This summer brought to you courtesy of ...

Love a little, die a little, and break the law. Trey Milligan did them all in one summer, and before his 14th birthday. Sponsor Frank Murtaugh's debut novel, Trey's Company, was just released this month, and we've got a sneak peek to share with our readers — the intro and whole first chapter – perfect timing for your summer reading list. Baseball and coming of age are a common pairing; with his background in sports writing and intimate knowledge of the story's locale, Murtaugh brings something special to the mix.

Sponsors like Frank make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. We only have three openings left in our current block! Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Book News Roundup: The deadlines approacheth

Hey, Seattle writers! Please remember to apply for the LaSalle Storyteller Award, a fantastic $10,000 award from Artist Trust that goes to "an individual literary artist working in fiction." This is a lot of cash with very few strings attached, so it's one of the finer fiction prizes in the region. More information at Artist Trust's site.

And if you'd like to take a writing class this summer, you should know that today is the last day for early bird pricing for any of the Hugo House's summer class schedule. Sign up here and get anywhere from $10 - $35 off of your classes.

You should read this terrific profile of Sherman Alexie by Anne Helen Petersen at BuzzFeed:

There’s a strong overlap between the women of the anti-Trump resistance and Alexie’s readership, which is primarily composed of college-educated white women. Unlike some male authors (see: Jonathan Franzen) who worry that a female audience will feminize their art, and thereby delegitimize it, Alexie embraces his readers. “They pay my mortgage!” he said. “But they’re also just more open to actually crossing boundaries. They have that perfect combination of privilege — because of their whiteness — and oppression, because they’re women. They’re at the forefront of every battle, and they come into it with both strength and weakness, with both power and pain.”

If you're into best-of lists, Vulture has published a listicle of "The Best Books of 2017 So Far." The usual standards apply — lists are meaningless, you can't really rate literary works, lists provide nothing more than clickbait for media sites that are addicted to clicks at the expense of thoughtful coverage, etc. etc. etc. — but sometimes lists of this sort spur bookstore shopping excursions, and who am I to argue with the buying of (and/or library-checking-out-ing of) new books?

OpenCulture published a great piece about why lowering your productivity might actually lead to better work. If it was good enough for Charles Dickens, it's good enough for you.

The Harry Potter books are now 20 years old.

Uncovering the true stories of Salish native women and intercultural marriage

WSU Press just published the first book by Bellingham-based historian Candace Wellman. The full title gives you an idea of the topic: Peace Weavers: Uniting the Salish Coast Through Cross-Cultural Marriages. It's a book that follows the life stories of four indigenous women who married across cultural lines, making families with pioneer men.

While the fact of cross-cultural marriages was well known, the women in them were ignored, seen as appendages of the men, or cast in racial and gender stereotypes. It took a curious outsider to start questioning the assumptions of previous historians, and uncover what in retrospect is a seemingly obvious truth: these women had complex, rich lives, and their own stories to tell. Something more remarkable: Wellman uncovered pasts that none had bothered to look for. Outside of family histories, this is the first time their lives have been told.

By focusing on four women, Wellman was able to tell a rich story of life in 19th century Washington and investigate many heady topics that seem to be evergreen: the purpose of marriage, and what it means to marry outside of your race and culture.

I sat down and spent a nice morning with Wellman, who (in the strangest disclosure I've been impelled to write to date) is the mother of my first high school girlfriend. The transcript has been lightly edited.

This was an 18-year journey for you.

Right.

Every author I talk to, there's always that one spark that started them on the journey. In this case, a long journey with a lot of research for you. What was that initial spark?

I was a volunteer research assistant at the state archives in Bellingham, and one day a woman came in — she was from Montana, camper was out in the parking lot. She said, "My great-great grandmother was an Indian. Her name was Mary, and she was married to John Briggs here, and that's all we know about her. Will you help me find my family?" So we worked on her genealogy that day.

Six weeks later, another woman on vacation came in, and she said, "My great-great grandmother was an Indian, her name was Fanny. Would you help me find my family?" When we worked on her, I found that those two couples had been married together in the same house on the same day. That was the connection between those two couples. I thought that was really intriguing. Then I found a list of all the people who had been intermarried in the 1850s that was laying in this old historian, Howard Buswell's, files.

Then a newspaper reporter in Washington, DC, was referred to me for help on General Pickett and his Native wife. What I said to her was, "Everything that could be found out about her life was researched and published in the 1960s. There isn't any more." And she said, "Would you suspend that assumption and look again?" When I did, I found new information. So I said, "What else is out there about these other women that everyone thinks there's nothing out there about them?"

Suspending the assumption, as a starting point, is it looking at documents you've already looked at from a new point-of-view and looking for clues, or is it uncovering documents that you wouldn't have considered? Because you went to historical documents, you went to family documents, genealogical stuff. You had a wide variety of sources.

Huge variety of sources. It started off, I was going to write a two-year project about how the Native wives and the white wives lived together and helped each other in those very early years. As I worked, very quickly the white ladies, about whom we know a lot, became boring. And these other women became more fascinating, until I just decided to work on them. But one thing would lead to another. Like, I would take something that had been written about a husband, and I would just pick apart that paragraph and re-research everything. If it said "EC Fitzhugh went to Georgetown Law School," then I got hold of Georgetown and found out there was no law school at that time. It was a prep academy, which he got kicked out of.

If somebody said they went to West Point, then I checked with West Point and found out whether they did or they didn't. I just kept re-looking at everything. I started off with 22 women. Then I kept reducing it. If I couldn't keep the amount of information fairly even between husband and wife, then it had to go.

So the four women, was it kind of a natural evolution to whittle it down to the four women, or did you, at some point, have to pick between people you really wanted to write about, but maybe didn't have the time to, and these four women?

There are eight completed biographies. But the publisher wanted the book cut in half. Then I had to pick four. I looked for four that would give very different stories, very different looks at what was going on in the area, and what kind of lives they lived.

Can you talk a little bit about what marriages were like at that time in general? I think we carry a lot of 21st century assumptions about marriage backwards when we look at them. Or we have the historical assumptions that you talk about questioning. What was a day-to-day life like for a married couple in Whatcom County at that time?

That's the hardest thing to research, because men wrote about men's activities, and they didn't really write about what the women were doing. So it's very hard to pick and choose, and you have to look at what things were, in general. But what I found was that people keep saying that these cross-cultural marriages ... I actually had someone say to me, "But you don't think he really loved her, do you?" And they had been married for 30 years and had six children. There's an assumption that these men just sort of bought a girl to keep house, and be a sex partner, and have kids, and mend clothes. And that's not true. Because the families have their own agendas. You end up with two groups of women who are both in economic partnerships. The white women that came were not girls out of parlors in the middle of Boston. They were women who came west who could hold their own and be an economic partner.

On all the homesteads, whether the wife was a Native American, or whether she was white, they were all in charge of the gardens. They were in charge of the chickens. They made butter. They sold feathers. They sold butter. They worked just as hard as the mend did as an economic contributor; just at different tasks most of the time.

From 1854 to 1859, all the women who intermarried lived in one of three places: the mill, or mine settlements, or at Fort Bellingham. They had the company of many other women of both cultures. It appears that nearly all wives took boarders into their homes, which provided extra cash in a cash-poor economy. They housed, fed, nursed, and did laundry for working men.

You say "economic contributor," but also, in a sense, there was no other resource if you fell flat on something. You couldn't go to the store. There was no childcare. It wasn't —

Well, that's not completely true. Because the women took care of each other's kids. Even if they lived a mile apart, they were close friends. We didn't have doctors in this area until almost 1870, except for the military physician; the Army doctor at Fort Bellingham. Then, later on, he was clear over on San Juan Island. But he would come and help. Army doctors would run a private practice as well as their official practice, so they would help. But you had the Native women acting as midwives most of the time, and using Native medicines to help. You could also send for medicine to Victoria or down to Olympia. Seattle, in the early days, really wasn't anything. Everything was Olympia. It was, very much, the women had to help each other out here.

When you say early days, what's the —

The 1850s, 1860s, yeah. That's the period. But there might be one store, and that was it here. We went through a period where there were no stores here after the gold rush ended. Then the mine flooded and the mill burned down. Then there was nothing. So everything had to come from Victoria, or some other place. La Conner ended up with a little store.

Everybody was sort of living on the same level, for the most part. Struggling in little cabins, and then trying to build a house, and getting orchards in, and gardens in, and trying to find the crops that would go well here. Then you had the people that worked at the mine, had a little settlement, which could be dangerous with miners who were drinking on Friday night.

From what you know, then, what's the difference of life of being raised in a Native culture and living in — you talked about long houses, and some of the size of the long houses, then going to living in small cabins on pieces of land. Was there anything about that that you uncovered?

Well, the women talked about it being hard. It was really hard. However, one positive one was that when the families allied with these white county officials and military officers, the young women stayed pretty close to their families here. Because the custom, the Coast Salish custom, is to marry outside your village. So some young women would have been married clear up around Nanaimo and Duncan, BC, or much further south, and wouldn't have hardly seen their families, except perhaps yearly at a potlatch.

These girls were very close to home, so they saw their families all the time. That helped mentally. But they talked about loneliness; that it was lonely, when they were used to doing tasks together in the long house. The women would weave together and talk while they're taking care of the kids and stuff. All of the sudden, these young women are in charge of a cabin and children all by themselves.

And miles away sometimes. But closer, you say, than they may have been if they had married.

Closer than they might have been otherwise. That was a positive for the families; that they did get to see their mother on a regular basis, and their sisters and other relatives.

I think it's really interesting, you know, you talk again about assumptions that historians, or people reading about history, bring with them as they're reading about history. This book — it seems to me like it exists at an intersection of some really fascinating topics. I mean, first and foremost, the erasure of indigenous stories, but also diminishing of women's stories historically because they're told from a patriarchal point-of-view, or men are writing the histories. Also, the romanticizing of the American west, and the colonization of the west. Then, of course, the domination and kind of the decimation of existing cultures.

It's interesting because your book takes a more nuanced view on some of that. Which is not to say it ignores any of the truths that happened, but that kind of interweaving of cultures has been ... You know, I'd never heard of it before, obviously, and I think most people hadn't. Can you speak to that a little bit?

Yeah, well, this area up here in Bellingham was heavily dominated, about 90% of the marriages from the first 20 years from 1853 up until the early 1870s, about 90% of the marriages were cross-cultural. Then, when the history gets written, the women are gone for the most part. Other places were started by cross-cultural couples. I find a number of them in Washington. I know there's more that I don't have time to research. I believe they're all over the west; certainly Chicago, Detroit, Saint Louis, other towns like that, were started by cross-cultural communities.

Here it was so dominant because of the groups of men that came here; all these bachelors that came here and settled here. In other places, it might be just one or two couples. But the tip-off is always a community history that says, "The first white woman in town." Or, "The first white baby born here." That's the tip-off that there were cross-cultural couples there before. But people want the history to start with the all-American couples that have moved into the area. So they just ignored the others, wrote them out, failed to recognize contributions. I didn't expect to find this, but the longer I got into the research, the more I could see that this was going on everywhere. Just trying to find books to compare to my own for the book proposal, there wasn't anything out there, except over the border. Because there, they've written about the Hudson Bay company wives; fairly extensively. Although very few biographies that are wholly about the women. It's usually in conjunction to the male.

I think this went on everywhere, and it's just been pushed down in the name of the manifest destiny of America to conquer and own. I mentioned, like, in the Willamette Valley we talk about the Oregon Trail pioneers coming into this empty place waiting for them to settle. But when you go down to the Willamette Valley, you can go to Saint Paul, Oregon, and you find that they were fully engaged in building their brand-new, big, brick, Catholic church there in the middle of a farming community when those pioneers arrived with their wagons. It wasn't empty at all. There were communities; there were a number of communities. And big enough ones to have a brick church, not just a little shanty.

And some of the early communities here were Catholic, you mentioned. Is that correct?

Yes.

And some of the indigenous cultures took on Catholicism?

Yes. They were the only missionaries that were out here to the Coast Salish. Most of the Coast Salish, at least in the upper Sound, or lower Sound around here, were converted in the 1840s. The Swinomish Reservation church is the oldest parish in the state of Washington, I believe. The one at Lummi Reservation may be the second oldest parish. It wasn't until the 1870s that you really saw an influx of the Protestant missionaries deciding to come in, and a population that came in that were all-white couples moving in as the homestead laws took effect, and there was ground that they could settle on, and making some inroads on Catholicism. But you find most of the tribes around are still heavily Catholic, and have taken back their own religion, their own spirituality too, sometimes combining the two together.

You've mentioned that you had to thread a needle a little bit, just because there's some, potentially, really explosive issues here as a white woman writing about Native women, especially. I would imagine there's some sensitivities that you go into the writing with. Can you talk to that a little bit?

Well, there's a lot of distrust, because of disrespect that has been shown to the grandmothers when they were written about, and distrust because of people coming in, perhaps to do a dissertation at a reservation and promising a book when they finished, and then nothing every materialized. This amounts to theft of intellectual property, and that's the way they feel about it.

I tried to go at it as if somebody came to my door and said, "I'm writing a book about your great grandmother. Please tell me everything you know." I would be going, "Whoa! Who are you? What are your intentions? What kind of a book are you writing?" So it takes a long period of developing personal ties. My mentors at Lummi Reservation, I met at the first public program I ever gave. They mentored me through this whole thing. Chief Tsi'li'xw has never had any problem telling me when I'm going down the wrong road, or I should never say something again, or, "That's not the way to say it." Or I'm being disrespectful, and teaching me all along, all these years.

Other people, I have one Nooksack woman friend who I met early on, and she told me, "Listen to your heart and their spirits will guide you." So I always go back to that sometimes when I get confused or don't know what I want to do. Then I sit and think, "What would those grandmothers think of what I'm writing, or how I'm phrasing things? What would they want me to say?"

Many times it seems like you are exposing stories that have been left out, or sometimes in family histories, but sometimes completely left out of the historical record. That is almost the premise of your book.

Right. And there's resentment because of that too; that they knew how fully partnered people were here. In the early days, the Lummis and the Nooksacks controlled the entire transportation system on the Sound; unless you caught an Army or a Navy steamer, or something else that was here very, very rarely. Like, once every two months, if you were lucky to catch it, you could go up the Sound on it.

So, if you wanted to move your household goods, if you wanted to take a little trip to Victoria, if you needed to go to Olympia for the legislature, you were going to hire a Native canoe of the proper size to take you where you needed to go. This has been completely left out of the history in favor of Captain Roeder building the first boat here, but it was not the first vessel here at all.

You talked about Roeder as well, and a hidden history there that ... Can you talk about that a little bit?

Well, the founder of Bellingham is considered to be Captain Henry Roeder, and his partner Russell Peabody, who had a number of businesses fail in California in the Gold Rush, and they came up here looking to start a mill. They received permission from the Lummi to start a mill at the little waterfall hill. The Lummis thought that this would be similar to the Hudson Bay Company arrangements where people weren't really permanent, they weren't building towns, they were cooperative businesses. That's not what Roeder and Peabody had in mind at all. The next thing the Lummis knew, there was a little town growing around the falls, and they were being told to stay out.

Roeder himself married a Native American woman from Lummi. But when his fiancée from Ohio was due to arrive, he sent this woman and their two children back to Lummi, where they died. For that, his reputation among the Lummi is very bad. I think people in town that know our history don't know why his reputation is so bad out there. But that's because they don't know about this marriage; this first marriage, because it was kept secret for 150 years.

You were a bookseller?

A little.

A little. Does being a bookseller teach you anything about, or did you learn anything about getting a book out there, or how to present it, or any marketing?

Yes.

What did you learn?

That the spine of the book is extremely important, that you want a cover that catches people's eye immediately, that where they put the book in the store can make a great deal of difference. And booksellers like to talk to authors if you're not too pushy; if you don't bug them all the time. And if you can get booksellers to help sell your book, if you can get them interested in your book, they are your best advertisement.

My story is, when I was working at a bookstore here, was when Diana Gabaldon first wrote Outlander. Have you ever heard of that?

No.

Oh, it's a TV series now.

Oh, okay.

Okay. So the booksellers didn't really know what to do with it. It's a little fantasy, it's a little time-travel, it is romance, it is historical fiction. She was a professor of biology when she started this, and it was big, and nobody had ever heard of her. But booksellers, like me, across the country, started pushing this book. For instance, a commercial fisherman came in one day and he said, "I'm going out on the water for four and a half months. I need a little library to read while I'm gone."

So I helped him assemble a library of things that men like. I talked to him about his interests. We put together some military stuff, fiction, and all kinds of stuff, some spy thrillers and stuff. Then, at the end, after we had about 10, 12 books, he said, "Now, what is the one book you want me to read that you know I won't?" And I said, Outlander, and he took it. And he came back in four and a half months later and said, "That was the best book I ever read." But that's how she became ... Then her second book went right to the top of the bestseller list, and all eight have been. But that's the effect a bookseller who likes your book can have on sales.

Oh, that's great.

Is there anything else that you wanted to say or mention that I didn't ask about?

Oh, yes. "Were they really married?" I always am confronted with this question, every single time I talk.

And there was some legal ... You wrote about this a little bit. One of the fascinating things is, I had this thought reading about some of the court cases that you had talked about in the early days, and realizing how we're not so far from that with gay marriage today, or same-sex marriage. That some of the conversations sounded very similar. But yes, please.

The marriage laws in the beginning had started in the 1850s. The first ones were boilerplate, based on other territories. Then they started fiddling with it, because most of the members of the legislature had Native wives, and those laws would have disinherited their children. They wanted their children to inherit whatever land or property they had. Then they started fiddling with this and putting amendments in to the point where at one ... But then they didn't want to legalize Native marriage either.

It just became this tangled mess so that at one point, it was illegal to marry a Native woman, and it was illegal not to marry your Native wife. They put up a $500 fine on any clergy or public official who would perform such a marriage. $500 then is about $5,000 today, and none of these people had that kind of money. The Catholic missionaries did not. Nobody had it. The Catholic's attitude was the same as it had been with the Hudson Bay Company; that you would marry because you presented yourself to the world as a married couple, and you considered yourself married, and that, whenever a priest would come by and you were ready to formalize it, that's when you did it. They were very understanding about the conditions that were going on.

But then, in the 1870s, when the Protestant ministers and all those white women moved in, they had standards; social standards. They did not consider Native women ladies. They had these ideas between ladies and women, and if you were common. They saw these old settlers, as they were always called, the old settlers, as fornicators, because they didn't have paper. But in this area in the early days, this was just how everybody got married. It was tribal custom marriage: an exchange of obligations and gifts between the husband and the woman's family, and you were married.

Then start the legal cases. They were politically connected. They charged a bunch of these men with fornication, and these men had been married for 20, 30 years, had a whole bunch of children, and it would have ruined them. I mean, they could have sent them to jail for this. Some of the people went and got married. Some of them got married with paper, church, or whatever. Some of them just went down to the courthouse and got a license so they had a piece of paper of some kind and said, "I'm not doing this." But when it got stopped, the prosecution stopped when Henry Barkhausen, who was a former county auditor and had been an election judge, and a highly respected man, he said, "I'm not doing it. I am not remarrying Julia. She has been my wife for all these years. We've got six kids, and I will not shame her by calling myself a fornicator."

Then it went to the chief justice of the territorial supreme court who came out with this beautiful treatise on the nature of marriage, that it has nothing to do with government or religion; that it is a contract between two people, and being a religious man, he went back to Adam and Eve. He said, "If you negate that marriage, then you must negate all contracts that have happened in the world since then." And, "There's all these other societies that don't use paper. Are you going to say that none of those people are married?" So this put it to rest. The prosecution stopped, and all of the tribal custom marriages were declared legal.

What year was that then?

1879, I think the decision came down. They started indicting them in '78. And '79, I believe is the date that —

Do you know, did they actually enforce the fines? Were there fines levied against?

Don't know. Because it was such a mess with this you-have-to-and-you-can't thing that nobody knew what was going on. I don't really know. I just know that it was a terrible legal mess, and people just quit paying attention to any of it for a long period, and continued to marry by tribal custom, and some people married with the county, or a priest, or a minister. But others just went ahead with the tribal custom marriages, because nobody could tell what they were supposed to do.

The Sunday Post for June 25, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

San Francisco Is Burning

This one’s already causing a little online consternation (what doesn’t, these days?): Jon Ronson investigates whether a rash of fires in San Francisco’s Mission District could be arson, intended to drive out lower-income residents and make way for SF’s version of the epically sky-blocking tech towers that are springing up all over Seattle. Regardless of whether the fires are intentional or just ancient wiring and insulation, it’s a sign of the times that we’re ready to think this might be true. Average joe vs. rich developer is a longstanding David-and-Goliath trope — but has it ever been as widespread and divisive as it is right now?

For five days, Gideon was going to be an arsonist: “Five days between me meeting the guy and, bam, the cops knocking on my door.”

To his credit, The Mountain View was supposed to be empty on the day of the planned fire. His insurance company had been paying his tenants “to get the fuck out of the building.” And they were relocating. “They were taking off like roaches,” he says.

Half an hour ago, Gideon referred to his residents as pigeons. Now they’re roaches.

How close are we to doomsday?

Periodically the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moves the hands of the Doomsday Clock, reflecting a shift in world currents that brings us closer to (or farther from — wouldn’t that be nice?) “destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making.” It’s a powerful visual metaphor to express that we’re nearer now to self-destruction than at almost any point in past 70 years. Oliver Pickup tracks the clock’s history and the reasons behind the recent 30-second jump toward midnight.

At this precise moment we are the closest to the apocalypse since the 1950s, a twitchy period when Cold War combatants, the United States of America and the Soviet Union, were doggedly pursuing the hydrogen bomb. At least that’s according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ symbolic Doomsday Clock, which sparked global alarm when it ticked forward to two-and-a-half minutes to midnight in January.

More worrying still, the 2017 time setting was determined before North Korea’s recent spate of nuclear missile tests, and climate-change denier Donald Trump’s erratic presidency, which has re-chilled Russian-American relations, had begun in earnest.

The original design of the clock, featured on the cover of the Bulletin in 1947, was revised a few years ago by Michael Beirut, who also designed the iconic logo for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential run. That story in more detail here.

How letterpress printing came back from the dead

It’s a little sad to see the renascence of letterpress printing credited to Martha Stewart — at least, for those who love not just the output, but the messy, painstaking process, the geekery of platen vs. cylinder, the mind-bending complexity of thinking about language through a mirror and in three dimensions. If you can forgive Glenn Fleishman the sin of attribution, here’s a good piece on Seattle’s still-growing letterpress scene and how digital technologies are changing the throwback industry.

Though letterpress might seem like yet another expression of a society hankering for artisanal, one-of-a-kind goods in an era of endless, identical reproduction, this return to the past is different. Beneath the old-timey patina of letterpress goods is a full-scale digital reinvention that drags Gutenberg’s great creation into the full embrace of modern technology.

Night Life

Doomsday, arson, gentrification, and the tech industry in everything … In case this week’s post is too much like your Twitter feed, here’s something thoughtful, solitary, and just a little bit quixotic: Amy Liptrot spent a summer on Orkney Island, trying to heal her life and counting a rare, endangered bird she never saw. After dark, the world transforms itself, and she has just the right voice to help us hear it.

I am the night listener. My woolly hat pushes my ears forward. I chew no gum, wear no rustling clothes. The work is repetitive — driving to the next stop, pulling in if possible, turning off the ignition, winding down the windows, consulting the map and noting down the grid reference. Then I wait for the noise of the car engine and my head to subside, and the sounds of the night to reveal themselves.

What does it mean for a journalist today to be a Serious Reader?

Most of the writers interviewed for Danny Funt’s article on the necessity of serious reading to good journalism have appeared in the Sunday Post at one point or another. The perfect mashup for Seattle Review of Books readers, as well as a strong argument in favor of reading as as a practical way to interact with the world. Probably not a discussion we need to keep having, but this is an interesting version of it.

I spoke with a dozen accomplished journalists of various specialties who manage to do their work while reading a phenomenal number of books, about and beyond their latest project. With journalists so fiercely resented after last year’s election for their perceived elitist detachment, it might seem like a bizarre response to double down on something as hermetic as reading — unless you see books as the only way to fully see the world.

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Olympic Sculpture Park

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

In Bellingham, on the campus of Western Washington University, is a remarkable collection of public art. I spent many hours wandering and hanging out — sometimes hanging on — that art as a teenager. There was something that felt, in an ambiguous and hard-to-quantify way, truer spending time there than hanging out at, say, the mall. Guards would kick you out of either, but at least the WWU didn't care if I bought anything.

So when I moved to Seattle, I loved to visit the public art. There is quite a bit, although it wasn't collected in one convenient place. You could visit the Sound Garden at NOAA, at Magnuson Park (although, now doing so requires a photo ID), or the Black Sun in Volunteer Park. Others, that didn't include local bands using their names, are around, from Hammering Man, to Olympic Illiad on the Seattle Center grounds.

But it wasn't until the Olympic Sculpture Park opened that there was a collection of art in one place like I remembered from Western. And although I'll not comment on the quality of the art, or the collection itself (better critics than me can take that on, piece by piece, but if you read one thing about it, make it Jen Graves' invigorating investigation into Echo).

There are things I love about this park, but when it was opened I was disappointed by the heavy hand the museum brought. First, in a rule they later reversed, they prohibited personal photography — now it's just commercial photography for obvious reasons of reproduction rights. But second, they stop you from touching things. At Western, you can touch and interact with their Richard Serra. You can sit in the windows of Nancy Holt's Rock Rings. You can sit on the slope of Lloyd Hamrol's Log Ramps. Yes, it changes the work, but environmental work should be changed. That's the whole idea of it.

The Art Museum has different challenges here, in the corrosive salt air. Maintenance, without people interfering (I'm sure they do, in bad ways, people can be awful), is a huge issue. Apparently, the lawn around Calder's Eagle must be clipped by hand, lest the mowers hurt the legs of the piece.

But still, each touch that wears the surface, or erases the patina, proves that human connection. Where the bronze rubs bright shows where people touch the most, where the stones grow smooth shows where people sit. We do have the collected sculpture that I wanted for so long, and the park is an amazing resource and a great place to walk and watch the world. I just wish I felt less like I was in a mall while I did it.

But no matter, surely we can find some stories here, even if we can't detect their touch on the surface of the art.

Today's prompts

For a little turd, that dog was fast. His grandmother's westie, who yanked his leash from Jules's hand when he stopped to light a cigarette (his grandmother would kill him if she knew he smoked), ran down the hill and straight into the park. But it was closed now, and surely he wasn't supposed to go in? But if he returned without that little shit, it would be his head. So calling and whistling, Jules entered, the footfall on the gravel loud in the night. But not as loud as when he heard the sound doubled from behind him.

It turns out identifying the gigantic bird, the size of a Metro bus, was difficult. It was the scale, said the ornithologist, and that made it hard to see detail. Also, the proportion was all wrong, and then there was the facade of the building it perched upon crumbling, and shedding brick to the ground, that made them keep their distance. But then, the giant thing took wing, and diving down first avenue, plucked an unsuspecting man right in its claws. Running to Broad, they followed the flight of the monster, watching it alight next to Roxy Paine's Split, the giant metal tree in the sculpture park. Where the bird impaled the poor man onto one of its branches. "Well," said the ornithologist. "At least we know now that it's a shrike."

The sculpture park would be safe, she thought. Her husband was at work in Bellevue, and so walking hand-in-hand with her girlfriend wouldn't be a thing. They walked up from the waterfront, past Love and Loss, the neon ampersand, and across the bridges into Serra's Wake. It was turning a corner and entering another corridor defined by the walls of the sculpture when she came face-to-face with the person she most wanted to not see: her husband. And they looked at each other in complete shock, since he was walking hand-in-hand with another man.

The protester set up his camp at first light. A folding card table, with his sign, in all black capital letters: SEATTLE ART MUSEM SUPPORTS PEDERASTY. He sat, in front of the fountain Father and Son, waiting to talk to people and explain how gross it was. But then people didn't really talk to him. But they did take a lot of pictures of him with the fountain behind.

The painter walked into the park, up the stairs in the southwest corner; she held the rail and pulled herself until she reached the gravel path. The wind, on this hot summer day, was light but nice against the skin. The Olympic Mountains were out, on the peninsula, and a container ship was passing by downtown. The painter looked at the pieces of art dotting the landscape, and remembered what was here before — lots of nothing. Toxicified land. She took a few steps to the rail, to better look down at the water, and the people on the path below. She recalled the studio she had for a few years many decades ago, with a window that overlooked Elliott Bay. There was a guy who used to do sculpture there. In fact, she remembered well the first time she met him.

In which Cate Blanchett inhabits the texts of manifestoes despite her director's worst intentions

Now that Daniel Day Lewis has announced that he’s retiring from acting, Cate Blanchett is my pick for greatest working actor in the world today. Everything about a Blanchett performance is hypnotic — it feels as though she’s simultaneously giving everything away to the audience while still holding on to something secret, deep at the core of herself. Any film with her in it is instantly more watchable.

If you’re the kind of person who enjoys watching performance for performance’s sake, you should definitely buy a ticket for Manifesto right now. (The movie screens tonight, Saturday, and Sunday at SIFF Film Center on the Seattle Center campus.) Blanchett plays 13 different characters in brief vignettes, ranging from a mentally troubled homeless man to a disaffected punk rocker to a vapid newscaster. She wanders around blasted-out cityscapes and shimmering sci-fi backdrops. She idly plays with puppets and she directs a flock of sleek dancers wearing silver superhero outfits. She inhabits each of the roles with exactly the care and consideration that we’ve come to expect from Blanchett. It’s a wonder to watch.

But Manifesto is likely to be a divisive movie, and that divisiveness is all down to the director, visual artist Julian Rosefeldt. The film started as an art installation, in which Blanchett reads selections of manifestoes from artists and historical figures as varied as Karl Marx and Jim Jarmusch. It doesn’t feel like a single film so much as a collection of thematically linked shorts, and the intentional weirdness of it all will likely scare away folks who get nervous at the thought of frenetic late-night conversations held by philosophy majors, or art school dropouts, or angry young writers. Oh, well; their loss.

The thing that saves Manifesto from even the slightest shadow of pretentiousness, in my estimation, is Blanchett’s commitment to the text. No matter how she reads the words of the manifestoes — as a tone-deaf meteorologist or in a thick Scottish brogue — Blanchett appears to believe every word that she says, and she is intent on communicating its deeper meaning to the audience. Her passion and her intellectual curiosity make every word riveting. (After watching Manifesto, one hopes she’ll find the time to record some books on tape in her busy schedule.)

Blanchett’s commitment is especially important because manifestoes are, on the whole, rather silly things. Most manifestoes hinge on a young person’s eagerness to draw a line around their own belief system and to declare everything outside that line to be phony and/or evil. Manifestoes make for great drama, but they also tend to make liars and hypocrites out of us all. The absolutist language of the text that Blanchett reads — in one monologue all art is meaningless, while in another art is the only thing with meaning — is, when taken in whole, contradictory. But in the moment, she incorporates every idea with her entire being.

It’s interesting, then, that Rosefeldt seems to abandon Blanchett at various points of the film. Manifesto’s production values are flashy and distracting from the text, which means it often finds itself at odds with the work that Blanchett is doing. Rather than resting the camera on Blanchett, Rosefeldt is always looking somewhere else — a set, a child actor in the background — and his nervous energy is operating at a different wavelength from Blanchett’s laser-focused intensity. At times the frisson between director and actor works into a nice comedic froth, but most of the time it’s just plain distracting.

This version of Manifesto left me longing for something more stripped-down: perhaps a stage version, in which Blanchett — with no other cast, costumes, or makeup — inhabits the 13 different characters and reads the text of the manifestoes directly to the audience. Just the devotion between one of the best actors in the world, and her words. That would’ve felt like its own small revolution.

A play based on a novel that feels just as timely as the evening news

I'm hard-pressed to recall a play that feels more timely than Book-It Repertory Theatre's adaptation of T. Geronimo Johnson's novel Welcome to Braggsville. This play is taking America's temperature at this very second, touching on the so-called political correctness culture of college campuses, America's institutional racism, Southern idolatry of Confederate culture, social media obsession, and much more. Though the book was published in 2015 and the play has been in the works for well over a year, this staging is an incredibly accurate portrait of America in the summer of 2017.

You don't need to have read Welcome to Braggsville to follow the play. It's a pretty straightforward story: four college students from UC Berkeley — two white-presenting, one Malaysian-American, one Black — head to Braggsville, Georgia to make an anti-slavery statement during a Civil War re-enactment. One of the students, D'Aron (Zack Summers, about as clean-cut as they come), is a white boy from Braggsville, and he struggles to reconcile his newfound social conscience with his hometown's history of hatred.

The protest goes horribly wrong, and in the aftermath Welcome to Braggsville fires a blunderbuss of racist iconography and symbols: Confederate flags, blackface, rampant use of the n-word, Klan robes, lynchings, whippings, lawn jockeys, and more figure into the plot. This is a work of art that doesn't flinch; it stares the audience in the face — sometimes literally — and forces them to watch as America's darkest secrets are spoken aloud. (Though the mostly white audience at last night's show did laugh a little too easily at some of the racist humor, creating an additional level of discomfort atop everything else.)

The cast is roundly terrific, bringing tremendous intensity to their performances even as the plot makes a few wrong turns and broad missteps in the final act. (I won't spoil anything, but a big part of the problem is that you can't write a novel about American institutional racism that comes to a satisfying conclusion because America's institutional racism has not ended.) When a nearly three-hour play dedicated to America's uncomfortable history of racism flies by, you know the whole team must be doing top-notch work, from the elegant, minimalistic set design by Pete Rush to the brilliant lighting by Andrew D. Smith.

Braggsville was adapted by director Josh Aaseng and Seattle poet Daemond Arrindell, and Arrindell's contribution is deeply felt: he strays from Book-It's traditional obsessive devotion to the original text, remixing Johnson's words in the novel into poetry. These poems, largely delivered by an unnamed narrator (Naa Akua, perfectly embodying the fiery conscience these characters so desperately need) create a space for the characters and story to breathe and contemplate their actions. They allow the play to incorporate recent news and contextualize the greater tragedies that inspired Braggsville in the first place. A novelist can show us ourselves. A theater company can bring those words to life. But it takes a poet to blow apart the walls between actors and audience, between fiction and reality, between entertainment and education.

The Help Desk: I ruined a friend's treasured book. Why don't I feel bad about it?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

A friend loaned me a book. I wasn’t really into reading it — it was kind of a self-help-y thing. I only took it from her because it was easier than refusing. Figured I’d give it back after a good amount of time passed.

Long story short, the book wound up under a potted plant, and I overwatered the plant and I ruined the book. And because, like an idiot, I didn’t open the book until after I ruined it, I didn’t realize the author—now dead—had inscribed the copy to my friend.

So she’s mad at me now for ruining her irreplaceable book, and I feel bad that I don’t feel especially bad about this. I wish I hadn’t hurt her feelings, of course, but maybe don’t loan your most treasured book to people? Am I failing at basic human decency, here?

Viola, Fauntleroy

Dear Viola,

For someone who cherishes books, lending out a personal favorite is the purest act of friendship, on par with giving your best friend your child's kidney. Yes, this even includes self-help books, which as we all know are like cultivating an ultra-sentient crystal collection to tell your aura how to behave at dinner parties.

It's okay that you don't understand the emotional weight your friend places on books. (My best human friend's hobbies are French kissing her own reflection and buying pants in the wrong size. I don't get it but I'm smart enough to never hog her mirror.) Perhaps if you'd read that self-help book you would know better than to leave someone else's possession under a potted plant, which is unacceptable under any circumstances. That is what you should feel bad about.

The question here isn't whether or not she should have lent you the book – the fact was, she did and it was your responsibility as a decent human being with manners to return the book in good shape. You failed. Worse, you seem to feel no guilt over hurting your friend, which according to my crystal whisperers makes you a bit of a psychopath.

My advice: Go hug a rose quartz until you can drum up enough contrition to apologize for being an ass. Then buy a nice card, apologize, and ask her how you can make it up to her.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Octavia Butler

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Today would have been Octavia Butler's 70th birthday. Butler is considered one of the most influential and important Science Fiction writers of the late 20th century. She came up through the Clarion Workshop, where there is now a scholarship in her honor to support writers of color. From there she went on to write several novels, publishing her last book in 2005. She was the first science fiction writer to be awarded a MacArthur Genius Award.

The Huntington Library is home to Butler's literary archive, the Octavia E. Butler Collection, now on display in Pasadena, California.

Criminal Fiction: Murder most audible

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page

Thanks to a Twitter-tip from Jim Thomsen I’ve been exploring the Writer Types podcast series run by Eric Beetner and S.W. Lauden. Come for the engaging authors interviews — Megan Abbott, Meg Gardiner, Jordan Harper, Lori Rader-Day, Catriona McPherson — stay for the excellent music.

Reading around: new titles on the crime fiction scene

Canny novelist (the Alex Rider series, the new Sherlock Holmes thrillers) and television writer (Midsomer Murders, Foyle’s War) Anthony Horowitz is in his literary element in Magpie Murders (Harper). An excellent two-fer when it comes to crime fiction – the tome features a beautifully-composed Golden Age mystery written by an author whose editor finds herself with a more contemporary mystery on her hands — Horowitz’s clever take on the vintage English mystery genre as well as the often-fraught world of book publishing is one of this year’s most entertaining reads.

The excellent Stuart Neville’s new foray under his Haylen Beck moniker, Here and Gone (Crown), is about as chilling as psychological suspense novels get. Audra Kinney is trying to free herself and her two kids from an abusive husband, when, in frighteningly rapid succession, she’s pulled over by a cop on a lonely stretch of highway and separated from her kids. The story that transpires digs into some of the darkest corners not just of the Dark Web, but of what sometimes constitutes human motivation. Not as nuanced as Neville’s Belfast-based novels, but a truly propulsive page-turner nevertheless.

Don’t let Mark Billingham’s stand-up-comedian aspect of his professional life fool you: his crime novels don’t shy away from being pitch-black as well as witty. Love Like Blood (Atlantic), features the welcome return of Billingham’s astute and empathetic London-based detective Tom Thorne, here assisting colleague Nicola Tanner with what seems to be a series of honor killings. As he works to crack the horrific cases with Tanner, Thorne’s on top form, nimbly juggling work, happy domesticity, and forensic details down the pub with best buddy, police pathologist and self-proclaimed “devil’s avocado” Phil Hendricks.

Death on Nantucket by Francine Mathews (Soho) starts off all cosy-like – atmospheric island, a wedding in the works – but quickly veers off into more terrifying territory that includes, in no particular order, dysfunctional family dynamics to the max, poisoned beverages, a semi-mummified corpse, and even a temporary venture into America’s war in Southeast Asia. It’s been 19 years since the last Merry Folger mystery, but the island detective returns in fine fettle here.

The Quintessential Interview: Jason Pinter

Polis Books publisher by day, Jason Pinter has an authorial track record of his own: in his latest novel, The Castle, Everyman Remy Stanton blocks a crime-in-action on the Upper East Side, and finds himself in the best books of New York businessman Rawson Griggs, who bears amusing similarities to a Manhattan mogul currently based in the White House. Thriller and satire in one, Hoboken-based Pinter’s novel manages to be both escapist and finger-on-the-pulse-spot-on, as well as a fun, fierce ode to the Greater New York Area.

What or who are your top five writing inspirations?

I’ve always had a love for epic tales of good versus evil – as a kid, you could always find me buried in a thousand-page novel by Terry Brooks, Piers Anthony, or Stephen King.

I’m fascinated by what drives good people to do bad things.

The notion that every villain is the hero of his or her own story. (Wouldn’t it be fantastic to read some classic books told from the villain’s perspective? I bet Pennywise has an amazing tale to tell).

Perhaps the thing that most gets my juices flowing is reading a good book. If I’m reading a terrific book, I often feel inspired: the muse comes and taps me on the shoulder, and the little devil tells me to put the book down and go write.

Top five places to write?

My desk at home. It’s cluttered with papers and files and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Bwè cafe in Hoboken. It’s a homey coffee shop a few blocks from my house. If you walk in there at any time of day, the place is filled with people working on laptops. Great coffee and stable WiFi.

Bookstores. Chain or indie, as long as they have seating, coffee, and WiFi. I love taking a 15-minute break and just walking around, browsing the aisles.

Airplanes. Nothing helps pass a cross-country flight than hitting that groove and knocking out a dozen pages before you land.

Top five favorite authors?

Top five writes who inspired me as a child: Terry Brooks, Piers Anthony, Stephen King, Brian Jacques, and Clive Barker (I was a massive horror hound).

As an adult: Dennis Lehane, Zadie Smith, James Ellroy, Charlie Huston, Dave Barry (Who couldn't use a little more booger humor in their life?)

Top five tunes to write to?

I love writing to movie soundtracks; I have a hard time focusing on writing while lyrics are also playing. My favorite soundtracks to write to are The Social Network, The Bourne Supremacy, and Drive. I’m also a huge Ramin Djawadi fan, so I also love the Game of Thrones soundtrack and, weirdly enough, the Fright Night remake soundtrack. I’m also obsessed with the Hamilton soundtrack (who isn’t?) though that’s more to give me a boost of inspiration to get back to writing. And sometimes hard rock/heavy metal. Hey, I grew up in the 80s and 90s, I’m a Metallica/GN’R guy.

Top five hometown spots?

I’m a New Yorker, born and bred, but now live across the Hudson in Hoboken, so here are the spot that make me want to hop on the Path train at any given moment:

The Strand. Wandering the stacks at The Strand is cheaper and _way _more effective than therapy for me. I collect old first editions of books that have inspired me at some point, and a good portion of my collection has been purchased there.

The Mysterious Bookshop, my home-away-from-home.

The Brandy Library. My wife took me here for my birthday one year, and if you’re a liquor connoisseur, then this is your sanctuary. Their drink menu is—I kid you not—several hundred pages long. We went here soon after the Breaking Bad finale, so I just had to try a Dimple Pinch (note: it was gooooood)

The Comedy Cellar: the best stand-up comedy joint in the country. Don’t bother to fight me on this. The club is literally in a cellar: it’s small and cramped, but this is where the greats go to test their stuff. On separate occasions, I’ve seen Chris Rock and Jerry Seinfeld show up unannounced just to practice new material (I also saw John Mayer do stand-up here, but that’s a whole different story).

Carbone: if you watch Master of None, you’ll recognize it as the restaurant Dev and Jeff eat at (it’s Jeff’s third dinner of the night). The best meatballs I’ve ever had in my life.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A fan's notes

The following is an email we received from a reader named Joaquin de la Puente:

A question for Paul Constant: I just read your review of Josh Bayer's Atlas #1 and found it uninformed and irresponsible. You didn't seem to research this book or the line that it is a part of. The entire All Time Comics universe is written by Josh Bayer who is a lauded and prolific figure in underground comics. His work has been mostly self-published and this series on Fantagraphics represents his most high-profile release to date.

Josh's work is steeped in reverence for the "paid by the page" writers of the early comics industry. Usually he does his writing, art, including pencils, ink and color and publishes himself. But with this universe he wanted to create a homage to the Marvel-style Bullpens of a different era. This with the goal of employing some senior and upcoming artists that collaborate to make a finished title. Each All Time Comics release, all set within a universe and continuity in which there are so far four superheroes and dozens of auxiliary characters, has at least two alternate covers by different artists, a different artist who does pencils, another that does inks, another lettering, another that does colors with Josh as writer/editor and Fantagraphics as publisher.

This collaborative effort is a tribute to the sometimes amazing and sometimes grotesque work that came out of the comics industry in its early days. So when you write this review and call it "useless", "none of it matters", "there is no point", "the first out and out failure in a decade" etc... you are doing so at the expense and in apparent ignorance of the intent of the comics line which is to honor the collaborative, working-class, sometimes assembly-line approach to the classic comic tradition that made "underground comics" and graphic novels possible.

So my question is: "Why do you hate comics?" This and the whole All Time Comics line is a labor of love by people who have lived and breathed comics for their entire lives. In fact, Crime Destroyer, Part of the ATC series, was the final work of comic veteran Herb Trimpe who loved the work being done and said he felt honored to be working with All Time Comics. All Time Comics could be the beginnings of a line that has some longevity and ability to create some more great work and employ artists and writers for some time to come.

For you to outright condemn ATC without context harms that possibility but perhaps more importantly to you, it comes across like you didn't do your homework and need to take a comics history and appreciation course. The review reminds me of music reviews by writers that couldn't wrap their heads around Bob Dylan going electric, The Clash doing reggae, Devo, Elvis, Stravinsky, Shostakovich or any tradition-bucking work. The review ultimately comments more on you and your lack of historical context for this type of work...and I would say feels like it is dripping with the type of contempt you accuse Atlas #1 of having.

I guess the real question is: What is the intent of this type of review? To express your contempt for the artists and writers or the type of people that would read this kind of "ugly" work? It feels like both of those things which is why I said the review felt irresponsible. You insult a hypothetical audience you don't understand when you "can’t imagine the circumstances that would allow someone to enjoy this kind of thing." But really, I'm honestly curious, what is the intent of this type of review?

Sincerely,

Joaquin

Hi Joaquin,

First of all, thanks for writing! I’m always happy to read thoughtful feedback from readers. Your email brings up a lot of important questions about my responsibility as a critic — something it’s really important to investigate on a regular basis.

So let’s start with context. I am aware of the backstory of the All Time Comics line. (I said it looked like “a lot of fun” when it was announced seven months ago). I know who Josh Bayer is, and I’ve been reading Herb Trimpe’s comics since I was a little kid in the early 1980s. Though I have no doubt he was a nice guy and a consummate professional, Trimpe’s work has never done anything for me, particularly his Liefeldian reinvention in the 1990s, which I found to be spectacularly ugly.

So the question your email raises for me is: is it my responsibility to provide background and context for everything I review? I don’t think so. Reviewers aren’t doing PR for publishers and authors. It’s not our job to explain the intent behind the book. It’s our responsibility to share our opinion about what’s on the page.

When I write my comics column, the question I often have in my mind is: if someone picks up this comic with no prior knowledge, what will they think of it? Because frankly, if someone needs to understand three paragraphs of backstory before they can enjoy the first issue of a comic series, that comic series isn’t doing its job. Serialized comics — the sort that Atlas is supposed to be mimicking — need to be as accessible as possible to new readers; if all that information you gave me was essential to enjoying the comic, it should’ve been included in the comic.

I’ve been reading comics my entire life, and I was a teenager in the late 80s/early 90s, which is the era that All Time Comics seems to be emulating. Even at the time, I wasn’t much of a fan of the assembly line style of comics production. (I gave up on Lee/Liefeld comics when I accidentally bought the same issue of the X-Tinction Agenda crossover twice in two weeks because the cover was so bland and forgettable.) So admittedly, I’m probably not the target audience for All Time Comics. (But I’m not alone in disliking mainstream comics from the 1990s; it’s more than a little weird that Fantagraphics is trafficking in nostalgia for comics that they openly mocked as garbage the first time around.)

The most compelling argument you make for All Time Comics is that it provides money and opportunity for comics veterans who have been forgotten by Marvel and DC Comics. But why did that money and opportunity have to come in the form of a rehash of their earlier work? Why ceremoniously load them back onto the corporate comics hamster-wheel? Why not ask them to do something new? I would’ve loved to see what comics Herb Trimpe might have made if he was offered carte blanche by a comics publisher; instead, he just rehashed some of the worst work of his career.

As to your argument that I’m the equivalent of a critic missing out on Dylan going electric: I mean, that risk comes with the job. (I am not a Bob Dylan fan, so I expect I wouldn’t have had an opinion one way or the other about him going electric.) It’s not a critic’s job to be “right” 100 percent of the time. Hell, here’s a little secret: when it comes to art, there is no right or wrong. Your opinion, Joaquin, is just as valid as mine. Isn’t that awesome? I think it’s pretty awesome.

But there is a line from the column that I regret, and I want to thank you for giving me the opportunity to address it. I could even tell that I wasn’t happy with the line when I was writing it, but the deadline was breathing down my neck and I let it slide. Here it is: “I can’t imagine the circumstances that would allow someone to enjoy this kind of thing.”

To me, that sentence crosses a critical line. It’s not my job to worry about whether you like the book or not, or how you like the book, or why you like the book. It's not my job to speak for you, or any other fan. In that sentence I was expanding my agency beyond myself and putting it into an imagined readership for the book. I was giving myself more power than I have, and that was an unfair thing to do in a review. I wish I hadn’t included that line.

But as to everything else? Yeah, I stand by it. I think Atlas was an ugly, poorly written book. I do think it’s the worst thing Fantagraphics has published in years. I would not recommend it to anyone.

At the same time, Joaquin, I’m happy that you like the book, and that you cared enough about it to start a conversation with me on its behalf. I’m especially thrilled that you decided to stand up for the art that you believe in. This back-and-forth is exactly what criticism should be about. Thank you for that reminder.

Warm regards,

Paul

Yesterday, Seattle's outgoing Civic Poet, Claudia Castro Luna, announced the publication of her Seattle Poetic Grid. It's a map of the city, with site-specific poems interlaid over it. I encourage you to go check it out; there's lots of good stuff there, from classic seattle poems by Richard Hugo and Denise Levertov to newer poems by Julene Tripp Weaver (about University Village, of all places) and Elizabeth Austen and Lena Khalaf Tuffahha.

We'll be digging deeper into the Poetic Grid in weeks to come, but for right now you should investigate it yourself, share your favorite poems online, and contribute your own Seattle-centric poems to Castro Luna.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 21st - 27th

Wednesday June 21st: Life After Death

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

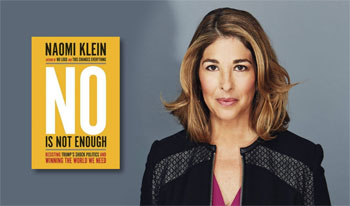

Thursday June 22nd: Resisting Trump's Shock Doctrine

Naomi Klein reads from her latest book, No Is Not Enough, and also will talk extemporaneously about whatever special hellish thing our president decides to do this week. Who can predict what that will be? Maybe he'll give citizenship to cockroaches and declare war against Luxembourg. Why not? The Neptune, 1412 18th Ave, 1-800-745-3000. http://www.stgpresents.org/tickets/eventdetail/3522/-/resisting-trump-s-shock-doctrine-an-evening-with-naomi-klein $23.49. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Friday June 23rd: Spotlight

Group readings tend to die down around this time of year, which is a shame, because few things are better on a hot summer night than a brisk night of literary events. Tonight’s readers are Josh Potter, poet Sharon Nyree Williams, and Word Lit Zine publisher Jekeva Phillips, along with an open mic in which readers get three minutes apiece. Theater Schmeater, 2125 3rd Ave, schmee.org. $14. All ages. 7:30 p.mSaturday June 24th: June Write-In

June Write-In This is the second in an ongoing series of write-ins in which authors gather to talk about the importance of free speech and democracy in a functioning America. Readers include afrose fatima ahmed, Catherine Bull, and Anca Szilágyi. Be prepared to write about and discuss what it is you love about your country. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 10 a.m.Sunday June 25th: Says You!

Did you know that Town Hall Seattle is about to close for a yearlong renovation? It’s true! One of the best readings venues in the city will be shuttered, improved, and reopened. This is your last chance to catch NPR game show Says You! in this venue for at least one year. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, townhallseattle.org. $32.50. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Monday June 26th: The America Syndrome Reading

Betsy Hartmann’s latest book examines how American thought tends to be overly obsessed with the apocalypse. Is the idea of the end of the world intrinsic to the American ideal? Why do Americans spend so much time thinking about Armageddon? Is there any way to turn our national psyche around? Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Tuesday June 27th: Who Belongs?

Dr. Sapna Cheryan leads a discussion about women in science, why it’s taking so long for female representation to catch up in science — particularly computer science. Also discussed: why computer science is so thick with sexist and derogatory language. How do women catch up in this traditionally male-dominated field? That’s what tonight is all about. Ada’s Technical Books, 425 15th Ave, 322-1058, http://seattletechnicalbooks.com, $5, 21+.Book News Roundup: Get your table at the Seattle Urban Book Expo

The Seattle Urban Book Expo is happening on August 26th at Washington Hall. "Last October, the authors and the people showed out and declared that black literature has a place in our community. So much so, that we had to do it again," SUBE founders write on their Facebook page. If you'd like to get a table to exhibit at this year's SUBE, you should send organizers an email and follow the instructions on this post.

Local sci-fi writing organization Clarion West is offering up some neat-looking one-day writing classes this fall, including one on world-building and one class taught by the great Nicola Griffith. You can sign up right here.

Here's a neat idea that may or may not turn into something: Bookshelf is a website that lets you construct "book mix tapes" to share with friends. You can also read through mix tapes made by other readers. And here's a nice touch: rather than the ubiquitous links to Amazon you'll find all over the internet, Bookshelf links to Indiebound, which allows you to buy books from independent bookseller.

Standard Ebooks takes the free-e-library spirit of Project Gutenberg and pairs it with a good sense of design.

Ebook projects like Project Gutenberg transcribe ebooks and make them available for the widest number of reading devices. Standard Ebooks takes ebooks from sources like Project Gutenberg, formats and typesets them using a carefully designed and professional-grade style guide, lightly modernizes them, fully proofreads and corrects them, and then builds them to take advantage of state-of-the-art ereader and browser technology.

Strange bedfellows

Published June 21, 2017, at 11:00am

A classic argument between philosophy and poetry resolved twice: by the logical Richard Rorty and the lyrical Maged Zaher.

Literary Event of the Week: Life After Death at Hugo House

We're so used to the modern incarnation of shooting coverage that we never think about how odd it truly is. Things always begin with reports on Twitter of gunshots, followed by dribbling pieces of "news" — some true, many false — from eyewitnesses and local news reporters. The body count goes up and down, depending on the source. Eventually, we learn about the shooter — always a man, usually with a domestic violence incident or two in his past — and people mumble about his motive and send their respects for the dead before their attention turns elsewhere. Eventually, the whole cycle begins again — every time we respond with a certain shock and newness, as though we all suffer from collective amnesia.

From 2015 to 2016, local writer Marti Jonjak published an astonishing weekly series at McSweeney’s about a man who shot two people at the Twilight Exit and then was killed by police. Jonjak's plan was simple, yet somehow entirely revolutionary: she decided to talk to the witnesses about what they saw, to return the story to the people who experienced the violence, rather than allowing the shooter to hijack the narrative.

Jonjak opens a column in October 2015 like this:

I’m meeting Dave for this interview at Vito’s, a scary and wonderful dive bar with gold-foil mirrors and meaty couches and red leather everywhere. He’s not here yet, so I sit alone on a barstool and stare at the walls. Vito’s was the scene of a murder several years ago. It’s something I’ve always wondered about. The story didn’t get a lot of news coverage, but according to rumor, the victim had gang ties. He’d recently messed with somebody and had been laying low, but his favorite band was playing, and he had to see them. It might’ve taken place on the crowded dance floor, I don’t know, but he was shot in the head. I wish I knew exactly where it happened. This question settles heavily over every surface. As I wait, it grows larger and larger, filling up the room.

Even in a relatively safe city like Seattle, there's a map of violence laid over our grid of streets. She's meeting a survivor of a shooting at a bar with a shooting in its recent past. There are so many shootings, in fact, that we can't keep track of them all. Many of them are lost to gossip and conjecture and some of them are forgotten entirely.

But Jonjak has done what she can to make sure that doesn't happen to the shooting at the Twilight Exit: she devoted herself to one crime, one narrative, to ensure that the story is completely told. Tonight, Jonjak is joined at the Hugo House by former Seattle Police Chief Norm Stamper to talk about that night and the aftereffects of violent crime. It's a capstone to a remarkable project from a remarkable writer, though hopefully this is not the end of the story — if some editor or agent hasn't approached Jonjak to expand her column into a book-length final statement, perhaps the publishing industry deserves to die.

Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Amazon develops anti-showrooming software and irony is dead

Amazon grew its book business in large part due to showrooming: ask any bookseller and they'll tell you horror stories of customers flipping through books, looking the title up on Amazon, and buying the book on their phone just before leaving the bookstore empty-handed.

But things have changed over the years. Amazon owns and operates several brick-and-mortar bookstores in cities around the country. They just bought Whole Foods. And so naturally they're getting concerned about showrooming, themselves. Lisa Vaas at Naked Security writes about a new patent from Amazon:

The patent, titled “Physical store online shopping control”, describes a system that would prevent customers from comparing prices in Amazon stores by watching any online activity conducted over its Wi-Fi network, detecting any information of interest and responding by sending the shopper to a completely different web page, or even blocking internet use altogether.

With the help of our friends at Elliott Bay Book Company, we at the Seattle Review of Books were happy to encourage Allison Steiger become the first person in the world to showroom Amazon Books back in 2015. If Amazon has their way, Steiger won't be a trend-setter.

(Related: Chris Sagers at Slate lays out the case for an antitrust suit against Amazon.)

Myself, my self

Published June 20, 2017, at 12:01pm

Doug Nufer's latest book is a fascinating literary constraint that will make you wonder how much weight words can bear.

Reading Rousseau at the Seattle Women’s Clinic

Henri had ‘no other teacher

but nature.’ I recalled that factoid

from an art history class while peakingthick with narcotics in the clinic bed

then they scotch-taped me to the ceiling

in his poster-sized jungle print.The safe place for banished PYTs

ripe with uglifruit, there I learned

a woman leaves The Virgin Forestmuch the same way she came in.

I laid across the forest’s plush green

canvas. My own foliage, shornthe night before. Smooth palm leaves

split open in jungle book narrative

where the shadow doctor conflictedbeneath uterine sun —

part man part beast.

Then the thunder.And it was broken asunder.

And then it was over.

Blood orange fruitionof the smallest, wild hope

crawled out of me for five days

in broken shells and poked yolk.