Ah — the sea!

Let us begin in the library.

Western Washington University was my second home when I was a teenager. I spent a lot of time on campus, which is particularly ironic given that I was a terrible student who was dedicated to the art of flunking out of high school. The university promised a broader culture than even my progressive and arty high school did. It felt limitless, and of the future.

I loved visiting the libraries. College libraries, so vast, so well stocked, so precisely organized, so many volumes covered in anodyne ballistic bindings, muted greens and reds and blues, white-ink stamped on the spines, meant more to stand time and use than to entice a buyer. The smell of them, of preservation and availability, was powerful.

There were many wonders in the library, including lascivious bathroom graffiti offers from for men, listing specific places and times in the stacks you could visit for anonymous sex. How antiquated, in today’s age of Tinder, to think back on this heyday of AIDS and clandestine closeted meetings. How fraught it must have been for discovery; how likely it must have been that you would meet a violent homophobe, or evangelical hoping to pray and convert, or security guard who saw the graffiti, as opposed to another nervous gay college boy hoping for some love, affection, and expression of desire (although, all three of those might have also shown up for the desire).

Personally, I sought solitude in the stacks. I looked for knowledge I didn’t know existed, bestowed on me by chance. I liked to get lost, to wander, and to pull books at random from the big, industrial steel shelves. I loved the way different sections felt, based on seating, windows, and lighting. It was like walking through middle earth, and getting good or bad vibes depending on how close to Mordor you were.

I remember, one day, seeing the title The Devil’s Dictionary and pulling the thin volume down, finding Ambrose Bierce’s biting cultural criticisms, sometimes so naked and cynical (“BORE, n. A person who talks when you wish him to listen.)”, other times so subtle that they were like insults you could show to a bully and the bully would think themselves complimented (“FUTURE, n. That period of time in which our affairs prosper, our friends are true and our happiness is assured.”).

I felt, then, like the only person who had discovered this book. It belonged to me, not from a recommendation or review, but through my own chance and eye. Nick Cave calls the songs that felt like they were speaking only to him his “hiding songs,” and there is a special connection to books you find by yourself, that speak to you deeply.

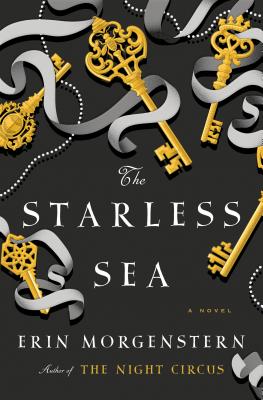

In Erin Morgenstern’s new book The Starless Sea, Ezra Zachary Rawlins — his chapters always starting with an invocation of his whole name, something Lyndsay Faye, in her New York Times review didn’t like: “All three of Zachary Ezra Rawlins’s names march forth at the outset of every chapter in which he is featured, in case one forgets he is the hero. (One does not forget.)”, but I found cagey and rhythmic and a bit of clear signposting so you know which world you are standing in the doorway of — finds a book on the stacks in his university library (oh, that feeling! It all came back to me reading). The book he finds has no author, no published date. It holds many stories, one of which appears to be about him.

Finding the book is an invitation: he enters into a world of mystery, draped in literary themes and metaphors, decorated with a puzzle of wayfinding iconography. He finds a whole lot of style, in there. He finds a story. Morgenstern’s new work is an evocation, an ode, a prayer, that tells the story of Ezra Zachary Rawlins as a way of talking about how we feel about books, and what we want from them.

This is not a book for those who want a puzzle who might fit together and resolve. This is not a mystery whose last page will reveal that which was unconsidered before. This is a book that, with a deep breath, enters the liminal space of your mind and plays with how you feel about books and how you think about reading.

It is a fable, not a yarn. The journey is, more or less, the destination. The opening will appeal certainly to the mystery box readers, who want to have a problem laid before them and solved as they look on. But for those readers, it will be a disappointment ultimately, because this book is a song, not a sermon. It won’t end with the box laid open, allowing you to marvel at its intricate woodwork (or rather, it does, but you’ve kind of descended so far into the workshop that you’re looking at raw materials, not the workwomanship).

On NPR, Amal El-Mohtar (who enjoyed the book for many reasons I list here) didn’t like this aspect of it: “Early on, this is exciting, and did indeed succeed in making me feel like I was playing a puzzle game, being guided through a beautiful labyrinth of harbours and honey and bees. Later on, I kept expecting the story to resolve in a satisfyingly meta way — which it refused to do....”

The Starless Sea will, like a spell, take you to a dreamland of books, and if that is a place you have ever desired to go, then you, like me, will likely find the experience somewhat irresistible.

This sounds mild, what I’ve described, in terms of praise, but it is not. In fact, it is a deep gratitude. Perhaps, though, I was too prescriptive. The book does resolve. The stories do tie together. You will not wonder about the characters in the end. You just will wander out of the mold of the heroes journey, and find that the mold, itself, was made by someone with an inquisitive hand.

Maybe I can get at this better by illustrating with another personal story. As a young reader, probably middle-school aged, I picked up a book that seemed to offer a promise. It was a collection of stories based around the concept of Dicken’s The Old Curiosity Shop, which I hadn’t read (nor, living in Bellingham at the time, had I visited Seattle’s own tourist destination of ye same olde title). The promise offered was one of mystery, magic, the unknown. It had a very specific shape and flavor, in my young mind. Although unable to articulate it then, I wanted an evocation, a portal through which I would experience wonders. The kind of experience you might get with, depending on your taste, Rowling, or Borges, or a Percival Everett short story.

So, I eagerly sequestered myself with the new book and started reading, only to realize that what was promised is not at all what I was receiving. I didn’t know, then, how to approach speculative fiction collections — how they are fertile grounds for experimentation and finding new voices, how they are driven, primarily, by theme and a sense of play.

The failing here, I am sure, is my own maturity in reading. Also, a failing of marketing, perhaps, where the jacket promises something the interior doesn’t deliver. I can’t even say the stories inside were bad or good — they were just not what I was expecting. It is easier to spark the desire for wonder than it is to fulfill it.

Books are lore, they’re promises. Ask any reader whose library holds more books than they will ever read (I am such a reader).

The promises are stacked on the spines of books you’ve already read, and the promises of the kinds of books you wish you could read, like when you finish a book you love so much and want to read an alternate universe version of it, where you don’t know what will happen, but that will feel the same to you. Each reader absorbs and builds on their own reading history, but one of the most precious is the feeling you got reading when you were very young and a book first cracked your mind open to possibilities larger than yourself.

What we hate when we open a book is that the promise we expect is not fulfilled by the volume within. And over time, what we expect has been shaped by massive forces of storytelling in our culture. We are becoming accustomed to a particular form of story, one that is not moral or necessary, one that is fine and fun and enjoyable and should exist, but it is only one kind of story.

Morgenstern’s latest works like the zen koan: she describes the bowl by describing the space around the bowl. In doing so, she has described wonder.

Writers do a lot of talking, and workshopping, about how hard it is to write a concise, tight book. Like, say, a mystery, where there is a murder, and misdirection, and a central character whose story you are interested in, and the world around her that you come to know and appreciate, and the personal danger she puts herself in on her way to solving the murder — which she always does (unless it must be delayed for a sequel).

To write that book in a satisfying way, either by doing something new or by doing something old so well that we can appreciate the form, is incredibly difficult. To make an artistically successful hero’s journey film in Hollywood is, statistically, nearly impossible. Only Pixar, perhaps, has cracked the code on how to do it consistently and repeatedly. It does not matter how much money you throw at the problem. You have to have a process and trust the writers.

Rarer still, however, are the David Lynch’s of the world. The artists who get at something vital in the making of the art, who are less concerned with a pattern or neatly tying something up, and more compelled by the way the story is told. The aforementioned Nick Cave is in this world, in music. As is, perhaps, Borges, in writing. Seattle’s own Rebecca Brown splashes in this water, and does a marvelous job of it.

But where Lynch plays in the dream/nightmare world of cultural fear, Morgenstern plays in the world of fables — but not classical fables or fables of old Europe, her fables are of Twentieth-Century storytelling. Of New York, of college, or the promise of story.

Critical reviews feel personal to writers, because the assumption is, often, that the writer could have done a thing, but failed to, by lack of talent or ability. A well-written bad review finds grounding and evidence in this, and, of course, is centered around the reviewers point of view. Here, on this site, we are naked about this — we want reviewers to look at the world through the lens of the book, bringing their own life and experience into the review. So, I bring my own stories in to reinforce why I found Morgenstern’s work necessary where others found it incomplete, or flawed.

We need books like Morgenstern’s, that create their own mythology, that refuse to play the game they are expected. Natasha Pulley, in her very positive Guardian review (she liked many things that I liked about this, as well) points out “...this is the very opposite of the world-building logic we normally expect of fantasy writing. Terry Pratchett, if not the king then definitely the senior jester of the fantasy royal court, famously advised that if you’re going to write about flying pigs then you ought to consider the traffic disruptions. The Starless Sea refuses to do so. It demands that its readers interpret it in an older way....”

Yes, it’s true, they are older stories in that sense, but they are also decisively modern. In our largely secular world where we have very little sense of wonder, and where our daily politic is an intricately built mythology of lies, a book that refuses to play along as expected is a joyful rebellion. It is, as I’ve said, an evocation and invitation, and losing yourself in its moments is joining in an act of rebellion.

If the sea is starless, there is no way to guide yourself across it. A sailor, here, should be content with wandering its honeyed swells.

Let us end, then, in a book. The page of Emily Dickinson’s collected works open to this:

Futile - the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah - the Sea!

Might I but moor - tonight -

In thee!

Martin is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He’s a novelist (his first, California Four O’Clock, was published in 2015 by a successful Kickstarter campaign). He designs websites, apps, and other things for a living.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound