If all Seattle read The Best We Could Do...

According to their website, the Seattle Public Library's Seattle Reads program is intended to "build connections between people through the shared foundation of reading the same book." When it was created by Nancy Pearl and leadership from the Washington Center for the Book, the Seattle Reads program was originally named "If All of Seattle Read the Same Book."

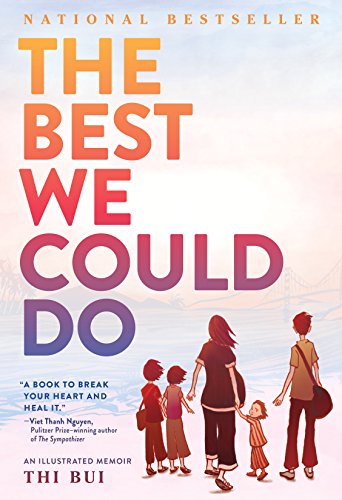

That original name is, obviously, better than "Seattle Reads." It clearly describes the intent of the program and lays out its aspirational tone. I especially wish that this year's Seattle Reads selection, The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui, still fell under the "If All of Seattle Read the Same Book" title. Because, simply, if all of Seattle read this book, Seattle would be a better place.

This month, Bui will come to Seattle for a series of readings and presentations and talks and appearances around town. On Saturday the 13th, Bui will be in attendance for a staged reading from the book, created by local theater stars Susan Lieu and Kathy Hsieh, with the help of Book-It Repertory Theatre. Even if you haven't read the book yet — and it is available at literally every library branch in large numbers, for free — you should attend one of these events.

Best is the second graphic novel selection of any iteration of the Seattle Reads program, and it's on par with the first — Marjane Satrapi's splendid memoir Persepolis — in terms of sheer storytelling power and craft. It shares themes with Satrapi's memoirs, too: a young woman whose family drama is swept up in the tidal wave of a geopolitical drama larger than any one person. But it differs wildly in terms of technique, and scope, and artistry. While Satrapi's book felt deceptively simple — like a fairy tale that grows darker in retrospect — Best grows more and more complex with each page, deepening in tone and twisting around itself.

The act of opening Best is enough to tell you you're reading something special. There's only one color in the book: an orange that soaks the pages like watercolor. Sometimes it's the dark orange of an angry sea. Other times it's an ambient glow, like the sky at sunset. It looks red at times, like blood. Sometimes the color disappears from the book entirely, leaving Bui's black and white illustrations to stand on their own.

Even without the expressive flourishes of color, those illustrations would be enough to anchor a reader firmly in Bui's story. She has a knack for facial expressions, and the intimate, telling glances between members of families — not an easy quality to capture in ink and paper. The majority of Bui's art is steeped in realism, but that makes the moments where she veers into symbolism feel even more potent.

Early in the book, Bui portrays herself with a giant hole cut out of her torso in the shape of Vietnam. In the sky in front of her, Vietnam looms in a dark orange. In captions studded with ellipses, Bui writes:

I began to record our family history...thinking that if I bridged the gap between the past and the present...I could fill the void between my parents and me. And that if I could see Viêt Nam as a real place, and not a symbol of something lost...I would see my parents as real people...and learn to love them better.

Best is that family history. Like most family histories, it spins forward, then backward, then forward in time again. (It's a little bit confusing at first; that's okay. If you lean in to the narrative, you'll eventually understand.) The story deepens as Bui adds more perspectives.

Best is a refugee story, a story of war and suffering and hope. Bui narrates as her family flees Vietnam and makes their way to America. Her parents aren't heroes — her father is a downright cruel parent, subjecting his kids to fear and confusion. But Bui's compassion for him allows her to find a path toward, if not acceptance, then at least understanding.

This is why all of Seattle should read this book. Best is a story about the sacrifices that people make as they become Americans, as they set their families down the path to a better life. That goal — the American Dream, it used to be called — is never fully attainable, but that's what makes it so important. That's why we can't turn our back to it, as badly as some may want us to.

Bui's investigation also demonstrates a meaningful path forward for children trying to come to terms with the successes and failures of their parents. Forgiveness isn't necessary, or even always desired, but perhaps with some understanding we can work to improve on the legacy left by the generation before. That's a lesson that every child should learn, and it's a lesson that we could all stand to recall as Americans right now, too.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound