The aggressively passive voice

Seattle author Richard Chiem's fiction often centers on characters who may as well be ghosts. His protagonists feel little or nothing. They push forward out of sheer momentum, waiting for something to happen. And even if that something does happen, it often barely even registers with Chiem's characters.

When reading one of Chiem's stories, I often think of Spike Lee's signature dolly shot, in which a character moves, somehow passively, through the world. They stare straight ahead, often into the viewer's eyes, and they move through their surroundings without a feeling of weight or belonging or consequence. Like this:

Most writing teachers will warn you against passive characters — they'll tell you that every story is about someone who wants something. They'll say it's impossible to move a narrative forward when that narrative is about someone who is numb.

It's a good thing that Chiem didn't listen to those writing teachers — his fiction uses passiveness to great effect, employs it as a way to examine the world. By stripping desire and ego from his characters, he pares a story down to its most essential parts, and allows the reader to layer their own experiences over what they read.

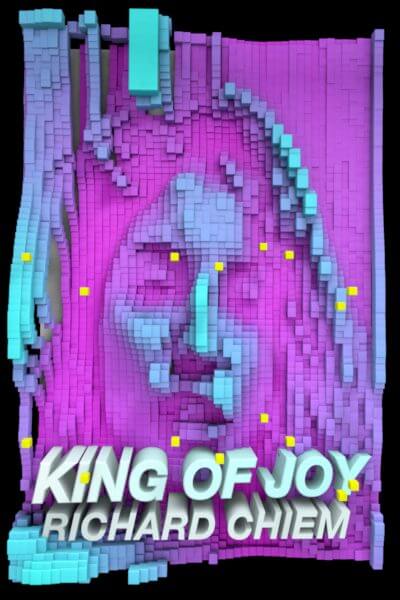

Corvus, the protagonist of Chiem's debut novel, King of Joy, at first resembles the classic Chiem character. Here she is waking up:

She doesn't remember what she dreams of anymore. It has been that way for years now, but it no longer bothers her. There is something peaceful in not knowing. Waking up without dreaming is like taking off a black mask.

Here she is after she's fallen into a life of human trafficking:

Sex becomes entering a room and leaving a room, pounding heartbeats on a schedule. Sex becomes muscle memory. After a few days, Corvus begins to find a rhythm in her new life. Her body surprises her, her mind continues to drift endlessly, and by each day's end she can hardly describe the way she feels. It is quite possible she feels nothing.

That last line: it is "quite possible she feels nothing," meaning she isn't even sure if she feels nothing or not. It's less than nothing. It's Schrödinger's apathy.

But Corvus employs that emptiness as a super power. If you're not connected to the world, she reasons, the world can never hurt you. There's an immortality in Corvus's passiveness:

Corvus lights a cigarette. She smiles at how scary it is here and laughs at herself. But she has always loved proving a point, that nothing will ever kill her. Nothing kills me, she thinks.

You might think that a 200-page novel about a young woman who is all but emotionally dead might be boring, or aimless, or as empty as its protagonist. You would be underestimating Chiem's considerable talents. There's an energy seething behind the words in King of Joy, an outrage and a demand for justice, that drives the story onward.

By deadening her every nerve, Corvus is surviving the world. It's a defense mechanism, a way to stay alive. The only question is if she'll survive long enough to find the essential person at the center of her being.

Corvus's world is an ugly one. Everywhere she looks, she sees people who are exploiting other people, and people being exploited by others. She can't walk down the street without encountering some bizarre sex act that seemingly nobody else can see:

On the walk home from school, on the other side of a chain-link fence, Corvus can see a man masturbating in a brick alleyway with another man watching. The other man is smoking something. They both wave at her and smile from far away. She can feel them waving and smiling at the corner of her eye as she treads uphill toward home.

It's kind of like a twisted version of Alice in Wonderland, where Corvus finds herself in a world where nobody is kind, where everyone exploits everyone else, where you must deaden your nerves to survive.

Fans of Chiem's work — people who've read his debut collection You Private Person, or seen him read in his signature deadpan delivery — will know what to expect. But even those familiar with his work will be pleasantly surprised by what Chiem does with King of Joy. This isn't a one-note story about a sad girl. It goes to some delightfully weird places.

Perhaps the clearest illustration of what I mean is a tacky island of pleasures, guarded by giant aquatic mammals:

Gigantic art structures come into view, and, along her walk, she finds garden mazes scattered throughout the property. Corvus imagines spending the rest of her life in this place, growing old, walking this strange island. The moonlight on the lake shimmers and draws her closer. She passes by a row of black marble dog statues, each the size of a Toyota Corolla...High on a marble land bridge, Corvus watches the hippos from a safe distance, and looks up at the moving blackness accumulating in the sky. It looks like rain and more.

Yes, hippos. And yes, car-sized marble statues of dogs. It's kind of like Xanadu, a paradise that kind of resembles the airbrushed dreamscapes you'd find on the sides of Trapper Keepers in the 1980s. Chiem doesn't overplay the absurdity of the situation, but he does allow it to infect the story, to inject a bit of life and, yes, joy, into Corvus's world.

I don't want you to think that King of Joy is anything like a recovery novel, or a morality play. Corvus carries a lot of heartbreak inside her, and she can't cast it off like a ratty old coat. But she can open a crack inside her self, to allow the world inside. Once you find those special places, those hippo-guarded islands that resonate with your soul, you can slowly come back to life again. Nothing is permanent in the wonderlands of Richard Chiem's mind — not even death.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound