Bernie Sanders is the last Democrat standing

Never in the history of Seattle readings has an author so brazenly stepped on his own introduction. Last night at University Temple United Methodist Church, University Book Store CEO Louise Little was seemingly just getting started with her introduction for Senator Bernie Sanders when a raucous wall of applause broke out in the back of the church and proceeded to the front of the building. It was so loud, and so continuous, that Little’s voice was entirely drowned out.

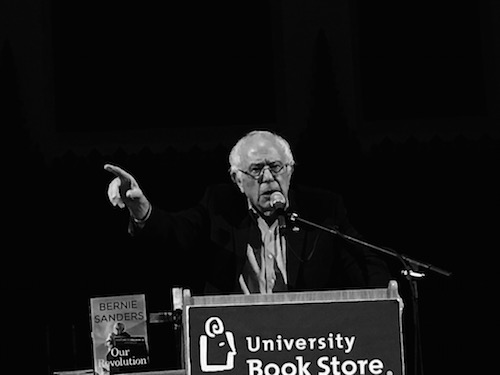

The audience was applauding Sanders and his wife, who had entered at the back of the church and were slowly making their way toward the front. Finally, Sanders took the podium and without any ado at all, just started talking. Little had gracefully hit most of her major points — she asked the audience to silence their phones, she reminded them that Sanders was in town thanks to University Book Store, which, at well over 100 years of age, is by far Seattle’s oldest independent bookstore — but Sanders didn’t seem at all interested in the ceremony of an introduction. He knew why he was there, the audience knew why he was there; why not dig in?

The moment was, fittingly, a microcosm of Sanders’s presidential campaign: little pomp and circumstance, an immediate dive into the issues, an adoring mass of humanity hanging on every word that left his mouth. Much of what Sanders said from the podium, in fact, was a callback to the rallies of his presidential campaign. He demanded debt-free college educations and single-payer health care. He called for money to be taken out of politics. He decried the conventional power structures that sustain an oligarchy.

But this was no greatest-hits reel; Sanders frequently mentioned current events. He bookended the evening with impassioned calls for citizens to stand with the Native Americans at Standing Rock. And his speech — delivered from notes written in longhand on yellow lined paper torn from a legal pad — was littered with references to “Mister Trump.” He began by demanding that the audience “never, never forget that Mister Trump got two million votes less than Secretary Clinton...he does not have a mandate,” Sanders announced.

In person, Sanders’s speeches have a quality that television or radio can’t quite convey. On YouTube, he can sometimes come across as too loud, almost atonal. But in the room, he imparts an uncommon aura of dignity and decency. The hundreds of people in the church, each holding a copy of Sanders’s new book Our Revolution: A Future to Believe In, were rapt; it seemed as though they would’ve happily sat through a talk that was twice as long.

And Sanders seemed to be enjoying himself. He likes explaining issues to people. He seems to enjoy talking about solutions to problems. And he’s been doing this for so long by now that he seems almost unflappable.

Almost.

There was one moment early in the talk when Sanders was discussing the general election, in which Donald Trump faced Secretary Hillary Clinton. Out of nowhere, a very loud, very deep voice broke like a thunderclap: “YOU WOULD’VE WON.” Maybe it was just the placement of the shout. Maybe it threw Sanders off his rhythm. Maybe he was considering whether or not to respond to the shouter. Maybe it was just my imagination. But it seemed like, for a single heartbeat, the room teetered precariously on that one intrusion before Sanders caught his balance and forged ahead like nothing happened.

If you believe with 100 percent certainty that Bernie Sanders would have won a general election contest against Donald Trump, I’m sorry to inform you that you are fooling yourself. He might have. He might not have. The truth is, nobody will ever know. You can point all you want to the polls showing Sanders ahead against Trump, but polls are inexact and polls measuring a hypothetical political matchup are less than worthless for a variety of reasons.

Sanders may have been a populist candidate, but he is in practice a pretty conventional politician who believes in rules and decency and the truth. Trump believes in none of those things, and none of us can imagine what sort of ghastly tricks he would have pulled against Sanders in the general election. We simply don’t know how the press would have behaved. We don’t know whether conservative voters would have responded to Sanders as a threat to freedom and democracy. You have your suspicions and I have mine. But you can’t know. Nobody can. Sanders certainly can’t, and that is a special weight that he will have to shoulder for the rest of his life.

Our Revolution is a book that must have been written very quickly. It had to have been composed, for the most part, in between the end of Sanders’s presidential campaign and the Democratic National Convention. We’re talking a matter of months — weeks, really — to put together a nearly 450-page book.

Unfortunately, it reads like a book that was written in weeks. The first half of Our Revolution begins promisingly enough, with the fascinating story of Sanders’s political life. From early races where he clocked in single-digit percentages of the total vote to his current reign as the longest-serving independent in the Senate, his career is unique in American politics. But the account of his presidential campaign is slapdash and poorly organized, and it carries none of the drama that his followers felt so passionately.

By the time the first half of the book draws to a close, all but the most avid Sanders fans will surely consider skimming. The section in which Sanders lists all the celebrities who supported his campaign (“Mark Ruffalo is not only ‘The Hulk.’ He is a strong environmentalist.”) is particularly insufferable. Sanders’s great strength is his authenticity, and great swaths of the first half of Our Revolution feel inauthentic, rushed, and perfunctory.

Thankfully, the second half of the book, in which Sanders outlines policy prescriptions, is exactly what Democrats need to read right now. The Democratic Party at this point in history feels especially rudderless; Sanders is the closest thing to an ideological leader that the party has, and the back half of Our Revolution is a blueprint for Democratic candidates to find success in the years to come.

As we are seeing in Trump’s first few weeks as president elect, all that populist bluster he vented during the campaign is working out to be nothing more than baseless tough talk. Further, if Trump continues to stock his cabinet with Goldman Sachs refugees, he’s likely to face a populist revolt of his own. Sanders’s actual populist policies represent a path forward for the Democratic Party, a way to head off Trump’s bloviation and challenge the trickle-down agenda of Speaker Paul Ryan, through which corporate taxes are reduced, regulations are demolished, and working class wages are kept artificially low.

Half-measures and centrism clearly don’t work for either party anymore; too many Americans feel as though their future is uncertain. Americans from both sides of the aisle agree that the time for polished, market-tested bromides has passed. Trump recognized those feelings and falsely presented economic challenges as the fault of immigrants and other nonwhite Americans, when in fact those challenges were caused by wealthy Americans like Trump. As Sanders repeats again and again in Our Revolution, America is the wealthiest nation in the history of the world and our wealthiest citizens keep getting wealthier as our poorest citizens keep getting poorer. It’s a simple matter of arithmetic to figure out where all the money’s going.

So, yes: Democrats need to run on single-payer health care and debt-free college education. Democrats need to pursue voting rights for all and criminal justice reform. Democrats must make climate change a priority. Some of those policies seem impossible, but remember: so did a $15 minimum wage not so long ago. Hell, Bernie Sanders’s campaign for the presidency seemed impossible not so long ago. Things change, and quickly. Without a plan, without goals to move toward, it’s easy to get lost. Sanders is the only high-profile Democrat with a clear vision for what must be done, and that’s what makes Our Revolution so important.

Last night, Sanders joked to the audience that “if you get bored halfway through” Our Revolution, you should “skip to the last chapter.” On several occasions during his talk, he suggested that the final chapter of the book, titled “Corporate Media and the Threat to Our Democracy” was the most important part of his book.

And it’s easy to see why. In it, Sanders cites a Media Matters post from December 2015 which revealed that ABC World News Tonight devoted 81 minutes to coverage of Donald Trump over the whole of 2015, while the same program could seemingly only spare twenty seconds — one third of one minute — to coverage of Sanders during the same year.

This is not just sour grapes. Sanders expresses disgust that it proved to be so difficult to get the media to cover important issues like poverty and low-income housing and income inequality. And he explains why this is, profiling the six corporations that control 90 percent of all mass media and listing all the different corporate assets they control. This won’t be new information to many readers, but Sanders’s passion will likely re-ignite a new wave of outrage.

One of the largest, most sustained applause breaks from last night’s reading — and there were many — came during the Q&A session, when University Book Store manager Pam Cady read an audience question asking if Sanders was going to run for president again in 2020.

Sanders, who is, let’s remember, a politician, sidestepped the question. But let’s be real, here: by the time the next election happens, he will be 79 years old. With the constitution and energy that Sanders displayed last night, he will very likely still be a vigorous force in the Senate in 2020, but it’s highly unlikely that our nation will be ready for its first octogenarian president anytime soon.

But the way that Sanders sidestepped the question is important. He didn’t make a cute joke or waffle with lawyerly language. Instead, he started talking about issues. He mentioned students protesting the pipeline at Standing Rock. He called for his followers to fight voter suppression at every turn. He asked people to get involved in politics on the local level.

He was pointing the audience toward the future, not the past. It’s likely that the next Democratic presidential candidate is going to be a younger, lesser-known politician than Sanders. But whoever they are, that candidate is very likely to be promoting ideas that are very close to the ideas that Bernie Sanders promoted throughout the 2016 election. His revolution is far from over.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound