The visible woman

Artemesia Gentileschi is having a moment right now in the Pacific Northwest. The Renaissance painter was featured in Blood Water Paint, a Washington State Book Award-winning book-length poem for young readers by Joy McCullough. Blood Water Paint was also adapted into a play at 12th Ave Arts on Capitol Hill earlier this fall. And Gentileschi's work is on display downtown at the Seattle Art Museum, as part of the Rlesh and Blood: Italian Masterpieces from the Capodimonte Museum traveling exhibition.

It makes sense that Gentileschi should enjoy a revival in the current moment. Many of us are looking at the whiteness and the maleness of the artistic canon that has shaped culture and for the first time seeing all the women and the artists of color who have been ignored and left outside the walls of institutional power. It's a story of empire told entirely in negative space.

Too many artists have disappeared entirely — their work devalued, ruined, and lost forever because male scholars deemed it inessential. But enough physical examples of Gentileschi's work have survived that we can see she stands alongside the other baroque painters of the Renaissance — and, in fact, her work often surpasses those of her male peers. She has earned our attention with her work, but she also represents all the artistic geniuses we never got to know because of their gender. How many Gentileschis have been scrubbed entirely from the record? We will never know. And so we hold Gentileschi close.

So this newfound obsession with Gentileschi makes great sense to us. Not only is her work brilliant and haunting, but her life story is incredibly compelling. She was a single mother at a time when that was not acceptable, and she survived sexual assault, public shaming, and multiple total devaluations of her personhood at a time when women were not allowed to make even one mistake without being punished for it. Through it all, Gentileschi not only survived, but she thrived.

Here in Seattle, though, one cartoonist has been way ahead of the curve. I first encountered Seattle cartoonist Gina Siciliano's obsession with Artemesia Gentileschi on March 11th of 2015 at the Cornish Playhouse at Seattle Center. Siciliano was presenting a piece of what she projected to be a book-length comic book biography of Gentleschi, and pretty much everyone in attendance could tell that something special was happening.

Siciliano's devotion to Gentileschi's story felt almost monklike, as though she had dedicated her life to the elder artist in a kind of religious supplication. She made near-perfect reproductions of Gentileschi's paintings in ballpoint pen. She did boundless research. She was as conversant in Gentileschi's life as just about anyone on the planet.

I watched Siciliano present her work in stunning black and white, projected on a large screen at the front of the house. There's something to comics art created with a ballpoint pen that feels more vulnerable, somehow. The lines are less exact than a more traditional inking pen or a stylus, and scratchier. This makes the art look like a handwritten letter, or a journal entry, or a book written entirely in longhand. At the end of the show, I bought a self-published collection of the book from Siciliano. It was probably going to be about three issues, she told me at the merch table after the show, but she wasn't sure how long it would take to complete it.

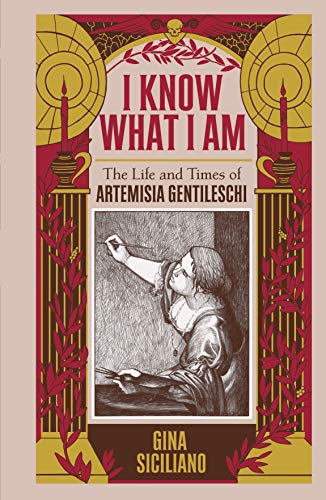

Earlier this fall, Fantagraphics Books published I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemesia Gentileschi by Gina Siciliano, in a gorgeous hardcover edition. It's a dense book, larger than most graphic novels, with a huge reference section in the back showing all the research that Siciliano did for the book. On the whole, minus Fantagraphics' continuing excellence in production value, the book looks largely the same as the first one that I bought from Siciliano four years ago. The most noticeable difference might come in the captions and word balloons: while the original series featured Siciliano's handwriting on every page, the new collection has been re-lettered and it's now much easier to read. (Siciliano's handwriting in the original book wasn't bad, but anything short of perfectly accessible lettering in a comic is an invitation for a reader to quit reading entirely.

What Am isn't just a comics biography of an artist who is finally, centuries later, getting her due. It's also a scholarly work on a great woman in history, a significant piece of art criticism, and a tribute to the creative process and the way it summons creators — not the other way around.

"You could be great," a man tells Gentileschi early in What I Am. He's looking down at her, and he's grabbing her arms, which look small in his giant hands. You can tell he thinks he's being charitable and generous and inspiring, even though it looks like he's mugging her. In the next panel, the man and another man who's looking on stare at Gentileschi, smugly smiling. She pushes them both away in the next panel, her face pinched up in disgust.

"I will be great," she says, as she fends them off. In the next panel she stands, her shoulders tight and her hair flowing free as she wields her paint brush and palette with the same enthusiasm that a superhero like Thor brandishes his hammer. Finally, she finishes her thought at the end of the page: "But not if you keep distracting me."

Gentileschi is forceful and powerful and strong-willed, but the people will not let her be. Later in the book, a crowd discusses her work. "I heard she's the best lady painter that ever lived," one anonymous person tells another, probably not even noticing the subtle condescension of putting the word "lady" in front of "painter." Another asks, "But where is her husband?" Over in the corner of the crowd, things get salacious: Someone blurts, "I heard she paints naked women!" Someone else replies, "I heard she's a slut."

Gentileschi is put on trial, both literally and figuratively. She loses friends to monstrous men. Her work is always ignored and diminished, though several patrons provide her with a means to keep making work. She has no other choice. She has to keep going.

And that's true of Siciliano, too: She managed to stake out an artist who meant the world to her, and then she dedicated herself to telling that artist's story. A long time ago, she was a young artist showing ballpoint pen illustrations to strangers, and now she's a published cartoonist with one mammoth book to her name already. Gentileschi never quit, and Siciliano won't either. For them, we should be eternally grateful.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound