The pleasure of addressing

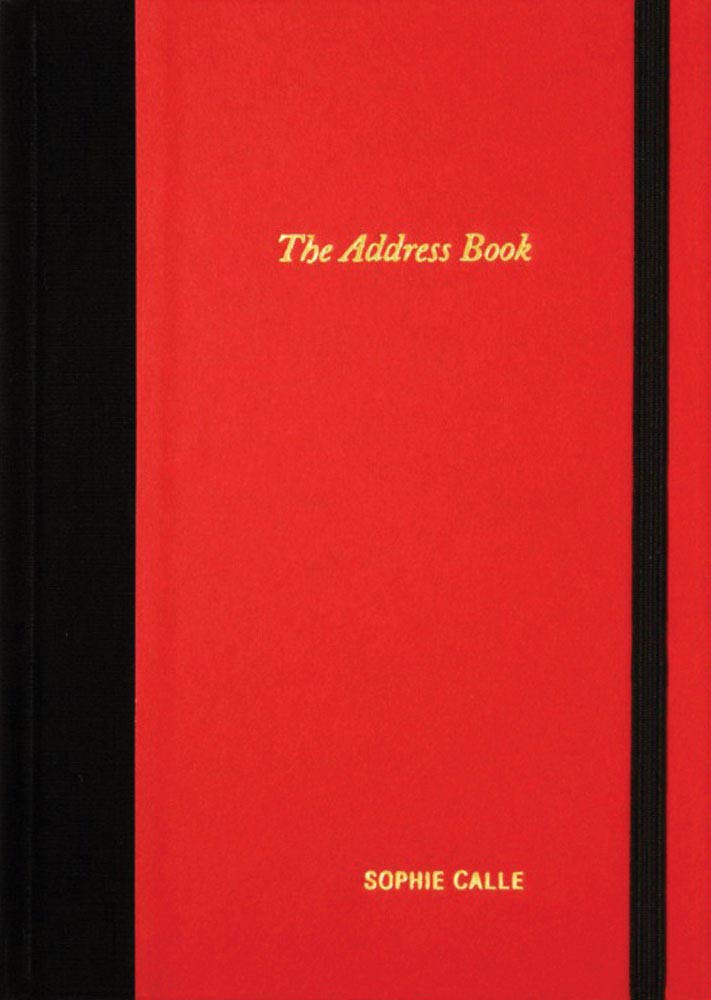

In the summer of 1983, Sophie Calle found an address book on the street, on the Rue des Martyrs. To someone without French, or any knowledge of Parisian geography, this is suggestive in the way that only ignorance allows. On the street of martyrs, Calle found, or made, a martyr of her own.

Before she sent the book back to its owner, “Pierre D.,” Calle photocopied it. Over the next months, she called the phone numbers found on those copied pages and sat down with anyone who agreed, asking them how they knew the address book’s owner and what they knew of him. She published the briefest of essays on each encounter, one by one, in the magazine Libération. Later, they were collected in The Address Book, along with a series of artlessly coy photographs.

It’s easier to understand this magnificent invasion of privacy if you know that Calle is a performance artist as well as a writer; that is to say, someone for whom reality is art not only on, but off, the page. We’re used to the casual betrayals of the writer, from Lowell to Knausgaard. But art’s betrayals are more comfortable, somehow, when bled through the medium of ink.

“I will get to know this man through his friends and acquaintances. I will try to discover who he is without ever meeting him,” Calle writes. Today, we make such explorations from behind the veil of a search engine. Calle is braver than we are. Though not so brave. Even Calle balks, a bit, at what she plans; calling the first number, “I put it off, I hesitate, I dial, I hang up.” She decides to call Pierre D. instead. His answering machine. She visits his neighborhood. She — stalks — him, we would call it now, or would call it if their genders were reversed.

Finally, she calls, and someone answers, and then another someone. A few turn her away; those closest to the address book’s author, and those most introverted, most protective of their own anonymity. Because, of course, everyone who chooses to betray Pierre D. is betrayed by their own openness. Seen on the pages of Libération: Sylvie B. knows what’s on the ceiling above his bed. Monsieur Baaron, an actor, assumes the contact is a trick to enter his confidence. Theirry L. wears Calle out with his enthusiasm for his subject. (Poetic justice?)

And also: seen to the world and to Pierre D. as someone who would open to door to an acquaintance’s invader. One close friend meets with Calle, but reluctantly, as if fulfilling an unwelcome obligation. Another shouts at her violently over the phone. Calle decides not to contact Pierre’s father after that, afraid of his response.

What do we learn about Pierre D. through Calle’s conversations? He is interested in film and both knowledgeable and theoretically adept in discussing it. He is obsessed with Egypt. He is attractive in the abstract but not, apparently, actionably so. He loves women but fails often in love. He has prematurely white hair, possibly brought on by his mother’s death. He keeps, in his address book, the names of people who do not remember him. Does he remember them?

The photographs: let’s talk about them for a moment. Intentionally, annoyingly coy: the address book; a pair of empty chairs; a woman’s, or a mannequin’s, high-heel-clad foot; a marble bust to suggest Pierre’s whitening coiffure. A polar bear! Pierre D. sends postcards, and the bear is suggested by an interview with Jacques D., who received just such a postcard from him. Pierre D. has been to Norway. He has been to Venice and Rome. He has produced a television show about Jerry Lewis. All of this comes perhaps through a single word in an interview, but is magnified into significance by the camera’s lens. Not even the same polar bear!

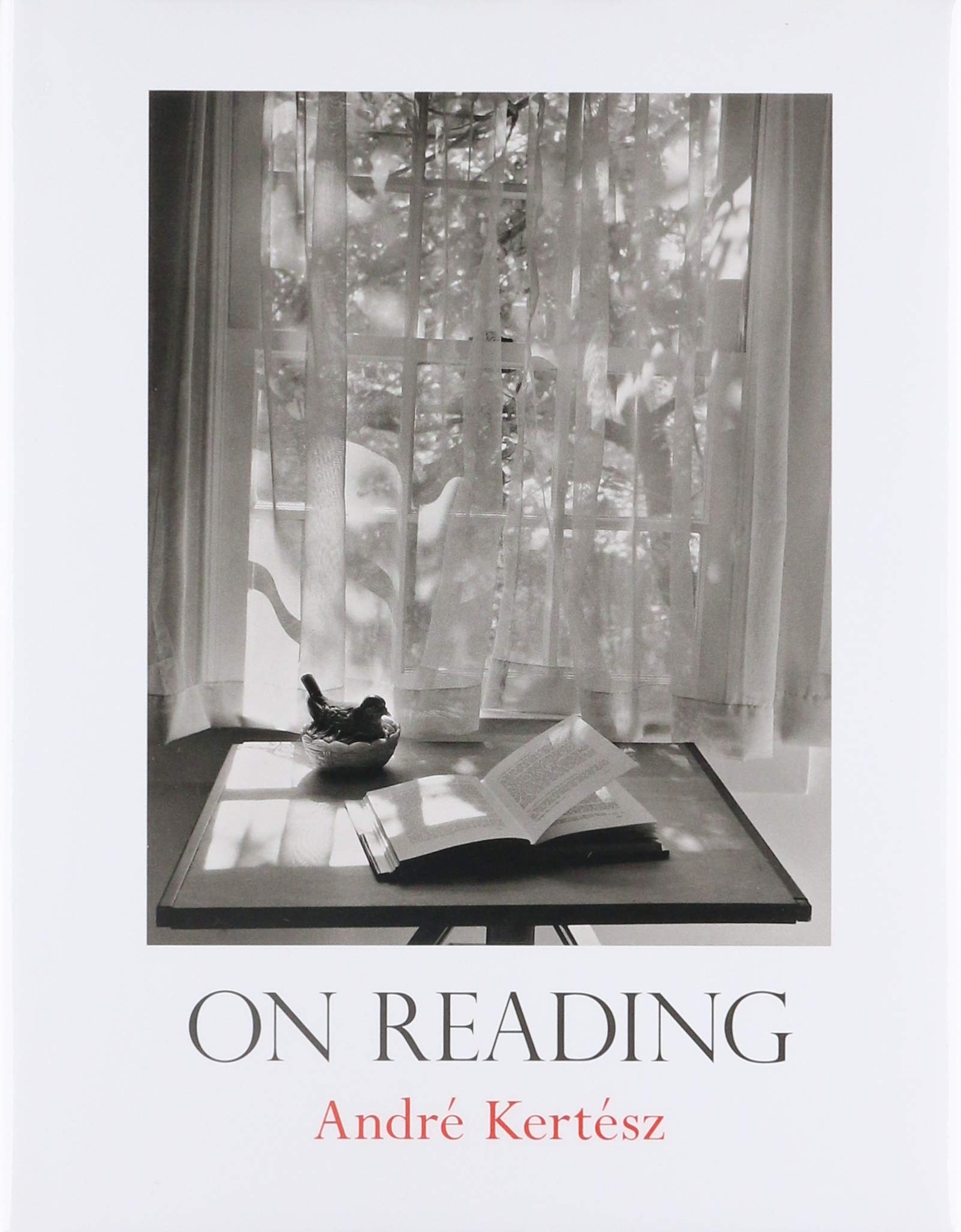

Step, for a moment, outside The Address Book and into another: On Reading, a collection of images by the Hungarian photographer André Kertész. Deeply intimate, these photographs should be intrusive — invasive. They capture readers in the most intimate act possible (no, not that one; the one that involves paper and ink). An old woman reading in bed, a boy sitting on a pile of newspapers, reading comics and eating an ice cream bar, a series of readers on New York’s balconies and rooftops. Alone in the world of their books, they have left their own images unprotected, and Kertész steals them.

But what we see through Kertész’s lens is privacy not violated but preserved. The back of a young woman’s neck, under a bonnet, as she leans over her book on a stoop. An unidentifiable person sitting L-shaped in the woods, among the leaves, among the trees, again, alone. Perhaps my response is simply a reader’s love for other readers — but you sense an affectionate confidence in these photographs, respect, even admiration.

It is no criticism of Calle to say that her book feels more like an act of intrusive, self-serving curiosity. What could be more banal than to accuse an artist of behaving selfishly? Or of intruding on another’s privacy in the service of their art? No: what’s interesting is not the accusation, but the dance. It’s Calle’s obvious discomfort, and how she hides it inside the camera and by what she chooses not to share from the interviews she conducts. Pierre is alone, even lonely, say many of his acquaintances, directly or by implication. Calle has little to offer the lonely man.

Perhaps — perhaps the loneliness her interviews reveal in Pierre is the loneliness that would be seen in any of us, if you spoke to our acquaintances as a stranger. Perhaps that is why Calle continues (that, and her deadlines), as her uneasiness grows. Because to stop would be an acknowledgment that Pierre’s disease is simply being human.

“Suddenly, I am afraid of what I am doing,” says Calle.

“But I must continue.”

Dawn McCarra Bass is associate editor at the

Seattle Review of Books and co-director of the Pocket

Libraries program, which channels high-quality donated books to

people with limited access to reading. By day, she’s the founder

of Mightier, a small

consulting firm where women solve problems creatively, collectively.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound