Seattle Writing Prompts: Seattle Central Library

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

We've written about the library before. In fact, not long ago, I wrote a story about the library and its design, while talking about Safeco Plaza, but, much to my surprise (because, you can forget what you've written about, sometimes), I've never featured the library for this column.

It's the third library to occupy this spot, squared in between Madison and Spring, and 4th and 5th. There once was a grand old Carnagie Library on the spot, built in 1906. It was demolished in 1957, and a new library, in the International Style, was opened in 1960.

The Rem Koolhaus design of the new library was shown in 1999, with our current incarnation opening in 2004. Does the building feel thirteen years old to you? I can remember visiting it, the first time, and it seemed new and fresh. Now, children born the same day it opened its doors are going through puberty, and have never known our city without it.

Sometimes, I visit the library and climb all the way (I never take the elevator) to the topmost floor, to the Betty Jane Narver Reading Room, otherwise known as the finest secular cathedral in the world. When I'm finished, I walk down the spiral. It's so satisfying to step on those rubber mats, the Dewey Decimal classification numbers inlaid in in white Futura bold on a black background.

Then, just slip into a stack at a random place, and look around. You're in the books, and who knows what you might find? It may just be something amazing, something with a story, something you could do to pull off the shelf and lose a little time with Maybe you'll find some stories there?

Today's prompts

- Philosophy & theory; international languages: We are unknown to ourselves. These men break up with each other in the library stacks. Arguing quietly, one who was always embarrassed by the simpleness of the other, the second who was always embarrassed by the way the first put on airs. One grabs Thus Spoke Zarathustra and shoves it at the other. "Here, work on becoming an Ubermensch". The second grabs The Gay Science and says "Here, study at this, and go fuck yourself."

- Geometry: "Thales of Miletus," she said to her brother. "Who?" — "Thales of Miletus! You don't know about him?" — "Should I?" — "Uh, yeah, dummy. He calculated the heights of the pyramids." — "Uh, so what?" — "He was rich because he predicted the weather and went hard on olives one year." — "Why did you bring me here?" — "We're gonna get a book about geometry!" — "I hate you" — "you won't when I get you into college. You're gonna love Thales of Miletus. He's the bomb."

- Mammalia (Mammals): He walked down four aisles, eyes half closed, counting down from one hundred, dragging his finger across the books. While he walked, he counted steps in rounds of four, so that the two patterns of numbers moved in different cycles, one of tens and one of fours. When he reached zero, his finger was resting on a book on the third shelf, but he ended his step on a two, so he went directly down one, and pulled out a book on whales. He looked at the time (3:19pm), and then went for three groups of nineteen pages, and rested his finger on a sentence that told him that the average blue whale penis was seven to ten feet long.

- Food & drink: She couldn't find the recipe. Maybe it was because of the boys running crazy. They wouldn't stay downstairs in the children's area, not without her, so she had to bring them up in the stacks. Now they were running circles around the row of shelves, where she stood, looking through the cookbook her grandmother used to keep on her shelf, trying to find that one thing she wanted to make for the holidays, all the while, the boys screamed and ran.

- American poetry in English: It was a quest to write a villanelle. It started with a promise to look nothing up on the Internet for the entire month of December. Then, a friend challenged her to a poetry writing contest, and she had one week to deliver a form she had never heard of. Only one way to find out...

The Help Desk: A very Help Desk Christmas

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Do you have a favorite Christmas book?

Timothy, Licton Springs

Dear Timothy,

Yes, I do: David Sedaris's Holidays on Ice. But if you haven't read it, don't bother – listen to Sedaris read Santaland Diaries instead. Back before the internet consumed 90 percent of our collective attention, this was a highly anticipated Christmas tradition in my household. Sedaris is a powerful reader of his own work and my family had to tune in to NPR at just the right time to catch his dry retelling of what it's like to be a Macy's Christmas elf named Crumpet. His story will make you love elves, hate children and pity those who give birth to them.

Kisses,

Cienna

Dear Cienna,

With all the GoFundMes and the Giving Tuesdays, I don’t know what to do with my charitable giving anymore. Do you have any ideas for which literary nonprofits are especially worth my time?

Don, Roosevelt

Dear Don,

I'm thinking of starting a nonprofit that would pay women to run around and give men titty twisters while screaming "REPARATIONS!" But until that gets off the ground, Hugo House is one of my personal favorites; The Greater Seattle Bureau of Fearless Ideas (formerly 826Seattle) is fantastic; and Seattle7Writers is stacked with great people doing great work.

Kisses,

Cienna

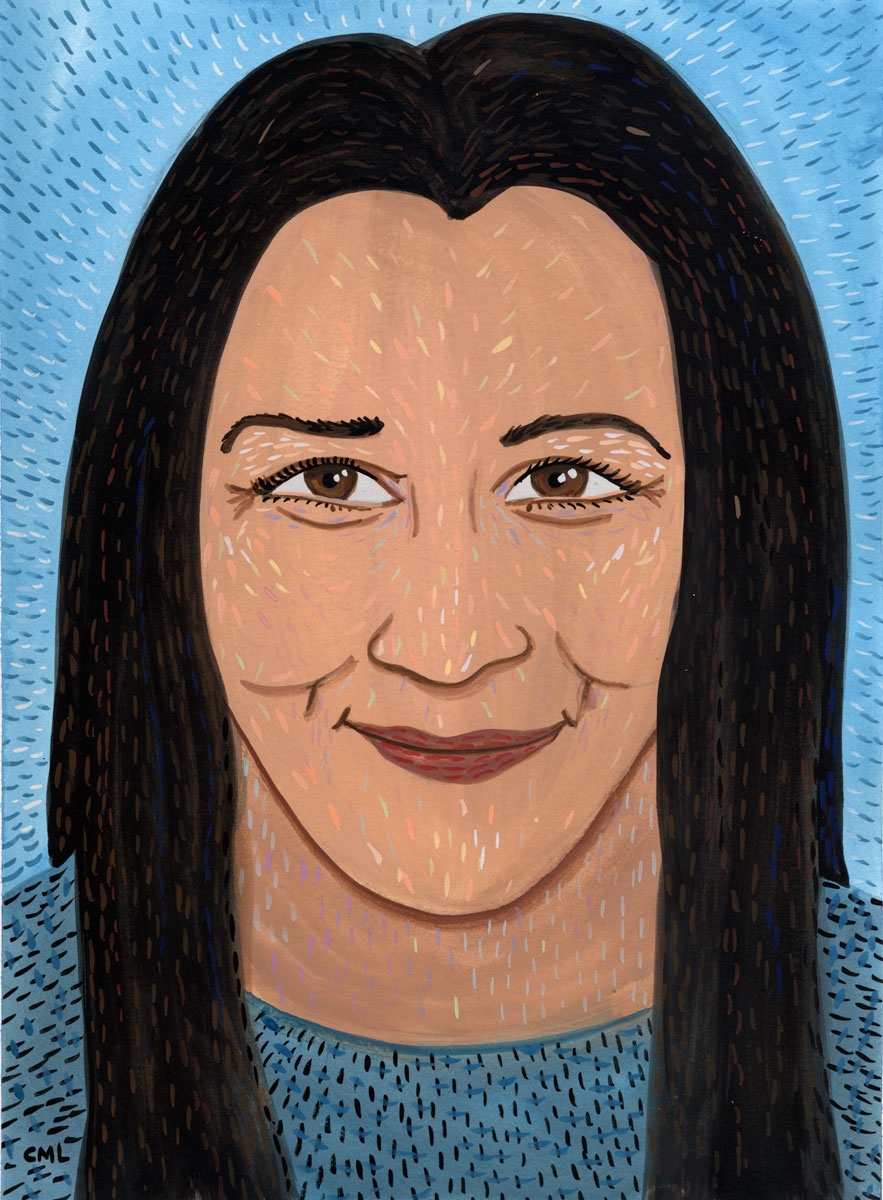

Natalie Diaz

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, December 7: Poetry Across the Nations: An Indigenous Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030. http://www.hugohouse.org, 7:30 pm, free.Kissing Books: historically speaking

New Column! Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it?

So now comes the end of this year of years, where the days have piled up like stones, each new one adding a fresh ounce of dread to the heap. I’m always thinking about time in the winter — thanks to my favorite piece of time-travel fiction, A Christmas Carol — but 2017 has played an extra merry hell with my sense of the daily ebb and flow. So I’m peering at time with double-surly eyebrows this December.

Historical romance is the most obvious place to start talking about how romance novels engage with the concept of time, because being set in the past is their defining feature. You recognize a historical romance because shows you Then rather than Now. And it’s usually at least a hundred years in the past — despite treasured examples like the Fly Me to the Moon series and ’s excellent Tang Dynasty books and this disco romance, by far the bulk of historical romance falls in the long 19th century. There are more than a few overlapping theories about why this happened, keeps happening, and will presumably keep happening for some time to come.

For one, the obvious influence of 19th-century genre originators: Jane Austen and Jane Eyre are both still wildly popular and much imitated. People tend to overlook the fact that Jane Austen was depicting her contemporaries but Brontë set Jane Eyre thirty years in the past. Georgette Heyer came along in the early decades of the twentieth century to finish establishing the Regency romance, and by the twenty-first century the genre’s borders had been widened to encompass the Victorian era. (Possibly because of long family-based series with multiple generations? Bertrice Small and Stephanie Laurens come immediately to mind.) Romance authors often start writing to be part of a conversation — they respond to a book that moved them, or correct a book they think could or should have gone differently. So the setting, once established, gets reinforced by later writers. At some interesting point whole sections of this woven net of texts began to drift away from historical reality and became a shared imaginary world (probably around the time Heyer started inventing her own Regency slang to catch plagiarists).

The existence of this shared world means an author can choose to blithely set aside the realities of 19th-century populations (many fewer dukes, many more black and brown and queer people) and handwave matters of plumbing and dentistry and STI rates. The Regency becomes a sort of fairy tale in historical dress — what readers refer to somewhat scornfully as “wallpaper historicals” (see Eloisa James’ A Kiss at Midnight for a particularly obvious example). Let’s be clear that choosing to leave chamberpots unmentioned in 1820s London is a much more forgiveable omission than leaving black or brown folks out of 1820s London. It’s not the fault of any individual book (or duke), exactly, but the overall pattern is distressing. More understandably, there is the attractive public pomp and performance of aristocratic marriage, which is currently flooding my timeline with engagement photos and delighted anticipation for a new princess bride. Whether you’re royal and titled or merely landed gentry, aristocratic marriage is about preserving property against the passage of time: the whole point is to pass the manor house and its wealth down to your heirs, unaltered.

American-set historicals, it seems to me, especially lately, engage with the past very differently. The chronological borders here are expanding, too — edging back into Hamilton territory and forward into the hedonism of the Roaring Twenties — but most are still set during the latter half of the 1800s. Particularly around the Civil War and the colonization of the American West (origins in Laura Ingalls Wilder, Margaret Mitchell, Kathleen Woodiwiss, and, according to this persuasive essay series, Indian captivity narratives). If the majority of British-set historicals keep historical events at a polite distance, American-set historicals use the past very deliberately as a mirror turned back toward the present. (Admittedly, this is at least partly due to my own reader bias as an American.) America in the 19th century was a work in progress in a way England was not and had not been for centuries. The characters aren’t merely heading West, they’re heading here, toward the future; they are creating the towns that will become the cities where the reader presently lives. Southern romances don’t just describe the battles of the Civil War: they are still fighting it — on the one side you have the plantation romances starring white slaveowners that began with Kathleen Woodiwiss and Margaret Mitchell but continue to be published and even unnecessarily, hurtfully reissued; on the other hand you have Alyssa Cole’s Loyal League and Beverly Jenkins’ black heroes and heroines of the Underground Railroad. Are there really readers who can enjoy both equally without some gold-metal mental gymnastics? I remain skeptical.

Which is not to say the American-set historical romance does not have its own particular problems of idealization and erasure. You’ll find plenty of mentions of Native and half-Native American characters in romance over the years, but barely a handful of those have been written by Native authors. And we are currently living through a time where the failures of bootstrapism and capitalism and the wholesale plunder of natural resources are staring us all right in the face — so mining towns and lumber camps and railroad expansion have lost their luster of progress.

And of course, because romance is a multi-headed hydra, all of these generalizations have exceptions. Below I gush about the newest Alyssa Cole, which reaches far back beyond its American setting and into Stoic philosophy; I also review an India-set book with a laboring-class hero that manages to critique the capitalism of the East India Company while avoiding exotifying racist clichés and exploitation of suffering.

See you again in the brand new year. May you give this old one the send-off it deserves.

Recent Romances:

Seared by Suleikha Snyder (self-published: contemporary m/f):

For a moment you couldn’t swing a dead duke around in the romance genre without hitting a stepbrother romance. Some followed in the illustrious footsteps of Clueless, others were more Say It Isn’t So. (Remember Chris Klein?) The mini-trend has passed, as they always do, but thankfully not before Suleikha Snyder got her hands on it. Hotter and more playful than her Bollywood romances, this book walks right up to the comfort line, stops long enough to wink at you, then sashays boldly forward into WTF territory. Whether that’s fantastic or far too much is going to depend entirely on the reader. Naya and Lachlan’s parents married when she was sixteen and he was twenty-one; the youngsters had an instant connection but (importantly for this reader’s comfort) did nothing physical about it. Now a decade has passed, Lachlan’s vicious, controlling father is dead and can’t stand in their way anymore: she’s an international soap opera writer, he’s a billionaire celebrity chef, and they’re both kinky as all get-out. They do it. A lot. Improbable amounts of sex. This book has heard of realism and wants nothing to do with it — every encounter is intense, mind-melting, over-the-top, and damn near perfect. Naya is a submissive but not at all a docile one, and Lock is definitely a dom who needs bossing around every now and again. The arguments are heated. The chemistry is palpable. And the food puns are exquisite.

But his eyes were unchanged, and his mouth still fought smiles like a knockout was imminent.

A Hope Divided by Alyssa Cole (Kensington: historical m/f)

Some romances let you escape. This romance will set you free.

Ewan McCall is a Union army interrogator, currently held in a Confederate prison. Marlie Lynch is a free black woman, the unacknowledged daughter of a wealthy white slave owner, who with her white sister brings food to the prisoners (and smuggles information in and out, of course). What begins with small notes scrawled in the margins of ancient philosophy texts flowers into one of the most gorgeous epistolary romances I’ve ever read: Ewan is injured escaping from prison, and Marlie hides him in the Lynch’s attic where she makes healing tonics and salves. They are only feet apart, but the necessity of silence forces them to write to one another rather than converse. This part could have gone on for another thousand pages and I would have treasured every word.

Ewan has leaned on Stoicism to get him through an abusive childhood, but his philosophy of resisting desire is slowly, irresistibly undermined by Marlie’s brilliance and beauty. For her part, Marlie has been betrayed in large and small ways by everyone she ever trusted, and guards her heart with a fierce and furious pride. There is a whole living world inside this book; it feels less like something I read and more like something I inhabited, or devoured, or dreamed. I paused briefly in chapter two to read through Epictetus’ Enchiridion so I could fully appreciate the way the book engaged with his particular strain of Stoic thought — and this was completely the right call, because this romance looks around, rolls up its sleeves, and begins taking the whole world apart. What it means to be a good person, what it means to love someone, what you can and cannot control, how to deal with a personal and political history built on pain and loss — Ewan and Marlie set all these questions to boil, distilling them down to their essences in search of a life pointed toward truth and goodness. And love, though the word only hovers lightly over the text, letting the sheer devotion and bravery of the characters do all the heavy lifting. It is an astonishing, glorious read from which I may never recover.

She should be quiet and unassuming, given the secret she held two flights of stairs away, but apparently her rebellious side had begun to bloom, like a nightshade that unfurls when shrouded in darkness.

A Midnight Feast by Emma Barry and Genevieve Turner (self-published: historical m/f)

If you’ve read the other books in the Fly Me to the Moon series — midcentury space race historicals set in a fictionalized NASA, and they’re great — you’ll know Margie Dunsford runs everything socially for the astronaut wives. You’ll also know she and her husband Mitch have only the tattered shadows of passion left for one another. This longish novella, just shy of a full novel, stretches backward and forward in time to show us the Dunsford marriage as it rises, falls, and ultimately rises again. Marriage-in-trouble romances are hard to get right because they have to be more inwardly focused than other romance types: wondering if a partner is The One requires much less introspection than trying to decode What Went Wrong, how much blame falls to either side, and whether anything real can be salvaged. This book is a deep dive into the way two people can grow apart without realizing it, and watching Margie and Mitch as they make and unmake a lifetime’s worth of mistakes is both acutely painful and wonderfully rewarding. All this against a 1960s background of Jell-O molds, cocktails, and crinolines. It’s not the heart-smashing masterpiece that Earth Bound was, but it’s a damn fine book.

It had been like playing a part — but he knew all about that. These days he glided through life. He said the lines and did the work until he couldn’t separate the pretense from reality. Maybe that was the secret: there wasn’t any other, better reality. This was it.

Discovery of Desire by Susanne Lord (Sourcebooks: m/f historical)

The steps for reading this book are as follows. One: Oooh, what a pretty cover! Two: Is that a blurb from Courtney Milan? Three: turn to first page. Four: fall headlong in love with the giant, lumbering diamond-in-the-rough hero and the petite, managing, steely heroine. Seth Mayhew spent years hunting orchids in the jungles of Brazil: now he has come to Bombay to search for his missing sister. His translator meets him at the wharf — but Seth is not the only person he’s waiting for. Turns out the translator has gotten himself engaged to a venture girl (mail-order bride) from England, a poised and pretty problem-solver named Wilhelmina Adams. Minnie, as Seth almost immediately begins calling her, has made the journey with her sister, another venture girl whose fiancé just so happens to be a botanist on the same crew as Seth’s missing sister. There are so few coincidences in romance.

The sense of place here is phenomenal, a tropical port city so vividly rendered that you can all but feel the humid sweat on the back of your neck. The characters, too, are vivid and engaging — Seth’s easy if unpolished charm (as a younger man his sister named him the Worst Flirt in the Midlands) makes for a lovely contrast to Minnie’s formality and directness. The last third of the story returns to London for a bit more angst than was probably required, but this small flaw is more than made up for by the fact that we get a suspenseful orchid auction scene at the climax where all our hero’s hopes for love and happiness rest on one question: how much will these unbelievably rich obsessives pay for their pretty, useless plants?

All these charms aside, this book is an excellent example of how to confront the evils of racism and colonialism while still staying firmly in your lane as a white author. We don’t need a fetishizing setpiece of Brown People Suffering to show how cruel the men of the East India Company are — instead we see how much indifference they wield against our white-but-laboring-class hero and are explicitly invited to extrapolate outward to India and the whole British empire. The Company men’s sense of entitlement is palpable and terrifying, and Seth’s role as an explorer/gatherer for the company lets him reveal how deeply greedy they are as a group: “They take away everything. Anything they can take, they’ll take.” It’s a narrow view onto a vast, complex issue, but it deftly avoids many of the exotifying pitfalls we’ve grimly come to expect from so many India-set historicals. Later scenes of working poverty in London’s lower-class neighborhoods bring this book surprisingly close to a critique of capitalism.

There wasn’t a wrinkle on her skirts or a wayward crease in its folds. And that straight spine was all the sight he had of her — she didn’t fidget and she didn’t turn. Composed, capable, orderly-like. He’d drive a woman like that to Bedlam. But he fell a little bit in love with her anyway.

This Month’s Scrooge of a Heroine

A Christmas Bride by Mary Balogh (Dell: m/f historical):

Like many writers, I often imagine plot as a physical shape: an arc that rises and falls, a set of points in a constellation, a circle coming back around to its starting point. We talk of enemies-to-lovers or marriage of convenience tropes as though they are ready-made vessels waiting to be filled. As though what we pour in there — which is to say, the fluid stuff of character — does not affect the nature of that shape.

If you fill a champagne flute with hemlock, can you still call it a champagne flute?

Plot-wise, A Christmas Bride has the sweet shape of a classic Christmas Regency: Mr. Edgar Downes is a wealthy self-made man whose father is insisting he take a genteel bride before Christmas. He has his pick of docile, well-behaved prospects, but becomes entangled with a woman who is both irresistible and totally unsuitable as a marriage prospect. An unplanned pregnancy compels them to wed, emotions develop and are revealed, a happy ending arrives just when it seems least likely. It’s a shape designed to sparkle, whether you fill it with cheap cider or the most subtle and exquisite blanc de noirs. I’m an experienced reader: I came looking for sparkles. I anticipated a saucy bluestocking or blushing wallflower would prick Edgar’s ego and disturb his comfort. Hell, so do the secondary characters, fresh from their own recent and fertile romances: “The combination of a wedding an an imminent Christmas was enough, it seemed, to transport everyone to great heights of delirious joy.”

Expectation is shattered when we meet the Lady Helena Stapleton, a well-traveled widow of thirty-six. She shows up late to the ball in a red satin gown and a mocking smile, bangs our hero like a drum, and sends him home with nary a cuddle. Her attitude toward her surprise pregnancy is less secret baby and more get this facehugger off of me. She is bitter, brilliant, cynical, sharp-tongued, and, of course, emotionally scarred. Many of the reviews you’ll find mention disliking the heroine — and some of the things she’s done really are terrible. Helena is not a nice person; in fact, she’s the villain in an earlier Balogh book. She is clear-eyed enough to see the shape of the holiday romance crystallizing around her, but stubborn as she is she has to be dragged toward her happy ending under constant cursing protest. She does not want to be dragooned into happiness. She would rather be left alone.

Her presence changes the nature of her story, even though all the plot points came along in the usual order. I’d expected Edgar to be the one transformed by love and seasonal sentiment; instead, we end up with the grand battle of Hemlock Helena Versus the Redemptive Coziness of Christmas: “The great myth lifted ones spirits only to dash them afterward even lower than they had been before. She had feared it this year and sworn to resist it.” She has not been poured into the story like an afterthought — the proper metaphor here is not the champagne in the glass. The image we are looking for is chemistry: we have mixed two elements, and the mixture was beautifully volatile.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The hardest button to button

So as you probably know by now, writer Geoff Johns and artist Gary Frank are publishing a sequel to Watchmen titled Doomsday Clock. I don't really know what to say about the first issue of the book, except it is drenched in nostalgia. It's the kind of book that ten thousand teenage geeks dreamed they'd get to write after they read Watchmen for the first time. Doomsday Clock reads like a cover version of Watchmen, a mimicking of Alan Moore's tone without the intellect to back it up.

At least the art is pretty. Frank is one of the best contemporary superhero artists, though it must be said that his work is changing in an unpleasant way with each passing year. The faces of his characters are getting tighter and more pinched; the poses seem more coiled with every new page. The looseness and excitement of his early work seems to be replaced with a dour and puckered over-rendering, and it's kind of sad to watch. I want to start a GoFundMe to send him on a nice relaxing vacation or something.

DC Comics published a prequel to Doomsday Clock in a Batman/Flash crossover called The Button, which is out in hardcover with a fancy cover that changes when you tilt the book. I enjoyed parts of The Button — writer Tom King's segments of the story, particularly a slow-motion battle between Batman and the ridiculous Flash villain Reverse-Flash, is laid out with King's customary attention to the rhythmic power of comics.

But The Button isn't just a callback to the Watchmen: it also homages the 1980s crossover Crisis on Infinite Earths, which suggests that perhaps there's even more of a callback to 1980s nostalgia in DC Comics today than Doomsday Clock lets on. It seems that every single book DC is publishing has to hearken back to its 45-year-old-male readership's childhoods in some form or another.

I can't really recommend either of these books, even though they're definitely appealing to a certain kind of reader. It doesn't really feel like there's anything new here, but unfortunately there are plenty of readers who might take that as a recommendation and not a criticism.

One Year of Reading Through It

It makes sense that an anniversary meeting should be reflective, and so our conversation was wide-ranging in subject matter. We talked about being tired of waking up to the continual assault of horrible news. We shared our techniques for staying sane. We thought back to some of our favorite and least favorite book club picks (The Righteous Mind was incredibly useful for most of us; Hillbilly Elegy was not.) We discussed what it means that Democrats are wrestling with the legacies of several high-profile sexual harassers, while Republicans are somehow absolving themselves of any responsibility in this age of #MeToo.

People talked a lot about feeling hopeless. And that's to be expected — this first year of Trump's presidency, with Congress and the Supreme Court tilted in his favor, was bound to make us feel powerless. But at the end of this year, as we tilt into 2018 and its midterm elections, we have to shake off that feeling of powerlessness and embrace our own capacity for change.

It's important to remember what matters. Sharing a meme on Facebook probably won't help the political situation at all, for instance. Donating some money to a congressional race in a swing district might very well make a difference. Calling your representative helps. Registering friends and family to vote will definitely create positive change. Remember to allocate time and resources toward positive change, and not just the actions that make us feel good.

Most of all, it's important to keep talking and reading and processing and sharing. I've learned a lot from Reading Through It; the books have educated me about history and culture and inequality and justice, and the book club attendees have taught me about curiosity and humor and open-mindedness. I'm looking forward to the club's second year, in which we'll chart a path forward.

If you haven't yet attended, I hope you'll join us for Reading Through It at any of our future meetings. We meet on the first Wednesday of every month at Third Place Books Seward Park at 7 pm. We'll be discussing Weapons of Math Destruction on January 3rd, and Economics in Wonderland: Robert Reich's Cartoon Guide to a Political World Gone Mad and Mean on February 7th. The featured titles are always 20% off at Third Place in the weeks leading up to the reading.

William Gass, one of the most challenging and brilliant writers of the 20th century, has died, Dalkey Archive reports. I will never understand why Gass's 1995 novel The Tunnel, about Nazism and academia and guilt and procrastination, is not considered one of the major books of our time, alongside its peers like Infinite Jest and Gravity's Rainbow and The Last Samurai.

My introduction to Gass was a hilarious quote from this Paris Review interview, which I'll share with you now:

If someone asks me, “Why do you write?” I can reply by pointing out that it is a very dumb question. Nevertheless, there is an answer. I write because I hate. A lot. Hard. And if someone asks me the inevitable next dumb question, “Why do you write the way you do?” I must answer that I wish to make my hatred acceptable because my hatred is much of me, if not the best part. Writing is a way of making the writer acceptable to the world—every cheap, dumb, nasty thought, every despicable desire, every noble sentiment, every expensive taste. There isn’t very much satisfaction in getting the world to accept and praise you for things that the world is prepared to praise. The world is prepared to praise only shit. One wants to make sure that the complete self, with all its qualities, is not just accepted but approved . . . not just approved—whoopeed.

#MeToo finally starts making a mark in the publishing industry

Paris Review editor and Farrar, Straus and Giroux editor Lorin Stein has stepped down amid charges of harassment. “At times in the past, I blurred the personal and the professional in ways that were, I now recognize, disrespectful of my colleagues and our contributors, and that made them feel uncomfortable or demeaned,” the New York Times reports Stein wrote in his resignation letter from the Paris Review.

Meanwhile, author Jennifer Weiner attacked the framing of Stein in the Times story, and rightfully so:

NYT piece on Lorin Stein's resignation ID's him as "champion of new talent, particularly women writers." In 2016, 35% of Paris Review bylines were by women. One out of 10 interviews was with a woman writer. https://t.co/zVLYlUxijQ

— Jennifer Weiner (@jenniferweiner) December 6, 2017

And New Yorker staff writer Alexandra Schwartz just tweeted a link to the Stein story and left this comment:

That was the sound of the first shoe.

— Alexandra Schwartz (@Alex_Lily) December 6, 2017

Hopefully, we'll see more harassers in the publishing and magazine industries lose their power. We've written many times on this site that the publishing industry is primarily made up of women, except for at the very highest posts: editors and publishers and executives still tend to be men, and that affects every other aspect of the industry. It's time to drive the harassers out and replace them all with women.

Book News Roundup: Wrath can be fun!

Town Hall Seattle is looking for artists and scholars in residence. But because Town Hall (the building) is being renovated this year and Town Hall (the organization) is branching out into other neighborhoods, they're doing something a little different. Each of the four neighborhoods that Town Hall is using as home bases during their Inside/Out Program — Phinney/Greenwood; University District/Ravenna; Capitol Hill/Central District; Columbia City/Hillman City — will have its own artist in residence. Those residents will then program Town Hall events within their communities, in exchange for a $5000 stipdend. This is a once-in-a-lifetime kind of thing. Submit to Town Hall by December 10th, okay?

Penguin childrens' book designer Giusseppe Castellano left the publisher under a cloud after being accused of harassing comedian Charlene Yi, who was pitching projects to the publisher. Castellano then released a statement claiming that Yi's complaints were "false." But Yi brought receipts:

Here you go: correspondence about business, your email asking me to get a drink after I asked for a response on my book, my response to you gaslighting me after you suggested having an affair several times, then you admitting it. May you never abuse your power or harm another. pic.twitter.com/PtW73DszHs

— Charlyne Yi (@charlyne_yi) December 4, 2017

Wow you're gaslighting me again?? Here's your email after I told you to think about your family and how disgusting it was that you were gaslighting me. pic.twitter.com/C3kZKUbEPg

— Charlyne Yi (@charlyne_yi) December 3, 2017

What were you apologizing for so many times? Quick, hurry, think of a lie. Throw me under the bus to save yourself!!! pic.twitter.com/smh6iUGKUZ

— Charlyne Yi (@charlyne_yi) December 3, 2017

Related: if you have experienced harassment in childrens' book publishing, here's a survey that's intended to help "get a handle on the scope of the problem."

Don't fuck with Joan Didion, because she will murder you with two words.

And Eileen Myles is taking none of your bullshit, either:

Oh shut up. https://t.co/bm8hdB7J4t

— Eileen Myles (@EileenMyles) December 5, 2017

Words written in anger, words written in ink

Published December 06, 2017, at 12:00pm

The hot takes said Ta-Nehisi Coates's reporting on the Obama presidency aids and abets white supremacy. Robert Lashley found something different in the words written on the page.

Looking for a holiday gift book? Richard Chiem recommends The Passion According to G.H.

Every Wednesday between Thanksgiving and Christmas, we're asking some of our favorite Seattle authors to recommend the books they're most excited to give as gifts this holiday. Our second author is short story writer and novelist Richard Chiem.

I recommend The Passion According to G.H., by Clarice Lispector, for that weird strange someone in your life. It's about a maid who accidentally kills a cockroach, and then goes through a stunning and hellish existential dreamscape. Almost every sentence is some kind of dagger, and she reminds me of Kafka but deadlier. Not for all readers, but I dare you watch this interview with her and not pick up all her books right away:

A fairy tale of New York

Published December 05, 2017, at 12:30pm

Seattle author Anca Szilágyi launches her debut novel at the Sorrento tonight. It's a gritty, realistic fantasy, a fairy tale set in a gutter, and the main character will take up residence in your head.

Natalie Diaz, John Freeman, and a pair of events for you to consider

Yesterday, I told you that Arizona poet Natalie Diaz is in town for a fantastic new series of events celebrating indigenous women writers called Poetry Across the Nations.

What I failed to tell you was that Diaz's first Seattle event this week is tonight at the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library. She'll be appearing in conversation with great literary editor John Freeman in a discussion about inequality and invisibilty in modern America. I interviewed Freeman a couple years ago, and I can tell you that he gives brilliant, thoughtful answers. I bet he and Diaz will have one hell of a fascinating conversation.

And while we're talking about Freeman, I hope you'll join me tomorrow night at 7 pm at Third Place Books Seward Park for the final Reading Through It book club of 2017. We'll be discussing Freeman's anthology Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation. It's a book that covers a lot of ground, from poverty to immigration to racism to homelessness. Basically, it's an opportunity to discuss any problem in America today, through the eyes of some of the sharpest writers of our time. Even if you haven't read the whole book, I hope you'll come out and join the book club tomorrow night. It's absolutely free, and the conversation will be hot and heavy.

Relish

It’s summer in Sanger, California,

and there’s a volcano

between my mother’s lips

as she stuffs me

into tiny shoes and a cotton dress.

Ashes powder my pointy bits —

nose, elbows, training bra.Instead of running in grapevines,

I sit in mahogany pews

at a Methodist church and stare

at the heavily blushed face

of my grandmother —

her gray head juts

out her coffin

like a matchstick from a box.She used to force relish

into tuna — I said

I didn’t like it, she said

I didn’t know

how to brush my hair

and even if I did

it wouldn’t brush right.I want to strike her face

against flint

and ash her body into a jar —

cover the condolences of strangers

with I never liked Nona

and she never liked me.

A year of great books, delivered to you

Phinney Books is one of Seattle's favorite bookstores. It's smartly and creatively curated, it's a delight to be in, and it's an active reading and gathering space — their door is always open to Seattle's literary community. They're sponsoring the site this week to let you know about a program that brings the spirit of the shop right to your doorstep: Phinney by Post, a monthly (or every-other-month) subscription service.

I don't know about you, but we get pretty excited at the prospect of having Phinney Books' expert staff hand-choose a year of reading for us. Take a look at the selections for the last couple of years and you'll see what we mean. Sign up for any version of the Phinney by Post subscription program — there are plans for every budget and taste, including an option for children’s picture books — and they'll make your snail mail special again.

Sponsors like Phinney Books make the Seattle Review of Books possible. It's how we pay our writers and promote great programs like Phinney by Post, and it's part of our commitment to make internet advertising 100% less terrible. We'd love to feature your book, event, or opportunity on the site. Reserve a date now.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from December 4 - December 10

Monday, December 4: Easy Speak Rainier Beach

Easy Speak is a series of citywide open mic nights with featured readings. Tonight, they debut the newest chapter of the ever-growing Easy Speak empire on the south side of town — Easy Speak Rainier Beach! The first reader is Seattle Civic Poet Anastacia-Renee, who’ll read for about twenty minutes. This open mic comes with music from the Jim O'Halloran Trio and “whatever noise you can fit into five minutes.” Jude's Old Town, 9252 57th Ave S, http://easyspeakseattle.com/, 7:30 pm, free.Tuesday, December 5: Daughters of the Air Reading

Anca Szilágyi’s debut novel is finally here! Szilágyi has been reading and contributing pieces to the Seattle literary scene for years now, and we’ve got great expectations for her first novel. (How is it? We’ll be running a review soon but — in short — it’s very good!) Tonight, join Szilágyi as she launches her book into the world from the swanky Fireside Room of the Sorrento with the help of her frequent literary partner in crime, Corinne Manning. Sorrento Hotel, 900 Madison St., http://hotelsorrento.com, 7 pm, free, 21+.Wednesday, December 6: Reading Through It

Every month, the Seattle Review of Books and the Seattle Weekly gets together to host a current-events book club at Third Place Books in Seward Park. December’s selection, A Tale of Two Americas, is a strange duck: it’s an anthology of essays, fiction, and poetry edited by literary tastemaker John Freeman. The book covers just about every kind of topic imaginable in post-Trump America, so tonight’s conversation will likely be a catch-as-catch-can potluck of civic nightmares, spotted with occasional moments of hope. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, December 7: Poetry Across the Nations: An Indigenous Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030. http://www.hugohouse.org, 7:30 pm, free.

Friday, December 8: Khizr Khan

In an election cycle fraught with shameful behavior, Khizr Khan stood out as a dignified figure — a man who understood the difference between right and wrong and wasn’t afraid to announce what side he was on. Khan’s new book, An American Family, details the many sacrifices his family has made for the sake of America. He’ll appear in conversation tonight with Crosscut’s Managing Editor, Florangela Davila. And just in case you needed a reminder that the world is a political dumpster fire, the listing for this reading warns, “For your safety and the safety of others, all guests attending this event are subject to a courteous screening and bag check before entry into the event.” Boo for all the assholes who threaten brave people with violence. Seattle University School of Law, 901 12th Ave, 7 pm, free.Saturday, December 9: Fantagraphics Bookstore Turns 11!

Georgetown’s own mecca of comic-book greatness is officially a tween today! To celebrate the first year of the second decade of the Fantagraphics Bookstore dynasty, Fantagraphics has pulled in some fine speakers: Dame Darcy will play music and read from upcoming work. Charles Forsman will preview some of the Netflix series he’s got coming out. And Frank Young will introduce his new book about famous American cartoonist Art Young. Plus: art, refreshments, and more cartoonists than you can shake a stick at, if you’re in the habit of shaking sticks at cartoonists, you big weirdo. Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore, 6 pm, free.Sunday, December 10: Till Chapbook Release and Holiday Party

Mount Analogue hosts the debut of this year’s edition of Smoke Farm residency’s chapbook, Till, with readings from contributors including Jennifer Brennock, Letitia Cane, Drew Dillhunt, Katie Ellison, Breona Gutschmidt, Nicole Hardina, Mark Lammers, Molly Thornton, and John Whittier Treat. The Seattle literary community doesn’t have an office Christmas party, but if it did, it would look a lot like this. X Y Z Gallery, 300 S Washington St, http://www.mount-analogue.com/ , 6 pm, free..Meet E. Lily Yu, this year's winner of the Gar LaSalle Storyteller Award

This morning, Artist Trust announced that Seattle writer E. Lily Yu is the recipient of this year's Gar LaSalle Storyteller Award. This is a fairly new award in Washington State's arts scene, but it's a mighty one — it pays $10,000 to its winner, with no strings attached. In 2015, Anca L.Szilágyi was the first Gar LaSalle recipient, and that prize money seems to have paid off; her debut novel, Daughters of the Air, is launching tomorrow night at the Hotel Sorrento. Last year's winner was the novelist Peter Mountford, whose The Dismal Science is a sophomore novel that is so good it will make you renounce the very idea of a sophomore slump.

Both Szilágyi and Mountford are writers of literary fiction, but Yu has a different pedigree: while she's published in literary outlets like McSweeney's and Hazlitt, she's also appeared in science fiction and fantasy publications like Tor.com and Fantasy and Science Fiction. A Clarion West graduate, Yu has appeared in multiple annual best-of sci-fi anthologies. You can read some of her short work by following these links on her website.

If you're the last human being on earth who is still snooty about sci-fi, Yu might be the author to turn you around. Her prose is weird and beautiful and striking. She's a unique voice, she has published some beautiful fiction in the past, and she will undoubtedly produce great works in the years to come. You'll want to be a fan of her now so you can say you knew her before it was cool to be a fan of E. Lily Yu. Yu was kind enough to talk with me over email about winning the Gar LaSalle Storyteller Award; hopefully she'll do a longer interview with the Seattle Review of Books in the future.

Congratulations! What was your response when you were told you'd won this award?

Joy. Astonishment. Amusement and embarrassment over my lack of faith; the phone call was a bit of a divine I-told-you-so. Then a sudden and overwhelming sense of peace. I'd felt anxious the day before, and that all went away as if it had never existed. It'll come back, of course, all the colors and tones of the human experience do, but for right now there's just peace.

May I ask what you're planning to do with the prize money? Is it going toward living expenses, or is it devoted to a special project?

Buying time. I'm buying two months and ten days with it. And I'm spending that time right now.

Do you think of yourself as a Northwestern writer? Does your regional identity figure into your work on a thematic level?

This is home. It was not always home, it might not always be home—that's in God's hands—but right now it is home in the deepest way. Like blood. Like bone. It has and it is and it will appear in my work.

That said, I am many regions. Most of us are. One crosses whole countries between Fulton Street and Harlem, but who would call themselves a Bed-Stuy writer?

The previous two recipients of this award have been literary writers. Do you think it's significant that this time it's going to a writer whose work can be classified as genre fiction?

Not particularly, but I am not best placed to know. I came to Seattle years after it made a name for itself as a hub for both literary and speculative fiction, so the intermingling of the two communities seems to me to be the most natural thing in the world.

Does that distinction—the literary and the genre—mean anything to you?

As much as fences mean to flowers.

Literary Event of the Week: Poetry Across the Nations: An Indigenous Reading

“The lives of Native women are not valued greatly in the Americas,” Arizona poet Natalie Diaz explains. This is not just a matter of feeling underappreciated; literal lives are at stake. “The rates of Native femicide in North and South America are astronomical, and also invisible in regard to mainstream media discussion.”

Part of the reason these lives are being snuffed out, Diaz says, is because Native women feel isolated and removed from the culture. “It is not often that we see positive and powerful representations and reflections of what is beautiful and strong and innovative about indigenous people, and especially indigenous women,” she writes in an email. With the help of the Hugo House and the Poetry Foundation, Diaz is working to celebrate Native women in the literary arts.

“I have been thinking a lot about the strong community of indigenous women artists and writers whose mentorship and friendship I have benefitted from greatly,” Diaz says. “I wanted to create a space where indigenous women's voices were regarded and value — to pay it forward in a way to some of the Elders whose work and friendships have made my own work possible.”

Now Diaz is ready to share that celebration with the world. It’s an ongoing program called Poetry Across the Nations, and it launches right here in Seattle in a multi-day celebration from December 6th to 8th. On Wednesday and Friday, Diaz will be hosting workshops for Native writers — find details at the Hugo House’s website — and on Thursday, December 7th, she’ll MC a reading of Native women poets at Fred Wildlife Refuge.

All are welcome at the Thursday night reading, which is free and will feature both Seattle readers and poets from across the country. The lineup is impressive: Celeste Adame, Laura Da’, Jennifer Foerster, Casandra Lopez, Sara Ortiz, and Cedar Sigo. Da’, Sigo, and Lopez have all been kicking ass at Seattle readings for quite some time; the three of them on a bill together should be practically lethal.

In the spring, Diaz will take Poetry Across the Nation on the road, with stops in South Dakota and Arizona already planned. But Seattle gets it first. If you’ve been outraged at the way Native voices have been silenced, ignored, and ridiculed by the Trump administration, here’s an opportunity for you to elevate and celebrate those voices. It’s up to all of us to witness Native women, to let them know that they’re seen, and welcomed, and appreciated.

Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030. http://www.hugohouse.org, 7:30 pm, free.