The sky is falling

Zombies, zombies everywhere. Who the hell isn’t a little sick of zombies at this point? Even people who love carnage and a little fictional gunplay ought to be getting sick of zombies by now, right? You can stretch the metaphor like a wad of chewing gum — the zombies stand for consumerism, or they represent our germ-phobia, or they represent our self-loathing — but eventually that thin pink strand is gonna break. We’re getting zombie’d out as a culture.

The big problem with our zombie obsession s that as a plot point, zombies are not clever. In fact, they don’t do anything. They don’t plan, they don’t show emotion, they’re not crafty, or sly, or evil, or angry. As antagonists go, they’re less intelligent than your average bear, and twice as easy to understand. All they want is brains. Braains. Braaaaaains. It’s goddamned tiring, is what it is. All respect to Robert Kirkman and Charlie Adlard, but the Walking Dead — the ongoing comic, not the TV show — only stayed interesting because it turned the zombies into scenery and focused on the humans. Kirkman understood that there’s only so much tension you can wring out of a thought-free foe, an ambulatory venus fly trap.

Nope, give me an alien invasion any day. The risk for silliness is much higher with aliens than it is with zombies, but the potential payoff is much higher, too. With aliens, you have all sorts of questions of motivation (Attack the Block was especially clever with that) and technique. You know what you’re going to get with a zombie, but alien invasions have all kinds of unknowables in their favor. A good alien invasion narrative is full of all sorts of unknowns, and good fiction should, really, be all about the unknowns.

The reason why I’m going on about all this is that I’ve just finished what is almost certainly the best genre comic book I’ve read all year. Even more extraordinary: the best genre comic I’ve read all year was published by Fantagraphics Books, the Seattle-based publisher of literary comics. It’s titled The Eternaut, it’s written by Héctor Germån Oesterheld and illustrated by Francisco Solano Lopez, and it’s considered a classic in Argentinian science fiction. Originally published in a weekly format between 1957 and 1959, The Eternaut has never before been published in English (Erica Mena did the translation, and though I can’t compare it with the original text, the language feels smooth and sturdy). Published as it is in a stylish slipcase/clear dust jacket/chromed die-cut book cover combination, Fantagraphics delivered The Eternaut as a slick, stylish package, but the elaborate packaging only begins to hint at the thrills you’ll encounter once you finally start reading.

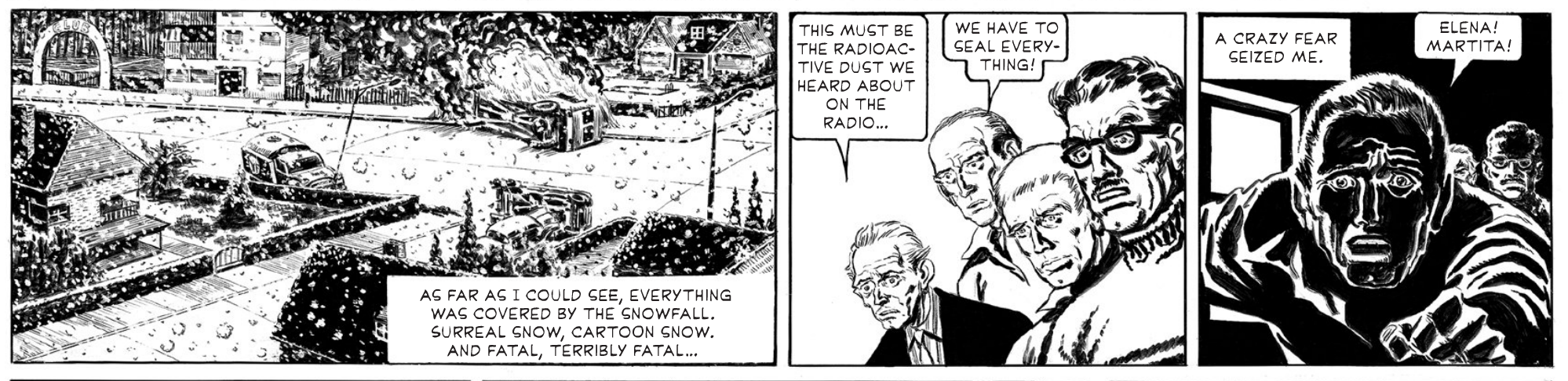

The Eternaut is the story of Juan Salvo, a seemingly normal resident of Buenos Aires who’s hosting a night of card games with his friends. Suddenly, the sky fills with snow — a rare enough sight for Argentina. Worse, the snow seems to be poison; it kills every person who comes into contact with a single flake.

Obviously, The Eternaut is crammed full of Cold War-era paranoia. (Nuclear winter is alluded to early and often in the first few pages, even as Salvo and his friends dismiss the idea relatively quickly.) But this isn’t the heroic Cold War narrative of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s Marvel Comics. Instead, it’s a more passive, powerless Cold War perspective; a story told by a bystander in the battle between the US and the USSR. All Salvo can do, at first, is watch, and worry. Soon, though, a course of action becomes clear. One of Salvo’s best friends, Professor Favali, proves to be a kind of apocalyptic adept. He can instantly determine the best course of action for any eventuality, and soon enough he and Salvo’s family are constructing wetsuits to protect the men as they head out into the deadly world to find supplies.

I don’t want to give away too many of The Eternaut’s secrets. Not that this is a book that can be spoiled, really — the journey is the destination, here — but because the twists are practically besides the point. What matters is that Oesterheld and Lopez keep the narrative in the air for almost 400 pages, continually throwing new threats and obstacles in Salvo and Favali’s way.

The story is rife with cliffhangers and new foes, but everything hinges on a single question: what the hell is going on? Every other question springs from that: Is this an alien invasion, or some kind of a trick? If it’s an alien invasion, what do the aliens want? Who’s, really, in charge here? Will our heroes ever figure it out? Is understanding central to their survival? Or is surviving really all that matters?

Fans of modern comics, with their tendency to opt for a huge splash page at every opportunity, might find The Eternaut takes some getting used to. The story is told in black and white and it’s laid out horizontally, in the small rectangular panels we associate with comic strips. But once the story starts to pull you in — really, that should happen as soon as the inky skies start vomiting forth toxic snowflakes — the panels fall away to reveal a broader stage. Lopez fills every panel with exactly as much as it can bear. Sometimes it’s just Salvo’s shocked face as he processes some new horror. Other times it’s a line of anti-tank guns, or an empty soccer stadium repurposed as a military base. The scale varies wildly, and Lopez’s art can handle every bizarre concept that Oesterheld throws his way.

Lopez’s art is reminiscent of the “realistic” work of EC cartoonists like Wally Wood. The Buenos Aires that he depicts here, lined with the anonymous bodies of the dead, is obviously his home. What appears to be real architecture of the time stands behind scenes of carnage — a bus turned on its side, say, every passenger inside murdered by the deadly snow — adding a more palpable sense of horror to the proceedings. It’s easy to imagine Lopez walking around his city with a sketchbook or a cheap camera, imagining what the lively streets would look like strewn with bodies and horrific monsters.

Like most serialized genre storytelling, some will find fault with The Eternaut’s ending. It’s a fair complaint, but it must be said that even Dickens had difficulty sticking the landing more often than not. I, for one, admired Oesterheld and Lopez’s willingness to stick to their theme through the very end. If The Walking Dead manages to end, one day, with half as much grace and class as this, it will be nothing less than miraculous.

Reading The Eternaut makes me wonder how many other translated comics masterpieces are out there waiting to be discovered. It’s a universal story, told at the neighborhood level. Salvo and Favali aren’t leaders of men, and they know they can’t save the world by themselves, but they keep struggling against impossible odds. As they try to understand the horrific new world unfolding around them, they see hints of larger mysteries expanding beyond the horizon. Some of the mysteries will never be solved, or even acknowledged. They have to content themselves with this understanding, and it’s that knowledge — that they are dealing with forces beyond their comprehension and control — which makes them heroes.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston's grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle's own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound