Laid bear

Let’s lay it out as simply as possible: Marian Engel’s Bear is a novel about a woman who has an erotic relationship with a bear. As you can imagine, this is the sort of premise that probably makes book cover artists lick their lips with anticipation.

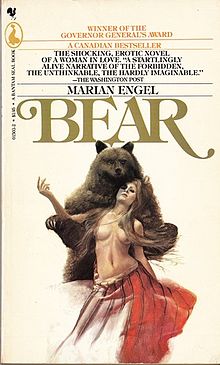

To the left of this paragraph, you’ll see the 1976 book cover for the paperback release of Bear. It is, as promotional materials for a newer edition of the book claim, “Heavy Metal-inspired," which is to say that it is lurid and shocking and fun, and also aimed directly at the adolescent male gaze. A menacing bear lurks behind a woman, his beady eyes and triangular claws glinting in the shadows of its fur. The bear’s fur and the woman’s long hair meld together into a chestnut-colored pool. The woman’s hair, improbably, covers the nipples of her naked breasts, even though most laws of anatomy indicate that the nipple of her right breast should almost definitely be revealed. Her hand is raised in a come-hither motion, and her eyes seem to be at once yearning for the reader and warning the reader away.

Last year, a screenshot of a Tumblr post about the cover for Bear appeared on the image-sharing site Imgur, and it went viral, with almost a million views. On Reddit and Facebook, people snickered at the cover, at its proud claims that Bear was a Canadian bestseller, and that it’s the winner of a Governor’s General Award, which, a poster assures us, is “the Pulitzer Prize of Canadian literature.” They call Bear a “Harlequin romance” — not at all true — and mock the book as though it’s a trashy romance novel for horny old maids.

Reddit user Kookiejar reviewed Bear soon after the Imgur post went viral. Perhaps “reviewed” is too strong a word; Kookiejar mostly offered a synopsis of the book leavened with intended-to-be-humorous commentary — “Is there enough bleach in the world to cleanse my brain from reading this?” — to assure the audience that s/he was maintaining an ironic distance from the text, and not enjoying it too much. There’s about one whole paragraph of actual reviewing in Kookiejar’s Reddit post, and here it is:

I think the author wanted this to be a feminist piece about how men are pretty much just like animals because you could have replaced the bear with a man at any point and not changed the jist of the book. In fact, the MOST uncomfortable (for the reader) sex scene happens between Lou and a human man. Unfortunately, the author failed to get this point across in any meaningful way and it ended up just being about a lady getting her crotch munched by a bear.

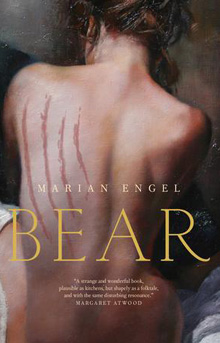

The book cover’s popularity inspired Penguin Random House to publish a new edition of Bear at the end of 2015. The new cover, credited to MaraLightFineArt.com, is to the left of this paragraph. We can see a woman’s naked back, with four ragged claw marks stretched across the right shoulder. She’s sitting, nude, on white sheets, and the rest of the room is obscured in a rich, dark, furry darkness. The image practically smells musky, like a bear, but there is no bear to be seen.

The new cover of Bear is a more austere image, one which plays into the more suggestive erotic covers of the modern age. Instead of thrusting hips or heaving bosoms, the flagship for the mass market erotic novel revival, the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy, all feature inanimate objects — a necktie, a mask, a pair of handcuffs — photographed lovingly. It’s less porny, less male gaze-y, and more suggestive. Rather than brag of awards or use Canada as a punchline, the only other writing on the cover of Bear aside from the title and author is a wondrous blurb from Margaret Atwood, calling Bear as “plausible as kitchens, but shapely as a folktale.”

It’s easy to admire the 1976 cover for its brashness. The 2015 cover’s failure to include a bear feels like a cop-out, a sop to more “realistic” modern tastes. But there’s surely something to be said for letting the browser’s imagination do the storytelling; the human-on-bear sex happening in the private thoughts of a customer in a bookstore is undoubtedly more graphic than anything you could stick on the front of a paperback. As we’ll see, in this way it’s a better counterpart to the text.

Last month, conservative blogger Matt Drudge spread a rumor that in the film The Revenant, Leonardo DiCaprio’s character Hugh Glass is raped by a bear. This isn’t true; I’ve seen The Revenant, and while Glass is mauled by a bear in a harrowing scene early in the film that seems to go on forever, there is absolutely no bear-on-man sexual assault.

Apparently, the rumor started when reviewer Roger Friedman wrote that “the bear flips Glass over on his belly and molests him – dry humps him actually – as he nearly devours him.” There is a moment in the bear attack sequence when Glass is crawling away from the bear on his belly, and the bear reaches out and grabs him and pulls him backwards toward it. It could, in the eyes of someone who is primed to see it that way, appear to be the beginning of a sexual assault. The scene isn’t an implied rape; it’s not really sexual at all.

The thing is, the internet seemed absolutely ready to believe the DiCaprio bear-rape story. On the morning that the Drudge link happened, Twitter began widely speculating about the scene. Collectively, the internet told itself: “That couldn’t be true.” But then the internet came back around and whispered to itself, “…could it?” Nobody had ever talked about The Revenant as much as they did in those 24 hours.

But why? Why are we fascinated with the sexuality of bears? Perhaps this is because bears, like gorillas and other large animals that can walk around on their hind legs, seem to us at moments like Humans in Furry Suits. But while most of us see gorillas behaving innocuously at zoos and in other docile settings — think Koko the gorilla telling a researcher in sign language how much she loves her pet kitten, which she named All-Ball—we are entirely petrified of bears.

And for good reason! Bears are terrifying. They roar and the parts of them that aren’t thick with fur are pointy and sharp. They’re heavy and they’re wild. And depending on the variety of bear doing the attacking, experts tell us in case of bear attack to either play dead or to run away. Even if we choose the correct survival plan for the correct type of bear (do we play dead when a black bear attacks, or do we play dead for a grizzly? Is running away from a grizzly bear fatal?) we might die anyway.

So we know that a bear’s anger is almost certain to be lethal. But what about its passion? There’s no better window to a human’s soul as that moment when they lose control, either through arousal or when they become entirely, irrationally angry. If a friend destroys objects or puts his fist through drywall when he loses his temper, that can be a scary moment of truth for people who thought they knew him. If a person behaves with intelligence and restraint even when they’re quivering with rage, our respect for them is likely to grow.

But we’re fascinated by that loss of control. We’re drawn to it. There’s a reason the English language is full of expressions like “I want to fuck you senseless” or “silly” or “stupid” or “like an animal.” The suggestion is that you have sex to get outside yourself, to tap into something rawer, more primal. In other words, to visit the place where bears live all day, every day. The symbolism of bear sexuality couldn’t be more obvious if you think about it: it’s a smelly, hairy, enormous stand-in for the loss of self.

And so finally we turn aside the cover of Marian Engel’s Bear and look inside. It’s the story of Lou, a librarian who takes an assignment on a remote Ontario island. She’s supposed to be investigating a collection for its historical worth, but she becomes enthralled with a semi-domesticated bear that lives on the property. (It’s telling that Lou never even seriously thinks to name the bear.) Her first sighting of the animal reduces her to a raw animal brain, aware only of the present moment and not one second before or after:

Bear. There. Staring.

She stared back.

Everyone has once in his life to decide whether he is a Platonist or not, she thought. I am a woman sitting on a stoop eating bread and bacon. That is a bear. Not a toy bear, not a Pooh bear, not an airlines Koala bear. A real bear.

It’s not “Me Tarzan, you Jane,” but it’s pretty close. You can practically imagine the bear standing there facing her, sniffing the air and making the same assessments in the ursine folds of its brain: “woman. Bread. Bacon.”

But soon, the bear proves itself to not be a threat — Lou was warned of the bear in advance and assured of its gentle nature — and the two take stock of each other.

The bear stood in the open, on all fours, and stared at her, moving its head up, down, and sideways to get a full view of her. Its nose was more pointed than she had expected — years of corruption by teddy bears, she supposed — and its eyes were genuinely piggish and ugly. She crossed the yard and pumped it a pail of water.

It’s not very long, a handful of pages, before Lou is inviting the bear into the house, his “claws clacking on the kitchen linoleum.” Lou notes that indoors, “he looked very large indeed. At the top of the stairs, he drew himself up to his full height, in that posture that leads the bear to be compared to the man.” She identifies him as “a cross between a king and a woodchuck.”

The sexy stuff doesn’t happen until later. Bear is a story of seduction, and so there’s a deferment of pleasure. For a book that barely crosses 100 pages, there’s very little of the language turned over to description of the sexual contact. (I’ll not quote any of those passages here, because it seems unfair to the book to rob it of the thing that draws readers to it.) Lou gets to know the bear, takes it in, and then she starts to touch it and to observe it up close. And then things start to happen.

I keep coming back to that Reddit review by Kookiejar, the claim that “you could have replaced the bear with a man at any point and not changed the jist of the book.” This seems to me to be a fundamental misreading of Bear. Sure, Lou has to humanize the bear somewhat; for one thing, it’s what we do to animals. We search their actions for something recognizable and we celebrate when they behave like humans.

But the bear is not interchangeable with a human. This is not the furry version of The Bridges of Madison County, nor is it Fifty Shades of Grizzly. Lou is aware that she is committing bestiality, that she’s having sex with an animal. She suffers very little guilt for it, but she doesn’t try to convince herself otherwise, either, that she’s doing something noble, or unselfish. But this isn’t just a story of sexual liberation, or a tale of finding your savage side. There’s a real transgression, and that’s part of what makes Bear so successful as a story.

I also have to take issue with Kookiejar’s claims that the book is “a feminist piece about how men are pretty much just like animals.” Bear, in fact, is barely interested in men, except for the one who has a retractable bone in his penis. The human man who Lou does have sex with in the book doesn’t register as a character, except for some unpleasant personality traits that advance the plot a little bit. No, this is a story of a woman, by a woman. But maybe some men have a hard time thinking of women as people; maybe some men think of women as something alien to their own experience, as distant as bears are to people. Maybe that’s part of the point.

Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, Margaret Atwood is exactly right. Bear works best as a weird fable. But it’s not the kind of fable where the bear is a good-hearted prince in disguise. And it’s not the kind of story where a brave woman is punished for trying to reach outside her experience. Even now, just shy of 40 years later, Bear feels like a new kind of fable, the sort of story that people will try to parse meaning from hundreds of years from now. This is, in every sense of the word, potent stuff.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound