Body-horror for every body

Scissors dropping out of a uterus, a head attached to its neck with just a green ribbon, cement poured down throats to keep the soul from escaping — these are but a few examples of what I think about when I think about body-horror, a genre in which the graphic metamorphosis or destruction of a body creates a viscerally disturbing experience for the reader. Myth and fairy tale, in their rawest iterations, are natural precedents for body-horror. And isn’t the body itself, so much a source for horror? On its own the body can mutate; or outside forces, like, oh, say, a deadly pandemic exacerbated by capitalism and climate change, can impose new, terrifying ways of trying to stay alive.

As a reader, I don’t seek out body-horror per se, yet the stories seem to find me anyway, as horrors of the body are wont to do. The nightmare ritual of cement poured down throats is from Mercè Rodoreda’s mythic novel Death in Spring (1986), more dystopian political fiction than horror. The precarious green ribbon comes both from Alvin Schwartz’s 1984 book of children’s tales In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories (his stories in turn often drawing from folk tale), and Carmen Maria Machado’s story “The Husband Stitch” in Her Body and Other Parties (2017), a collection that blends psychological realism with horror, fantasy, and science fiction.

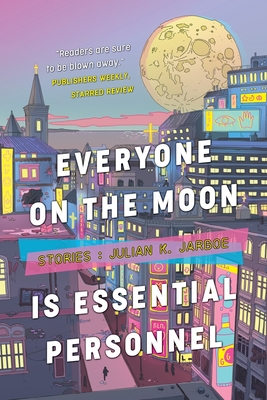

And the dreadful scissors are from “The Heavy Things” in Julian K. Jarboe’s similarly wide-ranging debut short story collection Everyone on the Moon Is Essential Personnel, which, I will tell you with some measure of relief, is not quite as grisly as I was girding myself for. This slim collection of only 222 pages draws on myth, fairy tale, apocalyptic visions of the future — capitalism and climate change gone further awry, and a necessary dose of dark humor.

Cutting, to feel release from absorbed abuse, features in “The Marks of Aegis,” the first story, a short-short: “I sliced along the planes of my skin and squeezed until everything on the inside that ought not to have been there was on the outside again.” The stuff of that expunged pain becomes, quite amorphously, a city the narrator calls Aegis.

All the people I had used had formed alliances with one another, built striking homes from the rough materials I’d left them with. Their culture may have started in filth but it had changed and grown. Their buildings floated and spun in slow orbit of one another. Every wall was a doorway and every stair a hall and every window a skylight or escape hatch depending on the rotation of the structure at given moment.

It’s a story that asks: what else can you do with scars but take pride in them?

That image from “The Marks of Aegis” is one of three moments of horror that stuck with me. The second I’ve already mentioned: as someone who has occasionally wanted to toss her own uterus into the sea, I could relate to “The Heavy Things,” in which the unnamed protagonist’s heavy period menstruates various sharp tools, but they cannot afford the hormone suppression that would make it stop. There’s an ironic humor here — rather than provide financial help, their mother is hopeful for a “nice knife set in time for Christmas,” highlighting a central theme of the collection, the rawness of trying to survive late-stage capitalism.

The third moment of horror occurs in one the most affecting stories of the collection. In “The Nothing Spots Where Nobody Wants to Stay,” tweens AJ and Jamie discover portals that allow them to zip from school grounds to strip malls and “other...nothing spots…where nobody wanted to stay for very long.”

AJ allows Jamie to aggressively fondle his “sizable tits” not because it is enjoyable, but because Jamie is AJ’s only friend. And perhaps also because Jamie’s father died in 9/11, and for AJ, the groping is “a welcome relief from gravity.” It’s a double-horror of allowing a violation of body part that, for AJ, is itself a horror. We flash forward to AJ’s first thought after top surgery, fifteen years later: “well, now I’ll have to rely on charm alone.” It is an incredibly lonely story.

Tonally, the sixteen stories taken together feel quite variegated. “The Marks of Aegis” is mythically sparse, while “We Did Not Know We Were Giants,” drawing from the Book of Job and the writings of John Muir, is mythically grand. “The Seed and the Stone” is a dreamy fairy tale. These stories have a certain timeless quality about them whereas many of the other stories feature a contemporary “voice-y” aesthetic that sound very much like life now.

“My Noise Will Keep the Record” attempts to bridge both modes. It begins like a fairy tale, but then quickly introduces a near-future dystopia: our “increasingly cybertronic” narrator must sell off body parts to make ends meet. They have taken too much sick time and will lose their contract job, where they digest sound files extracted from personal assistant devices strapped around “full-flesh” people like dog collars in order to refine the sales algorithm. Their supervisor makes clear there is no recourse.

But the irony is that this supervisor once tried to bond with them because they were “diversity hires.” And this highlights another intriguing thread in the book: how inadequate attempts at political correctness foment frustration, how we need more than the flimsy band-aids barely holding on to deeper wounds, and how much more work must be done in order to care for each other. The gradual departure of body parts reminds me of another dystopian story of medical horrors, Ninni Holmqvist’s novel The Unit (2006), in which all childless adults over the age of 50 are deemed dispensable and sent off to a resort-like prison to have their organs gradually harvested.

Speaking of dispensability, in the novella “Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel,” the unemployed protagonist Sebastian laments that “all the shitty jobs are headed to space,” which means he too must go to the moon to work for a big tech company that resembles Amazon. The inevitability of lunar work forces Sebastian to decide whether to express his love for his friend Yonatan. He must also contend with leaving his mother, whom he is reluctant to characterize as abusive — yet he can imagine her throwing her slippers at his face in anger at the decision to go to the moon, yelling that she made him and can unmake him. It takes a shift into his sister’s perspective to get the full picture.

Jarboe isn’t afraid to experiment. The novella features a slew of imaginative stylings, including a long “personality assessment” that veers toward the Dada-esque. And yet through this wild experimentation and skewering of big tech, what is ultimately moving and rewarding is Jarboe’s exploration of Sebastian’s friendship with Yonatan and his anguished love for his mother.

Balancing the heartbreaking loneliness of some of these stories is the irreverent, Kafka-inspired “I Am a Beautiful Bug!” Our hero has longed to be a bug and has the surgery done in Canada, easy-peasy and on the cheap. But bureaucratic horrors await afterwards at the border, where identification papers are seized and bank accounts frozen.

Further horrors unfold at the DMV, where the Director of Diversity and Inclusion attempts to quell the protagonist’s protests using the techniques of PR damage control. Then the director informs the protagonist that, actually, Kafka never meant the bug to be literal. “I am not a metaphor,” our protagonist declares, even as the Director continues to mansplain.

This is a slim book with lots going on and with shifts in tone that some may find jarring. Mavis Gallant once expressed horror at someone reading one of her story collections all the way through in rapid succession. Her preferred method would be to read one story, then set the book down a while, read something else, come back. This might be a good approach for Everyone On the Moon Is Essential Personnel, not out of a fear of the stories running together, but to allow these textured stories and their raw messages the mental space to take hold.

Anca L. Szilágyi is the author of the novel Daughters of the Air, published by Lanternfish Press in December 2017. Her work appears in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Electric Literature, Gastronomica, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of awards from Artist Trust and 4Culture, among others.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound