Show the backlist some love!

For the first month of the year, those interested in children’s literature speculate frantically about which books will win the American Library Association’s book awards. And when the winners are announced, sales go up. Before Kelly Barnhill’s The Girl Who Drank the Moon received the 2017 Newbery Medal, its sales were 17,484. After it won, the number shot up to 56,653 — a 324% shift. The same goes for the year-end lists produced by organizations and book lovers to promote the “best” children’s or young adult books published that year. Across the country, librarians and booksellers will study the “best of” lists and the lists of award winners and add multiple copies of them to their shelves. Displays of these books will spring up in libraries and bookstores everywhere. Book lovers will scour the lists and fill their library requests and their shopping baskets.

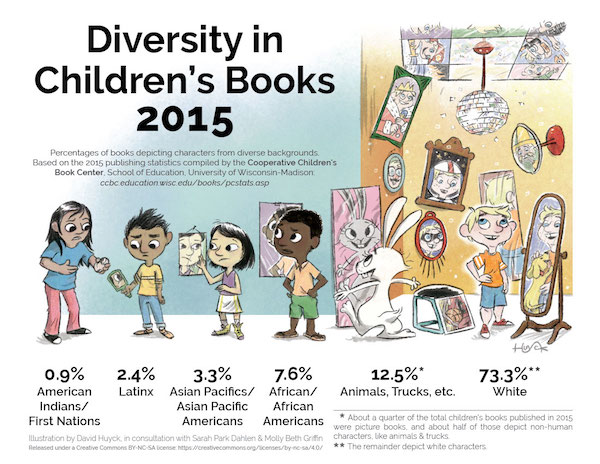

New and award-winning books, in other words, get a lot of love and attention. America’s status-driven, consumerist orientation means Americans strive to get the newest this or that, and while I’m thrilled that people buy new releases, I think it’s important to show some love to older books, too — especially books written by Indigenous writers and Writers of Color. I am, by the way, tribally enrolled at Nambé Owingeh, which is one of the Pueblo Nations in New Mexico. Accurate books about Indigenous people don’t fare well in bookstores, and they don’t circulate in libraries very much (which leads to them getting weeded — pulled from the shelves to make room for newer or more popular books). Those books are few, every year, in comparison to books about White characters and, well, animals and inanimate objects.

The Native girl in the image above isn’t smiling for two reasons. First, she’s got a tiny mirror. Second, the image in the mirror doesn’t look anything like her. When most people think of American Indians, the image that comes to mind is not someone dressed like the child shown in the graphic. What does come to mind are images that suggest we’re people of the past. Tragic or bloodthirsty, primitive or all-knowing — it doesn’t matter. The image is of someone in buckskin and feathers, standing by a tipi or totem pole, or riding a horse in pursuit of a buffalo. Books with characters that “look” Indian are bestsellers. Paul Goble’s books, for example, are everywhere and never go out of print. But many of his books, especially those about Iktomi, have been thoroughly criticized by Professor Elizabeth Cook-Lyn and librarian Doris Seale, both of whom are from the tribal nations those stories belong to. And his award-winning The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses is completely made up: it looks and feels like an Indigenous story, but it is a product of Goble’s imagination.

The kind of books that people ought to buy, if they have a genuine interest in Indigenous people, are books like Simon J. Ortiz’s picture book, The People Shall Continue. Published in 1977 by Children’s Book Press, the book begins with Indigenous peoples on our respective homelands, then moves through history — including accurate depictions of violent, oppressive actions of the US government — right up to the present day, where Ortiz writes about the need for all peoples to work together to fight greed and capitalism and the forces that harm humanity and the earth.

Ortiz’s words do important work. He uses the word “nation” rather than “tribe”; most people know about treaties, but the idea that we were, and are, sovereign nations isn’t addressed — even in current state history standards. Instead of “braves,” he says “men.” Instead of “squaw” or “papoose” (these are Algonquin words, used by speakers of that language, but it’s incorrect to use them for people of other nations) he uses “woman” and “baby.” And he doesn’t hedge on brutal episodes in history like US government boarding schools designed to “kill the Indian and save the man.” The goal was to destroy every aspect of Indigenous culture. Children were given new, English names; punished for speaking their own languages; and in many instances, physically and sexually abused by staff at the schools.

Most White writers think that honest depictions of incidents like these are not age-appropriate. But that worry is for White kids, not Native ones. Our kids know our history. And they feel betrayed when they don’t see it represented. But for years, The People Shall Continue, a book in which Indigenous children can see history as they know it, was out of print. We're lucky Lee and Low — a small publisher — brought it back into print in 2017, to mark its fortieth anniversary.

Expectations of what Native characters and stories should look like are one reason a book sells (or doesn’t sell) in bookstores or online. Ideally, books would have long-term support from their publishers, but that is not the case. When a book comes out, a house may promote it vigorously for six months — and then a new crop of books comes out, and marketing moves on. Within six months of its release, then, a book goes onto a publisher’s backlist. This means that those few books that are published each season that show characters from diverse backgrounds — look again at the percentages in the illustration above! — lose even more visibility and children who seek those books are dealt another blow.

Some of that is changing, as we move ever more deeply into a digitized world where “print on demand” means more and more books will never really go out of print. But even so, books must be made visible — which brings me back to awards and year-end book lists — and all the other lists that drive attention to the “newest and greatest.” Next time you look at one of these lists, figure out whether any of the books on it are by authors who are Native, or African American, or Asian American, or Latinx. Those are the four groups in the United States that are most commonly regarded as “minority” because of demographic and historical oppression. If you’re looking at an all-White list, pop down to the comments and say something! And if you create lists, make sure you’re not creating all-White lists. Give books by not-White writers a boost.

And if you’re reading these words and can’t name more than five Native writers, come on over to my site, American Indians in Children’s Literature. Take a look at my Gallery of Native Writers and Illustrators. Learn their names! Better yet — make a list of their names and take it with you to the library. If you can’t find their books, ask the librarian to order them. Take your list to the bookstore, too, and if their books aren’t on the shelves, ask the clerk to order one for you. If you’re in a book club, suggest their books. In short: be a change agent by asking for and talking about these authors and their books.

Anyone who follows social change knows that over time, publishers respond to shifts in societal demographics by publishing different books. Institutions shift, too. The Association of Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, voted at its midwinter meeting in February 2018, to revisit the names of some of its awards because the work done by the authors for whom those awards are named is not inclusive. The first one they’ll study? The Laura Ingalls Wilder Award.

Times are changing. Demographics are changing, too. Children’s books can help us all embrace change — if we look for those that accurately represent the many peoples in American society.

Tribally enrolled at Nambe Pueblo — a sovereign Native Nation — Debbie's writings on representation of Indigenous peoples are taught in English, Education, and Library Science courses in the United States and Canada. In February of 2018, the American Library Association selected her to give its prestigious 2019 Arbuthnot Lecture. Visit her at americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/.

Follow Debbie Reese on Twitter: @@debreese

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound