Thinking through the clutter

I think about The Dukes of Hazzard every day. I have for as long as I can remember.

The show last aired in 1985; I haven't seen a single frame of it for twenty-five years. It is not in any way an active part of my life. Yet there it is, every day, popping into my head. There's no obvious trigger and no reason for it.

And it's far from the only bit of cultural or biographical detritus that clutters my thinking on a daily or near-daily basis. It's how the mind—non-linear, obsessive, flighty, inexplicable—works. Spider-Man, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," James Brown, the sweaty guy from the Pizza Hut in my hometown, George Eliot, Davy Crockett, Super Mario Brothers—I could keep going a long time before I ran out of topics.

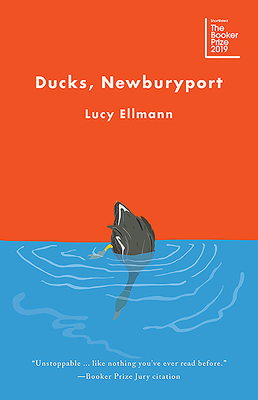

Or, to pick a number: 998 pages. That's how long Lucy Ellmann's novel Ducks, Newburyport is, and that's the stuff it's full of. Crucially, however, that's far from all it contains, and its aims are far higher than listing ephemera. Ellmann is attempting to represent how thought works in a single human mind. The length is headline-grabbing, as is the fact that the book is (more or less) a single sentence. But both of these devices are deftly used tools, rather than the core of Ellmann's achievement: to convince us that we are experiencing the life of a middle-aged Ohio woman from the inside.

A well-written book review deploys carefully selected quotations to highlight the author's style and insights. And I have those: “the fact that one good thing about having four kids is I never have to criticize them, because they do it for me” “the fact that when I do have any excess energy, I like to spend it being regretful and embarrassed” “hope indistinguishable from intent.”

“if aliens come

they will never stop laughing

at our sci-fi movies

they will never let it drop

But far more important is giving a sense of the actual experience of reading the book, which can best be done by sharing a longer passage:

the fact that Ben doesn't feel well, the fact that it's probably too many poffertjes, the fact that he's sitting quietly, on the iPad, _using_ it, I mean, not _sitting_ on it, the fact that _Oliver!_ was all Jill Worth's older sisters' idea, whatshername, the fact that she seemed much older than us and I never liked her very much, the fact that she scared me, the fact that, when you think about it, putting on a whole outdoor neighborhood production of _Oliver!_ was a pretty ambitious summer project for a teenager, the fact that she and her friends were really gone on _Oliver!_ so they forced us to act it out all summer, the fact that all _I_ had to do was sit on the grass playing solitaire, the fact that I wonder what became of her, the fact that I can't even remember her name, the fact that she was sort of a Hillary Clinton type...

You get the idea. Only, you don't. The extent is part of the effect. If Ducks, Newburyport were a short story, or even a slim novel, it wouldn't work the same way. What in a short story or a compact novel would have seemed a gimmick is transformed by Ellmann's commitment into a compelling aesthetic choice—a choice that then all but disappears under its own cascade of convincingly developed thoughts. What we get from Ducks, Newburyport is the mind in isolation, talking to itself and only half-listening to itself. After ten pages, we've settled in. After a hundred, we're engaged. After five hundred, we find ourselves forgetting that this is fiction.

The narrator is in many ways isolated, left to the thoughts Ellmman makes us privy to. She works from home as a baker, her husband travels often, and her kids are at school. Yet even a mind in isolation is far from truly separate. The stuff of which it's built is fundamentally social. The melange of memories, plans, worries, references, and name-checks Ellmann presents from inside her narrator's head is inextricable from the rest of the world, from family interactions to business exchanges to the processing of the daily torrent of news.

I've never read a novel that so accurately depicted the sensation of living in an environment where every day brings fresh horrors that don't directly impinge on our lives, even as they gnaw at our well-being. More powerfully still, I've read nothing that so thoroughly acknowledges the toxic mix of guilt and dread that is the bassline of life in Western society amid a climate change disaster that our every action exacerbates.

A writer like Jonathan Franzen harrumphs about The Way We Live Now, and shows us contemporary problems through situations built and floodlighted to showcase them. Ellmann is at her best when she shows how those problems are the dry rot of our souls, ever-present and all but impossible to extirpate. Ducks, Newburyport succeeds as the big social novel of our time, even as it is disguised as a big antisocial novel.

That inner monologue isn't the whole of the book. The run-on is broken up at multiple points by a different, non-human narrative, composed in more conventional sentences. It is a story of an endangered lioness raising, losing, then searching for her cubs throughout America's ever-shrinking wild spaces, a search that frequently brings her into close, confused contact with humans and their inexplicable creations. It serves as a mirror to Ellmann's human story (which offers its own concerns about parenting) and as a running commentary on how humans disrupt ecological relationships. It's an undercurrent to match the drumbeat of environmental concerns in the main narrative. But it's not always successful: within the main narrative, those themes remain subtle, because they feel like they emerge organically from the narrator's thoughts. The interpolation of the lioness's story, because it interrupts the flow we've settled into, can't help but always feel deliberate, its themes explicit, in a way that I am not convinced always adds to the overall effect.

The other weakness of the novel is perhaps inevitable. How is one to bring a book that largely mimics the endless run of thought to a close? The ideal would be to simply leave off, giving the book no more shape than that of the time period it covers. To do so, however, would be to court failure. Most readers would be irritated if a novel this long didn't seem to get anywhere. While I would happily make a case that getting to know the narrator's life and history is sufficient reward for our investment of time, I wouldn't expect to find many supporters.

Instead of taking that tack, Ellmann allows a plot to emerge. She does so about as well as possible within the narrative limitations she's set for herself. It's just that… I didn't want it, and—perhaps because of that—I didn't quite buy it. After she had earned my trust for so many pages, had surrendered so little to formal expectations, I was frustrated to have the conclusion turn on an unlikely event.

Yet the achievement remains. We read so many novels that are forgotten before we put them back on the shelf. So many 280-page stories told in the third person about relationships and contemporary life. So many Franzen-esque novels that lie inert on the page, hog-tied by their convictions and concerns. To read a novel that feels so fresh, that succeeds in putting the inner life on the page in a way that I've never seen before, is unforgettable. Ducks, Newburyport is the novel of the year, the one I'll be sharing with friends, talking about, and—like The Dukes of Hazzard—thinking about years and years and years from now.

Levi Stahl is the marketing director of the University of Chicago

Press, the editor of The Getaway Car: A Donald E. Westlake

Nonfiction Miscellany, and coeditor of The Daily Sherlock Holmes. He tweets, mostly about books.

Follow on Twitter

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound