In a long and thoughtful post, Seattle Mystery Bookshop owner JB Dickey explains why he's closing his bookstore at the end of this month. I'm sad the bookshop couldn't find a new owner, but I'm glad that Seattle had so many wonderful years with such a wonderful bookstore.

When this cartoonist broke his right arm, he taught himself how to draw with his left

From his Punch to Kill comics to his work organizing the dearly departed Intruder magazine, Marc Palm is one of the most active members of Seattle’s cartooning community. So when Palm announced on Facebook earlier this summer that he broke his right arm — his dominant arm, the arm that did all his drawing — the community responded with a visceral heartbreak: one of Seattle’s most prolific and enthusiastic cartoonists was going to be out of commission for the foreseeable future. But then Palm did something unexpected: he taught himself how to draw with his left hand. I talked to him in late August about his experiences.

Thank you for doing this. I’ve been following along on your journey on Facebook and I think it's really fascinating. Let me start with a couple of personal anecdotes. I want to get your impression of them.

First, I had a friend who was an artist in high school. His mother likes to tell the story that when he was a kid he used to walk around the house with his hands in oven mitts. He'd hold his hands in the oven mitts right up to his chest because he was so terrified that anything would happen to his hands.

Oh, wow.

He identified as an artist so much that it was like a fear for him. He felt like he’d have no identity without his art.

And then second, my grandmother was born a lefty. At her school they tied her left hand behind her back until she became right-handed, because they thought left-handedness was a weakness of character.

Is she alive?

She died, a long-time ago. But she had Alzheimer's, and she actually reverted to left-handedness toward the end there. I thought those two stories might give you an idea of what I was thinking about when I heard about your story.

Speaking of which, I want to shut up and hear your story. So to start at the beginning, you bought a skateboard, right?

Well, no. For the last couple of years I've been getting more and more interested in skateboarding. When I was 12, my parents got me a skateboard — a big clunker. Then they got me pads and helmet and all this other stuff to be safe. And I tooled around in my driveway, which was the smoothest surface I had. But even then, I didn't wear gloves. I didn't wear oven mitts walking around or whatever, but I was a very careful child.

I've been a very careful person my whole life, really. So when I was 12 I was like, ‘You know. I think I'm gonna hurt myself. I don't really want to do this.’ Skateboarding was just cool to watch. I was gonna be a fanboy of it.

But then in the last couple years I was just getting more and more into watching it, and admiring it and thinking, ‘Wow, this is cool. Maybe I should give this a shot.’ So, [Seattle cartoonist] Ben Horak said, ‘I got this board I picked up from somebody. I'm never gonna use it cause I'm too scared to hurt myself, if you want it.’

He hands me off this skateboard. And whoever had it before, they actually were a skater. The thing was pretty well ground up, and it worked well. I was kind of tooling around wherever I could.

A couple of other cartoonists and started skating. They were very encouraging like, ‘You're not gonna hurt yourself. Don't worry about it.’ So we'd go find flat surfaces — tennis courts or parking lots or whatever. We call it ‘skate dad parks.’

That's where, inevitably, it happened.

It was the big Gotham Asylum up on Beacon Hill — the hospital up there. We found this great parking lot. No one bothered us. So I was off on one side, and they were on the other, and I just made this turn and there were some rocks, and I just stopped the board. And then I just landed directly down on my wrist, and that's when I eventually broke a chunk off the ... I forget what that is. It's one of the long arm bones.

I had never broken a bone, and I tried my best to avoid it. Until picking up a skateboard.

It was the worst fear that I had. [When I started skating,] other people were like, ‘What if you break your drawing arm ?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, I know, but it'll be fine.’ Then the worst case scenario happened.

Just to get some background: you're a fairly prolific artist. It seems like you must draw every day, right?

Yeah, I try to. It's definitely in my blood. And I've been doing it for thirty-plus years — just constantly producing and trying to do my best. But I'm not gonna kill myself over a broken arm. I just started going down the process of seeing if I could draw with my left.

My mom has a similar story to your grandmother’s. She was a lefty. She went to Catholic school, and they bound her left arm and forced her to go right. She eventually, grew out of it and went back to being a left-hander.

But while raising me she forced everything into my right hand. She was hoping that I wouldn't be a left-hander because she thinks it’s a curse. The world is right-handed, and she didn't want me to deal with the same problems she had. It's possible that I could have been a left-hander, had it just come naturally.

After you fell when did your thoughts turn to the fact that this was going to really screw up your drawing? How soon was it before you realized?

It wasn't like a big revelation, but it was definitely like, ‘Ugh, fuck. I broke my wrist. I can't draw.’ It was immediate and I tried not to be too bummed out about it. I was more annoyed that now I'm gonna be completely inconvenienced — I only have one hand. I work at the Fantagraphics warehouse and my job is lifting up packages and packing things and now I'm kind of wrecked on that.

I just thought I was gonna have to take a break. Which stinks, because I have a book that I'm working on, and hoping to have done by Short Run. I immediately just realized I had to try to figure something out.

What did that process look like?

Oddly enough, months ago — maybe even a year ago — I was having a little paranoid fantasy, wondering what would happen if I couldn't use my right arm — if it got cut off or I broke it. I was just fascinated with the idea of what my left arm can do that my right can't.

So I tried buttering my bread with my left, and I realized that these two hands had no idea what to do when they're faced with something the other hand usually does. My right hand didn't know how to hold the bread properly, and my left hand didn't know the subtleties of spreading with a certain amount of pressure without stabbing through the bread.

I played around with that. I'd started to be more efficient. I’d remind myself, ‘why don't I just grab the door handle with my left hand because that's where it's at instead of reaching all the way over from my right?’ I was already trying things with my left.’ I hadn't really tried to draw or anything, but I farted around and, like, tried to write my name with my left. It never went well.

So then, a couple days [after I broke my arm] I grabbed a big fat pencil, and I thought ‘maybe I can come up with a cute style,’ because normally my stuff's grotesque. I thought maybe I could actually draw cute things with my left hand.

So I was drawing dinosaurs just to start out. They did look kind of childish, and it was hard to have the control that I wanted. But I saw that I could do something, so I just needed to focus a little harder.

So I changed tools. I went to the smallest micron pen I have. It's a .005. I started going really small and I found that when I was doing details with my left hand, I had a lot of control. But if I made big gestures, or made big strokes, it would get all wiggly and I didn't have the kind of control I wanted.

Wow, that is the exact opposite of what I would figure would happen.

I had a bunch of people encouraging me to try drawing with my left hand. At first, it kind of annoyed me. I was like, ‘You know, this is kind of a cute, fun thing to post online, but it kind of hurts.’

So after I did those dinosaur drawings I put one up right away. I was like, ‘All right, here you go. Everyone that says I should draw with my left, here's the drawings. Fifty bucks, let's go. If you want to support me, put your money where your mouth is.’

Yeah.

‘Or keep your cute little comments to yourself.’ All right, yeah, I could draw with my left hand. So then I just started working on it. As far as being an artist, you're basically dealing with like problem solving: ‘I've got a picture in my head. I need to get it on paper. How do I do that?’

And what was fascinating to me about doing this, was my way of working doesn't come from my right hand. It’s not the hand that does it — it's my brain. I can visualize where things have to go. I've studied enough brush strokes and different techniques. I just needed to be able to get my left hand become a good tool, to get those lines to flow the way I want to.

So yeah, I took my time and really had to be patient and focus on the circle, where before, my right hand had been doing it for thirty close years. I was struggling to draw these little things. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is what it's like for like a normal person who doesn't know how to draw. I could see why they give up. This is hard!’

I realized that this is an enormous amount of work.

It basically was just working through it — figuring out how delicate I have to be, how hard do I want to press on this, what kind of style do I want?

Now I see it as really cool and fun. I'm kind of addicted to it.

Do you draw every day now with your left hand?

Yeah. I go to a coffee shop and sit there for an hour before work and just draw. And that was a great exercise. Every day, I sit there and pump out a new drawing.

And all the drawings I would be posting would take me two days or two mornings — an hour or less apiece. I even picked up speed as far as the amount of time I was working on them. I could do it faster and faster, and get more precise. It's interesting how it's an exponential growth of ability.

I feel my brain swelling.

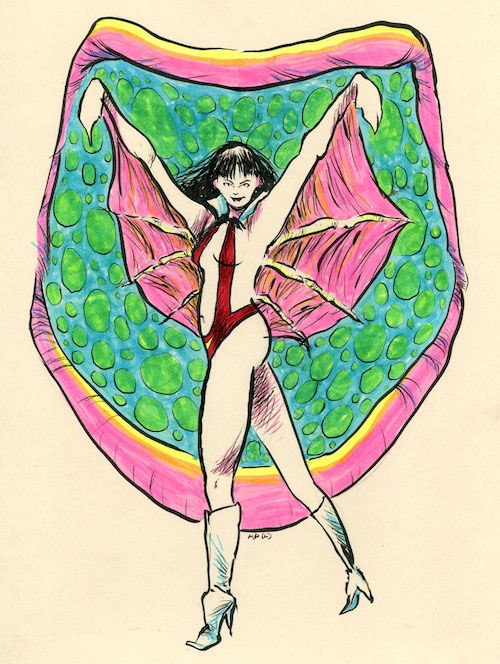

Yeah, you really got good. I was following your story on Facebook and it seems like all of a sudden, you put up that drawing of of Vampirella, and I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ I don’t know how hard you are on your own work, but even you have to acknowledge that the difference is pretty impressive.

Oh no, that's the thing. It's weird because people come up and say, ‘Wow dude, you're drawing really well.’ And I share in their amazement: ‘Yeah, I know, right? These are really fucking good.’ And it's weird. I don't want to seem like I'm egotistical but I'm surprising the hell out of myself with this.

With that Vampirella one, I was sitting at home and just kind of sketching. I drew a different type of line. I had actually been trying to get to a point like that — I guess, like a looser style. It’s been hard to teach myself to get looser when I've been trying to get tighter and tighter for years. And so my left hand had that looseness that I was looking for.

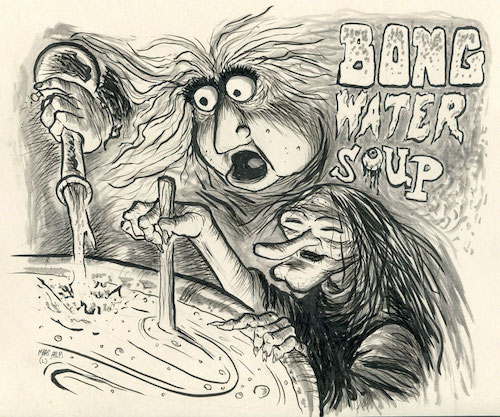

It's just been really weird and awesome to see it happen. The big drawing that blew my mind that I was able to complete it and make it look as good as what I would do with my right hand was the one with two witches brewing up the bongwater soup.

I use a brush pen usually, but I pulled out a nib pen I hadn't used in years and it worked out great. It was like this cool new toy to play with and get different effects.

There's still a difference between your left-hand and right-hand style, though, right? You've gotten better, but you haven't gotten the same.

No, but I'm definitely getting closer, which I'm not sure like.

It's kind of fascinating — I talked to one of my other cartoonist buddies, Kalen Knowles. He said, ‘What if I told you I like these [left-handed drawings] a little bit more than your other stuff?’ And my girlfriend was getting close to saying that to me too.

It's weird to me because I've been working so hard to get a style that I can be comfortable with, and can produce well with my right hand, for so long. And now I'm coming up with this little bit more naïve, or raw, look with my left, and everybody's like, ‘Oh, I like that better.

It also looks more hand drawn. I guess that's what he was saying; it looks like it has a little bit more of a human hand to it.

And I think some people are drawn to that because it looks like something that they'd be able to do. I've had a couple of people say they like stuff that looks not too polished. If it's so polished and super hyper-realistic, they can't even understand it.

But if it looks like someone drew it, and there's mistakes and there's a wiggly line, then people get that. There must be something identifiable about it.

I've been trying to be cautious or kind of aware of how clean and how good my stuff looks, because I don't want it to look like it's made by a computer. I don't like a lot of digital art a lot of times. I see it as soulless. It's too clean, it's too nice.

So if [art drawn with my left hand is] a little rougher, or hand-drawn, or there's a mistake, that's cool. But I don't want my art to be full of mistakes. I look at a piece of my art and I see all my mistakes — I don't see how good it is. And I think that's the hardest thing for artists — liking your style, liking your little quirks, and all the strange things about it. Hopefully, your tastes match up with your audience.

So the cast is off, right?

Yeah, it came off yesterday. Thank God.

Have you been drawing a little bit? Have you had time to readjust to the right hand?

No, I’ve still got to go through some physical therapy. I have a new splint.

But I'm going to have to [get back into drawing with the right hand] because I've got to finish the vampire book I'm working on. I'm interested to see if my right hand has to learn to catch up now. Will I be able to jump back in? Or will my left hand now become the superior hand?

I'm looking forward to using the left hand to sketch out things, or do my rough pencils, because it has that looseness. And then I'll ink it with my right hand so that I can get a tighter look.

So you’re looking to use both hands in the future? Like, at the same time?

I'm not a gecko. I can't spread my eyes and look at two different drawings at the same time. Not yet. I may well try.

Maybe you just need a head injury.

Be kicked in the head by a mule.

Do you think you're going to finish the vampire book by the time Short Run happens on November 4th? Are people going to be able to see your latest stuff at your booth at Short Run?

Oh yeah, for sure. I have only a few pages left on the vampire book. It’s called The Fang and it's about a female vampire who has a job as an assassin of monsters.

I'm also thinking about coming up with a left-handed publication of some sort. Like the closest thing I'm ever going to do to an autobio comic, with photos, probably collages, and some sort of skate art. A photo of my skateboard, and x-rays from my hand, and then all my left-handed art. I think that's something I should definitely do.

I want to see if I can get, at the very least, a coffee shop to host a bunch of left-handed drawings.

Do you have a book out right now that you think is a perfect example of your right-handedness at its apex, before the accident? So that readers can do a before and after comparison?

Oh yeah. The Punch to Kills are the best I've done. And then, The Fang book is definitely the thing that I've been really excited about doing all this year. It definitely is looser than the Punch to Kills, I think, and a little bit more fun.

So, yeah, there should definitely be stuff for sale at Short Run, so you can look at what I did this way and that way. Choose your poison. Pick your hand.

The Sunday Post for September 17, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Sorrow and the Shame of the Accidental Killer

A broken glass; a stumble on the sidewalk; a misplaced word that leads to hurt feelings. Most of us screw up on a daily basis, and for the most part we can fix it with a little glue and an earnest apology. What happens when you hit the top of the screw-up food chain, though, and someone dies? Alice Gregory explores the aftermath of accidental death and why we have so little to offer the survivors.

There are self-help books written for seemingly every aberration of human experience: for alcoholics and opiate abusers; for widows, rape victims, gambling addicts, and anorexics; for the parents of children with disabilities; for sufferers of acne and shopping compulsions; for cancer survivors, asexuals, and people who just aren’t that happy and don’t know why. But there are no self-help books for anyone who has accidentally killed another person.

The Google Bus

In the wake of Amazon’s announcement that they’re planning to grace another city with HQ2 — an announcement met with either consternation or celebration by Seattleites, depending on inclination — read this reflection by Google staffer Min Li Chan about the tech giant’s impact on San Francisco. Chan has been moving toward Google since she was nine; she’s living her childhood dream. But she’s also watching the job she loves steal the city she loves and lives in.

When the first bus protests erupted in late 2013, my peers and I reacted with bewilderment, certain that we had been unjustly cast as scapegoats for the city’s problems. “Why are they angry at us?” a friend remarked one night over dinner. “We haven’t done anything wrong, we’re just trying to get to work!” That morning, a man had driven by our tech shuttle stop in his beat-up Honda Accord and given all of us the middle finger while leaning on his horn. As my friend and I recounted other instances of aggression we had witnessed or heard about, other guests — close friends who didn’t work in the industry — listened. “But you guys get why this is happening, right?” asked one after we had finished our meal. After everyone had gone home, I turned her question over in my mind. In the calculus of culpability, I had believed that as well-meaning technologists and productive members of society, we were irreproachable. How could we be wrong?

Is It OK to Make Fun of Instagram Poets?

Lisa Marie Basile jumps into the Instagram poetry fray after Electric Literature’s recent evisceration of practitioner Collin Yost. This gets stickier the deeper you go; the Twitter exchange (between Portland writer/artist Izze Leslie and Yost) that sparked this particular flamewar went ad hominem quickly and across multiple social media platforms. Basile steers us onto higher ground with some good (oft-trod, but never too oft) questions about the value of verse.

On one hand, I personally don’t think it’s excusable to pump that sort of drivel onto the Internet — especially because of the fact that those Instagram poets, whose work is heavily tied to the Internet, likely have access to other poets’ work on that same Internet. By reading anything published in a literary journal or a release from a small press (which I think is partly a duty of being a poet) or even work by another poet that isn't published, they must have some semblance of knowledge around what constitutes original writing that doesn’t rely on gimmick or cliché.

But if these poets want to write what they write — and if their readers are getting some sort of emotional response out of it — is that not what matters?

The Battle for Blade Runner

With a Blade Runner sequel coming soon, Michael Schulman has a short history of the making of the original. It’s just as chaotic and fraught as you might imagine: Scripts are written on the sly, there’s a near-mutiny on the set, and Philip K. Dick goes creepily head over heels for Sean Young. Here’s just one anecdote, in which Ridley Scott delivers an unwelcome surprise to writer Hampton Fancher:

Then, around Christmas 1980, Scott’s aide Ivor Powell invited Fancher for dinner and handed him a script. Fancher figured it was a different movie entirely, until he flipped the page and realized it was a re-written Blade Runner. “I stood up and started crying, tears coming down my face,” Fancher recalls. “Ivor put his arm around me. He told me this was going to happen before — he said, ‘I know my man. If you don’t do what he wants, he’ll get someone who will.’”

Days later, Fancher stormed into the production office and screamed, “Why?!”

“Elegance is one thing, Hampton,” Deeley told him. “Making a film is another.”

“Fuck you guys,” Fancher said, and returned home to Carmel.

Drummer Jon Wurster Remembers Grant Hart: 'The Center of the Sonic Hurricane'

We don't ususally count our dead in the Sunday Post, even on a week of notable losses. Many are mourning Harry Dean Stanton this weekend, rightly; on the non-human side, we obsessively and collectively tracked Cassini's final flight in our imaginations, through the lens of history, and through images.

But if you grew up in a certain midwestern city, there was one death this week that stung even more sharply: Grant Hart, the better half of Minneapolis punk band Hüsker Dü. Many will take issue with "better half," but Grant would love it. And it's sweet, smartass Grant Hart who always belonged to his hometown — no matter how far he traveled.

I first laid eyes on Grant in December of 1983. Hüsker Dü were sharing a bill with SST Records labelmates the Minutemen at Love Hall, a rundown punk dive on South Broad Street in Philadelphia. Grant was being shown around the freezing venue by the promoter before the show and I remember thinking how "un-punk" he looked in his trench coat, paisley shirt and long hair. He looked like a hippie who was on his way to see Hot Tuna but walked into the wrong club.

Any doubts I harbored were obliterated when Hüsker Dü launched into "Something I Learned Today," the lead-off track from their upcoming double album Zen Arcade. I can only liken seeing Hüsker Dü that night to the daze of disorientation you feel after accidentally banging your head on something very hard. It was punk, it was pop, it was jazz, it was psychedelic; it was an ear-splitting swirl of sound. And at the center of the sonic hurricane was Grant Hart, arms flailing, feet flying, laying waste to every drum and cymbal in his path.

Seattle Writing Prompts: shipping containers

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

You've seen them stacked like mini-skyscrapers driving 99 through SODO. On the Duwamish side, the towering animal-like cranes, whose job it is to move them from one method of conveyance to another. On the other, those hunched-back rail cranes, that pick up and move them in the yards.

Containers hold our imagination in specific ways. We want to buy them to turn them into houses, shops, studios, boats, and even, of course, Starbucks.

There's just something about those corrugated metal boxes that makes us want to repurpose them into something else. Their first job, though, is to move goods. In fact, what you think of when you hear the name "shipping container" is actually called intermodal containers. They come in standardized sizes, but the real breakthrough in their technology came when a Spokanite named Keith Tantlinger who made some important improvements on existing containers (mostly standardization), but invented the twist-lock that today's containers use so that they can stack. It changed shipping forever.

If you read Jonathan Raban's magnificent novel Waxwings — which starts on the bridge of a container ship about to enter the Salish Sea as a pilot boards to guide the ship to harbor in Seattle — you'll know that containers play a part. Containers are story machines, each one full of things we love to think about, dream about, or need to do our work. And when humans make things and need things, no doubt there are going to be many stories around those things just waiting to be explored.

Today's prompts

Sometimes the twist-locks seize. Salt air, corrosion, etc. Sometimes you have to get in there and cut the damn things free. But he checked all four corners and they were in the release position. So why couldn't the crane get the container free of the stack? Making sure he was well clear, he radioed for the crane operator to try again, and like before, the container stuck tight to the one under it, like it was super-glued in place. It was weird. And then, a surging hum and the wrench he was holding went flying and stuck to the side of container. Magnets? There weren't any magnets that powerful on the earth. He radioed to pull the crane free. "I'm gonna crack it and see what's inside."

They didn't have the nerve to say it to her face. But her neighbors — at least one of them, and maybe more — sent an anonymous note to her email, threatening her with a lawsuit if she continued with the plans for her new house. "Your plan to build using steel boxes is incongruous with the careful design of our neighborhood," the note read. "Should you persist, there will be lawsuits." She wondered if it was the person who lived in the Tudor, or the craftsmen, or the mid-century rambler, or the eighties knock-off architect's nightmare house? Which congruity of those would she be impacting by building on her own land?

The planning had taken twelve Earth years. Where was the least likely place for Earth radar to pick up their craft landing? They decided in the middle of the Atlantic ocean, and to mask their decent through the atmosphere to be like a meteorite falling. The mothership could go to the bottom of the sea, then, by the time any jets were scrambled to check them out. And then, they would launch their container ship, and it would go right into port, without anybody knowing. The perfect Trojan horse, and nobody could stop them before they were fully distributed throughout the cities, and it was too late.

The sealed container auctions were his favorite. Something about a gambler's sensibility that knew the promise of something was better than the reality of bored nothingness. So, a few thousand dollars and he'd have a container full of goods. Of what? Of shoes, or sawhorses, of cheap-ass electronics or knock-off Stetson hats, electrical panels for houses, or elevator cables, plastic bottles, climbing gear, or who knows what else? But when he opened his latest lot, he found something far more unsettling: a house-worth of furniture and goods. It was a family's life he just bought, and all he could think about was how much they needed their stuff. How much the move — from where? Hong Kong? — had cost them, and he wondered if he could figure out just how to find them.

They wash up on the beaches, sometimes, still. Daddy says it was the great wave that done it, but I know it was the pulse from the sun that killed all of the electronics. Daddy says they used to talk on little boxes, used to use glowing screens to see faces of people far away. One time, he opened the big box on the beach and showed me, with happiness, "This is a laptop, Dumpling. I wish I could turn it on and show you how it worked." We took all the boxes of them, hundreds, and stacked them in my room. I use them like blocks to make other rooms, but I've opened a few. I like to poke at their buttons and see. Sometimes I shoot them with the shotgun to watch them explode, but Daddy doesn't like when I do that because of contamination, whatever that is. So when I saw a new red box come up on shore I had to go get him, and we waded out to it to see what could be inside. Every time it was the thrill of the new. Every time was like a present come to us. Both of us acted like little kids as we walked into the water to see what we were gonna get.

The transmogrification of Kesha Rose Sebert

Published September 15, 2017, at 11:48am

Kesha's latest album, Rainbow, can be read like a memoir. But is it a story of triumph, or is it a more complex story than that?

The Help Desk: This floor, boys. Next floor, mens.

Cienna Madrid's Summer cold has decided to stick around past the dog days. She's sick so we're rerunning this column from October of 2015. Our intrepid advice columnist will be back next week. And please remember to keep sending your questions! Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Ask her at advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

There's this guy who rides the elevator with me at work pretty often. He always has a big, complex book in his hands — Bolaño, or DFW, or Knausgaard. He's pretty good looking, but I've held off smiling at him because I'm worried his choice of books means he's going to be pretty intellectually limited. Is there a safe way to test him in public before asking him out on a date?

Pat in the Columbia Tower

Dear Pat,

Here’s what I suggest: Start carrying around a copy of your favorite book in your bag. The next time you’re stuck in an elevator with this handsome stranger, break the ice by saying something like, “I notice you read a lot of very serious books written by unsmiling men, so I thought you might enjoy this change of pace. It’s my favorite.” The beauty is, it doesn’t really matter what your book is – it could be something truly great, like Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild, it could be last week’s TV Guide, or it could something he might actually enjoy, like the latest bullshit pumped out by Jonathan Franzen (if you go the TV Guide route, it helps to tape an unused condom to the inside cover). The point is, you’re being both flattering and assertive. If he’s smart and interested, he’ll read your book or at least continue the conversation. If he’s an intellectually stunted dummy, say “fuck it” and ask to see his abs. They can’t be any less interesting to talk to (and if by some miracle they are, you can always start taking the stairs).

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Jamie Ford

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Saturday, September 16th: Love and Other Consolation Prizes Reading

Jamie Ford, the Seattle author who previously wrote a celebrated novel about the International District, returns with a novel about Seattle’s 1909 World’s Fair. It’s the story of a boy who is raffled off to a supposedly “good home” that turns out to be a brothel.

Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com. Free. All ages. 4 p.m.

Future Alternative Past: covering it

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Judging a book

A cover’s the first thing you see when you look at a book. Maybe the spine alone — a wash of color, font(s) spelling out its title and the name of its author (with any luck, legibly). You see more if the book is “faced out,” that is, displayed so the front cover’s facing you, and you’re getting the full force of the artist’s and designer’s skill. What can you tell at first glance?

For starters, expensive treatments such as embossing, cut-outs, and foil or metallic inks mean the publisher thinks they’ll be selling lots of copies. Traditionally, the publisher’s got an in-house team taking care of the cover business; traditionally, authors have little to say about how their books are packaged beyond, if the publisher’s feeling extremely gracious, a chance to nix the chosen art. Which Tor gave me with Everfair; editor Liz Gorinsky showed me a preliminary sketch done by the brilliant Victo Ngai and I pointed out that the human hand in it should be black. And she made it so.

But protagonists’ races aren’t always something you can tell from a cover, alas. “Whitewashing” is the term we use for this problem. For every piece of representative and lushly dark Kai Ashante Wilson or Nnedi Okorafor cover art, there’s a counterexample, such as the weirdly pale version of Lilith Iyapo shown on the original edition of Octavia E Butler’s Dawn. Of course that last book was published thirty years ago; nowadays, a mostly abstract or alphabetic cover like the one on Zen Cho’s wonderful Sorcerer to the Crown is the compromise.

Not that there’s anything intrinsically wrong with alphabetic cover designs — one of my favorites is the cover for Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, reproduced here on a t-shirt. But I contend it’s shabby of publishers to routinely use graphics to conceal information they think you shouldn’t have.

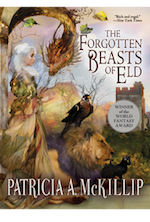

Because there are times they do exactly the opposite for the information they think you should. Goggles, top hats, and dirigibles on a cover signify steampunk; spacesuits and cratered, airless planetscapes signify “hard” science fiction; busty contortionists in jeans or leather catsuits signify “urban fantasies” about werewolves and private eyes. Delving deeper into this code, specific artists are identified with specific subgenres and even with particular authors: Thomas Canty with high fantasy, Kinuko Y. Craft with Patricia McKillip (I review a classic McKillip re-issue later in this column).

Publishers speak cover art fluently. If they want to.

Another thing you can usually tell from a book’s cover: who else thinks it’s cool. Traditionally, publishers are also in charge of soliciting “blurbs,” as the two-or-three sentences of praise bestowed by big names are called. The results can be edifying. If the book jacket prints a statement from Samuel R. Delany or Junot Diaz saying a debut novel is brilliant, I pay attention; if it’s lauded as amazing by someone who…isn’t…I pass it by.

So yes, often you can judge a book by its cover. But then there are those times when things go horribly wrong. The cover art for the first printing of Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others has a clumsy Ayn Rand-paperback feel entirely at odds with the collection’s ambiguity and subtlety. “There’s a Bimbo on the Cover of My Book” laments a familiar filk song (folk songs for members of the SFFH community). “All too accurate,” one commenter proclaims of the song’s full lyrics.

One way around these messes is to self publish. Another is to publish with a small press such as Tachyon, Aqueduct, or Small Beer. In both cases authors are better able to plead their book’s cases to the judge and jury of the reading audience.

Couple of upcoming cons

There’s a first time for everything, including AfroComicCon, a Bay Area “comic book, art, media, science fiction, technology awareness, web TV, film, and writing convention.” You get all that for a ticket costing $7 to $30 — depending on which events you opt for. A free-of-charge Youth Community Day is promised also, though no details are available yet. Jaymee Goh and Zahrah Farmer Castillo are two of this fledgling con’s fourteen featured speakers.

VCON, on the other hand, has existed since 1971. This year’s VCON 41.5 is billed as a “relaxacon”: light on programming, heavy on socializing. It’s a format that will likely work both for longtime attendees who just want to hang out with old friends and newcomers who’d like to get a feeling for the con community. Structured only around the length of a movie or the rules of a game, VCON 41.5 could be a revealacon as well.

Recent books recently read

As noted above, recent covers for Patricia McKillip’s fantasies are almost always painted by Kinuko Y Craft. Except when they’re not; a new reprint of her groundbreaking World Fantasy Award-winner The Forgotten Beasts of Eld (Tachyon) is graced instead by Thomas Canty’s art. And why not? McKillip’s soaring prose, lyrics to songs our hearts have forgotten they knew how to sing, deserves Canty’s accompaniment. The feminist underpinnings of the book’s plot — a self-sufficient woman who refuses to be stripped of her autonomy starts a war she swore never to fight — deserve our attention now as much as they did in 1974, when Beasts was first published. If you’ve never read it, you deserve to. Or if, like me, you read it long ago and have made do since with a tiny but affordable mass market paperback, you deserve Tachyon’s elegant trade paperback edition, at least half as beautiful as McKillip’s story. Which sounds stingy as compliments go, but is actually extremely high praise.

Frankenstein Dreams (Bloomsbury USA), a retrospective edited by Michael Sims, is fourth in his series of Victorian SFFH anthologies. The book begins with a detailed introduction, then proceeds to work by Mary Shelley, author of what’s arguably the first modern science fiction novel, and ends with Arthur Conan Doyle, whose iconic sleuth Holmes epitomized the scientific approach to mystery. In between these two Sims manages to introduce several authors less familiar to modern SFFH readers, or probably to modern readers of any genre. He also takes the somewhat regrettable liberty of excerpting a minor and wholly non-sfnal Thomas Hardy novel, justifying it as an illustration of the anxiety the time’s scientific discoveries provoked. Other excerpts — of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, of Shelley’s superb Frankenstein, of Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, and of Stevenson’s Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde — may tempt the antho’s audience to read the complete novels they’re taken from. They stand up poorly to the real short stories appearing here, though, such as Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar” or my favorite, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s “The Hall Bedroom.” Gender issues are addressed in “A Wife Manufactured to Order” by Alice W. Fuller, and racial prejudice in Edward Page Mitchell’s “The Senator’s Daughter,” but for the most part Frankenstein’s Dreams seem to center on explicit monsters and the implicit estrangement of members of the era’s dominant paradigm.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Blue collar special

On Labor Day, I argued that we need more blue-collar novelists. The thing that I didn't note in that essay is that there are plenty of contemporary blue-collar cartoonists — not because the comics industry is so forward-thinking but because the comics industry does such a poor job of compensating artists for their work. Unless they're a superstar name or someone who works on a number of different gigs simultaneously, the odds are good that your favorite cartoonist is either A) indepdendently wealthy or B) working multiple angles to make ends meet.

Madge feels pretty grown up when she scores a job at the Imperial. She's living with roommates, she gets a boyfriend, and she falls for the eccentrics who frequent the Imperial — on both sides of the counter. But soon enough, people start ODing on heroin, or doing too much coke and getting violent, or having brushes with the law. It's a coming-of-age story set in the school of hard knocks.

Tying together all of the anecdotes that make up Wrong is the work: waiting tables is the baseline of the book. Madge walks around with a carafe of coffee in one hand, chatting with customers, learning what she can about the world from the booths of the Imperial. Sometimes the kitchen is slammed and Madge has to try to charm her tickets to the top of the to-do pile. Other times it's slow and she shoots the shit with regulars. It's a book that's intrinsically tied to the dignity — and indignity — of work.

At nearly 450 pages, Wrong is a mammoth-sized comic. You'll have to take your time with it, and that's how it should be. It's a memoir that takes you through the days and nights of its main character, and it slowly transforms Madge in such a way that the reader barely notices until the transformation is complete.

Pond's art is perfect for this kind of serialized novel of a story: her art is cartoony but finely detailed. Madge's face is just a couple of lines, but Pond draws every stave in the row of chairs in the background. This makes the run-down glory of the Imperial, and of pre-tech-boom Oakland, an additional character in the book. You're not likely to read another comic this year that immerses you so deeply in the lives of a cast of characters, and these are lives — endearing, aggravating, tragic — that you don't see enough in modern fiction. Cartoonists like Pond are happily taking up the space that novelists have abdicated.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 13th - September 19th

Wednesday September 13th: The Hope of Another Spring Reading

An art historian named Barbara Johns offers a little context into the life of Seattle artist Takuichi Fujii, who passed away in 1964. Johns’s latest book revives this little-known artist whose remarkable life includes a stint in the Japanese interment during World War II. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday, September 14th: Scream for Zines! Mini Pop-Up Zine Show

As part of Capitol Hill Art Walk, a collection of Seattle-area zine and minicomics greats are selling their work. Featured artists include Eroyn Franklin, Jazzlyn Stone, Emily Denton, and Michael Heck. Plus, the invite says something about enjoying “a complimentary drink,” so make of that what you will. Scream, 819 E. Thomas St, 861-8468, http://screamseattle.com/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday September 15th: Hugo Literary Series

The Hugo House’s crown jewel reading series, in which a mix of local and national writers make new work on a theme, kicks off for the 2017-2018 season. The readers include the downright brilliant Meghan Daum, the gifted poet Solmaz Sharif, and the underappreciated Seattle author Sonora Jha. They will all read new work based around the theme ‘Sequels.’ Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030. http://www.hugohouse.org. $10-25. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Saturday, September 16th: Love and Other Consolation Prizes Reading

Jamie Ford, the Seattle author who previously wrote a celebrated novel about the International District, returns with a novel about Seattle’s 1909 World’s Fair. It’s the story of a boy who is raffled off to a supposedly “good home” that turns out to be a brothel. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com. Free. All ages. 4 p.m.Sunday, September 17th: The Great Book Larder Bake-Off

This event is sold out, but there is a standby list, so there’s a chance you might get in. It’s a baking competition loosely based on the hit TV show the Great British Bake Off. Today’s event is themed around savory baked goods, and the winner receives a $50 gift certificate to the Larder. Book Larder, 4252 Fremont Ave. N. 397-4271, http://booklarder.com. Free. All ages. 4:15 p.m.Monday September 18th: The Twelve-Mile Straight Reading

In case you weren’t already aware, the South is deeply fucked up. Aside from being badly beaten in the Civil War and never really getting over it, there’s a roots-deep racism that infects everything. Eleanor Henderson’s second novel is set in rural Georgia in the year 1930, which was an especially fucked up time. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Tuesday September 19th: Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Five books by Seattle authors to look out for this fall

Timber Curtain by Frances McCue

Last year’s Ghosts of Seattle Past anthology, it turns out, was just an appetizer for this main course. Like Ghosts, Seattle poetry master McCue’s new book is a lament for the demolition of the Hugo House — an organization which she helped found. Though the House will soon return to the same spot (albeit in the ground floor of a fancy new building) McCue knows that nothing is the same once it passes through the veil of nostalgia she calls the timber curtain. This 100% made-in-Seattle production is published by local press Chin Music, who really know how to put a gorgeous book together. (Chin Music, September 4th)

Season of Sacrifice: A Maya Mallick Mystery by Bharti Kirchner

Bharti Kirchner is one of Seattle’s most prolific authors, with seven novels, four cookbooks, and an uncountable spray of short non-fiction pieces to her name. But Kirchner always somehow finds the time and the energy to make something new. Her latest novel, Season of Sacrifice, is her very first mystery, and it’s intended to be the first book in a new series featuring “feisty Asian-American private investigator Maya Mallick.” In her debut, Mallick encounters two women dressed all in white who set themselves on fire in the Green Lake neighborhood. (Severn House Publishers, September 15th)

In Between by Mita Mahato

If you’ve ever been to the Short Run comics festival, you’ve probably encountered (and been blown away by) Seattle cartoonist Mita Mahato’s gorgeous papercut comics. Mahato uses the tactile vibrancy of paper itself to tell her stories. (“Hitched,” her minicomic about a road trip, for example, was printed on top of a map.) Mahato’s first bound collection of comics, In Between, will expose her work to the wider world, and help to redefine the art of comics for a new generation. The odds are good that Mahato is about to break big; her voice is unique, and it’s impossible to resist. (Pleiades Press, October 2nd)

A Lesser Love by EJ Koh

Seattle poet E.J. Koh has been one of the up-and-coming lights of the Seattle poetry scene for a couple of years now. She would rise to the surface, publish an astonishing poem, and then go away for a while. At Bumbershoot 2016, she read a poem about the Korean ferry disaster that left the audience in tears (it was so quiet in the room, you could hear the individual sobs.) Now, she’s ready to make her mark with her debut collection: A Lesser Love. This marks a major rite of passage for Koh, one that should elevate her to Seattle poetry star status. (Pleiades Press, October 16th)

Chief Seattle and the Town That Took His Name by David M. Buerge

While most Seattleites know Chief Sealth’s name, ask just a couple of questions and you’ll realize that their knowledge only runs surface-deep. Subtitled The Change of Worlds for the Native People and Settlers on Puget Sound, Buerge’s book claims to offer “the first thorough account of Chief Seattle and his times.” It documents the historical inflection point when European-American settlers arrived and, through guile and violence, claimed this land as their own, as well as the way Sealth responded after his land was taken from him. This portrait could redefine the origins of Seattle for a generation. (Penguin Random House, October 17th.)

Literary Event of the Week: Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian Reissue Release Party

Sherman Alexie published a letter to his fans on Facebook in mid-July. It was about his book tour for his memoir about his mother’s death, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me. Alexie was being haunted by his mother, Lillian. Alexie interpreted these repeated visits — in the form of coincidences and visions and emotional distress — as a sign. “I am supposed to stop this book tour… I am cancelling all of my events in August and I will be cancelling many, but not all, of my events for the rest of the year,” Alexie wrote.

“Dear readers and booksellers and friends and family, I am sorry to disappoint you. I am sorry that I will not be traveling to your cities to tell you my stories in person,” Alexie continued. He was clearly a man who was deep in the process of grieving, and he puts so much into his readings that he was tearing his soul open every night he took to the stage.

But Alexie wasn’t about to become a Salingeresque recluse. “My memoir is still out there for you to read,” he wrote. “And, when I am strong enough, I will return to the road. I will return to the memoir. And I know I will have new stories to tell about my mother and her ghost. I will have more stories to tell about grief. And about forgiveness.”

But if you know Alexie’s story at all, you know that there are two things that he loves more than almost anything: his home and his audience. While reading from Love was too much for him to bear, anyone who has seen Alexie read knows that he draws strength and inspiration from being onstage, from interacting with an audience. And anyone who has seen Alexie read in Seattle knows that he draws a special power from a hometown crowd.

So on Tuesday, September 19th, Alexie is returning to the stage for a special reading — not for his memoir, but for the tenth anniversary of his blockbuster young adult novel, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. Alexie was already a famous author by the time Part-Time was published, but the book broke him into the mainstream in a way that’s usually only reserved for rock stars and Kardashians. The book, which talks frankly about masturbation and other sexual topics, has been banned repeatedly from school libraries by fussy Christian parents, which has only inspired more sales and made Alexie even more famous.

So for one night, Alexie is going to get back on stage where he belongs, and he’s going to soak up his hometown audience’s affections, which is exactly as it should be. It’s more important than ever to go and be a part of the Alexie experience, to show him how much Seattle loves him. This time around, Alexie needs us almost as much as we need him. Let’s not let him down.

Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Song of the South

Published September 12, 2017, at 11:59am

Even Joan Didion's unfinished story notes are absolutely motherfucking perfect.

A poem is a space

and an unspace

It is all and half of all —

a third of half

and a tenth of that

A poem floats — spaceless

yet touches a finger,

an eye, lips and a hand.

A poem’s content

and form are sublime

yet, narrow and broad

A poem is speechless with sound

Such is ambiguity — it lives in every act

Therefore, the poem is an act — an event —

An event is an act — is a poem

— and more —

We're only living this instant

The title says it all: Blip. That's how long we've got, here. When sponsor Ken Boynton was in a nearly-fatal car accident, his perspective changed. Blip was his way to communicate his new-found awe for our short time on this planet.

See six spreads from this short, important book on our sponsor's page, and take a moment to consider your awareness of this moment. Like one reviewer on Amazon said: "...this book should be read by everyone multiple times."

Sponsors like Ken Boynton make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know we sold out our last sponsorship run? We're booked solid through February 2018, but if you have a book, event, or project you'd like to get in front of our readers, reach out and let us know. We'll be able to crack open our calendars and reserve you ahead of the pack.

An imperfect Circle

Aside from A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers’s most influential book is probably his novel The Circle. When it was first released, the novel was derided by many in the tech sector for its unrealistic depiction of day-to-day life at a giant Google- or Facebook-like tech company. But in the years since, readers have responded viscerally to the sense of decaying privacy that pervades the book.

The Circle was never meant to be read as a tell-all roman á clef; Eggers obviously intended it to be a cautionary tale — a modern version of 1984 or Brave New World, only set about two weeks in the future instead of several decades. And Eggers nailed the creepiness of The Circle’s corporate culture: the forced “voluntary” participation, the demands to always be available to social media, the cheerful demand to stay in lockstep with the company’s ever-expanding goals and ambitions perfectly emulate what it means to work at Google or Facebook or, to some extent, Amazon.

The film version of The Circle — now out on DVD or, if you’re into irony as a delivery system, available to rent from your favorite streaming media platform — enjoys a few benefits that Eggers’s book did not on its release. For one thing, the mild science fiction premise of the book has now basically come true. The Circle’s founding vision of society as a panopticon is no longer a threat – it’s our daily life. And for another thing, it’s got a charismatic cast ready to sell the idea to you: Emma Watson stars as Mae, the protagonist; Tom Hanks and Patton Oswalt play the founder and CEO of The Circle; Bill Paxton, in one of his final roles, plays Mae’s ailing father. This is a cast most audiences would be willing to follow anywhere, and with good reason.

But the film version of The Circle proves that the story is better off as a novel, even though Eggers himself cowrote the screenplay. The best part of The Circle is the way the digital world slowly insinuated itself into the real world. In the book, Mae would return to her desk only to find someone installing another screen to keep track of some new flow of information; in the film Mae is overwhelmed by the second screen to be added to her desk, and then she suddenly has five screens a scene or two later. The monotony of Mae’s job — she’s basically tech support — comes through in the novel but not in the film.

And the plot, which in the book develops organically and across hundreds of pages, moves way too damn fast in the film. The story feels forced and improbable as a result. John Boyega’s character floats into a few scenes, charms Mae, and then disappears to the back of a few crowd shots, glowering his disapproval from hundreds of feet away. A supporting character’s death feels unearned. Mae’s emotional development is herky-jerky and inconsistent. It’s kind of a mess.

Obviously, you should read the book instead. That said, if you’ve read the book and you’re curious, the film version of The Circle is well worth watching. Those early scenes that lampoon Silicon Valley’s chirpy brand of conformity are funny as hell, and Watson’s performance is strong throughout. Even though it’s wildly uneven and ultimately unsatisfying, it’s more thought-provoking than many of the emotionally manipulative films that wind up getting nominated for Oscars.

Visiting the first Readerfest

Seattle’s first Readerfest — a book festival brought to life in record time by Karen Junker — took place Saturday at Magnuson Park, in The Brig. I’m assuming the building actually used to be a brig. It's a building that comes together at angles, wings converging on a boxy center. The keynote took place in the Matthews Beach room, the "beach" part evoked by colorful murals on the painted cinderblock walls. Tables, with black cloths and flowers, set the stage where keynote speaker (and Seattle Review of Books columnist) Nisi Shawl spoke to the small crowd who made it in time to hear her introductory remarks.

Shawl — and emcee Ashley Lauren Rogers, in her introduction — made an early point of acknowledging that we were gathering on native ground, after which she read her prepared remarks. She talked about Trump, or rather, how he has affected writers. “Trump’s presidency has done us harm,” she said. It has also led to a strong uptick in the amount of anthologies sending her requests for work, most of which are resistance themed.

But creating is hard when the news is a constant deluge of shocking inhumanity. Some call those who are affected by our administration "sensitive", and she had words for them: “Sensitivity is a tool as well as a wound. Sensitivity is vital to the process of writing: I write with all my senses turned up to eleven… I write with my heart.”

There was plenty of heart on display in the gathering of authors, publishers, and booksellers. I browsed the tables, stopping to chat with Balogun Ojetade who was showing his Afrofuturism gamebooks, and RPGs (although he’s also a novelist and screenwriter). His work covers grand themes of fantastical black experiences and look like a lot of fun, to boot. Read the description for Dembo’s Ditty to get a feel.

Broken Eye Books was showing their work, so I stopped by to talk to publisher Scott Gable (SRoB co-founder Paul Constant reviewed their release of Adam Heine’s Izanami’s Choice last year). We chatted for a few minutes over a table chock-full of interesting work, like Desirina Boskovich’s Never Now Always, and their anthology of Lovecraftian sci-fi titled Tomorrow’s Cthulhu. They’re a publisher to keep an eye on.

Outside, in the cloud-covered day, tents were set up for events. I dropped in to hear a panel with Nancy Kress, Sonia Orin Lyris, Nicole Dieker, and Spencer Ellsworth talking under the banner of “What makes a story literary?” The conversation was lively and entertaining, but what made it particularly valuable was the opportunity to attend, in effect, a master class with Kress, one of the most accomplished and engaging science fiction novelists working today. We’re lucky to have her in Seattle now, and seeing her pop up at events like Readerfest shows how much attention they paid to who they invited to speak.

Another thing Readerfest got right was inclusivity and diversity. Nicole Dieker said that for her, “the best part of Readerfest was its emphasis on inclusivity and representation." If you didn't get a chance to see the programming slate, take a look — from the choice of speakers to the panel topics, it's clear that Readerfest is actively working to amplify #OwnVoices and go beyond the usual "here are a bunch of panels about X, and here's one panel called women in X and another one called diversity in X" approach." At Readerfest, inclusivity wasn't pushed into one panel. It was a central part of the convention.

Still, around the edges, the youth of the festival showed. Although the food trucks looked delicious, they didn’t offer a lot of variety, and I know at least one person who wasn’t able to get food that fit their dietary needs. The signage when approaching the venue was too sparse, and confusing. The layout of the space was strange enough that maybe a table out front to welcome people, next time, would be welcome, as would maps — it took a bit of exploring to find everything.

Maybe that’s what you get for pulling together a festival in record time. With a whole year in front of her, I’m certain that Karen Junker, the driving force behind Readerfest, can pull off something on a bigger scale. One person I talked to said the event felt like “rehearsal for the real event,” and that seems about right.

But small certainly has its charms, too. The vibe was a bit like wandering into the back halls of a science fiction convention where some great conversations were taking place out of the limelight, and that was a welcome feeling. There was time, and opportunity, to connect with the people you wanted to.

In her keynote, Shawl recalled Octavia Butler, and how if you look through Butler’s papers at the Huntington Library, you'll see that she was deliberate about her work and intention. She used affirmations to guide herself toward the future she wanted, the future she built. So, following this example, Shawl offered us four affirmations, which we listened to her speak, then all spoke together, as an invocation to close her secular sermon.

- We are beautiful, and we have every right to glory in our beauty.

- We belong where we're going. We're getting there

- We have important stories to tell, and important ways of telling them

- We live in love.

Here’s to the foundations of Readerfest, and to its future, built one reader at a time. All are welcome.

Never trust Aaron Burr and other research tips from a historical romance author

Writing a historical romance novel involves a staggering amount of research. How corsets work, where to throw away that apple core, what kind of naughty words people would use to describe what they’ve done with or to their lovers. We all do the work, but few of us do it as thoroughly as Rose Lerner, whose vivid Lively St. Lemeston books center around the people and events of one small English town. The latest novella in the series, A Taste of Honey comes out September 12th. This interview has been lightly edited.

For the new folks, let's start with a brief introduction to your own romances and particular areas of expertise.

My name is Rose Lerner and I write historical romance, typically set during the English Regency (a flexibly defined time period but I stick to the technical 1811 to 1820). For my current small-town series I've researched politics, high and low, and women's participation therein; queer experiences; the Napoleonic wars; Jewish life; servants; and much more. I also caught Hamilton fever for a while there and devoured books about Hamilton and Burr, and I've got a Jewish Revolutionary War romance coming out in October in an anthology with Courtney Milan and Alyssa Cole.

Do you research before, during, or after you draft?

All of the above. An actor that I love, Nicholas Lea, once said in an interview that he has to make a lot of little decisions in the moment, and research helps him make those decisions. That's how I write. I have a broad idea of the plot when I start a book, but beyond that I pretty much get in character and feel out the story as I go. I research until the POV characters' world feels solid to me. Then I start writing. Sometimes I get stuck and can't continue a scene without information, and then I need to take a research break. Little things, like whether "bear hug" is an anachronism (it is, but I decided to use it anyway) or what the heroine would do with an apple core after she'd eaten the apple (toss it in the fireplace grate, probably), I usually leave a note for myself in the text and research during revisions.

Do you prefer primary or secondary sources, when you have the option?

I read almost entirely secondary sources. Primary sources are great but you have to sift through so much irrelevance! I'd much rather have a trusted middleman pick out the important stuff for me. Of course, how do you know when to trust a middleman? I do like my secondary sources to footnote heavily so I can confirm in the primary source myself if necessary. But can you really even trust a primary source? If it's Aaron Burr, absolutely not. The key, to me, is to read enough that you develop a bullshit meter of your own.

Are there special considerations or pitfalls when you're researching the kind of sex people had in the past?

The pitfall, I guess, is that people talked less openly about the sex they were having in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Which may not even be true! What I can tell you with confidence is that what they DID say was extensively and often irrevocably expurgated, if not by family members immediately after their death then by Victorian descendants. The partial or complete destruction of letters, journals, and memoirs by burning, cutting away, or inking out potentially embarrassing content was common, especially if the writer was queer and/or a woman.

But based on what we do know through erotic novels, pornographic art, and surviving primary sources, it seems like they were having more or less the same kinds of sex we have now: kinky, vanilla, queer, with sex toys, role-playing, using birth control, threesomes, polyamory, whatever. Specificity is important and sexuality is culturally constructed, but at the same time, 98 percent of the time if I hear someone say, “But people didn’t do that back then,” my bullshit meter goes off.

Sure, this masturbation club where new members had to present their dicks on a silver platter does seem a little — quaint. But even there — the details are weird and incomprehensible, but the spirit isn’t that unfamiliar, is it?

How do you approach the language in your sex scenes, considering that historical gap? Writing about queer or kinky sex set before the modern terms were developed, for instance, or the frequent romance-author lament that there are a million period-appropriate terms for the penis and almost none for the clitoris.

Well, I don't see this as much more of a problem for queer or kinky sex than any other kind, because the terminology for ALL sex has shifted enormously. I have finally given up on finding good period terms for oral sex, and if I feel like "pleasuring him with her mouth" is too coy in context, I just use "suck" even though it's first attested in reference to fellatio in 1928.

It’s a delicate balance. A huge part of the appeal of historical romance is a sense of otherness, of distance, of experiencing the world as it might have looked to someone 200 years ago. I try very hard to retain a sense of how my characters THINK, and in particular how they think about sex. I try to think about where they would have gotten their information about sex and what words they would or wouldn’t know or feel comfortable using. I used to hate “pearl” for clitoris and think it was unbearably precious, but I’ve finally given in (although when I’m writing a well-educated hero, I usually just say “clitoris”). Sometimes I’ll even purposely choose an older-sounding or obsolete word when a more modern one is available. For example, “to come” meaning to have an orgasm is attested from 1650, but I frequently opt for “to spend” instead, because I think it gives things a nice period atmosphere.

At the same time, in my opinion TOO much authenticity in a sex scene can be off-putting. I try hard to avoid anachronistic word usage (or at least, distractingly anachronistic word usage, or word usage that represents a shift in conceptualizing something). But about once a book, I give up and use “sex” with its modern meaning of sexual intercourse, simply because in that sentence I tried out “coupling,” “congress,” “bedsport,” “coitus,” etc. and hated the way all of them sounded.

If I wrote “he larked her,” the reader would be confused, and if I wrote “he larked between her breasts,” she’d probably get the point, but she’d laugh. I just don’t see the point of privileging this kind of academic accuracy over storytelling. It’s a sex scene, and it should be sexy.

More about the general vs. specific — how do you balance the broad general statistics ("most people of the time/place would have — ") with the specific examples and the outliers? ("A few exceptional people did — ")?

For something like, "Could my heroine have a front-lacing corset?" this is a pretty simple decision (she could, but probably wouldn't) and in the end, it really doesn't matter either way. I'd probably go with the more likely back-lacing option unless I had a strong story reason to want her corset to unlace in the front (she doesn't have anyone to help her get in or out of it in a particular scene, or I want to realize a specific sexy image).

But this can get pretty political. Whether your character is an outlier or not, you still have to ask yourself, “Why is this the story I am choosing to tell?“ The choice to tell an average story can be just as loaded as the choice to tell an exceptional one, and ”Well, it’s historically accurate“ is never a sufficient justification for anything. I’m sick of hearing, ”They were a product of their time," to justify some atrocious behavior in a historical figure. Literally everyone who has ever lived was or is a product of their time. That’s how time works.

History is not neutral or objective or absolute, any more than memory is. It is the compilation and interpretation of millions of stories. Just because one story has been told more than another, it isn’t necessarily truer. Just because one side of a story has been heard more than the other side, doesn’t make it the “more accurate” side.

An unloaded example: when Aaron Burr, in his old age, tells a friend an anecdote about something that happened between him and Alexander Hamilton fifty years earlier, and then ten years after that the friend writes it down, you shouldn’t take what you’re reading at face value as the truth. (That should be common sense, and yet I see those stories repeated as fact by reputable historians.)

When it comes to history, the same logic applies to basically everything: You have to have common sense. You have to keep an eye out for motivations and agendas, both in yourself and other people, because they’re always there.

You have to be aware of your own agenda. And you have a responsibility to think about whether your agenda hurts people. You have to ask, “Why is this the story that feels true to me?” and then, “Is that a good reason?"

I’ve noticed that my books with queer or Jewish main characters get labeled “anachronistic” in reviews more frequently than my other books, despite my knowing that I put a similar level of care and research into all of them.

Why are so many readers attached to the idea that the average Jewish person in the Regency led a tragic life? And even if you take that as fact (which I don’t), why are they attached to the idea that I should be telling that “average” story when a romance novel is, at heart, a wish-fulfillment fantasy? There were about thirty-one dukes in the UK during the Regency, out of a population of about 15 million (source). Meanwhile, the Jewish population in England in 1800 has been estimated at 15,000. I think my odds of finding real historical examples of young, attractive, happily married Jews are a little better than yours of finding young, attractive, happily married dukes! Yet I’ve never seen a book labeled anachronistic simply because the hero was a duke.

Like a lot of issues in romance, it's an amplification problem. A trope becomes popular and obscures the reality, or mistakes get repeated and then become "common knowledge" in the readership. Historical romance author Miranda Neville recently described the Regency romance as "a long game of telephone starting with [Georgette] Heyer — who is foundational, but also notorious for the classism and anti-Semitism of her books. How do you balance uprooting that negative tradition versus providing something more nourishing to your readers? I guess what I'm asking is how much you see your work opening up a neglected space in the past, versus creating a new tradition for future readers and authors?

I'm not sure I think about it in those terms. Based on my email inbox, I've inspired some other folks to start writing Jewish historical romances, and that makes me happier than just about anything. But I don't write with that in mind. I just write the stories I would want to read.

Genre conventions are there to guide the reader through the story. Following them is part of the bond of trust between writer and reader. I would never write a romance novel without an HEA [Happily Ever After], for example. But when a convention is just plain incorrect (or worse, unjust), then I think I actually owe it my readers NOT to follow it. What matters is not the fact of breaking a genre convention, but whether it’s done in a spirit of love and respect — for the genre, and for the reader.

I’ve read a LOT of Regency romance throughout my life and I have a lot of affection for its conventions, but at this point, if I know Heyer was wrong, I feel very comfortable ignoring her.

This isn’t what you’re asking, but it made me think of it — I once got a rather anti-Semitic review of True Pretenses that suggested, essentially, that in creating a positive portrayal of a Jewish man, I was fighting an uphill battle against the weight of anti-Semitic stereotypes in literature and necessarily closely engaging with those stereotypes as I made character choices. This, to me, is bizarre; it assumes that classic English novels and Georgette Heyer are the only literary traditions there are — and even beyond that, they are the only frame of experience I have to draw on!

In fact, I have not only read and seen many positive portrayals of Jewish men by modern Jewish authors and screenwriters, but I have also KNOWN NICE JEWISH MEN IN MY ACTUAL REAL LIFE. This is also true for plenty of my readers (although not, apparently, that one). While it’s nice to be genre-aware while writing genre fiction, and I absolutely adore playing with tropes like marriages of convenience, fake dating, Cit heiresses, starchy butlers, house parties etc. etc., the Regency romance genre is not the entire context readers are bringing to the table.

If I know something might confuse a reader because it’s not the commonly accepted “truth” of the past, I try to include a little more signposting and explanations. But I’m not going to write beady-eyed moneylenders with greasy sidecurls just because Georgette Heyer did.

If I could summarize all my thoughts about history in one sentence, it’s this: the truth matters.

The truth always matters.

But the past is composed of a million intertwining truths. “People in the Regency could have great sex” and “people in the Regency thought about sex differently than we do” are both true. “Anti-Semitism was rife among Christians in the Regency” and “there was plenty of intermarriage between Jews and Christians in the Regency” are both true. As a author of historical fiction, my job is to decide what the most important truth is at a particular moment.

The Sunday Post for September 10, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Voynich manuscript: the solution

This week, a credible solution to the most mysterious manuscript of all has been put forth. Is the Voynich manuscript a private home-remedies manual for a well-to-do woman? Nicholas Gibbs certainly thinks so. I think Maria Dahvana Headley said it best:

I'm going to be cackling & bouncing around the room if indeed the Voynich is a 15th century Our Bodies, Ourselves. https://t.co/eXM3uCSGc4

— Maria DahvanaHeadley (@MARIADAHVANA) September 8, 2017

For medievalists or anyone with more than a passing interest, the most unusual element of the Voynich manuscript – Beinecke Ms. 408, known to many as “the most mysterious manuscript in the world” – is its handwritten text. Although several of its symbols (especially the ligatures) are recognizable, adopted for the sake of economy by the medieval scribes, the words formed by its neatly grouped characters do not appear to correspond to any known language. It was long believed that the text was a form of code – one which repeated attempts by cryptographers and linguists failed to penetrate. As someone with long experience of interpreting the Latin inscriptions on classical monuments and the tombs and brasses in English parish churches, I recognized in the Voynich script tell-tale signs of an abbreviated Latin format. But interpretation of such abbreviations depends largely on the context in which they are used. I needed to understand the copious illustrations that accompany the text.

Twenty-Six Notes on Cannibalism

Seattle writer, and Seattle Review of Books contributor, Anca Szilágyi walks a numbered path for the Los Angeles Review of Books, detailing her observations of Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son, and in doing so recalls Sontag, Berger, and others. She explores how a painting evokes both a method to the artist, and an evocation of historical moments foretold.

4. Saturno devorando a su hijo is different from Francisco Goya’s other works, such as early portraits of royalty or even later etchings sharply critical of the atrocities of war. It is one of the Black Paintings affixed to the walls of his home, Quinta del Sordo (House of the Deaf Man), which he bought in 1819 at age 72. These paintings were not commissioned. They were not for sale. No one saw them until after his death. The artist’s fear is in Saturn’s eyes.

The Department of Justice Is Overseeing the Resegregation of American Schools

Thought it was gonna be all medieval ciphers today and explorations of dark paintings today? Sorry, and welcome to the nightmare of our modern backslide into mid-century unexceptionalism, racism, and horribleness. Turns out, white parents will segragate their schools again. Because reasons. Emmanuel Felton reports on this very thing for the Nation.

See, also, the New York Times Magazine take on the same issue.

Speaker after speaker complained about how the city had been portrayed. This wasn’t about race, they insisted, but about doing what was best for “our” children. But Williams knew that her children weren’t included in that “our.” Just the night before, at a meeting in her own neighborhood, Jefferson County’s superintendent presented Williams and the other parents with a list of schools their kids could choose if Gardendale left the district. All of the schools served more black and poor students than Gardendale’s, and all had far worse test scores. At the Gardendale meeting, Williams stood by quietly until she couldn’t take it anymore.

As she headed to the front of the packed hearing room, Williams felt glad that she had dressed up. “I’m a product of the schools they don’t want my children to be at,” she said later. “I wanted to be a perfect example of why they should include them.”

You Are the Product

John Lanchester writes about Facebook for the London Review of Books. He is decidedly not a Millennial digital native, but as Facebook switches from being a successful startup to a world-dominating force, holding them to a high standard becomes absolutely critical.