Short Run for the long haul

Conventions are strange. We find them appealing because they’re momentary — they exist for a day, or a weekend, and then they’re gone. But we also become attached to specific conventions; we get used to the rhythms and organizational themes, and we get upset when we feel that a convention has “betrayed” its original voice. So we expect conventions to be transitory, but we also demand consistency from convention organizers. This is a thankless job.

Organizers Eroyn Franklin, Kelly Froh, and Janice Headley have done remarkable work maintaining the consistency of the Short Run Comix and Arts Festival. For an event that has moved three times in less than a decade— from the Vera Project to Washington Hall to Fisher Pavilion at Seattle Center — Short Run has kept its scrappy, let’s-put-on-a-show enthusiasm through every transition. This is not the kind of convention that will be swallowed up by, say, Wizard World. It’s fiercely independent, and that spirit has enabled its exhibitors to demonstrate an ownership that you don’t find in other conventions. Walking in to Short Run is like visiting a neighborhood, albeit one where Fantagraphics and Chin Music Press and Sparkplug Comics live on the same block. It’s kind of like Sesame Street, with Seattle cartoonist Greg Stump as Big Bird.

This year’s Short Run was undoubtedly bigger than ever. Was it better? I think so. The expanded space at Fisher Pavilion made walking around the exhibitor tables less of a claustrophobic experience and more of a stroll. You had to expect some loss of character in the move from Washington Hall to Seattle Center — the Hall has rambling hallways and multiple floors and a separate event space, whereas Short Run this year took up one mammoth floor. The programming seemed to have less emphasis this year, taking place off to the side of a roaring convention hall. But if your Short Run experience is less about attending readings and more about checking out the tables, you likely thought it was the best show yet. (And besides, Short Run organizers have done a good job of spreading the programming out throughout the month of November, with readings and exhibits and concerts happening all around town; keeping the focus strictly on the convention on the day of the convention is probably a wise move.)

Walking around the floor of Short Run is always overwhelming. If you try to pay attention to every single table at the show, you’ll be flat broke in a dozen minutes. You have to pick and choose, an experience which can always be a little stressful when you have young cartoonists struggling to make eye contact with you as you breeze by their tables. You have to carve your little world of attention out of the galaxy you’re given.

A good place to start at nearly any Seattle-area comics show is David Lasky’s table. Lasky always manages to put together a few new comics for every show. At this Short Run, he had a pair of experimental zines. Ideas for Short Comics: Challenges and Games is a print-only zine, with a different idea for a comic constraint on every page of the. One idea:

Set out to make the most uneventful comic possible. Have things happen, but make them insignificant. Force the reader to wait for something interesting to happen, but (like Tarkovsky in film) keep them intrigued enough to stay with you by giving them interesting settings and objects to look at, and/or quiet, seemingly deep characters. See how long you can keep it going. Don’t succumb to drama.

Another idea: “Adapt Moby Dick as a single-panel gag cartoon.”

Lasky is one of Seattle’s finest cartoonists, a tireless innovator who always examines the concept of what comics can do. Challenges and Games is a little peek inside his process. Young cartoonists will likely find a whole year’s worth of projects in the book, and by the end of the year, they’ll be better cartoonists for it.

The newest minicomic from Lasky this year highlights his more literary side: The Ultimate Horatio Alger Novel: As Chronicled by the Covers from Some of His Stories is exactly what it says it is: a “comic book” telling a classic Horatio Alger rags-to-riches story, using only tiny color reproductions of classic Alger book covers. The story begins on the first page with our main character, Tony the Tramp, and it broadly tells the story of his American ascension through Alger’s novel titles: Driven from Home, Sink or Swim, and so on. Lasky points out that some of Alger’s titles are quite suggestive when you consider that Alger was a closeted gay man: Slow and Steady, Strong and Sure. It’s a tiny little book that will take you at most a few minutes to read, but Horatio Alger works on so many levels: it’s comics, it’s literary criticism, it’s biography, it’s a solid literary joke. I’d expect no less from the cartoonist who launched his career with a pair of adaptations of Ulysses.

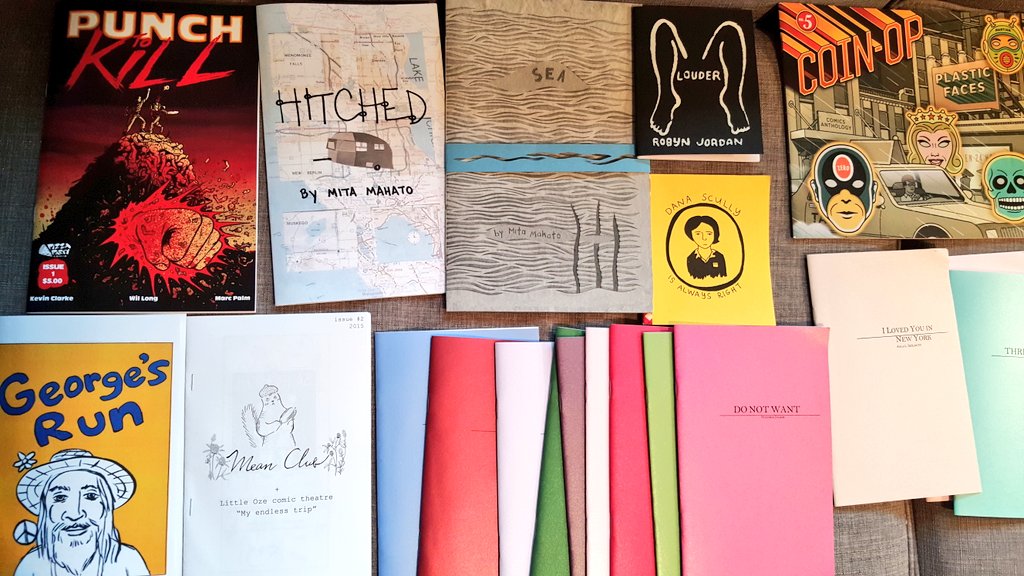

Some of the best minicomics at Short Run are the experiments, the somewhat messy one-joke wonders that function like the comedic version of a drive-by-shooting. By the time you realize what the cartoonist is up to, they’re already gone. Sarah Mirk’s minicomic Dana Scully Is Always Right is maybe the best joke of the show, in part because it springs from a deep and abiding X-Files fandom. The book consists of a crude drawing of Gillian Anderson’s character from the X-Files on each page, saying dialogue taken directly from the show.

And, in fact, Mirk is telling the truth: Scully is always right. “Visions of deceased loved ones are a common psychological phenomena,” Scully says on one page. On another, she peers around suspiciously, saying “It’s not until you get back to nature that you realize everything’s out to get you.” The book is a charming fan letter to one of the strongest female leads of 1990s television, and a good, cheerful joke about the formulaic nature of the X-Files.

Henry Chamberlain’s minicomic George’s Run is a fascinating take on the biographical comic. A text introduction explains that George’s Run is just the first chapter of what Chamberlain hopes will be a longer work focusing on George Clayton Johnson, a writer for the Twilight Zone and Star Trek, as well as the creator of Ocean’s Eleven and the co-creator of Logan’s Run. Chamberlain identifies Johnson as “a member of the mid-20th century group of Southern California science fiction writers that included Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, Theodore Sturgeon, Bill Nolan, and Charles Beaumont.” The story begins plainly enough, with Chamberlain in Las Vegas, preparing to interview Johnson. But he intersperses those scenes with a number of wordless and captioned panels that tell Johnson’s story in a refreshingly non-literal way: a young boy runs down the Yellow Brick Road to a gigantic radio, and then he sits and listens to the radio’s strange, swirling patterns — presumably, early sci-fi serials — that swirl in the air around him. This representational take on biography is challenging and occasionally frustrating, but it’s never boring.

The beauty of a show like Short Run is it values individual experience, not corporate cash. What that means is that every aisle of the show featured work that self-described as feminist, or which challenged gender norms, or which dismantled societal understanding of what “normal” means.

Seattle cartoonist Robyn Jordan’s Louder: Shouting My Queer, Sort-of Abortion is exactly what it says it is. Inspired by the #shoutmyabortion movement on social media, Jordan tells the story of her recent ectopic pregnancy that was ended with a treatment of methotrexate. Jordan’s brother tries to clarify, “But it’s not really an abortion. Is it?” Jordan isn’t hearing it: “Well, yeah. I mean, if abortion were illegal, this wouldn’t be legal.” It’s a small story, but it’s a valuable one; part of what #shoutyourabortion has demonstrated is that if Christian decency keeps womens’ bodies shrouded in mystery, it’s easier to control those bodies through anti-abortion laws. When women like Jordan tell their stories, it makes it impossible for conservative anti-abortion forces to demonize them and their choices.

Another feminist book I picked up at the show, The Important Business Ladies’ Guide to Important Business for Ladies, examined themes like workplace harassment, gender pay inequality, and the history of women in the workplace. Cartoonists Jennie Yim, Emily Alden Foster, and Abigail Rae Young use a combination of comics, text, and multimedia art to tell the stories of women in the workplace. They interview their grandmothers about what it was like to take jobs for the first time. They talk about their own worst jobs (Young’s account of working in the fashion industry is maybe the most illuminating — and horrifying.) They photocopied a few pages of Sheryl Sandberg’s supposed feminist manifesto Lean In with handwritten “suggested edits” drawn on top. (One note accuses Sandberg of body-shaming her pregnant self for telling an anecdote using the words “waddling” and “whale” to describe herself.) It’s a substantial, funny, and philosophical look into the state of workplace feminism in the early 21st century.

One of the most satisfying aspects of an annual show is stopping by to see how the young talent is advancing. Margaret Ashford-Trotter has been producing minicomics in Seattle for a few yyears — Thunder in the Building, her earliest work, was promising, though with a little stiffness in both the art and the storytelling. Her newest minicomic, Hey Frankenstein, demonstrates that practice pays off. This is a short story about decisions: a young woman doesn’t want to visit a party. Two young men at the party get into a fight. Ashford-Trotter tells the story out of chronological order, not to build suspense but rather to build character. Just as her art has become a little looser—people don’t stand quite as stiffly as they did in her earlier work, and their faces are much more expressive—her storytelling confidence has increased. It’s a terrific combination, and a sign that she’s on the right path. Hopefully, we won’t have to wait until next year’s Short Run to see something new from her.

Mita Mahato’s paper-cut comics don’t quite look like anything you’ve ever seen in a comic book before. Her book Hitched is made from collage layered on top of maps, telling the story of a pair of stowaways. They ride around the country by hiding in the trailers of tourists (“Those old husbands and wives never left each other’s driver’s sides. We exited their trailers as soon as their car engines whirred off.”) It’s a beautiful comic that lays a road trip across maps of the United States; a map of New York City has a few paper-cut skyscrapers sprouting across it, for instance, and a stand of green-paper cacti pops up just outside of Las Vegas. It’s a beautifully told American myth, a gorgeous artifact and a compelling story.

Mahato’s newest book, Sea, is a wordless comic depicting a pair of whales swimming across a seascape, all rendered in grey-toned paper cuts. Every page has dozens of slithering waves fastidiously cut out with, presumably, an X-acto knife. Each of the tendrils of a jellyfish overlap and crisscross the waves as it swims across panels. A school of fish whirls around, following some mysterious path. It’s a beautiful book — easily the most beautiful thing I picked up at Short Run — and it captures the mystery and the darkness and the majesty of the sea in a new way. Like Hitched, it’s breathtakingly beautiful, but it’s beautiful in a completely different way. With just a handful of books, Mahato has become a name to watch in the Seattle comics community. Whatever she does next will undoubtedly be an event.

Short Run wouldn’t be Short Run without at least one discovery that seems to appear out of the ether, like a magical antique shop in an old ghost story. For me, that enchanted discovery was Coin-Op Comics, a brother-sister comics act from California. I picked up two issues of their anthology comic, Coin-Op, and I haven’t felt this giddy about a discovery in a long time; it’s the same kind of feeling I felt when I happened upon my first Chris Ware book in a bad comics shop in the Maine Mall — a sense of stumbling across a new, complete world. In part, I make that comparison because Peter and Maria Hoey’s artwork is reminiscent of Ware’s antiseptic ragtime draftsmanship. But while Ware is a tireless formalist, the Hoeys devise a new style for every single story, giving off the vibe of a traveling theater company doing a dozen one-act shows in a half an hour.

The very short stories in Coin-Op are set in different worlds and they vary in degrees of abstraction. One story is set in a deranged nightclub staffed and attended entirely by robots. Another features Orson Welles. In one story, wind ruins a parade as a pair of pigeons tell jokes to each other. The only recurring characters are a pair of cartoon dogs named Saltz and Pepz. In one story, they accidentally get stuck in money-making machines at the U.S. Mint, and in another they travel through time to meet Thelonious Monk. These are gorgeous comics that will haunt your dreams and leave you craving more. I’d never heard of Coin-Op before, and I’m almost worried that if I tried to locate them online, they’d prove to not exist. Their books are that otherworldly, that magical.

So Short Run, for me, was undoubtedly a success. I met with old friends, I met a few cartoonists for the first time, I gossiped, I introduced a publisher to a project. I learned about Sanpomichi, an artist who’s making a stop-motion animated film about a pair of mice in a Pioneer Square loft. I got to see the first iteration of Jaimee Garbacik’s Ghosts of Seattle Past project (which—full dislosure—I’m a contributor to). I bought a copy of Jim Woodring’s brand-new 3D comic. I picked up a few books I’ll be reviewing on this site in weeks ahead. I spent way too much money. I left with the feeling that it’s impossible for one person to understand the depth and the breadth of the comics scene in Seattle, and with the sense that the coming year would reveal some astonishing new work from local talent. The show only lasts for one day, but the community Short Run has created is out there in Seattle, making and reading and sharing new work all year long. We all live in this neighborhood now.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound