Five reviews in different styles of Rufi Thorpe's brilliant new novel

THE NEWSPAPER STYLE REVIEW

Rufi Thorpe's startling sophomore release, Dear Fang, With Love, which is being released tomorrow, May 24th, brings to mind Roger Ebert's edict about films: they aren't what they're about, but how they're about them.

Not that the what here isn't compelling: a teenage girl, Vera, and her father, Lucas, and a trip they take to Vilnius in Lithuania to trace his familial history, and to get away, in some sense, from dealing with a recent diagnosis of Vera's bi-polar disorder. Her parents are not together. Lucas was not around for the first seven years of her life, and now is trying to make up for it.

"We see each other on the weekend, and it's fine. You rent whatever movie I want, we order whatever food I want, great, fine. But sometimes you are so desperate for me to like you that it makes me annoyed. You're like a dog begging for attention. It disgusts me. You are honestly the last person in the world I want to talk to right now."

It was like I had woken to discover I was at the top of a Ferris wheel, the car bobbing over empty space. Vera could do that to me, pull the rug out from under me. It was always a struggle not to let her know how badly it hurt.

Vera is over-sharp, her wit and acuity too present for her own control. Her saturation is turned straight up. For someone with colorful intensity, she is so unapologetically appealing, someone you root for and see the struggle of the muscle under the skin. She's the kind of teenager that you know, if she can just make it past being a teenager, if she can just make it past being a young woman, she'll going to be an amazing adult. She'll probably be a writer.

But it's the language, writing, and characterization that spring the novel from a well-told-tale into one of the finest releases of 2016, and one that hopefully pivots the Sauron's eye of public attention squarely to its pages. Plainly: Thorpe is a major talent, and reading her work will bring to mind other writers who deftly control their universes with such clarity and acuity, like Donna Tartt or Ann Patchett.

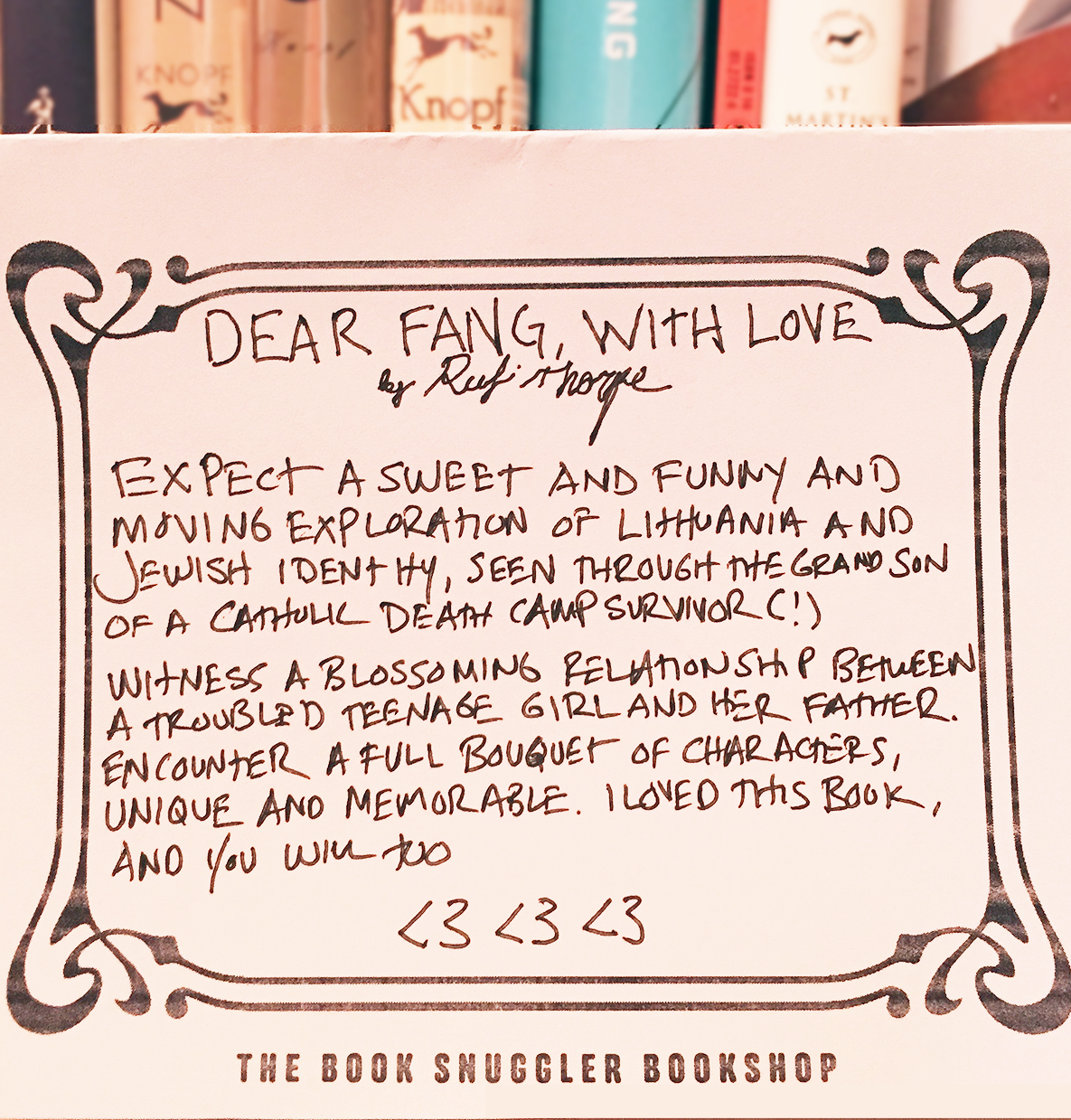

THE INDIE BOOKSTORE SHELF TALKER STYLE REVIEW

THE STORIED OLD REVIEW PUBLICATION STYLE REVIEW

When you read Elizabeth Bishop's query "Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?" you can't help but think the troubles of travel: the lines, the hours sitting bored on some conveyance, the hotel check-ins and small inhumanities we suffer in order to move about the world. Or the very worst possibility: becoming sick somewhere that is not your home, suffering in a strange bed bereft of home's talismans and comforts.

I like to think of Bishop's travel from America to Brazil, where she met her lover and partner Lota de Macedo Soares, whom she dedicated the book that bore the title of the poem from which that quote is extracted: Questions of Travel. And there, in what was first a travel destination but then became her home, I think of her not going on trips, but of staying instead, sitting on a tropical veranda, in a concrete modernist house, on a chair like an exaggerated and extruded Eames (Brazillian modernism was always so much bigger, so much more explosive and bold), her notebook open on her table, an iced drink nearby, dressed in cool linens.

But that's not the whole truth. Staying at home you also see that night where Bishop's sobriety was undone, and after emptying every bottle in the house she stumbled to the dressing table and drank perfume. Oh the gulf between those visions! Each as true as the other, neither containing the whole of her, just actions and moments.

Travel is central to both the plot of Rufi Thorpe's Dear Fang, With Love, and to understanding it. The narrator, Lucas (the novel is partly epistolary, and we also see from the inside of his daughter Vera's head through her writing to the titular Fang, her boyfriend) has arranged a trip for his daughter and himself, and we join them, there, in Lithuania. But we also travel with Lucas into a late-onset adulthood, despite his efforts to hold it at bay, his over-smart rationalizing of whatever position he happens to be facing at the given moment.

Lucas is a drunk stumbling about the house of his life. He cares, which is his biggest mode of conveyance, but that runs counter to his heart-felt desire to appear cool and relevant. Like many modern proto-American men of a certain proclivities, he is passive, unwilling to make hard choices that will force him to engage. Stick around, reader. You're about to watch him wake up to that fact, and when he comes to face his dressing table, we find out if he, in fact, drinks his perfume.

In Vilnius we travel into the past on tours of the city, and into history. The tour the characters join is mostly made of writers, mostly Jewish, learning of the Shoah in Lithuania. There is Susan, the writer, with whom Lucas shares a flirtation despite her being some twenty years his senior (and "There was something about the woman that reminded me of my mother, so probably sleeping with her would trigger some kind of Oedipal curse and should be avoided at all cost"), and Judith, the still older woman who becomes a surrogate grandmother to the questioning Vera.

Lucas' own grandmother Sylvia was a Catholic woman in the Stutthof concentration camp, who escaped through the curious actions of a guard, and this story became one of great legend in his family. There are relatives in Vilnius, he finds out. This is a book of people, and as such, it is wonderfully wrought. It is not unlike a gift Lucas buys for Vera as a present: "I didn't like the pendants, just one big gob of amber on a chain, and I finally settled on what I thought was the prettiest thing in the store: a necklace of perfectly polished, large round amber beads the ranged from the lightest, palest honey all the way to the darkest, pitchy red-black, perfectly arranged like a rainbow. I could picture it on Vera's neck." Imagine each of those beads of amber a character in the book, all them distinct from the rest as if the light they refract was born of different sources.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? But, if we had, we'd never have seen that necklace, nor Lucas buying it, nor his gifting of it. We should travel. Even Bishop was arguing for it, of course, in her questioning: "Is it lack of imagination that makes us come / to imagined places, not just stay at home?" Not in Rufi Thorpe's case. Here is imagination enough for us all.

THE ONLINE MERCHANT STYLE REVIEW

by booksnuggler23 on May 21, 2016

Format: Hardcover

Sometimes you read a book so good that you cannot even imagine other books for a while. During the time you're in its spell, it's like being in love. How could you think of anyone else? Maybe another is attractive, and full of life, and maybe even you abstractly want them, but your heart beats a spotlight in one direction. There is only one you want to illuminate.

Not that I want you picturing me in bed smoking beside a copy of this book, Rufi Thorpe's "Dear Fang, With Love", but like being in love, I think I'm gonna blab about it to everybody I know for the time being. And unlike a lover, I doubt the book is going to do something mean because it thinks I'm too needy or not living up to my potential or that I want different things than it. I mean, books want to be read and I want to read them, so boom, simpatico needs.

This is a book about women, told mostly by a man. A man raised by a single woman, whose grandmother was the 'triarch (both ma- and pa-) of the family. There are few men in his life, and none with authority of any kind, but although he has moments of masculine questioning, this is not the point of the book, just the country it takes place in. Well, I mean, it takes place in Lithuania, but you get what I mean.

You want poor Lucas to do well, because the stakes are high. He's in a warming-but-still-cool relationship with his ex, Vera's mother, Katya (who is Russian as all get-out), and he's trying so hard to be a good dad to his daughter after years of neglecting her. Ignoring her, maybe is better. Pretending she didn't exist, really.

But Vera is fighting her own demons, and there is the very real confusion and uncertainty you find when it comes to human health (ever noticed how clear-cut diagnosis are in most fiction and television, but how ambiguous and confusing and mind-melting they are in real life?). She's on serious drugs after having an episode, and processing that diagnosis of her bi-polar disorder is a big part of this work.

Look, truth is, I want to keep talking about it, but I'm going to stop myself because I'm going to start reading it again. It's laying here against my thigh calling to me. Let me just leave you with this: buy it, buy it, buy it, buy it, buy it. And don't forget to buy it.

Was this review helpful to you? report abuse

THE TWEETSTORM STYLE REVIEW

😍 This is from @rufithorpe's latest. Good goddamn. She gets into something real here. pic.twitter.com/lpkaZu2DVq

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

In fact, I gotta do this. Hang tight. Mute me if you gotta. It's time for a (drum roll):

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

ᴛᴡᴇᴇᴛ ꜱᴛᴏʀᴍ 🌩

Let's call it:

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

(••)

<) )╯GENDER ROLES!

/ \

(••)

( (> WHO

/ \

(•_•)

<) )> NEEDS 'EM?

/ \

(Do people title their tweet storms? Am I doing it wrong? 🤔)

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

This is a book that is about gender roles in a way that most books about gender roles aren't.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

That is, the women in this book are fierce like real women who face adversity. Not like tender-tough characters so common in modern fiction.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

One faces the anniversary of a trauma with a yearly cake. Fuck you, not wanting to deal with shit. We deal with shit here. Right in its face

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

The men in the book, like Lucas who was talking above, are incapable of making choices.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

One dude nearly ruins an evening in the book with passive-aggressive racism and anti-Semitism.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

It's the type of near-racism and near-anti-semitism that is the mark of the modern bigot, worried with "political correctness".

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

They always withhold a bit of their venom, so that if you call them on it, then can say "Whoa man, I wasn't saying that. I'm not a bigot."

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

It's gaslighting via refusing to have the courage of your convictions.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

And this happens in a city where a synagogue dating to the 1630s was destroyed by Soviets after the war!!

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

That character was so real and so vivid and so evocative of a kind of modern masculinity, where men complain about lack of manliness.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

But only in safe forums where they won't be checked. And if they are checked they put on anime avatars and swarm the woman who call them out

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

They weep over the death of this masculine ideal (hint: it was always a fiction, just like the feminine ideal, people just ain't like that).

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

The irony being that "real men" of the type they idolize would spend ZERO time complaining about how people treated them.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

The ideal of that type of masculinity is action over thought. It is seizing your own destiny and dealing with shit.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Exactly like the women in @rufithorpe's book do. While the men make themselves powerless (with one exception:

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Fang, the guy in the title, who is a young Samoan Mormon, and who is comfortable taking action, and is Lucas' daughter's boyfriend).

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

In this way, the book could be called feminist, but it's better maybe to call it of feminism. It's first a good story with good characters.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

I doubt @rufithorpe theorized a way to stuff feminist ideology into the pages, although the anime men would probably think so.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

What she has done, as just one part of a book about much more than just this thing, is illuminate a myriad of types of modern men.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Men who are faced with independent women and figuring out what this means to them. Men who are learning to act.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Men who are lost, but have just found a map and will struggle to get there, perhaps.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Men, who most importantly, love women and love the company of women. Who are more comfortable with women than they are with other men.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Again, this is a small part of what @rufithorpe has done here. This is a book more about women than this. But by looking at this small thing

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

I wanted to show how big this book actually is. How much she gets at that is true. I could rant like this about other parts of the book, too

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

But I won't. Read it yourself and decide. Really. Read it.

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

</rant>

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

💪🏻

Oh, one more thing. Confidential to Susan: you're my hero. Stand tall. 😘

— The Book Snuggler (@booksnuggler) May 22, 2016

Martin is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He's a novelist (his first, California Four O'Clock, was published in 2015 by a successful Kickstarter campaign). He designs websites, apps, and other things for a living.

Follow Martin McClellan on Twitter: @hellbox

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound