Help Desk is closed for Thanksgiving break

Cienna Madrid is on Thanksgiving break. The Help Desk will return next week. In the meantime, please send all your literary etiquette questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Your questions may be featured in an upcoming Help Desk column!

Portrait Gallery: Gillian Gaar

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

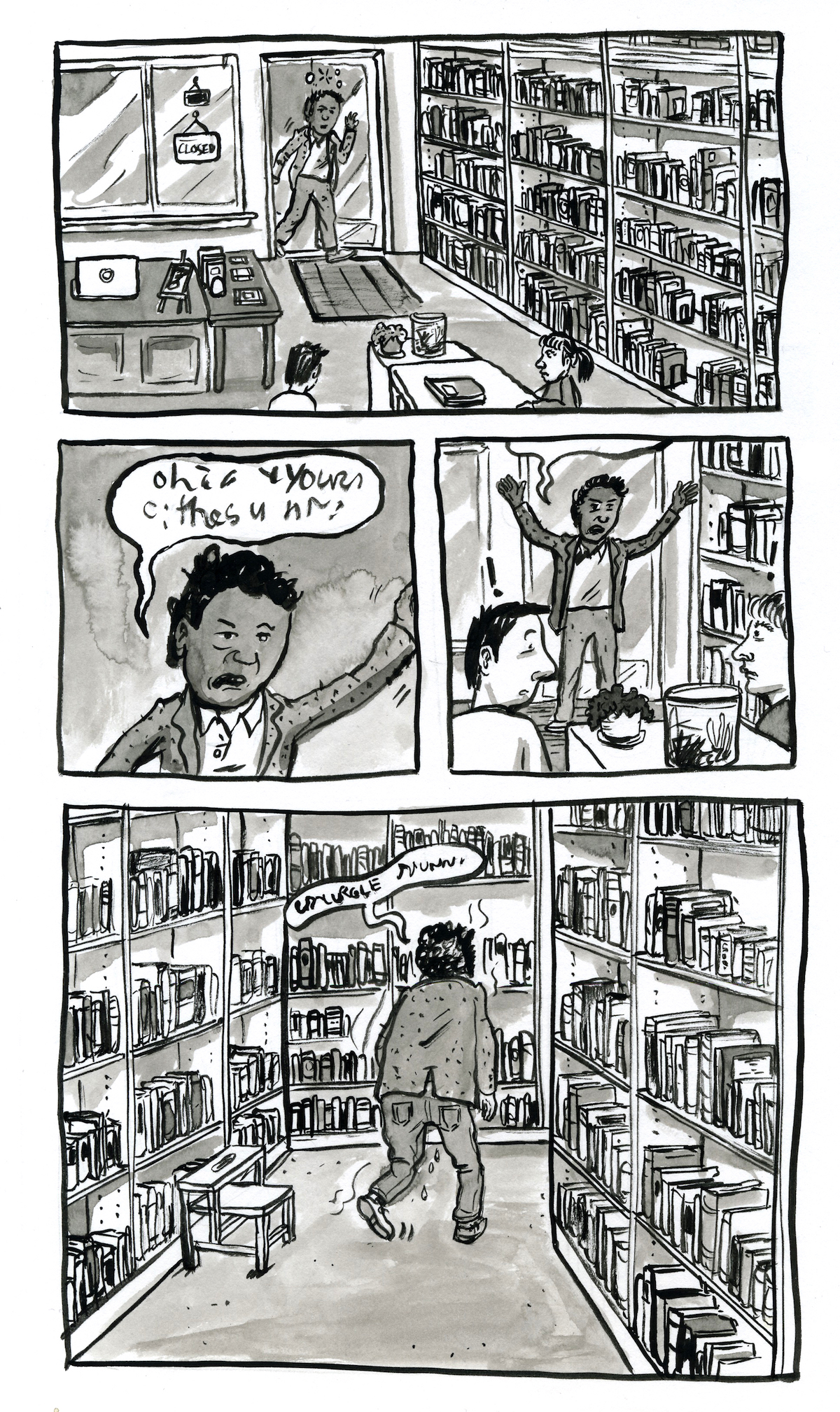

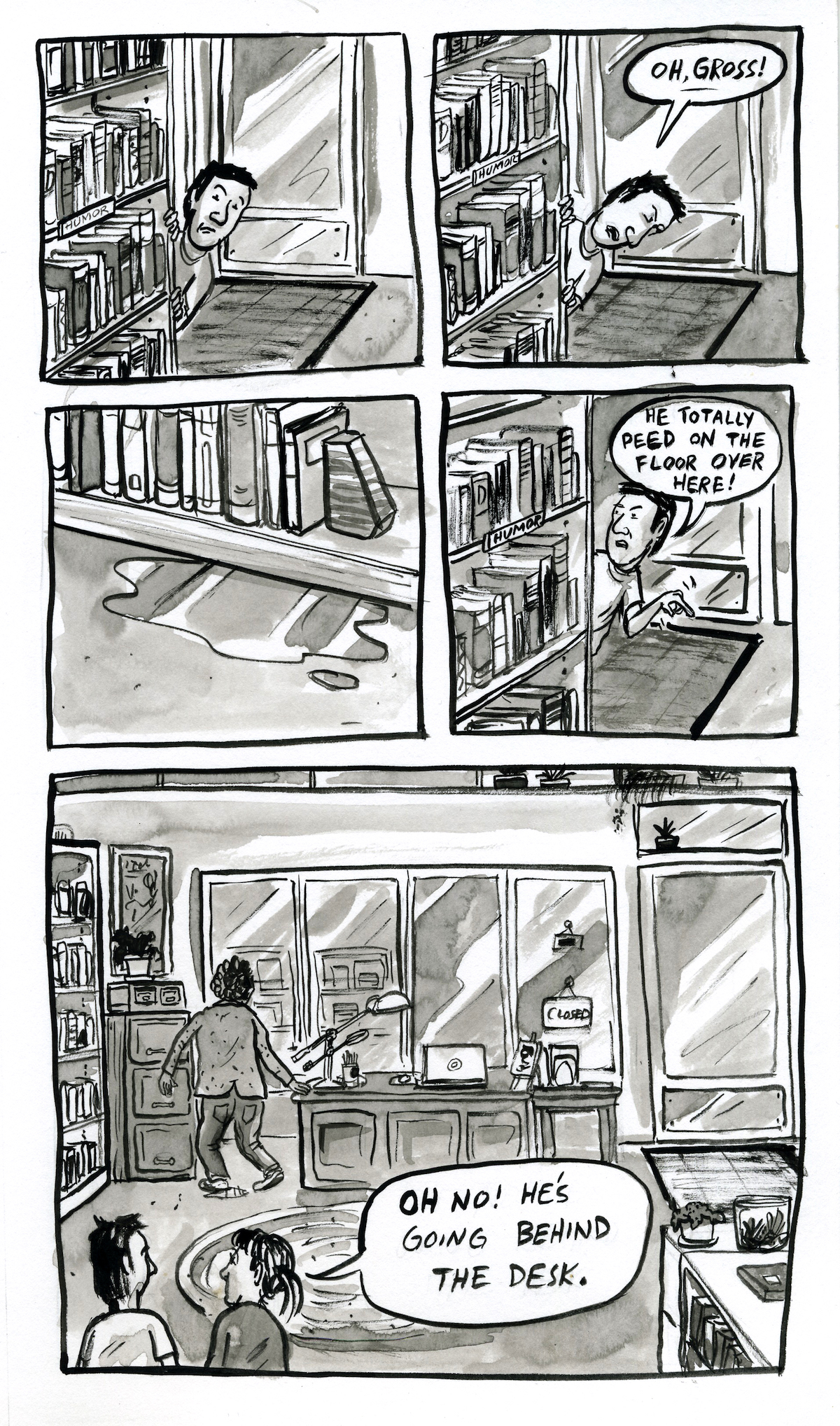

Friday, November 24th: Shabazz Palaces with Special Guest Gillian Gaar

Seattle hip-hop geniuses Shabazz Palaces are branching out and becoming multimedia moguls. Tonight, they debut their first-ever comic book, Quazarz vs. The Jealous Machines, with a signing and DJ set in Georgetown’s fabulous Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery. Expect some neat things to happen when comics and hip-hop combine. Along for the ride is Seattle-area music writer Gillian Gaar, who will be signing her new book Hendrix: The Illustrated Story.

Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore, 6 pm, free.

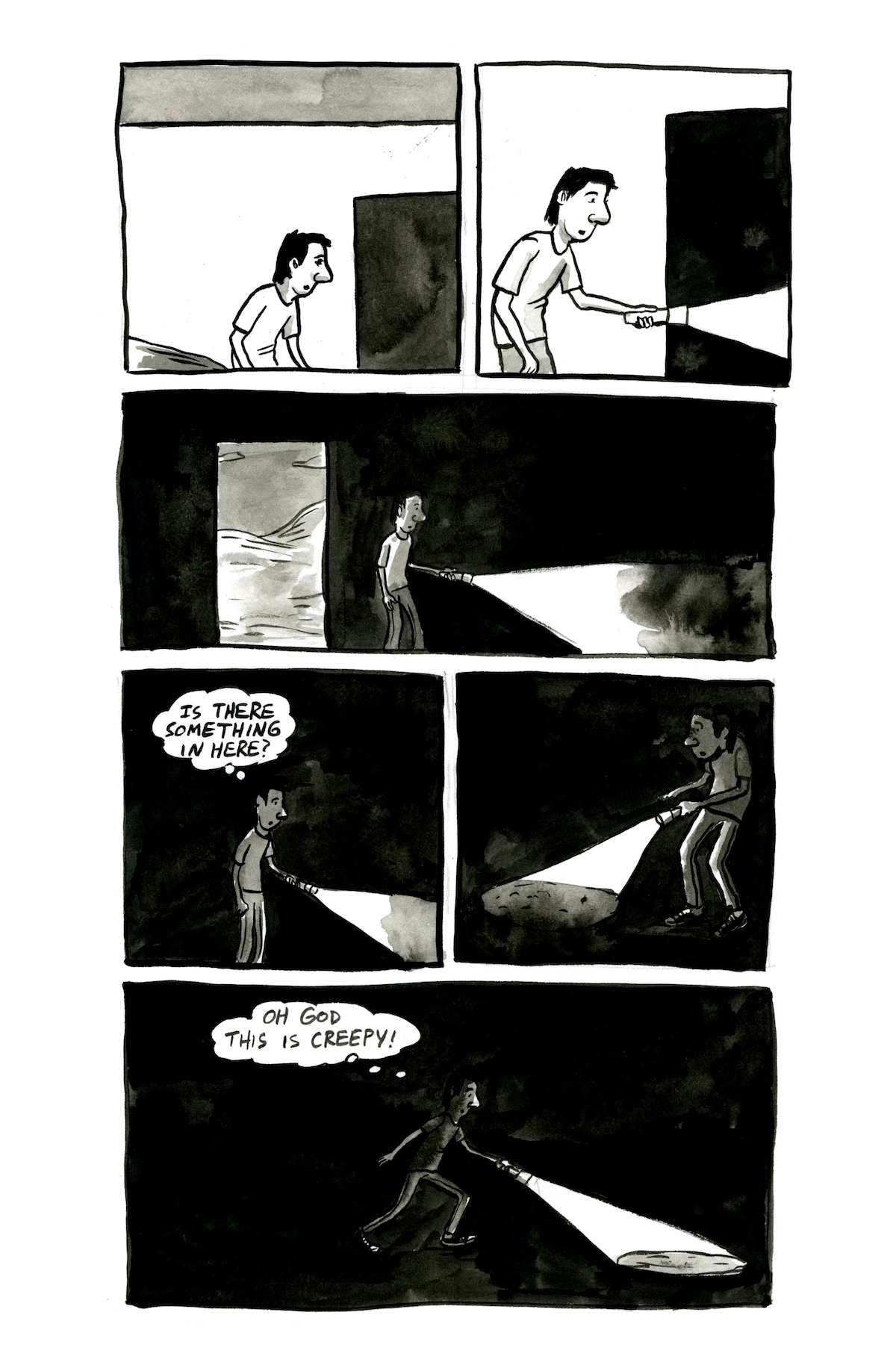

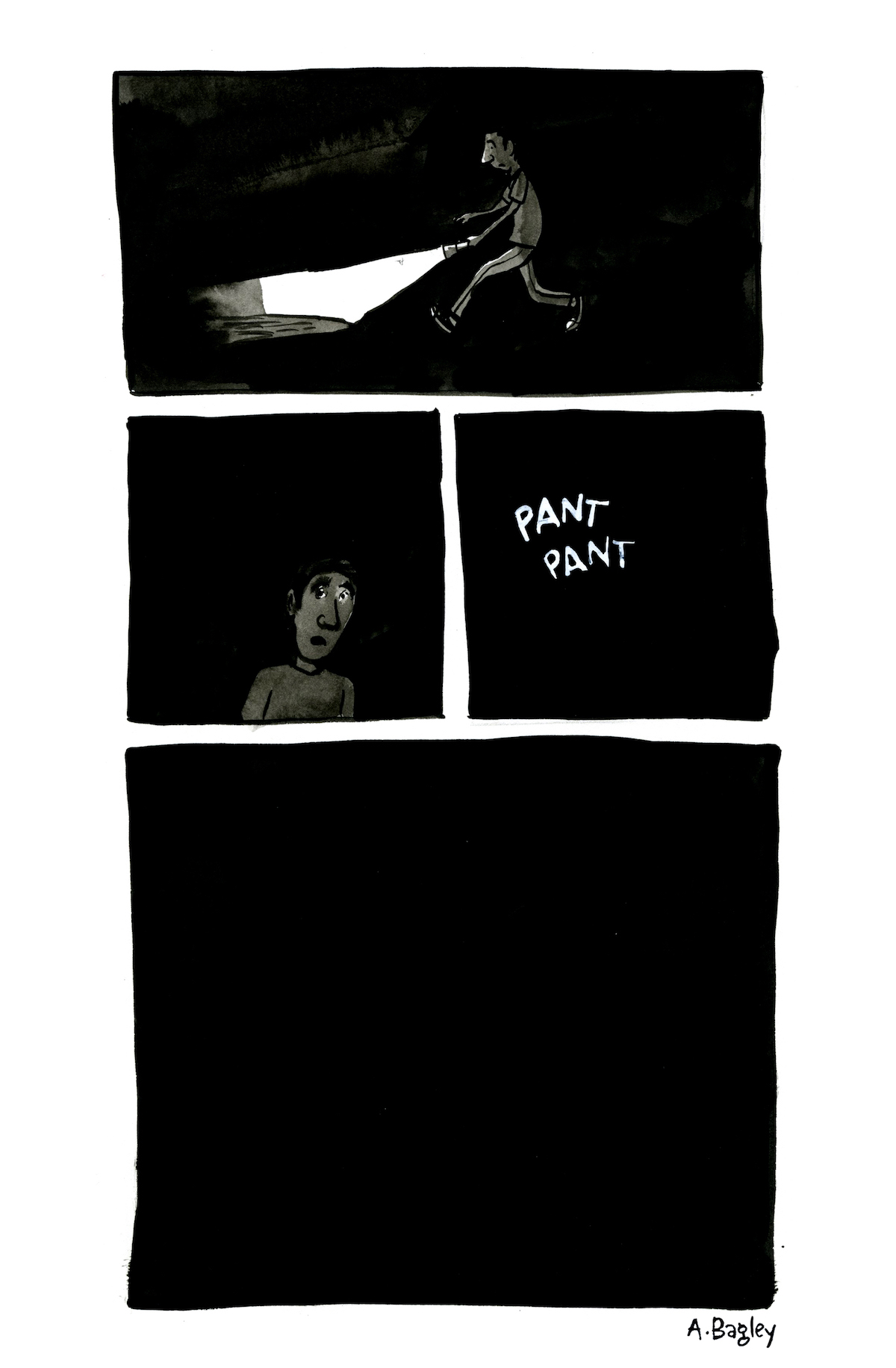

Morning Terror Nights of Dread

The Pacific Northwest is home to many unique eccentrics, but there was one character who, if you encountered him, you never forgot. He went by the name Symptomatic Nerve Gas, and no, this is not some kind of sub-par Vonnegut fiction. He was a real man, a Korean War vet, apparently, or Viet Nam, perhaps, or maybe not a vet at all, depending on who you believe — the narratives are mixed and told in different ways depending on when you met and talked to him.

I first encountered him on a city bus in Bellingham in the mid-80s. I was riding home, after putting my quarter in the fare box. This very solid looking middle-aged man came aboard, an army green duffel on his back, stuffed to the point of breaking. He dropped his bag to the ground and sat across from me on the sideways seats in the back of the bus. I'm sure I was reading, so paid him little mind.

Until the bus had left the station and I heard a little voice quietly say those three words, nasal, at the top of his baritone register:

"Symptomatic Nerve Gas."

I ignored him. Why would you look at anybody talking to themselves on a quiet bus? You would hope that it was a momentary glitch and they'd go back to being quiet.

"Symptomatic Nerve Gas."

Looking up, I saw his duffel had a manilla folder taped to it, and on the folder in black marker he had written those three words: "Symptomatic Nerve Gas."

I looked around, and other people on the bus caught my eye. Yes, we said to each other in a glance. Yes, this guy is really breaking a social contract in a minor way. We are all witness to it.

"Symptomatic Nerve Gas."

All the way home, every minute or so.

Apparently he travelled the Pacific Northwest, spreading his message. You can Google him and find reports from Bellingham to Eugene. Jack Cady wrote him as a character in his book Street, about a serial killer in Seattle. "People are first shocked into avoidance. Then, familiarity brings scorn, Symptomatic Nerve Gas has an important message, but no stage presence. He breaks no laws. People mistake him for a nut."

He must have liked something about Bellingham, because he spent quite a time there, over at least a few years.

Once, outside a punk show at this all-ages joint called the Vortex, where the bands would play 30 minute sets interspersed with 30 minutes of dance music, he held court.

He sat on a bench, and around him, punk teenage skaters sat on their boards while he explained what Symptomatic Nerve Gas was — a nerve agent made by the Vatican, spread in the candles they use in church. The Nazis also used it. A thick, messy, paranoid obsession ruled this man's mind, but he could talk about it in a disjointed dialog for hours on end. He was an evangelist, and his evangelism was based on trying to save the world from the evils of this horrid nightmare toxin.

I wonder if it was good for him, to have an audience like that, or if it fed his manic side? Was he a balloon that needed to let air out, or would talking about it ramp him up into unhealthy excitement?

Because I was not one to find mental illness ironic or funny — unlike some folks who encountered him in my group — I kept my distance. I found him unusual and therefore interesting, but also unnerving. I did write a song about him in my band at the time, which I'm glad there are no recordings of (that I know of). If I remember, it was just chanting the three words over and over again.

It was music that brought him to mind, after many years of not thinking after him. I was wondering about song loops, earworms, or snippets of music that get trapped in the head. What mechanism of the brain is there to reinforce this? Is it an evolutionary advantage, or a glitch in the operating system of humans that allows things to get stuck and amplified ad infinitum?

Likewise, go thoughts. One sign of being a progressive sort of person is not that you don't hear the horrible, racist, sexist intonation of default culture rattling around your memory pan, but that you know well enough not to squirt it out between the flaps of meat that make sound and language just because your brain thunk it. You know you are parroting the culture's response, and you know well enough that it is lies and you don't have to listen to that damaging bullshit.

But those little ghost whispers that want you to think something? Imagine if they were overwhelming. Imagine if you could never rid yourself of them. Imagine if they became your entire reality.

Last year, for our Thanksgiving essay, Paul Constant grappled with the election that pried free the last finger holding to sanity our world offered. 2016 relentlessly presented us with stark, impactful deaths, and one of those was of the death of being able to mostly ignore (if you are privileged enough) politics, unless you enjoyed not ignoring them. None have that luxury any more, and every day of this year has presented is a new battle, a new outrage. It's maddening, disheartening, and depressing.

And then, this rising moment overtook us. Like a wave bashing against the rocks as it gains purchase with the tide, women speaking out about their experiences with horrible men are starting to drown the old easy-to-toss-aside PR responses that led to no change. Men are being fired, quickly, and the apologies that once might have been directed towards the perpetrators for deigning to impute them are now rightfully turned towards towards women telling their stories.

This rising tide was buoyed by outrage that an admitted, gloating abuser, a confessed sexual predator and alleged rapist could take the highest office in the land, while the party that most espouses what they always called "values" has, at best, shrugged.

This is not a political essay at heart, but in thinking about Symptomatic Nerve Gas, I was reminded of the loops and ticks our president exhibits, his reoccurring nightmare cabinet of tinctures for soothing his confused, bloviating, leaking corpus of an id, his rancid corpulent ego, and his minuscule, weak, weepy, infantile superego.

He pulls out the same patterns over and again, throwing blame at people he beat, throwing credit to under-bed-monsters we thought had been swept out with the end-of-modernism trash at the close of the last century. His reactions to almost any event are starting to feel like a rubber reflex hammer on the kneecap, a hit and a jerk and he's talking the same lines he always does.

Trump has a bigger vocabulary than Symptomatic Nerve Gas did, but he's stuck in patterns just as pernicious. He's just surrounded by luxury and privilege, and protected by family.

I've been thankful lately for music. Music has played an important role in my life — it was the binder in nearly every one of my strongest friendships. To this day, knowing what music someone likes allows me to pull a quick Meyers-Briggs assessment — not to judge, mind you, but to understand them, to gain a quick bead on the type of soul that inhabits them.

As an adult I've come to realize that music has its limits; truly horrible people can like the same music as you, and I have to fight my default asshole inner hipster who wants to burn it all down when someone I don't respect declares love for music I do. That petty inner voice, that smaller, but still audible, cultural default, nearly ruined music for me.

I also go see almost no live music anymore — after working in guitar stores and playing live in small clubs for years, something broke inside me. Maybe it was an appreciation and attachment to what music meant. Maybe it was disappointment that my naive hopes about a career in music didn't pan out.

I elevated music too high, I thought it was everything — and for some of my friends it still is — but I realized that music is for me but a layer on top of my emotional life, a processing and distraction, but not a political force. It is magical, but it is also thin and not meaningful past the emotions it gives you access to.

In short, I thought too much of it, and in reckoning that music is less than I thought, I lost faith. Where faith was lost is found disappointment and resentment, of a type that it has taken me many years to best.

I keep playlists of good new release music I find each year. Last year's playlist "2016 2016 2016" had 97 songs. This year's "2017 2017 2017" has 385 and counting with a month left to go.

Is this really a strong year for music, or have I reconnected with music in a new way? Hard to know, but whatever the case, I pulled together a Thanksgiving playlist here of songs I'm in love with. I am grateful to them, to the artists who make them, and to people who care to share this experience with me.

They share something else in common, too, but more on that later.

I've embedded the songs below with Spotify because that service allows embedding, but here are the full lists:

The playlist starts with women.

Brooklyn's Shilpa Ray's "Morning Terrors Nights of Dread" echoes a thing we all feel, wishing our mental health were in a better place. "It's weighing down on me," she sings. "I lock my head between my knees, I can't breathe." Hello, 2017!

The mysterious masked Leikeli47 turns the title of her song "Miss me" on its head, when you realize it's not about feeling the lack of someone, but an instruction: "Miss me with the bullshit."

The Regrettes are teenagers from Hollywood whose fearless feminism is punky and smooth as a teenage girl group, and whose harmonies and soaring stair-step melodies always make me smile in such a huge way.

Miya Folick, as all of us, is having trouble adjusting.

Actress and musician Charlotte Gainsbourg returns with a rhythmic loping piece that imagines a marriage run dark.

Lilly Hiatt, who obviously learned great lessons from her dad John, takes us back to the beginning of 2016, when everything seemed to start dumping, with her song "The Night David Bowie Died". "I wanted to call you on the night David Bowie died, but I just sat in my room and cried."

Canadian singer Gabrielle Shonk tells of a man (with that voice! My god, that voice) who deserves being called out for his bullshit. "You cheat and lie causing pain with no sense of regret."

The Paranoid Style is a band with super-intelligent lyrics, like Costello or Game Theory, and took their name from a famous Richard Hofstadter essay, here they turn male gaze into a Dedicated Glare about the intricacies and boredom of adult life.

Sylvia Black goes feminist witch, and torchy nightclub singer, with her meandering relaxed bass style (she was a studio musician, so has chops for weeks) and haunting vocals.

Moderate Rebels want to liberate. "Who's using power? And who cares? The dead and the living."

Kevin Morby is the first man on the mix. He obviously listened to a lot of Television, and the creamiest guitar tone is in his song "City Music".

Tricky and Asia Argento (she who was chased out of Italy for speaking her truth about Harvey Weinstein) get almost unbearably intimate.

UNKLE invited Mark Lanegan to croon about "Looking for the Rain" in this great, swelling, orchestral track.

LCD Soundsystem take on our modern world "The old guys are frightened and frightening to behold".

Dams of the West finds Vampire Weekend's drummer Chris Tomson accounting for his life. "I don't want to be perfect. I just want to fix the fixable things."

Kendrick Lamar looks at literal and figurative DNA, exploring black culture and history, as well as his own place inside that larger whole.

60's garage rockers Flamin' Groovies show that rock doesn't have to age, but are wondering if maybe we've reached the "End of the World".

I'm contractually obligated, being in the Pacific Northwest, to put a Guided by Voices song on this list. Thankfully, it's really good about how we lionize old music.

Chicago's Twin Peaks sing a song about picking up a guy at a bar who is drinking his breakup away.

Low Cut Connie want to start a revolution, of sorts, but it may just be a boogie-woogie one.

And finally, Portland's Kyle Craft has an amazing voice, a kind of twenty-first century locally-sourced Jeff Buckley, and this cut, from his next-year's Sub-Pop release, is sure to get some attention.

I learned a trick with music that saved me. It's to accept the song in the moment you are experiencing it. Let it unfold, as it is, and when it's gone, move on to the next song without holding too tight. Don't ascribe any meaning past the pleasure of the moment.

Except, that is, when a song gets stuck. And this is my confession: all the songs above in that playlist are ones that have, at one time or another, gotten stuck in my head this year. They are ones that have become earworms, that have informed my year at various points. They have been hard to shake.

None of them have infected me to such a degree that they become singular, the only thing I might listen to. Some, however, have spent weeks rattling around, cooing, singing at me, trying to inform me, but when I turn to find meaning, all I find is a sly melody or simple line.

Some find meaning in simple lines: prayers repeated, mantras chanted, songs sung over and again. A repetitive line may become an expression of an acute mental illness. In a different brain they may become simple metaphors to explain an overwhelmingly frightening world, whether they originate in that brain or on a television program designed to booth soothe and terrify simultaneously. Morning terrors nights of dread.

I think about Symptomatic Nerve Gas sleeping on the street on a cold night. I think about our president watching cable news and tweeting at 3:30am. I think about a young woman sitting with a guitar, trying new melodies and scribbling down lyric snippets until it becomes coheres into a song.

I think about what gets stuck in our heads and how we can unstick it. I'm thankful we have the opportunity to even try.

Don't forget Small Business Saturday!

Tomorrow, of course, is Thanksgiving. The day after that is Black Friday. Don't shop anywhere on Black Friday; it's a mess out there. But on Saturday, you should go shop at your favorite small business, because it's Small Business Saturday. Small businesses are essential to local economies; studies have shown that while only 14 cents of every dollar spent at a chain recirculate through the local economy, nearly 50 cents of every dollar spent at a small business stays in the local economy.

Your favorite small businesses are probably bookstores. And a lot of local bookstores are celebrating Small Business Saturday with special events and deals. Here are some of the treasures you'll find:

Bainbridge Island's Eagle Harbor Book Company is hosting authors, hot cider, and prize giveaways.

Edmonds Bookshop is offering cookies, autographed books, and "a gift of Jefferson flyer with purchase," with the caveat that "you'll have to come in to see what that is."

Magnolia's Bookshop is hosting author Molly Hashimoto, along with free treats and tote bags.

The Neverending Bookshop in Bothell is hosting trivia all day and a reading from local fantasy author James D. Macon.

Page 2 Books in Burien is hosting authors Elise Hooper, Kelly Jones, Sonja and Jeff Anderson, Ann Haywood Leal,and Michele Bacon.

Queen Anne Book Company is hosting authors, treats, and a ton of giveaways.

Ballard's Secret Garden Books is hosting children's book authors who will serve as guest booksellers all day.

At all the Third Place Books locations, if you spend $50 or more, you'll get a $10 gift card in return.

Talking with Reza Aslan about why we're wired for faith and how farming was a bad bet for humanity

Reza Aslan's new book God: A Human History is a remarkable document. It lays out the entirety of human's relationship with the divine, using athropological and archaeological documentation. From pantheism to ancestor worship to monotheism, Aslan examines the way that a concept of a higher power has evolved right alongside human civilization — and also helped shape our modern world. Aslan was in Seattle last week with Seattle Arts and Lectures. We spoke on the phone shortly after his arrival in Portland for the next reading on his tour. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

I’m an atheist but I've always been very fascinated with belief and the way that you approach this book. I thought it was really informative for the purposes of talking with people about faith — and not just religious faith. At my day job, I work in messaging and political economy. And I’ve found that when we talk about raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, for example, people would respond, 'well, you can’t pay $15 per hour because the market says they’re not worth $15 per hour.' The market is a creation of people, and other nations have much higher minimum wages than we do here in America so there’s proof that it can work, but once people offload it to this inhuman, unknowable force —this market — there’s a barrier. You hit a wall in your conversation, and it seems insurmountable. Has your work with so many different religions taught you anything about talking across that wall?

If you think of a faith as a kind of worldview then it's understandable why occasionally it becomes difficult to actually have conversations. This wall that you're talking about — essentially, you're talking about two different perspectives, two different points of view. And often it's not that you are arguing over the merits of some kind of point, but what you're really doing is talking about two different ways of seeing the world. And so those kinds of conflicts sometimes come naturally.

Part of what I try to do, not just with this book but most of my works, is to try to reframe the conversation and to redefine certain terms. For instance, you call yourself an atheist, which I imagine means that you don't believe in God. But I do think that in order to actually have a conversation with you, we'd have to first talk about what you even mean by God, because it's very likely that your definition of God and my definition of God are vastly different from each other — and so having that understanding would mean that you and I perhaps are much closer in our points of view than we actually thought that we were.

And particularly when you're talking about faith issues, we have this weird perception that we all mean the same thing when we use this most complex of words, and so often the arguments that we find ourselves having dissipate once we start with this fundamental question of 'what do you mean? What is your perspective?' That's something that I try to bring to all the work that I do.

One of the things that I really enjoyed about this book was the way you embrace the ambiguity of the anthropological record. I think about that hackneyed idea of what would happen if an alien anthropologist found our ruined civilization in the future and if they only had access to one site, it would change their understanding of our faith. If they found a church, they would imagine us as a monotheistic religious culture. If they found a multiplex, they might think that we were a pantheistic religion worshipping superheroes. And if they found Washington DC, they might think we were big into ancestor worship. Do you think about what you’re missing when you look back on the past?

It’s a fun game to play. The difference of course being that we are products of a written culture, and once you start writing things down, those things stay forever. When we're talking about religion, however, and particularly when we're talking about prehistoric religiosity, which is where my book begins, you are talking about a preliterate culture and so that makes it much more difficult to draw conclusions with any measure of certainty.

We do have an enormous amount of material evidence at our disposal when trying to talk about things like the origins of the religious experience. We have at our disposal temples and idols and the spectacularly painted caves that bear remarkable signs of ritualistic thinking. And so we can look at this material and we can give our best guess as to what it means and how it functions.

But before the advent of writing, we are essentially shooting in the dark. What we have going for us particularly in my field of religious studies is that we can combine the anthropological and archaeological data. We can use what we know about sociology in order to draw certain conclusions and we can make pretty good guesses. But in the end, they are guesses.

In the book, you refer to the advent of agriculture as a net negative for society, and I was wondering if I could ask you about that, and maybe your perspective on how that has shaped human history.

To begin with, this is now more or less the consensus view. The traditional view was that after tens of thousands of years as hunter-gatherers, we began to plant our food and domesticate animals as a means of ensuring a greater food supply, and that doing so resulted in more stable food supplies and also in more calories, more food. And that allowed us to actually settle down and then create civilization, and then, of course, history as we know it.

Well, unfortunately, that traditional view just doesn't hold up any longer to the archaeological evidence. First and foremost we now know that we human beings had settled for thousands of years before the rise of agriculture. So that upends the notion that we settled down because we started planting — now, it turns out that we settled down for quite some time before we ever thought to start planting. So that in and of itself had to have to shift the way that we even think about why we started planting.

And then secondly we now have ample evidence to indicate that far from creating a surplus of food, the agricultural revolution actually diminished our food supply — and quite dramatically. It provided far fewer calories, far less protein, and if that weren't enough, it actually introduced a whole host of ailments and diseases that were completely new to the human condition. The great Israeli historian Yuval Hariri has this great line where he says homo sapien skeletons were simply not evolutionarily designed for farming. That's just not what our bodies were meant to do. He refers to the agricultural revolution as history's greatest fraud.

Now this idea that the agricultural revolution was not an advantage to human beings raises a more fundamental question which is: why, then, why did we start doing it? Why did we start farming, knowing that a bad crop would result in the deaths of everybody in the village? Why did we start domesticating and penning animals, knowing that a disease in one of those animals would wipe out the entire herd and kill everybody in the village? Why did we do all of these things, when it required far more effort and work than hunting and gathering did, for far fewer calories? Why did we do it? It makes no sense.

There have been a number of attempts to answer that question, from environmental changes to the thinning or extinction of herds — none of which have been borne out by the evidence to date. One of the more innovative answers to that question happened to do with the institution of religion. And what I mean is, the movement from the prehistoric animism that fueled our ancient ancestors to the establishment of temples and institutionalized worship — it was the institutionalization of religion that led to the settlements, to the idea that we actually settled down and stopped wandering.

And then once we settled down, that that caused the slow move towards experimenting with agriculture and with domestication. Again, this is one of those things where we're giving our best guess. We're looking at the evidence that's available to us, and we're trying to interpret it as much as possible.

But I think that the reason that there is an enormous amount of enthusiasm for that particular interpretation of 'why agriculture?' is because all the other answers don't work. So much of what this is about is simply ticking off things that don't make any sense or that don't fit with the available data and seeing what's left.

We do know, of course, that the earliest experimentations with plants and the domestication of animals took place in southeastern Turkey and in the Levant area. These are the earliest examples of settled communities, and we also know that [these regions hosted] the earliest expression of institutionalized religion, and that those things really affected each other. And so the theory is that it was in fact the advent of hierarchical institutionalized temple-based religion that resulted in the need for the transition to agriculture, despite the fact that it was not a good bet on the part of humanity — that it did not lead in those first couple of thousand years to more food or a more stable supply.

And by the way, part of the reason why I think people even people who don't study religions gravitate toward this theory is that the one thing that we all know about religion is it makes you do things that aren't necessarily helpful. The thing about religion is that you do sometimes irrational things in the name of religion and the you know the agricultural transition was by all accounts any rational thing.

So in a way, religion also established the inequity that we still see today?

You know, the standard sociological answer to this is when we went from wandering to settled, being settled allowed for the accumulation of wealth and the disparity in society in a way that wandering would not allow. The nomadic lifestyle doesn't really allow for the accumulation of wealth, or the stratification of society. Settlement does. And if you think that settlement was a direct result of certain religious changes that took place, then yes, once again religion becomes the culprit for the sudden disparity in society.

I love your example in the book of the talking tree — the theory that we can accept one or two divergences from what we know, but that if you keep adding unbelievable ideas, you reach a breaking point.

This is a fascinating theory — and it is a theory, but it's a pretty good one. It was first developed by a cognitive anthropologist by the name of Pacal Boyer. And what he was trying to figure out was a simple question: Why do some religious beliefs stick and some don't?

Obviously, he's a scientist so the answer that is often given, which is ‘the ones that are true stick, and the ones that are false don't’ just doesn't work for him. And so he began to do these very interesting studies about how our brains actually hold onto information, and particularly when that information is anomalous in some way. Why do we hold on to it? How do we hold on to it? When do we get rid of it?

And what he discovered was exactly what you say — this thing that has been now dubbed the minimally counterintuitive concept. The basic theory is that when the mind is confronted with something that is only slightly abnormal, something that that essentially violates the core function or characteristic of a saying only slightly, there is something about the brain that holds on to that idea, that anomalous information much more so than if a thing is too anomalous.

So the example that I gave in the book is a tree that talks. A tree that talks is only slightly anomalous. It's the kind of thing that the brain holds onto and is more likely to pass on. But a tree that talks and also has the ability to be invisible and also can move from place to place — now you're violating far too many categories of the idea of a tree, and the brain simply doesn't have the ability to hold onto that. [Boyer] uses this cognitive theory to explain why some religious beliefs stick around and others do not. It’s a really fascinating idea.

Of course the thesis of my book, the point that I'm trying to make, is that of all these minimally counterintuitive concepts that have ever existed in human history, the one that is most successful is the idea of the superhuman — the human who is altered in some slight way. And that where our conception of the divine arose, is this notion of a person who has shifted in a slight way, is given a certain kind of power. That is an explanation for how this natural impulse towards transcendence — towards that which lies beyond the material realm — is something that is part of our cognitive process. It's who we are, it’s how our brains work: that natural impulse often becomes actualized or concretized in the form of a divine human, or a human who is divine, because of this minimally counter-intuitive concept that arises in our brain.

It seems to me to be an exaggeration of something that’s a standard part of the human experience. Your knowledge, your experiences, make you special — kind of a superhuman. That’s why we contacted your publicist for an interview and why we’re talking. Everyone does something special — you know, I make a pretty okay chili. So is this search for the supernatural a recognition of us as we are or is it a desire for more? Is it aspirational, or is it a reflection?

It’s a reflection, it's an innate compulsion. One thing that I make very clear in the book is that I'm not making an argument for the existence or nonexistence of God. That's not an argument I am interested in having — mainly because there is no proof either way.

What I am interested in is how we have expressed faith. It is deeply embedded in this cognitive impulse that you were referring to, this innate unconscious compulsion to humanize the divine — to essentially project one's own personality, one's own emotions one's own virtues and vices and strengths and weaknesses and biases and bigotries upon the divine.

What’s truly remarkable about this impulse, and why I think it's just a function of our brains, is that even atheists do this. When you say to someone who is a you know an atheist, who doesn't believe in God, studies show that when you ask that person to then describe what they mean by God, they do what believers do. They begin to describe a kind of divine version of themselves. They begin to talk about a divine personality who looks and feels and acts and thinks very much the way that they do. So it doesn't matter whether you're a believer or not, it doesn't matter whether you are aware of it or not. The fact of the matter is that most of us when we think of the idea of God, what we do is we think of a divine version of ourselves.

You have a few passages in the book where you write about soul, and I thought some of the passages seemed to be in conversation with Lesley Hazleton’s book on agnosticism, and I was curious if you had read it or if if that was something coincidental.

I have read Lesley's book — I think I actually even blurbed it — but no, that's not in in conversation with anyone. The issue is that we were born with this conception of substance dualism, this innate notion that there is a distinction between the body and mind. What that means, nobody knows — it doesn't prove God, it doesn't disprove God. It doesn't mean that we are believers and we have to learn to be unbelievers. We don't know what it means, but it is a fact, and studies have routinely pointed this out. So it must be part of again our cognitive impulses, must be just a thing that happens in our brains. What I'm interested in, is what that actually means and how and how to make sense of that.

Evolutionarily speaking, we don't have a good answer for the universal belief in what is come to be called the soul. You can call it what you want: you can call it the psyche if you want to, you can call it Brahma, you can call it whatever you want, but we all mean the same thing — this kind of spiritual essence, if you will. It's universal. It exists in all cultures, in all religions, and throughout all time. And we don't know why! There isn't a good reason to explain this innate sense. And so I go back to where I began the book, which is ultimately it's just a choice.

It’s a decision on the individual's part to give that fact some kind of meaning. And you could be someone who says ‘it's just an accident, just a meaningless cognitive blip.’ Or you could be someone who thinks that it's not just on purpose, but it's by design: it's who is how we are made it's who we are and we're supposed to have that that feeling, that sense of innate spiritual essence. We’re back where we started, right? It's up to you! There's no proof either way.

But I do think that at the very least coming to an understanding of these things is a good way to start a conversation between people, between believers and nonbelievers, and between believers of different religions.

Book News Roundup: Apply now to be Redmond's Poet Laureate

Applications for the next Redmond Poet Laureate are due on December 15th. The selected poet will get $5,000 per year in artist fees and $5,000 per year in project materials.

These maps Kathy Acker drew of her own dreams are simply gorgeous.

The quest to create the ebook version of marginalia has yet to truly break new ground. Liza Daly has some thoughts on that.

Some reflections from Amazon staffers as the Kindle turns ten. The claim that Kindle “really was about the content" makes me shudder. Books are not content. Content is meaningless chaff you shove into the blank spaces of a website. Books are books. Please make a note of it.

Every city a mystery

Seattle author Juan Carlos Reyes’s novella A Summer’s Lynching begins with a city:

After all, there will always be places on Earth where elevated things happen, where few people call each other by name, where voices sprinkle across pavement and seep into cracks, where stories are codified in the song of humming air conditioning vents and whistling manhole covers, flooded gutters and opening soda cans, aging Camaros and nagging door bells, store-light gnats and encaged dogs, pigeons smothering pavement in shadowy monsters and ten year-old littering sidewalks, and near endless repair projects that, in cycles of upended sewers and streets, feign renovations that never improve a city.

The voice in Lynching is noirish — that gritty coating on everything, that list of ugliness — but it’s a noir at an angle, like a cheap detective novel swallowed up in existential dread. Like a detective novel, the plot centers around a dead body, and how it got that way. Also like a mystery, the narrative is focused on the systems surrounding the death (police, the courts, all the different operations that the city needs to function on a daily basis.)

But unlike a mystery, Lynching isn’t really interested in who killed Isidrio Rafael, the corpse in the boiler room. It’s more interested in what happens after a tenant in Rafael’s building finds his body hanging in a common area. The book’s second chapter is narrated, in part, by Rafael’s neighbors. “Too many of us crowded the boiler room archway entrance, pressing into each other to see the man’s face, his hands, his feet,” they explain.

The perspective keeps shifting from one place to another in the city, and the narrative drifts further and further away from Rafael’s death. It’s like Lynching is the story of a haunting, told from the ghost’s perspective. As the novella unfolds, its interest in the specificity of narrative fades. Our attention wanders around the city, floating just above people so we can observe them from the air, a slightly distant ghost.

Lynching visits seats of power and utilities — one chapter is set at the power company, another in a church, another in a nest of bureaucrats. They’re all affected by the murder in one way or another. The city that Reyes builds alternates between interested and disinterested in the murder. It’s kind of like this:

Silence inside a library always precipitates a clamor outside of it to where the sound of the whipping city banner frantic on its flagpole is as loud and screeching as the brakes on a passing bus.

The less a city’s system is involved with the murder — a high school, say — the higher-pitched our curiosity becomes.

In the end, the city that Reyes builds is a lot like our own: it’s too big to comprehend, but too small to truly lose oneself in. In a city, nobody is really a stranger to anyone else. We’re all interconnected in one way or another, even if we’re cloaked in anonymity. If you stay in a city long enough, the body in the boiler room will likely belong to you.

Inside/Outside

The cantaloupe sits

on the counter like

a little moon

swatted

off its course.Outside, grassy

undertones

and modest navel,inside, a wall

of pale orange fruit

and inside that

a child's night terrorof seeds and guts and string.

It is no matter:

The kitchen has

its own astronomy.

The instant the cutting edgepierces the rind — flesh

yielding to steel —the gig is up.

We simply eat.Outside the rain

arrests itself. A false sun

flourishes for the afternoon.

Inside his busthe busdriver sighs

ignoring if just

for an hour, the terrible

pair of pants

knockkneed and

abandoned in

the empty seat.How to hold it

all together: the violence

of the harvest, the embarrassment

of the blade. In his heartof hearts, the buzzard

knows he is digestible.

He scans the plain:

Too much wild life.He shakes the daylight

off his wings

and waits for the earth

to cough up the fruit,

for the night to bring

the knife.

You can tell a lot about David Sedaris from the edits on his Wikipedia page

Last night at Benaroya Hall, I introduced David Sedaris for his annual reading. What follows is my prepared text.

Hello! My name is Paul Constant and I’m a cofounder of the Seattle Review of Books. Before we begin, I want you to share a message with you from the very bottom of my heart. Here it is: Turn off your fucking cell phones.

I also want to let you know about an amazing opportunity. Last January, David Sedaris did a weeklong series of workshop performances at the Broadway Performance Hall. He was editing and refining pieces from his magnificent diary collection, Theft By Finding. I think that those performances were all that got me through the week surrounding Donald Trump’s inauguration; without them I would have stayed at home in my bathrobe and cultivated a thriving blackhead farm on my nose. The readings were funny and informal and they provided a fantastic window into his process.

And just as those sold-out shows meant a lot to Seattle, apparently Seattle meant a lot to David Sedaris, because he’s coming back this January for another weeklong stand at the Broadway Performance Hall. He’ll be workshopping his upcoming book of essays, Calypso, which means you’ll get to experience his book before everyone else. Every night of the week will include a reading and an intimate question and answer session, but no two nights will include the same pieces, which means you could attend more than once and never see the same show twice. I highly recommend that you attend.

Okay! Now it’s time to get tonight’s reading going.

Introductions are a funny thing. You already know why you’re here, so you don’t need me to tell you who David Sedaris is. If you’ve read his books before, you know that he’s knife-in-the-ribs funny and slyly compassionate. If you’ve seen him read before, you know that he’s literally a world-class reader of his own work, by which I mean there’s a very good chance that you are right now about to watch the best reading in the world tonight.

When called on to do introductions, a lot of people simply visit Wikipedia and copy down a list of accomplishments and titles. They then repeat those names back to the audience with all the life-affirming energy and unbridled enthusiasm of a hostage video. But I’ve done a lot of introductions in my time, and I’m here to tell you a secret: Wikipedia sucks as an introduction resource. In fact, you can learn more about a person by reading the edits to their Wikipedia page.

In case you have an active social life and didn’t know, allow me to explain: it’s possible to read every single edit that’s ever been made to any Wikipedia entry, and to see the conversations between the thousands of volunteer editors who oversee changes to the site. I spent hours poring over Sedaris’s page as research for this introduction.

The first noteworthy edit to David Sedaris’s Wikipedia page was in July of 2005, and it was written by a user named Chrisjamescox. Mr. Cox noted that he “Removed ‘satirist’ [from the entry and] replaced with ‘humorist’.” He went on to editorialize: “He is not a satirist! He doesn't comment with disparaging humor ('humour' in Brit. Eng.) on current events and trends. He writes about his family.”

Later that same year, a user named Moncrief asked, “How is [Sedaris] a Chicagoan?? He lives in France and is from North Carolina. If he's a ‘Chicagoan’ somehow, it should be explained in the article.” Someone else would later add, “he’s not jewish. he’s half greek/half protestant.” The next year saw a number of edits from a Wikipedia user named “Can’t sleep, clown will eat me.”

A bunch of notable additions came in 2007. One user wrote proudly that he “Added mention of [Sedaris’s] drug use.” May of 2007 saw additions of the words “expatriate” and “homosexual” to the page.

So additions are crucial, but you can also tell a lot from the deletions. “Removed the part about [Sedaris] speaking at the University of Arizona as it's not notable in any way,” one user wrote in 2011. (My apologies to any University of Arizona alums we may have here tonight.) User Jamend8 in 2012 writes that he “Removed France as Sedaris' ‘country of origin.’ He was born in the U.S.” An editor named Frosty protested a change by claiming that “I understand that this might seem strange, but the article claims [Sedaris] is known locally as Pig Pen.” MelonKelon responded, “That may be true. It's a nickname of sorts. But it is not a notable name, nor is it an alias he writes under.”

Word choice in Wikipedia articles is very important. Lee Bailey commented with disdain in 2007 that “a ‘humorous essayist’ is a humorist.” SergioGiorgiani writes that Sedaris’s speech impediment wasn’t “cured at all. He specifically mentions how his speech therapist left without having accomplished anything but making David avoid the letter S.” Someone else writes with palpable exasperation, “I changed Infoboxes: The guy was a writer and comedian, not a scientist.”

It goes on. And on. There are something like 1500 individual edits to the page since it was created in 2003. Things get nasty in the Great Edit War of 2009. “I don't know anything about David Sedaris, but it seems odd that [user] 96.233.125.251 would delete a well-cited reference. I suspect the user has an axe to grind with that source,” someone butts in. User 96.233.125.251 retorts, “There is no ‘axe to grind.’ This is more accurate. Leave it alone.” Another editor complains about being “wrongly blocked” from editing the page, and someone else concludes, “This is it's [sic] what accurate. Stop changing it to nonsense.”

What emerges from the edits is a kind of erasure portrait of Sedaris, a biography constructed from deletions and errors. It doesn’t capture the way he can condense a perfect agonizing moment down to its most honest core in just a few sentences. It doesn’t explain how he can whiplash readers between laughter and tears and make it look easy. But it does demonstrate the passion his fans feel for him, their willingness to fight for hours in a weird internet forum about every tiny detail of his life. Ladies and gentlemen, it’s my pleasure to introduce the man behind the Wikipedia page, David Sedaris.

In a world of betrayal and dark magic

Sponsors like Allan Batchelder make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? We've just opened up our new slots for spring and summer 2018. If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, reserve your dates now.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from November 20th - November 26th

Monday, November 20th: Columbia/Hillman Community Check-In

As part of their ongoing Inside/Out program, Town Hall asks the Columbia/Hillman City communities what they can be doing to assist inclusivity and togetherness in their events. This is worth attending even if you’re unfamiliar with Town Hall. This part of town has been changing for years, and it needs to reassess its cultural needs and desires before it moves into the future. Rainier Arts Center, 3515 S Alaska St, http://townhallseattle.org, 7 pm, free.

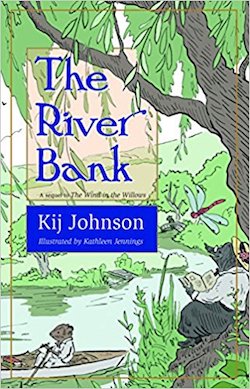

Tuesday, November 21st: The River Bank Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Wednesday, November 22nd: Duterte’s War Reading

Vincente Rafael, a UW professor specializing in history and Southeast Asia studies, will read from his latest book, Duterte’s War: Discussing the Current Crisis in the Philippines and Beyond. Tonight, he’s joined by Cindy Domingo and Velma Veloria in a wide-ranging discussion about the Philippines and the repercussions America might face if we continue to ignore the country. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, November 23rd: It’s Thanksgiving!

For god’s sake, go and eat a whole something or other, okay? And remember to be thankful. I know it's hard this year, but there are still some things that deserve your gratitude.

Friday, November 24th: Shabazz Palaces with Special Guest Gillian Gaar

Seattle hip-hop geniuses Shabazz Palaces are branching out and becoming multimedia moguls. Tonight, they debut their first-ever comic book, Quazarz vs. The Jealous Machines, with a signing and DJ set in Georgetown's fabulous Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery. Expect some neat things to happen when comics and hip-hop combine. Along for the ride is Seattle-area music writer Gillian Gaar, who will be signing her new book Hendrix: The Illustrated Story. Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore, 6 pm, free.Saturday, November 25th: Gobble Up!

Urban Craft Uprising — which happens in Seattle on December 2nd and 3rd this year — is warming up at Bellevue’s Meydenbauer Center this year with a food-themed event called Gobble Up! It features “some of the best artisanal and craft food makers in the Pacific Northwest,” including a number of local cookbook authors writing about food that can only be found in the Northwest. Meydenbauer Center, 11100 NE 6th St, 10 am, free.Sponsorships open through July, with a discount for past sponsors

You know who we think are the best people in the world? A hint: it starts with s and ends with ponsors. We owe a huge enthusiastic thank you to the more than sixty sponsors who've signed up to support us since we launched. By putting their projects in front of our readers, it means that we can pay writers, which is pretty dope. Also, unlike some advertising, our sponsors are pretty amazing and interesting — you actually want to read what their offering. They won't follow you around the internet like an annoying little sibling who you can't get away from. They won't profile you and sell it to another company. It's just a simple offering for you to read and look at. And they're popular! We've sold out every quarter we've put up for sale, sometimes nearly before they go public. How amazing is that?

That's why we're so thrilled to announce that we've just opened up sponsor slots through July 2018. If you're one of the people who have been emailing us about dates — here they are! If you've considered sponsoring before, step lively to pick up a prime week now.

And if you're a previous sponsor — well, we love you and want to show it. So, you get $25 off any slot through the end of today, Monday November 20th. Just or send a quick note. We're always happy to hear from you

Each one-week sponsorship includes an ad on every page of the site; a full page dedicated to highlighting your book, event, class, or workshop (got something else in mind? email us), and a thank-you on the home page and over social media.

Two years ago we wrote about how we're aiming to improve the model for internet advertising. Together, we can make an impact and change the conversation. Local publishers, venues, and writers across all genres — our sponsors are truly the best. They help us keep the site alive, and make sure we can continue to publish reviews by writers new and known. In return, sponsors get exposure to the most passionate reading audience we’ve ever seen. Find out more, and then reserve a slot before they’re gone.

Seattle's first Civic Poet is now Washington State's newest Poet Laureate

Humanities Washington announced the news today:

Humanities Washington and the Washington State Arts Commission (ArtsWA) are excited to announce that Claudia Castro Luna, a prominent Seattle poet and teacher, has been appointed the fifth Washington State Poet Laureate by Governor Jay Inslee.

Castro Luna takes over from current state Poet Laureate Tod Marshall on March 1st of next year. Marshall has been a tireless advocate for poetry in Washington state, but if anyone can keep up with Marshall's pace, it's Castro Luna. Humanities Washington points out the importance of her tenure:

As the first immigrant and woman of color to assume the role, Castro Luna will be advocating for poetry during a particularly fraught period for both the humanities (the current administration proposed eliminating the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities early this year) and immigrant populations, who are confronting uncertainty in the face of travel bans and heated rhetoric.

In her recent role as Seattle's first Civic Poet, Castro Luna created the Seattle Poetic Grid, a map of Seattle told in poetry. I can't wait to see what she does for Washington state during her two-year tenure as Poet Laureate.

Literary Event of the Week: The River Bank at Elliott Bay Book Company

Say you’re friends with a writer. Say one day your writer friend asks you to lunch. You ask what’s going on. She tells you, “I’m working on a book.” A book, you reply, that’s great! What’s it about?

“Well, here’s the thing,” she says. “I’m writing a sequel to The Wind in the Willows.”

Here’s where you’d gently try to convince your friend that she’s making a horrendous mistake, that the world doesn’t need a sequel to Kenneth Grahame’s beloved children’s classic. And just about any time, you’d be doing your writer friend a favor. But if your friend is Kij Johnson, you should just nod, tell her you look forward to reading it, and enjoy the rest of your lunch.

Johnson is one of the most important sci-fi writers in America today — one of the few names mentioned as a natural successor to Ursula K. Le Guin and a true standard-bearer of fantasy fiction. Her latest book, The River Bank expands on and explores the themes of Grahame’s novel with all the dignity and resourcefulness that the subject matter demands. (Johnson reads from The River Bank this Tuesday at Elliott Bay Book Company.)

As you’d expect from Johnson, River provides a feminist spin on Willows. The opening line identifies the most important change Johnson makes to Grahame’s mythos:

The news was everywhere on the River Bank and had been heard as far as the Wild Wood: Sunflower Cottage just above the weir had been taken by two female animals, and it was being set up for quite an extended stay.

It’s a divisive move:

The satisfaction felt by the feminine residents of the River Bank was not, alas, universal. A few days after the arrival of Beryl and the Rabbit, the Mole said to his friend, the Water Rat, “I do not see what all this fuss is about. We were going along very well without these two setting everything at sixes and sevens.”

Even the Rat, a confirmed bachelor, felt this was unjust. “Now, Mole, that’s not fair; you know it’s not. There was a lot of here-ing and there-ing at first, but now things are nearly as they were The young ladies keep to themselves. Why, we hardly see them!”

It’s like Twitter, with talking animals.

Fans of Willows will find much to appreciate here. Johnson appreciates the traditions — she writes a great, rampaging Toad — even as she builds on them. The animals of the River Bank, Weasel and Rabbit and Rat, all wrestle with big questions of change and tradition, and community. There’s a ransom plot, and a decent coshing. It’s all in good fun.

Johnson makes a bold inquiry into Willows’s class distinctions — it’s a story of upper-class men in a pristine rural land — and in so doing matures and expands the characters. She’s not burning down Grahame’s world, she’s engaging it in a deep and meaningful conversation, taking the characters by the hand and slowly introducing them to the modern day.

But even as she interacts with the world of Willows, Johnson never forgets to pay homage to Grahame’s gorgeous prose style — that deceptively lyrical language that lures children in and then grows and deepens with them as they age. Johnson is not intruding on alien land, here — she’s doing Grahame a boon by building on what came before.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for November 19, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Guardian editor-in-chief Katharine Viner published an open letter this week about the paper’s history and commitment to holding power’s feet to the fire. It’s a stirring account of the tough choices a newspaper makes — the risks that journalists face, to their livelihoods and persons, when they oppose the dominant political and social thinking. Under the implied heading now more than ever, Viner says, “We believe in the value of the public sphere; that there is such a thing as the public interest, and the common good; that we are all of equal worth; that the world should be free and fair.”

Here are two picks that show a gritty and determined commitment to the same ideals from regional papers here in the United States. Unquestionably there are many more each week that don’t make it past their local circuit but are heard by those who need to hear them. So don't be jaded, by the echo chamber or the flood of "content" crawling across the internet. In a time (now more than ever) when journalism is at the bleeding edge of financial survival, these writers continue to put their livelihoods on the line.

Walking While Black

Topher Sanders and Kate Rabinowitz at ProPublica teamed up with Benjamin Conarck of the Florida Times-Union on this story about racial inequities in ticketing for pedestrian violations in Jacksonville, Florida. Fines are small, but being handcuffed (a 13-year-old girl) or on the wrong end of a Taser for jaywalking is not, to say the least. It’s impossible not to feel furious or nauseated or both while reading this piece, especially these on-the-record comments by the local law enforcement.

In interviews, the sheriff’s department’s second-in-command, Patrick Ivey, said any racial discrepancies could only be explained by the fact that blacks were simply violating the statutes more often than others in Jacksonville.

“Were the citations given in error?” Ivey asked. “I have nothing to suggest that. Were they given unjustified? I have nothing to suggest that.”

In response to the ProPublica/Times-Union findings, Sheriff Mike Williams said, “Let me tell you this: There is not an active effort to be in black neighborhoods writing pedestrian tickets.”

Ivey said stopping people for pedestrian violations as a means for establishing probable cause to search them was also fully justified. “Shame on him that gives me a legal reason to stop him,” Ivey said.

'One of the most secretive, dark states': What is Kansas trying to hide?

At the Kansas City Star, Laura Bauer, Judy Thomas, and Max Londberg sweep aside the veil that’s dropped between Kansas State government and Kansas State residents: a child welfare system that’s geared to protect itself over the children under its trust; police operating without public accountability; the authors of key legislation (abortion, gun violence) protected by anonymity. Any one of these threads could have been a great investigative piece; woven together, an insane picture emerges: government by those in power, for those in power. Finally, something both political parties can agree on.

Both Democrats and Republicans have run opaque administrations, said Burdett Loomis, who worked for former Democratic Gov. Kathleen Sebelius.

“Once you’ve got that lack of transparency, unless there’s something that rocks the boat, the people who benefit from it are perfectly happy to let it be,” said Loomis, a political science professor at the University of Kansas. “Corporations, lobbyists, lawmakers, a lot of these people have no reason to change anything very much.”

The culture that stifles transparency has become ingrained, said Benet Magnuson, executive director of Kansas Appleseed, a nonprofit justice center serving vulnerable and excluded Kansans.

“There’s something about once that culture sets in,” Magnuson said. “It’s really difficult to move out of.”

I Was Already Leaving Florida When I Arrived

Changing tone, but staying on location: In a personal essay that’s both lyrical and muscular (characteristically, and appropriately for a swimmer), Lidia Yuknavitch talks about catching and gutting fish, and how to finally throw the hook of your childhood.

I think it might be true that arriving in Florida was a leaving. I was already leaving the moment I got there; I hated it passionately. Those scant years, between high school and college, everything in me was about leaving. I left my father’s house forever. I left my alcoholic mother. I left the boy I loved. I left the girl I was, the girl who did not know a god damn thing, in our garage next to my father’s Camaro. I left ever being abused again — except that isn’t true, is it — I found other fists later in life, I found other ways to punish myself when no one else was around to do it. And, the truth is, I left a bloodline near a sinkhole near my house in Florida.

The Afterlife of a Memoir

After 26 years of silence, Aminatta Forna published the story of her father’s hanging at the hands of the government of Sierra Leone. Beyond the usual intimate disclosures that memoir requires, she dealt with life-and-death questions of security: her own, her family’s, and that of the man whose purchased testimony led to her father’s death. A dramatic story and also a thoughtful piece about what conversations the author of a memoir starts with her or his readers, intentionally or not.

The writer of a memoir must necessarily reveal a great deal about herself or himself, and often about other people, too. You sacrifice your own privacy, and you sacrifice the privacy of others to whom you may have given no choice. They may enjoy the attention or be enraged by it. “People either claim it or they sue you,” the head of press at my publisher told me in the weeks before my memoir was published. I knew who might sue or come after me — members of the regime that had killed my father.

The Myth of the Male Bumbler

Lili Loofbourow betrays men’s best-kept secret: they are actually well able to recognize right and wrong. So how did we come to think otherwise?

Allow me to make a controversial proposition: Men are every bit as sneaky and calculating and venomous as women are widely suspected to be. And the bumbler — the very figure that shelters them from this ugly truth — is the best and hardest proof.

Seattle Writing Prompts: That ferry ride back into Seattle at night

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

It's worth going to Bainbridge or Bremerton just for the ride back some nights. If you do it enough, suddenly the ferry ride transforms. The first time you ride? It's a magical experience. The thrum of the massive diesel engines underfoot, the boat shuddering as those giant props push all that weight. The people sitting at their tables, playing cards, just hanging out. The cafeteria, and, I remember so acutely when I was a kid and would go to Orcas Island, the video games.

But ride the ferry too much and it becomes a huge bus. The people playing cards are bored, they do it all the time. Or, if not bored, maybe partway in the transformation that riding the boat allows us, this window into a world between worlds as we cross a barrier from one land to another.

The ferry is a thin place, a place between places. The bored people are in suspended animation, while the vibrant newcomers are awake with the excitement of the new — snapping pictures, staying on the cold deck with the wind whipping them, talking loudly and having a full-life moment. So the ferry contains two types of people, at least, and the shear between them can feel odd, like walking into a wax museum where half the figures are animatronic animals.

Sometimes, on rare nights, the energy is so charged there are riots.

No ferry ride is as special as coming into downtown Seattle at night. How many people get to see that view? How man crowd the waterlogged front windows so they can see? How many run out to try to capture it, how many professional photographers with their tripods setup are there to capture the skyline as only the ferry view would let them?

Watching the city approach, first on the horizon, then growing until it gets bigger than it should, it feels amplified in front of you, like a camera trick where you're point of view is shrinking as the buildings get so tall they appear to bend over you.

It just overwhelms your senses with the lights of the city, the approaching promise of...what? Home? A night out? Whatever it is, the reverse engines kick in, and the water roils in front of the ship. You push backward to slow down, and ease into the dock. Welcome to Seattle.

Today's prompts

It happened like this: as soon as the boat pulled out from the dock she went up to get a cup of coffee. It was against the rules to leave the truck, but she double checked all the cages and they were fine, and she was only going to be gone a few minutes. Less than ten minutes later she came down the metal stairs, opened the heavy door, and walked onto the car deck. The first sign something was amiss was the monkey sitting on top of the truck. The monkey holding the master cage key, and then, she noticed, just how many animals were sitting on all the cars surrounding the truck.

It was returning from Bainbridge that he picked his moment. He had a friend hiding with a telephoto lens on the opposite balcony. He brought her out, and kissed her, then got down on one knee. "Clarice," he said, "you've made my life so complete. I love you so much. Would you do..." — "you have got to be kidding me," came a voice next to him. A guy, thirties, burly. He stipped off his shirt and threw it over board, then ran to the railing, looked at Clarice, and shouted "I'm the king of the world!"

The worst shift on the ferry was working the ritual sacrifices. But if you didn't give leviathan his due there was no way to cross Elliott Bay without being dragged down into the brine by a tentacle the size of the Space Needle. So the new people always had to be the ones to do it. Toss the animals overboard alive, but bathed in the blood of fish — it was like a doorbell to the monster. But, it wasn't that part that was horrible, although the gruesome cruelty certainly would be. But no, it was when that first tentacle broke the surface, and you suddenly realized what lived under the ocean. You never felt safe passing over it again. You may have known in your mind that you were unsafe in the world, but until you saw the monster that controlled us all, it never really became true.

He was just in a pissy mood. His parents were being super annoying, and, like, riding him about everything. He wasn't doing well in school. He broke the television. He made his little sister cry. It wasn't his fault! They never even listened to what he was saying. And now, they were making him go to Seattle to stay with his grandma while they went on some lame vacation without him. "A second honeymoon" they said. So, he got the hell out of the car and went up on the deck. Screw them. He stomped through the cabin, and slouched down in one of the long banquet seats. Then he saw her — his fifth grade teacher. She was sitting with a man, and it wasn't her husband, and they were kissing!

They were waiting in the van until the ferry got away from the dock. Eight of them, armed to the teeth. In black clothes. They pulled balaclavas over their face. They had one mission: to break into the cockpit and take control of the vessel before it landed in Seattle. They had thirty minutes until they docked. It was time to move.

The Help Desk: I want to write a historical novel, but history is really, really racist

Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna Madrid can help. Send your Help Desk Questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I’m a white writer, and I’m writing a historical novel. One of the characters — a villain, I guess you’d say — is racist as fuck. This is important to the plot.

But every time I write his dialogue, I cringe. He says the n-word a lot. A lot. It’s historically appropriate for him to do this, and I try to incorporate other racist synonyms when I can, but the truth is that if this guy was alive then, he’d be saying the n-word a lot. A lot.

Cienna, I’m half-inclined to use asterisks for the word in the body of the novel whenever he says the n-word because I’m so uncomfortable using it, but I think that would be silly and pull the reader out of the story and I don’t think my publisher would allow it. On the other hand, I’ve noticed that Quentin Tarantino’s movies are aging about as well as The Jazz Singer in part because of his rampant use of the n-word. So what should I do?

Sondra, Northgate

Dear Sondra,

If you publish your manuscript, I can guarantee that no critic or reader will think, "not enough 'N' words for my taste." Part of writing well is understanding the power of language – when powerful words underscore your point and when they disrupt your narrative.

The N word is the most hate-filled word in the American English language. Period. An asterisk does not make it okay to use – if anything, it is an acknowledgement that you shouldn't be using it.

Yes, the word has been used historically in texts and no, I do not believe it should be censored from works like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but there is a difference between writing in a period and writing about a period. Your writing is informed by almost 150 years of brutal history after the works of Mark Twain.

As a writer, you know good writing involves showing over telling. There are plenty of ways to show racism and racist thought that are more powerful than going Nuclear – if you're stumped, look to our current president and his administration for examples. Or grab one of the synonyms you've been using and stick to it – repetition builds meaning, and by layering the racist actions of your character with his repetition of a less hateful word, your readers will have no problem understanding his nature.

Kisses,

Cienna

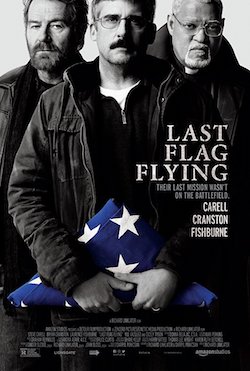

Last Flag Flying is a stellar film based on a novel by a Bainbridge Island author

If you haven't seen the 1973 Hal Ashby film The Last Detail, I'd urge you to do so. Detail, starring Jack Nicholson, Otis Young, and Randy Quaid as young Navy men on a road trip before one of them is put in the brig for a long time, is one of the most quintessentially American films I think I've ever seen. It's an ambitious, dark, funny film that name-checks Billy Budd and questions our assumptions about freedom and duty.

Richard Linklater's new film Last Flag Flying is a spiritual sequel to Detail, but it's not a direct sequel. Both films are based on novels written by Bainbridge Island author Darryl Ponicsan (Ponicsan co-authored the screenplay for Flag with Linklater,) and both feature three military men on a road trip. But the men in Flag are Marines, not Navy; the names of the characters are different; and the timelines of the films don't quite line up evenly. Still, Flag picks up the spiritual threads of Detail and spins them out into a story that's a little wiser, a little slower, and a little bit more disillusioned than the 1973 film.

Steve Carell's Larry Shepherd is the Quaid character, the younger innocent who sets the plot in motion. Laurence Fishburne plays Richard Mueller, a former hellraiser who has turned to Jesus and now lives as a reverend. And Bryan Cranston absolutely slays as Sal Nealon, the rabble-rousing smartass who nevertheless misses the time he spent in the Marines. (One relatively unknown actor, J. Quinton Johnson, plays a supporting role as a young Marine assigned to the three older men; Johnson more than carries his weight with these great actors, here. I expect to see more great things from him in the very near future.)

Cranston is playing the Nicholson role here, and it's a knockout performance. He's a huge dick — an alcoholic asshole who loudly tells you how horrible he is and then immediately demonstrates that he was telling the truth all along — but there's something so lovable about his bombast that you can't ever quite turn your back on him. Cranston builds on Nicholson's performance in Detail by making his character a stand-in for American weariness. He notes that America doesn't build anything anymore. He has disparaging words for the Iraq War — the film is set in 2003 — and he laments a simpler time when men were men. His nostalgia is wrong-headed, but his sadness is real and raw and very relatable.

Flag is a very talky, slow-paced film. It doesn't have the cathartic youthful vigor of Detail. These are three older men who've been beaten down by life and duty and the death of their dreams, and anyone expecting a wild dance party that fixes everything is likely in the wrong theater. But if you have a taste for slow and talky films, you might not find a better one this year. The writing and pacing of Flag is exquisite, and the questions it raises about belief and friendship and honor are piercing.

And while Flag will inevitably be compared with Detail, there's another film in theaters right now that deserves mention, too. Greta Gerwig's directorial debut, Lady Bird, is also set (partially) in 2003, and Lady Bird and Flag would make for a stellar weekend double-feature. Both films wrestle with the American response to 9/11 and the beginning of the end of our imperial authority as a nation. Both films capture a moment before technology consumed every waking moment of our attention. And both films depict very different moments in the ongoing conversation between individual and society.

Nearly 15 years later, we're just starting to realize what it is we lost as a nation, and how we lost it. Small, funny, brilliant films like Lady Bird and Last Flag Flying are a big part of how we'll finally be able to understand what happened to us.