The facing page

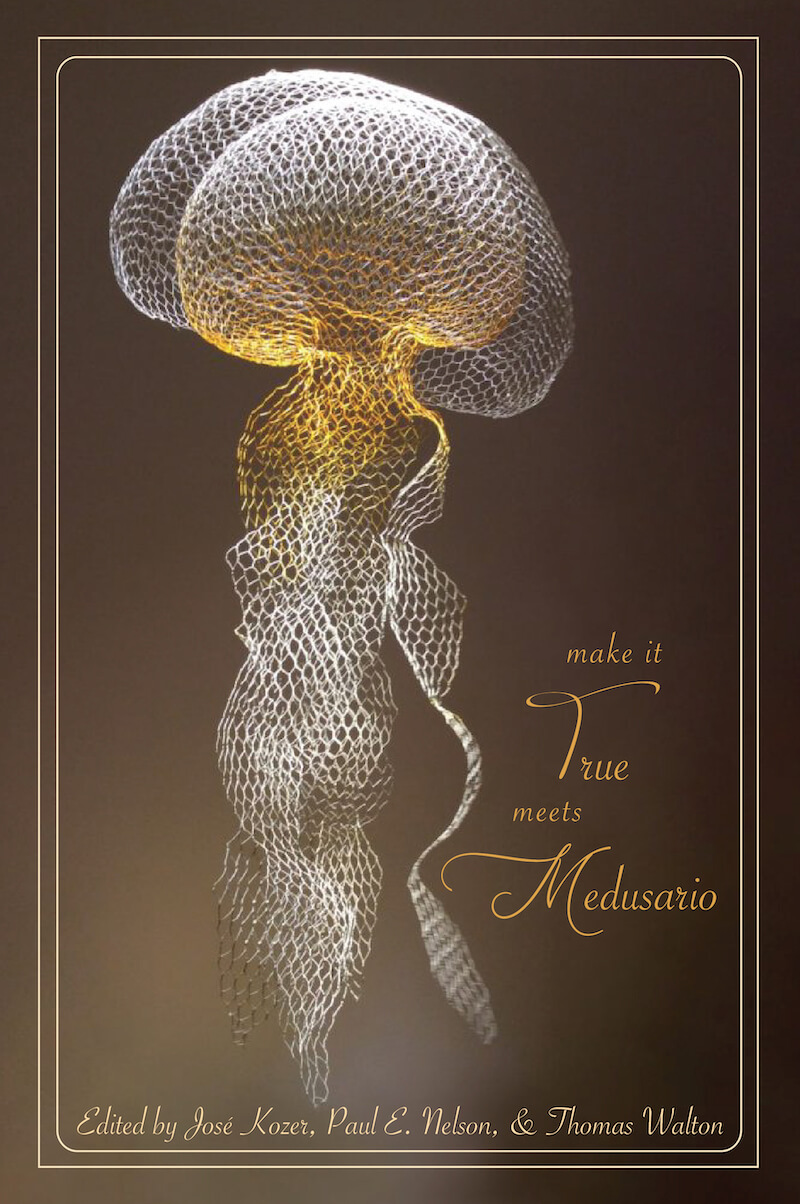

It might be nearly impenetrable to a casual browser, but the name of a Cascadian/Latin American poetry anthology published earlier this year, Make It True Meets Medusario, has quite a story behind it. In the introduction, Matt Trease explains that the book originated as...

...a bringing together of the poetry communities represented by two earlier antholgoies: *Medusario: Muestra de poesía latinoamericana* (Fondo de Cultura Econonómica, 1996), an anthology of Latin American Neobarroco poets that [poet José] Kozer had co-edited and *Make It True: Poetry from Cascadia* (Leaf Press, 2015), a bioregional poetry anthology of which [Seattle Poetry LAB founder Paul E] Nelson was a co-editor.

From the outside, the title sounds inscrutable, but flip to page ii of the introduction and it's as clear as noontime sun: A mashup, a joining of two cultures, a fusion of two poetic celebrations into one literary mega-party. Every piece of writing in the book is presented both in English and in Spanish. The poetry is presented facing-page style, with the author's native language on the leftmost page.

The pairing is, to be clear, not a one-to-one comparison. Even with the focus on neo-baroque poetry, Latin America is immense and contains an almost uncountable number of subcultures. Cascadia, as envisioned as a unitary bioregion by anthology co-editor Nelson, contains a number of native cultures and immigrants from all over the world, but is geographically much smaller.

But there's no reason to be symmetrical in a poetry anthology. That dissimilarity between the still-finding-their-voice poets of Cascadia and a decades-old poetic movement from Latin America makes the volume more compelling. One might hope that considering Seattle's newfound role as a UNESCO City of Literature, this anthology might mark the first in a series of poetic Cascadian explorations of regions around the world. Let's smash anthologies together with peoples from everywhere, just to see what happens!

And the happy news is that Meets doesn't feel asymmetrical at all. These works feel of a piece. Even works that are quintessentially Cascadian, like Sarah De Leeuw's "October Chanterelling—," with its warning to consider the "orangey gold stubs" of mushrooms "left in the ground for next year because everything grows on earth left/by something else," feels like it's deep in conversation with Carmen Berenguer's poem "Ode to My Hairdos", which begins:

I'm shedding hairs some straight and brittle others blades in the winds of suffering

sweetening oblivion moving dry and lifeless

stiff leaves in layers toward the peaks

torturous coming to my shoulders

No matter where you are, the dead and the brittle and the discarded is where life and beauty originates.

It makes sense that writers from these two regions should be interested in similar pursuits. The fact is that the world is small and, regardless of the efforts of a few reductive monsters like the President of the United States, getting smaller. Usually books like these tend to accentuate the familiar.

And sometimes the distance doesn't really exist at all. Nelson's poem "Juan Vicente de Güemes Padilla Horcasitas Y Aguayo, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo" addresses the Seattle landmarks with Spanish names. Nelson wonders, "y who is de San Juan after whom/de islas de San Juan are named?/& how did Spaniards/get here and who, why how/did the blood stop."

It's a pretty neat trick that Nelson employs here that I've never seen done in facing-page translation before: By beginning the English poem with "y," the Spanish word for "and," he ensures that the English poem begins with a Spanish word and that the facing-page Spanish translation begins with an American word. Nelson is forcing the reader to slow down and stop and reassess whether they're on the "right" side of the page. The established order of the book becomes questionable, and the borders between poems begins to blur.

But a few pages away, Nelson's co-editor, Kozer, undercuts that suggestion, noting skeptically in "Present Reader" that an old man assumes "that he and I belonged to/the same people because we/both spoke/Spanish." That's an assumption that has guided millennia of human development, and it's led to a lot of problems.

While Nelson wonders about colonialism, Pedro Marqués de Armas, in "(chronicle)," reflects on the sins of Latin America, beginning the poem with "the Chinese Man who was hung by his foot/in the small coves at San Lázaro," and a history of murder and suicide. (These are topics we understand well here in Cascadia, in our not-so-distant history.)

It's a true delight to read a book that is so furiously, excitedly in conversation with itself. Each piece feels like it springs from the page before, and that it inspires the page after, encircling the reader in poetic conversation. The facing-page translation is also facing the reader, insisting that they look the poets in the eyes, demanding an emotional response. Like every conversation, Meets requires you to give as well as take. That's the only way to live in this complicated world together in some sort of peace.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound