even hinting at book-burning in their book-related products, but Amazon led with the Kindle and then doubled-down on the concept with its Fire family of tablets. Naming their personal-assistant line of speakers the Echo, too, seems a little cute — what is an echo but a hollow and fading repetition of ourselves?

But Amazon has sold hundreds of thousands of those devices, and so by the only arbiter that matters to Amazon — that of the market — the names must be considered a success. The problem with this thinking, of course, is that markets can only ignorantly choose winners or losers in the moment. There's no nuance to a market. If you make a mistake, but that mistake is rewarded with profits, you'll keep on making that same mistake until something catastrophic happens.

Earlier this week, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos unveiled the Spheres to the world. Located at the corner of 6th and Lenora downtown, Amazon's Spheres are a cross between a biodome and a corporate conference room. They're supposedly a place for Amazon employees to work in a pleasant natural environment. The Spheres have already become a symbol of Amazon's domination of downtown Seattle, and local media went positively berserk when Bezos took the press on a tour of the constructs.

Now, Amazon has opened up a public-facing section of the Spheres, and they've given it one of their trademark curious names: The Spheres Discovery at Understory. On Tuesday, Understory opened to members of the public who had the foresight to make reservations in advance online.

When walking into the Understory at the base of the Spheres, visitors are greeted by enthusiastic young people in bright Amazon polo shirts. They scan tickets and usher people inside with the barely restrained zeal of Scientologists. The first thing you'll see in the Understory is a wide array of video screens showing some of the plant life in the Spheres. One of the Amazon employees directs a tourist to stand in a colorful spotlight in front of a video screen. While standing in the spotlight, a narration to the video screens is audible — it sounds as though a tour guide is standing directly behind you, whispering information into your ear. Step an inch out of the spotlight and the voice is gone. Step back into the spotlight and she's there again.

In a room to the right of the video screens, visitors will find samples of plants that can be found in the Spheres above, including a particularly robust orchid. In a room to the left of the video screens, visitors huddle around some signage giving an ebullient explanation of the purpose that the Spheres serve in Amazon's corporate culture.

In this room, you'll see some testaments to Amazon's charitable giving. (Amazon gives much less than other corporate giants in the region, of course, but you won't learn that fact here.) Perhaps the most bizarre touch in this room is a spray of plastic bananas intended to promote Amazon's Community Banana Stand, which hands out free bananas in South Lake Union during the week. The bananas are obviously synthetic — they practically glow — and next to all the testaments of the Sphere's natural beauty they feel decidedly off-brand.

After exploring the three rooms, visitors are likely to start looking around for a way to climb up into the Spheres and explore the terrariums. That's when they'll realize the limits of the Understory. One tourist asks an Amazon employee whether the tour extends up into the Spheres. "No," the employee says. "They're actually working up there, so we can't interrupt them. You need a badge to get up there." The tourist nods, and then wanders over to the video screens to take a picture of a video tour of the inside of the Spheres. That's as close as he's going to get to the Edenic garden promised from the outside of the Spheres: a picture of a picture on a screen.

So. What is an Understory? It's basically the carpet of the forest, that spongy layer of green that absorbs and distributes water for everything else. But Amazon loves names with multiple, even contradictory meanings. It could be a fancy way of saying "basement," after all, and the Understory visitor center is the Sphere's cellar, basically. But "understory" also sounds like the parts of a story that a narrative doesn't explore: the innocent bystanders of fiction, the passersby who walk onto the page, say one line, and are gone. The soldiers who die messily in the background while the protagonists bask in glory. The screaming woman falling from a building who is saved at the last minute by Superman before she's desposited safely on the ground to wander into obscurity again. The understory is everywhere that the narrator doesn't direct our attention.

The reality of the Spheres is that if you have an Amazon badge, you're allowed into the story of the corporation. You get to hang out in treehouses and write code surrounded by exotic plants. If you don't have an Amazon badge, you're cast into the Understory. You wander around a rinky-dink museum with one exhibit that enthuses about what it's like to be allowed into the world above. You crane your neck and peer at the ceiling, and you wonder what it's like up there, in what you're told is the only story that really matters in Seattle right now. And then you'll realize you're never getting up there. And so you return, dissatisfied, to your story — to the understory.

Once you leave the Understory, you'll probably wander around the Spheres, trying to look inside. You'll walk by the tiny dog park, and by all the people bustling around with orange Amazon Go tote bags. You'll walk in that direction for a half-block, and you'll walk by the long line of people who are waiting in line to get into a cashierless convenience store that's plastered with signs promising you'll never have to wait in line again. None of it will make sense to you, but you'll just shrug and keep walking away from the Spheres. It's okay that it doesn't make sense to you. It's not your story.

Talking with Lisa Rosenblum, the new Director of the King County Library System

Earlier this month, Lisa Rosenblum had her first day on the job as the King County Library System Director. Rosenblum has worked in libraries across the country, but she’s taking the helm of an especially vibrant library system in KCLS.

King County Library System seems well-positioned for the future. Last year, digital reading platform Overdrive announced that King County led the nation in digital book checkouts, ahead of the systems for Los Angeles, New York, and even Seattle. In 2017, KCLS users checked out over four and a half million ebooks and digital audiobooks, but physical media hasn’t been left behind in the digital gold rush—over ten million visitors checked in to KCLS’s 49 branches, and they checked out some sixteen million non-digital-book items.

We talked on the phone with Rosenblum last week, to get a sense of where she’s from and what she wants to do at KCLS. The following transcript has been lightly edited.

What brought you into this line of work, and how you came to be interested in libraries? Do you have a librarian superhero origin story?

Well, I know you’re hoping for a romantic story, but I'm afraid mine came from a recession. I went to this fancy liberal arts school back east, called St. John's College, which is a great book school that gives you a liberal arts education in the most traditional sense — you study Ancient Greek, and you translate Sophocles, and you read the plays in the original language. It was an amazing education. But I got out during a time where there were no jobs, especially for overeducated liberal arts majors.

So, I started working. I got a job at a government contractor that provided library services to Army libraries. This was outside of Washington DC. Then, from there, I moved to Houston, married my husband, and got a job at Rice University, doing what we called, back then, cataloging. I knew from that point on that I never wanted to be a cataloger, because we had to file cards. I don't know how old you are, but I’m old enough to remember cards and card files.

Oh, sure. Yeah.

So, the big deal was, if you were good, you could drop your own cards. You know the little rods that went through the holes in the cards?

Yeah.

Well, when you did it correctly, you were allowed to pull out the little pole, have the cards drop down, and then the pole went through the hole in the bottom of the card, and that was it.

At Rice University, you were only allowed to do that if you never made a mistake filing. Well, in two years working there, I never could figure it out. I always had one or two mistakes, so I was never able to drop my own cards. So, long story short, I knew that this level of detail work was not my strong point.

So, fast-forward: we leave Houston, we're in California. Back then, California was hiring librarians without library degrees if they took tests, and I said, 'I'll never pass.' My husband encourages me: 'Oh, just take the test. Take the test.' So, I did, and I failed miserably on anything librarian-ish. But remember I told you I had that fancy liberal arts education? Well, I could match the author with the title of all these old Greek and Latin and Roman works, so I passed the test. Then I had an interview, and I got the job as a librarian.

I really loved it in the public library. This was before the internet. I really enjoyed helping people find answers, find information. This is back when these big reference books were behind us, and we could pull them down and find the answers to questions like, what was the average temperature in Prague in August? You just felt so empowered. I also was a youth librarian, and I did book talks. I'd go out to schools and talk about books in a very entertaining way, summarize them very dramatically.

So, I really learned to love the public library, and that's kind of how I got into it. It wasn't like I woke up one day and said, ‘I want to be a librarian.’ It wasn't that I met a librarian when I was in high school or when I was in elementary school and she made an impact. In fact, back then, librarians, I thought, were kind of mean. And they also would separate the children's areas from the adult's, so if you were a kid you were kind of isolated from things.

That's really how I got to be a librarian. From there, I progressively started to enjoy what I was doing. I worked for a big system, did basically everything in it, and then decided I wanted to be a director. I got a couple of different jobs as a director — including the last one as the director of the Brooklyn Public Library. Every time, I just really enjoyed what we do in our communities. I think that we really are very impactful and have done a great job in changing with what our community needs. The library I entered into more than 25 years ago is different than the one that we run now, but it's still the same. We still value books and reading and literacy, but we just do it in a different way, that's all.

So you mentioned Washington DC and Houston and California. Where are you from originally?

I originally was born in New Jersey, on the East Coast. Then, when I was 12, we moved to Virginia because my dad got a new job. Then, like the pioneers, I gradually made my way out west. I lived in California for most of my career, but I took up the opportunity to work for Brooklyn, because they recruited me.

So, I did that for two and a half years, and I decided that as much as I like New York, I'm a West Coast girl now.

And, of course, the King County Library System is known nationally as one of the best in the country.

I wanted to ask you what drew you to apply for the job at King County.

Well, first of all, King County has a national reputation of public support for libraries, and building beautiful libraries, and being really innovative. We were hearing about King County in California 20 years ago, when Bill Ptacek, the beloved leader of KCLS, had the insight to realize we were in the materials movement business. He knew we needed — this is back before digital — to be more efficient in how we move our materials around our system, and created that huge sorting machine in Preston. They've always been ahead of their time, and the community support for libraries is very desirable.

Plus, living here, this is a wonderful place. Or so I’ve heard. Because I've come at the worst of times, I'm told. It's dark when I go to work, it's dark when I leave. So I'm told this is a beautiful area, I just have to wait a couple of months.

Fortunately, I moved here from Brooklyn and not California. I think the change from California would have been too much for me, but I left in a blizzard from Brooklyn, so I’m used to variations in weather.

What are you reading right now?

Well, right now, I'm reading the classifieds to see where I can buy a condo here. I have to be honest with you, I have not been reading a lot since I moved here a week and a half ago. But, the last book I read was Manhattan Beach [by Jennifer Egan]. In Brooklyn, one of our libraries was in Manhattan Beach.

I am very interested in reading regionally. I can't tell you what my favorite Seattle regional authors are, I'll be honest with you, but I'm looking forward to discovering them. The other nice thing about moving from Brooklyn to here is that New York City, in general, is a big reading community, and Seattle is too. So, it's great to go from one place to the other. People really like to read here.Do you have people putting together a list of King County authors to check out, now that you're here?

Well, you know, I haven't asked them to do that. I've asked them to create a map of where all my libraries are. I'm starting there. But that's really a great idea.

I’ll be a patron and ask for a list of the 10 best books I should start reading to learn about Seattle.

Oh, man. If you'd like to come back and share that experience, I would love to talk to you about that, too. That sounds great. I know you haven't been to all of the libraries yet, are there any of the libraries that you think are especially nice in the King County region?

It's like asking who's my favorite child. Let me just say this: I'm very interested in the Skykomish library, the one that I can't get to in the winter.

I'm interested in that one because, first of all, it's in a beautiful area of the state, but, also, it really represents how important a rural library is to a community. It's got limited hours, but it's important that it's out there, that it's open for people. So, that's sort of my adventure library.

Okay.

I'm starting to visit libraries this week. We're putting in a new maker space area in Bellevue, so that's going to be fun to go to in the next couple of weeks. We're basically creating a space where teens can create things. There'll be laser printers, and there'll be maker machines, and all sorts of stuff.

Oh, and I want to go to Vashon because I think it's so cool I have to take a ferry to get to one of my libraries.

So, yes, I'm looking forward to those, but those are kind of the cool adventure libraries. But, in general, I can't pick a favorite because the design of our libraries here is really amazing. Just the light — the recognition that it gets dark [in this part of the world] and just having all the light, even under the shelving, so that everything is so bright when you come in. It's very thoughtful. Our voters supported us to build new libraries and to renovate the existing ones, and I think we gave them a good bang for the buck here.

Do you have any priorities for your first few months at King County other than visiting the libraries?

Visiting, certainly. As I visit, I’ll be meeting with the staff. Also learning about the board, and working with the board.

And, of course, it's all about the budget — understanding the budget process, and really looking at the budget. How do we spend our money? What could we be doing differently? Just all the sort of basic stuff you do when you start a job.

I also said to the staff today, ‘when I'm visiting your libraries, I want the full King County experience. So where are the best coffee shops, the bakeries near where you are? Where would you go to lunch?’ I love to learn about the neighborhoods where our libraries are too, because they're all very different.

It just occurred to me that the Literary Lions fundraiser for the King County Library System Foundation is coming up in March. Are you going to be at that? Can people meet you there, if they attend the dinner?

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I need to find a dress for that.

What have you learned in your meetings with the staff? You have some great librarians out there in the King County system — I know from experience. Is there anything that the staff has really impressed you with, or is there anything that you learned that surprised you?

Well, first of all, I think our librarians are wonderful, but I also think our support staff — the people behind them, the people that are on the floor, that aren't librarians, our circulation people — are great. I think what impresses me is their service philosophy. They really love working with the public and serving them in the way they need to, and in a changing way.

I had a meeting this morning with staff that is very interested in how we're serving our diverse communities. They're interested in social equity. They really keep abreast on what's current in the library field, and what makes the most sense here. They're passionate about what they do. They're very, very passionate about their love of the profession and serving the public.

Ave Marías

Published January 30, 2018, at 1:03pm

Washington State Poet Laureate Claudia Castro Luna reads tomorrow night at Seattle Public Library at 7 pm. Her latest book memorializes women who were murdered in Juarez Mexico.

Remembering Ursula K. Le Guin

I met Ursula Le Guin in Atlanta. I was 31. Ammonite, my first novel, had been accepted for publication as a cheap mass-market paperback and I was trying to figure out how to get it some attention. So I went to Ursula's reading and book signing at a local bookshop and afterwards joined the line that inched closer and closer to her table, clutching one of her books.

Even then I knew that asking a writer on tour to read your book was a bad idea, but also knew that if you don't ask, you don't get. This was before email, before social media, before you could reach out via someone's website; it might be my only chance. There would be no time to articulate how I felt about her work, no opportunity to explain how important it was to me that she was here, that she might read something I had written, something that could not have existed without her and writers like Joanna Russ and Vonda McIntyre, Suzy Charnas and Octavia Butler, who were the latest in a long, long tradition of women levering out the bricks of the wall built to keep us out of the genre garden.

I got to the head of the line. I hesitated. Ursula crackled with impatience.

"I wrote a book," I blurted. "Will you give me a blurb?"

She studied me. "I only consider first novels by women."

"But that's me!" I beamed with reckless hope. "I have a contract from HarperCollins UK and Del Rey!"

She glanced over my shoulder at the line. "Fine. Send it through your editor," and signed the book.

So I persuaded my editor (brand new to the profession, like me — Ammonite was her first acquisition) to photocopy the manuscript on the sly and slip it into the company mail. And then I waited. Ursula sent back a lovely blurb — along with a lecture about the ridiculousness of unpronounceable Irish names. I wrote a thank you, and agreed about the names, which were intended as placeholders until, unhelpfully, the characters had grown into them. That this is who they were now, it was done.

In the last 25 years we've had dinner and lunch, drinks and conversations and a few disagreements. I've seen her cranky and delighted, tired and energetic, vulnerable and carved of adamant. I had always admired the writer, but I seriously like the woman.

I heard the news of Ursula's death on the anniversary of saying goodbye to my dying sister. I was already sad, but my response to Ursula's death shocked me with its strength. I wept helplessly. I wept until I couldn't breathe. And after a pause, I wept more. Ursula was not a close friend yet tears are running down my face as I write this. Why? Because I would not be who and where I am without her.

Ursula would not, in my opinion, have felt flattered to be the SF version of Virginia Woolf: the single woman who can not be erased from the school curriculum, the undergraduate survey course, or retrospective Masters anthology of SF or Modernism. To be seen as inherently different from other women, and for women to be strange unicorns in the wood of a male genre, would have meant that she had failed. She was not the first feminist SFF writer, nor the first to write about gendered worlds. She never claimed to be a trail-blazer or a path-breaker in this sense.

Ursula Le Guin's importance is as a deepener and clarifier of possibility. Her fiction combines cool prose with a burning sense of justice, and bends them in service of a powerful moral imagination to the examination of the human condition. In this examination, her fiction does not flinch. I can't speak to whether she was ever tempted to offer easy answers to difficult questions, but her fiction always refuses the easy choice. Rather, her stories excel at holding strong and opposing ideas in balance. Her fiction is ambiguous without being frustrating. That is her gift and talent.

In person, and in her nonfiction, Ursula was not ambiguous. She was clear, direct, and definite; she did not hesitate to let an interlocutor know when, in her not particularly humble opinion, their ideas were shallow, half-baked, or illogical. Unlike many other women she was not afraid to state her opinions. And unlike many other women, she was not punished for it.

Perhaps this was because her early fiction was dressed in a male persona and so did not hold the righteous rage of her era's other feminist SF; perhaps because she appeared safe — a white, straight-presenting, married upper middle-class mother — and she did not make the male gatekeepers of literary reputation defensive. But perhaps it was because she was so damn good at what she did. Her reputation now is as a colossus. She is a colossus made so partly by her talent, but also by her generosity. Since she gave me that first blurb, she has not only given me another but, more importantly, asked me for one. She didn't need a blurb from me or any other newer writer; it was her way of hauling us up onto the plinth beside her inside that walled garden. And now we are here and have a platform, we in turn are talking about Ursula, and her reputation grows. She deserves every bit of it.

Ursula did not lack a sense of self-esteem. She would have enjoyed many of the accolades being heaped upon her in these eulogies. But what might make her sad as she reads is that today three of those five writers I mention at the beginning do not yet have the reputation they deserve. For centuries the gatekeepers have been building that wall, designed with a single aperture to let through one woman writer at a time. I like to imagine Ursula would snort at this giant game of Highlander, in which There Can Be Only One, and call for us to tear that wall down. To paraphrase her speech at the National Book Awards in 2014: We live in patriarchy, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Resistance and change often begin in art, the art of words.

If you want to honor the memory of Ursula Le Guin, the next time you're asked what you're reading or whose work you love, talk about those the gatekeepers tend to turn away. And get writing.

Hibernation, Warming

Wind kicks a few cups down the alley.

Pocketful of stones, a greasy lot.

Morning chill in fleeting sunlight.You’d rather stay under this blanket agreement.

Not any storm can house you off the cuff.

The troposphere brushes your cold turned cheek.Wake up. Get the child to school.

Now you are alone in this story

of cornflakes and Tuesday frost.If you smell gas leak, all the more reason.

If you can walk back your talking point

happier still. Confusion in the hypodermis.Poverty of whiteness

or hostile witness —

you’ll need a hole to crawl intosoon enough. Who lingers

finds the daylight wary. Who wavers

stands for nothing still. Hypernation state of being always out of

reach for the sky. Though you thought

your silence golden.Though you felt like running

until your feet grew wings. This very morning

a crooked heartbeat stalked you out the door.

A winter cento, courtesy of sponsor Poetry Northwest

Sponsors like Poetry Northwest make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, reserve your dates now. We've got dates left in June and July (but feel free to contact us behind the scenes if you're interested in later in the year).

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from January 29th - February 4th

Monday, January 29: It’s Even Worse Than You Think Reading

The title of David Cay Johnston’s latest book, It's Even Worse Than You Think: What the Trump Administration Is Doing to America, about says it all. Johnston has already written one very good book about Trump, so this book is likely follow in that pattern: not many writers out there have genuine insight into Trump’s actions and management style, but Johnston does.- The Summit, 420 E. Pike St., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org, 7:30 pm, $5, 21+.*

Tuesday, January 30: Bothell Reading

Bothell is a lovely town, with a gorgeous river park and a very nice McMenamin’s movie theater and a charming small bookstore owned by an enthusiastic lifelong bookseller. This reading celebrates the launch of a book about the origins of Bothell, from a logging hub to a farming community to a thriving little burg of some 43 thousand souls. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, January 31: Passing the Torch

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Thursday, February 1: Storytelling Strategies for Dismantling Racism

Local writers help storytellers understand how racism affects their work and how they can help use storytelling to overcome those insidious systemic forces of racism in the world around us. Previous editions of this class received high marks and raves from participants. Centilia Cutural Center, 1660 S Roberta Maestas Festival St, 9:30 am, https://ssdrwinter.paperform.co/ $175.

Friday, February 2: Nasty Women Poets Reading

Seattle area poets including Kelli Russell Agodon, Jennifer Bullis, Susan J. Erickson, Susan Rich, Martha Silano, Judith Skillman and Carolyne Wright read their contributions to the new anthology Nasty Women Poets: An Unapologetic Anthology of Subversive Verse. Poetry won’t save us from Donald Trump, but poetry can help us understand the price of what we’ve lost and give us the strength to fight and win it back. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Saturday, February 3: Cascade Writer’s Event

Seattle-area writers Annie Bellet, Dongwon Song and Cat Rambo host a daylong event to help writers figure out how to compose, edit, and publish a long manuscript. This is one for aspiring authors who want to understand every aspect of the publication process, from pitching to editing to marketing. Queen Anne Baptist Church, 2011 1st Ave N, http://cascadewriters.com/, 10 am, $135.Sunday, February 4: Outsider Fashion Week

Fremont’s new-ish comics shop Outsider Comics and Geek Boutique is celebrating new shipments of spring fashion with personal shopper experiences all week. If you’re interested in trying on some of their new geeky outfits with direct one-on-one attention, you should make an appointment for any time this week. Outsider Comics and Geek Boutique, 223 N. 36th St, 535-8886, http://outsidercomics.com/, 10 am, free.Literary Event of the Week: Passing the Torch at the Seattle Public Library

Here we are at the end of January and 2018 is already shaping up to be a long year. Everything under the sun is either a disaster or a distraction from a disaster. We’re learning the horrible truth behind the legends that the media has printed for decades, and we’re realizing that nobody has any goddamn clue what’s going on.

It’s important, in the middle of all this chaos and drudgery and nightmare news notifications, to celebrate. Find a thing that you love, something that you’re proud of, and shout about it to anyone who’ll listen. Gather with friends and make a big scene. Enjoy what you have and make it matter.

This Wednesday, the last day of January, at 7 pm in the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library, outgoing Washington State Poet Laureate Tod Marshall will celebrate the end of his triumphant two-year tenure. Marshall has been a great force for poetry in this state, advocating tirelessly for Washington poets, even publishing an anthology of local poets titled WA 129.

Tonight, Marshall passes the torch — it’s a metaphorical torch, don’t get too excited — to the state’s incoming Poet Laureate, Claudia Castro Luna. Luna was until recently Seattle’s Civic Poet, which is basically a poet laureate role for the city. Castro Luna and Marshall will be joined by Seattle’s current Civic Poet, Anastacia-Renee, making this evening a veritable who’s who of government-sponsored poetry. (Somewhere, Paul Ryan is undoubtedly clawing at his own eyes and shrieking into the night at the thought of government cash going to poets at all. Fuck that guy.)

Other Washington poets will be onhand, too, to read their own work and to celebrate Marshall’s tenure and to welcome Castro Luna to the new job. Readers include Duane Niatum, Georgia McDade, Phillip Red Eagle, Quenton Baker, Rachel Kessler, Dawn Pichon Barron, Bill Carty, and Shankar Narayan. Look: it’s dark and wet and cold outside. Why not go where it’s warm and people are smart and appreciative and kind? You know, for a change?

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.

The King County Council wants more control over 4Culture. Tell them why that's a bad idea.

King County Council introduced an ordinance — Ordinance #2018-0086 — to give the Council more control over 4Culture, the county's cultural funding agency. The ordinance would allow the Council to fire the executive director of the organization, and to name a majority of 4Culture's board of directors. (You can read more about it on 4Culture's own site.)

This all seems rather silly to me. It's not as though 4Culture has done anything wrong — the organization oversees a ton of grants and artist residencies and artist visibility programs, with virtually no controversy and/or scandal along the way.

Look, I'm for big government: health care, regulations, taxes, you name it. But I don't understand why King County Council needs tighter reins over 4Culture. The one part of city life that I don't want the city to have more control over is arts and culture. Why not let the experts handle it? Why give elected officials more control over which artists get what funds and why?

If you agree with me, maybe reach out to the King County Council and ask why, in a county with one of the worst homelessness crises in the nation, this has become a priority. Tell them why you like 4Culture the way it is, and let them know that we don't want more direct Council oversight of our cultural resources.

The Sunday Post for January 28, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

How I stopped being ashamed of my EBT card

In this personal essay about the social stigma (and social anxiety) associated with using food stamps, Janelle Harris deftly de-others people who rely on public assistance to feed themselves and their families.

I built a career as a staff writer and editor that didn’t require me to work the same tiring hours in the same factory conditions that my mama did, and still does. I had all the tools I needed to live a life that — if it couldn’t be sleek and sexy like a Maserati — could at least be functional and dependable like a Jeep.

In 2012, when I was fired in an abrupt mass layoff from a job that was supposed to be reliable and steady, I decided to make a full-time pursuit of the freelance writing I’d been doing on the side for years. I knew I was taking a risk, and I was prepared for lean times. As a young single mom, I’d struggled financially through all of my adult years anyway. But I never considered that the trade-off for chasing a slow-materializing dream would be abject poverty.

The female price of male pleasure

In response to the backlash against “Grace,” the young woman who spent a more-than-uncomfortable evening with Aziz Ansari, and to Andrew Sullivan’s “testosterone defense,” Lili Loofbourow talks bluntly about bad sex. Can we not distinguish between sexual assault and sexual bullying and still reject both?

One side effect of teaching one gender to outsource its pleasure to a third party (and endure a lot of discomfort in the process) is that they're going to be poor analysts of their own discomfort, which they have been persistently taught to ignore.

In a world where women are co-equal partners in sexual pleasure, of course it makes sense to expect that a woman would leave the moment something was done to her that she didn't like.

That is not the world we live in.

When ‘Gentrification’ Isn’t About Housing

Gentrification happens in waves of displacement; even the “virtuous” wave of artists and writers who make a neighborhood cool are pushing something else aside. Willy Staley has cautionary words for the affluent gentrifiers who push aside the artists — and who think their castles are built on rock.

New York’s skyline is erupting with buildings like these — stacks of cash-stuffed mattresses teetering in the wind. And The Times reported last year that the West Village’s Bleecker Street had fallen victim to “high-rent blight,” with commercial space becoming so expensive ($45,000 a month) that even Marc Jacobs couldn’t keep his stores open; shops that once catered to the wealthy now sit empty, waiting for a tenant who can foot the bill. When the heist is done and it’s time to split the loot, capital snuffs out culture.

Searching for an Alzheimer’s cure while my father slips away

Documenting his father’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease, Peter Savodnik writes about how the disease devastated his own memories.

Madness is the nub of it. In the beginning, everyone — the patient and the people who love the patient — goes a little crazy. It’s only later, after you begin to see things better — not through the prism of denial or hope, but through statistics — that you realise none of those pills are likely to accomplish anything; that garden therapy and watercolour therapy cannot, in fact, heal damaged tissue; that the numbers cannot be spun. You are in a darkened room without doors or windows.

Whatcha Reading, Kevin Craft?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Kevin Craft is the director of the Written Arts Program at Everett Community College, a poet, and longtime editor at Poetry Northwest. He's also our Poet in Residence for January.

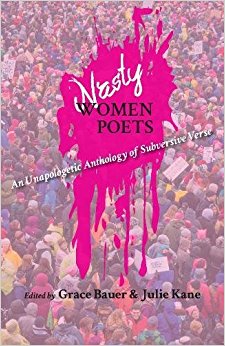

What are you reading now?

I'm just finishing Langdon Cook's Upstream: Searching for Wild Salmon from River to Table. It's an adventurous book — a wilderness of reportage, zigzagging all over the Pacific northwest, from Sacramento, CA to Cordova, AK, from the mouth of the Columbia to the source of the Snake, investigating in detail the history and current status of wild salmon populations. We get the big picture from this book: Native practices, the plundering greed and hydro-technical faith of Euro-settlers that caused salmon populations to plummet, the mixed blessing of the hatchery programs, the wild runs that remain. Cook connects it all to the way we live now: how salmon finds its way to supermarkets and restaurants and backyard grills. His prose is colorful, punchy, brisk — driven by a profound if understated sense for the tragedy of environmental degradation, though his real skill is hooking in the many fascinating, territorial characters who make a living around salmon, bringing their hopes and struggles for a sustainable future to the page.

What did you read last?

I recently finished reading Paisley Rekdal's Imaginary Vessels (Copper Canyon Press, 2016), alongside Jason Whitmarsh's The Histories (Carnegie Mellon Press, 2017) with a group of poetry students. I was interested in exploring what is sometimes called "documentary poetics" from two very distinct angles. Rekdal's book is a brilliant example of this kind of writing: it is many documentary angles in and of itself, including a suite of recombinant sonnets written in the voice of Mae West, and sequence of sonnets paired with photographs of anonymous skulls found buried in a Colorado state mental institution. The abiding pathos with which Rekdal restores these lost voices, the comical and the tragic, deepens our sense of what poetry, as vessel and vicissitude, can accomplish in a time when public memory is all slippery slope and sloppy lies. By comparison, Whitmarsh's table of contents (most begin with the title "History of...," such as "History of Therapy" and "History of Language") reads like the course curriculum of an eccentric liberal arts degree. Most are prose poems, short fables of modern life infused with wry, quiet humor. The prevailing voice is detachment — the dead-pan mode of Lydia Davis comes to mind — detailed like a scientific proof of some elusive emotional experience. As "documentary," these poems remind us that the facts of history may be hard to nail down, but we live inside our own fictions anyway, and we're better off learning how to navigate the absurd than pretending the world can ever be made right or whole or perfectly understood.

What are you reading next?

I have a number of books lined up for a new course I'm teaching in Young Adult Literature, starting with Kirstin Levine's The Lions of Little Rock. It's such a great, eye-opener of a story, depicted in smart detail from the perspective of a shy middle school girl struggling to find her voice. I plan to revisit The Outsiders, and move from there through some recent classics and hopeful bestsellers in the genre — Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak, Erica Sanchez's I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, Reynolds & Kiley's All American Boys, and others like it. Finding voice is a natural theme of adolescence, of course. So is parsing right from wrong, learning how to recognize truth, forming moral character and judgment. I'm interested in seeing how these themes play out in stories addressing social justice, group adhesion or exclusion, racial segregation, gender conformity, the works. I've got my hands full, no doubt. We'll see how it goes — I'm excited to discover what my students are thinking and seeing now.

January's Post-it note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we’re posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson’s Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here’s her wrap-up and statement from January's posts.

January's theme: Ordinary Impossibilities

Last month I was at a party full of strangers, trying to find ways to talk. There were several queer women; naturally I wanted to make friends. (Multiple queer women in the same place, so exciting! We are so few! How magical to happen upon a gathering that is more than three percent us! I was playing it cool.) We worked effortfully through typical small talk, before brilliantly hitting on television—a conversational jackpot, because TV and film have treated LGBTQ people so badly. The higher the production caliber, the more torturous the story—pretty much the best we can hope for is devastatingly failed romance. Comparing notes on which shows kill off lesbian characters is a real must for my psychological well-being. Someone reminded me of the movie Carol, which pulled a surprise happy ending out of the usual bleakness. I’d say spoiler alert, but it doesn’t spoil anything—I wish gay stories all came with one so I’d know what’s worth putting myself through. It turns out in January 2016 I’d made a post-it about watching Carol. David Bowie died that same month; I have to accept that I will never know or be known by this person whose work meant so much to me, and there is no perfect likeness to be made of him. But I can make that feeling into something anyway. These are instances when something ordinarily impossible works out. I hold on so tightly to memories, but every now and then I can let go, find I’ve forgotten something about someone who hurt me. Or, randomly discovering a single surviving Victorian farmhouse perched between huge new buildings, like a secret from the past waiting for me to walk a new route to work. These moments never solve the giant wrongness of our world right now, but they do solve something inside me.

The Help Desk: What book would you give to your teenage self?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

If you could give one book to yourself as a teenager, what book would it be? It can be any book from any time, even if it was published after your teen years.

Helga, Crown Hill

Dear Helga,

What a wonderful question, as one of my favorite pastimes is stewing in regret. Your question reminded me of a time in my early 20s when I told a good friend and mentor (who is male) that I didn't think women wrote as well as men. My comment was the product of what I'd been exposed to in school: illustrious male writers I admired and identified with, and the occasional woman thrown in whom I did not: Barbara Kingsolver, Jane Austen and Anne Frank. The female authors I read on my own were mostly romance writers and other genre authors, and while I enjoyed their work I didn't want to emulate them.

When that thoughtless comment fell out of my mouth, my mentor did not correct or lecture me. He simply gave me a look of pity and then did the same slow fade I employ at parties when someone four beers in says, "Well if I was a girl I'd take it as a compliment." That pitying look prompted me to search out and read contemporary female authors and, unsurprisingly, I found a ton of work that I identified with and authors that I now love.

If I could go back and give my teenage self one book, it would be Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping, which is one of the most beautifully constructed books I've ever read. (Also, Robinson is from Idaho like myself, and should be celebrated more in her native state instead of a lionized dude like Hemingway, who simply shot himself here.)

I would also give myself Claire Vaye Watkins's essay "On Pandering," which every female writer should read.

Kisses,

Cienna

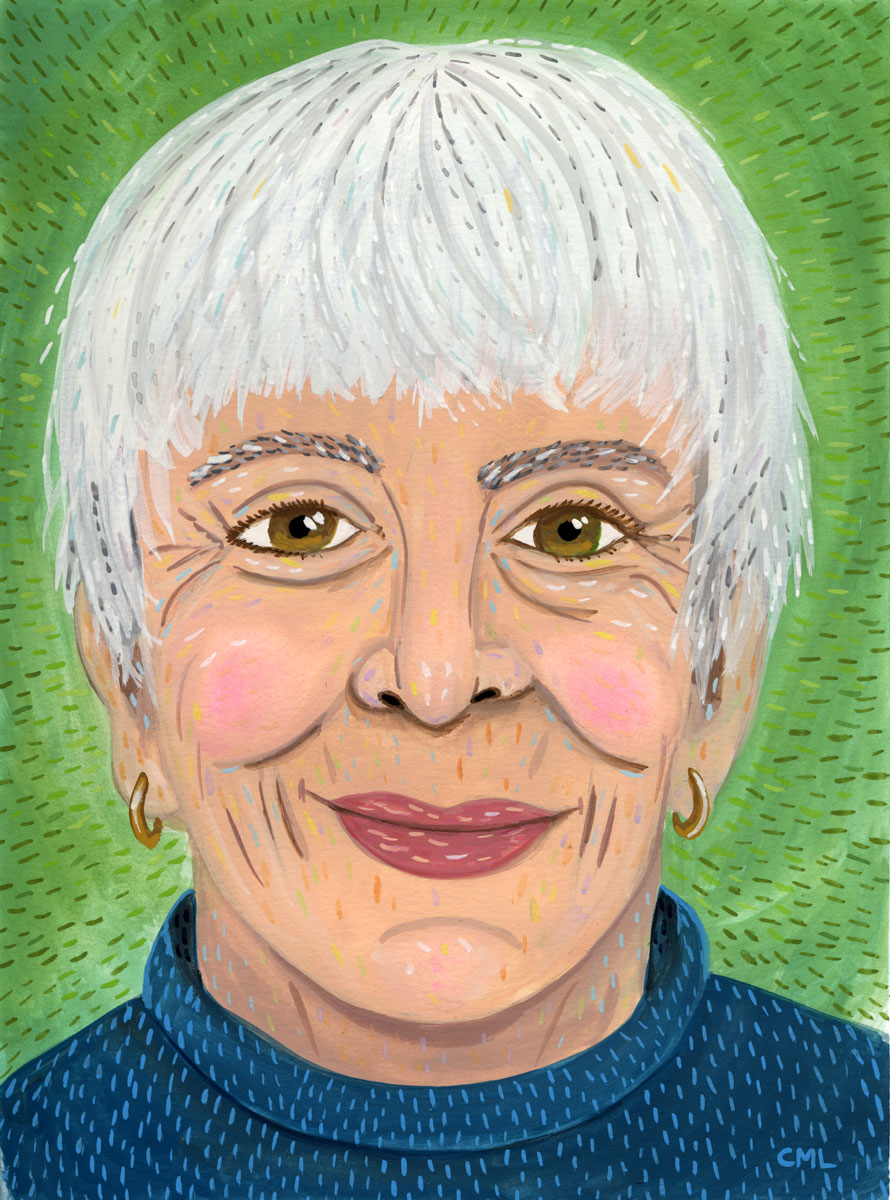

Portrait Gallery: Farewell Ursula K. Le Guin

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Farewell to Ursula K. Le Guin

Fierce, visionary, legendary, human.

Criminal Fiction: The best of the quintessential interviews

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page

Daneet Steffens is taking a well-earned month off. But don’t worry — you can still get your Criminal Fiction fix. Browse the archives for more than a year’s worth of recommendations; Daneet casts a wide net, and every column is a gem: a handful of smart short reviews and an interview with a writer of note, topped by a recap of genre news, a list of essential articles, or a podcast worth your time (follow her on Twitter for a constant feed of the same great stuff).

Here are just a few of our favorite “quintessential interviews”:

- Ruth Ware: "I love a pub with a proper beer garden."

- Elizabeth George: "I write in silence unless my dog starts barking."

- Dennis Lehane: "There are at least 700 songs on my Infinite Writing Playlist."

- Chris Holm: "I’m fascinated by what drives good people to do bad things. By how bad one can be without becoming irredeemable. By the slipperiness of identity and what we consider to be our essential selves."

- Justine Larbalestier: "Never have more than one psychopath: it strains credibility."

- Lori Rader-Day: "What people whisper about is what they care about."

See you next month!

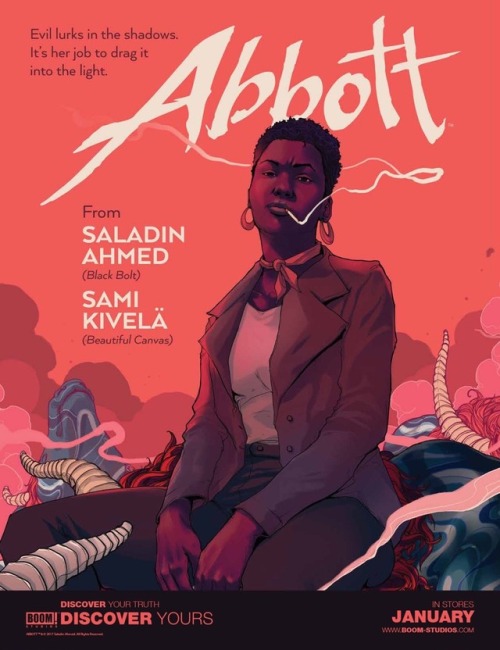

Thursday Comics Hangover: Less talk, more rock

I enjoyed the first issue of sci-fi writer Saladin Ahmed's Black Bolt series for Marvel Comics, but I ultimately didn't continue with the book, because Black Bolt is the very definition of a one-note character. The best writing in the world couldn't make an aloof mute king with a tuning fork on his forehead a compelling protagonist. But there was so much talent in evidence in that first issue of Black Bolt that when I saw Ahmed had a new creator-owned series coming out from Boom! Studios, I was eager to give it a try.

Abbott, published for the first time yesterday, is a new series about an African-American newspaper reporter in 1972 Detroit. Elena Abbott is described in the first issue of Abbott as a "black Lois Lane," but Ahmed admits in interviews that he envisions the character as more along the lines of the cult TV show Kolchak the Night Stalker.

A tough Black journalist on the mean streets of 70s Detroit, fighting supernatural menaces? Yes, please! Abbott has all the makings of a great comic series, and artist Sami Kivelä is a revelation: he draws apartments that look lived in, and figures that have lived entire lives. It's a flat-out gorgeous book.

It's a shame, then, that the first issue of Abbott suffers from a pretty severe cass of first-issue-itis. There are a lot of word balloons here covering up Kivelä's beautiful artwork, and a lot of them could have been trimmed. The exposition flows hot and heavy, with a lot of telling and not enough showing. Early in the issue, Abbott shows up at a crime scene with her own camera. She's greeted by an older white photographer. This is their exchange:

—Holy crap, Abbott, Fred's got you taking your own pictures now? That's ridiculous. He giving you any kind of budget?

—Hello, Murray. It's not Fred. It's the higher-ups. Someone didn't care for my police brutality stories. I'm being punished.

—That's too bad. You're a good reporter, Abbott. A damn good reporter. Better than the little @#$%& I'm working with now.

—Thank you, Murray. And you're the best crime photographer in Detroit.

—Now you're just flattering me.

—Well, it is possible I'm hoping you'll tell me what the police know here, since no one else will.

This exchange desperately needs an editor. There's way too much backstory and repetition and cross-talk for the first few pages of a comic. I'd love to see Murray and Abbott's history relayed through an intimate exchange that didn't lay everything out so plainly.

As the issue carries on, Abbott starts to pick up in pace, building to a cliffhanger that really sets the premise in motion. I'm definitely coming back for the second issue. But I'm also willing to bet that the second issue of Abbott should have been the first issue; dropping the reader in the middle of the action and forcing them to figure out the story as it goes along is always preferable to explaining everything.