Spanish lessons

For the past two years, I’ve been working on my Spanish through self-study exercises and reading. Without the luxury of a tutor, I can barely manage a simple conversation, but I can read through a Spanish-language Kindle book.

The Kindle is ideal for language learners: Highlight a word and the dictionary entry shows up on the screen. Highlight a phrase and you get an idiomatic translation. Sure, it’s not perfect, but it’s good enough.

The trick is to read each paragraph over and over again until you can fully understand it without looking up anything. Then, go to the next paragraph.

Using this approach, it took me about four months to read Isabel Allende’s El amante japonés (The Japanese Lover), and two months to complete her latest novel, Largo pétalo de mar, which will be available in English as A Long Petal of the Sea in January 2020.

In these two novels, Allende intertwines the stories of families living through historical periods that have particular resonance to the present moment. For example, here’s a description of an internment camp for Japanese-Americans at the start of WWII, from El amante japonés1:

Topaz, almost a mile above sea level, was a horrendous city of identical and flat constructions, like an improvised military base surrounded by barbed wire with tall control towers and armed soldiers. It was an arid and helpless place, wind-whipped and crossed by dust swirls.

The other concentration camps for Japanese out West were similar, always located in desert areas to discourage any attempts at escape. No glimpse of a tree, nor a thicket, nothing green anywhere. Only rows of dark barracks extending towards the horizon as far as the eye could see.

Families stayed together, holding hands without letting go, so as not to get lost in the confusion.

Well, it’s almost resonant with current events. These days, we forcibly separate families, whether or not they’re holding hands.

In El amante japonés, we meet Irina Bazili, a young woman from Moldovia with a mysterious past, who lands a job working at an eccentric and pleasant San Francisco assisted-living facility. Among the residents is Alma Belasco, a wealthy older woman with a mysterious past, and her grandson Seth, who has a thing for Irina. Obviously, there is also a Japanese lover, Ichimei Fukuda, a survivor of the aforementioned internment camps. Irina and Seth coax the story out of Alma, episode by episode, even as their own relationship slowly blossoms.

Allende has a knack for sketching out people we meet only briefly, as well as for unfurling the full extent of a complex life history across generations. It’s the stuff of life itself. Everyone has a story to tell. Sometimes we get to hear it all, and sometimes we just have a few short moments. Allende’s generational storytelling talents are also on display in Largo pétalo de mar, which, like El amante japonés, contains chilling historical parallels. These not only resonate with the present, but also contain implicit warnings about the impending perils of fascism.

Largo pétalo de mar starts during the Spanish Civil War. Victor Dalmau is a medic, and his brother Guillem is a soldier, both on the side of the democratically elected Republicans fighting against the fascist, Franco-led Nationalists.

Their father, Marcel Lluis Dalmau, is a piano teacher with a passion for social justice. On his deathbed in 1938, Marcel Lluis correctly judges that the fascists will win the Spanish Civil War, and so he extracts a promise from Victor to get his promising piano protégé, Roser, and Victor’s mother, Carme, out of Spain.

Keeping his promise, Victor puts Carme and Roser into the capable hands of his trusty ambulance driver, Aitor Ibarra, who must convince Carme to leave Barcelona:

Until the final moment, Carme doubted the necessity to go, saying that there’s nothing bad that lasts 100 years, and perhaps they could wait and see how things went; she didn’t find herself capable of starting a new life somewhere else, but Aitor gave her vivid examples of what would happen when the fascists arrived.

First, flags everywhere and a solemn mass in the main square, attendance mandatory. The victors are received with cheers from a multitude of enemies of the Republic who had remained disguised in the city for three years, and with cheers from many others, driven by fear, trying to seem pleased while giving notice that they had never participated in the revolution. “We believe in God, we believe in Spain, we believe in Franco. We love God, we love Spain, we love Generalissimo Francisco Franco.”

Then the purge starts.

First they arrest the combatants, if they find them, in whatever condition they’re in. And then they arrest people denounced by others as collaborators, or those suspected of some activity considered anti-Spanish or anti-Catholic; this includes union members, left-wing parties, practitioners of other religions, agnostics, Freemasons, professors, teachers, scientists, philosophers, Esperanto scholars, foreigners, Jews, gypsies, and so on down the list.

In January 1939, Barcelona’s exiles arrive at the chaos and death of the French border, already closed to the masses of Spanish refugees. Anyone who survived crossing the treacherous mountains would likely end up in a French concentration camp, just months before France falls to the Nazis.

Victor and Rosa escape the carnage of wartime Europe through the humanitarian efforts of the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, who (in reality as well as in the novel) chartered a ship to take Spanish exiles to safety in his home country.

If you know your Chilean history — and you will after reading this book — you’ll know that danger lurks just a couple of regime changes away.

Before reading Allende, my most vivid picture of the Spanish Civil War came through Hemingway’s Robert Jordan, the American volunteer soldier in For Whom the Bell Tolls, and my awareness of Chilean politics was a hazy recollection of Pinochet’s crimes. Allende’s storytelling brings these historical episodes to life with characters you’ll never forget — especially if you’re slowly reading and re-reading each sentence in a language not your own.

The editors of The Seattle Review of Books have invited me to be a reviewer-at-large and write regularly on the book (or books) of my choice.

I take this responsibility seriously, which means that I can’t just rattle on as usual about talking dogs. No, I have to branch out.

In this space, I want to recommend works in the genre of literary fiction that not only represent or portray Seattle but also speak to this particular moment in our shared history. Here are a few more books that I consider Seattle-y — and only one of them takes place here.

The Mars Room, by Rachel Kushner (2018) A line that aptly summarizes the novel: “Unfortunately for that baby, it was a girl.”

The baby in question was born to a fifteen-year-old girl who goes into labor during the intake procedure for a women’s prison in California.

Romy Hall, the mother of a four-year-old, comforts the screaming girl. For her trouble, Romy is placed in administrative segregation on her first day serving two consecutive life sentences for the murder of her stalker. Romy had met the man at her workplace, a strip joint called the Mars Room.

This isn’t Orange Is the New Black. What sets it apart is the realistic detail and the relentless snuffing-out of hope. But Mars Room does have something in common with OITNB in how the narrative switches perspectives to secondary characters: Doc, a crooked cop in prison for his role in a contract killing; Sammy, a former narcotics addict who teaches Romy how things work inside; and Gordon Hauser, an all-but-dissertation academic teaching prisoners to read when not being played by them.

Hauser lives in a cabin in the woods near the prison. It’s his “Thoreau year,” he tells his friend, who replies: “Your Kaczynski year.” The novel includes brief excerpts from the Unabomber’s diary, angry and increasingly violent responses to the encroaching world, with the effect of extending the gloom of the prison to the great outdoors.

Still, The Mars Room is written with a light touch, and it never bogs down.

And as a book reviewer, I also have to applaud the book-review-within-a-book, for Pick-Up, a 1987 novel by Charles Willeford about a pair of alcoholics.

I told Hauser I read Pick-Up. He asked what I thought.

“That it was good and bad at the same time.”

“I know what you mean. The end is a surprise, right? But it makes you want to reread the book, to see if there were earlier clues.”

I told him I’d done that. And that it was good to read a book about San Francisco, that I was from there.

“Oh, me too,” he said.

He didn’t seem like it to me, and I said so.

“I mean, near there. I’m from just across the Bay, Contra Costa County.” He named the town, but I hadn’t heard of it.

“It’s an armpit behind an oil refinery. It’s not glamorous, like being from the city.”

I said I hated San Francisco, that there was evil coming out of the ground there, but that I liked Pick-Up because it reminded me of things about the city that I missed.

Which brings me to my next book, set mostly in Manhattan and the Hamptons.

Fleishman Is in Trouble, by Taffy Brodesser-Akner (2019) With its relentless parade of online dating escapades, this book combines the carnality of a Philip Roth novel with the cutting incisiveness of a Tom Wolfe satire in its portrayal of wealthy Manhattanites.

Toby Fleishman is a short, middle-aged, just-separated hepatologist whose soon-to-be-ex-wife Rachel leaves him with their two kids when it wasn’t his turn. Not only does this put a wrench in his surprisingly active dating life, he’s in the running for a big promotion at work, and now he has to get the kids into summer camp all by himself while finding out whatever happened to Rachel Fleishman.

The end was a surprise, and it made me want to reread the book to see if there were earlier clues.

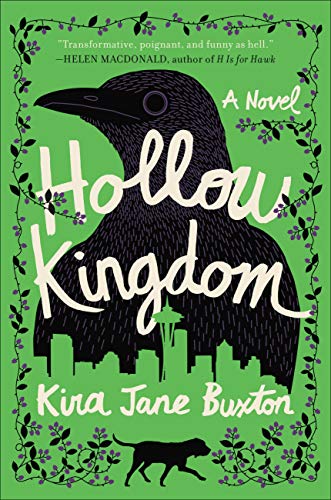

Hollow Kingdom, by Kira Jane Buxton (2019)

You want a Seattle story? Here’s a Seattle story. Humanity starts to fall to pieces — literally, as in people’s eyeballs falling out and limbs tearing off, leaving their twisting heads swiveling and lurching towards anything that resembles the glass of an iPhone screen.

A talking crow named S.T. teams up with a bloodhound named Dennis to figure out what’s going on, in an adventure that takes them all around a still-recognizable Seattle transformed by nature and taken over by all manner of dangerous varmints. My only beef with this book is that Dennis the bloodhound is just about the only non-talking animal in the entire novel. The main character is a talking crow, but it doesn’t stop with crows, not by a long shot. There are talking birds of all kinds, a talking polar bear, talking octopus, talking cow, talking cat, talking frog, you name it. The trees, they talk too. Elephants, turns out they’re into spoken-word poetry. I suppose that had Dennis been a talking dog, he would have been a scene-stealer. At least in the movie version, I’m sure Dennis will get plenty of screen time and a pretty sweet plush toy, so I’m good.

Earlier this month, the author gave a reading at Queen Anne Book Company. She read the first chapter about the talking crow, and then read the talking-cow chapter in a Scottish accent that would have sounded entirely authentic had I not been able to understand what she was saying.

Buxton also talked about her deep love of animals and her personal relationship with the crows in her neighborhood, which makes sense.

Hollow Kingdom was an enjoyable and funny read with a clear environmental message: If it comes to a zombie apocalypse, you’re dead meat, so maybe make some animal friends before that happens, okay?

Have a pleasant autumnal equinox, and see you around the solstice.

-

This is my translation, not the official one. When browsing another of Allende’s works in English, it seemed to me that parts of the translation tried too hard to mimic her long, flowing sentences. Spanish and other Romance languages have a certain grace in how they join together winding and wending dependent clauses that flow together without losing track of the referent. By contrast, English works best as stubby sausages: SUBJECT-VERB-OBJECT, full stop. Although an avid reader of translated works, I’m glad that I’m not a translator. Translation is relentless butchery. Full stop.↩

Ivan writes shelf talkers for Mercer Street Books. You can also find him at www.ivantohelpyou.com.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound