Archives of Event of the Week

Literary Event of the Week: Sleeping on Jupiter at Elliott Bay Book Company

And so here we are, at the beginning of a shiny new fall. Fall is to the literary world what summer is to movie season: the season when the big names come out to play, when the big advertising budgets and media blitzes roll out. And every season, the books are accompanied with a certain amount of buzz—book chat, both positive and negative, from agents, librarians, and other literary folks with early access to review copies.

Sometimes, these books are instant classics, the kind of reading experience that engages even people who don’t pay that much attention to books. But as with summer blockbusters, sometimes that hype amounts to not much at all. Duds collide with runaway bestsellers, famous authors sometimes fail to impress their beloved fans, and new writers appear from (seemingly) nowhere to become household names.

This year, we’ve got new books from Zadie Smith, Michael Chabon, Maria Semple, Jonathan Safran Foer, Bruce Springsteen, and many more on the way. Thanks to Oprah’s pre-publication endorsement, we’ve already seen Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad become one of 2016’s rare must-reads. (Speaking of which: Hugo House is bringing Whitehead to Seattle Public Library on September 17th. Save that date.) It’s all almost too exhausting to think about.

Jupiter begins with our protagonist, Nomi, witnessing her father’s murder:

When the pigs were slaughtered for their meat they shrieked with a sound that made my teeth fall off and this was the sound I heard soon after my mother cut the grapefruit, and the men came in with axes…In my sleep I hear the sound of pigs at slaughter, the sound my father made.

Nomi is adopted and moves to Norway; she comes back to India a grown woman with a project in mind. The book addresses sexism and homophobia and masculine violence in a new way; it’s a novel that pushes at its culture as a force of modernity.

Jupiter has already been nominated for a Man Booker Prize and it’s won and been shortlisted for a bunch of other huge literary awards. And if you think that awards don’t mean anything—you’re only partly right, by the way, but that’s an argument for another time—you should know that the book buzz on this one is off the charts. Local booksellers can’t stop gushing over Roy’s latest, and booksellers are rarely wrong. Jupiter is that rarest of novels: a fiction that serves as an agent of social change. That’s hype you can believe in.

Literary Event of the Week: Nevertold Casket Company Reading #1

The Nevertold Casket Co. looks kind of like the cursed junk shop from Gremlins—a store that proudly carries “haunted” merchandise which could add a conversation piece to your living room or rain down eternal torment on your household in the form of a vicious spirit of vengeance from feudal Japan. It is a shop, in other words, that is full of stories. The wax dummy of a baby covered in syphilis sores has to have an explanation behind it, right? And why the hell would someone mummify a baboon? Well, thereby hangs a tale, and that tale is part of what you’re buying at Nevertold.

Founded by casket-maker Jackson Andrew Bennett, Nevertold is the sort of shop you run into once while wandering around the twistiest cobblestone streets in Boston, or the most ancient-looking neighborhoods in Manhattan, and then can never find again. The fact that it exists on Capitol Hill’s relatively mundane 13th Avenue is in itself some kind of a modern Seattle miracle. With its artful jewelry and antique taxidermy, it’s a store full of appreciation for aesthetics long since past, stuck in the middle of a part of town that is currently suffering from aesthetic amnesia.

And now Bennett, himself an author working on a book about grave-robbing, is launching what looks to be the first in a series of readings based out of the Nevertold Casket Co. It’s a pairing that makes sense — what’s an ancient curse, after all, without a few books and incantations around to add an eldritch air?

For a store that wraps itself so thoroughly in the past, the first Nevertold reading is a surprisingly current affair. Readers include Jenny Zhang, the Brooklyn-based poet and short story author who headlined the most recent APRIL Festival; local poetry dynamo Sarah Galvin; monologist and weed culture expert David Schmader; Sonya Vatomsky, whose debut poetry collection is titled Salt Is For Curing; and James Gendron, whose book title Sexual Boat (Sex Boats) tells you just about everything you need to know.

This is a strong lineup of local and local-friendly writing talent — seriously, if Zhang reads here one more time this year, we’re going to get to claim her as a part-time Seattle author — that should suitably christen a new reading venue in the Seattle firmament. With all due respect to the many bookstores and libraries that host readings all the time, occasionally pulling events into a nontraditional reading venue keeps the readings format fresh and surprising. If all that isn’t enough to attract your attention, event organizers also promise a cask of “haunted beer” from Outlander Brewery to keep things nice and spiritual.

Halloween, by any calendar’s reckoning, is two page-turns away. And it’s highly unlikely that all the readers at this event are going to thematically obsess on the macabre. But the unhinged hilarity of a Galvin reading can’t help but take on a new meaning when contextualized by sterling silver crow’s feet charms and funeral chairs from the 1900s. What’s a celebration of life without a little death mixed in at the fringes to keep things interesting?

Nevertold Casket Company, 509 13th Ave., http://nevertoldcasket.com. Free. 21+. 8 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: Wong/Akbar/Peñaloza/Lewis

As you know, we at the Seattle Review of Books publish a poem by a Seattle poet every Tuesday at 10 am. We always ask the featured poet to then choose the poet who we’ll feature on the next Tuesday. It’s a chain of Seattle poetry, made up of friends, fans, and acquaintences who’ve shared some laughs on the open-mic circuit. When I asked Seattle literary demigod Sherman Alexie to kick off our spring/summer 2016 poetry chain, I was intensely curious to see who he’d choose as the poet to succeed him. Out of all the poets in Seattle, who would Alexie spotlight?

Alexie’s decision was fast and decisive: Jane Wong. It was perhaps a surprising choice, if you expected Alexie to prop up some sort of a Literary Old Boy’s Network. Wong has been reading around town for a while now and she’s been collected in outlets like (the Alexie-edited) Best American Poetry 2015 and the Best New Poets 2012, but she doesn’t have many books to her name yet — just three chapbooks and a debut collection, Overpour, coming out from Action Books this coming fall.

But read Wong’s poetry and you’ll see why so many writers in town advocate for her. Consider “Apology in the Age of Construction,” the poem she published with us after being selected by Alexie. It opens with an incredibly striking image:

We can only recall the freak accidents:

the lightning bolt hitting the right arm

at a right angle, the bees pouring

from an overturned truck, the crocodile

that escaped on a lawn, sipping lemonade.

Those disasters are so unique, so particular, that each one could be its own short story. (At least the bee-filled truck is based on a real-life incident — a 2015 accident in which an overturned truck dumped 14 million bees on I-5. ““Everybody’s been stung,” a state trooper told the Seattle Times at the time.) You can see the cool yellow of the lemonade against the foggy emerald of the crocodile’s skin, the person spinning (to the right, and to the right again) after being struck by lightning.

But Wong expands outward from there to the Seattle outside our windows right now, casting her eyes on the intentional destruction that comes before construction. (“We laid down layers/of asphalt in the tradition of weavers.”) She looks at the skyline full of cranes and sees, simultaneously, a slow-motion accident and an unfolding possibility and a bizarre kind of playground:

In the early morning, we mistook snow

for falling specks of paint, a construction

site for an amusement park.

Look at a construction site without context and you see what looks like a combat zone. Look at a new building and you see a blank canvas. Look at a disaster the right way and you can find unexpected beauty. Tilt your head just right and you can hear Sherman Alexie laughing with surprise and delight at the way Wong cheerfully turned everything on its ear.

This Saturday at Elliott Bay Book Company, Wong is headlining a reading with two poets from Tallahassee — Kaveh Akbar and Paige Lewis — and Seattle poet Michelle Peñaloza. It’s a can’t-miss affair.

Literary Event of the Week: Cody Walker and friends at Elliott Bay Book Company

Before Cody Walker left Seattle to teach English in Ann Arbor, he was frequently described as a quintessential Seattle poet. Go to any open mic night and you’ll likely find some poet who doesn’t even realize he’s aping Walker’s schtick—an endearing blend of earnest and funny, formally inventive and respectful of tradition. For a time, Walker was a ringleader of the poetry scene, a funny and fun poet who was always willing to share the spotlight with up-and-coming Seattle writers. But even poets have to eat, and this city isn’t exactly throbbing with opportunity for those who want to teach poetry.

Walker doesn’t live in Seattle anymore, but Seattle is still on his mind; in 2013, he co-edited an anthology titled Alive at the Center: Contemporary Poems of the Pacific Northwest. And his newly published second collection of poems, The Self-Styled No-Child, is packed with the kind of poems that won him adoring crowds at the Hugo House and other venues around town on a regular basis.

Comedy and sincerity live side-by-side in Walker’s poems, and no poem in No-Child is so perfect an example of this as “A Skeleton Walks Into a Bar,” a poem named after one of the hoariest jokes of all time—“a skeleton walks into a bar, says ‘gimme a beer and a mop’”—that expands into a meditation on death. And then at the end, Walker throws his hands up in the air and surrenders:

and—fuck it, it’s just a joke. Meanwhile, move closer, Love, now that we’re both awake.

Is there a trick more noble in all of poetry than the desperate last-stanza turn from impending death to booty call? If it was good enough for Keats, it’s good enough for Walker.

On Monday the 15th, Walker will read at Elliott Bay Book Company to celebrate the release of No-Child. In typical Walker fashion, he’s sharing the spotlight with Seattle-area poets including Rebecca Hoogs, Rachel Kessler, Julie Larios, Sierra Nelson, and Jason Whitmarsh. It’s a quintessentially 2000s-era-Seattle lineup (only Ed Skoog, who himself moved to Portland not so long ago, is missing.) Sure, it’s a different city now. And sure, the face of Seattle poetry is changing — and many would argue it’s changing for the better. But listen: just because Cody Walker left Seattle doesn’t mean that Seattle left Cody Walker. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

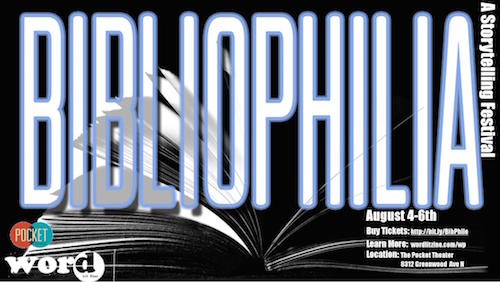

Literary Event of the Week: Bibliophila Storytelling Festival at The Pocket Theater

Bibliophilia is made up of five events taking place on August 4th, 5th, and 6th at the Pocket Theater in Greenwood. The idea is to bring a sense of drama and performance to literature. “I’ve been to a lot of readings,” Phillips explains, “and there are folks who are wonderful writers but not great readers. It’s not that the author doesn’t have talent, but they’re not a reader by nature.” With her improv and circus training, Phillips decided she was uniquely qualified to bring “the page to the stage” in new and interesting ways.

The festival opens and closes with a unique event format, titled “Chapter One.” An author reads the first chapter of their book, and then an improv troupe reenacts the story from memory. Aside from the usual thrill of watching someone work up a performance from scratch, the audience will be keyed in to catch the differences between the text and the impromptu mini-play. Thursday night’s Chapter One reader is Raven Oak, who’ll be reading from her sci-fi novella Class-M, about a space tourist who bumbles into a military thriller. Saturday night brings G. G. Silverman, author of Vegan Teenage Zombie Huntress. The format of the performance is a clever conceit that plays with our natural human impulse to nitpick the differences between a book and its adaptation. “I think there’s a lot of joy in that,” Phillips says, and there’s plenty of opportunity for surprise if the actors go “off-book.”

Friday night’s programming opens with “That Moment,” featuring an array of Word Lit Zine authors, who will read poems. Improv performers will then speculate on and enact their idea of the moment of inspiration for the poem. The actors might imagine that a sad poem springs from the night a poet realized they were getting divorced, for example, and incorporate pieces of the poem into the couple’s argument. Phillips calls it “an examination of how art imitates life, which imitates art.” The second Friday night show is titled “Through (rose) Colored Glasses,” in which women of color explore their heritage and lineage through poetry. This is the event that features the highest-profile Seattle-area readers, including Sasha LaPointe, Yolanda Suarez, Laura Da’, and Natasha Marin, who reads as Tashi Ko.

And in case you need a little bit of sexy to drag you out to a literary festival, Saturday night’s program opens with Naked Girls Reading which is, well, exactly what it sounds like: naked women—in this case, Jesse Belle-Jones and Sailor St. Claire—sitting onstage, reading stories to the audience. Phillips hopes with this festival to bring improv audiences out to their first literary event, and vice versa. She calls Bibliophilia “a festival for a lot of different people. Whether you’re a storytelling artist a poet, or a performer, you’re going to find this exciting because it’s a new kind of performance.”

Bibliophilia events are $10 advance/$14 at the door. Buy tickets and learn more at http://wordlitzine.com.

Literary Event of the Week: Donald Ray Pollock at Elliott Bay Book Company

You can pinpoint the origins of Donald Ray Pollock’s literary genius directly to a town in Ohio called Knockemstiff. Pollock was born and raised there, and he worked in a nearby paper mill for three decades. With a population just under 60,000, Knockemstiff is the kind of town that you don’t typically find in contemporary American literary fiction; half-rotten by meth, starved for hope, and entirely broke, it’s about as far away from the world presented in Jonathan Franzen’s novels as you can imagine.

Pollock titled his first collection of stories Knockemstiff, and except for a piece of one story titled “Honolulu,” the entirety of the book takes place in the Ohio town of the title. The characters are blue collar, prone to eating bologna, given to occasional fits of violence. It was one of the best debuts of the first decade of the 21st century. His first novel, The Devil All the Time, is about a serial killer in Knockemstiff. And his newest novel, The Heavenly Table, tells the story of a family feud set in the early days of the 20th century.

All of Pollock’s interests are on display in Table: the effect of technology on work, the rippling impact of violence, the desperate decisions that lead to crimes, and the difference between the America of our dreams and the real America of the heartland. If this sounds way too serious, I’m failing at my job, because Pollock’s sense of humor is dark and broad; characters in this book are obsessed with a pulp fiction hero named Bloody Bill Bucket.

When Knockemstiff debuted, Pollock faced a lot of comparisons with Sherwood Anderson’s classic novel Winesburg, Ohio. It’s easy to see why those connections were made: big casts of interconnected characters, small-town America, Ohio. And Pollock himself seemed (rightfully) flattered by the comparison.

But if Pollock is a modern-day Anderson, it’s by way of authors like Harry Crews, Chuck Palahniuk, or the Bret Easton Ellis of American Psycho. While Pollock doesn’t revel in violence for entertainment’s sake, he’s not afraid to painstakingly lay out a gruesome scene in order to make a point. America’s heart has a hole in it, and the blood is getting absolutely everywhere.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. Monday, July 25th at 7 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: REMEMBER ME

Here’s a poem called “Red Lineage:”

My name is Vulnerable Red.

My mother's name is Staunch Red.

My father's name is Red-Eye Red.

I come from a people known for flagrance

& survival.

Remember me.

Here is another poem called “Red Lineage:”

“Red Lineage” is a poem told in variations, and written by many poets. In some of the poems, the mother’s name is Sea Red or Bad to the Bone Red and the father’s name is Mountain Red or Murder Red. In some, the people are known for “originality and truth” or “starting fires and depravity.” They all want to be remembered.

In videos of “Red Lineage,” people usually stand in front of a red background, often in ornate costumes, and read their variations of the poems. They submit under anonymous names like “Jessica A.” or “TW.” At redlineage.com, people are encouraged to type their own “Red Lineage” poems into a form, with blank spaces just waiting to be filled in, Mad Libs-style. You can go and fill out as many as you like right now, if you want. “Red Lineage” was founded by Seattle poet Natasha Marin as a ritual/performance art piece. The project takes on many different aspects: sound collage, dance, video, all connecting themes of parenting and legacy and the color red.

By using a simple poem that can withstand infinite variations as the container for the project, Marin is allowing an unending parade of agendas and ideologies and beliefs to funnel through “Red Lineage.” The many intents mean the poem is always changing, but something ineffable survives every modification, no matter what a particular poet brings to the framework. You’ll find echoes, strings connecting poems, a thematic influence that seems to run deeper than words or even thoughts: perhaps the meaning springs from somewhere inside our blood?

This Thursday, Marin presents “Red Lineage” as part of a show called REMEMBER ME at Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar on Capitol Hill. She’ll be digging deep into a multimedia archive collected over a decade. That’s a lot of contributors — and a lot of mothers, and fathers, and memories. From her women-only Read and Bleed series to her Miko Kuro’s Midnight Tea events to her People of Color Salons, Marin’s work is all about community and inclusion — in a city whose art scene erases people of color with alarming regularity, she empowers and uplifts people of color, women of color, artists with disabilities, and other neglected populations. In some ways, REMEMBER ME feels like the purest extension of Marin’s work. She’s sharing a common tongue with people, inviting them to speak for themselves, and demanding that everyone notice, and, yes, remember them.

Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, vermillionseattle.com. Free. All ages. 6 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: N.K. Jemisin at the Seattle Public Library

N.K. Jemisin’s 2014 short story “Walking Awake” begins with a very familiar power dynamic. In the opening lines a “Master” appears, “wearing a relatively young body.” The Master appraises some young, strong bodies, which we’re told will then be sent to the “transfer center.” It’s pretty clear within a few paragraphs that “Walking Awake” is a science-fiction take on the master/slave dynamic. Readers almost immediately get the sense that Masters subsume slave bodies entirely and live inside them, a surprising elaboration on the idea that anyone can “own” another human being’s body.

But Jemisin isn’t interested in a polite, finely wrought allegory. Soon we meet a Master’s potential body: “Ten-36 was a bright, pretty child, long-limbed and graceful, Indo-Asian phenotype with a solid breeding history.” Support staff assures Ten-36 that “The Masters were always kind. Ten-36 would spend the rest of her life in the tall glass spires of the Masters’ city, immersed in miracles and thinking unfathomable thoughts that human minds were too simple to manage alone. And she would get to dance all the time.” Like most fairy tales, it’s a lie. Ten-36 rests on one of two tables and prepares herself for the procedure.

When the Master came in and lay down on the right-hand table, Ten-36 fell silent in awe. She remained silent…when the Master tore its way out of the old body’s neck and stood atop the twitching flesh, head-tendrils and proboscides and spinal stinger steaming faintly in the cool air of the chamber. Then it crossed from one outstretched arm to the other and began inserting itself into Ten-36.

The image that Jemisin was coaxing the reader into imagining, that of two people lying on individual steel tables as headbands transfer thought waves from one body into another, was a feint for a more horrible truth, a transaction of spilled blood and torn flesh and broken bone. The reality of slavery, the horror of one body forcing its will on another, is always worse than whatever your imagination can muster.

Jemisin has written novels and short stories and even a novel adaptation of the Mass Effect video game. Her fiction is interested in the idea of freedom and free will, of oppression and struggle, and of trying to explain the inexplicable. It’s big-idea sci-fi, the kind of mind-exploding fiction that is not at all interested in showing you something you’ve seen before.

Seattle-area sci-fi writing organization Clarion West is bringing Jemisin to town as the fourth reader in their summer reading series, with a musical set by SassyBlack. If you believe that good sci-fi holds a mirror up to our time, this is the must-see Clarion West event of the year. Everything Jemisin writes about is tied to Black Lives Matter and Donald Trump’s nationalist racism and the legacy of violence that white people still enact on African-American bodies today. These are stories that tell the truth with such passion that you cannot avert your eyes for even a second.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, spl.org. Free. All ages. 6 pm.

Literary Event of the Week: How to tell a story using this one weird trick

UPDATE: Due to illness, the event celebrating author Dorthe Nors that was originally scheduled for this week has been canceled.

Headlines used to be an art form. Newspapers once hired people specifically to condense all the drama and nuance and vitality of a news story into five or six words that could grab readers at twenty paces.

Now the headline has become the domain of the social media expert, and their goals are much more modest: to divert you, however momentarily, from your Facebook news feed. Which is why every headline feels like a sleazy pick-up line: without that relentless clash between specificity and withheld information — This Weird Trick Might Make Your Life Actually Worth Living — or sheer factoid overload — 57 Rock and Roll Shows That You Have to Attend This Week, or Else Something Terrible Will Happen to You — a headline is never going to divert you from the soap opera that is your friends’ lives.

Minna sees the mothers’ group often.

The mothers’ group takes walks in Amager.

The mothers’ group drives in formation.

The mothers’ group is scared of getting fat.

The mothers’ group goes jogging with their baby buggies.

The mother’s group eats cake at the café.

The mothers’ group contends gently for the view.

The baby buggies pad the façade.

The baby buggies form a breastwork.

Minna fears the mothers’ group.

Minna cannot say that out loud.

Minna has no child.

This format can be a bit much. The uniform brevity of the lines makes the story’s staccato pace uncomfortably relentless. The other novella in Winter, titled “Days,” is the perfect antidote for readers exhausted by headline overdose. It’s a series of lists written by a woman on the verge of cracking up. Unlike the short bursts of Minna’s story, the lists in “Days” have variegated rhythms and cadences:

2. Had my last wisdom tooth extracted.

3. Had my mouth stitched up with needle and thread by a man who said I would heal slowly because my age was against me.

4. as if I didn’t know that, I thought, as if it isn’t such things that make me stop midmotion in plotting out the future, and if you’ve got something for aching of the heart, Dr. Lars, if you’ve got something for emptiness and loss of voice, if you’ve got something for time’s tooth, then be sure to add it to my bill, but otherwise I think you should hold your tongue, unless you want to hear my philosophy of teeth — would you like to hear it? Would you?

5. Didn’t get the tooth to bring home.

Though they make up the traffic of our online lives, lists and headlines have never felt so alive, so uncomfortable, so raw as they do when Nors writes them.

Literary Events of the Week: Koon Woon and Margin Shift

Sometimes all the good things happen in a single night. These are the nights where you want to throw yourself into a large sterile glass tube, flip a mad-scientist switch, and then send a clone or two staggering off into the night, just so you’re sure you don’t miss a thing. Thursday, June 23rd is one of those nights.

The poetry collective Margin Shift has for years been presenting some of the liveliest, most diverse readings in town. Every one of their events is, well, an event. But on the 23rd, they’re hosting an outdoor “Almost Solstice”-themed barbecue/reading that looks like it could be one of the more fun, laid-back poetry events of the year.

The lineup includes a mix of Seattle poets (Sarah Baker, Tracy Gregory,) Seattle poets who are moving to Buffalo, of all places, (Travis A Sharp,) and poets from the Midwest (Laura Burgher) and Colorado (Denise Jarrott.) They’re young and vivacious authors, reading outdoors on one of the longest days of the year. Throw in a little beer and barbecued meat and exposed skin and this is a reading that could get you laid.

Koon has lived through enough to pack a thousand memoirs. He has publicly struggled with mental illness and he has lived on the streets of Seattle. He has worked dozens of odd jobs, become a small-press publisher, and written books sporadically throughout his life. (He published his second book, Water Chasing Water, at age 64.) Koon is a foundational force in Seattle’s literary scene, and he has not received the mainstream recognition that he deserves. This memoir, and this reading, are hopefully the beginning of the end of obscurity for him.

“I entered the literary world through the back door, writing to channel my emotions instead of acting out in the streets,” Koon wrote for Poets & Writers magazine in 2013. “I wrote because I could assuage my mental illness by clarifying to myself my feelings and perceptions of reality.”

Press materials for this reading refer to Koon’s “consensual” relationship with reality, and that’s perhaps the best description of a poet that I can imagine: Woon’s work is visceral—he writes about flesh and blood and bone and work—but it is not quite realism. In fact, his writing always feels like it’s coming from a different plane, and that he’s visiting us here on this godforsaken mudball because he likes us and wants to spend time with us. But he doesn’t need to be here: he’s one of those rare talents whose presence feels like a gift: surprising, spontaneous, overwhelming.

Margin Shift: 1809 E John St. 7 p.m. All ages. Free. Paper-son Poet: Couth Buzzard Books, 8310 Greenwood Ave N., http://buonobuzzard.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Literary Event of the Week: Happy Family with Maria Semple

“The pregnant girl enters the Trenton Family Clinic,” begins Tracy Barone’s debut novel Happy Family, “looking like she parted the Red Sea to get there. The lower half of her dress is wet with amniotic fluid, and the upper half is streaked with sweat.” This is a grand opening line for a novel, dense with imagery, evocative of the Bible, and thick with bodily fluids. It promises both legend and messy corporeality. It’s a woman’s body, split in two.

Happy Family is the story of Cheri Matzner, the baby who’s straining to be born in the book’s first sentence. Her mother, a teenager, runs away as soon as she gives birth, and Cheri is soon adopted by a couple with their own sketchy past. The book picks up with Cheri as an adult (seemingly of the high-functioning variety) as the secrets from her past boomerang back in the general direction of her head. On Thursday, June 16th, Barone will be reading from Happy Family at the Central Branch of the Seattle Public Library downtown. The most important element of this reading for Seattle audiences is that she’ll be joined onstage by Seattle author Maria Semple, who will be interviewing Barone about her novel.

It’s the appearance from Semple that elevates this from an intriguing appearance by a first-time out-of-town author into an absolute must-see. Semple, a writer for TV shows like Arrested Development who moved to Seattle and found international fame with her second novel, Where’d You Go, Bernadette, is an avid reader. If she loves a novel, she’ll recommend it to anyone within hollering distance. If she hates a book—and she hates a lot of books—it’s almost as though she’s morally offended. Her appearance at Barone’s reading is a sign of approval from a famously opinionated writer.

In addition, this is a rare public appearance for Semple; she’s been holed up for over a year writing her follow-up to Bernadette, a new novel titled Today Will Be Different which will be published this October. It’s possible that, since she’s been immersed in the new book for months, she might accidentally share some information about Different, which so far has been relatively shrouded in mystery, at this reading.

These two writers should have a lot to discuss. Barone could learn from Semple’s wild ride to international literary stardom. They could compare the way they use humor to soften the impact of some of the sharp-edged drama in their books. (Barone will use an off-kilter observation like a character’s propensity to talk dirty in Italian when aroused to mask a dysfunctional relationship, for instance, and Semple used Bernadette’s pathological loathing of all things Seattle to disguise her inner turmoil.) Wherever the conversation takes them, you’ll want to follow.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Event of the Week: Graphic Masters opening night at SAM

If you grew up as a comics fan before the turn of the century, the giant posters in front of SAM celebrating their new Graphic Masters exhibit right now are sure to send a little shiver of joy running down your spine. Walk down First Avenue and you’ll be sure to see them: two giant posters reproducing artwork from Goya and Picasso, right next to a giant poster featuring Robert Crumb.

One of the central exhibits in Graphic Masters are the over 200 illustrations that Crumb made for his faithful interpretation of the Book of Genesis. Make no mistake, these aren’t etchings or sketches—they’re comics. More than that, they’re Crumb comics, featuring a big-legged Eve who has never before looked quite so stacked as she wanders, buck naked, around the Garden of Eden. Though some — myself included — would argue that the Genesis adaptation is not Crumb’s most brilliant work, it is most certainly stunning. And anyone who attended the Frye’s Crumb exhibit a few years ago can tell you that in person, his work looks almost holy: the individual feathered lines are pressed into the page, a reminder that a human hand created these almost-impossibly beautiful cartoons.

By now the embrace of Crumb feels almost commonplace, but in the 1990s, it was impossible to think that a major museum would be celebrating a cartoonist on the same level as canonical masters like Rembrandt and Hogarth. And this isn’t SAM slipping Crumb into an exhibit by giving him a pass as an honorary fine artiste—in fact, SAM is jumping completely into the comics world by celebrating the fabulous comics scene that has sprung up in Seattle over the last few years.

The opening night party for Graphic Masters features a special limited-edition paper called Whims, in which cartoonists who have contributed to Seattle’s scene-making Intruder comics anthology interpret works by Goya. And it’s asked the organizers of the annual Short Run Comix & Arts festival to put together a special zine and print fair at SAM. Short Run organizer Kelly Froh can’t quite believe this is happening; she says getting a call from SAM “was a big deal for us, to be acknowledged in this way, and we were happy to do it.“

She’s right to call it a big deal. Though legitimacy no longer escapes comics, there’s something different going on here. The literary world has embraced comics for almost twenty years now, but the fine art world, at least in Seattle, has never quite come out to celebrate comics quite like this; it’s a big moment in which a huge institution opens its doors to Seattle artists who have toiled for decades without even a hope of SAM’s acknowledgement. Local comics artists including Colleen Frakes, David Lasky, Aaron & Jessixa Bagley, Mita Mahato, and Megan Kelso will have tables of books for sale at the show, and Fantagraphics Books will be represented by Jim Woodring, who will be performing tricks with his enormous pen. (This is not a euphemism.)

This is a big night for Seattle comics, a celebration of a scene that has quietly been amassing momentum over the last handful of years. An acknowledgement by an institution as large and respected by SAM was not necessary for the scene—our cartoonists by and large already know they’re part of something great—but the endorsement isn’t meaningless, either. There’s something more happening in Seattle’s cartooning community than, as Crumb self-deprecatingly put it many decades ago, “only lines on paper.”

Seattle Art Museum, 1300 1st Ave, 654-3100, http://seattleartmuseum.com. Free. All ages. 5 pm.

Event of the Week: Contagious Exchanges at Hugo House

There used to be two LGBT-themed bookstores on Capitol Hill alone. Now there are none. Lots of people would say that this is a sign of progress — after all, though we may not have a Beyond the Closet or a Bailey/Coy on Capitol Hill anymore, pretty much every bookstore in town now has a huge section devoted to LGBT issues. Virtually every bookstore I can think of has at least one LGBT employee, and some have many more than one. With the mainstreaming of gay culture, many would argue, why would you need a space specifically for LGBT literature?

Well, uh, because it’s important. Because books are how we learn, and because LGBT youth will feel more comfortable if they can visit a space away from the judgmental eyes of cisgender browsers where they can feel included as they learn about themselves. Because no matter what your age, sometimes it’s worthwhile to make a space where you can breathe and be yourself. Because it’s important to have a place dedicated to community and conversation.

If you’re out at a literary event and you see Seattle author Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore there, you know you’ve made the right choice for the evening. Her taste is impeccable, and her politics are righteous. Now she’s finally launching a new reading series to create a much-needed space to discuss queer matters. In October, Bernstein Sycamore’s new Contagious Exchanges series will kick off at the Hugo House. It’s billed as “a monthly series featuring two dynamic writers bridging genre, style, sensibility, and all the markers of identity in queer lives.”

But on Thursday June 2nd, Bernstein Sycamore is hosting a pilot episode for Contagious Exchanges, a proof-of-concept to give audiences a Pride month preview of what to expect this fall. The first two people who’ll be joining Bernstein Sycamore in conversation are poets Tara Hardy and Anastacia Tolbert. Hardy is a self-described “working-class queer femme poet” who has served the community broadly (she was Seattle’s Poet Populist) and the LGBT community more specifically (she has read and performed with queer reading groups for her entire career). Tolbert is the Hugo House’s current writer-in-residence, and she is seemingly everywhere right now, speaking out at events for people of color and queer writers. These two poets sharing one stage should be incendiary; putting them together with a curious firebrand like Bernstein Sycamore might just result in an explosion.

But more than just a promising reading series, what Bernstein Sycamore is doing with Contagious Exchanges is claiming a space to discuss queer issues in literature. She’s taking back some of the public conversation and claiming it in the name of her cause. When the LGBT bookstores shut down, some assumed it was because the community wasn’t there to support it. Bernstein Sycamore is out to prove them wrong; Contagious Exchanges is proof that there’s more to be said, and written, and discussed about the state of queer writing in America in 2016. Make sure you’re there to listen, and to add to the conversation.

Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Event of the Week: Lindy West reading from Shrill at Town Hall tonight

Tonight, Lindy West reads from her memoir Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman at Town Hall Seattle, and it’s kind of a triumphant homecoming after the first leg of what looks to be a long book tour: she’s debuted the book in Chicago and in Brooklyn but she hasn’t yet read to a hometown crowd.

When she sat down with me for an interview, I asked Lindy something I’ve been meaning to ask for a very long time: there was a point when she and i worked together at The Stranger when she was becoming a nationally famous feminist cultural critic. In the days before the internet, that would have been the exact point when a writer would have packed up, left Seattle, and moved to New York City, to try to land jobs at high-paying magazines. Did Lindy stay in Seattle because the technology allowed her to telecommute, or was there something else that was keeping her here?

“I just love Seattle so much,” Lindy replied, “and I always have. Both of my parents are from here. There’s something about knowing that when I drive through downtown, I can see my dad walking down the street with his briefcase in 1973.” She said she “had the good fortune to keep getting jobs where they said I could work from wherever, so there’s just no compelling reason to go.” That said, “I know that I’m missing out on things. It’s hard to know what my career would be like if I had moved to New York. I definitely miss out on things like,” and here she screwed up her face with a special kind of disdain, “media cool kid happy hour, or whatever.”

It’s hard to imagine a more famous version of Lindy West right now; her book is getting rave reviews everywhere and she’s doing interviews with seemingly every media outlet in the English-speaking world. But part of her appeal is that she can be the totally fearless, brash, hilarious warrior on the internet and in print, and then she can come home and be a Seattleite who loves her family and friends and city in a completely earnest, un-New-York-y way. It’s hard to imagine a Lindy West without Seattle’s influence, and it’s impossible to imagine a Seattle without Lindy West.

Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Event of the Week: Andi Zeisler and Amelia Bonow at Town Hall Seattle

In the 1990s, feminists drew lines between a pair of up-and-coming magazines: in many social circles, you could either be a fan of Bitch Magazine, or you could be into Bust. Bitch was uglier than Bust, less glossy. Bitch was interested in feminist theory and it reviled the concept of selling out; Bust was more fun, more inclusive. Bitch had way more words per page, and fewer celebrity interviews. Bust got a fancy book deal and great placement on Borders’ newsstands around the country; Bitch was often tucked in the back of the racks, with the philosophy magazines and some of the weirder subcultural signifiers like The Comics Journal.

If you had asked me to predict the future back then, I probably would have sworn that one of those magazines would be gone by 2016. Though as far as I can recall, the editors of Bitch never explicitly called out the editors of Bust or vice versa, the two seemed eternally at odds. Two magazines enter the feminist Thunderdome, and only one can leave. Right? Happily, no. Both Bust and Bitch are still around today. There’s room enough in the world, it seems, for two perspectives on feminism.

But even in 2016, you’ve just gotta pick a side. My feminist tastes always leaned more toward Bitch, because it was prickly and sarcastic and dedicated to its own unalloyed principles. I didn’t realize it back at the dawning of the Bitch/Bust days, but by siding with Bitch I was declaring my allegiance to Andi Zeisler, the cofounder of the magazine. Zeisler’s writing exemplified—and still exemplifies—Bitch at its best: she’s smart and funny and honest and more than a little condescending to her enemies. Zeisler wrote in the 20th anniversary issue of Bitch that she was somewhat disappointed to see that her magazine was still around: “when your mission is to respond to crappy, insulting representations of gender, race, and more, after all, the goal is to put yourself out of business.” But there will always be more idiots, and so we should be grateful that there are people like Zeisler who can call those idiots out.

On the Seattle stop of her book tour, Zeisler will be in an extended conversation with Seattle-area #shoutyourabortion founder Amelia Bonow. Whoever thought up this pairing deserves a raise; Bonow is loud and unapologetic and more than a decade younger than Zeisler, which means the two will have to navigate a slight generational gap in order to reconcile their views on feminism. This should be a hell of a talk: loud, angry, unapologetic, funny as hell.

Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Event of the Week: Epilogue/Prologue at Hugo House

Seattle is right now trapped in the nether realm between openly mourning the past (see editor Jaimee Garbacik’s Ghosts of Seattle Past project) and openly agitating for the future (see the conversation about how quickly we can get light rail up and running to Ballard.) Tonight, the Hugo House finds itself exactly in between those two polar Seattle extremes, as a kind of Schrödinger’s nonprofit writing center. In twelve days, the House moves to its temporary headquarters on First Hill as a two-year guest of the Frye Art Museum while the old structure is demolished to make way for a shiny new facility at the base of five stories’ worth of condos.

For one last glorious Saturday night, the House is hosting a party called Epilogue/Prologue, a free celebration of the center’s past and its future. It should be a breathtakingly sloppy evening; partiers will be encouraged to write messages on the walls of the House. Will they reminisce over some of the best readings the House has hosted, like the time both Sam Lipsyte and Ben Lerner read in a single enchanted evening, or when Maria Semple unveiled pieces of what would become Where’d You Go, Bernadette?, or when Stacey Levine read a creepy story about the ghosts of mothers haunting houses that glowed with "the sweetness of cabinetry, or maple syrup?" Will they finally write down the gossip that has previously only been whispered about certain disgraced former Hugo House staffers? Will they admit to nasty trysts in the ever-filthy Hugo House bathrooms? One would certainly hope so. The best graffiti will be preserved and displayed in the new Hugo House two years from now, so there’s a real opportunity for immortality here.

Epilogue/Prologue also features booze, a “past room” full of photos from the House’s (nearly) two decades of continuous operation, food trucks, a confession booth, and a poetical-scientific experiment from lyrical behaviorists the Vis-à-Vis Society. But sometimes the best party features are the unplanned ones: get enough writers and enough beer into a single structure, and there’s likely to be fireworks, or fucking, or tears, or all three. And if you ply House staffers with a few drinks, you might be able to convince them to sneak you down into the basement to investigate the (supposedly empty) child’s coffin hiding in a musty passageway. (The building used to be a funeral home.)

But before you start singing “Danny Boy” and whining about how new buildings are all “boxy” and “have no soul,” it’s important to remember a few things: first of all, the House might be temporarily moving to First Hill, but it’s not really going anywhere. Second of all, it’s not every day that a nonprofit writing center gets an opportunity to reimagine itself, so it’s obviously more constructive to try to shape the House that comes than fret about the House that was. (I’m still pulling for them to open a bar in the new space that’s open seven days a week and becomes its own kind of literary center.) And third of all, remember that nobody likes a writer who can only look backward. All good writing faces forward, and the only future that really matters is the one you write for yourself. Hugo House, 1634 11th Ave, 322-7030, hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Event of the Week: Independent Bookstore Day on Saturday, April 30

When the Mall del Norte branch of B. Dalton booksellers closed in January of 2010, CNN reported, the city of Laredo (population 250,000) became the largest American city without a bookstore. “The closest bookstore is now 150 miles away, in San Antonio, Texas,” wrote CNN’s Ed Lavandera. Laredo was likely just the first of many American bookstore deserts, as Barnes & Noble continues to falter with every quarterly earnings report and rural retail zones get sucked dry by Walmart and Amazon.

Seattle stands apart from the nation because we have a dense population of thriving independent bookstores, and on Saturday, April 30th, those bookstores are throwing a party to celebrate our unique bookstore culture. Seventeen local booksellers (including far-flung shops like Liberty Bay Books in Poulsbo, Edmonds Bookshop, and Island Books on Mercer Island) are observing Independent Bookstore Day with exclusive books, prize giveaways, and author appearances.

A complete list of events would be way too long for this space—check your local booksellers’ website for schedules—but highlights include a local sci-fi authors panel (featuring Greg Bear, Robin Hobb, Elliott Kay, and Matt Ruff) at University Book Store, free coffee and scones at Third Place Lake Forest Park, a release party for Underground Seattle featuring local cartoonists at Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery, all sorts of cooking demos all day long at the Book Larder, cake at Secret Garden Books, and novelist Stewart O’Nan at Elliott Bay Book Company. (And at 7 pm, I’ll be doing an onstage chat with American Book Award-winning author Shann Ray at Phinney Books.)

It’s impossible to imagine a Seattle without its array of independent bookstores catering to every audience, from the stalwart genre outposts like Seattle Mystery Bookshop in Pioneer Square, which just earned a new lease on life thanks to a successful crowdfunding campaign, to the STEM-obsessed Ada’s Technical Books on Capitol Hill. These bookstores are the reason why Seattle has such an atypically overstuffed literary calendar for an American city, with anywhere from 3 to 7 literary events happening every single weeknight, and they supply us with our national reputation as a home for hyper-literate book nerds.

Artistically and commercially, Seattle’s values are closely aligned with the values of independent booksellers. We revere books, we loathe censorship, and we absolutely hate it when someone tries to control the way we think. Maybe that’s why we’ve got the best damn bookstores in the country.