The promise in your pocket

Right after the debut of the iPhone, we all went a little bit mad for tech. It was like the whole country was swept up in a wave of Apple's promotional hype, and we never thought we'd touch land again.

Or maybe I'm half-assedly covering for myself by making a broad statement about the general population. I'll admit that my tech writing, for a good four years after 2008's iPhone launch, was insufferably credulous. For a time, I believed that consumer technology was somehow going to fix everything that was wrong with America. I thought that technology was the solution to all our ailments, that phones and laptops and gadgets would keep improving exponentially, and that eventually everything would be better, thanks to our Silicon Valley overlords.

I believed in tablet technology as a cure for journalism's ailments. I believed that self-driving cars would end urban gridlock. I believed that cellular phones, somehow, would lead to individual empowerment and an array of creative pursuits. If you asked me back then, of course, I wouldn't have admitted to any of this. But at some level, deep down, I bought into all of it. I was a true believer.

Not only was I wrong on every one of those counts, I had it all entirely backwards. The tech industry caused journalism's decline. Cell phones were eating our identities, piece by piece, and regurgitating them on social media. Self-driving cars were a lie that urban leaders told themselves when ignoring the symptoms of climate change and traffic over-saturation.

What I really needed at the time was a pair of clear eyes — the ability to see past Steve Jobs's famous "reality distortion field" and recognize the scam for what it is. And don't get me wrong: I'm not saying that Silicon Valley is a grand conspiracy against our humanity. I just think it's a collection of people with too little common sense and too much money running around with too little regulation. Under those conditions, bad things tend to happen.

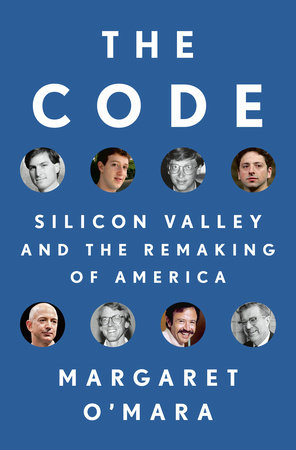

University of Washington professor Margaret O'Mara has written a book that helps to contextualize that moment when everything changed into a new status quo. It's called The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, and it's an immense history of the origins of Silicon Valley and how that culture still shapes us today.

O'Mara's book isn't a hagiography of our new plutocratic tech-lords, but nor is it a Jaron Lanier-like excoriation of tech culture. Instead, it's a serious and sweeping investigation into the forces that shaped Silicon Valley, and an exploration of how those forces continue to shape us today.

How sweeping is it? Chapter three begins with the launch of Sputnik and then O'Mara, beautifully, uses the satellite to check in with her main characters, who are spread all over the country:

By the time news of the launch hitAmerica's Saturday morning papers, the satellite was on its tenth orbit, soaring more than five hundred miles above the Hudson River Valley as Ann Hardy was having breakfast at her kitchen table in Poughkeepsie. Seconds later, it flashed over Boston as Vannevar Bush puffed on his pipe in his book-lined study. By its eleventh loop, it was well past Cleveland, where thirty-seven-year-old David Morgenthaler was raking early autumn leaves and thinking about the big new job he would start in a few days...

It's a beautiful and audacious literary device, and it continues for a while, gliding at 18,000 miles per hour over cast members in Texas and New Mexico and California and Washington.

About those names: you might not recognize any of them. In fact, many of the most prominent figures in The Code are nobodies to the general public, but their influence continues to shape our world in thousands of ways every day. This is not just the province of Gates and Bezos and Zuckerberg, though they are in here, too.

It all could have been hugely different. Silicon Valley was always roiling with a war between the profiteering data freaks and the free-use pirates — between open source and closed systems. Many of Silicon Valley's earliest pioneers, O'Mara writes, were obsessed with Ivan Illich's demands that "We now can design the machinery for eliminating slavery without enslaving man to the machine."

That blasé use of "man" to stand in for "humanity" is indicative of the way that Silicon Valley developed itself as a place that is downright hostile to women. All the ads for computers, including an early Apple computer advertisement, featured women in supportive, quiet roles. Though women were present at the very beginning, they soon were forced out of the portrait in a very aggressive way — and then the victorious men set about designing hiring and employment practices that excluded women.

And while ideologies were at war, the federal government made it all possible thanks to a vast array of grants and commissions and investments and deregulation. Those who like to think of Google as something wholly independently created in a garage might be alarmed to learn that it takes a village - in fact, it takes a whole military industrial complex — to raise a hundred-billion-dollar company.

You've heard many of the stories you'll read in The Code, but you've never heard O'Mara tell them, and that makes all the difference. When viewed from end to end like this, the myth of Silicon Valley seems less like a miracle and more like a plucky scam perpetrated by confidence men who saw their one opportunity and seized it. It paid out in a huge way for them. The rest of us are still slowly coming to the realization that maybe, just maybe, we've been had.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound