Dredding every minute of it

"A good hero is hard to beat, and a good villain is hard to beat, so why not combine them?"

- John Wagner

In a galaxy far, far away…

When I was growing up in rural Bedfordshire in the Eighties, there were fairly limited options for sci-fi action fans to get their fix. On TV, there were three — then four — channels that might show the odd Star Trek or Doctor Who episode. Kubrick’s classic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ aired every New Year’s Day. There were computer games of course — the rivalry between ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64 owners raged long and hard on the playgrounds of England, with truces only to unite against the posh kids and their BBC B Microcomputers — but blocky 8 bit graphics didn’t really give much of a narrative experience.

…and then there were comics. Wandering into a newsagent’s, we’d browse an assortment of weekly-published anthology comics with five or six separate stories. They were disposable, usually printed in black and white on low-quality, flimsy paper that was sometimes disparagingly described as bog roll (translation: toilet paper). Alongside the comedy standbys like The Beano and The Dandy, there was The New Eagle, a relaunch of a comic book featuring hero Dan Dare, a square-jawed 1950’s space adventurer, as well as a couple of media tie-in comics like Look-In, which mixed articles with comic books of popular shows. There was even a Star Wars spin-off comic series, repackaged monthly Marvel US stories chunked for the British market.

But if you really wanted the hard stuff, you’d pick up 2000 AD, featuring Judge Dredd.

2000 AD was conceived in 1976 with the intention of cashing-in on a surge of renewed science fiction interest that coincided with the anticipated release of the first Star Wars movie. I can’t claim to have smeared my chubby toddler hands on the crisp, freshly-inked inaugural issue of 2000 AD just after it landed on shelves in February 1977. Instead, later, a Judge Dredd Annual somehow fell into my possession. I suppose my parents might have bought it for me off the newsstand, but it seems far more likely that I scored it second-hand with pocket money while scrounging at a car boot sale (translation: yard sale). Either way, I have clear memories of obsessively pouring over a tattered copy of the 1981 Annual. Within its pages, a bolt of lightning: ‘Bank Raid’, the first Judge Dredd story ever created, written by the visionary John Wagner with art by the incomparable Carlos Ezquerra. I was instantly hooked.

I had catching up to do. 2000 AD had launched its first issue in 1977, promoting hero Dan Dare as its star attraction — though instead of the 1950’s stiff upper-lip RAF fighter pilot transposed to outer space in ‘The Eagle’ and ‘The New Eagle’, this late-1970’s incarnation was reinvented as “Dan Dare: Space Hyper-Hero,” Ziggy Stardust-style, complete with psychedelic prog-rock style artwork.

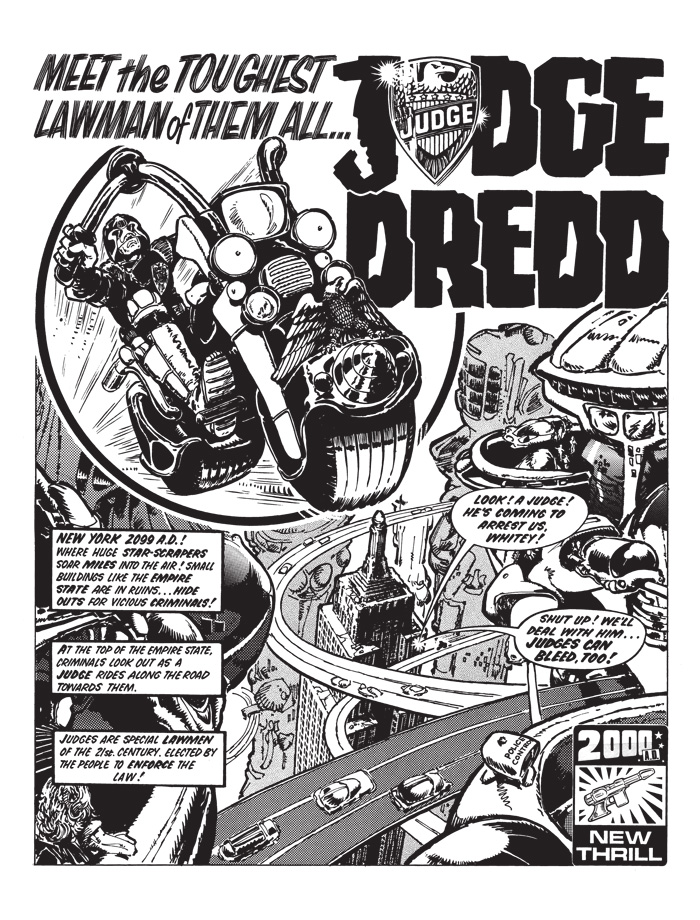

Then, Judge Dredd was introduced in Prog 2 of 2000 AD. (Issue 2, or ‘Programme’ 2 was shortened to ‘Prog 2’ which sounded computerish and more in keeping with 2000 AD’s futuristic theme). Unlike the reinvented Dan Dare, there was nothing prog-rock about Judge Dredd: a motorcycle cop clad in black leather, quick to dispense violence in the name of “The Law” and empowered to be “Judge, Jury and Executioner”. The New York City of 2099 he inhabits is no less fearsome, with its out of control criminal gangs squatting in the decayed hulk of the Empire State Building, itself dwarfed by imposing “Starscrapers”. The gritty aesthetic was less hippy, more punk. Judge Dredd would knock Dan Dare from his preeminent sci-fi icon pedestal, establish ‘Dredd’ as a buzzword for authoritarian policing, and herald a future for 2000 AD that would extend far beyond the year of its title.

The original conception for Dredd had been as an uncompromising cop in a not-too distant future, very much in the mold of the Dirty Harry-style secret agent Dredger in the UK comic Action. Action was a comic started in February 1976 that had proved extremely popular with its audience due to its combination of outlandish violence and a distinct anti-authoritarian leaning, until a media protest campaign by a major newsagent chain led to a boycott of its parent company and shut it down — at least temporarily. Action’s October 1976 issue was pulped before publication, and the comic would re-emerge in November in a meeker, less subversive form.

Editor Pat Mills and writer John Wagner had worked on Action and sought to both repeat its successes and avoid its pitfalls in their new comic 2000 AD, this time hopeful that the science fiction setting would enable them to present anarchic content under the guise of fantasy. Joining Mills and Wagner was Carlos Ezquerra, a Spanish artist who had lived under Franco’s regime. Ezquerra’s fascist references for Dredd were clear — he had based Dredd’s helmet on an executioner's hood and bedecked his uniforms and equipment with an eagle insignia swiped from a fascist-era coin. To drive the point home, he added reflections in Dredd’s visor reminiscent of SS lightning bolts. In total, Dredd dripped with imagery of violence and totalitarianism — not a comforting figure.

By making Dredd into a character who was basically a Nazi, the creators were able to have all the thrills of the Dirty Harry-style extreme cops while pushing further into the realm of near-parody, creating rich opportunities for satire and black humor. This dark satire was particularly well-timed, since the Britain of the early 1980’s was plagued by high unemployment, riots and striking workers who faced a heavy-handed police response. All great stuff for a kids’ comic, right? I sure thought so.

‘Bank Raid,’ in addition to being the first Dredd story I read in the 1981 Annual, was the first attempt at a story using the new Judge Dredd character by Wagner and Ezquerra. But it was thought too violent to serve as his debut in 1977 and it was shelved for four years. “Judge Whitey” took its place: scripted by freelancer Peter Harris, “Judge Whitey” was heavily rewritten by Mills. The artwork is similarly a chimera — young up-and-coming artist Mike McMahon drew it in the style of Ezquerra, and big chunks of Ezquerra’s art from ‘Bank Raid’ are pasted in. Outraged by this, Ezquerra would refuse to draw Dredd again for many years, and Wagner left the editorial team to become a freelancer, but Dredd’s tumultuous birth was complete and he was an instant hit — he would appear in every issue of 2000 AD from that point on.

Following Judge Dredd’s debut, several important elements would change: Starscrapers became Mega-Blocks and New York became Mega-City One, an isolated city-state under the totalitarian rule of Justice Department and the Judges. A vestigial police force seen assisting Dredd in early stories would quickly disappear when the editors decided that the Judges would be the only law in the city.

One of Ezquerra’s big contributions to Dredd proved to be vital to the strip’s longevity: instead of conventional towerblocks and tenements, his art, later pasted into “Judge Whitey”, showed a far-future city of strange bulbous towers and elevated roadways, creating a setting stranger and more exotic than future New York. The far-future setting served Judge Dredd and 2000 AD well over the years, acting as a springboard for all kinds of science fiction-themed stories and building up a menagerie of aliens, mutants, psychics and visitors from other times and dimensions, which all somehow managed to be integrated seamlessly and have a distinctive Judge Dredd spin to them.

This magpie tendency even extended across genres: When Dredd wanders beyond the borders of Mega-City One into the vast wasteland of the Cursed Earth, the stories become futuristic Westerns. The genre shifts again to Horror with the introduction of Judge Death, Dredd’s twisted mirror image from another dimension, where life itself has been declared a crime.

The one constant is Dredd. Imbued with an unlimited reserve of stoicism and not much given to change himself, Dredd is a perfect foil for the chaotic ever-changing world around him.

The one constant is Dredd. Imbued with an unlimited reserve of stoicism and not much given to change himself, Dredd is a perfect foil for the chaotic ever-changing world around him.

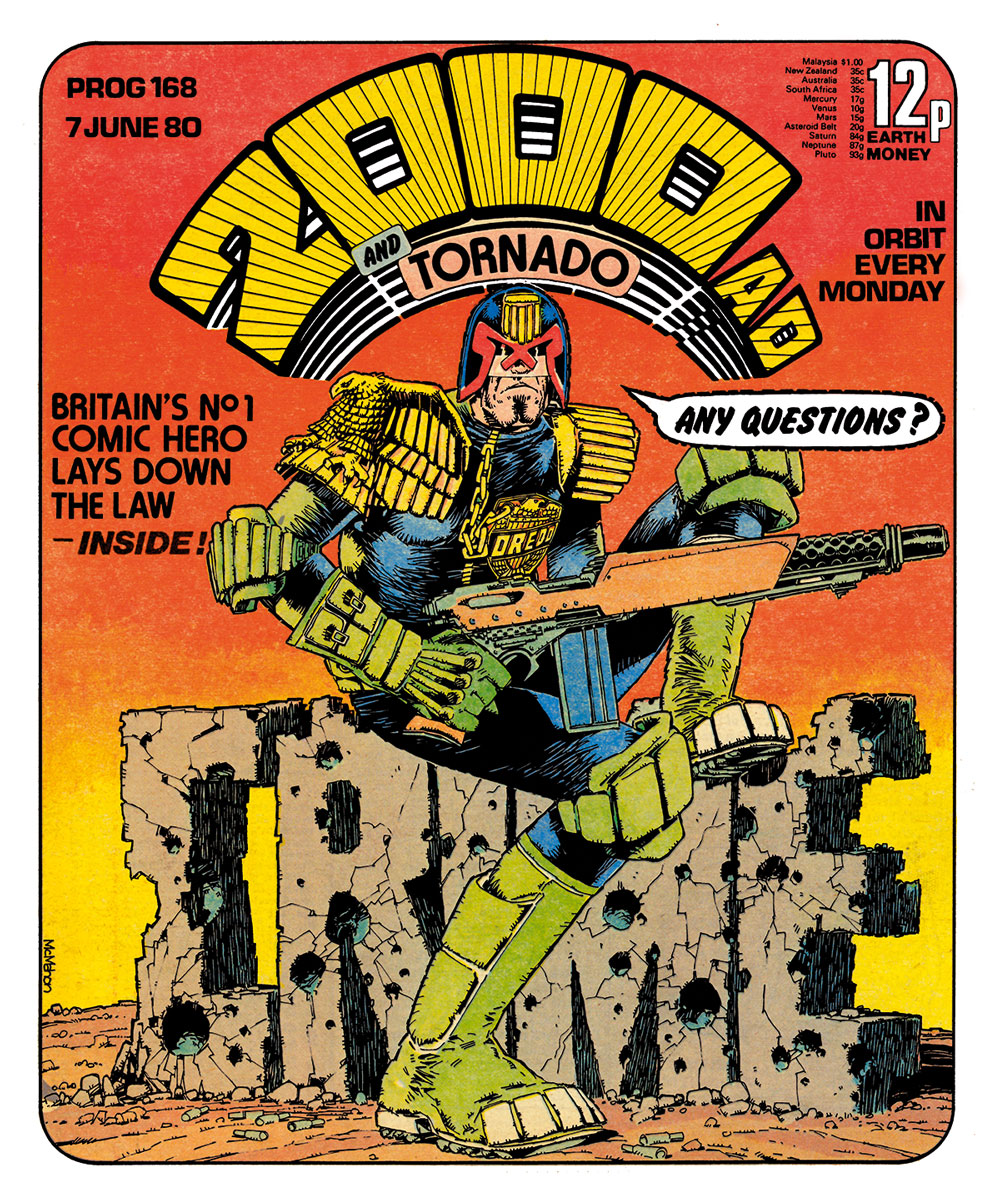

In 1980, John Wagner returned and began writing with Alan Grant, launching one of the most iconic phases for the character: The Wagner/Grant stories consist mostly of Dredd reacting in a deadpan manner to various crazy consumer fads and city-destroying disasters and supplying the odd quip, beating or shooting as prescribed. This became a classic, repeated formula.

I started reading 2000 AD not long afterwards — first as a monthly anthology of reprints, and then the weekly Prog itself. Though I enjoyed Judge Dredd it was probably not my favorite; as a child of hippies I gravitated towards the Celtic mythology-tinged ‘Slaine’ or the anarchism of ‘Nemesis the Warlock’ — both the work of Pat Mills, whose left-wing leanings would become more overt as time went on — or the anti-war sentiments of Milligan and Ewin’s Bad Company. All of those are excellent, of course, 2000 AD of that era rarely ran a bad strip, but they also avoided the moral wrestling I would experience reading Dredd’s adventures and rooting for an authoritarian bastard.

Still, Judge Dredd remained the star of the Prog — the only story that would run consistently week to week, frequently the cover star, usually the best story in it, especially if Wagner was writing. Even as 2000 AD comic had an infamous dip in quality in the 1990’s, Wagner was still going strong with the mega-epic ‘Necropolis’, one of the stronger stories featuring the undead Dark Judges. But change was coming, and after symbolically killing off his character in that story Wagner would move on to other projects, leaving Judge Dredd in the hands of up-and-coming writers like Garth Ennis, Grant Morrison, John Smith, and Mark Millar.

Growing up Dredd

By 1990 the British comics industry had moved on. Most of 2000 AD’s newsstand peers had died off, and its readership had aged and diversified: the market for Dredd and his fellow characters was no longer pre-teen boys. Some of the repetitive notions from the comic’s origins were wearing thin. Stories that would seem to cheer on the actions of a violent fascist cop under the veil of satire in particular began to seem questionable. Writers like Morrison and Millar would take the action to jokey, violent extremes, but that effect failed to make it feel any fresher.

At the same time, 2000 AD was facing competition from hipper, magazine-like publications such as Revolver, Deadline — home of Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett’s irreverent ‘Tank Girl’, and Toxic!, a short lived attempt by a number of 2000 AD’s creators, including Wagner, to launch a creator-owned weekly anthology comic. Competition would also come from the US, where DC’s Vertigo imprint would offer similar creator-friendly deals to some of 2000 AD’s top talent. I wound up reading a mix of these, and Dark Horse comics, during my teenager and university years. They had a certain cachet with hipper, more socially outgoing groups who would do things like: go to gigs, or going out drinking in mixed gender groups rather than hanging out in their bedrooms playing Xenon II and watching Total Recall for the ninth time.

As it turned out, Wagner was not quite done with Judge Dredd — much as he and Mills had shepherded 2000 AD into the world, he would be involved with the creation of a second new anthology comic in the 1990s, one that would address many of the issues facing 2000 AD at the time — a spin-off comic that used a larger page count to tell deeper, more sophisticated stories set in the world of Dredd, even with some stories unconnected from Judge Dredd himself.

The first issue of the Judge Dredd: the Megazine in 1990 led with Part 1 of a story titled “America”, focusing on the life of America Jara, democracy activist in the solidly undemocratic Mega-CIty One. Though we had before seen stories where Dredd crushes down the hopes and dreams of Mega-City One's citizens (often in the name of combating the Democracy movement), this was something different: Dredd is on the periphery of the story, and unquestionably the villain of the piece, with not even a shred of admiring anti-heroism. The story was conceived as a single whole and crossed several years rather than being in continuity. It was arguably the most sophisticated Judge Dredd story of its time.

It is interesting to note that Dredd as a character wasn’t changed to accomplish this. In these stories, Dredd doesn’t turn evil or become more extreme, we’re just seeing him from another angle. The first-person captions from the opening episode are a kind of statement of Dredd’s worldview dismissing the idea of rights at the expense of order. Although the quote “Justice has a price, the price is freedom” could have come from any Judge Dredd story, “America” makes the horror of that idea clear, just in case anyone thought the world of the Judges was meant to serve as an aspirational ideal.

Everything that made me uncomfortable as the character as a kid was brought to the fore, bringing with it a brutal honesty about the implications of the premise, and in doing this Wagner managed to make Dredd and his world much deeper and more interesting.

The Long Arc of the Law

2000 AD bounced back from the dark days of the 1990s, of course, and like many readers I rejoined the fold to find Judge Dredd richer and more interesting than when I’d left — and also, aged. One crucial aspect in which the world of Judge Dredd differs from the Marvel or DC universes is that time actually flows there — Dredd himself is now in his 70’s while most American superheros have remained locked at the same age they were when they were created. It’s even been suggested that John Wagner, still the primary writer on Judge Dredd strips, might eventually allow the inevitable to happen — Dredd’s luck running out, his reflexes slowing with age, perhaps a random street punk managing to put a fatal bullet in him.

Still, raw economic considerations make that somewhat unlikely … so apparently in the year 2137, 70 is to be the new 50. A Dredd that ages does, however, mature and deepen. As the Dredd of 1990’s “America” is an older, more beaten-down Dredd than in the early 1970’s ‘Case Files,’ Dredd in 2015 has been changed by “America”, pushing him to the edge of villainy. In recent stories like “Origins” and “Tour of Duty” we see him begin to question his uncompromising stance. “Day of Chaos”, the story that most defined the current ‘status quo’ of Dredd’s universe, sees the consequences of that stance come crashing home with disastrous results.

It’s with wonder that I reflect that all this rich storytelling stems from a throwaway character, afterthought to main attraction cover hero Dan Dare, created for a comic named for the year 2000 — a year thought to be so representatively modern and sufficiently far into the future that it was thought it would surely remain a future context for as long as the comic could possibly endure.

Next year will be the 40 year-anniversary of the debut of Judge Dredd, and Judge Dredd himself shows no sign of winding down anytime soon. Judge Dredd stories have endured, indeed with several ongoing storylines, vehicles and mediums — as Dredd stories now fill multiple comics, films and audioplays. The Dredd universe has expanded exponentially, giving birth to characters that exist in a Dredd universe without ever even coming into contact with Judge Dredd himself.

That’s how I, having grown up with Judge Dredd, ended up writing it myself. I began by writing Future Shocks, often a writers beginning step to writing for 2000 AD, these are short self contained science fiction stories with a twist. Once I had sold a few of those (as well as Terror Tales, the horror equivalent) I looked over to the Judge Dredd Megazine, where they ran “Tales from the Black Museum” as similar twist tales from Justice Department's crime files. This let me draw on the ‘Cursed Earth’, the ‘Apocalypse War', and other classic Dredd tales as seeds for stories, and it wasn’t that much of a leap from there to writing 'Samizdat Squad', a series of my own set in Dredd’s world and eventually writing the big guy himself.

As a writer, Dredd’s appeal is much the same as it is as a reader: the hyped-up setting, the bizarre situations and opportunities for black humor, the visceral thrill of the action mixed with the cerebral thrills of the bleak social commentary. At its best, Judge Dredd combines all these in shifting proportions, allowing the telling of a broad range of different stories, and so you want to get that right.

The contradictions I was aware of as a kid are still there of course, and can loom troublingly when real world events mirror what’s on the page. A story about the Judges beating down a riot takes on new weight when you are watching police dressed in something not unlike Dredd’s movie uniform tear gassing protesters. Violence and authoritarianism are such a deep part of the character that, done wrong, his stories could be an endorsement of all that is terrible in the world.

There’s no real answer to that except to meet it head on, as Wagner did with 'America', and make the story a mirror rather than an endorsement. Like the best science fiction, it shifts to capture a reflection of the present, spinning threads of recognition of our own reality within an outrageously foreign context.

That’s needed as much now as it was in 1977.

British comics writer living in the Northwest.

Follow Arthur Wyatt on Twitter: @arthurwyatt

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound