Thursday Comics Hangover: Out of left field

Yesterday, I was planning to pick up the first issue of Secret Empire, the new Marvel Comics crossover. (Technically, it was issue #0; the first issue of Secret Empire — as in the issue marked "#1" — is due on May 3rd. If you're already confused, I apologize for what I'm about to put you through.) Every once in a while I like a big superhero crossover if it's handled well, and I enjoyed Nick Spencer's run on Ant-Man a while ago. Seemed worth a shot. But then I saw this tweet by Marvel editor Tom Brevoort:

A quick semi-word of warning for this week's books: the three Opening Salvo issues are meant to be read before Secret Empire #0.

— Tom Brevoort (@TomBrevoort) April 18, 2017

And because of that tweet, I didn't bother to pick up Secret Empire #0. If the first issue — sorry, the zero issue — of a series requires a "semi-word of warning" that three other books should be read beforehand, I can't really be bothered.

Look, I appreciate that superhero comics are a serialized storytelling medium. The minute a story has a conclusive ending, there's no reason for readers to pick up the next installment. But I do expect a story to make sense in and of itself, with a beginning, a middle, and some semblance of an ending. If the beginning of a book requires advance reading, it's not really a beginning.

Or let me use another example from a different publisher. I found the first collected volume of Detective Comics from DC's Rebirth line, Rise of the Batmen, to be a lot of fun. It's basically a Batman superhero team book, in which Batman must assemble a team including the formerly villainous Clayface and three interesting female characters from other Batman-themed books — Batwoman, Spoiler, and the Orphan (who used to be Batgirl) — to fend off an insidious Batman-themed threat.

Rise of the Batmen is mostly a good example of serialized superhero comics done right. The bad guys have a clear motivation, the heroes all have distinct personalities, and it's all terrifically, deliciously silly. Sure, it's a bit too goth — it is a Batman comic, after all — but it's brisk and entertaining and it never takes itself too seriously.

But then comes the ending. One of the characters supposedly dies. But then a page or two later we find out this character — gasp — didn't die after all! Par for the course for superhero comics. Except the character didn't die because they were plucked from the death scene by someone in another dimension or something, a bad guy who had nothing to do with the rest of the book.

Presumably, this plot device is setting up a crossover in some other, future DC Comic further down the line. But if you're reading this book as a book — which is to say you're expecting it to have a beginning, a middle, and an end — you're going to be incredibly disappointed. This isn't a fair ending. It's not a surprise, or a twist. A reader couldn't be expected to know what the hell is going on here without reading a ton of other comics. It's not even a deus ex machina; it's a non sequitur.

I love the fact that superhero comics never end, but I hate the fact that superhero comics are now absurdist echoes of themselves. Comics in the 60s and 70s and 80s used to catch readers up and explain the intricate mythologies behind the characters along the way. I understand that fashions change, and that the exposition-heavy comics from decades ago now read as impossibly clunky.

But surely there must be some way to convey the dense mythology of superhero comics gracefully? One thing comics are great at is broadcasting a lot of information in a relatively small amount of space. Modern superhero comics are all about withholding information, and demanding that the reader invest in dozens of books in order to understand what's going on. This philosophy is not only anti-new-reader; it's anti-comics.

The populist who crashed the party

“I apologize for standing up so high,” Thomas Frank announced from behind the podium at Town Hall Seattle last night. He observed that the audience members who gathered by the stage to ask him questions were forced to gaze up at him, as though he was a wizened old man sitting at the peak of a mountain. “It's not very populist of me,” he joked.

In reality, Frank couldn’t be any more populist if he discussed his new-in-paperback book Listen, Liberal while sitting in the middle of the audience in the pews of Town Hall. Frank addressed income inequality and the Democratic Party establishment’s dismissal of the working class with a single-minded intensity.

Frank railed on the current system, in which a few elites in the top ten percent enjoy a booming economy while everyone else in America lives in a state of perpetual recession. He says that since roughly the 1980s, America has offered its citizens economic “growth that doesn't grow and prosperity that doesn't prosper.”

Frank places the majority of the blame on the professional class of experts who run the Democratic Party. He said they refuse to crack down on their peers in the banking, pharmaceutical, and real estate businesses who are looting the American people for all they’re worth. This is because, he said, Democrats have come to believe in a “meritocracy” where “everyone gets what they deserve and what they deserve is directly tied to how they did in school.” If you didn’t go to a good school, or if you chose the wrong (read: non-STEM) major, Frank said, the creative class — and there Frank paused to reflect on the absurdity of “the idea that creativity is the property of a class” — believes you deserve the misfortune that you somehow delivered onto yourself.

Meanwhile, the pundits on every channel declare that “the answer to every question every time is to move to the center,” when in fact the problem is clear: “the party of the left isn't interested in its historical mission,” Frank said. That mission? To stand up for the working class. Donald Trump proved himself during the 2016 election to be “a hypocrite, a vulgarian, and a bigot,” Frank said, but he admitted that Trump recognized the unrest unfolding in middle America. The sorrows that Trump highlighted during the campaign, Frank said with a tone of astonishment in his voice — “those are things my people used to say.”

And because Trump continually discussed a problem that Democrats refused to even acknowledge, the Democratic Party is now at its lowest ebb “since 1920.” Frank told the audience that the only way to interpret the 2016 results is “a wipeout for the Democratic Party,” which he accused of “militant complacency.”

By design, Frank didn’t focus much on solutions to the problem. He was in full-on accusatory mode, identifying the systemic rot in America’s economy and the Democratic Party, though toward the end of his lecture he rattled off a few policies Democrats should support, including free or affordable secondary education and laws that promote unionization. The solutions aren’t the hard part, Frank said. On the contrary, “it takes ten seconds to come up with winning issues.” The problem, he warned, is that the Democratic Party is “going to have to be dragged kicking and screaming to victory.”

Bill O'Reilly is out at Fox News. What about his career as a bestselling writer?

Good news! Now that all the allegations against Bill O'Reilly have finally gotten public attention, Fox News has kicked the man to the curb, canceling his O'Reilly Factor TV show. It's embarrassing that it took this long, but it's good to see that activism eventually pays off.

However. O'Reilly is also a bestselling writer — or more likely, "writer" — of historical books. His books warp and twist history into something that is barely recognizeable, but they sell like the proverbial hotcakes.

Even worse, O'Reilly right now has a children's book at the top of the bestseller charts. Co-"authored" with bestselling hit factory James Patterson, Give Please a Chance is an etiquette book for children:

Of course, every angry white grandpa in America who is continually enraged by "PC Culture" is now going to buy a copy of this book and mail it to their grandkids out of spite. We can't do anything about those horrible people. But will publishers think twice about their relationship with O'Reilly?

It's doubtful. As the disastrous Simon & Schuster deal with Milo Yiannopoulos proves, corporate publishers will cling to potentially moneymaking authors until the very last possible second. Some truly despicable comments by Yiannopoulos had to come to light (and had to spread widely) before they reversed their decision to publish his memoir. It seems doubtful that Henry Holt, the publisher of O'Reilly's work for adults, or Little, Brown, the publisher of his books for kids, will cancel the titles or sever their relationship with him.

But O'Reilly's TV show wouldn't have been pulled if people hadn't put pressure on O'Reilly Factor advertisers. Allegations about O'Reilly had been circulating for years; it wasn't until people stood up to say "enough" that Fox News took notice. So maybe it's worthwhile to let Henry Holt and Little, Brown know how you feel about their profiting from a man who even Fox News won't touch? Do their employees care that they're promoting the work of an alleged sexual predator? Maybe ask Little, Brown and Henry Holt those questions on Twitter and send them some emails and see what kind of a response you get.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from April 19th - April 25th

Wednesday April 19th: The Book of Joan Reading

Portland novelist Lidia Yuknavitch is a Northwest superstar. Her prickly, gorgeous fiction is at recognizable and more than a little bit scary. (It’s scary in part because it is so recognizable.) Yuknavitch’s latest, The Book of Joan, is a sci-fi novel that retells the story of Joan of Arc in a blasted-out dystopic wasteland. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday April 20th: Dock Street Salon

Phinney Books’s Dock Street Salon series is always a fun time. Authors talk in a fairly up close and intimate setting with an engaged and excited audience. Today’s readers are Anne Liu Kellor, Jennifer D. Munro, and Ann Teplick. Expect a reading, a lively Q&A, and maybe some booze (not in that order.) Phinney Books, 7405 Greenwood Ave. N., 297-2665, http://phinneybooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Friday April 21st: The Histories Reading

A few local writers have told me that Seattle poet Jason Whitmarsh’s second book, The Histories, is their favorite poetry collection this year. It’s a book of absurdist, deeply funny prose poems that constructs an alternate history for the world, with singing Kafkas and MacGyver references galore. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St., 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Saturday April 22nd: Water & Salt Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Sunday April 23rd: Caucasians Anonymous Reading

You might know Marcus Harrison Green best for his excellent news site, the South Seattle Emerald. But tonight, he’s showing off a new side: he’s debuting a reading of his work-in progress play titled Caucasians Anonymous, which investigates “the social construction known as Whiteness.” This event also features a Q&A on race and privilege. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Monday April 24th: Breaking the Bond Reading

The very fine Texas playwright Rupert Reyes brings a staged reading from his latest work-in-progress play, Breaking the Bond, to the U District’s own Jack Straw Gallery. Featuring local Spanish-speaking readers, this play discusses topics of deportation, anchor babies, and national identity. (Reyes has also acted in the film Office Space.) Jack Straw Gallery, 4261 Roosevelt Way N.E., 634-0919, http://jackstraw.org . Free. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Tuesday April 25th: Till Tonight

New local writing residency Till brings a little bit of a writing residency to you with this special writers’ night out. Show up with your favored writing implement (although please recall that typewriters are really annoying in public places) and share some space with other people trying to get words down on paper. Speckled & Drake, 1355 E. Olive Way., (917) 476-932, http://tillwriters.org/. Free. 21+. 6 p.m.Event of the Week: Lena Khalaf Tuffaha at Elliott Bay Book Company

It is probably no mistake that some of the best poets are translators. While translating poetry from one language into another is an impossible, thankless task — I’ve heard it described as performing open heart surgery with a chainsaw — it still teaches you to ask all the right questions.

Why did the poet use this word in that particular spot? Does a line break mean the same in this language as it does in the original language? Just because you’ve managed to assemble a word-for-word translation of a sentence, the rhythm of the translated sentence might be completely wrong — a sentence can sound like a crashing wave in one language and a galloping horse with a trick knee in another. Those airy, complicated questions of translation are bound to make anyone a better writer.

Redmond writer Lena Khalaf Tuffaha has translated other poets from Arabic to English. She’s written beautifully about the experience in an essay on her site titled “Translation as Poetry.” She explains that the “first time I unlocked one of these phrases on my own, I felt like I had put on goggles and was happily diving into the cerulean deep of a pool after years of blurry immersion.”

Now, Tuffaha is publishing her first book of poems with prestigious Pasadena publisher Red Hen Press. Water & Salt is a book that spans the globe, from Seattle to Jordan and back again:

We are driving away

because we can leave

on the magic carpet of our navy blue

US passports that carry us

to safety and no bomb drills

to the place where the planes are made

and the place where the president

will make the call to send the planes

into my storybook childhood

The repetition of the “planes,” there, from being manufactured to being launched, is a meaningful one. Here, in Seattle — once the Jet City, though that name has fallen into disfavor in the age of Amazon — the planes are a point of pride. They represent jobs and industry and security for families. There, they bring endings to childhood.

These poems bounce back and forth between worlds to look at familiar objects from both sides. Tuffaha compares vivid street markets to fluorescent supermarkets. She writes, “I love to tell you where I am from,” when she says “the nine letters” — Palestine, the “place with a name charged as an electric fence” — that inspire opinions in absolutely everyone. Her poems are addressed to ugly Americans and friends and Syrians and her close family. Even Tuffaha’s beloved coffee habit is different in America (“free-trade shade-grown organic”) than it is in the Middle East (“…never serve coffee without ground cardamom.”) The sun casts different shadows here and there. Everything looks a little different.

It becomes obvious as you read Water & Salt that Tuffaha is still deeply invested in the business of translation. Not even something as innocuous as an almond can just be itself. Here, they are dried and brown and vacuum sealed. There they are green and so sour they’re “puckering.” Her poetry is always translating something — experiences, cultures, memories — for someone else. She’s a patient intermediary, explaining how one word can have a million different meanings. It’s all a matter of perspective.

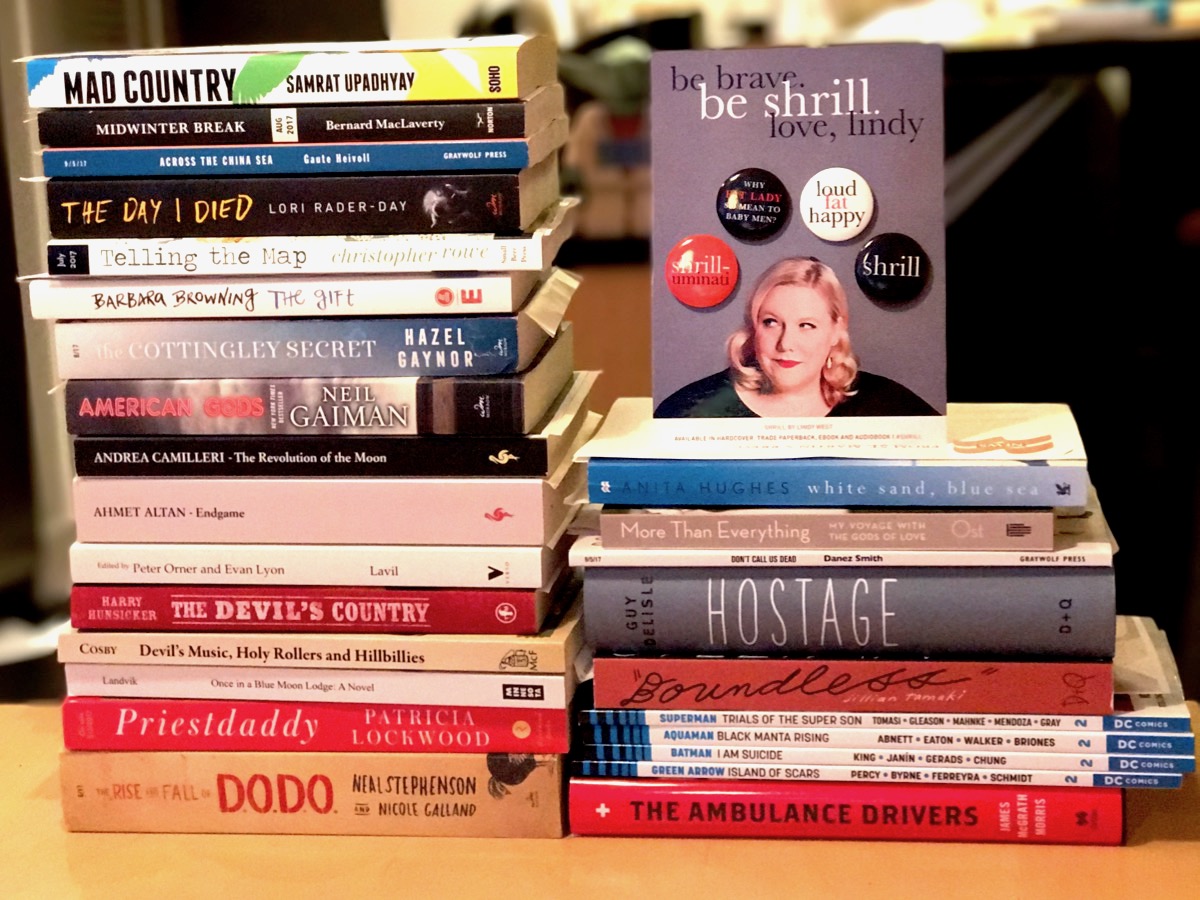

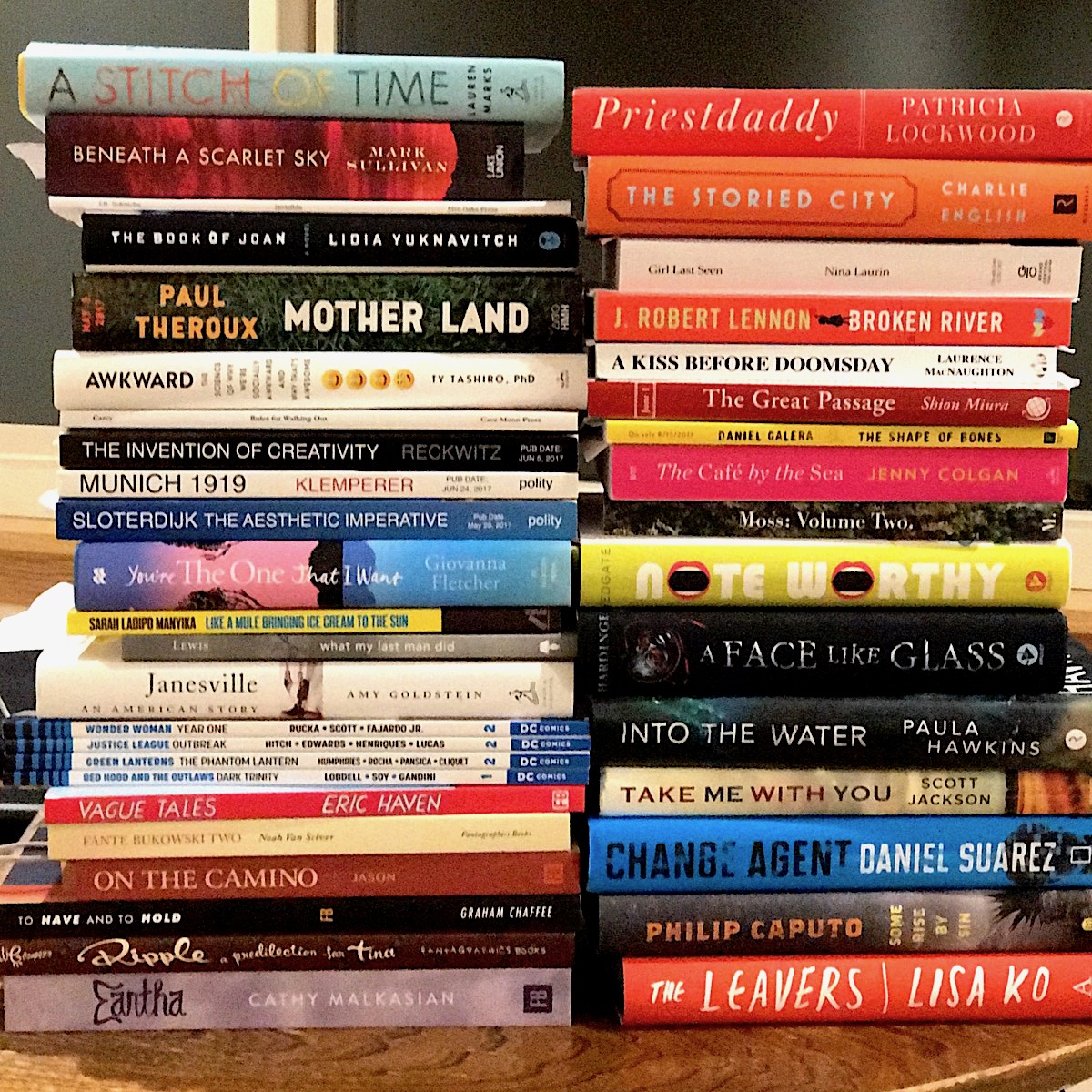

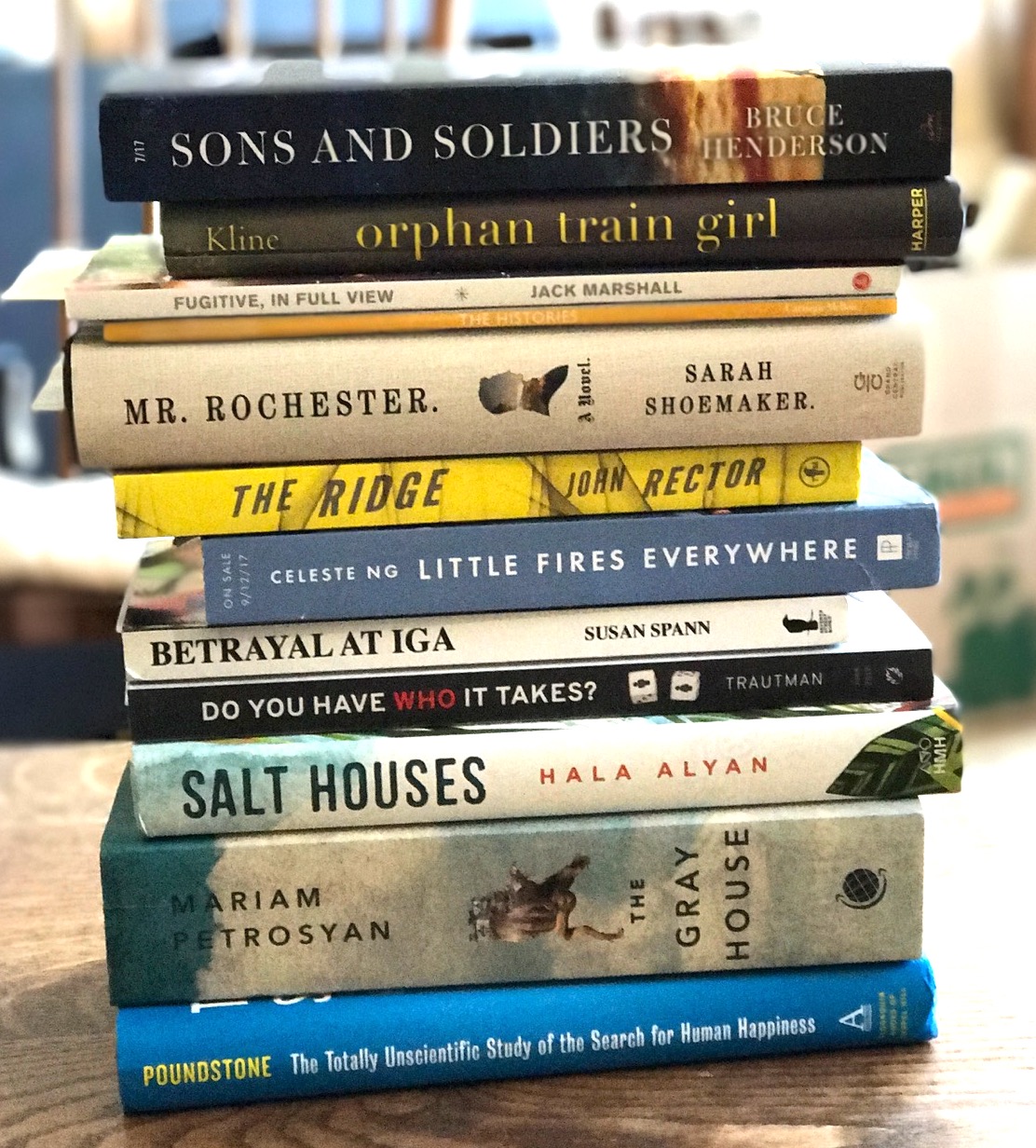

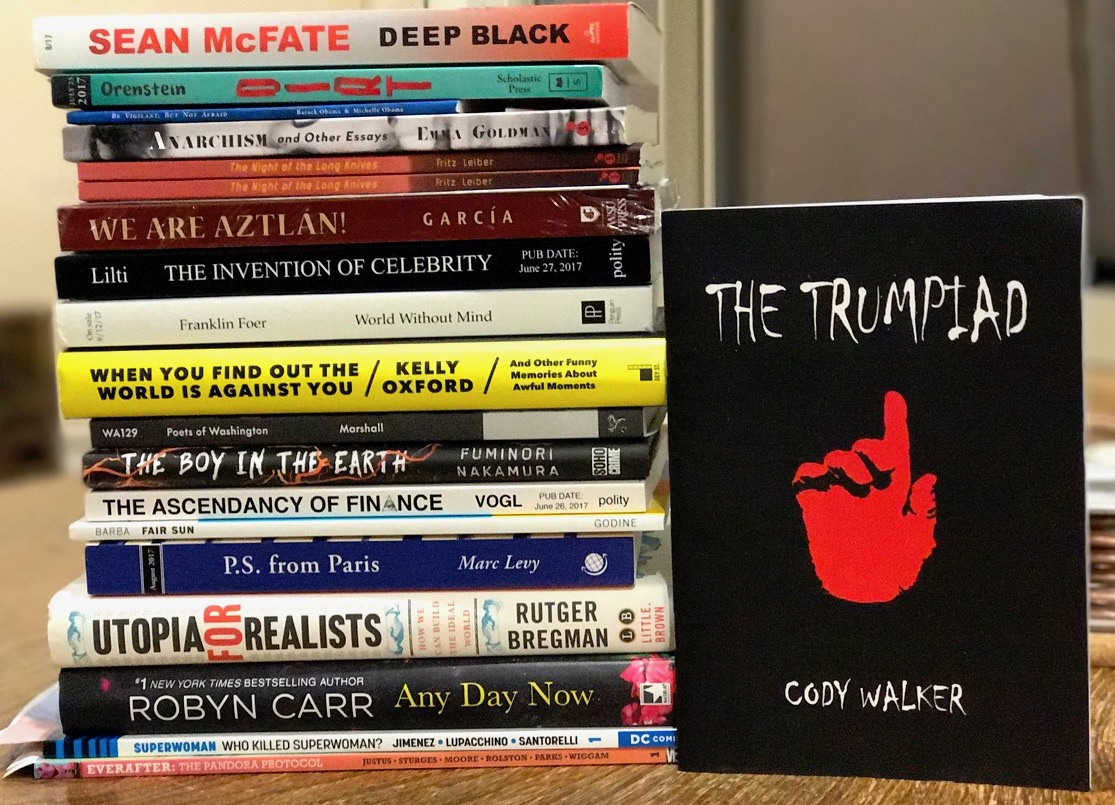

Mail Call for April 18, 2017

Buckle in, folks. This one's a doozy:

Seattle, step by step

Published April 18, 2017, at 12:30pm

From Madam Damnable’s Hotel to Profanity Hill, a new guide walks you through Seattle history.

Some stories just deserve a book

A couple weeks ago, I listened to the podcast S-Town. It was exactly as compelling as you’ve heard — a story of death and crime and poverty and hatred and mental illness. Of course the story of S-Town is more complex than just what’s in the narrative— the way it’s told, the elements of the story that don’t appear in the audio, are part of the podcast’s puzzle-box fascination.

It occurred to me as I was listening to S-Town, though, that fifteen years ago, before the dawn of podcasts, the story almost certainly would have arrived in the form of a book. In fact, you could easily argue that the story of S-Town would likely be better served in book form.

Podcasts are terrific ways to relay certain kinds of information — interviews, current events, deep dives into a single topic. But the nuance of S-Town isn’t especially great for a podcast, which is a medium that continually moves forward. Books are better-suited to address the kind of complicated questions raised in S-Town — the recursive questions of reporting and ethics and respecting the wishes of the dead while honoring their legacies.

S-Town is in the spirit of two recent true crime books by local authors: Eli Sanders's While the City Slept and Claudia Rowe's The Spider and the Fly. Both of those books provided context, introspection, and complex narratives in a way that S-Town could only hint at. It's frustrating to feel that there's more just outside the reach of the storyteller, and that certain aspects of the story aren't covered as thoroughly as they should because of the limitations of the medium.

The characters and situations in S-Town are rich, deep, and they possess many levels. They deserve the richness, depth, and nuance that only books can provide.

Technology

All the cell phone towers are pagodas

from the top floor through my near-sighted eyes—

blue, white, red shimmering houses

for ancient gods among the fir trees and dogwood.

They climb the hills to the cemetery, carrying

the voices of the living far above the lost

chatter of those already gone before us.The words are like raindrops in a summer storm

here then gone, sadness borne away

over the continents. And love

or the failure of love, wounds and caresses.

The seas wander underneath.

Somewhere in this forest of voices

a pen is writing in blue ink.

An evening with Laird Hunt

Sponsor Third Place Books, up in Lake Forest Park, is hosting an exciting evening with author Laird Hunt, to talk about his latest novel The Evening Road. Hunt will be joined by Third Place Books managing partner Robert Sindelar. It happens next Tuesday, April 25th, starting at 7:00pm.

If you know Hunt, you certainly need to introduction to his work. He's the author of six novels and a collection of short works. He works across various literary genres, always working to reach new, exciting ground. No doubt this is going to be a fascinating conversation with a compelling writer. Find more information on our sponsor's page, and make sure to put the 25th on your calendar.

Sponsors like Third Place Books make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. We have two dates for March we'd love to sell, and they're currently discounted. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Lunch Date: Persecuting liberal elites at a fancy banh mi shop

(Once in a while, I take a new book with me to lunch and give it a half an hour or so to grab my attention. Lunch Date is my judgment on that speed-dating experience.)

Who’s your date today? Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People? by Thomas Frank. (Frank will be reading at Town Hall tomorrow night.)

Where’d you go? The Tigerly Ox, a newish Vietnamese lunch counter on Madison.

What’d you eat? The Tigerly Ox's fancy version of a steak banh mi. ($8.20.)

How was the food? Great! You should be warned that the Tigerly Ox doesn't serve the so-simple-it's good version of the banh mi that you can pick up anywhere in the International District. This is on crusty, crunchy bread, it's made from fancier ingredients than your typical four-buck-banh-mi, and it's loaded with a nice fishy umami kick from the paté. It's a lot more filling than the typical banh mi, but you should be warned that it doesn't scratch the particular banh mi itch you get when you want a cheap sandwich on airy, cheap French bread.

What does your date say about itself? From the publisher’s promotional copy:

... Drawing on years of research and first-hand reporting, Frank points out that the Democrats have done little to advance traditional liberal goals: expanding opportunity, fighting for social justice, and ensuring that workers get a fair deal. Indeed, they have scarcely dented the free-market consensus at all. This is not for lack of opportunity: Democrats have occupied the White House for sixteen of the last twenty-four years, and yet the decline of the middle class has only accelerated. Wall Street gets its bailouts, wages keep falling, and the free-trade deals keep coming.

Is there a representative quote? "Democrats have been wondering who they are and squabbling over what they believe for virtually my entire life. It has taken them years to get to wherever it is they are today; years filled with quarrels and vituperation and occasional bouts of manic self-love. It has required long periods of slow evolution, usually in the wrong direction; runs of rapid but lousy choices; epochs followed by a savage Thermidor in which hard-headed party toughguys promoted different fad ideas that turned out to be even worse."

Will you two end up in bed together? God, I have no idea how I didn't read this book when it was realeased in hardcover last year. Frank accurately identifies the problem with the Democratic party — elitism and a wrong-headed meritocracy — and his diagnosis is so eerily right-on that it seems like he has access to a time machine. This book explains why Hillary Clinton lost the election, and it was published a year before Hillary Clinton lost the election. It's fascinating stuff, though I hope Frank has some prescriptions for how to fix the problem, because while he's great at being right — seriously, this book is filled with rage and disgust and it's wildly entertaining — it would be even better if he turned out to be helpful, too.

One month since her passing, Seattle's literary community still mourns Joan Swift

When news broke last month that Joan Swift had died, the Seattle literary community erupted in outpourings of grief. A shared sensation spread quickly around Facebook that something momentous had passed with her. At 90 years old, Swift was well-loved by many generations of Seattle writers, and she provided a direct link to the history of Northwest literature. She was one of the last living writers to learn directly from Seattle poetry godfather Theodore Roethke, and she shepherded generations of writers out of anonymity and into maturity.

Tess Gallagher (on the left on the photo) met Swift (on the right) in 1963 when both had enrolled in what would be Roethke’s final spring poetry workshop. Roethke developed nicknames for several of his students, and “he called [Swift] ‘Mother’ since she had two children and was a bit older than others” in the class, Gallagher recalls.

Gallagher was 20 years old, and one of the two youngest students in the workshop. “Joan was extremely kind to me and took me under her wing,” Gallagher writes in an email. “We sat near each other in the class and it helped me greatly that she took an interest in my poems and clarified things that were asked of us by Roethke from time to time.” She doesn’t know what she would have done had Swift not “made me welcome in her quiet, bemused but affable way.” Swift and Gallagher have been friends ever since. “I considered her a close friend with whom one could share life details and gossip a bit with and just laugh with in a special way,” she writes.

The Puget Sound region is full of stories like that — tales of how Swift reached out to others, and how that first act of kindness blossomed into a lifelong friendship. Seattle poet Esther Altshul Helfgott first saw Swift read at the Frye around the year 2000, and they became fast friends. Helfgott started the It’s About Time open mic series at Ravenna's Eckstein Senior Center a quarter-century ago as a way for new writers to practice their craft on a public platform. She says “some poets and writers of Joan's caliber wouldn't give us a second look, but Joan read for” the series on multiple occasions; she especially appreciated that Swift “treated me like an equal. That doesn’t happen with well-known people in the literary community. She was just so warm and giving.”

Swift had been a high-profile poet in the Seattle area for so long that her monolithic presence could sometimes overshadow the very fine, delicate work in her poems. “Her use of language is so beautiful and lyrical, and the warmth of her personality is reflected in her language,” Helfgott says.

“She is so entirely present in her encounters within the poem that, reading her poems, you accompany her at a high intensity,” Gallagher says. “Her endings often sink the poem deep into your memory so the poem is carried and not released. She is so exact in her image and language that one immediately trusts her, follows her. Her voice has its truth seemingly embedded within it.”

The honesty of Swift’s voice opened doors for other poets. Shortly after news of Swift’s death broke, Sherman Alexie told me about the impact that her work had on him as a young poet. “Way back when, in college, or just after college, I read a Joan Swift poem about eagles having sex as they plummet toward the earth, how they sometimes forget to uncouple and crash to their deaths,” Alexie says. “And I remember thinking, ‘Wait, it's cool to write a poem about eagles fucking to death? Awesome!’ Joan introduced a new rule of poetry to me. Or broke the old rules. Or both.”

“She writes about difficult subjects that others might shy away from,” Gallagher says, citing the poem “Shin-Ichi’s Tricycle” from Swift’s forthcoming book from Cave Moon press as an example. “That ending makes us wear the death of the little boy in the bombing of Hiroshima and she convicts us of us death in such a deadly no-escape way in her ending. She’s a take-no-prisoners kind of writer.”

Swift wrote candidly about rape, Gallagher says, “long before other women would write about it.” Helfgott says that one of the last poems Swift ever completed, “Sometimes a Lake” is one of her most courageous. The poem addresses the suicide of Swift’s daughter, Laurie, and it “is so gorgeous. When she would talk on the phone about Laurie, there was nothing in her voice or her words speaking to me that were like that poem.” In the poem, Swift captures the moment when she goes through Laurie’s effects, looking for a greater meaning that isn’t there.

These boxes are almost empty—

just air and losses.

But here’s a photo album where you’re smiling

with friends, your borderline disorder group.

Everyone I talked to remarks that Swift was working right up until the end. At 90, by all accounts, she was still as sharp a writer and reader as she’d ever been. Cave Moon Press publisher Doug Johnson was working closely with Swift on a volume of poems titled The Body that Follows Us that will be published next month. On Tuesday, May 16th, Open Books in Wallingford will host a memorial service for Swift that will serve as a launch for the book.

Johnson says that Swift was thoroughly involved with the editing process. Unlike some of the books he’s published, Swift “handed me an extremely well-formatted book,” one that was clean and well-formatted and basically ready for publication immediately. But they passed the manuscript back and forth for months, editing it and talking about fonts and making sure everything was perfect.

“Joan very much wanted to get it extremely right,” Johnson says. “She wanted to carry it through to the best of her ability.”

Heidi MacDonald at the Beat says that Sarah Glidden's Rolling Blackouts has won the Penn State University Libraries' 2017 Lynd Ward prize. MacDonald says the prize is given to "the best graphic novel, fiction or non-fiction, published in the previous calendar year by a living U.S. or Canadian citizen or resident. It’s definitely one of the most prestigious awards for a graphic novel given out each year."

We've been talking about Sarah Glidden for a long time here on the Seattle Review of Books. You can find our author page for her here. I reviewed Rolling Blackouts on its release, and I interviewed Glidden about the book at the Rolling Blackouts Seattle launch party.

The Sunday Post for April 16, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Going It Alone

I-walked–2,000-miles-and-lived-to-tell-the-tale is a genre full of clichés. Crushing physical discomfort? Check. Naïve decisions that lead to near-disaster? Check. Ultimate success and personal transformation? Check. Check check check.

Friend of SRoB Rahawa Haile’s story is different. Haile — black, Eritrean, queer — hiked the Appalachian Trail alone in 2016, covering thousands of miles of wilderness dotted with pro-Trump signs and Confederate flags. Those oases of “civilization” were more terrifying than rattlesnakes and switchbacks. So was her return to an urban world in which Donald Trump had been elected president.

Every day I eat the mountains, and the mountains, they eat me. “Less to carry,” I tell the others: this skin, America, the weight of that past self. My hiking partners are concerned and unconvinced. There is a weight to you still, they tell me. They are not wrong. My footing has been off for days. There were things I had braced for at the beginning of this journey that have finally started to undo me.

Also read: Haile’s incandescent short essay on carrying books by black authors and the weight of the present moment across all 2,000 miles.

How 'S-Town' Fails Black Listeners

Did you love S-Town? I did. Like Maaza Mengiste, I listened “with my own childhood experiences in mind” — a wealth of stories and memories from Jackson, Gulfport, Meridian, some beloved, some angry, some sad. That’s what S-Town is meant to do, Mengiste says: make us think about how we’re living, who we are.

What if who you are is a gaping absence in the story, though? What if who you are is black? Here’s what S-Town sounds like to that set of ears.

This podcast is supposed to be about all those things we do not know of a person, all those things that we cannot imagine that make up their totality. In producing this podcast, however, the creators made an assumption that rings false, that frankly, rings white: that it is possible to move through this land and simply tuck race into a corner until it's convenient.

Confessions of a reluctant gentrifier

Eula Biss lives in one of Chicago’s “most diverse neighborhoods,” which means she and her husband, both academics, are able to afford an apartment with a view of Lake Michigan. They are the leading edge of gentrification, and they dread the cultural and social losses that come with it. This will feel familiar to many Seattleites …

“Gentrification” is a word that agitates my husband. It bothers him because he thinks that the people who tend to use the word negatively, white artists and academics, people like me, are exactly the people who benefit from the process of gentrification. “I think you should define the word ‘gentrification,’” my husband tells me now.

I ask him what he would say it means, and he pauses for a long moment. “It means that an area is generally improved,” he says finally, “but in such a way that everything worthwhile about it is destroyed.”

Telling Right from Wrong

Yonatan Zunger has been reflecting on the definitions of “right” and “wrong” for several decades. He has some good, practical advice for determining which is which, or at least thinking more carefully about the question. And some very clear views on the real-world consequences of muddy ethical thinking.

I’ve been regularly surprised at the depth of people’s urge not to discuss things like institutional racism or sexism, or generational poverty, or how power imbalances in society mean that seemingly “identical” behaviors are in no way identical. But if you fail to understand this, then you will routinely engage in “identical” behaviors which are anything but — for example, expecting that someone move in with their family until they can get back on their feet, when not everyone has a family they can do that with. The harm you cause this way may be entirely surprising and unclear to you, because you never learned about the things which cause your actions to lead to it. But if you had the chance to learn it and didn’t, then the moral bill is on you.

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Alaskan Way Viaduct

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

It never should have been built. Think about Vancouver, who denied the highway madness of mid-century America. Think about the Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, where a group of residents banded together to fight a highway bisecting their neighborhood. Then think about Seattle where, in a fit of veiled hatred towards beauty and all things natural (e.g. the large body of water at our feet), we built this 50 foot wall of concrete to block us from having to see it.

But, look, times were different then. My parents (with sisters and me in tow) moved from Los Angeles to Bellingham in 1982. When they bought their house up there, they found that houses on the side of the street without a view went for more money than ones with a view. Why? Nobody wanted to look at the working bay. It was industrial. It was polluted. Same in Seattle — so why not just build a modernist brutalist ribbon to partition the clean streets of downtown from the horrible ennui of a polluted, working Elliott Bay?

And times were different in that it was post war, and the most modern idea of great living was grouping all of these places people wanted to go into superbundles and people could drive to them, because everybody was buying cars like they were raffle tickets to Hamilton. Take your private world with you wherever you go! Cars were everywhere, and no "normal" family wanted to live in the city any more. It was the start of white flight, suburban dreams, and the inhuman drive towards putting culture out to pasture, for the possibility of a square of manicured grass with a habitat box plopped in the middle. Surrounded by pipe-smoking, lawn-mowing, casserole-baking, PTA-attending white people just like themselves.

This was a problem for cities: people who lived there, shopped there, ate there, worked there, and paid taxes there, were suddenly only working there, and they took their tax money with them to the burbs. So, let's build a highway to bring them all back, so that they can drive into town in comfort, and repatriate that money that had escaped. Except, of course, the highways went both ways, so people would just go home with whatever money they didn't spend on Frangos and fresh salmon.

There are people who love the Viaduct. Someone wanted to turn it into a park, like the Highline in New York, which is stupid because the Highline isn't in imminent risk of falling down when breathed on wrong. The Viaduct has been, in effect, condemned, for years, and is far beyond its functional life. And underneath, the dim, cluttered, depressing basement of downtown, is like a cyberpunk novel stripped of interesting technology. All sorts of things shrink there for lack of sunlight, from people just trying to get by, to people just trying to get one over.

But recently, an amazing thing happened: the most expensive, and largest bore, drilling machine in the world actually broke through the retaining wall of its exit pit, in a dust-throwing storm of earth crunching. Four billion (and counting) dollars later, we have an underground replacement for the aging stacked highway (which opened four years earlier than the Cypress Street Viaduct in Oakland, that collapsed during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, killing forty-two people), and in a few years the dismantling of our stacked utopian fifties vision of he world will be stripped from our twenty-first century streets.

I say good riddance, and I just hope we get rid of it before another earthquake strikes here. Very few of the politicians who campaigned so hard for that project to happen are around to take the heat for its overruns, and the inevitable lawsuits that we, the taxpayers who voted against it, will be stuck dealing with.

But of the Viaduct there is one thing I will miss: it is the greatest egalitarian people-owned view in Seattle. If you have a car that moves, you can take it in. If you don't, hop on a bus that travels part of it. Because when it's gone, the ability to look out over Elliott Bay on a beautiful day — the Olympics appearing as close as Bainbridge, the sparkle on the water dancing, orca breaching alongside ferries, barges, cruise and container ships — that view will only be available to the highest bidder, and the bids are going up sharper than the profit line in a New Yorker boardroom cartoon.

All we'll be left with are stories.

Today's prompts

It was the one road in Seattle you could open the throttle, if there was a cop ahead, you'd spot them. It was 3am. There were four cars, hopped up with engines growling. When the flag went down, they hit 99 just north of the Aurora bridge. First to make it to West Seattle was gonna win, and the Viaduct was where they really put the hammer down.

It was all fenced off, where they were building the old highway. He knew, in the morning, a big concrete pour was starting. He pulled, heaving the bulky form in the bag, and cut the fencing. All he had to do was dump this stiff down the hole, and tomorrow, it would be gone forever.

As meet-cutes go, this one was weird. They owned identical cars. Maybe that wouldn't be notable in Seattle if they were Subaru Outbacks but perfectly maintained 1960s Mercedes-Benz 230sl convertibles? An accident was blocking northbound, and the first time they pulled up next to each other, they caught eyes and laughed. The second time they yelled, back and forth, the white car driver initiating. The third time, the driver of the red car sent a paper airplane flying across, landing on the passenger seat of the white car. On it, a phone number.

All he wanted to do was walk it. From the on-ramp to the off-ramp. Just walk it like a person walks any road. The cops saw it different, thought he was a suicide. But come on, man. Would a suicidal person be wearing a yellow safety vest? All he wanted to do was walk and take in the view. And now, he was gonna have to make his way through a bunch of cops to do even that simple thing.

The shaking felt like a flat tire, at first. She had just entered the southbound lanes where they go under the north, but when she saw a telephone pole, next to the highway, swaying, she knew it was something more. She felt movement too strong, too intense. Too wrong. Traffic slowed around her and she laid on the horn. Move, you idiots, move! She looked in the rear view, at her son, sleeping in his car seat, oblivious. There was no way she was gonna let a damn highway win. She pressed the gas around, she had just enough room to get around that Tesla. She laid on the horn and went for it.

Alec Baldwin reads tonight at the Paramount. Let's remember that Alec Baldwin is terrible.

Alec Baldwin reads from his new memoir Nevertheless at the Paramount tonight. It's sold out.

If you're thinking about buying Baldwin's memoir, you should know that Baldwin is openly complaining about the job his editors did on the book. Danuta Kean at The Guardian notes:

The 59-year-old actor has attacked his publisher HarperCollins, accusing the editors of poor proofreading. In his first post on a Facebook page set up to promote his new autobiography, Nevertheless, he claimed the published edition “contains SEVERAL typos and errors which I was more than a little surprised to see”.

Editing is thankless work. Nobody ever comments on how few errors they find in a published book. They only complain when they do find errors. And that's basically an editor's lot in life: an editor's job is to fall on their sword when a book is released with an egregious error. Editors take the blame, absorb the insults, and then move on, knowing full well that they'll be responsible for any errors in the next project, too.

But let's be clear: a writer who publicly complains about his editors is a shit writer. I find it hard to believe that all those errors Baldwin complains about were introduced into the text during the editing process. If some of those typos and misstatements are his, then he is whining about someone not cleaning up the mess that he made. And that's never a good look.

Baldwin is a good actor. But I will never understand America's willingness to feign amnesia when it comes to Baldwin's character. This is a man who says horrible things to strangers. This is a man who says horrible things to his own daughter. This is a writer who pubicly derides his editors.

Why would I bother reading his memoirs — particularly memoirs that, by his own admission, are poorly written? — just because he does a so-so Trump impression every couple of weeks on Saturday Night Live? Sorry, no. Life's too short.

The Help Desk: What should we call serious comic books and non-fictional graphic novels?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Everyone calls comics “graphic novels,” but a lot of great comics, like Persepolis and Fun Home, are non-fiction. So “novel” isn’t right. But some comics aren’t funny at all, and so “comic” books doesn’t make sense, either.

A couple of bookstores in town call their comics sections “graphica,” which seems really pretentious. Is there a better name for these books? Am I worrying about nothing?

Mark, Wedgwood

P.S. Sorry for the inanity of the question. I’m aware that the world is sitting on the precipice of Armageddon and a madman is in the White House, but I’d like to think we can walk and chew gum at the same time, metaphorically speaking.

Dear Mark,

Life is full of irritating incongruities like the one you describe – tinfoil is really aluminum, jellyfish are angrily neither, and pro-life politicians who would defund Planned Parenthood are really smarmy fuck-weasels who despise half their constituency.

Sometimes I wish I was poisonous, you know?

But personally, I like the word "graphica," which, as you point out, is more inclusive than "graphic novel" or "comic book." It reminds me of "novella," an approachable word that means, "I know you're a very busy person but I am a creature of few words and I would love to entertain you while you are taking a shit." Metaphorically speaking.

Kisses,

Cienna

P.S. Have you read The Impostor's Daughter? I highly recommend it. I also highly recommend hissing as a form of communication and using Dentine Ice as a martini garnish.

Portrait Gallery is traveling this week

Our superstar Portrait Gallery artist, Christine Marie Larsen, is traveling this week, so there's no new painting today. Instead, please peruse the 72 portraits in our archives.

Book News Roundup: This book smells awfully skunky...

Seattle-area newsletter The Evergrey is looking for your input on local small businesses to profile. We're not saying you should go and suggest your favorite small bookstore or anything, but...you should go and suggest your favorite small bookstore. Deadline is Monday April 17th, and the businesses will be profiled on May 1st.

Brangien Davis at Crosscut explains what happened when a title from Seattle publisher Wave Books won the Pulitzer Prize.

The arts levy, a proposed King County ballot issue which would have funded "arts and science programming targeted at poor people and seniors," didn't survive a committee hearing this week.

The TV Writers Guild might be going on strike soon. We stand with all unionized writers.

Whatever happened to Google Books?

Some men's rights dipshit reviewed Harry Potter and his review is virtually unreadable, unless you enjoy bird-brained sentences like this:

Harry Potter was perhaps the first major shitlib touchstone to vault willing cuckoldry into the wider culture as some kind of moral imperative; it was beta orbiter Snape, a man with the worst case of oneitis imaginable because he was in love with a dead woman who when alive wanted nothing to do with him, who vowed to look after Harry, (the child of his oneitis by another man Snape hated), out of a misplaced sense of loyalty and maybe hope for an afterlife consummation.

- I'm sorry, but a scratch-and-sniff book of marijuana sounds disgusting.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The unhappiest children's books in the world

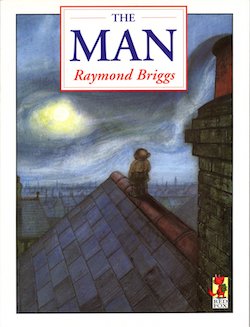

Like so many of the best books, I found it hidden behind a couple outdated computer programming manuals in a Goodwill. It’s a tall, slim hardcover book with a torn dustjacket. The cover is a soulful color sketch of a tiny figure standing on a roof staring out at a cloudy night sky. It says in big letters at the top, The Man, and below that, in smaller print, the author credit: Raymond Briggs.

You likely know Raymond Briggs for his wordless children’s book The Snowman, but Briggs has a long and colorful publishing history. He’s written and drawn dozens of books, and he’s been publishing from the 1960s to, most recently, 2015. Many of his books — including The Man — are out of print in the United States.

Because they deal almost exclusively in the interaction of words and pictures, most children’s literature is, in some form or another, comics. But Briggs’s work shares more of a common vocabulary with modern comics than most other authors for children. His books have multiple panels per page, and dialogue often depicted in word balloons, and the work features other comics traits that you don’t find in more “traditional” kid’s lit.

The Man, though, is a little bit of a departure for Briggs in format: the book features experimental layouts — often with one large illustration per page and dialogue typed out, in different fonts for each character, down the middle of the page. It’s less like a comic and more like a stage play. The book keeps its scope fairly intimate, too: it’s the story of a young boy who, one day, finds a bossy little naked man living in his room.

The man, who only answers to Man, demands that the boy fashion him some clothing out of an old sock and a rubber band, and then he proceeds to complain even more: “I wish you had real marmalade,” he whines when the boy smuggles some food up to him. When the boy wonders aloud if Man is a Borrower, he angrily spits, “Pah! Stories! I hate them.”

Man’s continual insistence quickly grates on the boy, and they begin to fight. “You exploit your smallness,” the boy yells at Man, “You know how to use it. You manipulate people by it. You manipulate me for your own selfish ends.” Man retorts, “You make out you are being kind, generous and caring when all you are doing is using my smallness for your own ENTERTAINMENT. You don’t care for me as a PERSON! To you, I’m just an entertaining NOVELTY!”

The Man’s tone is all over the place: it’s hilarious, and tense, and realistic, and more than a little upsetting. But it finally settles on a deep and melancholic sadness that speaks to the sacrifice we offer to others: even those we love most — those tiny people who show up naked and willful — can get on our very last nerves, and sometimes we lash out in uncomfortable ways. That’s a special kind of sorrow. The last page of The Man speaks to a sadness that I’ve never quite seen represented before in children’s fiction.

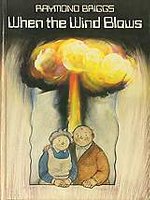

Briggs is no stranger to uncomfortable topics. Another of his out-of-print classics, When the Wind Blows, is, if anything, even more depressing than The Man. Wind is the story of an old British couple living in the countryside. They’re not especially deep or introspective people, but they’re law-abiding citizens who seem to enjoy each others’ company. One day, there’s an upsetting story in the news reports: nuclear war is breaking out.

A bomb drops not far from the couple, but far enough away that they’re not killed in the explosion. So they set about doing what any rule-following British citizens would do: they build a makeshift shelter in their home and they hunker down “for the 14 days of the National Emergency.”

Everything around them collapses — the radio stops working immediately and the nearby town’s supplies are wiped out soon after the first hit — but they continue living their lives: the wife wraps pillows in their shelter in plastic because “I don’t want finger marks getting all over them.”

Like The Man, Wind does not have a happy ending. Unlike The Man, Wind is well and truly apocalyptic. The couple start showing signs of radiation poisoning, but they still trust in the rules. “We’d better just lie here and wait for The Emergency Services to arrive,” the wife says. “Yes, they’ll take good care of us,” her husband replies as they huddle in potato sacks for warmth. “We won’t have to worry about a thing.” Those institutions will not save them. It’s dark. Really dark.

While not as bright as The Snowman, Briggs’s Fungus the Bogeyman is considerably lighter than either The Man or Wind. It’s the story of a bogeyman community that treasures the opposite of everything our society adores. Fungus’s wife wakes him at dusk on the first page of the book. “Time to get up, Fungus my dreary. It’s nearly dark.”

Fungus wakes up complaining: “OOOH! What a night that was! This bed has almost dried up!” His wife agrees, “I know, drear. It needs more slime.” Fungus walks over to a bin filled with cold water and pulls out his clothes for the day. A caption helpfully informs us, “Fungus inspects his trousers which have been marinading overnight." Fungus, his face inside a pair of pants, exclaims approvingly, “Mmmm! These really stink!”

Bogeyman follows Fungus through a typical day in his life. Throughout the book, captions explain Bogeyman culture, from the fact that they “cultivate boils on the back of the neck” to an account of the rotten grapefruit and “mouldy” cornflakes they eat for breakfast.

As an artist, Briggs is having a lot of fun here, experimenting with wild panel layouts and exaggerating the moribund dreariness of bogeydom culture. The expressionless dot eyes and upturned pig noses of his bogeymen give them a cartoonish appeal. It’s easy to imagine children falling into this book and being swept up in the many shades of sick-making green on every page, wondering at the intense oppositeness of Fungus’s world.

The best part of Bogeyman is how normal it all is. While Wind feels like a scathing refutation of humanity’s ability to remain docile in the face of global Armageddon, and while The Man revels in the way it upturns societal commitments, Bogeyman takes a sort of pleasure in the everyday rituals and cozy domesticity of its main characters. It’s unique in all of Briggs’s work in that it finds a sort of peace in its miserableness. It’s okay to be unhappy, Bogeyman says, as long as you’re okay with being unhappy — and don’t let anyone spread sunshine on your rained-out parade. It’s your party. You can cry if you want to.