Archives of Interviews

Franklin Foer has advice for any city looking to become Amazon's second headquarters

Franklin Foer’s World Without Mind is a must-read book of the fall season. Subtitled The Existential Threat of Big Tech, World is a full-frontal assault on the fallacious idea that the big four tech companies that shape our world — Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple — are benevolent firms that have the advancement of humanity in mind.

Foer smartly couches his polemic in memoir, relaying his experiences as a beloved editor of the New Republic. When the storied magazine was bought by a tech gadfly, its century-old dedication to the art of journalism and thoughtful opinion was discarded in favor of click-hungry content farming. Foer was fired, and the majority of his staff left with him in solidarity.

A lesser writer could seem like an aggrieved party in World, and Foer certainly does acknowledge that his pride was wounded in the aftermath of the New Republic’s Silicon Valley-styled meltdown. But instead he makes a compelling case for considered, intellectual thought in the public sphere, even as he rages against the slick digital robber barons who have consumed our attention in exchange for a few baubles of convenience.

Foer reads from World at Elliott Bay Book Company on Wednesday, September 27th at 7 pm. The event is free; no purchase is necessary. I hope you'll go hear him out. You’ll likely think a little differently about the urgings of the vibrating hunk of glass and steel in your pocket after the event.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of a phone conversation I had with Foer last week.

I assume you heard the news that Amazon recently announced that they're looking to found a second separate-but-equal headquarters in another city?

Yes.

Now we're watching cities bow and scrape in the hopes of bringing Amazon to them. Tucson just sent a giant cactus to Amazon management, like some sort of a weird dowry or something. I was wondering if you had any advice for cities that might be trying to entice Amazon to set up in their city?

Let's just look at Amazon's track record when it comes to exploiting civil government. Part of its business model has been to fleece local municipalities — with its refusal to pay sales tax over time, or all the concessions that it extracts when it goes about setting a warehouse down.

I think the right metaphor is the sports stadiums that get built in cities, where owners come in and exploit civic pride and sense of civic purpose in order to get these fantastical deals for themselves, where cities empty their coffers in order to build these monumental facilities that teams then make money off of.

I just think it's sad. And part of the sadness is that we can see where this is going over the long run, which is that Amazon may bring jobs in the short term, but they really don't want those jobs over the long run. In the long run, when Amazon puts down a warehouse, it's going to automate it, so there are not going to be workers.

I wonder whether these cities are doing anything to remotely try to calculate the long-term economic benefit for themselves. I doubt it.

One of the things that I thought was especially interesting in this book was the writing about media, especially the parts that focused on your own experience. I left a publication soon after management installed [analytics software] Chartbeat because they devalued arts coverage after they learned that it wasn't as popular as they had assumed it was.

I've done a lot of thinking since then that maybe the original sin for the marriage between media and the internet was the decision by Google founders that a click on an ad was only worth a fraction of a cent. It's a system that doesn't allow for the fact that some clicks could be worth more to some advertisers than to others. It's very rigid. Do you think there's a way to change that discussion — to revalue the importance of writing as valued by advertising — or is the advertising model basically dead for media?

My sense is that the advertising model is kind of dead in the short term. I fundamentally agree with you that Google has deflated the advertising market as it exists now beyond any reasonable significance to media companies. We need to move on to something different.

My preference is to move to a subscription model, but I also think that it's possible that there's some form of advertising that hasn't been invented yet that could be more valuable than display advertising, and less corrupting than the native advertising that we've seen people moving towards over time. But I'm not smart enough to know what that is.

Do you think anyone's getting close to it? Do you see anybody doing things that you like?

What I like is the resurgence of subscription models. I like that the New York Times and the Washington Post seem to be selling subscriptions in some volume, re-acclimating people to the idea of having to pay for what they read.

But I also think that the subscription model as it exists now for digital journalism isn’t valuable on its own because the prices are set far too low. We're kind of in this place where everything has been deflated. The value of digital advertising has been deflated, the value of digital subscriptions has been deflated, and it's hard to see where exactly the fast-forward is.

One thing that I do think -

Sorry that I don't have the cheerful, optimistic solution for you.

It's okay. Nobody has those solutions, that's the thing. That's why it's important to keep thinking about it. But one thing that I do think the internet has done really well — and I don't know if it gets a lot of credit from people in the media on this — is to provide a platform for people who have never before had voices in the media.

Yes.

I find it really difficult to argue for a return to the old gatekeeper model when there's now more representation in culture than ever before. Is there a way to reclaim institutional thought and consideration while still maintaining the representational progress we've seen in the last 10 years?

Yeah. That doesn't seem terribly difficult to me. I think that institutional journalism has responded to the internet, and also a shift in times, by being much more representative. I think that when it comes to a lot of these questions about new technology and old media, it's easy to slip into Manichean thought. The choice isn't between going back to the old media of the 1980s — which was stodgy, excessively white male, etc. — versus the status quo. I think we have the ability to do better on all fronts. I don't think that we need to abandon all the good aspects of change in order to respond to the bad aspects of change.

As you were collecting ideas for this book, where did you draw the line between reality and conspiracy theory, and between apathy and malevolence in the intent of these companies? It's very easy for me to get too wrapped up in this sort of good guy/bad guy paradigm, when the truth of their intent is much more complex. Is this something you've had to think about as you’ve put this book together? This is kind of a vague question and I'm very sorry — can you retrieve anything of value out of that?

I think you're saying that it's possible to look at what the tech companies do and come to the conclusion that they're highly malevolent, when in fact they may have a lot of ideas that could be caricatured as malevolent, but in fact are relatively benign. Is that what you're saying?

Yeah. That's a good, solid place to start for sure.

I would say that what makes these companies interesting is that they're idealistic and ambitious. I think one does need to take seriously their own self-description. I think that we need to treat them as not just money-making corporations, but treat them also as companies that have ambitions to change the world. Sometimes they're self-justifying ambitions. I think that [Facebook founder Mark] Zuckerberg does a lot of self-justifying, but in other instances I think that they're perfectly sincere in describing how they want to change the world.

[Calling it] a conspiracy makes it sound like people are sitting in a back room somewhere in Palo Alto devising a hidden plan. My point is that the plan isn't actually very hidden. I think that a lot of times these companies, for the most part, are very naked in describing what they're up to, so I don't really think it takes a whole lot of reading to go to the place I go when I'm describing them.

Do you worry when you put this book out that there's a chance that you might be pigeonholed in the role of the curmudgeon — like, CNN will call you to fill out a panel whenever they need someone to just complain about Big Tech?

Yeah, I've clearly cast myself as grandpa. I don't understand why that's a worry. Am I worried that I'm a token, is that what you’re asking?

The media tends to find value in people who say “no,” but they value them only if they say “no” in the same way again and again. I wonder if there's a possibility of you being typecast as the man who said “no.”

I feel like I'm just writing my opinion. Really I wasn't thinking about being on a CNN panel when I was writing about this book. I want my argument to be heard, so I'd probably go on a CNN panel, but really I live to write books and arguments, not to be on CNN panels, so that's what I think about most.

Do I worry about getting typecast as a curmudgeon? If that's your question, I clearly don't really worry about that because I wrote a book that can easily be described as curmudgeonly.

What has the response been like at your events? Is there anything that you think that people can expect coming out to your reading in Seattle?

One of the interesting things in the moment that we've arrived at is there's this concept that's become cliché in describing our politics, which is this concept of the Overton Window, which is when the discourse expands to include ideas that resided outside of the mainstream.

When I started working on this book, I felt like people looked at me weirdly, and they couldn't understand why I was going to be criticizing these companies in technology that people have so much affection for.

Over the last couple months, I happened to make an argument that lined up with a shift in thinking. In large part, I think the election started to change people's minds about Facebook, and then Amazon's purchase of Whole Foods elicited a lot of anxiety about Amazon's size, and etc.

One of the fascinating things is that there are a lot of people who I thought would hate my argument. I've just been surprised at the people who are either centrist or in finance — or even in Silicon Valley — who seem sympathetic to my argument. It feels like I thought I was going to be throwing a stone at the Overton Window, but instead, it feels like I'm just climbing through the Overton Window just as it's opening.

When this cartoonist broke his right arm, he taught himself how to draw with his left

From his Punch to Kill comics to his work organizing the dearly departed Intruder magazine, Marc Palm is one of the most active members of Seattle’s cartooning community. So when Palm announced on Facebook earlier this summer that he broke his right arm — his dominant arm, the arm that did all his drawing — the community responded with a visceral heartbreak: one of Seattle’s most prolific and enthusiastic cartoonists was going to be out of commission for the foreseeable future. But then Palm did something unexpected: he taught himself how to draw with his left hand. I talked to him in late August about his experiences.

Thank you for doing this. I’ve been following along on your journey on Facebook and I think it's really fascinating. Let me start with a couple of personal anecdotes. I want to get your impression of them.

First, I had a friend who was an artist in high school. His mother likes to tell the story that when he was a kid he used to walk around the house with his hands in oven mitts. He'd hold his hands in the oven mitts right up to his chest because he was so terrified that anything would happen to his hands.

Oh, wow.

He identified as an artist so much that it was like a fear for him. He felt like he’d have no identity without his art.

And then second, my grandmother was born a lefty. At her school they tied her left hand behind her back until she became right-handed, because they thought left-handedness was a weakness of character.

Is she alive?

She died, a long-time ago. But she had Alzheimer's, and she actually reverted to left-handedness toward the end there. I thought those two stories might give you an idea of what I was thinking about when I heard about your story.

Speaking of which, I want to shut up and hear your story. So to start at the beginning, you bought a skateboard, right?

Well, no. For the last couple of years I've been getting more and more interested in skateboarding. When I was 12, my parents got me a skateboard — a big clunker. Then they got me pads and helmet and all this other stuff to be safe. And I tooled around in my driveway, which was the smoothest surface I had. But even then, I didn't wear gloves. I didn't wear oven mitts walking around or whatever, but I was a very careful child.

I've been a very careful person my whole life, really. So when I was 12 I was like, ‘You know. I think I'm gonna hurt myself. I don't really want to do this.’ Skateboarding was just cool to watch. I was gonna be a fanboy of it.

But then in the last couple years I was just getting more and more into watching it, and admiring it and thinking, ‘Wow, this is cool. Maybe I should give this a shot.’ So, [Seattle cartoonist] Ben Horak said, ‘I got this board I picked up from somebody. I'm never gonna use it cause I'm too scared to hurt myself, if you want it.’

He hands me off this skateboard. And whoever had it before, they actually were a skater. The thing was pretty well ground up, and it worked well. I was kind of tooling around wherever I could.

A couple of other cartoonists and started skating. They were very encouraging like, ‘You're not gonna hurt yourself. Don't worry about it.’ So we'd go find flat surfaces — tennis courts or parking lots or whatever. We call it ‘skate dad parks.’

That's where, inevitably, it happened.

It was the big Gotham Asylum up on Beacon Hill — the hospital up there. We found this great parking lot. No one bothered us. So I was off on one side, and they were on the other, and I just made this turn and there were some rocks, and I just stopped the board. And then I just landed directly down on my wrist, and that's when I eventually broke a chunk off the ... I forget what that is. It's one of the long arm bones.

I had never broken a bone, and I tried my best to avoid it. Until picking up a skateboard.

It was the worst fear that I had. [When I started skating,] other people were like, ‘What if you break your drawing arm ?’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, I know, but it'll be fine.’ Then the worst case scenario happened.

Just to get some background: you're a fairly prolific artist. It seems like you must draw every day, right?

Yeah, I try to. It's definitely in my blood. And I've been doing it for thirty-plus years — just constantly producing and trying to do my best. But I'm not gonna kill myself over a broken arm. I just started going down the process of seeing if I could draw with my left.

My mom has a similar story to your grandmother’s. She was a lefty. She went to Catholic school, and they bound her left arm and forced her to go right. She eventually, grew out of it and went back to being a left-hander.

But while raising me she forced everything into my right hand. She was hoping that I wouldn't be a left-hander because she thinks it’s a curse. The world is right-handed, and she didn't want me to deal with the same problems she had. It's possible that I could have been a left-hander, had it just come naturally.

After you fell when did your thoughts turn to the fact that this was going to really screw up your drawing? How soon was it before you realized?

It wasn't like a big revelation, but it was definitely like, ‘Ugh, fuck. I broke my wrist. I can't draw.’ It was immediate and I tried not to be too bummed out about it. I was more annoyed that now I'm gonna be completely inconvenienced — I only have one hand. I work at the Fantagraphics warehouse and my job is lifting up packages and packing things and now I'm kind of wrecked on that.

I just thought I was gonna have to take a break. Which stinks, because I have a book that I'm working on, and hoping to have done by Short Run. I immediately just realized I had to try to figure something out.

What did that process look like?

Oddly enough, months ago — maybe even a year ago — I was having a little paranoid fantasy, wondering what would happen if I couldn't use my right arm — if it got cut off or I broke it. I was just fascinated with the idea of what my left arm can do that my right can't.

So I tried buttering my bread with my left, and I realized that these two hands had no idea what to do when they're faced with something the other hand usually does. My right hand didn't know how to hold the bread properly, and my left hand didn't know the subtleties of spreading with a certain amount of pressure without stabbing through the bread.

I played around with that. I'd started to be more efficient. I’d remind myself, ‘why don't I just grab the door handle with my left hand because that's where it's at instead of reaching all the way over from my right?’ I was already trying things with my left.’ I hadn't really tried to draw or anything, but I farted around and, like, tried to write my name with my left. It never went well.

So then, a couple days [after I broke my arm] I grabbed a big fat pencil, and I thought ‘maybe I can come up with a cute style,’ because normally my stuff's grotesque. I thought maybe I could actually draw cute things with my left hand.

So I was drawing dinosaurs just to start out. They did look kind of childish, and it was hard to have the control that I wanted. But I saw that I could do something, so I just needed to focus a little harder.

So I changed tools. I went to the smallest micron pen I have. It's a .005. I started going really small and I found that when I was doing details with my left hand, I had a lot of control. But if I made big gestures, or made big strokes, it would get all wiggly and I didn't have the kind of control I wanted.

Wow, that is the exact opposite of what I would figure would happen.

I had a bunch of people encouraging me to try drawing with my left hand. At first, it kind of annoyed me. I was like, ‘You know, this is kind of a cute, fun thing to post online, but it kind of hurts.’

So after I did those dinosaur drawings I put one up right away. I was like, ‘All right, here you go. Everyone that says I should draw with my left, here's the drawings. Fifty bucks, let's go. If you want to support me, put your money where your mouth is.’

Yeah.

‘Or keep your cute little comments to yourself.’ All right, yeah, I could draw with my left hand. So then I just started working on it. As far as being an artist, you're basically dealing with like problem solving: ‘I've got a picture in my head. I need to get it on paper. How do I do that?’

And what was fascinating to me about doing this, was my way of working doesn't come from my right hand. It’s not the hand that does it — it's my brain. I can visualize where things have to go. I've studied enough brush strokes and different techniques. I just needed to be able to get my left hand become a good tool, to get those lines to flow the way I want to.

So yeah, I took my time and really had to be patient and focus on the circle, where before, my right hand had been doing it for thirty close years. I was struggling to draw these little things. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is what it's like for like a normal person who doesn't know how to draw. I could see why they give up. This is hard!’

I realized that this is an enormous amount of work.

It basically was just working through it — figuring out how delicate I have to be, how hard do I want to press on this, what kind of style do I want?

Now I see it as really cool and fun. I'm kind of addicted to it.

Do you draw every day now with your left hand?

Yeah. I go to a coffee shop and sit there for an hour before work and just draw. And that was a great exercise. Every day, I sit there and pump out a new drawing.

And all the drawings I would be posting would take me two days or two mornings — an hour or less apiece. I even picked up speed as far as the amount of time I was working on them. I could do it faster and faster, and get more precise. It's interesting how it's an exponential growth of ability.

I feel my brain swelling.

Yeah, you really got good. I was following your story on Facebook and it seems like all of a sudden, you put up that drawing of of Vampirella, and I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ I don’t know how hard you are on your own work, but even you have to acknowledge that the difference is pretty impressive.

Oh no, that's the thing. It's weird because people come up and say, ‘Wow dude, you're drawing really well.’ And I share in their amazement: ‘Yeah, I know, right? These are really fucking good.’ And it's weird. I don't want to seem like I'm egotistical but I'm surprising the hell out of myself with this.

With that Vampirella one, I was sitting at home and just kind of sketching. I drew a different type of line. I had actually been trying to get to a point like that — I guess, like a looser style. It’s been hard to teach myself to get looser when I've been trying to get tighter and tighter for years. And so my left hand had that looseness that I was looking for.

It's just been really weird and awesome to see it happen. The big drawing that blew my mind that I was able to complete it and make it look as good as what I would do with my right hand was the one with two witches brewing up the bongwater soup.

I use a brush pen usually, but I pulled out a nib pen I hadn't used in years and it worked out great. It was like this cool new toy to play with and get different effects.

There's still a difference between your left-hand and right-hand style, though, right? You've gotten better, but you haven't gotten the same.

No, but I'm definitely getting closer, which I'm not sure like.

It's kind of fascinating — I talked to one of my other cartoonist buddies, Kalen Knowles. He said, ‘What if I told you I like these [left-handed drawings] a little bit more than your other stuff?’ And my girlfriend was getting close to saying that to me too.

It's weird to me because I've been working so hard to get a style that I can be comfortable with, and can produce well with my right hand, for so long. And now I'm coming up with this little bit more naïve, or raw, look with my left, and everybody's like, ‘Oh, I like that better.

It also looks more hand drawn. I guess that's what he was saying; it looks like it has a little bit more of a human hand to it.

And I think some people are drawn to that because it looks like something that they'd be able to do. I've had a couple of people say they like stuff that looks not too polished. If it's so polished and super hyper-realistic, they can't even understand it.

But if it looks like someone drew it, and there's mistakes and there's a wiggly line, then people get that. There must be something identifiable about it.

I've been trying to be cautious or kind of aware of how clean and how good my stuff looks, because I don't want it to look like it's made by a computer. I don't like a lot of digital art a lot of times. I see it as soulless. It's too clean, it's too nice.

So if [art drawn with my left hand is] a little rougher, or hand-drawn, or there's a mistake, that's cool. But I don't want my art to be full of mistakes. I look at a piece of my art and I see all my mistakes — I don't see how good it is. And I think that's the hardest thing for artists — liking your style, liking your little quirks, and all the strange things about it. Hopefully, your tastes match up with your audience.

So the cast is off, right?

Yeah, it came off yesterday. Thank God.

Have you been drawing a little bit? Have you had time to readjust to the right hand?

No, I’ve still got to go through some physical therapy. I have a new splint.

But I'm going to have to [get back into drawing with the right hand] because I've got to finish the vampire book I'm working on. I'm interested to see if my right hand has to learn to catch up now. Will I be able to jump back in? Or will my left hand now become the superior hand?

I'm looking forward to using the left hand to sketch out things, or do my rough pencils, because it has that looseness. And then I'll ink it with my right hand so that I can get a tighter look.

So you’re looking to use both hands in the future? Like, at the same time?

I'm not a gecko. I can't spread my eyes and look at two different drawings at the same time. Not yet. I may well try.

Maybe you just need a head injury.

Be kicked in the head by a mule.

Do you think you're going to finish the vampire book by the time Short Run happens on November 4th? Are people going to be able to see your latest stuff at your booth at Short Run?

Oh yeah, for sure. I have only a few pages left on the vampire book. It’s called The Fang and it's about a female vampire who has a job as an assassin of monsters.

I'm also thinking about coming up with a left-handed publication of some sort. Like the closest thing I'm ever going to do to an autobio comic, with photos, probably collages, and some sort of skate art. A photo of my skateboard, and x-rays from my hand, and then all my left-handed art. I think that's something I should definitely do.

I want to see if I can get, at the very least, a coffee shop to host a bunch of left-handed drawings.

Do you have a book out right now that you think is a perfect example of your right-handedness at its apex, before the accident? So that readers can do a before and after comparison?

Oh yeah. The Punch to Kills are the best I've done. And then, The Fang book is definitely the thing that I've been really excited about doing all this year. It definitely is looser than the Punch to Kills, I think, and a little bit more fun.

So, yeah, there should definitely be stuff for sale at Short Run, so you can look at what I did this way and that way. Choose your poison. Pick your hand.

Never trust Aaron Burr and other research tips from a historical romance author

Writing a historical romance novel involves a staggering amount of research. How corsets work, where to throw away that apple core, what kind of naughty words people would use to describe what they’ve done with or to their lovers. We all do the work, but few of us do it as thoroughly as Rose Lerner, whose vivid Lively St. Lemeston books center around the people and events of one small English town. The latest novella in the series, A Taste of Honey comes out September 12th. This interview has been lightly edited.

For the new folks, let's start with a brief introduction to your own romances and particular areas of expertise.

My name is Rose Lerner and I write historical romance, typically set during the English Regency (a flexibly defined time period but I stick to the technical 1811 to 1820). For my current small-town series I've researched politics, high and low, and women's participation therein; queer experiences; the Napoleonic wars; Jewish life; servants; and much more. I also caught Hamilton fever for a while there and devoured books about Hamilton and Burr, and I've got a Jewish Revolutionary War romance coming out in October in an anthology with Courtney Milan and Alyssa Cole.

Do you research before, during, or after you draft?

All of the above. An actor that I love, Nicholas Lea, once said in an interview that he has to make a lot of little decisions in the moment, and research helps him make those decisions. That's how I write. I have a broad idea of the plot when I start a book, but beyond that I pretty much get in character and feel out the story as I go. I research until the POV characters' world feels solid to me. Then I start writing. Sometimes I get stuck and can't continue a scene without information, and then I need to take a research break. Little things, like whether "bear hug" is an anachronism (it is, but I decided to use it anyway) or what the heroine would do with an apple core after she'd eaten the apple (toss it in the fireplace grate, probably), I usually leave a note for myself in the text and research during revisions.

Do you prefer primary or secondary sources, when you have the option?

I read almost entirely secondary sources. Primary sources are great but you have to sift through so much irrelevance! I'd much rather have a trusted middleman pick out the important stuff for me. Of course, how do you know when to trust a middleman? I do like my secondary sources to footnote heavily so I can confirm in the primary source myself if necessary. But can you really even trust a primary source? If it's Aaron Burr, absolutely not. The key, to me, is to read enough that you develop a bullshit meter of your own.

Are there special considerations or pitfalls when you're researching the kind of sex people had in the past?

The pitfall, I guess, is that people talked less openly about the sex they were having in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Which may not even be true! What I can tell you with confidence is that what they DID say was extensively and often irrevocably expurgated, if not by family members immediately after their death then by Victorian descendants. The partial or complete destruction of letters, journals, and memoirs by burning, cutting away, or inking out potentially embarrassing content was common, especially if the writer was queer and/or a woman.

But based on what we do know through erotic novels, pornographic art, and surviving primary sources, it seems like they were having more or less the same kinds of sex we have now: kinky, vanilla, queer, with sex toys, role-playing, using birth control, threesomes, polyamory, whatever. Specificity is important and sexuality is culturally constructed, but at the same time, 98 percent of the time if I hear someone say, “But people didn’t do that back then,” my bullshit meter goes off.

Sure, this masturbation club where new members had to present their dicks on a silver platter does seem a little — quaint. But even there — the details are weird and incomprehensible, but the spirit isn’t that unfamiliar, is it?

How do you approach the language in your sex scenes, considering that historical gap? Writing about queer or kinky sex set before the modern terms were developed, for instance, or the frequent romance-author lament that there are a million period-appropriate terms for the penis and almost none for the clitoris.

Well, I don't see this as much more of a problem for queer or kinky sex than any other kind, because the terminology for ALL sex has shifted enormously. I have finally given up on finding good period terms for oral sex, and if I feel like "pleasuring him with her mouth" is too coy in context, I just use "suck" even though it's first attested in reference to fellatio in 1928.

It’s a delicate balance. A huge part of the appeal of historical romance is a sense of otherness, of distance, of experiencing the world as it might have looked to someone 200 years ago. I try very hard to retain a sense of how my characters THINK, and in particular how they think about sex. I try to think about where they would have gotten their information about sex and what words they would or wouldn’t know or feel comfortable using. I used to hate “pearl” for clitoris and think it was unbearably precious, but I’ve finally given in (although when I’m writing a well-educated hero, I usually just say “clitoris”). Sometimes I’ll even purposely choose an older-sounding or obsolete word when a more modern one is available. For example, “to come” meaning to have an orgasm is attested from 1650, but I frequently opt for “to spend” instead, because I think it gives things a nice period atmosphere.

At the same time, in my opinion TOO much authenticity in a sex scene can be off-putting. I try hard to avoid anachronistic word usage (or at least, distractingly anachronistic word usage, or word usage that represents a shift in conceptualizing something). But about once a book, I give up and use “sex” with its modern meaning of sexual intercourse, simply because in that sentence I tried out “coupling,” “congress,” “bedsport,” “coitus,” etc. and hated the way all of them sounded.

If I wrote “he larked her,” the reader would be confused, and if I wrote “he larked between her breasts,” she’d probably get the point, but she’d laugh. I just don’t see the point of privileging this kind of academic accuracy over storytelling. It’s a sex scene, and it should be sexy.

More about the general vs. specific — how do you balance the broad general statistics ("most people of the time/place would have — ") with the specific examples and the outliers? ("A few exceptional people did — ")?

For something like, "Could my heroine have a front-lacing corset?" this is a pretty simple decision (she could, but probably wouldn't) and in the end, it really doesn't matter either way. I'd probably go with the more likely back-lacing option unless I had a strong story reason to want her corset to unlace in the front (she doesn't have anyone to help her get in or out of it in a particular scene, or I want to realize a specific sexy image).

But this can get pretty political. Whether your character is an outlier or not, you still have to ask yourself, “Why is this the story I am choosing to tell?“ The choice to tell an average story can be just as loaded as the choice to tell an exceptional one, and ”Well, it’s historically accurate“ is never a sufficient justification for anything. I’m sick of hearing, ”They were a product of their time," to justify some atrocious behavior in a historical figure. Literally everyone who has ever lived was or is a product of their time. That’s how time works.

History is not neutral or objective or absolute, any more than memory is. It is the compilation and interpretation of millions of stories. Just because one story has been told more than another, it isn’t necessarily truer. Just because one side of a story has been heard more than the other side, doesn’t make it the “more accurate” side.

An unloaded example: when Aaron Burr, in his old age, tells a friend an anecdote about something that happened between him and Alexander Hamilton fifty years earlier, and then ten years after that the friend writes it down, you shouldn’t take what you’re reading at face value as the truth. (That should be common sense, and yet I see those stories repeated as fact by reputable historians.)

When it comes to history, the same logic applies to basically everything: You have to have common sense. You have to keep an eye out for motivations and agendas, both in yourself and other people, because they’re always there.

You have to be aware of your own agenda. And you have a responsibility to think about whether your agenda hurts people. You have to ask, “Why is this the story that feels true to me?” and then, “Is that a good reason?"

I’ve noticed that my books with queer or Jewish main characters get labeled “anachronistic” in reviews more frequently than my other books, despite my knowing that I put a similar level of care and research into all of them.

Why are so many readers attached to the idea that the average Jewish person in the Regency led a tragic life? And even if you take that as fact (which I don’t), why are they attached to the idea that I should be telling that “average” story when a romance novel is, at heart, a wish-fulfillment fantasy? There were about thirty-one dukes in the UK during the Regency, out of a population of about 15 million (source). Meanwhile, the Jewish population in England in 1800 has been estimated at 15,000. I think my odds of finding real historical examples of young, attractive, happily married Jews are a little better than yours of finding young, attractive, happily married dukes! Yet I’ve never seen a book labeled anachronistic simply because the hero was a duke.

Like a lot of issues in romance, it's an amplification problem. A trope becomes popular and obscures the reality, or mistakes get repeated and then become "common knowledge" in the readership. Historical romance author Miranda Neville recently described the Regency romance as "a long game of telephone starting with [Georgette] Heyer — who is foundational, but also notorious for the classism and anti-Semitism of her books. How do you balance uprooting that negative tradition versus providing something more nourishing to your readers? I guess what I'm asking is how much you see your work opening up a neglected space in the past, versus creating a new tradition for future readers and authors?

I'm not sure I think about it in those terms. Based on my email inbox, I've inspired some other folks to start writing Jewish historical romances, and that makes me happier than just about anything. But I don't write with that in mind. I just write the stories I would want to read.

Genre conventions are there to guide the reader through the story. Following them is part of the bond of trust between writer and reader. I would never write a romance novel without an HEA [Happily Ever After], for example. But when a convention is just plain incorrect (or worse, unjust), then I think I actually owe it my readers NOT to follow it. What matters is not the fact of breaking a genre convention, but whether it’s done in a spirit of love and respect — for the genre, and for the reader.

I’ve read a LOT of Regency romance throughout my life and I have a lot of affection for its conventions, but at this point, if I know Heyer was wrong, I feel very comfortable ignoring her.

This isn’t what you’re asking, but it made me think of it — I once got a rather anti-Semitic review of True Pretenses that suggested, essentially, that in creating a positive portrayal of a Jewish man, I was fighting an uphill battle against the weight of anti-Semitic stereotypes in literature and necessarily closely engaging with those stereotypes as I made character choices. This, to me, is bizarre; it assumes that classic English novels and Georgette Heyer are the only literary traditions there are — and even beyond that, they are the only frame of experience I have to draw on!

In fact, I have not only read and seen many positive portrayals of Jewish men by modern Jewish authors and screenwriters, but I have also KNOWN NICE JEWISH MEN IN MY ACTUAL REAL LIFE. This is also true for plenty of my readers (although not, apparently, that one). While it’s nice to be genre-aware while writing genre fiction, and I absolutely adore playing with tropes like marriages of convenience, fake dating, Cit heiresses, starchy butlers, house parties etc. etc., the Regency romance genre is not the entire context readers are bringing to the table.

If I know something might confuse a reader because it’s not the commonly accepted “truth” of the past, I try to include a little more signposting and explanations. But I’m not going to write beady-eyed moneylenders with greasy sidecurls just because Georgette Heyer did.

If I could summarize all my thoughts about history in one sentence, it’s this: the truth matters.

The truth always matters.

But the past is composed of a million intertwining truths. “People in the Regency could have great sex” and “people in the Regency thought about sex differently than we do” are both true. “Anti-Semitism was rife among Christians in the Regency” and “there was plenty of intermarriage between Jews and Christians in the Regency” are both true. As a author of historical fiction, my job is to decide what the most important truth is at a particular moment.

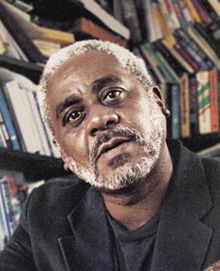

Talking with Daemond Arrindell about poetry, performance, and writing in a community

Our August Poet in Residence, Daemond Arrindell, is having a fantastic year. He co-authored the world premiere of a theatrical adaptation of T. Geronimo Johnson’s novel Welcome to Braggsville at Book-It Repertory Theatre earlier this year to universal acclaim. And he was recently announced as the curator of the 2018 Jack Straw Writers program, which means he’ll select and guide a class of Seattle writers through the process of learning how to perform their writing more effectively. If you’d like to see Arrindell read, he’ll be performing at Sandbox Radio on August 28th, Poetry Bridge in West Seattle next month. This interview has been lightly edited.

First, I wanted to ask you about Your work adapting Welcome to Braggsville for Book-It Theatre. Is the theater something that you've always been interested in?

No. I kind of fell into the world of theater through Freehold. Freehold Theatre reached out to me over ten years ago because of my work in facilitating writing workshops. They have a program called The Engaged Theater Project and it's about bringing theater to culturally underserved populations. There are several different residencies that take place — one at the women's prison down in Purdy and another at the men's prison in Monroe.

The idea is Robin Lynn Smith, who's one of the founders of Freehold, was looking to host workshops at the women's prison to get the women writing about different ideas. She asked me if I could put something together. I put something together. She really liked it. Next thing I know, she has invited me to join the faculty of Freehold, teaching spoken word.

That's how I got into the theater world — by happenstance and by coincidence. And the overlap between spoken word and theater is strong writing, and bringing the craft of writing into life through the art of performance. Most spoken word pieces are essentially monologues — just storytelling in a different format.

Ten-plus years of essentially working in theater but not exactly being a theater artist has opened a lot of doors for me and brought me in touch with a lot of people who recognize that crafting performances in spoken word is very similar to the same skills and tactics used in the realm of theater.

Josh Aaseng, literary manager at Book-It, reached out to me in the spring of 2016, asking me if I would be interested in working with him on the adaptation of Welcome to Braggsville for a couple reasons — one, because of the work that I do in race and equity; and two, because I have experience in the theater and also experience with editing and poetry.

So, within the men's prison I work with a group of guys for a couple months in helping them to write all kinds of styles of poetry and performance. And then I take all of their writing and cut and paste it into one performance that is somewhat theater and somewhat poetry — not exactly either one, but a melding of the two.

That idea of working with writing that is already in existence and cutting and pasting it into something else that is something unto itself — that's very similar to what happens in adapting a book into a play. The experience that I've had actually set me up perfectly for what Josh wanted and needed me to do.

I've been to quite a few Book-It shows, and I think that Braggsville walked off the path of the book a little more than their other adaptations. Was that something that was intended from the very beginning?

It wasn't intended to stray, necessarily. But the question was how do we bring the essence of this story to the stage in a way that people are going to be able to understand it and relate to it, and really take something away from it? Because we're dealing with the issues of race and history, and both of those are very complex issues.

We've got a passionate and powerful story, but it's also being told in a way that's really different and that is not easy to read. When you’re reading a book that's not easy to read you can take your time with it. You can set it down. You can come back to it.

You don't have that [luxury] with a play, so a lot of [the adaptation process] was about how we take these ideas, and these concepts, and this story that's being told, and make it digestible, but while not necessarily making it easy. That was the challenge.

For example, there are these chapters within the book where the narration shifts from he, she, they to you, and it's like the narrator who is not an omniscient narrator shifts into this very intimate interrogation of the specific lead characters. We could have just made those into monologues for the play, but it would have been boring.

Because there's so much being said in a way that is visceral, we needed to be able to make that digestible and also powerful. We needed an audience to be able to take something away from it. Just a one-way monologue wouldn't have worked, and so that essentially is how we ended up creating the character of The Poet.

Yeah, okay. I don't want to give the impression that it strays from the book. I think it works very well with the themes of the book, but Book-It tends to be pretty literal in its adaptations.

Yeah, and from the get-go Josh and I were having conversations about how this is different. The book itself, it feels different than a lot of the things that Book-It had taken on. So, we knew that it was going to be different in a number of different ways.

We could go virtually anywhere from here, but I wanted to ask you about the inclusion of Charleena Lyles’s name into the play — what was the decision to include her like? When did it happen?

Well, we did the same with Philando Castile after the decision regarding his case had come down. The book came out in early 2015 and I felt like, in all honesty, if either one of those people had been murdered at the time that Geronimo had been writing the book, their names would have been included as well.

It wasn't about sensationalism. It felt urgent and necessary because it had just happened, and to remind the audience that what is being talked about isn't distant history, that these are things that are still going on. It felt necessary.

Was there any internal debate then about including them?

I honestly don't remember whether it was Josh's idea or mine. It may have even been a cast member's idea. We talked about it for a couple minutes, Josh and I, and there wasn't any debate. Again, the idea behind the play in itself is to make what's going on in this book real.

Live people talking about these issues in front of someone makes them more real, makes it more urgent. And I don't think there's anything more urgent in regards to these issues than someone having been murdered within a few days or within a few months of the play itself.

It kind of felt like in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen where she keeps updating the book in new editions with the names of Black people who have been killed. It was incredibly powerful. It's been a year then since you adapted Braggsville, more or less. Has that affected your work at all? Has that adaptation done anything to your writing, do you think?

That's really hard for me to say. I feel like I haven't had enough time to bet that perspective yet, mainly because it still feels present. But the realm of theater feels more open to me; I can say that.

The idea of one-person shows feels more accessible to me. The idea of writing for theater feels more accessible. But yeah, I don't know whether it's changed my writing yet other than the fact that it definitely lit a fire under me and the world seems even more open and accessible.

I know that this question always comes up, but I think it comes up because people are interested: Can you talk about the relationship between spoken word in your writing and in writing the poems on the page?

There isn't much, if any, difference to me. I personally believe that a story of any kind, regardless of the form, isn't finished until it's shared aloud. So almost everything that I write I'm intending to have read aloud at some point; I feel like that's part of its journey for me.

There are some poems that almost feel like they're meant to live on the page more than read aloud, but that usually comes after the writing and I'm looking back at it as opposed to while I'm writing it.

I tend to do more editing for the page or for the stage as opposed to writing for the page or for the stage.

It was just announced last week that you are curating the 2018 Jack Straw Writer's Program.

Yeah. I was a 2013 Jack Straw writer, but it feels like yesterday. I loved the experience. I loved my cohort, and Stephanie Kallos was our curator. She was definitely influential in regards to my writing.

I've always been a fan of Jack Straw's work — the oral storytelling aspect of taking stories in any form and getting them heard, getting them into other people's ears. Not just getting these stories written and existing on the page, but getting them to a place where they can be heard by others.

I definitely feel more comfortable with how to bring the performance aspect out of something than how to write something. That's my own insecurity and my own work that I still have to do as a writer as I'm continuing to grow, and as I continue to work within the realm of publishing, within the realm of the page itself.

When it comes to performance, bringing something that's written to life, I feel more than capable in assisting other writers — writers who are very well established on the page — helping them to figure out, how can I take this thing that is static on the page and make it into a living, breathing form of art?

Okay. Is there anything you're looking for in particular in these people who you're choosing for the program?

Not as of yet. This just happened a couple of weeks ago, so I haven't gotten that far yet. I think in general I'm looking for stories of any kind that really move me. I have a feeling that the stories, poems, etc., that are taking the political and making it personal, or taking the personal and making it political. Those stories in general tend to move me. Those stories are definitely going to catch my eye, but I definitely don't have a requirement or a recipe at this point for what I am looking for.

When you were talking about your writing being the thing that you were most insecure about — I don't know if insecure is the right word. I don't want to put words in your mouth…

No, definitely.

Is that something that you are going to be focusing on personally as you move forward?

I continue to work on that, and that's where classes and writing fellowships come in handy. For me, I've found a lot of it comes to making the time for it. When I'm just focusing on my writing craft I tend to feel more secure with it. When I make the time just to focus on my craft as opposed to ‘I'm just going to pump out this poem,” I feel more secure with it.

Those are things that I'm consistently working on doing: some of it is setting aside the time and some of it is making time to read writers who are moving me, get exposed to new writers. Some of it is taking classes and workshops to continue to add to my toolbox, and some of it is making the time to just focus on the craft.

All right, so who are the writers who have been moving you lately?

Right now, Warsan Shire is one. She blew upsemi-recently as the poet behind a fair amount of the writing from Beyonce's Lemonade. I found out about her a couple years before that. She was at AWP when it was here in Seattle.

Ladan Osman is another one who I've been blown away by. I continue to be in awe of the two of them.

Other writers who are influencing me right now: T. Geronimo Johnson, Natalie Diaz, Ta Nehisi Coates, Douglas Kearney, Jamaal May, Patrick Rosal

It seems like you are very involved in the community, obviously, with your work with prisoners, and working with Jack Straw, and things. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your evolution as a citizen of poetry. Is this something that has always been important or do you feel as your stature has elevated in the community your commitment has grown as well?

I feel like I've always had it. It's just that the lens of how I'm helping has changed. I started out as working in social services, so I've always been a listener. I was a counselor for a long time, and it just slowly came about that as I was listening to people's stories and I was continuing to write my own, the opportunities to help people tell their stories in different ways started to present themselves.

Whether it was facilitating a workshop around writing, whether it was leading a workshop regarding youth empowerment, it still is helping people to tell their stories and being a witness to those stories. There's a saying, and I don't remember where it comes from, but listening is a transformative act. I, by listening, am changed, and so helping people to be able to tell their stories, it empowers me, and it changes me, and it helps me to grow.

Why Jen Vaughn is joining forces with comics superstars like Neil Gaiman and Gerard Way to raise money for Planned Parenthood

Last week, the founders of the website Comics Mix launched a Kickstarter for an anthology titled MINE!: A Comics Collection to Benefit Planned Parenthood. The anthology is star-studded, featuring writers like Neil Gaiman and Gerard Way and artists including Becky Cloonan and Jamaica Dyer. The project must reach $50,000 by September 15th to be published, though it’s already off to a great start. We talked with Seattle-area cartooning/inking/writing powerhouse Jen Vaughn about how she got involved with the project and why she’s such a passionate Planned Parenthood advocate.

Could you explain in your own words what Mine! is?

It’s a comics anthology featuring some of the best and brightest and then me. These stories turn their focus on a woman's right to her own body, the decisions she makes with it and the continuing struggle for women, especially women of color, to hold their agency. The title is derived from that ideology — it's MINE, so keep your fucking hands off it.

There are a lot of big names in this anthology. Are there any creators you're especially excited to share a pair of covers with?

Gabby Rivera, of Juliet Takes a Breath and America (the comic); Cecil Castelucci who writes Shade the Changing Girl — I just met her, she's fantastic. Tee Franklin is another writer who I'm excited about. She Kickstarted her new comic Bingo Love, and I'm ready to put my eyes on that book. Maia Kobabe and I traded comics at San Diego Comicon, they wrote and drew this moving comic on recognizing fascism through memory and books. I'm very ready to see their collaboration for Mine! And of course, Sarah Winifred Searle — I've always admired her work. We were both tabling at MeCAF (Maine Comic Arts Festival) in Portland, Maine back in, oh geez, 2011? It feels like we've been doing a lot of growing and drawing alongside each other, miles away and pages apart, so I'm pumped to be in another book with her.

You're a really busy freelancer. Why did you choose to get involved with this particular project? What does Planned Parenthood mean to you?

It's excellent that my facade of being busy is working! The timing was right when editor and organizer Joe Corallo contacted me, and I've had this story kicking around for awhile. Planned Parenthood has done a lot for me over the last 15 years.

I spent some formative high school and college years in Texas, and it's a very hostile place. There was a student group, VOX/Voices for Choice, I volunteered with at the University of Texas. We basically passed out free condoms, dental dams, taught people how to use them (to undo some of that religious health class BS about it being easier to not use condoms), and how to contact your Senators and Reps about Plan B.

Because we were in Austin, we occasionally went to committee meetings or public forums for healthcare. The reps on the healthcare boards would usually be five “old gray-faced white dudes with two dollar haircuts” and one young Catholic Latinx man. It was infuriating. It IS infuriating. I made a lot of bad college art about sexuality back then.

Also, because my mom's an intense baker, I had access to candy molds so I made LOTS of penis, vagina and birth control pill chocolates with all sales going to our college group and Planned Parenthood. If I didn't know people were racist by then, I certainly did when people only wanted to buy white guy penis chocolates — like anyone likes the taste of white chocolate.

I'm writing and drawing a bit of a fantasy piece so I'm not ruining any plot points by telling you Planned Parenthood was there for me during my abortion. I'd spent a year volunteering with Lillith Fund, a helpline which supported women emotionally and helped come up with ideas to crowdfund their clandestine abortions. It was wild, what could a 20 year old do to help a 35 year old desparate not to have yet another child, but their husband wouldn't use condoms or birth control.

Planned Parenthood has also been there for me every year when I go my engine checked out — so affordable compared to other places — and including this year when terrifyingly, I found a lump in my breast. (I'm fine, for now, though we're all moving closer to death).

Do you think artists have a responsibility to be political citizens? Do you think Trump changed that dynamic for you?

Artists cannot help but be political citizens, although it depends on the type of art, honestly. My idea behind every new project is to try something new — sometimes it’s art-related, sometimes it's writing-related. Part of my new goals, probably since moving to Seattle, have been to help lift up other people's voices, especially women of color — not that I'm monied or famous or in any position of power. This means drawing other people's stories or collaborating, not just owning the entire project, because it's a reflection of our society.

When I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, it seems like comics tried to be apolitical. On the one side, you had corporate comics, which didn't stand up for anything, really. And on the alternative side, you had cartoonists like Dan Clowes and Chris Ware who didn't seem to be particularly political. (Of course there were cartoonists like Roberta Gregory who were fearless in portraying abortion as a reality, but even her comics seemed to walk up to a line and then stop, politically speaking.) Is that changing? Are American comics developing a social consciousness? Or do you disagree with my reading?

Hmm. I think there's a difference between gag comics/political comics that emotionally resonate immediately versus a graphic novel that can manipulate character development and create compassion within the reader.

Being political now in comics isn't necessarily writing about politics, but being more inclusive with the dynamics of everyone creating them. It's like editor Joe Hughes bringing in writer Nnedi Okorafor to Vertigo a few years back; it's Gene Luen Yang building an empire with First Second from American Born Chinese to Secret Coders AND encouraging kids to a summer reading program with Reading Without Walls bookmarks (they were VERY realistic in suggesting 3 books since not all kids loved the library as much as say, I did). It's Hope Nicholson creating The Secret Loves of Geek Girls book and the soon-to-be-released follow up at Dark Horse, The Secret Loves of Geeks, that includes all genders and genderqueer people. It's the company Black Mask printing a series written by a trans writer, Magdalene Visaggio, with trans characters, drawn by Mexico-based Eva Cabrera (if you haven't read Kim + Kim by now, just GO — get yourself to the bookstore or library).

But with that being said, the 'slow death' of newspapers, and especially staff cartoonists, has left a gap in the world — one that is being met online by many cartoonists, especially Matt Bors at The Nib, with Nomi Kane, Pia Guerra, Joey Allson Sayers, Maia Kobabe and more. The political cartoons once clipped and taped above the breakroom coffee pot or to the door of the bathroom are now shared via social media. It's amazing how technology changes and we still see the same behaviors. (I just said that with my best Neil deGrasse Tyson voice)

What else are you working on? How can our readers keep up with you?

I'm finishing up some SECRET comics and covers that should be announced soon. But you can still pre-order my other current Kickstarter project, Haunted Tales of Gothic Love, edited by Hope Nicholson. Mel Gillman wrote a delicious queer love story featuring gold miners and a ghost; it's been quite fun to draw and I'm very sure it will haunt readers.

I'm working on multiple projects with writer, Kat Kruger, including just turning in that application for the Georgetown Steam Plant graphic novel project!

Locals can see me at the Red Pencil Conference on September 23rd. I'll be tabling with Kat Kruger and on an editing panel with Kristy Valenti of Fantagraphics and mainstream artist Moritat. And in March of 2018, I'll be tabling at Emerald City Comicon!

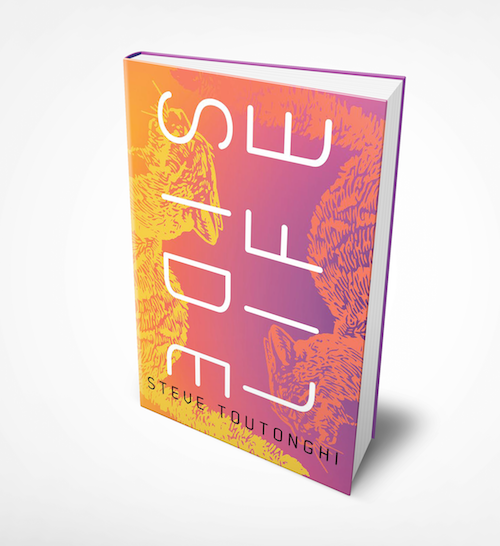

Talking with Steve Toutonghi about all the work a book cover has to do

Next May, Seattle author Steve Toutonghi is publishing his second novel, Side Life, with Soho Press. Today, Toutonghi and Soho are exclusively sharing the book's cover with Seattle Review of Books readers. (That's it right up above this paragraph.) The novel — about a discouraged internet entrepreneur who takes a demeaning job as a housesitter in a billionaire's tech-haunted mansion — has to convey a lot of information in its cover: it has to look futuristic but not too distant, it has to convey the sense that it's a thriller, and it has to stand out from all the rest of the books that will be coming out next year. I talked with Toutonghi about the process of creating and choosing a cover for a book, and what kind of work he thinks a successful cover has to do. This interview has been lightly edited.

Our readers are very interested in the relationship between writers and the covers of their books. I think people tend to believe that authors have a lot of control over that process, but most of them don't. Tell us what the process was like for you. This is your second book, and it’s your second with Soho Press, right?

Yeah. I'll start with the last book, because I think it may have influenced how things went with this one. I really didn't have much of an idea of what to expect that first time. I received a proof of the cover and I loved it, and I wrote back to Soho that I loved it, and that was pretty much my degree of involvement in the cover design, which was fine with me.

With this one, when I received the cover file I thought it was just an incredibly smart interpretation of the content. I had some conversations with booksellers about the function of the cover in different contexts, and so I had a question I wanted to raise with the publisher, and I said, "What about this thing that I heard might be a concern for booksellers?" And then they took my concern into consideration.

And a couple weeks later they sent the new proof of the cover — it was same concept, but I had asked a question about the colors that were used, and they adjusted the color. So all in all, it was a very positive experience. Certainly, they listened to me, and they took it into account. But they, you know, started the design process and sort of walked through the initial context and all that stuff without me, I didn't have visibility into that. The things that I did get were really polished, professional, very smart takes on the content of the book.

So I was happy with the process, but I didn't have a lot of sort of early input into it, which was actually probably the right thing to do because they know what they're doing. Covers are really complex — they're doing a ton of work. The designers who work on them have worked on a lot of projects, and the people at my publishing house do a fantastic job. I'm more than happy to have the kind of experience that I had with them. It felt like a very, very much the right degree of influence for me.

Yeah, writers are not necessarily great at visual communication. Often I think what a writer senses a good cover might be is a little bit distorted. Are there any covers of books that are not your own that you really enjoy? And, conversely, are any covers that have always bugged you as a reader?

Honestly, you know, there's this whole kind of line of covers that are using conventions of genre. To me, they’re covers that seem cheesy or not all that interesting. But in a lot of cases the people building those covers are talking with an audience that I'm not really used to communicating with, so I don't know really what they're doing. I feel a little reluctant to pass judgment on them. I'll look at a cover and think, "well, I'm not super-excited about that," but that doesn't necessarily mean the designer didn't hit their marks or do the thing that they were trying to do.

Right, there's a common language in genre covers that fans understand. Your publisher Soho is in the mystery space, but their books don't look like the covers of a lot of mysteries and thrillers that are out there, right? Their books certainly don't look like the sort of thing that you think of when you think of Sue Grafton or, you know, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Yeah, I agree. I don't know if you've seen their Soho color map? They have a poster that they printed in 2016 where they had their mystery authors aligned by color. The point of the poster was showing that they had this large library of very high-quality mystery writers and their design process had resulted in enough similarity to show them as a library with a coherent visual identity. One of the ways that they're doing a really incredible job is through their focus on high-quality design and doing things right.

There’s a book that's coming out from Soho shortly, Sip by Brian Allen Carr. I think that's a beautiful cover. I love the way that the title is sort of partially obscured by the smoke, and I think it's very elegant and also a little threatening. Also if you read the synopsis it seems appropriate for the content. I haven't read the book, but -

[Reading the synopsis] “…the highly regimented life of those inside dome cities who are protected from natural light…,” OK. That makes sense.

And people drinking their shadows.

Yeah. That looks very appropriate, and in the hands of another publisher, I bet it would be more genre-y. Not that there is anything wrong with that.

Yeah, and I think if you want to go into action, they also have Robert Rapino's books. Those books have, I think, a really striking visual identity that's really clear and that speaks, I think to sort of the precision of the concept. The animals get smart and attack the humans and fight with each other. The covers really speak to the big-concept clarity of the world he's creating.

They're very sort of cool and futuristic.

Yeah, but isn't it interesting how it can be cool and futuristic, and also just a cat's face?

Yeah.

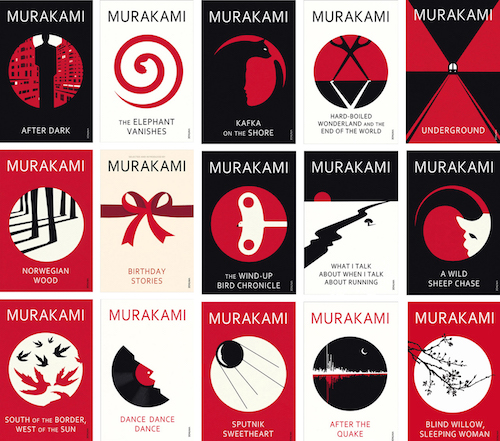

I like that. I love that. And then diverging from Soho, there's a lot of really cool things happening from Viking books. What they did with the redesign of the Murakami books — I think those are really cool.

They fit altogether in sort of a unified graphic, which is crazy, and the elements kinda spill off one cover and onto another.

I hadn't seen them like this all laid out together like that. Yeah, that’s kind of a dream for an author, right?

I think so.

When I started reading novels, there were the Vonnegut covers with the giant "V." They don't really have much of a graphical element on them, but that's how I read through Vonnegut. I would look for those books and find them and read them based on their covers.

That’s an interesting example, because I know exactly what you're talking about. My mind immediately calls up an image of them.

So bringing it back to your cover for a bit, you said you got some advice from a bookseller on the new cover. Can you talk a little bit about what the bookseller's input was?

I'm just going to talk generally about conversations I've had with booksellers about covers, and not specifically about the covers of my books. So, for example, I'm used to going to a bookstore and I'll see a cover — the spine of a cover, or the cover's facing on a shelf. Booksellers talked a lot about the cover existing on a table in the context of a bunch of other books, which was something I hadn't really thought very much about. And you know, the facing cover on a shelf is in a different context because it's likely to have spines on either side of it. And then, you know the spine is another context. But on the table, you want a cover that's going to pop a little bit, that's going to suggest that a person browsing the books on the table pause and pay attention. You want something that won't wash out.

One of the booksellers talked a lot about how he liked the covers to have some kind of internal color tension, so that it didn't rely on tension being established by books next to it. Because colors in the publishing industry sometimes move cyclically. So, a certain pallette becomes widely used, and then there's sort of a movement to another pallette.

Oh yeah, that's totally true. I think last year at this time bright yellow was in vogue — you would just go into a bookstore and there would happen to be like five bright yellow books on the front table at a bookstore. And it's not coordinated, obviously. Nobody wants their book to look like everyone else’s, but it's just one of those weird things that happens with fashion and design where people follow trends without even realizing it.

Yes, and so he was saying, “look, you're going to run the risk of that happening. So try and create some contrast on your cover, so that if you get into that situation you don't lose the browser's eye as they pass across the cover. I thought that was interesting.

It seems like there a lot of conversation about the degree of legibility — there's a tension between the legibility of the text and the freedom of graphic design that the designer feels that they can explore as a way to express the emotional content and emotional relationship with the book. I think that's really interesting — how the designer approaches the idea of legibility versus the emotional design.

Can you talk about where you think the cover of your new book resonates with the story?

The story has a note of urgency, but it is also set in a very familiar context. And so they did this really wonderful thing with the colors. The colors are kind of bright and they pop and the title is two really simple words, but they’re arranged in such a way that there's this nice tension. So I feel they did a really good job of connecting the design and the content of the story.

And then there's cats, which provide familiar context and are potentially comforting. But the cat in the story has a really specific role, and I think it's nicely reflected in the way that the cat appears on the cover.

I'm sort of at the edge of my seat to see what will this look like in the context of a table at a store.

Another thing that I like about that cover is the text is sort of large and bold, but also part of the overall composition in a nice way. So the cat and the colors become kinda abstract as you shrink down to Goodreads size. For me, I feel like it's successful at communicating that sense of tension and familiarity at the various sizes you’ll see the cover in. It's important to do that.

That hadn't even occurred to me: the different ways covers are presented these days. You've got to communicate the book’s contents on a table with a bunch of other objects. You have to communicate it as something that belongs on somebody's shelf at home, but you also have this postage stamp size that's got to grab people's attention on social media. That's a lot of levels.

It really is. There's so much going on. There are so many moving parts that as an author, it’s really useful to me to feel comfortable that I have people who are experts, who have experience, and who have a track record advocating for their concerns in the design process.

It's like this crazy, very complicated moving target, and it's amazing how many beautiful covers are out there, given all those constraints.

"We really are one of the top literary cities of the world." What to expect from this year's Seattle Urban Book Expo.

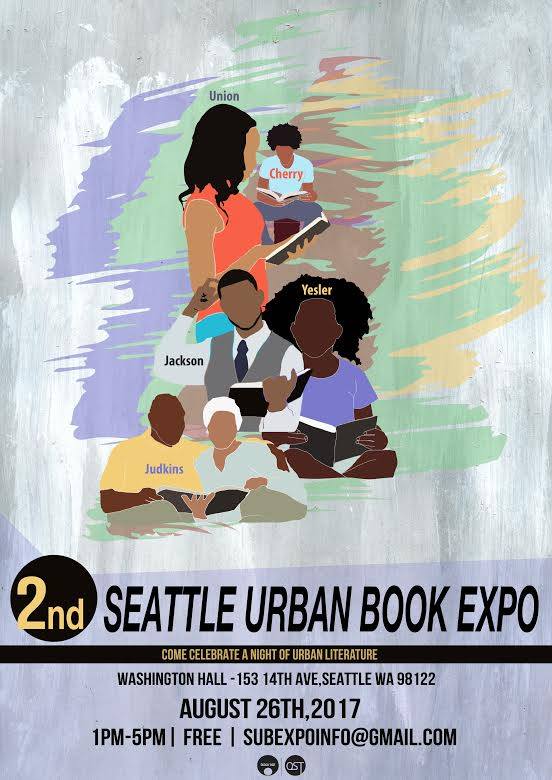

This morning, we interviewed J.L. Cheatham II about how he decided to be an author. The second half of this interview covers how he decided to launch the Seattle Urban Book Expo, and explains what people can expect from the second Seattle Urban Book Expo, which takes place on August 26th at Washington Hall.

So you just decided to throw a book expo without having any idea how to do that kind of thing.

It was kind of like an “if you build it, they will come” thing. So I connected with some people and got the space, and got everything going.

It turned out it was way more successful than I ever imagined. We had a total of eight authors including myself, a total of 250 people showed up to a space whose max capacity is 100. So there was this constant flow of activity. Everybody was having a good time with books, and I was like, "oh okay. We really are one of the top literary cities of the world. All right, cool."

Then the feedback afterwards was so humbling because everybody was like, “when's the next one?”

And now you’re having another one, on August 26th. Is it in the same spot?

No, it's at Washington Hall. It's from 1 to 5 pm. It's gonna be a party. That's the goal, I want a literary party.

Washington Hall is a great venue.

I love it. The staff is so…I feel like they're family now. I literally just pop up on them. I won't even announce myself, I just go over, knock on the door, they open the door for me, I'll just chill out, drink coffee, play dominoes, whatever. They've been great to me, everybody involved.

So, what can people expect this time?

Like I said, the goal is to have a literary party.

We've got 20 authors, we're gonna have four food vendors so people will have plenty to eat.

One of the things I noticed at the last one was people brought their kids, and I had nothing for kids. So this year I'm gonna have something called Juice and Paint, where there's a room in Washington Hall where kids go in and color, draw, write stories, and paint as the adults circulate the room and buy books and stuff like that.

Also, I have a face-painter too —that's gonna be outside near the food court. Well, I'm calling it the food court. It's really the parking lot, but I'm gonna turn it into an outdoor food court.

We’re gonna have music. I'm trying to keep people there. I want people to show up and stay for a bit. Nothing really starts a conversation than what type of literature you're into — especially when there's food and drinks involved. So that's the goal. Everybody can have a good time.

How did you get more than double the authors in two years? Did they come to you, or did you reach out to them?

I’m very heavy on social media. I promote everything all the time. Everybody was recommending this one because I think people remember [last year’s expo]. I was posting videos and pictures ot it and really highlighting how good of a time it was.

So I think people don't want to miss out on this one, because most likely, I'm only going to do this once a year. If you miss this one, you got to wait a whole other year for the next one to come.

Who are some of the writers that you think our readers should keep an eye out for this time? I know you love them all.

I love them all, but if I have to be selective, NyRee Ausler. She's doing a series called Retribution. I call it a romantic thriller. It really grabbed you from the first chapter.

Okay.

Also, Sharon Blake. I love her stories. She has a book called The Thought Detox. She has a very troubled past and she overcame it.

Who else? Key Porter does her comic book series called Shifters. Another author who I'm interested in meeting for the first time is Omari Amili. I love his background. I just love stories by people who triumph over hard times and they don't let their situations define them, you know what I mean?

And you’re doing an event at the library just before this?

Yep. So the week of the Expo, August 23rd, we're having an author Q&A at the Seattle Public Library, the central branch in downtown Seattle. I'm going to be hosting and we're going to have three authors show up, NyRee Ausler, Zachary Driver, and also a representative for Seattle Escribe named Kenneth Martinez.

We're pretty much going to open ourselves up for questions for people who are in attendance. This is really like an open house for people to know what the Seattle Book Expo is.

I feel like this is my coming-out party. A lot of people know like we're trying to create an institution, and to create a culture of cultivating these promising authors here who feel like they don't have an outlet to express themselves.

We also have another Q&A event with the King County Library at Renton Library. That's on the 25th, at 3:00 pm. We have five authors that are going to be there: Freddy McClain, Key Porter, Raseedah Roberson, Omari Amili, and Natasha Rivers. It will be kind of the same structure: talking about their experiences as writers, reading a few passages from their books. I want to give the opportunity for people to get to know the authors because on the day of the expo, it will be pleasant madness.

I love that, “pleasant madness.” Did the first expo work for you? Do you feel like you're getting your work out there now?

Yeah, I really do. After the expo, all this stuff started happening. The book signings in Barnes and Noble, the work I do with Amazon, all this other stuff. Also, one thing that's weird, but pleasantly weird, is that people are calling me and asking me questions like I'm some kind of expert, seeking my advice.

You mean like publishing questions?