Made for walking

One day, I walked out of the home I shared with a man and his six cats and into the desert. When I walked back into the city, I lived alone.

This is not exactly true. This is exactly true. I remember what it felt like to leave a crowded apartment before the sun came up and before the heat was overwhelming. I remember what it was like to crest the mountains and see the Las Vegas Strip rise out of the darkness. I don't remember leaving the apartment where I lived alone, and I don't remember returning to the place I lived with someone else.

As well as six cats, my boyfriend had seven countertop grills. One day a week, he hired someone to come in and clean. Seven grills meant that he could cook every day without ever washing a grill himself.

I use this story to help people understand that my boyfriend was odd, and not charmingly so, without saying anything that will be bitter if they press it against their palate.

The phrase "walking distance" describes a point that's close enough to reach by foot — not "by foot without walking oneself to death," but "by foot within convenience." Something that's walking distance can be reached regardless of the conditions of civilization. Can be reached without the permission afforded by gas tanks, managers, and other allowances and obligations.

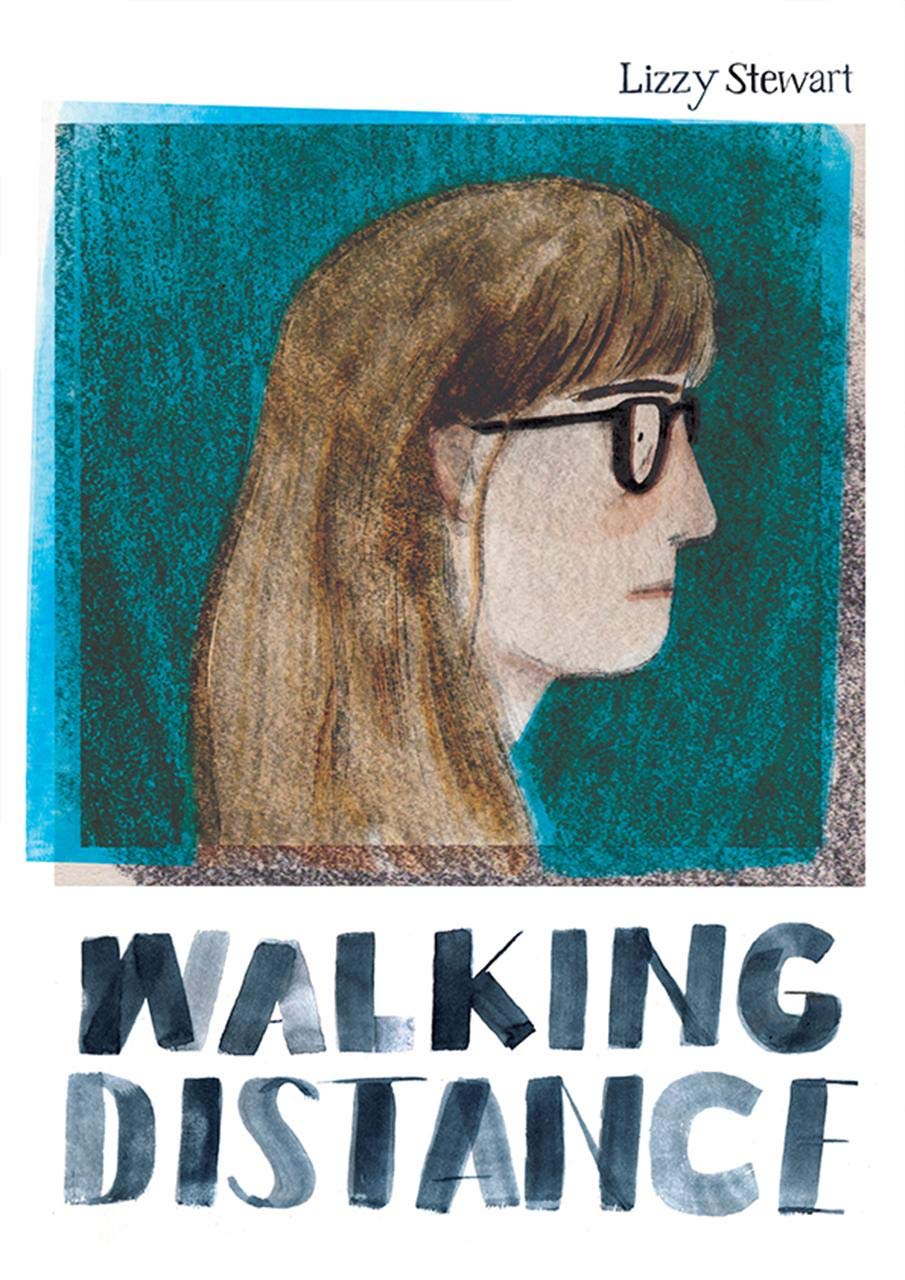

In that sense, "walking distance" may not refer to geography at all, but to a way of thinking. Wherever one is willing to walk is "walking distance" away. But is that right? It makes walking sound like drudgery, like a task — like washing one's own dishes. Drudgery is not what Lizzy Stewart is about in Walking Distance, but the strangeness and freedom of moving oneself through space. Not wherever one is willing to walk, but wherever one chooses to.

The (film-fictional) women in Stewart's book, including her (not-so-film-fictional) self choose to walk, and although their steps are very ordinary — down city streets, past shop windows — watching them makes Stewart’s heart skip. They are women in possession of their own lives, in possession of their own steps, in their own cities, alone.

Stewart's book is neither exactly a graphic novel, nor exactly an illustrated narrative, but walks the line (apologies) between the two. Everything about it is peripatetic. That's why it's so damn good; reading it is very much the print experience of a long walk: half meander, half destination.

In the course of Walking Distance, Stewart considers womanhood; adulthood; the difference between herself and her mother at the same age. Fashion, and large coats; social media and focus and distraction. Current events as a murder of crows, compared to the murderous black dog of depression. One topic folds into the next, and text folds into swashes of black, grey, and blue-grey ink, just the way a walker's attention shifts from what she sees to her eternal internal monologue.

One particularly astonishing page reads like her notes for the book:

Something about housing and how it is awful.

Something about politics and how it is awful.

Something about the patriarchy and how it is truly, fucking awful.

How twitter makes me sad.

…

The NHS is being torn apart.

Racism exists everywhere and it's long past-due time to stop pretending otherwise.

...

What will happen to the libraries?

One page shows Stewart as a giant, striding above the London suburbs. Another is populated by illustrated tiles, perhaps an inch to a side: a building’s side, a bush, a car, off-center and partial, as glimpsed by someone moving quickly. Another — water? Clouds? Or simply the way darkness makes the world anonymous when we walk through it at dusk?

The conventions of narrative would provide a clearer itinerary, but every walker knows that maps are liars.

“I suppose I am trying to work out the shape of my life,” writes Stewart. “Which is probably an unnecessary task, but one that I am committed to nonetheless.”

What is is about walking that loosens the mind, that loosens the spirit from the obligation of certainty? Frees us from the measured allowance between “start” and “stop”?

A fascination with walking isn’t unique to women; one of the co-founders of this publication is a man, a known walker, and a lyrical writer about walking. But the pages of Stewart’s book are populated with the faces of women, and it’s women whose walking captivates her.

Women may not endure greater constraints than men, all told (here, again, I worry about what a bitter flavor does to belief). But perhaps the kind of freedom walking demands works particularly well against the kinds of constraints women face: fear, shame, aggression. A woman walking is a target, but she is also a declaration.

At one point, walking was my escape; at another, it became my declaration. Every time I came home, I arrived a little farther away.

I could fill this page, for all its infinite scrolling, with stories about walking. Some are angry stories, about being dogged for miles by men who believe a woman walking alone is a woman seeking company. About walking for miles when it was the only thing I was allowed to do alone.

But I’m reluctant to subordinate walking to the anger of men. Walking is a way to “form a detailed map” of the world, to know it intimately through boredom, through fear, through delight, through exhaustion. A woman walking learns which ways are “quickest, slowest, best lit, most beautiful.” That has nothing to do with monstrous men. It has everything to do with the kind of quiet defiance that refuses to be shaped by tyranny.

What Lizzy Stewart says, in the purposeful meander of her images and text, is that walking is how we can lose and un-lose ourselves — by our own volition. And by own volition, if anything, is how we will move forward now.

Dawn McCarra Bass is associate editor at the

Seattle Review of Books and co-director of the Pocket

Libraries program, which channels high-quality donated books to

people with limited access to reading. By day, she’s the founder

of Mightier, a small

consulting firm where women solve problems creatively, collectively.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound