Archives of Exit Interview

Exit Interview: Seattle cartoonist Eroyn Franklin is leaving Short Run in good hands

Eroyn Franklin is consistently one of the most interesting cartoonists in Seattle. Anyone who has seen her 2010 comic Detained, which documents the living conditions in Washington's immigrant detention centers via a comic laid out in a single unbroken scroll of paper, knows that she's formally inventive and narratively interested in what it means to be a human in the world.

But Franklin has perhaps been best-known for the last few years as one of the cofounders and organizers of Seattle's amazing Short Run minicomics and arts festival. With fellow cofounder Kelly Froh, Franklin has always been right in the thick of the festival, greeting guests and solving problems as thousands of people buy and sell comics around her.

Last week, Franklin announced that after seven years she was retiring from her role as a Short Run organizer to focus on her comics work. This week, I met with Franklin at a coffeeshop to talk about the process of leaving Short Run, why she's confident in the organization's future, and what she's working on now. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

You can keep track of Franklin's work and appearances through her website.

Franklin photographed at the Short Run afterparty in 2017.

Could you talk about how you came to realize that you were ready to move on from Short Run, and what the process of leaving was like?

I had definitely been feeling for the past two years that it was getting really hard for me to manage the responsibility of Short Run — that it was getting so big, and more work was being added every year, but there wasn't necessarily much more compensation for that. So I was having to work a lot of different freelance jobs in order to make sure that I could be a part of this creative project. And it does feel like its own creative project.

But that meant that other areas of my life were kind of suffering. I wasn't making as many books as I wanted to make. I was always anxious and depressed and swinging back and forth pretty wildly. I knew that something had to change, and it took something like two years to realize that leaving Short Run was something that had to happen. I just had to leave in order to give myself the space to pay attention to the other aspects of my life that I had set aside.

I started talking about it in earnest last summer. [Short Run cofounder Kelly Froh and I] had conversations up until [last year's] Short Run that were like, 'I'm pretty sure that I'm going to leave. Kelly, whatever you want to do is perfectly fine. If this is too much for you to do on your own, we all understand. The community understands this is a big effort.'

But right after Short Run she was like, 'I can't not do this. It was so perfect this year — it ran so smoothly and it was so huge and everything was vibrant.' For me, it was a wonderful way to say goodbye because I could experience this peak of joy, but for her it really made it clear that she needed to continue on.

So we worked together to help her build a board that would sustain the vision that she had and that we had.

Do you think about what might have happened if Kelly wanted to quit, too?

Yeah, it would definitely break my heart if Short Run folded. But heartbreak is also a part of life. Kelly and I have always talked about how our friendship comes before anything else — that we are a team that runs this organization, but really it's our friendship that makes all that possible.

So I was looking out for her and she was looking out for me. She never made me feel guilty about leaving. She never tried to pressure me to stay. She understood it. And I know she is going through a lot of the same feelings that I have. We both have problems with anxiety and depression and it is overwhelming.

So yes, I would have been okay if she decided to shut it down, of course, because that would've been her decision for herself. But it's so great to have this legacy that I get to be a part of. And I am one of the cofounders of this great, magical experience.

So what's happened since then?

Immediately afterwards, I had one day where I felt free. I could imagine myself just walking into the studio and just writing an entire book. But in reality I hit a pretty deep depression for about three months, and I just felt like all of my identity was wrapped up in Short Run. It's my community. It's my friends. It's everything. And losing that, all of a sudden — the reality of it, and what that meant, really dragged me down.

And then I walked into the studio to work on this book that was actually supposed to be a collaboration with my ex. And it turns out it's really hard to write when you're just crying all day. So it took me awhile to set that aside.

I went to an artist residency at Caldera Arts, which is in central Oregon, and so I got to spend a month in an A-frame cabin and my only obligations were to make art, walk around, and do whatever I wanted. It was so freeing. [Before Caldera,] I was so depressed that I thought I was going to give up on art, give up on writing, give up on comics, and everything was just going into the trash.

But the second day I was walking around and something just clicked. All of a sudden I had all these new stories flood my brain. They're all fiction, and I've worked a lot in nonfiction so it's really wonderful to be able to just make up these stories and go for walks with my characters and have conversations with them. That was a really healing experience, and it allowed me to also set aside the project that was supposed to be a collaboration, which I do want to come back to when it's not so close to the breakup.

What was it like putting together the board that would help move Short Run into the future?

Kelly and I had a lot of conversations about who would be a part of it and what they would contribute. I think that the board she's chosen is amazing. All the people are super-active and they know a lot about nonprofits, and about the comics world, about art. It feels really solid.

What part of your time at Short Run are you proudest of?

I'm really happy about the smaller programs that Short Run has built. Everyone thinks of the festival and it's this huge event where we have, you know, thousands of people attending and it fills all of Fisher Pavilion. We have 300 artists, and so it's like this big dramatic thing.

But we also have all these smaller programs — we have the Micropress which publishes anthologies; we have the Dash Grant, which is a small grant for self-publishers; we have our educational component. And we also have the Trailer Blaze, which is the ladies comics residency at Sou'wester, which is a vintage trailer park in Seaview, Washington.

That residency is for women comics creators, and that was really important to us because when we first started Short Run, it was a lot of dudes. I remember when Kelly had to make the table map and she had to lay out where everyone would sit at the festival and she'd put three guys and then one woman and three guys and then one woman. It was just so difficult to figure out how to show representation of women.

That is absolutely not true anymore in any way. It's so easy. We're basically 50 percent women and it's not hard — it's not like we're trying anymore. There are so many more female creators in the field. So anyway, the residency is for women comics creators. It's so wonderful because it's a combination of giving women time and space to dedicate themselves to their work, which we often don't have in our daily lives because we have so many distractions.

It's just a very supportive environment. I remember one time at Trailer Blaze in the first year. Without any urging of any kind, we started this thing that we later called "The Compliment Avalanche," where we just went around and told stories about how wonderful the people were. Each woman got to be spotlighted for a few minutes, and it was just such a wonderful loving experience.

So what are you working on now?

Right now I'm working on a bunch of stuff. I just finished a minicomic that's actually an illustrated zine called Vantage #3, and it documents all the walks that I did during that residency I was just talking about at Caldera Arts. While I was there I was really inspired by the environment — both the natural world and the actual space that I was staying in, the A-frame cabin. I wanted to incorporate that into a story, and I wasn't quite sure what I was going to do when I set foot in the A-frame cabin, but I immediately fell in love and realized 'this is a character in this story.'

I think after #metoo, everyone was trying to find an authentic way to talk about how misogyny is rampant in our culture. I wanted to create a story about it, and I wanted it to reflect my personal experiences but also be fiction. And so I started out with this woman who basically goes and lives in this A-frame cabin. She's trying to get away from all the men in her life. She starts having conversations with the environment, with the natural setting and with the cabin, and they become characters on their own and they develop.

She develops a relationship with space that becomes more intimate than her relationships with men, and more loving. And that's as far as I can go into a description of that without giving it all away.

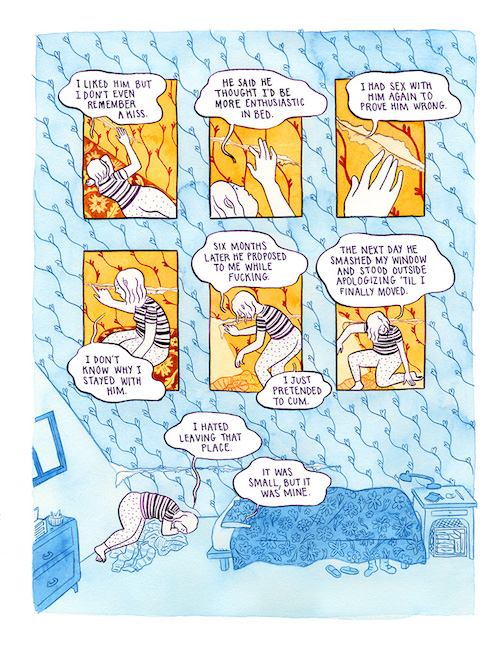

A page from Vantage #3.

It seems like a lot of your work, especially Detained, is about people in space — where they are and how those places affect them and how they affect where they are, and all that. So it seems like this is a continuation of that theme on a very literal level.

Yeah.

Does it feel like working in fiction has enabled you to get a little deeper into those themes?

In some ways, fiction makes it so that I can be almost more intentional in the purpose of the story. When I'm drawing from my own life or from non-fiction stories, I'm indebted to the people who are a part of it. With fiction I can go in any direction I want to. So it does free me up to explore different themes that maybe aren't going to be present in every story. I feel like there's a lot of freedom in fiction that I haven't paid attention to in a long time.

Are you going to still go to Short Run this year?

I'm definitely going to Short Run and I'm going to be tabling for me and Kelly as usual. And of course I know all her books so I'll be able to sling them pretty well. I definitely imagine that I will be a part of Short Run and all the events that the organization puts on. I've been going to the Summer Schools that are going on right now.

They put on amazing events! They just do such a good job, of course I'm going to be a part of it. And some of my best friends are the fantastic women who are the building blocks of this organization. So I'll continue to be in their lives and in Short Run's life forever and ever and always.

Was there anything else you want our readers to know?

Yeah. I'd like to reiterate something that I said in my retirement letter, which is that Short Run will exist without me, but it won't exist without all you. People need to support this organization that has affected their lives. Maybe that's coming to events. Maybe that's donated time. But especially right now the organization does need support, so please give whatever you can in whatever shape or form it takes. I want to see it continue for another decade.

An exit interview with Shin Yu Pai, the outgoing Poet Laureate of Redmond

What does it mean to represent a city, or a state, through poetry? To me, the role of poet laureate always felt like it would be too much responsibility. Writing a book of poetry is one thing, but to represent the varying perspectives of a community through poetry seems like a daunting task of representation. Seattle poet Shin Yu Pai talked to me over the phone last month about her tenure as Redmond's Poet Laureate — what she learned, her successes and failures, and what she thinks her legacy might be. To learn more about Shin Yu Pai, including samples of her work and upcoming events, visit her website. She reads next at Elliott Bay Book Company on Saturday, January 13th.(Photo of Shin Yu Pai at the "Heyday" video unveiling by James McDaniel.)

You're one of the most thoughtful poets in the Northwest, and I was wondering if your term as Poet Laureate of Redmond provided you with any insights into what being a poet laureate, what representing a city as a poet, means to you. What did the experience teach you?

I learned a lot about what the work of doing public art is like, and what skills are involved in doing that. I worked collaboratively with individual artists and designers, and even companies. Working on a larger scale — working with a community or city — was a new kind of experience for me, and I found that there were different kinds of skills that needed to be brought forward in my own work and ways of managing projects that I needed to be more flexible with: scopes of projects, timelines, and so on.

Those are the things that, over time, informed the way that I went about the work. I made certain pieces knowing what kind of iterative processes they might need to go through before they could be presented or shared. Those were good lessons for me, because for a work to really reflect a community — and for a work to be conversation and collaboration — those things take more time, and a lot of back and forth.

A lot of your work in this project has involved nature. I’m thinking of the leaves and your animated poem “Heyday,” about the Redmond history of logging. You know, nature is probably not in the top three things that a Seattleite thinks of when you ask them about Redmond.

So Seattleites probably think of Microsoft and rocket technology when they think of Redmond. And those things are absolutely true, and they're stereotypes, too. They've still got farmland [in Redmond,] and there's still parts of it that feel very unspoiled to me.

For me, exploring Redmond became this exercise in really wanting to see what the city is: its history, its place. Certainly there's the city — the contemporary technology and what makes it the place that it is now. But I wanted to very much ground that with the physical geography of what Redmond is.

And that’s what drew me to the bike trails, and really interpreting the history and what the city is known for in terms of its archeological significance, alongside famous residents and contemporary people who were important to this city. That was a very intentional gesture, looking up historical records to really look at the past of Redmond, and bring it alive and animate it.

I didn't really have many thoughts about Redmond when I moved here because I don't drive, so I almost never made it out there. But then I started walking, and I wound up walking to Redmond a lot, and I really dig it. I like all the bike trails, and then as I've learned more about it I like what I’m learning. The mayor has been very progressive, and very interested in making the city ready for transit, in a way that other communities outside of Seattle haven't really done. And politically, of course, there's Manka Dhingra, who’s just turned Washington state’s legislature blue for the first time in a while. It’s interesting to me that you don’t live in Redmond but you’re representing Redmond. What was your exploration of the city like?

Yeah, so, it's been a series of visits. Usually they’re built around exploring a certain site. The Heron Rookery was one place that I harvested leaves from, and the Farrel-McWhirter Farm Park. And I also explored the organizations that are there. I've had a couple of really great partners in the Redmond Public Library, in VALA Eastside, in the Senior Center. It’s been a slow and gradual exploration from a distance.

I will admit, honestly, that I think that living here in Seattle — and I don't drive much either — it was a challenge to be more deeply immersed as a Poet Laureate. And I actually think that as they're looking for a new Laureate, they should probably consider somebody from the eastside.

But, I don't think that was necessarily a barrier or deterrent in eventually hitting my stride

One of the things that I did last year for National Poetry Month was to curate this celebration of poetry and song. And so, I brought together people like Jessika Kenney to perform traditional Persian and Middle Eastern music with a performer from Kirkland named Srivani Jade who sings Mira Bai poems.

And it was really exciting to see that the audiences that were coming out for some of these programs were quite different than what you would see at Seattle openings or Seattle readings. Redmond is a city that is very much made up of many immigrants from Southeast Asia, and it was really great to be able to draw some of those folks out with some of those things I'm trying to do.

You've always been a very collaborative artist, but it seems to me that the act of being a Laureate involves a sort of elevation of other artists. Was there a learning curve to finding people and to curating the Laureate experience?

Yeah, certainly in some of the technologically sophisticated projects I wanted to do. I collaborated with the textile artist, Maura Donegan, who is from the east side, on this poetry embroidery project that was a response to a hate crime that happened in Redmond. And it took me a while to find Maura, because I had sort of gone down this path of wanting to figure out a way to digitally fabricate the piece that I made that was basically an embroidered broadside in multiples. But that was a very complicated and expensive process, so ultimately I engaged Maura to just make me one big textile piece that she basically sewed herself.

It was a challenge to find her, and VALA Eastside really helped to direct me towards her. And, with this last piece that I'm doing — this video projection — it took time to figure out who had the technical knowledge. I needed to find a designer who could do animation, and then I needed to find somebody who could help me with the logistical specifications of projecting onto the side of a building at night. So, I've been really lucky through Seattle networks to know who those go-to people can be, to help me create that work.

So, the learning curve, I would say, was pretty steep. Because there are lots of people that I know in my creative network here, but I also felt like the particular projects that I was working on required a certain kind of sensibility.

I wanted to ask you specifically about the textile work, because I don't know if I have seen other Poets Laureate be that, sort of, immediate? It seemed, to me, to be a mix of poetry and visual art and journalism. What a Poet Laureate should do is console in times of tragedy and investigate what the tragedy means to the community. And that seems like, just such a unique moment and unique piece.

Yeah, I'm really grateful that you asked about it. It's a piece that's important to me, and I wasn't able to share it or fabricate it for over a year.

So, I wrote the poem in early 2016 — I want to say in January or February of last year. It was this a crime that you may have heard about in Redmond. It involved a woman named Leona Coakley-Spring, who is a Black business owner and had this small consignment shop, which was called Rags to Riches.

She was running her business and there was a young man who came in, acted really suspiciously, said he wanted to consign some clothes with her. He ended up leaving, and he left behind a couple of garments in bags. And so when she went to look through them to try and identify if she could return the materials and garments to him, she wasn't quite sure what she was looking at. But when her adult son came and looked at the materials, what they discovered was that this young man had basically abandoned a Klu Klux Klan robe.

That was this really, really heavy thing. I remember reading about it in the news and being so shocked and appalled — that in this present day, so close to where I live, that this was happening.

Yes.

And, you know, a KKK robe is a very potent symbol whether or not you're a black person or not.

And it's such a specific crime, with such a personal level of premeditation to it There’s such a weird intentionality to it. You know, you hear 'hate crime' and you think of, like, graffiti or something impersonal like that, but this feels so direct.

It was very threatening. It was very disturbing to me. It was this clear message of like, "Go back to where you come from." You know?

And so, it really demanded or called in me this reaction to express some sort of solidarity or compassion — some kind of response. And so I wrote this poem and I hoped to share it with the community at that time, but because this was under investigation and the poem included details of what had happened, the city determined that we couldn't share it with the public, because it was an active crime investigation. And that investigation went on for a few months, but ultimately they weren't able to track down the individual that left those items, and Ms. Coakley-Spring ended up closing her store, and the robe was somehow returned to her. I don't know if it was taken in as evidence for a time or if she always had it, but I read a story in the news about her burning it.

That was this really powerful moment too, because I had had this whole plan that I would try to connect with her and ask her if I could have the robe so that I could embroider it or do something with it, and use it as kind of the basis of the response that I wanted to make. And so that didn't work out.

I thought about an embroidered broadside, and that didn't work out budget-wise. And so then, we made the textile, and that was actually shown this summer at the So Bazaar Festival. I partnered with VALA Eastside, which is this gallery in Redmond, and we talked about the idea of putting together an interactive poetry embroidery booth. We wanted to use the broadside that Maura and I had made together as kind of an example of what people coming to the festival could do. They could sit down at this booth with embroidery hoops and cloth and thread and needles, and basically do embroideries themselves and come away with something that they could take home or feel proud of.

And so I curated language out of Redmond's Inclusion Resolution, and I also took language from poems by Elizabeth Alexander, who's a former Obama inaugural poet, and Langston Hughes and some others, that all dealt with inclusion and tolerance in some way. And then we basically mocked them up so that people coming to the booth could stitch those as kind of their sampler. The intention behind the booth was very much to engage regular citizens in this specific dialogue around inclusion.

Exit Interview: Michelle Peñaloza says goodbye to Seattle

Michelle Peñaloza has lived in Seattle for almost exactly four years. In that time, the poet and essayist — she’s the author of the chapbooks landscape/heartbreak and Last Night I Dreamt of Volcanoes — has become a ubiquitous Seattle literary figure, both on stage and in audiences at literary events throughout the calendar year. Peñaloza's announcement that she will be leaving town at the end of February sent a shock through the community. She’s more than just a sharp observer and a deft and graceful poet — though she is that, too. She’s become an integral part of the literary community’s support system. It’s hard to imagine the city without her.

Peñaloza made time to talk over the phone in the middle of a very busy transitional week in her life. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Thank you for making this time for our readers. I really appreciate it; I know it's a very busy time for you. I guess, first of all, I am wondering if you'd be willing to talk about where you're going and why.

I won't get too specific, but basically I'm moving for love, so that my partner and I can be together full-time in California. That's reason, I think, to leave.

So say somebody in California asks you what the literary culture in Seattle is like, and what your experience has been. What do you think you'd say to them?

It's a very vibrant scene. I would say that I was very sad to leave it and that I've loved my time in Seattle. I've met so many incredible people, and I feel like I've been lucky to have such a great amount of support. Not that I don't work hard or anything, but I feel like I've been very supported as a writer in Seattle. I feel like I've had a lot of opportunities with Jack Straw and the Made at Hugo House Fellowship, and teaching at Hugo House. I was a visiting writer at Seattle U. I would say that my personal experience has been a very good one.

So you would recommend to Seattle to another writer who's asking your opinion about whether she should move here?

Yeah, it's the best city that I've ever lived in as a writer. Granted, part of that is where I am in my writing life, too. I finished grad school maybe two years before I moved here, so I was in a different spot than I'd ever been in my writing life. I think those just dovetailed in a very fortunate way for me in Seattle.

Also, I feel like it's big enough that there's lots of stuff going on. In fact, sometimes too much stuff going on. I feel like there's some months in Seattle that are just insane — like, October is always crazy because people have been coming down from summer. There's just reading upon reading upon readings.

I would say, I guess, if you're looking not to be too busy, I don't know if Seattle's the place for you.

Is there anything that you think that Seattle could do to be more supportive for writers?

One of the things I noticed when I first moved here, and then I sort of became part of that same pattern that I had noticed, is that a lot of Seattle readings series ask the same people to read. You'll see someone who's reading everywhere all the time for like a year. I feel like maybe spreading it around more, doing a better job of thinking like, "Oh, I just saw that person read. Maybe I should save them for later."

I feel like I've been that person before, where people were like, "There she is again! Geez, she's everywhere." I don't want to sound ungrateful, but I also think that a way to be more supportive of writers in general in Seattle is to not always have the same people read.

One other thing I would say is to organizers who run reading series or do anthologies or any sort of curation of writers is: try hard to make sure that if there are five readers in an event, don’t choose four white people and one brown person. Make sure that there’s always more than one person of color reading at an event.

You have so much geography in your work. Place is essential to your writing and I'm wondering if you thought about how moving from Seattle will affect your work or if you think Seattle is going to be represented in your work in the near future.

Every place I've lived has sort of made a mark, but I think Seattle will always be a part of my writing, whether or not it is obvious. Because I feel like Seattle's the first place, personally and professionally, that I ever felt fully myself. I know that sounds sort of lofty, but when I first moved to Seattle, I had just come out of pretty traumatic personal — for lack of a better word — shit that I was dealing with. I was escaping a lot of things.

Seattle was a city that, personally and professionally, welcomed me with open arms. I know that that's not necessarily a typical experience — people talk about the Seattle freeze, and they talk about how the literary scene can be hard to break into, but Seattle has been so special to me in that way.

Then, also, I met such incredible people here. It’s just a really close community of writers that I admire and that motivate and impress me.

Do you plan on coming back and reading anytime soon?

I don't know about readings, but I will be back this summer because I'm going to be teaching a Scribes class at Hugo House with Imani Sims, which I'm really excited about, but I don't have any readings or anything lined up.

Was there anything that you've been thinking about in these last few weeks as a Seattleite?

I guess what I would say is that I'm going to really miss Seattle. I think that's apparent from what I've been saying. But I also am excited to begin a new chapter of my life with my person in a different place where we can be together all the time.

Seattle has been a real home for me. I will be really sad to leave it but I've built solid relationships with people and with this city that I feel like I could come back and be welcome again. I guess I just want to say thank you.

Exit Interview: Kelly Davio is moving to London

Where are you going, and when and, if I may be so bold, why?

I’m gearing up for one of the bigger moves of my life: I’m headed to London, England. My husband is in tech, and his company has made him director of a group that works primarily out of its London office. It’s hard to say goodbye to literary Seattle, but I’m awfully proud of my husband and this big opportunity for him, so off I go. If I can get all my paperwork in order, that is. Trying to collect all the right papers, stamps, and certifications feels a little bit like waiting for a ruling in Jarndyce and Jarndyce, if I may be allowed a cheesy Bleak House reference.

We encourage as many Bleak House references as possible around here. When do you leave?

If I can get all of the moving parts of this relocation to align, I should be gone by early October. Somehow, in this remaining month-or-so, I need to sell a house and find a new apartment overseas. Yet somehow all I want to do is work on my novel revisions. Maybe I'm in denial!

How would you describe Seattle's literary culture?

I’d say the community here is pocketed. And I mean that in a good way — there are wonderful little pockets of literary community all over the city and the larger area, and no matter what neighborhood you live in or what kind of literature you like to read or write, there’s a gathering and a community for you. Over the years, I’ve thought, “okay, now I have a handle on literary Seattle.” Then I'd immediately be proven wrong when I’d learn about an expo like APRILFest, or about events like Poets in the Park out in Redmond, or about cool new presses like Two Sylvias, or about great literary organizations like Old Growth Northwest. There’s always something new percolating here, and I’ve loved discovering all of these diverse and thriving literary communities over the past decade.

Did you feel supported in Seattle?

Absolutely. Part of that comes from having attended Northwest Institute of Literary Arts, which I firmly believe to be the friendliest and most supportive MFA program in the world. Part of it's also the fact that literary folks in Seattle are unusually giving of their time, their knowledge, and their professional support. Every time I’ve needed help with setting up a reading or getting in touch with a conference organizer, a fellow poet or writer has been gracious enough to help me out. I’ve tried to do the same for others in turn. I think Seattle writers understand that the literary world is an ecosystem, and that when we all work to better that ecosystem, we create a better place for all of us to thrive.

In your opinion, what could Seattle literary culture do better?

We could — and I include myself in this — put our butts in chairs with greater regularity. Being an attendee at a reading series, a book launch, or a workshop is an important way that any one of us can support other writers. Of course, it’s hard when you don’t get off work until six or so to make it halfway across the city to attend a reading at seven, especially when traffic is grueling and busses are late and it’s raining, and, and, and. Yet at the same time, it’s awfully disheartening for authors to put on events that draw, say, two people total.

When a good friend of mine released her first book a couple of years back, she had a big, well publicized event here in Seattle, and just one guy showed up. The guy wandered in as she read to an empty room, he ate a muffin in what sounded like an arrestingly messy way, and then he wandered back out. That, folks, is a bad scene.

And where the heck was I? I don’t remember. I will always feel terrible about not showing up and putting my behind in a chair to listen to her and support her.

Are there any aspects of literary Seattle that you'll especially miss?

I’ll really miss Open Books, Elliott Bay Books, and Hugo House. Those places — both as physical locations and as evolving communities — have been at the center of my experience of Seattle as a literary city, and I’ll miss being able to pop by anytime I want.

I’ll also miss being close to home base as I work on Tahoma Literary Review; I’ll continue as poetry editor and co-publisher, but it will be a bummer not to be able to attend contributor readings and launch events here at home.

Do you have any readings or public events between now and when you go?

I do! I'm happy to say that I'll be reading one last time at Lit Fix on September 23, 7pm at the Rendezvous. I'll be reading with Kevin Maloney, Matthew Simmons, and Jeanine Walker. All the proceeds from the event will benefit Literacy Source, which does wonderful work here in our community.

Do you have any parting words, advice, or wishes for Seattle's literary scene?

Be good to each other. Remember that there’s room in literature for all of us, and we’re at our best when we help — not crowd — each other out.

Exit Interview: Talking with Kate Lebo about why she left Seattle for Spokane

For many years if you attended a reading in Seattle, you'd have a pretty good chance of running into Kate Lebo there. The author of Pie School: Lessons in Fruit, Flour, and Butter and A Commonplace Book of Pie, Lebo is a poet and an essayist who's read on pretty much every stage in Seattle. But unlike a lot of writers who only show up when they're on the bill, she's always been a full participant in Seattle's literary scene, too. She goes to readings as an audience member and participates happily in group readings and festivals and the daily writing life of the city; all of which is a long way around saying that she always seemed like a lifer. So I was shocked when I heard that she'd moved out of town. Lebo was kind enough to agree to a conversation about why she left.

Where are you now? What are you doing?

I live in Spokane, Washington, but I moved there about six months ago. Before that, I was living in Vancouver Washington for two years. I did this kind of French exit from Seattle when my rent went up like crazy in the middle of a book project. I set up house in my parents house — actually my childhood bedroom — and set up a bunch of house gigs and tours and did things to try to only be home about half the time.

Now that I have my own great adult home in Spokane, I’m still touring about half the time. I’ve been trying to balance freelance work — teaching creative writing and writing things and teaching pie and doing events for the two cookbooks — that translate to paying my rent and getting to be free. I decided not to go the academic route and I decided not to go the Amazon route, but it’s left me vulnerable to the vicissitudes of a freelance life, which I’m sure you know is feast or famine. And Seattle became a place for me where the famines became too deep and the rents and the cost of living were too high for me to live there.

I didn’t want to go, because [Seattle is] where I came of age, and I’ve got such deep personal and professional and artistic ties there. I’m trying to keep them by appearing like I didn’t leave, like not telling people where, exactly, I am at any given time and just being in town a lot.

Why did you choose Spokane?

I fell in love and he works for Eastern [Washington University]. So it was a good choice for my personal life. And when I was looking at Spokane, I realized I can get a really cute apartment for exactly half what my rent was in Ballard, which is the last place I lived in Seattle. The cost of living is cheap. It feels a lot like Bellingham to me; I went to college in Bellingham, which is why I’m making that comparison.

People value the arts in Spokane, and they’re super-hungry for more, but they don’t get as many touring acts coming through as they do in Seattle. There’s not as much money here. There’s not nearly as much money as there is in Seattle and Portland. So that means it’s easy to live, in that I can be a freelancer, I can be an artist, and I can live like a real adult. It’s also a more emergent place where there’s less money being passed around for the creative things that you’re doing, and I think there’s a little more work to do in educating people that it’s valuable to spend your money on really good food, that it’s valuable to spend your money on art.

What I’m discovering is that because there’s less money there’s a lot of hunger and a lot of openness. It’s the kind of place where you can say “I want to do this thing,” and then you can go do it and then everyone shows up and they’re really excited that you’re there. It’s really cool how easy it is to make something happen.

What’s also funny to me was when I told people in Seattle I was going to Spokane, the responses were kind of formulaic: "why would you go there? I’ve been there and there’s nothing there." Most of the people who told me that hadn’t been there in ten years.

And then the other thing people said was, “maybe you can go start an art scene there.” Which was hilarious because they had this kind of pioneering attitude, assuming there’s nothing there already. There’s been a thriving art scene [in Spokane] for a while. Jess Walter’s there. There’s tons of writers: Kris Dinnison, Sharma Shields, Tod Marshall, Sam Ligon (my partner). There are three universities. WSU is building a medical school there.

It’s funny to me that it is a place that west-siders assume is backward and rural and small. It’s bigger than Tacoma, it’s educated. There’s a certain kind of east-west polarity that’s like US vs. Canada or Australia vs. New Zealand. The big dog has to have an underdog to reinforce their image of themselves, and what that creates is an ignorant assumption about a place that is actually pretty cool.

How would you describe Seattle’s literary culture?

I knew you were going to ask that question, and I don’t have a good quick answer. I moved to Seattle when I was 22 years old from Bellingham, and I knew that if I went to Hugo House, I would find my people. I’d find a place that would not only give me an education, but it would give me a community and an identity. I wanted that, I needed that, and I found that. That is a resource that is rare among cities. I owe a lot to it.

And what I saw over my decade in the city was a lot of different ways to participate — people feeling like outsiders and finding a way to create their own way to participate. I saw a lot of different people say, ”the place where I would be most excited to be a writer is missing, so I’m going to go make it.”

When you get to a smaller town, there’s a weekend where everything is happening and then there’s three weeks where nothing is happening, whereas there’s always something happening in Seattle. And I actually got to a place where I needed to hide from all the brilliant things going on [in Seattle] so I could do my work and be well and not suffer from burnouts constantly. So in some ways it’s been incredibly great to leave and be able to return on my own terms, in my car, for pleasure and business.

I think in Seattle when it doesn’t feel like there’s room for you, people elbow in and make room, and I like that and I admire it. I think there’s a competitive feeling and it’s used by a lot of different people in a lot of different ways.

Have you done that in Spokane? Did you try the Seattle approach and how was it received, if so?

I’ve been wary about trying a Seattle approach, which I would interpret to be showing up and saying, “hey I know all these cool writers you’ve never heard of so let me bring them in from the west side.” I’ve really been careful about not being a jerk like that. I hope.

It’s easier for me to imagine taking risks with business, with artistic ventures, in Spokane than it was in Seattle. I find that when I’m in a competitive environment I prefer to absorb and participate but not to lead. In Spokane, there’s more room in a way that for me personally feels open to leading and creating.

For example, I’m now teaming up with a sommelier and restaurant owner and a beloved bartender in Spokane to do a series of dinners with artists in unlikely locations around the inland Northwest. We’re going to have Alexandra Teague at our first one. It’s going to be awesome. And I wouldn’t imagine doing that in Seattle; not because I couldn’t — there’s brilliant cooks everywhere and there’s brilliant writers everywhere —but just because there’s already so much happening that it didn’t seem like whatever I would come up with in that way was really needed.

Did you feel supported in Seattle?

There’s two versions of that answer. One is unequivocally, deeply, yes. I loved working at Hugo House and finding a helping role that also educated me, about what it was to be in an artistic community, all the different ways to be an artist. One of the reasons I didn’t pursue an academic career was after Hugo House, it was just clear to me that there are so many ways to do it. It made it clear that I could go teach pie classes and do that instead of trying to go get a fancy fellowship.

A woman I knew through Hugo House who works for Amazon very kindly tried to recruit me when I graduated from UW. I didn’t take that job because it seemed to be cross-purposes to writing books, which I what I wanted to do. Saying no is a privilege, but it also leaves me vulnerable to the people who say yes. That’s the person who was able to rent my apartment when the rent went up by 50 percent six months later. I think about that choice. It was the right choice.

I don’t know if it’s the right word, but I felt disenfranchised — living in a city for that long and looking around and just knowing that I’m never going to own a piece of this place. With what I want to do, I will always be borrowing space, and that makes me vulnerable. Even though I participated in the cultural life of the city, and contributed for years, what I needed to succeed was participation in the financial life.

And so in that way, no. Not supportive. I don’t have a good answer for what the city is supposed to do about that. I was just reading an article in the New York Times about the Seattle Art Fair and how it happened and one of the reasons it happened is because the city is getting richer faster than anywhere else in the country.

It’s not your particular value as a person that’s going to bring you success, it’s the amount of resources that are available. I’m taking this course on the history of food right now and what you see over and over is that a population explodes and a people become complex not because they’re such a good people but because they’re geographically in a place that gives them more resources that allow them to grow. Seattle’s dealing with an embarrassment of riches.

Where are we going to live, so that we can make art in the city and have lives that are reasonable, that we have reasonable expectations for our lives, have some comfort? Can we make the choice to be artists and not live in abject poverty? I know being an artist isn’t going to be as comfortable as working at Amazon, but for me it was such a clear thing.

I chose to be an artist, I had to leave the city. There’s not a reasonable way for me to make a living and pay my way in Seattle. I needed to go to a smaller place.

[Before I left,] I was approached by the affordable housing association in Seattle and they had some options, but they not reasonable for me. They were still fifty percent more than what I’d been paying. I’m frustrated with the idea that artist housing is going to solve the problem of livable places for artists to live. It’s just another thing for us to compete for. A different person would respond differently to that, and elbow to the front of the line, but my response is just to leave.

Would you recommend Seattle to another writer? Say a young writer from Spokane approached you and told you they were thinking about moving to Seattle. What would you say?

Oh, yeah. You should leave wherever you’re from, for a little while, anyway.

Part of my decision is that I’m in my early thirties and I want to live my life differently than I did in my twenties. I’m not as good at living poor and living hard as I used to be.

I would also give people the advice to look to unlikely places in Washington and Oregon for really cool artistic communities that you wouldn’t expect to be there. I’ve been doing a ton of travel around Washington state. Even in Wenatchee — holy crap, talk about a place I had really dumb assumptions about — they have great restaurants and shops and a great artisan scene there. I’m not saying “move to Wenatchee,” but I’m saying keep your eyes peeled for places that have the resources and the people to help you get the things you want.

Kate Lebo will be in Seattle next on September 16th, when she reads at Hugo House as part of the Wage Slaves reading series. Follow her comings and goings at Katelebo.com.