Where the rubber meets the road

We need to talk about travel books in the 21st century.

Most people my age probably have fond memories of taking travel books on vacation with them. I still recall the bricklike heft and shape of the Let's Go USA guide that I carried on a long road trip across the southern US and up the west coast to arrive in Seattle. Of course, there were some problems with the publishing model of travel books; in the years between updated editions of certain guides, businesses would close, new forms of transit would start up, and prices would change. By the end of a travel book's life cycle it would become a kind of unreliable narrator, promising accuracy but delivering a kind of nostalgia-soaked snapshot of the recent past.

In recent years, when I've traveled, I've simply relied on my phone for information about my immediate area. And in many ways, the internet is a better travel guide than those fusty old print versions. The information is generally up-to-date, it's keyed in to the user's interests in the way a general-interest travel guide never can be, and it's basically a bottomless well of a resource.

But traveling while using the internet as a guidebook has its own serious flaws, too. Google search has gotten worse over the last five years, to the point where many of the top pages of search results are litanies of useless garbage. There's no sense of who to trust — pages might be rigged by paid content, for example. And no random search result is ever going to carry the authority and expertise of a well-researched guidebook.

Authorial intent is everything. But clearly, travel books have to do something to move forward into the 21st century, to justify their continuing existence.

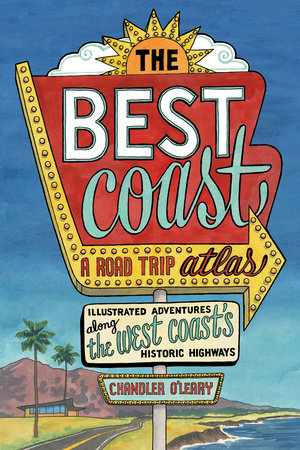

Tacoma author Chandler O'Leary's new book from Seattle publisher Sasquatch, The Best Coast: Illustrated Adventures Along the West Coast's Historic Highways, offers one possible path forward — a way to make travel books relevant again.

The indispensable trick here is O'Leary's artwork. Every page of this west coast road-trip itinerary includes O'Leary's full-color illustrations of roadside attractions and noteworthy architecture and scenic vistas and downtown maps. The book documents a couple of possible road trips from the Mexican border up to Canada along the west coast, and O'Leary's illustrations immediately convince the reader of her authorial integrity: she's obviously been to these places, or at least spent a lot of time researching the statues and ruins and wildlife that makes each stop along the way a special destination.

O'Leary's illustrations give the book a feel of a diary, or a letter mailed from one friend to another. It's the kind of intimacy that you can't get by Googling a location — a personal impression, a human adventure, a sense that she was there and she wants you to know what to expect and what to enjoy.

One of my favorite pages in Best Coast is O'Leary's account of Steinbeck's Cannery Row. Each page includes typeset prose conveyed in casual-reader-friendly blurbs, in the manner of old travel guides, and this page is no different:

Cannery Row, the waterfront strip originally known only as Ocean View Boulevard, served as the industrial heart of Monterey. It was dominated by commercial canneries that packed sardines into tins as an inexpensive seafood product. Monterey Bay had seemed like a teeming, inexhaustible resource — until overfishing decimated the sardines, and the industry collapsed in the 1950s. Today Cannery Row, restored and officially renamed for Steinbeck's novel, preserves many of the original buildings as a number of pedestrian-friendly shops and restaurants.

That's perfectly serviceable text that wouldn't be out of place in an old Fodor's or Lonely Planet guidebook, but the thing that really elevates the entry is O'Leary's drawings on the page. She draws a number of labels from old sardine tins — a mermaid posing on a green label, a sardine flying to the moon on another, a California seascape on a third — to illustrate the storied past of the place, and she draws a beautiful red cannery building along the top of a page to show how vibrant the area used to be.

These create emotions in a reader that no old-school travel book could summon — they illuminate the text in a way that a typical travel photograph never could, giving the reader a feeling of being right there, standing next to O'Leary, soaking it all in. Each of these illustrations feels like a friend pointing out a location of interest from the passenger seat: the beautiful architectural weirdness of Fresno; the awkward stance of a caveman statue in The Rogue River Valley; the fairy-tale weirdness of Bob's Java Jive, a teapot-shaped bar on South Tacoma Way.

This is a book I'd love to take in the car with me as I navigated the west coast from south to north, the kind of personalized compass that would point me in the direction of adventures, and it identifies a more intimate solution for travel books in an Extremely Online age.

I do wish that O'Leary had changed up the formula a bit. Most of these pages follow the exact same pattern: a two-page spread with art drawn all around the edges of the pages, with a series of typeset paragraphs in the middle. Had O'Leary made each page a little more visually arresting, the book would be more surprising, perhaps taking on the addictive feeling of discovery that a good road trip provides. I wish that O'Leary would have told a few stories in comic form, or provided a few full-page illustrations to break up the monotony of the page design.

But what's any American road trip with a little bit of monotony? Just as travelers are hypnotized by the sameness of highways, so too are readers hypnotized by the rhythms of Best Coast. That makes the jarring moments, the ones in which O'Leary does a particularly great job of capturing the grandeur of a redwood forest, say, all the more powerful. In the end, it's not the journey or the destination that matters most — it's who you travel with along the way.

Paul is a co-founder of The Seattle Review of Books. He has written for The Progressive, Newsweek, Re/Code, the Utne Reader, the Los Angeles Times, the Seattle Times, the New York Observer, and many North American alternative weeklies. Paul has worked in the book business for two decades, starting as a bookseller (originally at Borders Books and Music, then at Boston’s grand old Brattle Bookshop and Seattle’s own Elliott Bay Book Company) and then becoming a literary critic. Formerly the books editor for the Stranger, Paul is now a fellow at Civic Ventures, a public policy incubator based out of Seattle.

Follow Paul Constant on Twitter: @paulconstant

Other recent reviews

Talk about the weather

-

Interpretative Guide to Western-Northwest Weather Forecasts

March 27, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy on IndieBound

The man show

-

The Sexiest Man Alive

October 01, 2018

72 pages

Provided by publisherBuy online

Accidentally honest

-

The Shame of Losing

October 01, 2018

264 pages

Provided by authorBuy on IndieBound