The must-read list

Most readers have a mental list of authors who have earned a spot on their must-buy list. You know what I mean: the writers of books that you'll immediately take out from the library without even reading the dust jacket copy. The ones who never let you down, or let you down only in interesting ways.

A few of these names have been on my must-read list for decades — James Morrow, Colson Whitehead, Jhumpa Lahiri, Aimee Bender, Neal Stephenson, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Stacey Levine. These are the writers I'll follow anywhere. (But like yours, my list is not immutable and favorites changes over time. Haruki Murakami, for example, has recently dropped off due to his apparent inability to recognize and grow beyond a strict quartet of recurring themes.)

Sam Lipsyte is a name that's been at the top of my must-read list for almost two decades now. His novel The Subject Steve, about a man who is literally dying of boredom, reaffirmed my love for literary fiction at a time when every prestige publication felt so same-y that new arrival tables at bookstores all felt like beige blurs of nondescript titles like The Cabinetmaker's Daughter.

Lipsyte's novel Home Land is the one that broke me — in the best way imaginable. Home Land is the cringe-tastic story of the one failure who never got over high school, and who plans on getting his revenge on everyone else for growing up. It's funny and bitter and ferocious in the best way, a love song to the misanthrope in all of us. With The Ask, Lipsyte accomplished the unthinkable: he wrote a novel about a washed-up university professor that didn't feel like wish-fulfillment for a midlist author.

Between all of those novels and his two short story collections, Lipsyte won me over with his language. Some humorists take a Gallagher approach to written comedy: they'll crush any sentence, character, or plot point when they're in pursuit of a punchline. But in the vein of Stanley Elkin or Dorothy Parker, Lipsyte's comedy thrums through every syllable of the book. The scenarios and satire of his novels are of course important, but he has the most fun with the language.

Lipsyte's outsized characters and premises provide opportunities for him to riff on words and sentences and rhythms — the books have plots, but really they're about those tremendous, ridiculous sentences. Here's a bit from early in Lipsyte's brand-new novel, Hark, from the perspective of a main character named Fraz:

Pickering, New York, once the largest manufacturer of frozen waffles in the country, has invited Hark to speak on the rudiments of mental archery. Near the town an ancient billboard juts from a cliff. Boys in earth-tone plastic helmets clutch honey-brown, frost-stippled discs. The tagline reads: GENTLEMEN, START YOUR TOASTERS. Fraz recalls this ad campaign from his childhood, though he remembers it as "Gentlemen, Start Your Waffles." Could the company have survived longer with his version? Fraz berates himself for foolish speculation, then berates his inner berater for stifling winsome or playful thoughts, for from such lazy perambulations through the noggin's grottoes profundity can effloresce — ideation's lush, dark bloom.

That is a lot of thinking about frozen waffles and washed-out America and the ludicrousness of advertisements and the inanity of undirected thought — but the paragraph would be entirely worth it for the word pairing of "noggin's grottoes" alone. It's such an ugly pairing, but so evocative: the wet and slurpy parts of the brain where good ideas go to die.

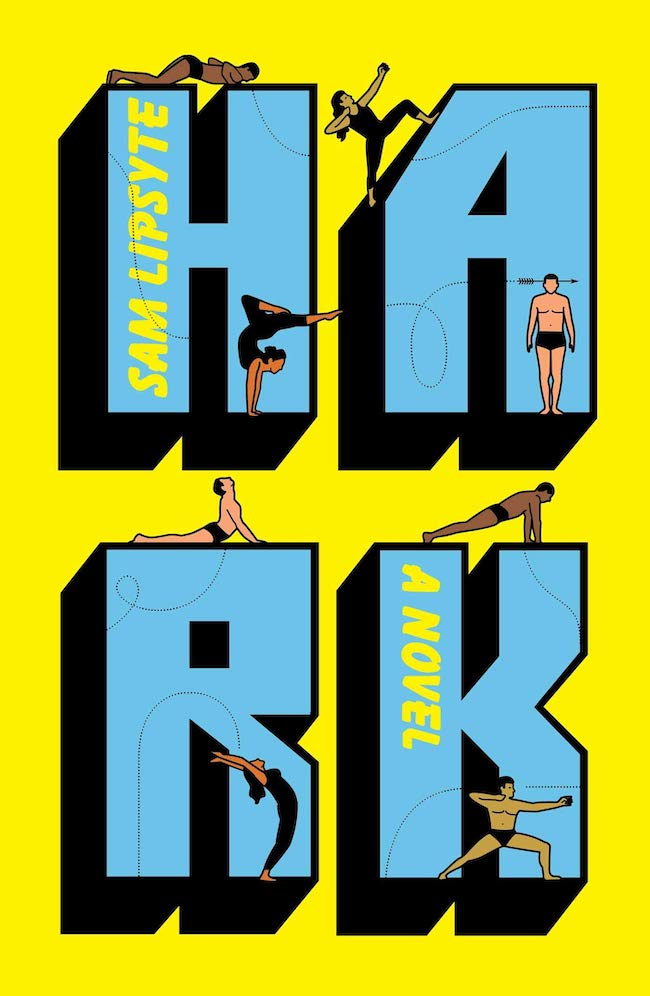

Hark is the story of Hark, a self-help guru who has perfected a style of focus-driven meditation called, as referenced above, "mental archery." None of Hark's followers ever pick up a bow or arrow. Hark reminds them continually that mental archery is "a metaphor." So instead, in order to foster a connection between themselves and the real world, an ever-growing number of people imagine that they're shooting a pretend arrow at a made-up target.

Hark is a book that absolutely belongs on your must-buy list. Lipsyte uses the premise as permission to make fun of — and to revel in — the weird and wonderful vocabularies which accompany subcultures ranging from the poetry scene to art museums to tech culture.

In many ways, Hark is a book that's entirely about focus. It's not a finger-wagging fusillade against the youth these days and their short-attention-span culture — more just a consideration of what it means to pay attention and what attention is worth. The disciples who fall for Hark's vague and pretentious teachings almost certainly enjoy better focus, but they direct that focus in an entirely wrong direction.

One of the darker running jokes in Hark is the recurring mention of world events. Wars are breaking out where there haven't been wars for decades. Things are getting weird and apocalyptic. But people only mention them, briefly, in passing, as if global destruction is a buzzing mosquito to be waved away in favor the real, important things. Those sequences almost feel like a parody of the way readers will enjoy Hark — in brief soundbites, between buzzing phone alerts of Mueller investigation updates and some new presidential contender and all the other awful banalities of life in 2019. A novel about focus feels, at this stage of the Trump presidency, like a cruel joke.

Ultimately, Hark doesn't know what to do with itself. A turn in the plot toward the last quarter of the book collapses the novel's comedic framework and accelerates the book's plot to an unpleasantly fast pace. It feels like Lipsyte knows roughly where he wants the book to end, but he can't quite get there.

Still, that's the thing about writers on the must-read list. Certainly not every one of their books can be perfect dispatches from a heavenly realm of blessed creativity. But you develop a trust in them and their work, and you understand that even if you don't like where they take you, the journey will definitely be worth it. I'm riding with Lipsyte until I die.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound