Selling mansions in heaven

As a lifelong atheist and comics fan — maybe not necessarily in that order — I was especially primed as a young man to fall in a kind of kitschy love with Jack Chick’s comics. In the late 1990s, I embraced Chick’s comics on the same level of so-bad-it’s-good appreciation that others would bring to a cheesy horror movie, say, or an embarrassingly mediocre record purchased from the discount bin at a thrift shop. From the smarmy name — “Jack Chick” sounds more like a pornographer than a preacher — to the ubiquity of his books, I fell hard for the man’s work. * I read pretty much all the Chick tracts I could get my hands on, and eventually someone bought me a complete set as a birthday gift; as a result, I devoured hundreds of pages of Chick’s comics in a week.

And now Jack Chick is dead. All his comics are available for free on Chick Publications' website, and in the days since his death I’ve been flipping through his digital tracts, many of which I haven’t read in a couple of decades. I cannot discern at this point whether my reaction to Chick’s work now differs so wildly from the days of my youth because social mores have changed, or because my personal tastes have changed, or both. But these books are, quite simply, not fun anymore.

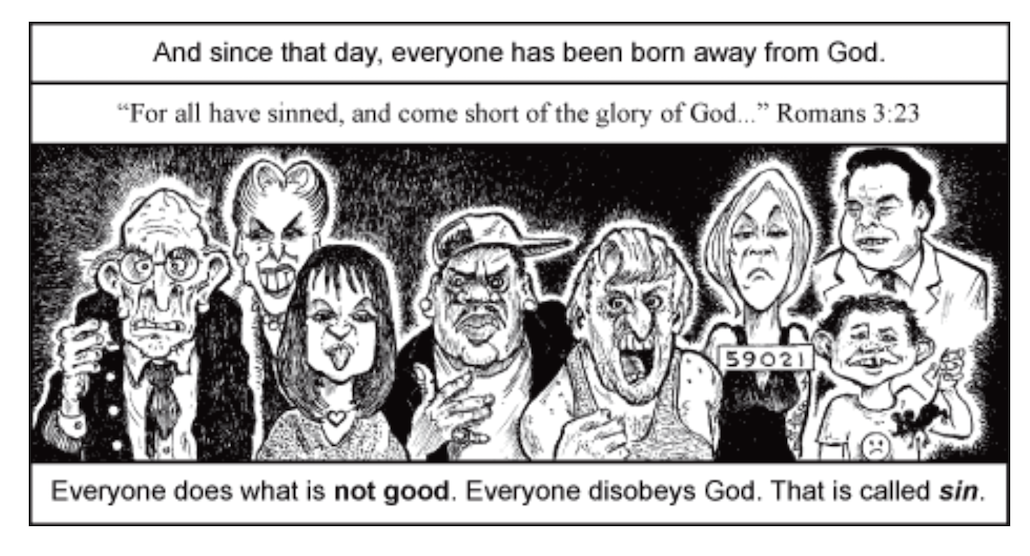

When Jack Chick looked out at the world, he saw nothing but ugliness and despair. Take a look at this panel, which is typical of Chick’s view of humanity:

These people — who Chick defines as “everyone” — are hideous. Deformed. They’re racist caricatures and monsters, leering at the reader in defiance and rage. Not one of them could be characterized as attractive, or kind, or pleasant. “Everyone does what is not good,” Chick warns in a caption. Perhaps because every Chick tract is couched in the language of a sales pitch, the tortured phrasing dances around the statement that “Everyone is bad,” but that’s what he is saying. That’s what he believes.

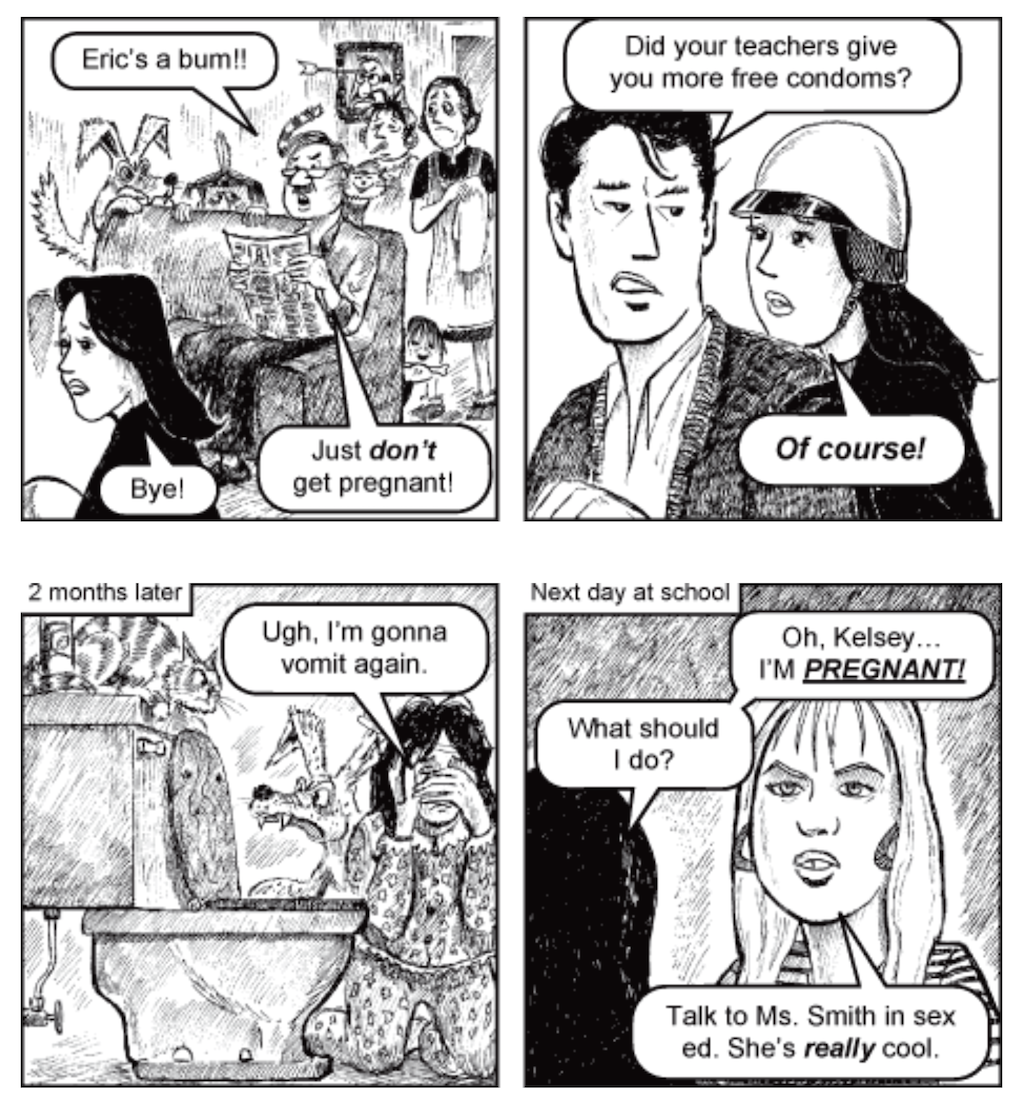

And here, in an anti-abortion pamphlet, is what he believes liberal American culture to be:

The uncaring parents, the dismissive friends, the “cool” authority figures, the arrow in the father’s forehead in the background. Society is rootless here, filled with rutting subhumans who can’t control themselves. Chick is documenting what he believes to be the destruction of western civilization. Is there any doubt that if Chick had his faculties in his dying days, he would most likely have been a believer in Donald Trump’s calls to Make America Great Again? Even if he could not morally support Trump the man, Chick surely believed with all his heart in that message.

In another tract, a liberal college professor asks if any of his students disagree with the idea of evolution. One student, the brave and handsome Christian, raises his hand and proclaims, “I do, sir!” The professor loses his mind: “You can GET OUT of MY class!! After you’ve apologized to everyone for your rudeness and ignorance, we MIGHT let you back in!”

Note that the professor turns over from “my” to “we” in the span of two sentences. He’s an unreasonable jerk who immediately loses a hold on his temper if he’s questioned, but he’s also a collectivist. The religious student uses “I” language, while the professor, after a territorial mention of “my,” speaks in “we” and “our.” If she weren’t an aggressive atheist, Ayn Rand would no doubt thrill to the exploits of Chick’s protagonist in this strip as he does battle with the mediocre masses. The lines of battle are clearly delineated in Chick’s comics, and he doesn’t bear a whit of sympathy for the other side.

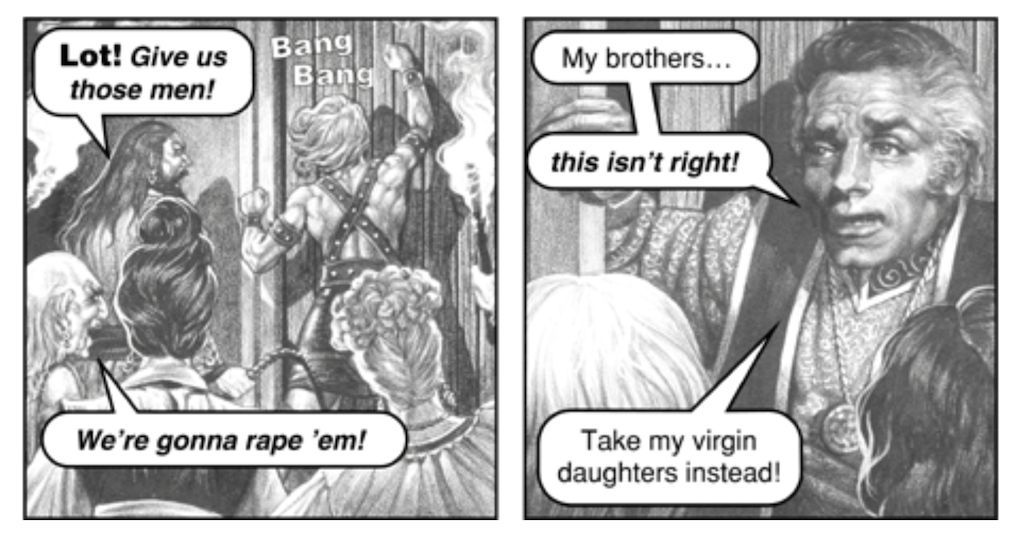

Let’s be clear: like many evangelicals, Jack Chick’s Christianity isn’t interested in what’s good or right. He spells this out again and again when characters plead with heavenly figures that they’ve tried to be good people. Again and again, those people are cast into hell, to be tortured for all eternity. Chick doesn’t care about goodness or kindness. He is concerned with saving mortal souls, and those souls can only be saved by accepting Jesus Christ as their personal savior. Bad people are rewarded by last-minute turns to God, and good people suffer for their ignorance of God. Here is the story of Lot, which Chick is eager to portray as a story of heroic selflessness:

Chick loves to portray the hungry fires of hell and the sneering enthusiasms of demons. He spends much less time illustrating the rewards of heaven. He is overly fixated on the book of John chapter 14, verse 2, which in the King James text promises that “In my Father's house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.” And so most of what we see in Chick’s heaven are large and “beautiful” mansions where “those who are saved will live in… FOREVER!”

The way heaven is portrayed in Chick comics is not especially desirable: for Chick, heaven is a cul-de-sac of McMansions, which he portrays in a cloudy distance, viewed from below and obscured by light from above. His characters discuss those mansions in the unthinking, covetous spirit of a pre-Great Recession real estate agent: everyone wants a mansion because everyone wants a mansion. What do people do all day? They live in mansions. Do they like it? Of course; they’re living in mansions.

And Chick portrays God in the same aloof, undetailed fashion that he illustrates heaven: his God wears flowing robes, but he has no features: no facial hair, no hair, no ears, no face. It’s a blank wig dummy’s head planted on top of a muscular body. His God can’t smile or frown or laugh. His face is a blank canvas, which Chick fills with dogma. God doesn’t matter to the stories so much as the words that God has to say — the unquestioning and brutal judgment he casts on humanity at every opportunity.

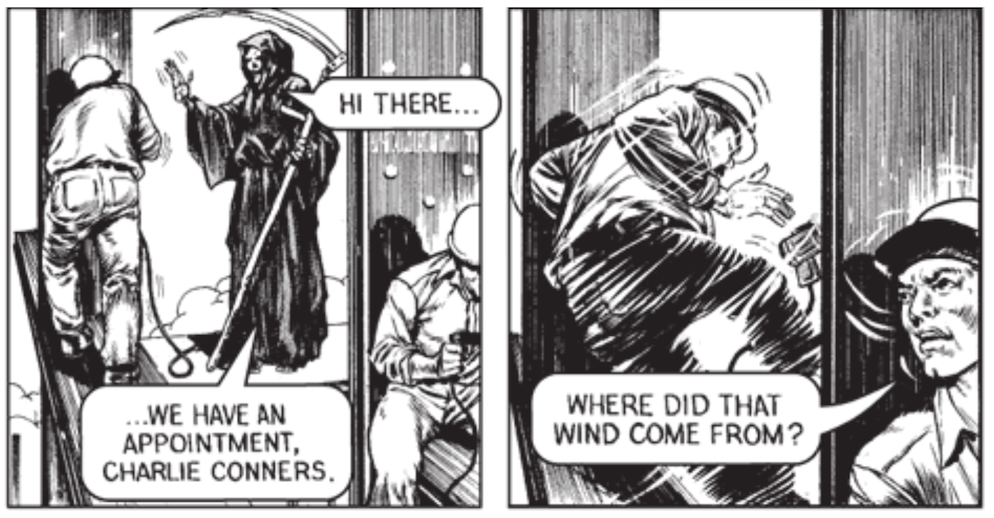

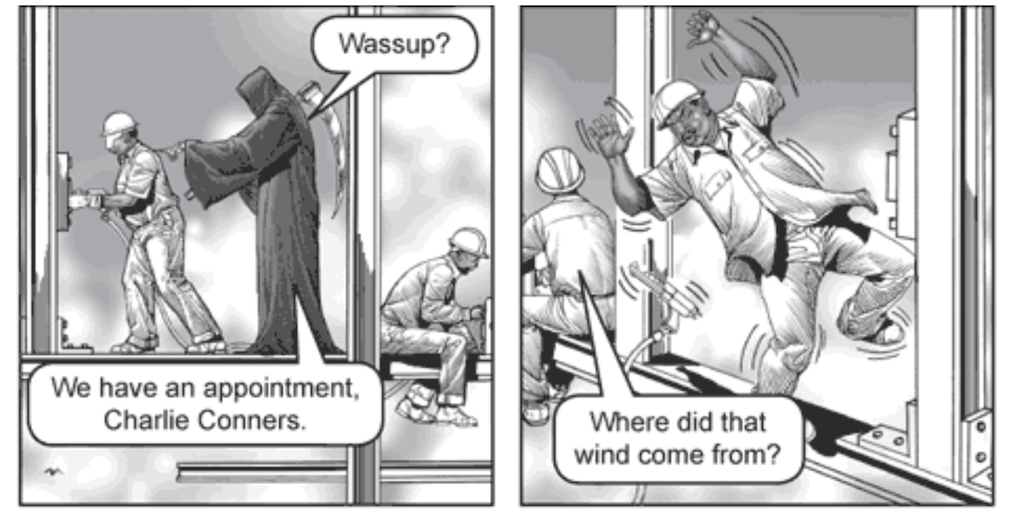

For such a prolific cartoonist, Chick was not especially good at communication. He tailored several of his strips specifically for black and for white audiences. Here’s a passage from a strip titled “Hello There”:

And here’s the same passage from a strip titled “Wassup”

Chick wasn’t an especially good cartoonist, either. He was too reliant on words to tell a story, often jumping around in time with little concern for narrative cohesion and relying on enormous hunks of exposition to get the story told. He’d rarely include backgrounds in his comics, and the body language of his characters never feels any more subtle than the acting in a silent movie. This is the work of an artist who doesn’t trust the medium in which he works, and the stiffness of his comics — the bad dialogue, the hammy “acting” of the characters — is likely what gives them their kitschy appeal.

And so here we are again, talking about kitsch and the ironic appeal of Chick’s comics for people who are decidedly not in his target demographic. It was easy for me, as a young straight white male, to enjoy Chick’s comics. Except for the atheist bit, Chick was pretty much on my team: the people who suffer in his books are usually women and people of color. The white men are almost always saved by the end — even Bad Bob, the eponymous biker who murders and rapes and sells “acid, smack, dust, coke, speed, and black beauties” to people who find him to be “crude, rude and socially unacceptable” before finding his way to Jesus on the penultimate page. (“At this point, Bob becomes a child of God. he is born again and made spiritually alive,” Chick writes in a caption. “He will not go into the lake of fire, but will go to heaven," probably to live in a mansion filled with mansions.) We watch Bob abuse women and destroy property before he's saved, but we don’t see any of Bob’s good works after he’s been saved. Presumably, the deeds don’t matter; only the saving does.

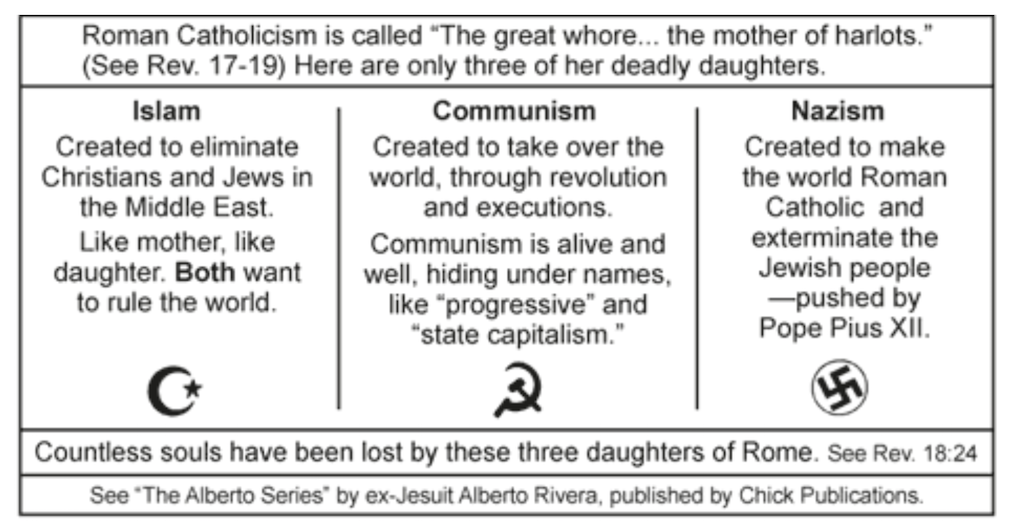

I can’t really enjoy Chick tracts anymore, but I am still fascinated by them — particularly in those moments that offer a glimpse of the man behind the comics. The fact that Chick blames Catholics for virtually every group he hates, from Nazism to Islam, feels like a personal vendetta that extends beyond mere doctrine. This is the work of a man who hates Catholicism on a deeply personal level:

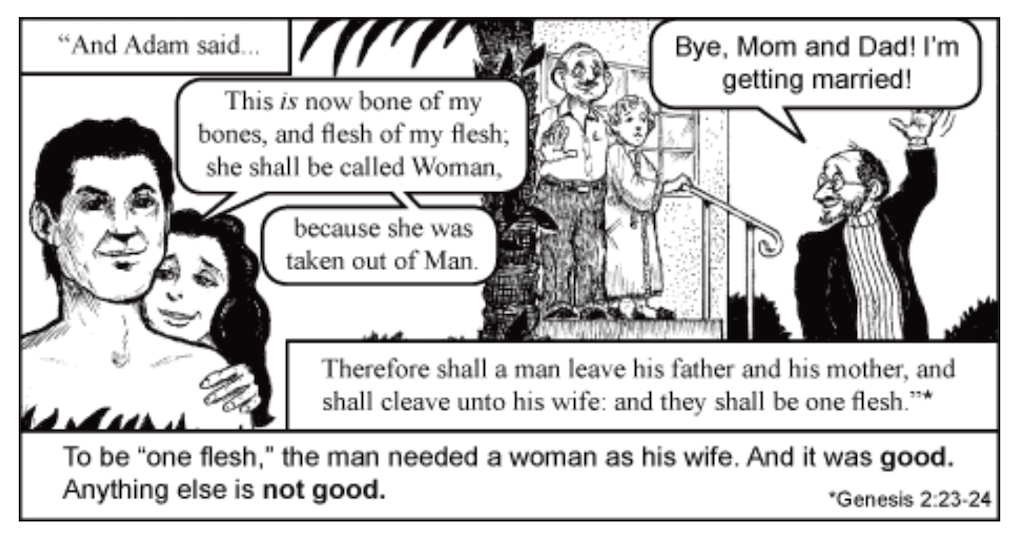

And while Chick seems to work hard to scrub his comics of anything but what he perceives to be Jesus’s message, he occasionally lets slip with a few moments that reveal his interior life. Take this passage, from a pamphlet about the sanctity of marriage:

It’s supposed to illustrate a passage from Genesis about “a man leav[ing] his mother and father, and…cleav[ing] unto his wife,” but there’s something deeply wrong in this interpretation of the passage. Look at that balding, paunchy man on the right side of the panel. “Bye, Mom and Dad! I’m getting married!” he says, even though there’s no bride in the panel. His father waves goodbye, his hollow eyes betrayed by a strange smirk. And while his father is dressed in a button-down shirt and dress pants, his mother stands silently, looking wan, in a bathrobe and slippers, grasping onto a railing for support. Aren’t they going to their middle-aged son’s wedding? Did he just tell them he’s getting married as he was leaving the house? Has he really lived at home for 45 to 50 years? Why wouldn’t Chick just draw a young man in his 20s, for ease of visual communication?

This panel, I think, might be the closest Chick has ever come to a self-portrait. Even if Chick doesn’t look like the schlub in this panel, it’s an illustration of a deeply lonely person — someone who has no idea how relationships actually work. Rather than the happy ending where the couple kisses at the altar, Chick draws the man alone, setting out far too late in life to claim his happiness. It’s a moment that has apparently been a long time coming, and it feels artificial and emotionally false. It’s a drawing of a man with a profoundly shuttered psyche — a man who never once managed to open his heart or his mind to anyone else. It’s a moment of happiness, illustrated by someone who has never been happy.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound