Moving pictures

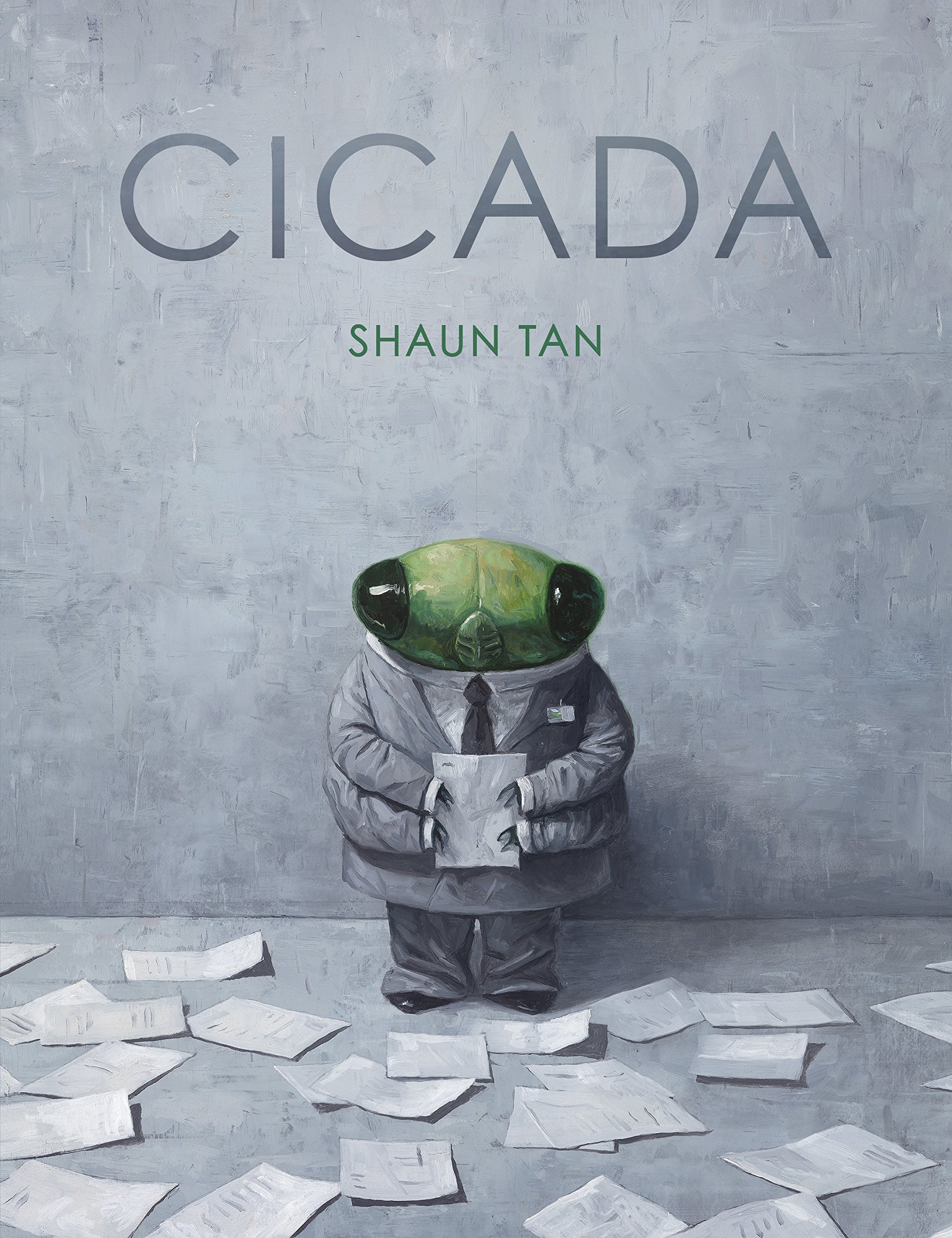

Cicada has been at the same job for almost 20 years. It’s a shadowy grey cube farm where he enters data into the night, long after his human colleagues have gone home. He’s bullied and passed over for promotion (“Human resources say cicada not human . Need no resources.”). He lives in a crawlspace between offices — just cicada, a teapot, and tomorrow’s suitcoat hanging from a pipe.

Life for cicada is pretty grim. Or, as he puts it at the end of every haiku-like bit of self-narration, “Tok Tok Tok!”

I have a feeling Shaun Tan has been asked too many times to explain who he writes for. Tan makes picture books — a genre presumptively for children — that flirt with darkness and disquiet. (One benighted Publisher’s Weekly review says he “saturate[s] readers with ennui.”) He’s drawn picture books on colonization, on loneliness, on despair. And yet they’re clearly … picture books. Short, simple in structure, rich in illustration, light on narration. It raises all sorts of confounding questions about genre.

And who is less likely than an exhausted parent, looking to soothe or distract a fretful child, to be interested in confounding questions about genre? Hence an endless series of reviews, of The Rabbits, The Red Tree, The Lost Thing that warn Tan’s work is “for mature children or young adults” (if professional) or that ring with righteous parental indignation (if on Amazon.com).

Tan says, with remarkable restraint, that he prefers to focus on the commonalities between older and younger readers. “We are all interested in playing. We like to … bring our imagination to the task of questioning everyday experience”:

What matters are ideas, feelings and the pictures and words that build them. How can they be playful and subvert our usual expectations? What are the ways that something can be represented to most effectively invite us to think and ask questions about the world we live in?

What ideas and feelings do the pictures and words build in Tan’s Cicada, with its uncanny child’s-eye-view of the modern office? Marginalization. Otherness. Isolation. Despair. Stories about work are deeply resonant; we invest so much in work we need so much from it, we are so easily damaged by it. We surrender power — the more so, if we are small and green and insectile (metaphorically) in a world of large, white bipeds — in exchange for survival, and sometimes little more.

Cicada is loyal and hardworking, but the system is structured against him: he was never going to get ahead.

No work. No home. No money.

Cicada go to top of tall building.

Time to say goodbye.

But Shaun Tan’s books are about questions, not answers. They are fables, not morality plays, offering us “unusual things that encourage us to ask questions about what we already know.” Playfully, Cicada displaces us within the most common setting possible, and we scramble to make it familiar again. The grown-up mind reaches for Kafka, for Melville’s Bartleby, for issues of income inequity, bias, immigration.

The grown-up mind glosses over a casually dropped clue at the opening of the book, distracted by the story it thinks it knows.

A compact green insect with bulging eyes mounts an Escher-like maze of stairs. He stands on the corner of the tall building where he’s worked for 17 years, hunched slightly forward — leaning toward the drop. A bright orange tear opens across his back. The shell of his suit falls away.

He flies, into a sky filled with other bright, airborne cicadas.

Cicada all fly back to forest,

Sometimes think about human.

Can’t stop laughing.

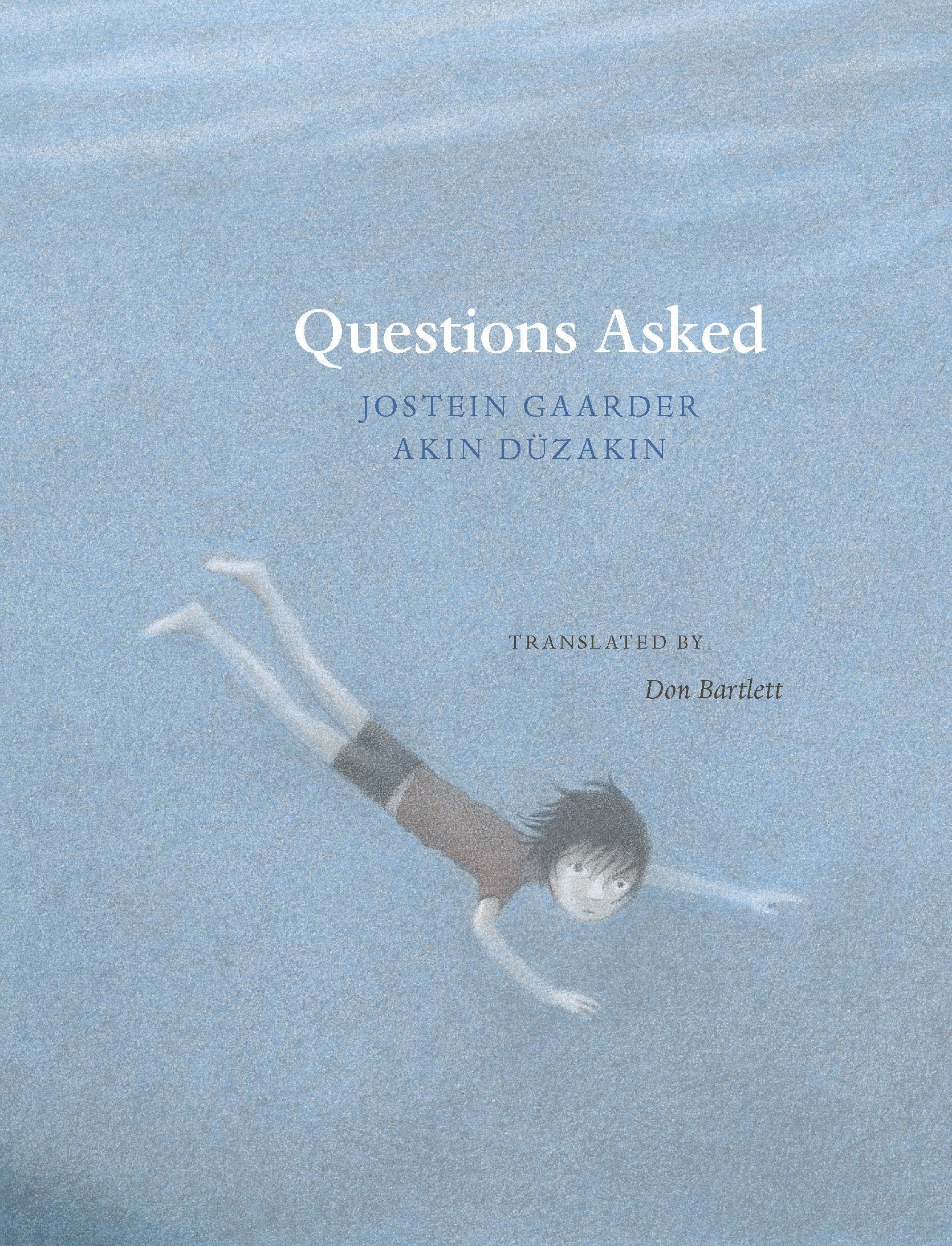

Questions Asked, written by Jostein Gaarder and illustrated by Akin Düzakin, is a different sort of inquiry. Gaarder is an intellectual and a philosopher; his best-known work is Sophie’s World: A History of Philosophy, which may be the book most often given to “bright” young women by well-meaning relatives.

Skim through the book, glancing at images and capturing scraps of text, and here’s what you’ll see:

A small boy runs alone through a forest, deer fleeing beside and around him.

Is it possible to be afraid without knowing what you’re afraid of?

A torn photograph of two children playing.

Can I be sure that all my memories really happened?

An open suitcase, underwater. The current carries its contents away.

Are experiences more real when I’m awake then when I’m dreaming?

Out of sequence, this looks like nonsense (and feels like it, as opposed to looking like nonsense while whispering intriguingly to the lizard brain). Read sequentially, a pattern emerges: The book is a set of philosophical questions, paired with the story, told only in images, of a young boy bereft of his twin brother.

The questions are about fear, grief, loss, love — all the big heady stuff of life. And it’s interesting to see those abstractions set against concrete moments in which a human might consider them. But their mystery seems reduced by the exercise, not enriched. It’s as if out of a myriad of meanings, the author has selected just one thought, and then pinned the question to it like a stunned butterfly to a mat. Which, in a way, he has.

When it works, the pairing of picture and query lifts Düzakin’s illustrations out of the merely pretty. A charming drawing of the boy tumbling from a ladder into soft leaves, books and papers flying from his hands, gains edge when it’s placed next to “What do I fear losing most?” When they work, the pairings push through the boundaries of both the words and the pictures.

But for the most part, they don’t. This book knows much too well what it means to be a picture book — to answer, to soothe, to stick to the well-trod narrative path.

Shaun Tan says The Lost Thing, which asks questions about alienation and loneliness and also has an adorably awkward monster, “began as a small unimportant doodle in a sketchbook … serious attempts of ‘I’m going to write a good story’ all too often end up as miserable failures.” Good stories are explorations, not roadmaps. They’re the brush of an idea’s wing against the reader’s mind. What happens after that is between the reader and the page.

Dawn McCarra Bass is associate editor at the Seattle Review of Books and co-director of the Pocket Libraries program, which channels high-quality donated books to people with limited access to reading. By day, she’s the founder of Mightier, a small consulting firm where women solve problems creatively, collectively.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound