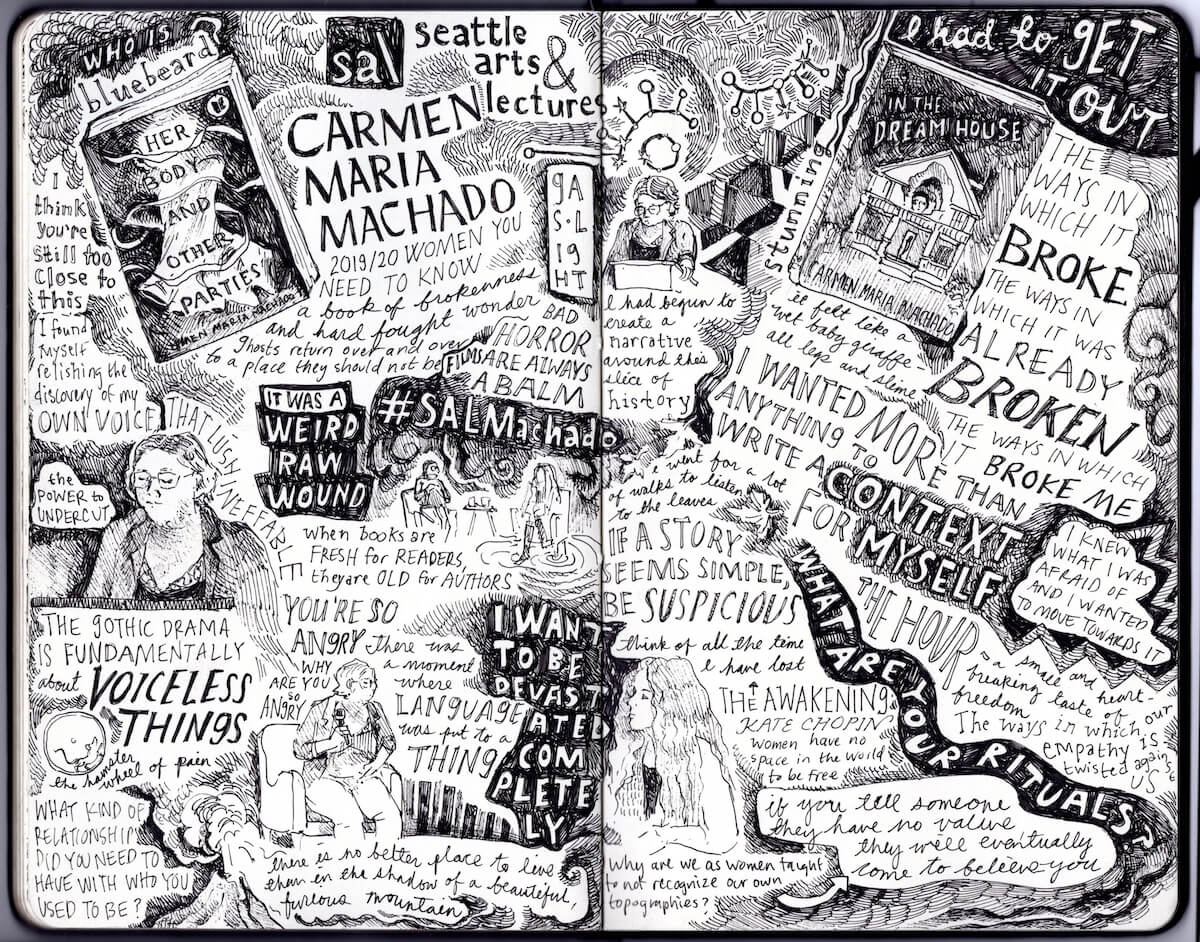

I am not at home to you: Dream House as book review

It is easy to compare a person to a house. Locked doors, crumbling foundations, and moist things lurking in the basement offer themselves up almost too eagerly as vessels for unfaced trauma, neglect, and shame. But this metaphor builds something neat and contained, a structure in which dots connect to expected dots, a coherent image at which we can nod in safe, unchallenged recognition.

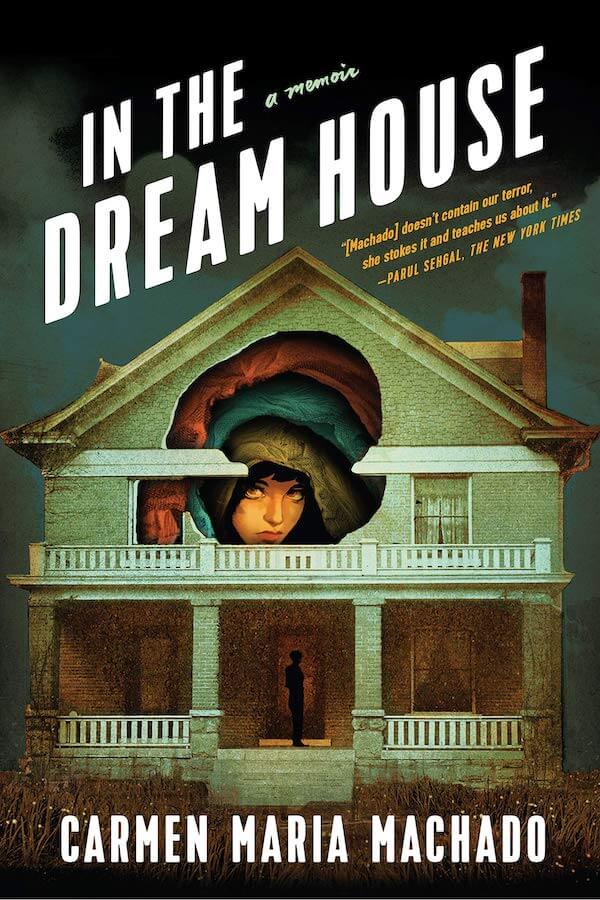

In her memoir In the Dream House, Maria Carmen Machado rips this trite simplicity to shreds, leveling the metaphor of self-as-house into a blurry growl. In her opening epigraph, Machado writes, “If you need this book, it is for you.”

I wish I didn't need this book.

But I do, so it is for me.

It is my book because Machado and I both know: on the far side of abuse, there is no greater necessity than telling your story and being believed.

On its most basic level, Machado’s Dream House is about an abusive lesbian relationship — an abuse that the larger culture does not how to acknowledge and therefore cannot allow to exist. But Machado's narrative surges across much wider ground, structuring itself as a series of staccato vignettes, each drawn from a different genre: Dream House as Idiom, Dream House as Naming the Animals, Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure. The end result is an intricately crafted explosion of a memoir that braids research and intimacy to stake its own existence. The heft of Machado’s book lays claim to abuse in a sharp-toothed demand for recognition.

Machado is nothing if not transparent: one of the book’s opening vignettes is titled Dream House as Not a Metaphor — ”I daresay you have heard of the Dream House? It is, as you know, a real place. It stands upright” — but even as she holds your hand and points to your destination, it’s a shock when you start moving. You are ill-prepared for the force of her velocity as her cadence pulls you into the frantic dissociation of a mind that has been trained to panic in the face of someone’s loving rage. Her words bring you into the home of yourself in lost flashes: A room. A room. A room. But there is nothing to link this assemblage, nothing to turn these disconnected places into something that belongs to a whole.

Part of this discomfort rests in the bones of Machado's voice, where the hammering weight of second person — you, you, you, you — forces the reader to experience the ceaseless erosion of self that occurs within abuse. “You were young,” she writes to both herself and you. “You didn’t know your mind could be a boon and a prison both; that someone could take its power and turn it against you.”

It is easy to disbelieve women; it is what our culture has trained us to do.

It is easier still to disbelieve women within the context of lesbian relationships, where there are no cleanly patterned gender roles to provide the false clarity of terms like perpetrator and victim. In a culture that does not even know how to acknowledge that lesbians can have sex — “they seem like sinners in theory, but with no penis how do they, you know, do it?” — how can we possibly believe that lesbians can abuse one another?

In the Dream House sinks itself into the jugular of this question, imbuing personal experience with the weight of research to explore a silence born from negative space. Machado writes of her relationship as an involuntary microcosm for lesbians as a whole:

Dream House as Double Cross

This, maybe, was the worst part: the whole world was out to kill you both. Your bodies have always been abject. You were dropped from the boat of the world, climbed onto a piece of driftwood together, and after a perfunctory period of pleasure and safety, she tried to drown you. And so you aren’t just mad, or heartbroken: you grieve from the betrayal.

You grieve from the betrayal.

Machado's Dream House is peppered with phrases like this, sentences that I found hard to read because the clamp of their concise jaws so perfectly captured my own experience of being devoured by a house. There is an extraordinary precision to Machado’s words, a linguistic control that captures the hinging nature of abuse — where something is okay until it is not, until a line is quietly crossed in a way that can’t be undone. “Abusers,” Machado reminds us, “do not need to be, and rarely are, cackling maniacs. They just need to want something and not care how they get it.”

Love and abuse stand in parallel, and Machado writes the agony of their blur; you buy a crumpling old house with your partner, but instead of changing the house's structure, the house changes you. “What does it mean for something to be haunted, exactly?” she asks. “You know the formula instinctually: a place is steeped in tragedy…. You were the sudden inadvertent occupant of a place where bad things had happened. And then it occurs to you one day, standing in the living room, that you are this house’s ghost.”

The shift takes so little; a house that is haunted becomes the house in which you are hunted; a love of being hallowed rasps against your chest until you are hollowed.

Oh how softly it slips, how gently.

Machado's memoir is deeply researched, and copious footnotes and academic sources contain the insinuated echoes of the times she has been dismissed as hysterical, emotional, and irrational (“This is what I keep returning to: how people decide who is or is not an unreliable narrator. And after that decision has been made, what do we do with people who attempt to construct their own vision of justice?”).

In the Dream House is Machado’s response to not being believed, and in one of the later vignettes — Dream House as Myth — she writes about the friends and community who know the woman in question and could not possibly see her as an abuser:

When you try to talk about the Dream House afterward, some people listen. Others politely nod while slowly closing the door behind their eyes… You will never feel as desperate and fucked up and horrible as you do when you hear those things. Once, a woman drunkenly touches your elbow at a party and says, “I believe you,” in your ear, and you cry so hard you have to leave.

For me — and for many, many others — In the Dream House is that woman drunkenly touching my elbow.

It means everything to be believed.

Toward the end of the book, Machado is at residency and struggles to find a point at which to bring the story to a close. She wrestles with the artificiality of this neatness; Dream Houses do not ever end, we simply fix them in time by pinning them to language. But the larger story of In the Dream House is about how shaping our own stories allows the space for others to shape theirs. Fittingly, Machado ends with the words of someone else’s story: “There is a Panamanian folktale that ends with: ‘My tale goes only to here; it ends, and the wind carries it off.’ It’s the only true kind of ending.”

And in ending this, I will do the same:

After a series of indiscretions a man stumbled homeward, thinking, now that I am going down from my misbehavior I am to be forgiven, because how I acted was not the true self, which I am now returning to. And I am not to be blamed for the past, because I’m to be seen as one redeemed in the present…

But when he got to the threshold of his house his house said, go away, I am not at home.

Not at home? A house is always at home; where else can it be? said the man.

I am not at home to you, said his house.

And so the man stumbled away into another series of indiscretions…

- (The Unforgiven, Russell Edson)

Tessa Hulls is an artist/writer/adventurer who is currently trying to hide in her studio for the next few years in order to finish a nonfiction graphic novel about the life of her Chinese grandmother, Sun Yi. Visit her website.

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound