What am I?

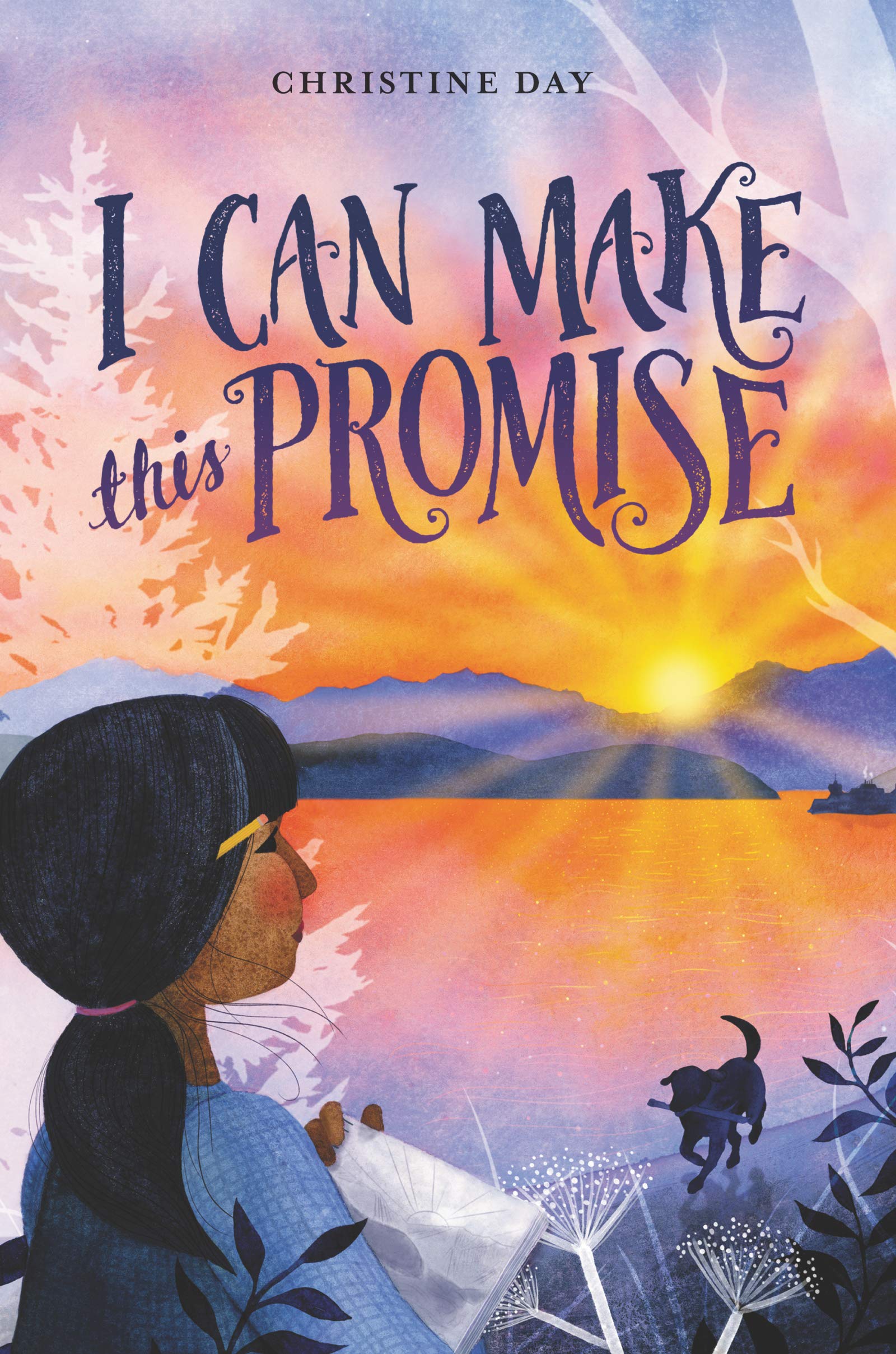

Edie, the 12-year-old hero of Seattle author Christine Day's debut middle reader novel I Can Make This Promise, cuts straight to the big questions. Early in the novel, she asks, "What am I?" It's a question that she has fielded her entire life from rude adults and nosy classmates who notice her dark complexion and demand an explanation out of her.

In response to the question, Edie explains herself to herself like this:

My father is American, and my mother is Native American.

Technically, Dad has roots in Germany, England, and Wales. But I don't mention this, because it feels dishonest. I've never visited these places. I don't know much about them. I'm not even sure where they are in the European continent.

So I just say Dad is American. Which works out fine because no one asks about him anyways. They jump straight to Mom. They want to know what it means to be Native American.

They ask me what tribe I'm from. They ask if I know what buffalo tastes like. They ask about my spiritual beliefs. They ask about the percentages and ratios of my blood.

My answer remains the same: "I don't really know. My mom was adopted."

The insinuation is that the questioners are placated by that answer. It's an interesting tactic: Edie counters a deeply personal line of questioning by offering up a related, but separate deeply personal truth. The word "adopted" in this case serves as a stone wall for the conversation, an unknowable past hidden behind a veil of secrecy.

But Edie is starting to be personally frustrated by that brick wall. She wants to know more about herself, her history. Like any child on the edge of the teen years, those questions of self aren't as easily answered as they once were.

Perhaps more than any other category of fiction, good middle reader novels tend to excel at providing gentle but unyielding answers to some of the complex problems of adulthood. Good adult fiction stares ambiguity in its face; good middle reader fiction suggests that ambiguity exists in the world, and makes the reader feel safe enough that they're willing to pursue it on their own time, at their own speed.

As a character, Edie is achingly familiar. She's just gotten braces, and one of her best friends is slowly detaching herself as she pursues a cooler peer group. She's starting to chafe at her parents' supportiveness, which has begun to feel alarmingly too much like coddling. Their inability to discuss Edie's biological grandmother feels more and more like a personal slight, and when Edie discovers a box full of decades-old personal effects from a woman named Edith who looks just like her, she begins the transgressive act of learning about herself.

Written by a Northwest author and set in and around Seattle, I Can Make This Promise is especially meaningful for Seattle readers. Edie learns about Native Northwest culture and history in clear and compassionate language, providing curious readers of all ages an opportunity to pick up some of the basics that they were too afraid to admit they never learned.

I Can Make This Promise explains all this and more, plainly revealing some of the darkest and most shameful moments in modern Native American history. It's not a fairy tale, but it's not a funeral dirge, either. Edie has an intrinsic joy, and her parents demonstrate a deep and abiding love for her, that provides a safe and nurturing environment for these truths to be shared with children. It's a disarming honesty.

This is not to say that the book is all about history. Day can write a spectacular meet-cute moment, too. There's an instance early in the book when Edie meets a boy who's holding a lit roman candle. Neither of them can look at the fireworks erupting right from his hand because they're too busy making eyes at each other:

His palm is warm and soft. A purple fireball erupts from his candle, but I only see it in my peripheral vision, because we're face-to-face now. His eyes are the warmest shade of brown I've ever seen. His teeth are a bright white flash as he smiles at me.

Edie's ignoring of the literal fireworks in favor of the emotional variety is such a vivid and beautiful image. And that image, of staring at the truth despite the distractions that life offers at every turn, repeats throughout the book. It's also a perfect metaphor for childhood: we often can't see the truth we most need, even when it's right in front of us, until we're ready to see it. With each revelation of the truth, we get a little bit closer to an answer for the eternal question of who we are.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound