Internet bites dog

On Friday, some people on the internet did what people on the internet do best: they stripped something of all context and then mercilessly made fun of it. This particular internet mob was a flurry of shitposters mocking the holy hell out of a children's book.

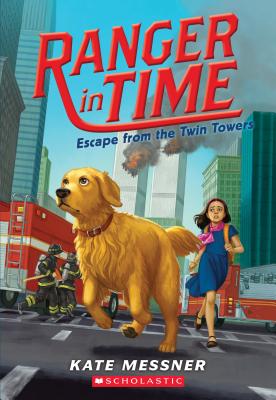

The object of Twitter's mockery was the latest book in a series for young readers: Ranger in Time: Escape from the Twin Towers. The cover of Kate Messner's book features a cartoon golden retriever with a determined look on its face running away from the smoking World Trade Center on the morning of September 11th, 2001.

Scholastic's promotional copy for the series reads, "Meet Ranger — a time-traveling golden retriever with search-and-rescue training...and a nose for danger!" Twin Towers is the eleventh book in the popular Ranger in Time series, in which the dog visits famous historical disasters to save a child or two.

But the idea of a 9/11-themed book about a time-traveling dog for elementary school audiences aroused the scorn of Twitter users, who spent the day kicking the book around:

...you couldn't have worse taste even if you cut your tongue out

— 🌑"Just Monika" = a valid Homestuck kid name🌑 (@MrVanillaMilk) February 28, 2020

I like that this dog is capable of time travel but not warning people about 9/11

— big time dumb ass (@boring_as_heck) February 28, 2020

What's that Lassie? Islamic terrorists are highjacking United flight 93 and is heading straight for the world trade center? ... That can't be right, Billy must just be stuck in the well again.

— Brickman409 (@mooseman409) February 28, 2020

Messner eventually caught wind of the viral mockery and published a tweet-thread explaining the idea behind the Ranger series. "I’ve written more than 30 books for kids, and [Ranger in Time has] been the most popular, by far," Messner tweeted. "The combination of a heroic dog, coupled with interesting history and lots of action, has a way of engaging even kids who don’t always love reading." In the thread, Messner explained the origin of *Twin Towers*:there are a lot of uhhhhh ones in this series it seems pic.twitter.com/5ZqX2sqGc4

— nathan guye shelton (@wiseposter) February 28, 2020

I spend a lot of time visiting schools to talk with kids about books and writing. At one of the first schools I visited after this series launched, a second grader raised her hand and said, “Could you please write a Ranger in Time book about 9/11?” I smiled & told her I’d put it on the list of ideas in my writer’s notebook. But in my head, I was thinking, “Uh…no. I can’t write a kids’ book about that. It’s too recent, too raw, and too sad.” But then more kids asked. Every time I visited a school. And I realized something. Those kids were born years after 9/11 and don’t have the memories we do as adults. To them, it’s an awful thing that happened in history, like Pearl Harbor is to many of us. They want to know more about it, but adults don’t like to talk about it. So kids are left wondering. So that’s why there’s a Ranger in Time book about 9/11 now.

Messner's candid explanation seemed to take the wind out of the trolls, and they moved on to tackle the next outrage of the day. Both the weird decision to make a laughingstock out of a book for children and the grace of Messner's reply stuck in my head, though, and over the weekend I bought a copy of Twin Towers at Eagle Harbor Book Company. I wanted to actually read the book that so many Twitter users had judged by its cover.

The Ranger in Time series is basically a canine-centric Quantum Leap reboot. It's the story of an aspiring rescue dog named Ranger who, even though he failed out of rescue training, desperately wants to be a good boy and save humans from disasters. (The reason for Ranger's failure was a squirrel with a "big, swishy" tail who tempted him from a rescue scenario. "Ranger knew that Luke wasn't really missing or in trouble on the day of the test," the reader learns early in Twin Towers. "If a real person had needed help, Ranger would have helped. But Luke was just pretending, so Ranger chased the squirrel instead.")

Ranger is in possession of a time machine that occasionally and with no warning sends him back to some point in history. The machine doesn't allow him to return to his own time until his rescue mission has been accomplished. It's a pretty straightforward superhero dichotomy: in his real life, Ranger is a rescue school dropout, but he gets to shine when he puts his modern rescue skills to the test in historical contexts.

This is a great gimmick for readers from 2nd to 4th grade: at that age, kids are old enough to understand that sometimes bad things happen, but they're young enough that they need to be comforted and reassured that someone will save them if things get too scary. Kids, in fact, are obsessed with watching things fall apart. The Ranger in Time books allow kids to be disaster tourists, watching normal systems break down within the safe space of science fiction, accompanied by a lovable, highly competent dog.

It would be easy for a lazy or incompetent writer to make Twin Towers feel exploitative or cheap. But Messner knows what she's doing: the book is exquisitely researched. The kids who need Ranger's help in the book are stranded in their mother's offices high up in the North Tower, and they need to reunite with their mother, who happened to go down to visit the Port Authority offices on the 63rd floor moments before the first plane hit.

Messner identifies the Tower's real tenants, and she doesn't allow for any "miracles" in her writing — nobody manages to jump to safety from the building's roof or using any other action movie tropes, for instance. If you set aside the time-traveling golden retriever who powers the plot, the rest of the story is as realistic as children's fiction possibly can be.

Nearly three thousand people died on 9/11, and Messner doesn't pretend that those casualties didn't happen. "Ranger had only trained to find people who were alive. But here, he caught a different, sad scent. People who hadn't survived." A younger, incautious reader might gloss over those words, thanks to Messner's nimble word choice, but older elementary-school kids will understand the implication.

Ranger experiences a trauma typical of other 9/11 rescue dogs: "Ranger's head felt heavy, and his tail drooped. How could he do his job when it felt like there was no one to save?" In the days after 9/11, rescue dogs became despondent after finding dead body after dead body, and emergency workers had to pretend to be caught in the wreckage and allow the rescue dogs to "find" them alive in order to keep their spirits up. Ranger doesn't fall for the trick — all that time-travel has turned him into a savvy pup — but he appreciate the effort to raise his spirits, and he keeps at it.

In the end, Twin Towers teaches children the inspiration that Fred Rogers shared when he briefly returned from his retirement immediately after 9/11: when things go wrong, and when everything seems hopeless, look for the people who are helping.

Why is it that the compulsion to sneer is so strong in humans? Why does it feel so good to join a mob of people on the internet who are gleefully kicking someone else's hard work around? It's easier, for sure. But it's much more rewarding to find the art and engage with it and learn its context.

In the end, the whole uproar over Twin Towers comes down to this: a group of adults saw a cover and decided to knock the book and its author around for sport. But they were actually mocking the newest generation of humans, who only want to understand the most unknowable parts of our history — the moments that those of us who lived through them will never forget. It's easy to jeer at youth and inexperience. But in the end, time makes a mockery of us all.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound