From constraint comes a new small poetry book

Sponsor Sagging Meniscus wants to make sure you've got this Thursday on your calendar: Seattle writer and poet Doug Nufer will be reading from his new book The Me Theme at Gallery 1412. More details, and a link to the event, on our sponsor's page.

You've seen Doug's name plenty of times on the site. He's a formal constraint-based writer, making some of the most interesting, and compelling, and challenging (in the best possible way) work. Take advantage of the opportunity to hear him read, accompanied by pianist Gust Burns.

Sponsors like Sagging Meniscus make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. We only have three openings left in our current block, all during July! Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

At Literary Hub, Stacie Williams writes about what it means to be a librarian:

In 1962, British librarian Douglas John Foskett wrote a paper titled The Creed of a Librarian: No Politics, No Religion, No Morals, in which he argued that “the librarian ought virtually vanish as an individual person, except in so far as his personality shed light on the working of the library.” Neutrality has been enforced from the top down, with our policymaking professional organizations, down to individual librarians in their repositories, as a way of shifting the responsibility of moral judgement from librarian to patron. For instance, neutrality says a patron who asks for help searching for romance books but says, “Don’t give me anything by a Mexican author,” isn’t to be questioned or challenged about a stance that may be prejudiced. Neutrality becomes a way to avoid questions or ethics that are wrong or make people uncomfortable. Article VII of the American Library Association’s Code of Ethics, amended in 2008 but first adopted in 1939, says “[W]e distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties and do not allow our personal beliefs to interfere with fair representation of the aims of our institutions or the provision of access to their information resources.”

At one of the bookstores I worked a very long time ago, a customer wanted to return a copy of Mein Kampf that he had bought from the store. When the bookseller asked why, the customer said that the edition had a foreword by a Jewish author placing the book in context and explaining why it should be read and not erased from history. The foreword, written by a Jewish author, rendered that edition of Mein Kampf "an inferior text," the customer argued, and he didn't want the book because it was "contaminated."

The bookseller, who happened to be Jewish, immediately backed away and refused to help the customer any further. She started crying and left the sales counter. Likewise, I refused to even talk to the customer, who then became agitated. Eventually, a manager stepped up and refunded the customer his cash, in an effort to get rid of him. It was a controversial decision — why should this awful human being get what he wanted, when we didn't guarantee any return? — and I still think about it often.

I am not a librarian and I have not attended librarian school. My only context for the questions raised in Williams's article is the above bookselling story and my experience as a journalist, and my opinion is this: objectivity is bullshit. Nothing human is apolitical, and to pretend otherwise is dangerously ignorant. (Note the repeated use of "he" in the Foskett quote above, which is a political decision that Foskett likely didn't realize was even a political decision.) I believe that it's better, in most instances, to acknowledge your politics, to be transparent about them, and to help the patron as best you can.

Williams draws a similar conclusion, but in a much more thoughtful way. I encourage you to read the piece.

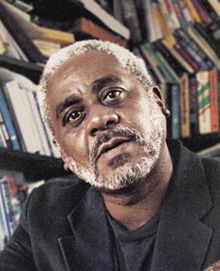

Talking with Charles Johnson about community, retirement, and writing a whole lot of books

Charles Johnson has been one of the most influential members of Seattle’s writing community. He’s contributed to the community in a number of ways — as a professor at the University of Washington, as a writer, as a friend to writers. Johnson recently joined the writing and literacy nonprofit Seattle 7 Writers, which donates to literacy organizations and donates books to readers around the region in shelters, detention centers, food banks, and other locations where people have need of good literature.

On Saturday, June 24th, Johnson will be headlining a fundraising brunch for Seattle 7 Writers at the Mount Baker Community Center. Every table at the brunch will feature one local writer, so attendees will get close personal contact with writers including David Schmader, Donna Miscolta, Claire Dederer, Claudia Rowe, and more. I talked with Johnson about the brunch and what he’s been working on lately. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Your Wikipedia page says you're retired, and I think you're maybe one of the hardest-working retired men I've seen.

Oh, that's why you retire from teaching, so you can get your art on your schedule 24-7. Artists never retire, but college professors do. That's true.

And how has your retirement been?

Well, it's been very good. I retired [from the University of Washington] in 2009, and I have been working steadily on all kinds of projects. I've published five books in the last two years, and I'm just putting together now the manuscript for next year, which is a collection of stories. It'll be my third short story collection.

My editor at Scribner just went over it. She didn't really have anything she had to do in the way of editorial work, but she just went over the stories and sent them to me. And so I'm going over her comments and putting together a proper manuscript to get to her next week. It'll be published next May. The title is Night Hawks.

All one word?

I'm breaking it up into two words, "Night Hawks." That's the title story, which is a story I wrote about my 15-year friendship here in Seattle with August Wilson. We had really great eight-to-ten-hour dinner conversations at the old Broadway Bar and Grill, which is gone now, on Capitol Hill.

In December you published a book about creativity and writing. And I wanted to ask if, at this point in your career, if you're sort of taking your teaching wisdom out into the world and teaching sort of in a more informal space?

Well, that's an interesting way to put it. The Way of the Writer evolved out of a longer book called The Words and Wisdom of Charles Johnson, which was a year-long interview that poet Ethelbert Miller did with me on every subject under the sun. He asked me 400 questions about everything, and I answered 218, and a lot of them were about the craft of writing, because he's a poet and also a teacher of creative writing.

And then we looked at that, and a couple of people commented, who had seen Words and Wisdom, that there was a book here that could be developed on the craft of writing. And I agreed. It was all there. I simply had to maybe revisit and update the essays that I did in response to those questions. And then I added a couple of essays that I had written on the craft of writing over the years.

So this book is essentially a record of my experience for 33 years as a teacher of literary fiction. That's about half my life, actually, 33 years.

But I still do teach. I'm going to work with people at the Spirit Rock People of Color Buddhist Conference in September. And I'm going to do two sessions with their teachers talking about the Buddha, Dharma, and how you can serve your communities with Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Buddhism has been an ongoing theme in your work. Has your teaching shifted over into a more spiritual place since you formally retired?

I've always been a very spiritual person. I've always been a Buddhist practitioner — my entire, really, adult life. I didn't bring that into the classroom with me; I would leave it outside the door. But I think it's pretty well known that I'm a Buddhist practitioner.

And so, people ask me questions about that and I'm happy to respond. It's all total, together, you know. Art is mind, body and spirit, and they all reinforce each other and serve the creative process, I think.

You recently joined the Seattle 7 Writers. Can you talk about what you like about them?

I joined on the invitation of Garth Stein. And I met Garth because every year we do the Bedtime Stories fundraiser for Humanities Washington, and he is the MC. I've written a story for them for every year for 18 years; it'll be 19 years this fall.

I've seen some of them and they’re wonderful. And you always seem so eager to be there.

Oh yeah. I think it’s a great experience. You create something new and it serves a good cause — the programs at Humanities Washington. And the new story collection coming out, Night Hawks, all of those stories except one were written for Bedtime Stories. Ten of the 11 were written for that.

And in my previous book, Dr. King's Refrigerator, five of those stories were written for Bedtime Stories. After I do them for the event and read it, my agent places it somewhere, and then very often it gets an award or it's reprinted or anthologized. So for me, the Bedtime Stories event is a perfect stimulus.

And with regard to the very, very good MC [Stein], he invited me to join the group because I think he's doing good things. The group is doing good things with writers and readers in Seattle.

And can you give us a little preview of what you're going to talk about at the brunch?

I want to talk to Garth a little bit before I actually do it, but my hunch is that what I'll do is I may read bit of something from the last book, The Way of the Writer, and then engage whoever is present in a kind of spirited Q and A about the creative writing process.

And there will be writers at every table of the brunch spread throughout the room, so that'll make an interesting forum to talk about writing.

Last March, I went to the Tucson Festival of Books. I was on a panel with Colson Whitehead, and then I was on a panel with my UW colleague David Shields, and another guy who wrote a book called Thrill Me.

But the morning before that afternoon panel, I spoke to writers about writing using The Way of the Writer as my springboard. It was just real. It's a roomful of writers because it's a literary festival, so I'm pretty familiar with that group — what kind of questions writers can ask. They ask the best kind of questions because they are immersed in the creative process themselves.

Lately I've been asking writers about community. Throughout your career, you've had a terrific commitment to community. You work with Humanities Washington, and you just joined Seattle 7 Writers, and you're very generous with your time. I was wondering if you think that a writer does have an obligation to a community — or does it depend on the writer?

I think you hit it when you said it depends on the writer. Some people are very eager to interact with other writers — to understand what they do, to do things with other writers that are for good causes. Like Humanities Washington, for example. I mean, I enjoy helping other writers, particularly younger ones, get published and get awards and colleagues.

I'm working right now with philosopher George Yancy on a book that he's going to do on Buddhism and whiteness, a critical race theory. I just alerted a lot of friends that I have in the Buddhist community, or the Sangha, to what George was doing. And maybe they'll make a contribution to it and make the book even richer.

I talk about that in The Way of the Writer, probably in the introduction. We don't live in isolation. I think we live in a world of interconnectedness with others. We might feel isolated sometimes; writing's a very lonely activity. You're doing this by yourself, usually, right? In a little room somewhere or, I don't know, wherever people write.

And you kind of forget that it takes a lot of people to get a book out there. The writer writes it, but then there's the editor who gives a good critical eye to something the writer might have missed. And there's the publisher, right? And then there's the bookstores. It really is a network, as Martin Luther King would say, a network of mutuality, that brings a book into being.

I've always been conscious of that, and grateful, too, and thankful for the people who enable a book to become a public object after it leaves the hands of the author. And maybe other writers don't feel that way, but I do think we're all conscious of the fact that we were given something by others, and it's very good, if we can, to give back.

The Sunday Post for June 18, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Nothing Tastes the Same

Friend of SRoB Rahawa Haile returns to the Appalachian Trail, this time on a road trip with her father. Speeding from BBQ to buffet, they take the first small steps toward knowing each other after a ten-year hiatus and map the distance that remains between.

Now, driving instead of hiking down these mountains, I learn that my father loves taking sharp turns too fast, something I never noticed growing up in the road-dull broadsheet that is Florida. I do not share his enthusiasm. I’ll take sore knees from 4,000-foot descents over feeling my inertia any day. I recognize for the first time just how much of him comes from the highlands of Eritrea. He's been courting death in this way since before I was born.

Also fascinating: the backstory of how the original article came to be, via an interview with Haile in the Columbia Journalism Review.

The art of writing an obituary

Meet Ann Wroe, obituarist for The Economist, who’s eulogized the lives of figures as towering as Fidel Castro and tiny as a fish (well, Benson was not so tiny, as fish go).

People think it’s a rather gloomy job, but it’s very seldom a sad job. Usually, the people you’re dealing with have lived for ages and have done really interesting things. It’s only when people die young that I think it becomes sad. I think of death as going into another place where you are as alive there as you are here. It doesn’t bother me at all.

A Look Back at Shel Silverstein’s Adults-Only Children’s Book

If you were born at a certain point in history, your childhood shelves included odd books about stunt-flying seagulls, sky-climbing caterpillars, and this gem: Shel Silverstein’s Uncle Shelby’s ABZ. I was lucky enough to read it (likely while sitting in the middle of the street with a handful of firecrackers) before the “adult only” flag was added to the cover. Kevin Litman-Navarro celebrates Uncle Shelby and the consternation of several generations of unsuspecting parents.

Given all of the thinly veiled adult humor throughout the book, it seems quite clear that Uncle Shelby’s ABZ Book is not intended for children. But some distracted adults, it seems, neglected to actually read it before passing it to their sweet, impressionable young ones — today’s parental equivalent of giving a child unprotected internet access. One scandalized reader on the book review site Goodreads didn’t realize her mistake until she had already begun a family reading. “The truly shocking page,” she wrote, “was where he was joking about going with kidnappers and eating the lollipops they offer.”

In Search of Fear

In its exclusive on Alex Honnold’s free-solo climb (no ropes, no company) of the massive El Capitan, National Geographic says Honnold’s “tolerance for scary situations is so remarkable” that he’s been a lab subject for neuroscientists fascinated by his ability to chill. Honnold’s take? “I just set [fear] aside and leave it be.” Philippe Petit, the man on the wire, has a somewhat more detailed and poetic anatomy of the deadly emotion.

A clever tool in the arsenal to destroy fear: if a nightmare taps you on the shoulder, do not turn around immediately expecting to be scared. Pause and expect more, exaggerate. Be ready to be very afraid, to scream in terror. The more delirious your expectation, the safer you will be when you see that reality is much less horrifying than what you had envisioned. Now turn around. See? It was not that bad.

Seattle Writing Prompts: Planes on Trains

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

The logistics of shipping and distribution of goods are amazing to think about. Even an ardent anti-capitalist has to admit that the ingenuity by which we distribute things around the world, even when they take tremendous resources, is impressive. Maybe I'm clouded by my love of trains, but rail is the mechanism that always invokes the most wonder in me. Ships are great, don't get me wrong, but heavy iron rolling on rails makes me feel like a kid when I watch them pass. Planes, too, because of the magic the demonstrate: for the natural engineer in all of us, trains and boats are more-or-less understandable, and the methods of their locomotion easily demonstrable. But planes rely on hidden physics, airflow over wings, incredible amounts of forward thrust, and a little white-knuckled hurling yourself into opaque clouds.

So imagine how exciting it is to see 737 bodies, not yet fully assembled, rolling by on trains through Seattle. They come from Kansas, where Boeing has a factory (unfortunately, to my point of view, who wished full assembly was done here in Washington even if it would negate the sight of the fuselages rolling through), and they are shipped north, then west, across Montana, Idaho, and Washington before crossing the Cascades near Everett and heading south through Seattle to Renton for final assembly.

I used to work at an office on the ground floor at the old Post-Intelligencer building on the waterfront, where the P-I globe is now. When a plane on a train went by, the view of the park would be eclipsed by this massive cargo — green, from the protective plastic wrapping, as if your new plane is the same as your new iPhone (if you love peeling the protective covering from a small thing, imagine doing it for a plane. I wonder how soon you'd learn to hate it, if it were your job?). Because I was obsessed, I'd run out on the balcony and take a picture as quickly as I could. I used to maintain a Twitter account to post those pictures, and then I assembled a photo essay when our offices moved from the building.

There's something about seeing a plane on a train that makes you appreciate the scale of trains themselves. They don't seem quite that big, until you see them carrying something that, in short order, will launch itself into the sky, clad in the livery of the final client. I want to see a model in a giant warehouse, with tiny trains traveling from Kansas to Seattle across America.

In Seattle, this common sight brings to light a number of interesting topics: Boeing, and its role in our local economy ("Will the Last Person Leaving SEATTLE — Turn Out the Lights"; Execs abandoning their Seattle, ostensibly due to traffic; factories moving around the country, and around the world), how trains run right through the heart of our city, and we can't really control what those trains carry past our doorstep, or how long they block traffic along the waterfront.

Not to mention how strangely hypnotic the sight is, standing on the bridge at Carkeek Park, or walking the waterfront, getting caught by the old Old Spaghetti Factory, seeing them roll past as you're caught going eastbound on Lander, watching planes roll by, green, with such a future.

Imagine now that you're trapped watching a train with five of them roll by. Imagine that each plane is destined for a future, and each plane will encounter thousands of people. That means that every train has a nearly limitless supply of stories. Let's find one for each plane.

Today's prompts

The first plane — This is the one that, after pulling into the factory, after being positioned in the assembly area, between shifts so that the riveting guns were silent — an employee inspecting the fuselage removed one of her ear protectors to scratch an itch and she heard an almost-silent mewing. And after yelling for her coworkers to shut up for a minute, discovered the kitten that had hitched a ride across America on a plane on a train.

The second plane — It's on this one, on an Alaska flight from Las Vegas to Montana, where a man who went in big and came away lacking is fretting over facing his wife to explain their diminished savings. He drank before boarding. He drank when, at altitude, first service came around. Then, with a bear-like howl, he cried out. People all around him looked as his large, 250-pound body collapsed on itself, sobbing, shaking. A small elderly woman, on her way to visit her wayward daughter, who was finding herself at a yoga retreat near Glacier, moved next to him, placed her tiny hand on his shoulder, and leaned in to speak the most calming words he'd ever heard.

The third plane — It's ten years into its service when this plane flies a seven-year-old who will become the President of the United States. It's the last time this child will fly with their father, who will die in the year following. It's notable because they're going to see Washington, DC, where the child's father hopes to instill a sense of purpose and pride in the child for their country, and where they will have a coincidental run-in, checking into the hotel, with a former congressperson that the child will never forget. And the flight is notable because, due to great irony, the man who runs against this child in the future (and loses, by a narrow margin), a teenager at this point, is sitting in first class, coming to spend Spring Break with his own professional lobbyist father, flying from the boarding school he hates so much.

The fourth plane — It's this one that comes closest to having an accident. It's an air traffic control issue, and the plane is saved by a quick-thinking pilot — who had once been a test pilot on the 737 line — who immediately responded to an impending collision light by pulling up hard and increasing thrust to jet the airplane to a much higher altitude. And in the bathroom, a woman applying makeup and nearly poking her eye out and dropping her little zip bag full of beauty kit everywhere, devises an idea for organizing her kit that ended up becoming a multi-million dollar business.

The fifth plane — This is the plane that the aliens take. It's flying to Bermuda, and then blink, it's gone. Nowhere on radar, and no wreckage ever found. It just disappears from the world. In fact, everybody aboard passed out, as if by magic, and awoke to the plane on stable ground, quiet, engines off. They woke, and looked around. A scream from the front of the plane, a man looking out the window. It was obvious on first glance, they were nowhere in the world. It was obvious on first glance that they had been abducted.

Is it just me, or has 2017 been a bad year for novels?

We’re not quite halfway through 2017 yet, but I’ve noticed a very visible pattern to my reading this year: I’m not enjoying novels the way that I always have. It’s been a while since I’ve read a novel that has really blown me away, the way memoirs from Patricia Highsmith and Sherman Alexie did this year. No novel has wowed me with its ingenuity and energy and passion, the way Claudia Rankine’s Citizen did. No novel has reached out and forced me to reconsider the world the way The Righteous Mind did.

The book-critic-o-sphere, even in its weakened state, has already promoted quite a few novels as the year’s best, of course. And if you’re preparing to counter this post with a tweet that reads “But, @paulconstant, did you read [insert hot 2017 novel title here]?” let me assure you that the odds are good that yes, I did try the book. I’ve abandoned more novels this year than at any other point in my reading life. I’ve tried almost every flavor-of-the-month and none of them have moved me.

I haven’t written reviews of these books or called them out on social media because, frankly, I’m not sure what the source of this problem might be. There are two options:

Maybe I’m not in a place to receive good fiction right now. This happens every so often, especially in politically difficult times. I couldn’t read fiction during the end days of the 2008 or 2012 elections, for example. So perhaps my adjustment into the Trump administration has temporarily eaten the part of my brain that enjoys novels. If so, I’m sure it’s a temporary condition and my fiction-brain will reaffirm itself eventually.

Perhaps we’re in a fallow period for modern literary fiction. It has been a while since some person or group of people has claimed a new literary aesthetic as their own. Not everyone is happy with these moments in literary history, but they at least provide a point of discussion for writers to consider as they move forward. As a young man, I was thrilled by the whole McSweeney’s aesthetic, which seemed to reinvigorate literature for younger audiences. I was less thrilled with the Tao Lin-style simple-prose aesthetic that made a big deal of ostentatiously incorporating tech brands like Gchat and Facebook into the narrative. But at least those writers offered critics something to align themselves against. You may not agree with a literary movement, but you can’t argue that literary movements allow literature the opportunity to reinvestigate what it has and has not been doing well.

Either of those statements may be true. Perhaps I’m too distracted by current events and addled by Twitter to focus on the quality literature that’s being published this year. Or perhaps we’re in a too-comfortable fallow period of the kind that has traditionally preceded some young writer’s attempt to blow the whole damn kingdom up in order to reinvent it.

Either way, I can’t wait until I’m eagerly engaging with literature again; this last half-year has been difficult, because while non-fiction might help me understand the world and poetry might help me see the world, I build my world out of fiction. A good novel rebuilds your understanding of the universe from start to finish, and I have rarely lived in a universe more in need of reinvention than this universe we’re living in right now.

The Help Desk is on vacation (again)

Cienna Madrid is, despite what some of her friends and family might tell you, a human being. Human beings take vacation in the summer. There will be no new advice column this week, because Cienna Madrid is on vacation.

If you want Cienna Madrid to stop taking vacations, you should email her your best literary etiquette questions. If you keep her engaged and entertained with your emails, she will never leave us again. That address is advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Portrait Gallery: Sharma Shields

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday June 15th: Writers & Poets of Washington State

Western Washington poets Gary Lilley and Ann Tweedy team up with Spokane story author Erin Pringle and Spokane novelist Sharma Shields to bridge the divide and bring eastern and western Washington together at last. For one night, let’s pretend the mountain range, desert, and broken political discourse that separates us just doesn’t exist.

Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, hugohouse.org. . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Future Alternative Past: Dead(ish)

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Live long and prosper

Last night I dreamed, prosaically, that I was conversing with my oldest niece. My half-sobs kept trembling up to disturb the surface of our conversation; I excused myself to her by saying how much she looked like her mother, my baby sister, dead now four years. Then I woke, realizing that the face and voice I’d been talking with didn’t merely resemble my sister’s, they were my sister’s, back when she was young, vibrant, beautiful, cancer-free. Alive.

So there you have two forms of immortality: survival via remembrance and via genetic legacy. But this has never been enough for the bulk of us. Like religion, SFFH has sought for centuries to address that lack. Beginning with Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein, continuing through George Eliot’s 1859 novella “The Lifted Veil” and beyond, the fantastic genres have consistently questioned the supposed impenetrability of the barrier between life and death. Which you would naturally expect from ghostly tales of haunted mirrors and clairvoyant ascetics and so forth, but sometimes science and technology get dragged into the fray.

“Corpsicles,” as they’re facetiously referred to, are one example of sfnal immortality made (perhaps prematurely) real. The thought is that frozen people — whole bodies, or, less expensively, just their heads — will be thawed and restored to life decades after they’ve died. Though Walt Disney was an early supporter of human cryogenics, he didn’t get himself frozen, (let alone become the first corpsicle, as is often rumored). That honor goes to Dr. James Bedford, whose body, after his death in 1967, was cooled to a temperature of minus 79 centigrade and is now stored at Alcor Life Extension's Arizona facilities.

The answers to moral, technical, and other questions rising from the practice of cryogenic suspension — Would revived corpsicles have legal rights? What would motivate their resuscitation? Who could be held responsible in the case of accidental thawing? — are explored by quite a few SFFH authors. In addition to those listed in the linked articles I recommend Tanith Lee’s novelette “The Thaw.”

Another favorite sfnal way to cheat death is to upload one’s memories and/or consciousness into another living being’s brain or, more typically, into a computer. In Octavia E. Butler’s Wild Seed, her villain Imaro does the first at will; he couldn’t care less that his head-hopping dislodges and kills a body’s original tenant. James Patrick Kelly’s “Think Like a Dinosaur” examines a problem that develops when transferring consciousness to artificially created bodies. William Gibson and most cyberpunk authors opt for the machine upload scenario, and of course ethical quandaries can be involved there as well, as readers of my Making Amends series (“The Mighty Phin” et al.) are aware.

The aforementioned Gibson famously said: “The future is already here — it's just not very evenly distributed.” Which may well be the truth when it comes to a third form of sfnal immortality: medical advances. Already we have a sharp disparity in average life expectancies due to the availability of insurance and the quality of care afforded the rich as opposed to the poor. Already we have toilets that monitor urine flow and analyze hormone secretion. Bruce Sterling’s 1996 novel Holy Fire) extrapolates these points out to a time when his protagonist shops for an affordable, reliable life extension treatment. Never mind the excruciating pain she must subject herself to — this is a largely financial decision. Also one on which market forces, planned and unplanned obsolescence, and general demographics come to bear.

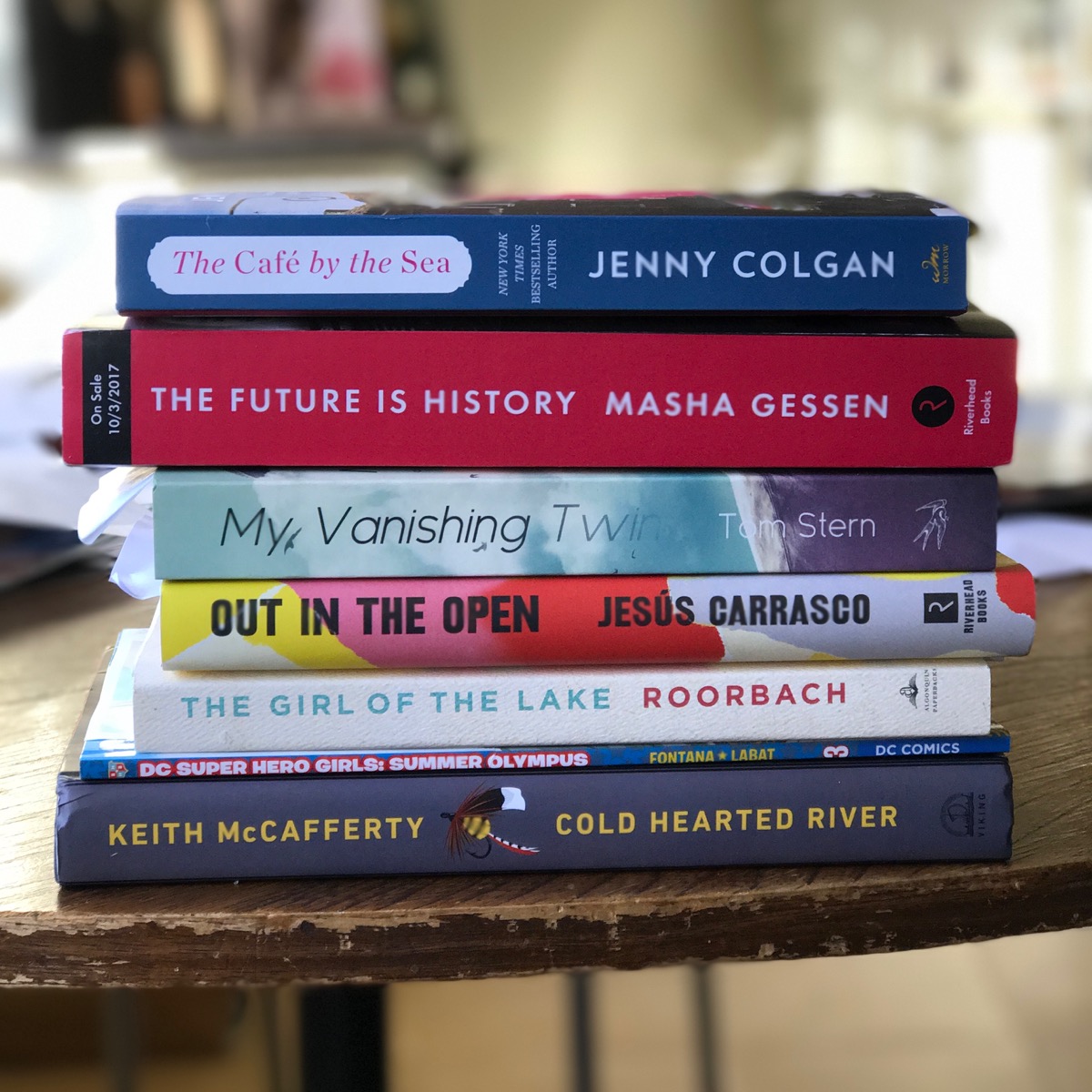

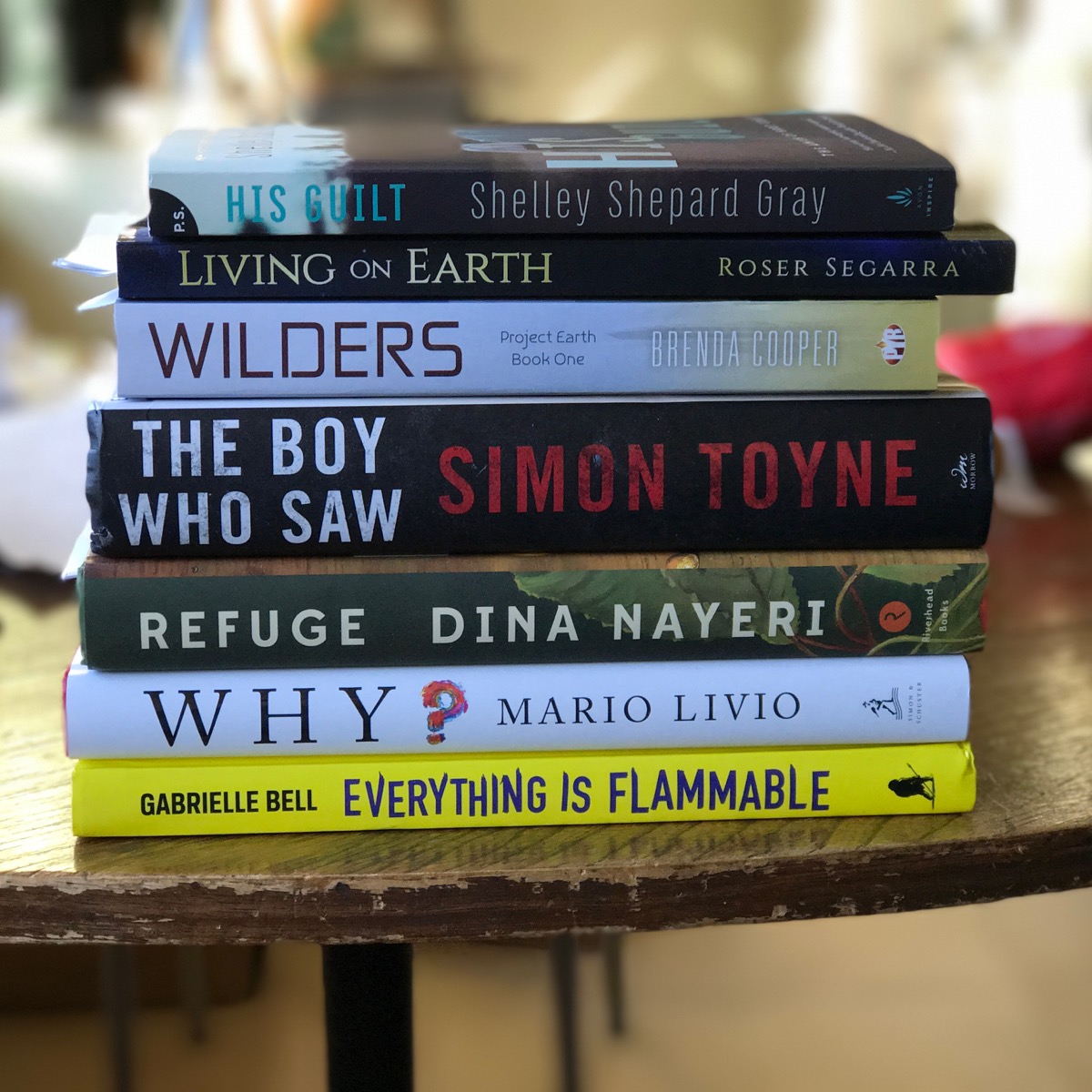

Recent books recently read

Despite In Search of Lost Time’s (Aqueduct) omnipresent cancer treatment medtech, this standalone novella resonates less with the hard science stylings of cryogenics, uploads, and gene-tailoring than it does with the happily-ever-after limbo at the end of fairytales. Author Karen Heuler’s heroine Hildy discovers that chemo infusions targeting malignant lesions on her “tempora” — an imaginary area of the brain — allow her to see, manipulate, and ultimately steal other people’s time. Her superpowers neither free nor cure Hildy, though. Instead, she struggles to integrate them into a humane and principled philosophy while fending off the self-interested alliances of warring would-be time-mongers. She girds herself for battle in red-heeled boots, silk head scarves, and penciled-on eyebrows, but kindness and self-reflection prove to be her most kickass weapons.

Firebrand (Tor Teen) is A.J. Hartley’s second novel set in Bar-Selehm, a gritty, steampunk analogue of South Africa. Steeplejack introduced readers to Anglet Sutonga, who began the book as an impoverished young laborer among Bar-Selehm’s chimneyed rooftops and ended it hired by her government’s main opposition party as a spy. Now Sutonga, member of a racial minority distinct from the region’s ruling whites and indigenous blacks, becomes entangled in a plot involving smuggled war refugees and stolen blueprints for a deadly machine gun. With her usual flair for leaping headfirst into trouble and sorting out the consequences later, she takes on a psychopathic assassin, a supernatural legend come to haunting life, and a hate-spewing white supremacist in her pursuit of truth and at least an approximation of justice. The results satisfied both my cautious mind and my crusading heart.

Seattle-area Futurist Brenda Cooper’s Wilders (Pyr) is the first volume in her new Project Earth series. The premise is promising: megacities house most of North America’s population, with the surrounding land slated for “re-wilding,” a sort of remediation-cum-restoration project. Our entry point into this near-future scenario, though, is the somewhat feckless Coryn Williams, whose older sister Lou strikes out on her own as soon as she can to do cool stuff like reintroduce wolves to the prairie. Coryn, abandoned, must stay a couple of years after that in the milieu that mysteriously led their parents to kill themselves — there’s a paragraph on possible reasons for their suicide on page 196, but by then Coryn has achieved adulthood and set off with her robot companion to track Lou down. Revolt among non-city dwellers and deception among city rulers make for a gloriously unpredictable denouement and hold out hope for more action in the rest of the series.

Couple of upcoming cons

Westercon is your prototypical large regional science fiction convention. Past iterations — all taking place, per the organization’s website, “west of the 104th meridian” — have featured art shows, filking (fannish folk music), and everything else con-goers have come to expect from full-service conventions. This is its 70th year of meeting those expectations.

But wait — do you like SFFH books more than the genre’s movies, cosplay, games, and such? Then Readercon is your cup of vodka. Two tracks of panels talking about books and one room of dealers selling them. That’s it for programming. Authors are the only Guests of Honor — two living and one dead per year — plus a plethora of guests of no particular honor but plenty of literary distinction, like Samuel R. Delany, Kit Reed, and Jonathan Lethem.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A womb with a view

Tomorrow, Tatiana Gill will release her new comic Wombgenda at the Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery as part of the Comics & Medicine Conference. Over the last couple of years, Gill has become one of Seattle's best, and most prolific, autobiographical cartoonists, and Wombgenda collects some of her latest work — most of it related to women's health, but with some current events mixed in.

The three long pieces in Wombgenda address Gill's journey to developing a positive body image, her abortion story, and an account of getting a new IUD at Country Doctor. Her style in these strips is very reminiscent of Seattle cartoonist Roberta Gregory's autobiographical comics from the 1990s — simple figures, little to no backgrounds, and a lot of words packed into every panel. They feel something like handwritten letters from a friend — confessional, intimate, exuberant, and heartfelt.

Most of Gill's stories are about discovery: learning she's not alone, figuring out what to do to solve a problem, looking into the basic day-to-day processes of a doctor who specializes in women's health. If you are a woman wrestling with body image issues, or unwanted pregnancy, or other health issues and these comics land in your hands at just the right moment, they could easily be the most important comics you'll ever read in your life. If you are not any of those things, Gill's specificity — her confident voice and strident curiosity — can help put a face on an issue in a way that might change your perspective. And isn't that what non-fiction comics are all about?

The other material in Wombgenda mostly hews to political spot illustrations drawn from the tradition of American World War II propaganda posters. (I like the one of Lady Justice and Lady Liberty flipping a rich guy's chair over with the caption "Let's work together and overthrow the patriarchy.") She also includes a page of love notes to cartoonist women from Seattle who influenced her, giving the comic the air of a 1990s fanzine.

Maybe one day, Gill will get a fancy book deal from a big New York publisher to do a graphic memoir and she'll disappear for a few years while she works on her magnum opus. But for now, we're lucky to have her out in the streets of Seattle, attending our protests, telling the stories of women, capturing everyday life in a city that's always changing. She's telling this city's stories, and we're lucky to have her.

In the recording studio with Sherman Alexie

It’s a cold and rainy March morning in Pioneer Square, and two men in a dark suite at Clatter & Din recording studios are chasing after a ghost. In the next room over, Sherman Alexie is reading his memoir, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, into a very expensive microphone. He’s recording the audio version of Love, which is set to be released in June, but the ghost hunt is getting in the way.

Here’s the problem: the director of the audio book, Jeremy Wesley, claims he can hear a high-pitched whine that piggybacks onto every word Alexie says into the microphone. He asks the audio engineer, Brian Sloss, if he can hear it. They ask Alexie to say a few words. Sloss first says he can’t hear the whine — it’s indistinct, Wesley says, just a bit of frizz hiding behind each word — but then, after a moment or so, he picks it up. “Yeah,” Sloss says. “Yeah, there it is.”

“We’ve got bad luck with the gear,” Wesley says. “Yesterday we had two cords go down. This is a bad way to start the day — it throws people off.” The two men start fiddling with the wires connecting to their elaborate computer setup, trying to determine the source of the ghostly whine. They get more flummoxed with every passing second. (For the record: my decidedly untrained ears can’t hear a goddamned thing, and in fact I thought Wesley was joking when he first started talking about the noise.)

For about 15 minutes, the hunt goes on as Sloss and Wesley float and discard a series of theories. Then they start replacing cables. Sloss goes into Alexie’s recording room down the hall, disconnects the cables connecting to the mic, and installs a fresh set. A moment or two later, Wesley and Sloss are sitting, expectantly, in their studio, waiting for Alexie to read. Their frustration is visible in their tense backs and jaws. When Alexie’s words come over the speakers in the studio, the two men relax as though they’re stepping into a sauna. The ghost haunting the words — wherever it came from — is gone, and recording can ensue.

Wesley has done a lot of work with audio books; he directed the audio version of Lindy West’s memoir Shrill, too. What does an audio book director do? Mostly, Wesley says, he listens to ensure that the author is “talking into the mic correctly, that we get the recording, and that it saves properly.” As Alexie reads his book aloud, Wesley reads along on a manuscript loaded onto his iPad. Whenever Alexie pops a “p” sound into the microphone, pauses too long between words, or flubs a pronunciation, Wesley makes a notation on his manuscript, reminding him to fix the error in production.

Alexie is one of the most talented readers on the planet, so Wesley says he’s got a pretty easy job of it this time. Yesterday, he recalls, Alexie “busted it out so quickly that we got even more done than we intended. We have the studio for four days, but he might finish it in three” because he’s such a professional in the recording studio. It helps that the book is of such high quality; Wesley praises the “caliber” of the work. “It’s just good,” he enthuses. The way he says “good” makes it sound like a word he cautiously preserves behind glass, only breaking it out when absolutely necessary.

During a break in the reading, Alexie invites me into the recording booth to look around. It’s dark inside, with no windows out into the studio to see Sloss and Wesley. Alexie’s recorded other audio books at Clatter & Din in studios that have a more traditional setup, with a line of sight between the reader and the engineers. Which does he prefer? Alexie looks around the booth, which is a little bigger than a closet. He says this works for him — especially given his memoir’s subject matter.

“It’s like a confessional” in the booth, he says. This way, when he reads, “I can imagine my audience. Sometimes I’m talking to directly to my mother. Sometimes, my wife and my kids.”

I step into the booth, and take another step, and then the silence subsumes me. It’s almost physical, this silence: you’re dipped into it, like caramel, and the whole world disappears and is replaced by the absence of sound. I blurt out a “holy fuck” at the unexpected vacuum, and Alexie nods. He recognizes that look of mild panic and wonderment on my face. When he’s in the booth, he says, “it sounds like I’m actually beside myself.”

The break ends and Alexie gets shut into the soundless room. Back in the studio, his voice sounds so clear in the speakers that he might as well be sitting there with us. He reads for a few minutes, and then Wesley makes a note on his iPad and steps on a pedal which puts his voice in the headphones Alexie is wearing in the booth.

Wesley asks Alexie, “could we do this one more time? You missed [the words] ‘dirty shirts.’” Alexie reads the passage again, inserting “dirty shirts” into the right space. He keeps moving forward through the text.

He reads a sentence and pauses, reads it again: “’Not even though I’ve been heavily marked by their scent?’ Did I write that sentence? That’s an awkward construction.” His voice pauses over the speaker, and then pops back in, with an audible shrug. “Wouldn’t be the first time,” he says.

Unlike most authors reading their own work for the audio book, Alexie is writing and rewriting parts of Love in the booth as he reads it aloud. With less than three months to go until publication date, Alexie says he wrote seven new chapters of Love while in the booth yesterday. “They’re short chapters,” he tells me. “The longest one is like four pages.” Wesley interrupts with a correction: “I think it was like eleven chapters.”

As he reads, poems burst out of him and demand to be added to the manuscript. Alexie sends me a photograph of one poem he wrote on both sides of an index card during a recording session:

At one point, Alexie starts making more mistakes: “I can’t get that rhythm right,” he says, saying one sentence over and over again. He reads the word “interviews” instead of “intervals.” He can’t land the phrase “when he was drunk.” He stumbles on the word “anesthetized.” He inserts the word “mom” when the text says “mother.”

Finally, Alexie realizes, “I’m not looking forward to reading the rest so I’m psychologically sabotaging myself.” He slows down a little bit and trudges forward until he gets to the passage he was avoiding — a youthful confrontation with his mother, when he returns to his room and sulks and punches the ceiling knowing she’s directly above him. After that, it’s back to normal. He relaxes and sinks into the words and makes fewer mistakes and embraces the text, and is embraced by it.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 14th - 20th

Wednesday June 14th: You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me Reading

Sherman Alexie is Seattle’s most entertaining reader, the most famous literary figure from Seattle, and one of our finest writers. And tonight he’s launching the biggest book of his career — a memoir about his complicated relationship with his mother. This reading is sold out, but Town Hall often has standby tickets available at the door. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://www.townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Thursday June 15th: Writers & Poets of Washington State

Western Washington poets Gary Lilley and Ann Tweedy team up with Spokane story author Erin Pringle and Spokane novelist Sharma Shields to bridge the divide and bring eastern and western Washington together at last. For one night, let’s pretend the mountain range, desert, and broken political discourse that separates us just doesn’t exist. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://www.hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday June 16th: Wombgenda Launch Party

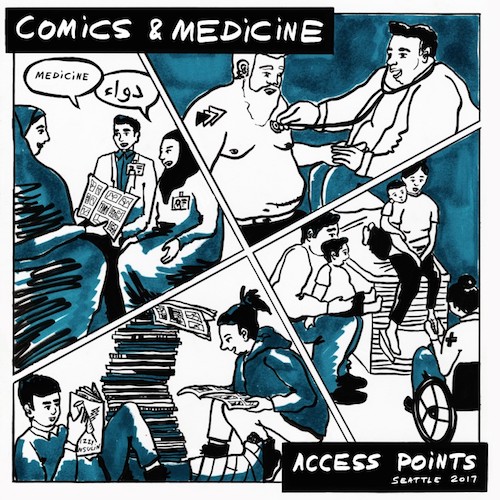

Over the last couple of years, Seattle Weekly contributor Tatiana Gill has become one of the city’s best and most reliable autobiographical cartoonists. Tonight, she debuts a new collection of comics specifically related to health issues, as part of the weekend-long Comics & Medicine Conference that’s visiting Seattle. Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore. Free. All ages. 6 p.m.Saturday June 17th: Comics & Medicine Conference

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Various locations, http://www.graphicmedicine.org/2017-seattle-conference/.Sunday June 18th: Thick as Thieves 2 Launch Party

The vacuum left behind by the passing of free comics newspaper Intruder was quickly filled by Thick as Thieves, a new anthology of Seattle cartoonists. Tonight, the second issue of Thick as Thieves launches with music by freaky screamy rock demigods HHRRIISSTT, a Mario Kart 64 tournament, comics art, and a big-ass raffle. Fred Wildlife Refuge, 128 Belmont Ave. E., 322-7030, http://www.hugohouse.org. Free. 21+. 7:30 p.m.

Monday June 19th: Discovering Seattle's Parks Reading

Did you know that there are 426 parks in Seattle? Linnea Westerlind has visited every single one of them, and now she’s turned her blog about visiting them all, YearofSeattleParks.com, into a fully fleshed-out book about those pockets of green which make our city so damn livable. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Tuesday June 20th: Afterparty Reading

Set in a near(-ish) future in which anyone can print drugs at home, Afterparty is about a designer drug that becomes the basis for a new religion. After the religion starts, people begin to die. Author Daryl Gregory will discuss whether or not Afterparty was inspired through pharmaceutical intervention tonight. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Literary Event of the Week: The Comics & Medicine Conference comes to Seattle

Seattle is an international hub of the global and public health communities. Seattle also has one of the mightiest comics scenes in the country. In almost any other year, if you were to sketch out a Venn diagram of those two communities — medicine and comics — there would be very little overlap. But this year, Seattle is host to the eighth annual Comics & Medicine Conference, an international celebration of the communication of medical issues in cartoon narrative form.

The conference brings together academics, health care professionals, and artists into a thematic weekend of programming (this year’s theme is “Access Points”). I talked with Comics & Medicine co-founder MK Czerwiec about why she believes health care and comics go so well together.

“Comics have the power to convey important information in ways that people who are dealing with issues in health care and caregiving find appealing to absorb,” Czerwiec explains. Comics have been used in public health situations for decades to make information accessible in ways that can “transcend language barriers,” but they also provide patients with a “form of reflection and ... storytelling” that can help in the healing process, and they help others empathize with patients. For those reasons, she says, nursing and medical schools are beginning to use comics to teach students.

Czerwiec says that Seattle has existed on this intersection between comics and medicine for a very long time. Cartoonist Mita Mahato, who has helped to organize this year’s Comics & Medicine conference, has long been a booster. Ellen Forney’s memoir about life as an artist with bipolar disorder, Marbles, has fast become a classic in mental health circles. And “of course, Meredith Li-Vollmer at the King County Public Health Department has come to our conferences in the past and presented projects that she's done with David Lasky in the public health arena.” Li-Vollmer and Lasky worked on the comic No Ordinary Flu, which saw a print run of over half a million copies translated into a dozen languages distributed around the country.

Registration for the conference is packed full, but the weekend is studded with a number of free events that are open to the public on a first-come, first-served basis. Seattle-area autobiographical cartoonist Tatiana Gill will be launching a health-related comic called Wombgenda at Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery in Georgetown on Friday night, and the downtown Seattle Public Library is hosting public events all weekend long. Topics in the open sessions include discussions of displaced communities; a talk by Seattle’s Erma Blood, the pseudonymous organizer behind the anti-sexual-assault comics site Grab Back Comics; and a series of quick talks on exploring disability through comics.

And of course, now that the Senate is deliberating on a health care bill that could gut Obamacare by forcing 24 million Americans off health insurance, this year’s theme of “Access Points” is particularly meaningful. Access is more important than ever, Czerwiec explains, and the question of who gets what care is a central issue of our time.

But she’s quick to point out that you don’t have to be a cartoonist or a PhD to attend Comics & Medicine’s free programming. ”I think anyone who has an interest in stories and health care” could find something of value, she says. Ultimately, the conference is devoted to consideration of “how we think about health care,“ with the hope of reimagining it and rebuilding it “in ways that are empowering to all of us as patients and caregivers and providers.” Comics are the great equalizer.

Stitch by stitch by broken stitch

Published June 13, 2017, at 12:01pm

When the world tries to kill Sherman Alexie, he just gets bigger and better.

Book News Roundup: Stacey Levine, William Shakespeare, and James Baldwin

- Brooklyn Rail published a great interview with Seattle's own Stacey Levine:

I see novel-writing as an opportunity to ask dozens of questions. The question of self-“realization” is going to be among them, but I like to think a novel is a chance to throw dice that ask combinations of even broader questions. “What is the experience of being alone versus being ‘beside’ somebody else?” And smaller ones: “What is the best way to describe that one sensation?” And situational questions, too: “What would this character do if she were trapped in a well and mocked by local teenagers?”

The Sherman Alexie media blitz continues, with this great New York Times profile of the author. (Any piece that says Alexie could pass for "the world’s warmest don" is a winner.) Alexie's memoir You Don't Have to Say You Love Me is available for sale today. We'll have much more to say about it on this site — [winks at reader] — very soon.

Literary Hub took a brief tour of James Baldwin's FBI file. Their fear, distrust, and hatred of Baldwin is a testament to the power of writing. He was more powerful than the FBI, in the end.

Did you know that there's a podcast where LeVar Burton reads a short piece of fiction to you? How have you not already subscribed to this one?

Adrea Piazza reports on an interesting new independent bookselling model at the New Yorker:

The C.S.A. model is simple: consumers commit a certain amount of money to a farm up front in exchange for a portion of the future harvest. Farmers use the resources to support themselves during the slower months. Over the past few decades, C.S.A.s have grown in popularity across the United States. Many farms on the Blue Hill peninsula have adopted such programs, and Haskell watched a local brewery, Strong Brewing Company, get its operation off the ground with a community-supported beer program. “The idea of purchasing a season’s or a year’s worth of books seemed like an interesting way to structure thinking about a customer’s relationship to the store,” Haskell said recently. At Blue Hill Books, C.S.B. members can purchase a “share” for a thousand dollars—or partial shares for two hundred or five hundred dollars—and draw on that credit to buy books throughout the year. “It’s not a donation; it’s not an investment,” Sichterman explained. It’s more of a “gift certificate for yourself.”

- Weirdly, Quartz has published the best take on that whole Trump/Julius Caesar flap that happened over the weekend. (Side note: remember when last weekend didn't feel like a million years ago? Remember when the first five months of a presidency didn't feel like a decade?)

Summer of Boys

In the beginning, it was innocent. Just play. Let’s mess with Mrs. Flowers’ mailbox! Fisher and Price asked me to spy on an old witch they believed lived alone in the woods. Is her husband dead? Or does she just hate men? I wondered. I wondered if she would ever come out of her shack. They tried everything to catch a glimpse of her. Sometimes they fisted worms and mud inside the black hole of it, then pushed the hard red flag up in high salute. Special delivery. Sometimes they didn’t erect it at all. Instead I took long walks with those two leading me through the woods in the heavy heat of curiosities. We built camps. We arranged rocks. We smoked cigarette butts. We lit twigs on fire. We lit trash on fire. We broke brown beer bottles against old trees. We pretended to be married. In a navy blue cotton shirt with a loose ruffle along the bottom edge, I was the bride, marching toward them. In the warm August air, my veil lifted off so easily.

Modern life, guided by a set of tested principles

Sponsor Lori Tsugawa Whaley, a third-generation Japanese American, was raised in a primarily Caucasian community and felt disconnected from her Japanese heritage. While exploring this ancient culture, she discovered a source of truth — the code of ethics known as bushido. Bushido means “the way of the warrior”; it is the set of chivalrous principles that governed the behavior of the ancient Japanese warriors known as samurai.

Lori Tsugawa Whaley brings these concepts to everyday life, showing through examples the kind of ethical and moral choices you can make when guided by principles. As she says, "I believe you were born to live a life of courage, honor, and integrity." Read an excerpt on our sponsor's page.

Sponsors like Lori make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us as well? Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. We only have four openings left in our current block! Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

This morning, the folks at Seattle's own Gramma Press announced that they'll be releasing a new book from poet Anastacia-Reneé (who we published back when she was known as Anastacia Renée Tolbert) on July 1st. The collection, titled (v.), is described this way:

Using a reimagined alphabet, Anastacia-Reneé sets about taking on everything from love to cancer, monsters, growing up, growing into our bodies, and the ways in which even our bodies are not our own. Her words define and redefine, explore hidden truths and expose the lies we are raised with.

This is a big release for Seattle publishing, and we can't wait to see it. You can pre-order (v.) from Gramma directly, or you can pre-order it from your local independent bookstore.

"I didn't set out to do it, but what I had done was I made a comic": Talking with MK Czerwiec, cofounder of the Comics and Medicine Conference

This weekend, the eighth annual Comics & Medicine Conference will take place in Seattle. Registration is full, but the conference also hosts a number of programs at the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library that are free and open to the public. The conference is bringing local and international cartoonists together to discuss the many ways that narrative comics about medicine can inform, entertain, and inspire the general public. Last week, I talked on the phone with MK Czerwiec, a co-founder of the conference, about how she came to comics as a medical professional, and why she believes that health care is everyone's business. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Why comics and medicine? What makes those two things a good fit?

There are a lot of wonderful answers to that question, which is why we love having annual conferences — because people come from all over the world to tell us their answer. In general, it seems that comics have the power to convey important information in ways that people who are dealing with issues in health care and caregiving find appealing to absorb.

One example of how comics are used in medicine and why comics and health care go together is that there's a long history of public health messaging through comics because they're accessible. They can potentially transcend language barriers — the visual appeal. They can take a lot of information and make it kind of quick and well-organized.

It’s also a great patient education tool, but what we found too is that it's an incredibly powerful tool for patients to use as a form of reflection and for storytelling about their experiences of illness. And then it's an incredibly powerful experience to bear witness to those experiences and kind of have that empathy connection.

And comics are being used to teach in medical schools and nursing schools and across many different areas of education — in and outside of health care.

And how did you come to health care storytelling through comics?

I came to it really out of necessity. I was working as a nurse at the height of the AIDS crisis in Chicago, and I would come home and I just felt this huge chasm between my everyday life and my work life. I was having a lot of trouble making a bridge between those two things. And I also was really having a hard time processing all of these intense sufferings, experiences, and these lives that were kind of coming to an end before me.

I had tried [writing those experiences through] text alone and that worked a little bit — like keeping a journal. I sometimes had occasionally tried images alone — making memorial paintings and painting screens in memory of people who I cared about, just sort of the symbolic language to remind me of things that were important to me about them. And then, it got to a point where, after doing this for five or six years, each of those individual methods were failing.

It came down to one day when I had to figure out how to get all of that out of my head. When I showed up at work, my patients deserved for me to be present to them, not my own suffering. I sat down with a blank piece of paper and I drew just this picture of myself and wrote above it, "I feel miserable." And then I put a box around it, and then I put another box, and then I just found myself combining image and text in this sequential fashion.

And I didn't set out to do it, but what I had done was I made a comic. And the thing that was really surprising to me was that I found myself in a completely different place than when I started. Something about the process of making that comic was transformative for me. And I just kept using that as a tool, as a nurse, to cope with what I was bearing witness to, and I found that it was really helpful.

And when did your experiments become more formal?

I ended up going into the field of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, in part because I really wanted to study why it is that certain ways of telling stories can be so helpful to us when it comes to illness. And I wanted to inform my comics, because I continued to make comics, and I knew I wanted to continue to do that.

But I wanted them to be better, and I wanted to inform them with a lot of theory and thinking about story and illness and health care. When I was working as a nurse, I was doing comics as a way of being present to the now and being able to be there for my patients. When I went into the academic side and started looking at this with a critical eye, that was when I started thinking about all the possible applications.

And then, I came across a book while I was doing my Master's studies called Mom's Cancer, by Brian Fies. And it changed my way of thinking. I just thought, "Wow.”

I got in touch through the internet with a few people who were starting to think along the same lines. And that's where we are today.

That was around a time when comics were coming to be more accepted in academia generally. Did you get a lot of pushback when you were trying to put comics and medicine together?

No. Quite the opposite. I could tell that I was in a really supportive environment at Northwestern, where some of the people around me saw the potential even more than I do. They were very encouraging to pursue it and pursue it thoughtfully. I've actually been surprised how embraced we've been. The Journal of Internal Medicine now has a graphic medicine page, and that really blows my mind because that's such a traditional medical journal.

Seattle has a huge global health and public health community here — we have PATH and the Gates Foundation and all that. And we also have a strong comics community as well. Is that why you chose Seattle for this conference? Or was it just our time? Or did you throw a dart at a map?

No, all that was absolutely a part of it. We had been hearing from some great Seattle creators, Mita Mahato being one of them. She’s our on-the-ground organizer [for the Seattle conference] who's, of course, a PhD literature scholar who has used comics in her teaching and really got invested in graphic medicine. But then at the same time, she is just an astonishingly talented papercut artist and comics creator in working on her own narratives, and she's been really active in the community.

And of course Meredith Li-Vollmer at the Seattle King County Public Health Department has come to our conferences in the past and presented projects that she's done with David Lasky in the public health arena. And Ellen Forney has been a keynote for us. We had so many people we knew in Seattle. When a couple of them said, "we think that we could get the support here to do this," we were really excited.

The registration is sold out, but you have a lot of free and open components to the conference. Do you have any advice for somebody who is thinking about attending some of the free programming? Do you need to be a medical professional to get a lot out of this?

I think anyone who has an interest in stories and health care and the ways in which we could approach how we think about health care differently would get a lot out of this. I think they will be really excited about what's happening in the graphic medicine community.

The title of my graphic memoir that just came out recently is Taking Turns, and what that title refers to is this idea that we really all are people taking turns being sick, and the divide between provider and patient is an artificial one — a necessary one, but an artificial one — and I think that it's important to remember that we all have a stake in this. Not just providers, not just caregivers, but all of us. And so I absolutely think that the public is welcome, and I don't think there's any kind of information anyone would need to know about graphic medicine before they come.

All of our keynote addresses are open to the public, and a number of the sessions. I think people will be really excited about this just right off the street.

Do you find yourself focusing any more on the political side of health care because of the AHCA and Obamacare?

We absolutely focus on it. We chose the theme of “Access Points” [for this year's conference] partly to think about some of those things. Who gets care? Who gets what kind of care? And how is that changing in this current climate? The threat to that access is more acute than ever.

I like to think that graphic medicine draws on the deep traditions of comics as both coming from the underground and bearing witness to stigmatized truth, but also the political tradition. The long tradition of political comics is alive and well. And access to health care, and comics about access to health care, are a big part of that.