Destroyer of worlds

If you were to ask me to identify the birthdate of the modern world, my response would be immediate: the planet changed forever on the day of the first atomic bomb explosion. And that moment, at least in retrospect, has an air of destiny about it. Perhaps that's why the Manhattan Project, and America's desperate rush to split the atom, has been the subject of so many novels and conspiracy theories and films and comics. Those brilliant men were the midwives of a new world, and their science was so advanced, and so desperate, that it's hard not to think of them as modern wizards.

Atomic power was seen by those in power as the only way to end World War II, to eliminate the virus that had swept the planet. The monstrosity that Hitler unleashed on the world demanded an even larger power to stop it. Try to tell me that doesn't sound like a curse in a fairy tale, or a medieval story of magic and sacrifice — I'll laugh in your face if you do.

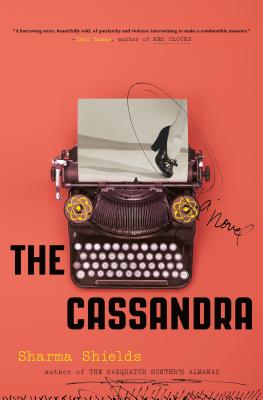

Spokane author Sharma Shields's second novel, The Cassandra, is about a forgotten aspect of the Manhattan Project — the rush to process plutonium at the Hanford Research Center, right here in Washington state. The book stars Mildred Groves, a young woman who leaves her life behind to work in the secretarial pool at Hanford. There, in rugged camps on the shores of the Columbia River, Mildred is a witness to the harnessing of nuclear power.

But because no story about the atomic race can ever truly be without some supernatural element, Shields has given a power — or more aptly, a curse — to Mildred: she can see visions of the future. She's a modern Cassandra. And just like the Cassandra of myth, Mildred is destined for a world of trouble.

At first, Mildred is a charming puzzle for the reader to solve. The responses she fills out in her Hanford job application raise some concerns with the straightforward military men assigned to hire the 50,000 people that Hanford's founding demands. To convince her prospective employers that she has relevant job experience, Mildred writes, "I have imagined myself in a giant number of jobs, some of them impossible, some of them quite easy, and in my imaginings I've always done well by them, impossible or no."

Anyone who's applied for a job they're vastly underqualified for can relate to this — the "giant number," in particular, is a nice touch of hyperbole. But the first sign that Mildred is more than just preternaturally confident comes lower down on the application:

I only wish to say how confident I am that I will be the best fit for this position. I have seen myself there as clear as day. I dream about it. I know for a fact that you will hire me. I will not let you down.

She's not lying. She's just reporting what she's seen. Her interviewer interprets is as "A bit of confidence" and therefore "a good thing." But Mildred explains to the reader, "I knew better than to tell him the truth, that I had dreamed about Hanford, that I had seen myself there...He would hire me because I had envisioned it, and my visions always came true in one form or another."

Her visions aren't always as clear as she makes them sound. She suffers from fits of sleepwalking and fugue states; she has dreamlike visions of birds and wolves. She can see the horrors that are coming, once the plutonium from Hanford makes its way south to the bomb-making facilities in New Mexico, but the breadth and scope of what she sees are beyond her understanding. She's from the old world. She can't understand the new world that is around the corner.

Mildred is running from a family that relies on her even as they mercilessly abuse and demean her. The freedom she finds at Hanford is liberating, but she's also terribly unequipped for adult life. She has no sense of what to do when a man comes on to her, for instance, and the scene at Hanford — with its relentless drive to bring the future to life sooner than expected — is practically feral just beneath the surface. Everyone is on edge and the men are more monstrous than usual. To call Hanford a powderkeg would be an exponential kind of understatement.

Anyone who's seen Hanford understands that the land there is haunted. (One Google reviewer of the Hanford Site snarks that they had a great time on their tour, but "The only downside is the acute radiation poisoning and the local mutated wolves.") It's haunted by memory and by history and by the sense that the earth was opened up and something bad was unleashed and can never be returned to where it belongs. In that respect, The Cassandra is a ghost story, only the ghosts don't yet realize that they're dead at the time of the story.

Because we are all struggling with a depressing and frightening world, I want to be clear for any readers who may be emotionally tender: this is a dark book. But of course, it would have to be; you can't really write about the dropping of the atomic bomb without trying to reckon with the human cost. Those who enjoyed the audacity and the excitement of Shields's first novel, The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac, will not see much of a family resemblance in The Cassandra. The writing is just as sharp — sharper, even. And Shields's imagination is just as lofty as it's always been. But she's struggling with a great human tragedy in this book, and Mildred carries that burden on her back. She's a witness of the birth of our modern world, and there's no way she can go unpunished for what she's seen.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound