Archives of Seattle writing prompts

Seattle Writing Prompts: The mystery Coke machine

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

Look, let's just state it right out: there may be haunted pop machines in the world, but this ain't one of them. No, instead there is some very real person who stocks this machine, and has for years. Why? Probably because people keep buying sodas. Then one day, a dust devil of mystery poofs up around the machine — legends grown in a cloud of pot smoke and a desire to make the world more magical than pedesterian — and now whoever that restocker is has practically become the Seattle version of the masked man who leaves flowers and cognac on Poe's grave.

That machine was always kind of weird. Have you noticed that most pop machines (and, I use the term advisably, since we score high on the regional soda v. pop issue) are inside? Or, if not inside, at least under shelter. Rare is the machine just left to the elements, sitting on the street like a discarded fridge. That somebody plugged in. And stocked. That you keep buying food from.

It's also been a fixture of Capitol Hill for many, many years. I can't remember a time it hasn't been there, and I've lived in Seattle since 1987. Have I ever used it? Not that I can recall, but, although I'm sure the product is just fine and safe to drink, it always felt a bit out-of-place to me. I like a little more provenance with my drinks.

I love to think of the people who use it, though. Who use it, or might want a quick drink and happen to have three quarters jangling around in their pockets. How many bought sodas there and then walked up Broadway to Bailey/Coy? How many stopped off on their way home from concerts, or before grabbing a burger at Dick's, or before meeting their dealer?

So many stories, and we only have time to prompt five of them:

Today's prompts

The batcavers — The black lipstick felt weird, but the spiked hair and leather pants felt great. When he almost broke his ankle on those fucking platforms, he stopped and leaned against the Coke machine to fix a strap. "We're going to be late, Gerald" she said to him, taking an aggrevated drag on a clove. "Fuck off, Miranda," he said, and then looking up at the machine. "And give me some quarters." She rolled her eyes in disgust. "You're so fucking pedestrian," but she started digging through her purse, and her black-painted long nails came out with three shiny quarters.

The serum — At first, the professor thought about putting the serum in the water supply. But then, if everybody changed overnight, surely an outcry would raise, they'd figure it out, the way everybody would cluster around certain resevoirs. So he came up with the idea of a soda machine selling cheap pop. He'd make money, and the pattern of infection would be much more random and hard to trace. Less broad, yes, but much more interesting. Much more nefarious. Now then, where to place this machine....

The lovers — "Do you have a Coca-Cola?" his date asked, laying next to him in bed, their skin glistening with sweat. "There's a machine on the street, downstairs." That caused a laugh. "Do I look like I'm gonna go down to the street for a pop?" A shrug. "Maybe. Maybe I'll dare you to do it naked. I'll give you my keys and you run down their naked and get us a couple of cans of Coke, and maybe then I'll feel recovered enough to do you again when you get back." His date laughed. But then, stopping, said, "You're serious, aren't you?" He smiled. "I don't know. I guess it depends if you're brave enough. Are you?"

The slot machine — It's been said that every 10,000 cans or so, the spirit appears. Some might say genie, but that's got a certain set of expectations. No, this spirit is more subtle. It does grant wishes, but you don't have to ask for them specifically. You just need to wish them, and so this is why people tell you to think good thoughts: if you put your coins in the machine, and pop open the drink, and take a sip of the cold soda, the first three things you wish for are coming true. You better hope they're not the kind of wishes that will haunt you.

The stocker — There's a story behind the machine and how it started. There's a story behind the couple who keep it stocked. The story has many elements, but the three most important are: a bet on a horse, an airplane that almost crashed because of a watch, and running into an old friend on a very cold night.

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Capitol Hill Radio Antennas

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

Oh, those blinking sentinels. I guess I could have written this about the towers on top of Queen Anne, but there's something about the way these three sisters are clustered together atop Capitol Hill, just off Madison, straddling 17th, two on the West, one to the East.

The three towers belong to: Q13 (or rather, it's parent company Tribune Broadcasting), KCTS, and a company called American Tower that specializes in radio and communication towers. They are, all three, about 410 feet tall, and the ground they sit on is some 560 feet above sea level, so next time you walk all the way up Madison from downtown, you can make sure your Fitbit is counting those stair flights correctly.

There's something so evocative about towers. One time, I drove across the University Bridge, southbound, on a nice Fall morning. I failed to look up at the electrical towers that stand next to the bridge, impossibly tall, because traffic was bad enough, or I was focused enough on my destination.

What I missed by looking up was a trans woman named Ara Tripp who had climbed one of those towers to the top, stripped topless, and spit fire into the morning air as a way to protest the fact that men could walk around topless but women couldn't.

Sadder stories have happened on these towers — suicides and accidents, but a tower always gives a promise. A promise of being able to climb and gain a vista, of a blinking light that might extinguish and cause a plane to immediately impale itself, of surging watts of transmission power, sending media wirelessly to radios and televisions that can receive it.

In Seattle, we have so many of these tall towers because our electronic transmissions need to penetrate the valleys and hills, to get signal to the highest amount of people. As anybody living on the base of Queen Anne or Capitol Hills knows, the landscape throws a shadow of ill reception to those at the bottom who must rely on cable or suffer with poor picture.

But let's think of these a bit more magically, yes? For today's prompts, lets try to unlock something bigger and more fantastical.

Today's prompts

The pattern was unmistakable. The Earth people, with these three towers, were clearly signaling. It took a year of their time for the full cycle to emerge, and at first it seemed almost random. But after parking a ship disguised as one of the primitive Earth satellites to observe, they were quite sure there was no way this could be accidental. So now, finally, they were ready to deliver exactly what the Earth people had so clearly asked for, exactly as they asked for it. They only hoped Earth people truly understood their ask.

It was on. The course was to circle each tower on Queen Anne, then over to Capitol Hill to circle all three, and back to land on the roof deck in Lake Union before anybody could track where the bladedrones were coming from. Fastest racer took the pot, and with twenty entrants, the pot was pretty damn big. It wasn't technically illegal to do this, but only because these specific types of drones hadn't been outlawed yet. They were pushing them to the limits of their range, but surely, nothing would go wrong, would it?

The big house under the towers was always dark. She had blotted out the windows. She had stapled chicken wire to every surface, and grounded it to a pole she dug through the concrete foundation and earthed to pull the signals out of the air. But still, the signals came. She couldn't leave the house, not that she hadn't tried. And she couldn't blot out the signals. It wasn't until she started meditating, being still, and letting the painful signals course her body that she finally understood what they were trying to tell her.

And so through the destroyed city the couple went, down to their last few cans of food. Watching for the rauben, the cloth wrapped reapers. It was the towers you wanted, so the friendlies had said. The towers had platforms built between them, and on those platforms were the traders. And if the traders liked you, and gave you work, you could live a decent life. Sometimes, they said, the towers vibrated like they were still full of signal. Sometimes, they said, it almost seemed like before the fall had begun.

The blinking lights had always been so comforting to him. He'd hunker down, right up to the cold window in his little closet room, the chair under the door so maybe they couldn't come in. They'd be fighting in the other room, throwing words and smashing things, yelling and blaming and cursing, all drunk and high and whatever, and he would just watch the red light turn on, and off, and on, and off. How could anything be so steady in such an uncertain world? So it went until the one night that was more horrible than all the last, and he found himself floating up to those lights, sitting on top of one, the flashing beam painting his little legs. He had to be dead, right? He had to be a ghost. And now he had a ghost job, up there, to sit on the tower and make sure the world was okay. To stop the world from making more ghosts like him. Maybe he could save every child.

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Seattle Center Monorail

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

In the many years I've lived in Seattle, I've heard a myriod of complaints about the Monorail. It's a toy, people say. Too short. Goes from nowhere to nowhere. Is too old. Is too slow. Isn't the future we were promised.

Built for the Seattle World's Fair in 1962, the one-mile track starts near the Armory, curves through MoPop (sometimes rebrands are eye-rolling, but this one makes so much sense) before heading up 5th Avenue.

The ride is short, only two minutes or so, with a top speed of 45 miles per hour. There are two tracks, and two trains, but unless a major event is happening at the Center only one operates at a time. But you knew all this already, right? There is not much mystery about this tiny transit system, this boutique teacup of a train. It's like a proof-of-concept that never got the green light to go beyond its diminutive domain.

The Monorail has enjoyed fifty-plus years of being a Seattle icon, an avatar on the flag we like to wave. Elvis rode it, after all. It's part of our self-image, or consciousness, and our extended identity.

It's a safe ride — mostly. There was a two-train collision at a choke point at Westlake station once, and after the price to fix a door was quoted at outrageous numbers, the Seattle Opera Scene Shop (which is sadly being closed, displacing some of the greatest artists and craftspeople in our region) came in and manufactured new doors for a fraction of the price. A fire in a electrical system led to a Seattle Fire Department evacuation of a train via ladder. It is a safe ride (nobody has died riding it, to my knowledge), but something about it feels a bit unsafe, as if the car might just list off the rails and slump to the ground. Maybe that's why expansion never happened.

Not that people didn't try. They say the original line was supposed to be be an extended region-wide system, to the airport and beyond. but it wasn't until 1997 that a grassroots effort to expand the Monorail made it to the ballot. Over the years, four votes to fund the initiative and spin up a new transit authority were passed, until a fifth vote dismantled the whole system in 2005. The plan was scuttled by bad management, internal politics, external politics, bad public perception, and the utter disbelief from City Hall that the people could actually mandate the kind of regional transport system they want without being told what they want.

That this plan didn't work ultimately is less painful with the furthering expansion of Sound Transit's wonderful subway system. But it's still fun to think that if the Green Line had been built on time — and, that's a pretty big 'if' to swallow, given the way their agency was run — it would have been twenty-six years old when the Sound Transit line to Ballard opens in 2035.

Maybe the whole thing was a pipe dream to begin, but wasn't that the promise of the original monorail? A little dreamy future in the middle of this town with an identity crises about being taken seriously. But then again, maybe we should have stopped with our plans when they were pre-parodied by a Simpon's episode. It might have saved us some heartache.

But for those of us that love the Monorail — I ride at least once a month or so — there will always be a bit of dream that I could ride all day, along the elevated tracks, through the city, watching the sun sink below the Olympics as I'm taking the train home.

Today's prompts

Action movie — The call came at 10:39 am, echoing over the loudspeaker at the fire station. A truck carrying explosive charges for the Space Needle New Years' celebration just crashed into one of the Monorail support posts causing a huge explosion. The support collapsed just before the train approached, and now a car full of tourists was dangling over Fifth Avenue....

Meet-cute — It was love at first site, at the World's Fair, and it was a two-way street. Time stopped when they saw each other. Holding their breaths, neither could look away. But one was on the Monorail train about to exit, and the other was on the platform about to board. They saw each other through the glass, the shuffling crowd of the World's Fair pushing and commanding them onward. But there was no way to let an opportunity like this past. Drastic action must be taken.

Musical — The players: the young woman who just lost her husband to cancer. The homeless man, a skilled musician, whose personal battles overrode his talent. The precocious twins with perfect pitch and a tap-dance routine. The off-duty cop with a heart of gold on her way to see her sweetheart. The dandy with the pocket square and waxed moustache. The drummer from the streets who plays buckets for change. The setting: a one minute monorail ride, and when the doors open, the rest of the world.

Horror film — The drivers all talked about it. That feeling when you crossed Denny, that feeling of a hand suddenly grasping your ankle. Of pulling you, like it wanted you under the train, on the track, in the wheels. And that one driver who swore, after feeling that creepy sensation (five drivers had quit because of it), that she saw a young girl in a pretty dress standing on the tracks. Just standing in the middle of the concrete platform as the train approached. It was too late to break. The driver screamed, but there was no girl on the tracks. "It was her," some said: a girl who was killed in a traffic accident at Denny and 5th, caused when her father looked up out of his window to see the train pass overhead. The girl whose spirit now cursed the line forever.

Noir film — Ripe pickings at Bumbershoot. All those tourists with their backpacks. Easy to move among the crowd on the Monorail run and pick a few pockets. Grab a few wallets, a few phones, a few watches. Slip off into the crowd before anyone notices. Standing on the platform at Westlake, getting ready to move through the crowd, a tug comes at the thief's sleeve. A kid. "I saw you," the kid said. "I saw you and I'm gonna tell on you," the kid looked around conspiratorially. "Unless you teach me how to do it too."

Seattle Writing Prompts: The Mercer Arena

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

I drove past the Mercer Arena yesterday, and those machine pickers had already started to tear it down. Soon, in its place, will be an extension of the Seattle Opera, room for more of their civic outreach, design and staging studios, and more offices.

The arena started life as the Civic Ice Arena in 1928, a large rink for public skating and fun. The exterior was changed dramatically in the early 60s to fit the vibe of the World's Fair, and during the fair it saw some famous faces: Ella Fitzgerald sang there, as did Nat King Cole, and the Count Basie Orchestra, just to skim the cream from the top of the list.

It was a popular mid-sized music venue. Nirvana played their last US show there. Led Zeppelin played there twice, as did Bruce Springsteen, Jane's Addiction, the Melvins, the Cure, Ozzy, Sonic Youth, Everclear, and yes, even Britney Spears. But maybe, if performances can resonate through time and you can close your eyes and feel their ripples, the one we still feel most today is when Elvis came to the world's fair and played the Mercer Arena.

But still, the venue was best known for sports. The Seattle Totems, a local hockey team, played from the late 50s to the mid 70s. The Seattle Reign started their...well, reign, in the venue, as did the short-lived Seattle Smashers (Vollyball) and Seadogs (soccer).

Personally speaking, this is one venue I'm not going to feel nostalgia for. I know I've been to shows there, but for the life of me I can't remember what they were. It is, in my mind, as it has been by the city for years: condemned. Sometimes you hear of a plan for a place, and you mourn the changes that will take something vibrant and leave something sterile. This is not one of those times.

But still, let us take a moment to tip our hat to the building that has sat empty since 2003, but which once held so many individual memories and experiences. Thanks for your service, Mercer Arena. See you in the building afterlife.

Today's prompts

1927 — They were clearing the ground before they brought the steam shovels in to do the real digging of the foundation for the new ice arena. Reggie was the first to find a bone, but no way it was human, right? But then one of the other fellows found a skull, and another right next to it. No way they were gonna build this new arena on top of an old cemetery, not with the curses that would follow them all. But then that foreman Jack came in, and that dog just spit on the ground and said "Get the truck. I want this land cleared by sundown or I'm docking your pay."

1961 — Her first architectural review. There were competing plans for the new facade of the Arena, to get it ready for the world's fair. She was presenting after the favored firm, Kirk, Wallace, McKinley & Associates, and rumors were they already had it clinched. But their vision was so pedestrian. She was going to show something novel and new, yes, but also something that would change the way people think about this building. They were showing a new skin, but she was showing a revolution. If, that is, she didn't vomit in front of the committee from nerves.

1968 — It was like she had a spotlight on her. You couldn't take your eyes away. Joanie Weston, the Blond Bomber, right here, skating derby in Seattle. She was fast, wicked, and driven. Nobody could beat her. And you, all of six years old, skinny legs and chubby face, wearing that hideous dress with the bow your Mom made you wear that you hated, sitting next to your hollering jerk brother, and there she was owning the arena with her brilliance. It was then you knew what you were destined for, and it wasn't playing with dolls. And more than that, you knew just what you had to to become a roller derby star, just like Joanie.

1997 — Rock show next door to Opera Night. Just a normal evening at the Seattle Center. But when the doors opened at the same time for both venues, tuxes and gowns found themselves mixed into crowds of flannel and ripped stockings and torn baby doll dresses. It was one dude from each, drunk from contraband flasks they squirreled into their retrospective shows because they were mad they got dragged out on game night. They came face-to-face right outside the Mercer Arena, and after shouldering each other because neither wanted to make way, they turned to face each other, and the shouting and fighting began.

2016 — It was just a dare: break into the old Arena and last the night, win $50 from all of their friends. Dead simple. It wasn't like a haunted house or anything. Some big, old, dumb building like this can't be scary, right? Plus, in the backpack, there was a huge maglite, snacks, and they had the big down puffy coat on, gloves, and even some rope for some reason. They were ready, until, that is, they entered the main hall and heard a child's laughter from somewhere up in the rafters.

Seattle Writing Prompts: Lake Washington Boulevard

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

What would Seattle look like without John Charles Olmsted? The famous park designer, who formed the Brookline, Massachusetts landscape architectural firm Olmsted Brothers with his brother Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., was hugely productive. Over the founders' lives (the firm ran continuously from their founding, past their deaths, and almost into the 21st century: 1858-2000), they designed hundreds of parks and college campuses, all around our nation. Their father, Frederick Law Olmsted, was the co-designer of New York's Central Park, and is considered the father of architectural landscape design, so, you know, nothing big to live up to.

Locally, Olmsted designed the University of Washington campus (as the grounds for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition), not to mention Woodland, Volunteer, Cal Anderson, Seward, and Green Lake Parks, just to name a few.

He also designed Lake Washington Boulevard. Eight meandering, gorgeous miles that wind from where Montlake Boulevard and 520 meet, south through the Arboretum, and then ending up hugging the shoreline of the lake, with diversions to curve through parks, until it ends at Orcas street, at the entrance of Seward Park.

Did you know that the boulevard is considered a park? At least, it's managed by the Seattle Parks and Recreation Department. The city shuts down stretches of it a few times each Summer for family bike rides, which are awfully fun. Kurt Cobain lived briefly, and died suddenly, on the street.

Olmsted arrived in Seattle in 1903, called on by the city leaders of the day who were inspired by the City Beautiful Movement, spending most of May of that year visiting sites throughout the Seattle area, learning the land that Seattle owned, and learning of the privately owned amusement parks that Seattle came to buy.

Olmsted imagined a string of parks, connected by boulevards, making emerald ribbons throughout the Emerald City. He even complained of the rain, writing home to his wife nearly daily. Olmsted's plans for the city were submitted in July of that year. The city council adopted it in November.

Lake Washington Boulevard was actually a number of segmented boulevards, but were renamed as one in 1920. If you're feeling uninspired at any time, a walk through one of the parks that it bisects or skirts, or a ride along its lengths by bike or even by those strange conveyances, the automobile, might break some ideas loose in your head. I was so inspired on a recent drive, on the way to our Reading Through It Book Club at the Seward Park Third Place Books. The light on the water. The people out for strolls. The windy slow traffic.

Of course, perhaps not everything is always perfect along that beautiful stretch. Who knows what horrors lurk along along its length? Maybe we can uncover a few of them today.

Today's prompts

Olmsted — He was tired of the company — they seemed to never want to leave him to his thoughts. Some 3,000 miles from his home and family in Massachusetts, not even a walk along this beach was lifting his spirits, thanks to the yammering cohort. Perhaps it was the naked ambition of these Seattle people, so eager to seem sophisticated and worldly. Perhaps it was the damnable weather, always gray and drizzly. He stepped away from his group, saying he'd be back shortly, and climbed up a bluff, into the dense undergrowth. He was hoping to see a vista, a place for a clearing and a bench for a nice panorama of the water, but the foliage was thick enough to block any view from this angle. Then, even before he heard anything, a rank animal musk came across his nose. A branch cracked, as if stepped on by a heavy foot. Taking a rasping breath, he slowly turned.

The walker — Every night that bastard walked his dog. He'd leave his million dollar house with the view of the water and Mercer Island, and walk down to Seward Park. He'd leave the path, and break into the woods, tying the whimpering dog to a fallen tree, before walking on a bit longer. Then, at a little clearing, alone, he would unwrap the little bundle — his most dreaded secret — and prepare the ritual that brought him so much relief.

The child — the problem was that Daddy didn't see. Not really. He'd pick the child up, put them into the seat on the front of the bicycle, and they'd go for a ride along the water. It was so much fun, until they got to the tree. The child would try to remember to close their eyes, but they never could. They always looked up. They always saw. And Daddy never listened when they tried to warn him.

The teenager — He was just minding his own business. Hanging out on the beach, smoking a cigarette. Trying to not get caught smoking that cigarette. The lady looked, like, totally normal. Kind of boring. Middle aged, maybe. Wearing a business skirt and short heels. She had pearls around her neck. She just walked right past, stepping on his backpack, not even noticing. Kept walking. Went right down to the water, and she didn't even stop. Just kept going in, up to her knees, her waist, her neck, and then, swear to god, she went under. I mean, what the hell was he supposed to do?

The grandmother — This was back in the 60s, but she remembers that boy down at Ranier Beach like it was yesterday. He just wouldn't let up, trying to impress his friends and show off, bugging her. So she got on her little bike and rode up the shore. Four miles, if she remembered correctly. Four miles until they chickened out and turned back, getting into the white part of the shore. Four miles to the beaches where it was all white people and only white people. Everybody knew that was a bad idea, but she did it anyway. What was the worst thing that could happen? People are people, and all she wanted was to sit on the beach and read her book in peace. Surely, they'd just let her do that, right?

Seattle Writing Prompts: the PI-Building Globe

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

This globe was first raised over their building at 6th and Wall in 1948. The Post-Intelligencer — a combined name (the Seattle Post merged with the Intelligencer in 1881) that feels like a commentary name — had its headquarters there, in a building that is now housing City University. You can still see the round entry where the globe sat before they moved it to the newer waterfront building in 1986.

The P-I was a Hearst paper. During it's long run, northwest novelists Tom Robbins and Frank Herbert were employees, as was EB White (as in Strunk-and, and Charlotte's Web) for a spell after he got fired from the Seattle Times ("A youth who persisted in rising above facts must have been a headache to a city editor" he wrote later. He also wrote, after reading his journals of his time in Seattle, "As a diarist, I was a master of suspense, leaving to the reader's imagination everything pertinent to the action of my play").

The globe is certainly an icon in this town. Any montage worth its salt is sure to show it. It currently belongs to the Museum of History and Industry, but exactly what they have planned for the big metal ball of steel and neon has not yet been revealed. But, wherever it goes, it will still inform you: "It's in the P-I".

Surely, there were thousands of stories that took place as that globe turned and the desks turned in their reporting. But let's try something different, if you're game. Let's think of a few stories that take place all within view of the PI Globe.

Today's prompts

The Jogger — Back then, going through Myrtle-Edwards at night wasn't the best idea, but a tough guy like him wasn't gonna get scared off his nightly run by some hoods in a park. But when a charley horse in his calf pulled him up short by one of the pocket beaches, he could hear the lapping of the water against the rocks and wood. And he could hear the voice coming up low and stranled, "help me, please!"

The Artist — Finally, a show in New York. Working around the clock was worth it. But the loft space that used to look at the water now looked at that damn new building for the paper. And they lowered that kitschy monstrosity on top, and lit it up, ruining the light in the studio. Nothing doing, the paintings had to get finished. Even if the seeping influence of that glowing ball found its way into them....

The Accident — It was just their luck. The road was wet, just on Elliott where it turned. The Camaro they jacked was powerful, but with bald tires. They slid, sideswiping that other car, then careening into a parked car, smashing the front-end. Now they had to choose: run for it, or stop to help the woman they just hit.

The Informant — He kept to the shadows across from the paper, up their on 6th. He risked lighting a cigarette, then cupped it in his hand so as not to draw attention to himself. That reporter knew where he was. She'd want to know all the details, and he was ready to spill. Damn the consequences. Ain't no good having connections when they all just gonna turn on you. Best thing you can do is turn on them first, and get out of town. That's just what he planned to do. He pulled his hat down to shield his eyes from the rain, and waited to for the dame to get off her duff and come find him.

the Chaplain — The bay was well protected, both by these inland waters they'd been exploring on the Wilkes Expedition — still going strong in 1841 — and by the natural land forms that curved about it. Jared Leigh Elliott, chaplain on the Vincennes, had borrowed a glass to observe the shore from the ships rail. Suddenly, he had a vision through the scope that quite shook him. A vision of a globe, lit by some ghastly ominous light, with letters surrounding, quite clearly spelling "IT'S IN". A moment later, the vision was gone, and Elliott scanned the land again, trying to find whatever it was he surely must not have seen. Wondering if he was having a fit. He heard the steps behind him, knew it was the captain come to chat. Wondered exactly if he should tell him what he had seen. A glowing world. Why would the lord visit such strange visions upon him?

Seattle Writing Prompts: Harborview Medical Center

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

The beacon on the hill! Harborview is infamous in Seattle, a place of great healing, a place most people in the city hope to never visit. A massive employer, with 24/7 staffing. It's the only Level 1 trauma center in the state, and also serves parts of Idaho, Montana, and Alaska. If you've ever seen those red and white helicopters flying fast and low over Elliott Bay, chances are good they're on their way to one of the three landing pads on top of the Harborview parking complex.

To enter the emergency department at night, you pass through metal detectors. It's a nod to the fact that if you're shot in the city, you're probably going to end up at Harborview. And what if the person who shot you wants to make sure the job is finished?

Opened on First Hill in 1931, Harborview began its life in a much more modest way, as a six-bed welfare hospital in 1877, then called "King County Hospital". In 1906 it was in Georgetown, and had 225 beds. Now, after its recent expansion, it has 413 beds.

Hospitals seem like dark places to people who don't work in them, or visit them frequently. They represent our fears, the places we least want to be. But then, I think about Fred Rogers' quote about his mother:

"When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, 'Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.' To this day, especially in times of disaster, I remember my mother's words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers — so many caring people in this world."

The fact is people choose to work in hospitals because they want to help people. If you look at a hospital and see fear, remember to look again and see professionals who will be there for you or your family in times of the most dramatic need.

But then, not every story should be about the good things, should it? There are a million stories in the naked hospital, and I only have foom for five writing prompts.

Today's prompts

- The rain is coming down in slanting waves, and maybe it wasn't smart that the bird was flying at all in this, but when somebody needs help, those helicopter pilots push their luck. The EMT was sitting in the ambulance, and after the wheels touch down, the EMT waited for the rotors to stop like regulation says. But then the helicopter door buckles. A face presses against the windshield in a scream. The door flies off the side with amazing force, and a dark blur exits into the inky night. The EMT rubs their eyes. What the hell was that? The rain beats down in waves.

- Parking passes are impossible. You work in the hospital? You talk to one man. He's cornered the market. He knows how the system works. He's greased the wheels, and now you have to butter up to him if you don't want to pay through the nose for the day rates. He's one of the highest powered surgeons in the city, so this is just a fun side game to him. If he doesn't like you, there's no way you're gonna be able to park. Too bad you're the auditor who is here to investigate him.

- It had to happen on her shift. She had a lot of beds to cover, but they put those two in the same room. One, a machinist biker who got his knee smashed by a little old lady in a Mercedes. Totaled his body and his Softail. The other, a computer programmer who got drunk and fell of a balcony. All was chill for most of the night, and then the two of them started talking politics. Now it was full on war between two immobilized pissed-off men. And their families.

- That little damn button. It takes away the pain, but it makes everything groggy and sleepy. Still, the patient pushes it when the pain makes everything else seem inconsequential, and tries to sleep the rest of the time away. But one time, that reassuring beep doesn't happen. It's been hours, surely. And furthermore, where is the nurse? Someone should have come in twice in the time its been. And the patient was hungry. Where could dinner be? And why does it feel like the entire hospital is deserted? In fact, why couldn't they see the lights of the city downtown like usual?

- This was what they always did. When first in college, they wandered every hall in every building, finding every nook and cranny. Mapping all the places they could go, and the places they could go, but probably weren't allowed to. So now, in their first weeks as a residence, knowing the sprawl of this massive building was something important. Is there roof access? Can you get up to the walkway around the tower? Which elevators are the fastest? What are the most efficient routes? What they didn't expect was that door in the lowest levels of the basement. And more than that, who could have expected what, and who, was behind it when they found it unlocked the first time they tried?

Seattle Writing Prompts: the Macy's sky bridge

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Standing on the northeast corner of Third and Stewart, looking south on Third, one sees a sky bridge. It connects a parking garage to the building that once housed The Bon Marché, one of three powerhouse retailers that bounded out of the wellspring of Seattle in the olden days. The other two being, of course, Frederick & Nelson, and the still-standing, and now heavily politicized in the age of Trump, Nordstrom (which stands, ironically, in Frederick & Nelson's old building).

The Bon — now a Macy's that is downsizing its store by selling floors of office space where once there were mattresses, kitchen goods, fine crystal, and other standard department store fair — stood connected to its parking garage by this one appendage. I can't tell you how many times I've crossed it, on the sixth floor.

We don't have many sky bridges in Seattle (if you're from the Midwest, you may know them as skyways), there's one a few blocks east connecting Nordstrom to Pacific Place Mall; there's a long windowless one that walks across the roof of the King County Administration Building — that diamond faced wonder caught between the jail and the King Country Superior Court — for walking prisoners from their cells to their hearings; there are two in the Market, and up the street, one from the end of Lenora to Alaskan Way; there's the massive bridge that connects the two parts of the Convention Center where it's bisected by Pike, an expanse turned into display area during conventions, where goods are hawked above the bustling streets of the city, much like bridges in olden Europe used to contain apartments and stores.

It turns out we don't have many sky bridges because the city makes property owners pay for them. Macy's, in fact, paid a fee of $31k back in 2010 for this very skybridge, up from the original $300 when it opened in 1960. Or, about the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Seattle.

Seattle politicians aren't very circumspect with their views on the rank inequality of sky bridges:

“What a sky bridge does is it takes people off of the right of way and puts them up in the air, and leaves usually the people who aren’t good enough to go in the buildings down below,” City Council member Jean Godden said. “It’s really not very friendly.”

Surely, given all this, we can find our way around some writing prompts that take place stories above the street?

Today's prompts

- The ticket booth on the west side of the bridge had a little window, but when she was working, tucked back in there, she couldn't see down the length of the bridge. But, they gave her a little screen attached to a camera so she could see who was coming. Except, that evening, the camera went dark just seconds before she heard the gunshot.

- It was really strange. Never before had Snowy done anything but execute his duties as a seeing eye dog with aplomb. Yet, this morning he wouldn't budge at all. Half way across that damn sky bridge, he sat down and turned into a statue of a dog, resolute and still. What could have made him do that, all of a sudden?

- He was terrified of heights. Every step across the bridge always came with a prayer that the big one wouldn't strike while he was on the bridge. Turns out, maybe he was worried for a very good reason....

- Maybe it was unromantic. Her friends certainly tried to talk her out of it, but if there was one thing that brought the two of them together, it was their love of sky bridges. And since she'd be the one proposing, she was gonna do it as she damn well pleased.

- It was kind of amazing, the sort of thing you'd never expect, the sort of transformation that only happens once in a person's life. But there she was crossing back to her car, and what had happened in the past hour inside the department store had changed her so much, that she barely recognized the woman in her memory who had crossed the other way not even an hour ago.

Seattle Writing Prompts: SeaTac Airport

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Using the word-mashing logic of SeaTac, we should have named the lake to our east SeaBelle. To the North, perhaps we could make a region called SeaEver, and perhaps our ferry runs could be SeaBain, SeaVash, and SeaBrem.

But despite its awkward name — and being one of the only cities in the world, to my knowledge, that employs CamelCase — we do all find ourselves drawn to SeaTac's engine-roaring shores now and again.

This time of year, the smart are taking short jaunts to points south for some mid-winter sun. Not that bright, I flew to Chicago last weekend (it was quite nice, in fact, so you can keep your Mexican sun weekends for now).

Airports are one of the great transition points of the world, and although they are also now ridiculous semi-public undressing places, once you're through the curtain of security there are delights to be had. Just wandering the terrazzo floors, gate-to-gate, looking at weird little shops and people who are either late and rushing, or early and dragging.

And every plane that takes off or lands, in those two-minute spreads, is full of people jetting through the air at tremendous speeds, carrying with them all the stories of their lives. Some of those stories, surely, happen because of people coming together in unexpected ways at the airport. I'll bet we can exploit that for some good writing fodder today, yes?

Today's prompts

- In security — Why had he worn the tie shoes? Of course the laces knotted when he was trying to get them off at security. And behind him was one of those pushy people reaching in front of him to grab trays before he had his stuff settled. And his pants were falling down without his belt, and he dropped his phone and it nearly cracked. Then, when he was just about to walk into the backscatter machine, right as his bag was going through the x-ray, he heard the scanning agent yell out "bomb!", and people came rushing in.

- In the secure zone — She hadn't gotten a license to practice massage just to rub the shoulders of travelers in the airport, but a job is a job and this one came with benefits. She almost never saw anybody she knew, except that one day where she was pushing her elbow into the back of some businessman and she saw her sister walk by the booth. Her sister that had disappeared ten years earlier...

- On the plane — It was just a fact of life: never speak Arabic to a friend or on the phone when you board a flight, lest some scared white American have a paranoid waking dream about you, and suddenly police are taking you off the flight. So when that woman across the aisle started looking, there was nothing to do but ignore her. But when she leans over, as the airplane starts taxiing, and says "I know who you are", there's nothing to do but listen to what she's gonna tell you.

- In the terminal — Nobody knows how the raccoon got through security to begin with, or why somebody had it as a pet. But there's one thing for sure: a scared raccoon in an airport is a serious disruption, and as the new security guard on duty, it was gonna be their job to catch that furry little bugger and put it back where it belonged.

- In baggage claim — In one of the greatest coincidences in the world, they had almost met five times before they had their first date. Each time, was in the airport, waiting on luggage. Each time, had they seen each other, they would have fallen in love. Each time, some twist of fate kept them apart. Five twists of fate conspiring against two people. Just think about what could have happened....

Seattle Writing Prompts: Kerry Park

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Ah, Kerry Park. As Seattle views go, it's hard to beat this one, and that's in a city with more vistas than West World. Have you ever been? It's crowded, nearly all the time (except, ironically, the day I dropped by to take these photos).

On a clear day, you can see Rainier, and if it's dusk, you can see the lined-up jewels of planes in formation on their way to SeaTac, no doubt each one carrying excited tourists, those eager to be home, and flight crews eager to knock off shift. If you're the kind of nerd that loves sighting expensive camera equipment in the wild, the lenses used here will surely impress. Everybody brings their best gear to Kerry Park. The opening credits to 10 Things I Hate About You were filmed there, as was the cover photo of a 1989 hardcore album by the band Brotherhood, which I only know about because one of their fans (or band members) made note of it on the Kerry Park Wikipedia page.

The park was a gift of Albert Sperry Kerry (that name!), and his second wife Katherine Amelia Kerry (his first, Mary Ellen Kerry, died young). He lived at 421 Highland, just down the street from the park, which the Kerry's donated to Seattle in 1927. The famous sculpture in the park, Doris Totten Chase's Changing Forms was commissioned by Kerry's three children, and installed in 1971.

People come to Kerry Park mostly for the view, but I love to walk through Kerry Park to look at all the people looking at the view. Teenagers cruising in cars with loud stereos, tourists who heard that it can't be beat, Queen Anne residence jogging by or walking their dogs, wedding photographers shooting couples in full dress, photographers with massive tripods shooting golden hour, it's a busy intersection, and that gives rise to so many story possibilities.

So here are a few, all of which may have happened, in Kerry Park, today...

Today's prompts

- 5:35 am — She was always nervous about jogging before the sky got light, but if you want to run marathons, you don't let fear stop you. Running with a friend always helps, though, and that day Joanie was going to meet her at Kerry Park, to run the loop around the hill a few times. What she wasn't expecting was to see the still body laying on the grass, wearing what looked like Joanie's running jacket.

- 10:12 am — An accident in front of the park. Happens all the time, fender bender as the morning light was particularly sparkly on downtown and the Space Needle. The difference, is that usually people who hit each other don't fall in love. And these two almost don't themselves, until their argument about who was at fault is interrupted at just the right time.

- 1:30 pm — Twice a day, on nice days, the three of them go up the hill. One is the bride, one is the groom, one is the photographer. They rotate through the roles. The bride always starts the fight. She runs off with the photographer. The poor groom is left, bereft, to find a way home when he has no money. Stupid sucker tourists....

- 6:45 pm — The end of the reunion. It took a year to plan, people flew for thousands of miles to come, and the family had never felt so close. All twenty of them would be leaving tomorrow, but they decided to do one final group picture with Seattle in the background. Each one has a memory of the past few days and what they learned about people they thought they knew. Each has a new secret to take home with them. Each one deserves their own short paragraph. Where did they come from? What is their relationship? Who is the oldest person in the family? The youngest?

- 11:59 pm — He didn't spend two freaking million dollars on a condo with the best view in Seattle only to be woken up at midnight by some goddamn band in leather and white pancake makeup — god, wasn't KISS passé!? — pretending to play their pointy guitars while a car blasted their godawful racket and some production interns shined red gelled lights on them, and idiots with cameras shot low angles to make them look wicked. He was going to give them a piece of his mind. And since they were all probably drug addicts, he made sure to grab his pistol. Just to protect himself, of course.

Seattle Writing Prompts: More Moore

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Theaters have a special place in the history of cities. It's more than memory, although I've certainly seen some notable performances at the Moore Theater over the years (odds are pretty good you have as well). Theaters take up a huge amount of space on the grid, but are only lit up with activity and people a few hours a day, at best. The rest of the time they lay in wait, a few people prepping, practicing, staging, or constructing, but otherwise, they're empty.

During the day, the gates across the front entrance may be slightly cracked, and you wonder who is inside. Perhaps you catch the person changing the letters on the marquee. Perhaps you think you hear sound check leaking out. Perhaps you see the tour buses, the sides popped out to allow for more sleeping space, parked in front or on Virginia between 2nd and 3rd.

The Moore is the oldest still-active theater in Seattle. About half the capacity of the grander Paramount across town, the theater feels both grand and tiny when full and a performer is on stage. You can see the expressions on their faces, the intimacy is something amazing.

It opened in 1907, which means as its doors were first thrown wide, just north workers were still sluicing away parts of Denny Hill, in the second regrade effort. The Moore's purpose was to house (in the adjoining hotel) and entertain visitors of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, a grand world's fair in 1907 (we all know what the fair grounds of the 1962 world's fair became, so what became of the grounds of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition? They became the University of Washington campus).

For many years the Moore was a movie palace, and under the name Moore Egyptian it hosted the first SIFF festival in 1976, before the folks that ran it moved the theater to the old Masonic Temple on Capitol Hill, and kept the Egyptian name.

The Moore has a second balcony, that has a separate entrance off Virginia, which bypasses the grand lobby, and offers more modest bathrooms. Speculation is that this was for racially segregating theater goers, but historians have not been able to uncover definitive proof. Other speculation is that the balcony was for economic segregation, which was defacto racial segregation as well. Feliks Banel wrote a great piece on this that was published on My Northwest.

Now, isn't that enough to give us some ideas to write about?

Today's prompts

- The theater is dark. A match strikes and flares, a candle is lit. A quavering hand walks it across a bare stage, one shy step after another, all the way to the front. The candle is placed, ever-so-carefully in front of its bearer, who clears their throat, and addresses the supposedly empty theater with something they've wanted to do in public their entire life.

- The theater is bustling, and outside the door on Virginia, trying to hustle a fifty-cent ticket to the high balcony, is our hero. There's a Vaudeville act coming through they keep hearing about, and they're gonna see it no matter what may come. The ticket acquired, they hop the stairs two at a time to get in, and grab an empty place on a wooden bench up front. But when the first act rolls out, they see that rich fellow who did them wrong, sitting right down there on the floor. Nothing — and I mean nothing — is gonna stop them taking their revenge.

- The theater is about to riot. The crowd is sick of waiting. They're booing, throwing illicitly imported bottles at the empty stage. The stage manager goes once more to try to convince the band, now an hour late, to get a move on. They're doing lines and gulping whiskey in the dressing room. But at the sight of the stage manager, they decide it's time. "Fucking singer been gone a long time" one of them says, and another goes over to knock on the toilet door. It opens. There is the singer, slouched on the toilet, needle in arm.

- The theater is rented for the afternoon. There's a single mic on stage, and only twenty-five people in the audience. Nobody can believe they got this lucky, especially that person sitting right in the middle, who is holding an envelope from the DNA testing firm that conclusively proves that the man about to walk out onto the stage is, in fact, their father.

- The theater is closing. Who goes out anymore? Everything is virtual reality now. Every seat is front row. You could sit on the damn stage if you want, and feel it when your favorite musician walks over to you and kisses you. But there's one more night to get over first, and it's gonna suck. Touring asshole comedian, the house not even half sold. But then, in a standard security sweeping, someone finds a duffel bag tucked under a seat. And inside, it sure looks like a bomb.

Seattle Writing Prompts: ghosts and fires

New column! Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

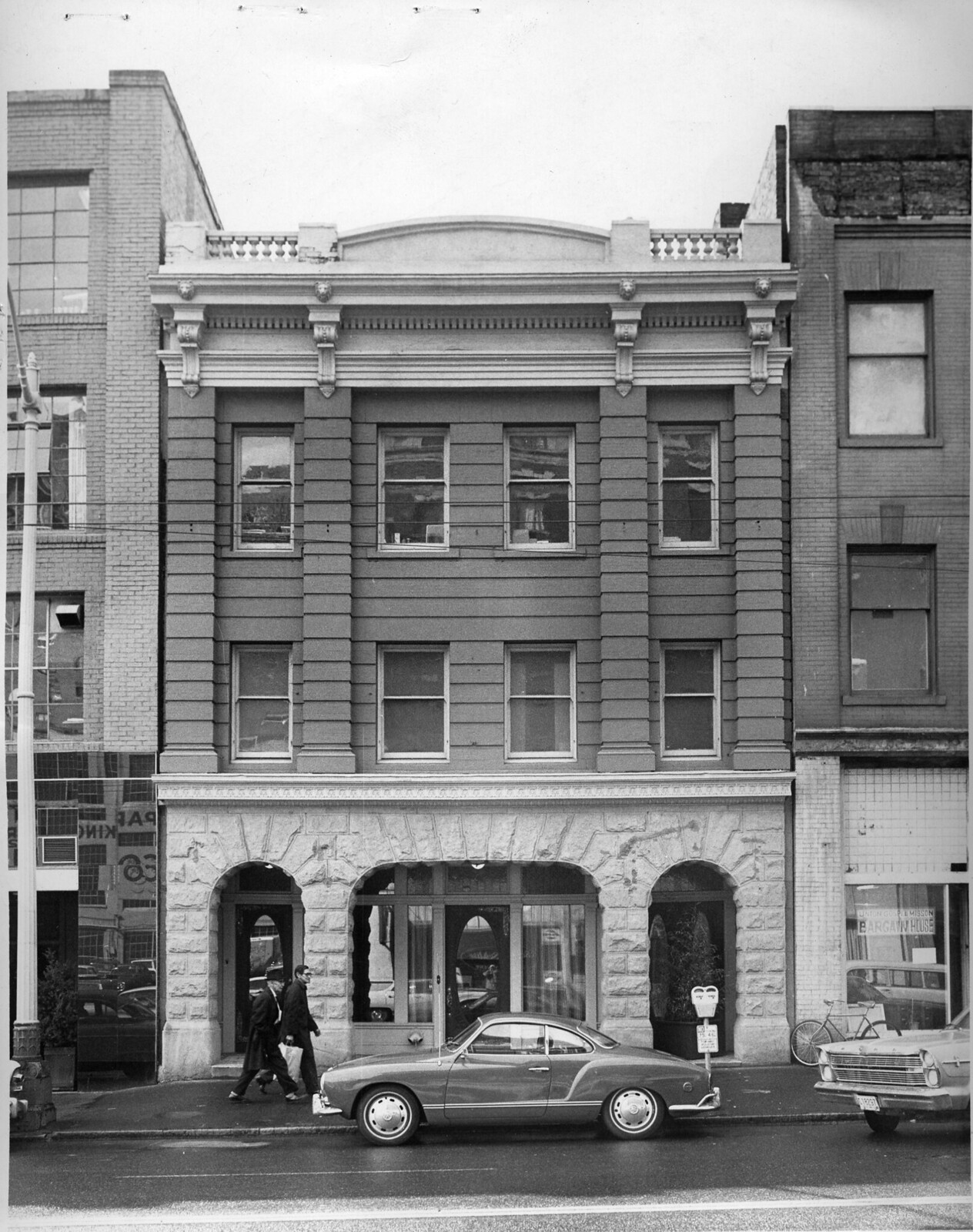

The Butterworth Building is haunted. Just ask anybody who works at Kells, the Irish pub in the basement of the building.

Opening in 1903, purpose built as a mortuary for the firm Butterworth & Sons, it was likely the first building in the United States to provide full mortuary services under one roof. In fact, the grand man himself, Edgar Ray Butterworth, is credited with having coined the terms mortuary and mortician. So, take that, rest of the world who then adopted terms invented in Seattle. Tell all of your funeral-nerd friends!

Speaking of firsts, it was the first building on the west coast to have an elevator — although the 1st avenue face of the building is only three stories, if you walk around back to Post Alley, you'll find another two below them. Kells is in the former embalming room and crematorium, or the stables and storage for funeral wagons, depending on who you believe.

The building was in the news a few weeks back after catching fire, which is when I started reading about it. Isn't it funny how this little three-story wonder can have such a history? At the end of the post, I'll include a second shot from Flickr, when the building was an engineering firm in the 1960s.

If you search for information about the Butterworth Building, you will find many writings talking about how haunted it is.

All of which gives us some nice potentials for:

Today's prompts

- You're a bartender at Kells, and it's closing time. You just got the drunks out, and the last load of glasses put away, and the bar wiped down. The door — you swore it was locked — opens, and a man in black stands before you.

- You're a kid, eight years old, and you were chased out of the market after stealing an apple from a fruit-stand. You hide in the old mortuary stables, and you overhear the stable boy talking to a girl he fancies, and he tells her something that changes your life forever.

- You're a firefighter, and you enter a smoky room at the top of the building, wearing your respirator. You're making sure the place is clear of people. A buzzing sound and flickering light catch your attention. A device, metallic and round and decidedly futuristic catches your attention. You reach out for it...

- You work in the engineering firm on the ground floor, as a draftsmen. You're working on a piece, cigarette in mouth, when a cop walks in. Talks to your boss. You see the boss point at you. The officer removes his hat and walks towards you with a sympathetic look on his face.

- You're a construction worker excavating years of really crappy remodels inside the Butterworth building. You're working on this one part of wall, when you feel a loose brick. It wiggles free, and a blast of cold air hits your face. You put your flashlight up and look inside....

Seattle Writing Prompt: the pyramid atop the skyscraper

New column! Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Did you know that someone lives atop Smith Tower? Petra Franklin Lahaie holds the lease. She cleared the space after a water tower was removed, converted it into an apartment, and made her home there with her family and her massive Chihuly chandelier. The New York Times did a great piece, with photos, and Evening Magazine took their cameras inside in 2011.

What a stellar piece of Seattle skyline that building is. A wood frame skyscraper 38 stories tall, the tallest building "west of the Mississippi", as we like to say in Seattle, when it was built, Smith Tower opened in 1914. Its builder, Lyman Cornelius Smith, whose moniker you may know when attached to the company name Smith Corona, bought the land when on a trip out west from his native New York in 1909. Did you know the building still employs elevator operators?

Ivar Haglund once owned the building, as did the property holding firm Samis, a company started to control the interests of that other Seattle iconoclast, Sam Israel (somebody really should write a book about him), a few years after their namesake died.

But it's that apartment at the top that has always captured my fancy. Here are five writing prompts based on that pyramid, and Smith Tower.

Today's prompts

- It's 1915 and the newly opened building was built with the apartment up top. Who lives there? What is their daughter like? Does she get into trouble and go on adventures?

- It's 1975, and an elevator operator in Smith Tower witnesses a murder through the door cage as he is going down. Worse yet, the murderer saw him. Was he alone in the car? Does the story all take place inside of one hour? Does it spark something bigger? Do they end up in the pyramid as it was, with the decaying water tower?

- It's 2000 and the Kingdome is about to be demolished. What does a young street hustler have to do to get up to the top to watch the destruction? Can they even make it? Can they make it to the glass bulb at the very top?

- It's 1941 and German and Japanese aircraft are bombing Seattle. What can people in the building do to keep it safe? How can they fight back against air-strikes, like London saw during the Blitz. What if there's a German traitor in the building?

- It's 2025 and the big one hits. Who works on floor 15, what part of Seattle do they need to get amidst the rubble, and how will they get there? Do people die? Does the building go down?

Introducing (again) Seattle Writing Prompts

The humble writing prompt is such a great device. When you're stuck, as a writer, often times the perception is that there aren't any ideas, and that the world is bereft of good plots.

Given the idiosyncrasies of human thinking, what's maybe going on is that you are stuck in your own loops. Prompts, from the brain/emotion loops of other humans, can be helpful to spark an idea. Other's ideas surprise you, like the punchline to a good joke, and in that surprise comes a stepping out of yourself into another possible imagination. A good prompt, taken in at the right time, can enlarge our ability to write. Or, at the very least, help us find momentum until our true work interrupts to call to us.

When we started the Seattle Review of Books, Paul wrote a couple Seattle Writing Prompts. We both love the idea, but they kind of fell by the wayside, and the other work of the site took precedence.

So when the Kickstarter Fund Project was coming to an end, I decided this would be a perfect form to run on Saturdays. First, because a lot of people only get to write on the weekends, and as they're sitting at their desk, or coffee shop bench, or room with a view, or library to write that day, maybe they're in need of some inspiration. Second, because I've lived in this city a long time, and I love talking about different parts of it.

The form the new column will take is to show a picture of a Seattle location, talk a bit about it, then list five potential prompts. The whole thing is to get you thinking of ideas, concepts, and places that you might be outside of your immediate purview. Maybe some thing in the post will spark an idea, and maybe the idea itself will come not from any of our writing, but from your own loops, newly engaged.

Look for the first of the Saturday Seattle Writing Prompts to go live later this morning. And get to work!

Seattle Writing Prompt #2: Writing the city

Ask any writer: the two most difficult parts of the writing process are 1) sitting down in the seat to write and 2) figuring out what to write about. We can't help you focus on your work, but we can try to help you find inspiration in the city around you. That's what Seattle Writing Prompts is all about. These prompts are offered free to anyone who needs them; all the Seattle Review of Books asks in return is that you thank us in the acknowledgements when you turn it into a book.

I haven't read that many good books about graffiti. Jonathan Lethem's Fortress of Solitude is the first one that comes to mind, though I know I've read others. Why isn't there more good fiction about graffiti? Don't writers love to write about writers? And aren't graffiti artists just another kind of writer, explaining the city around them?

If you're having trouble finding inspiration, go take a walk. Focus on noticing the graffiti. When you find a piece that speaks to you — maybe it's half-finished, maybe it's clever, maybe it's crude — try to write about it. What was the artist trying to say? What are the different ways the piece could be interpreted? Where's the artist right now?

If you're unable to go out for a walk, my friend Renée Krulich has a world-class Flickr stream on which she documents seemingly every single piece of graffiti in Seattle that she can find. They're all organized in albums alphabetically by artist, from famous names like John Criscitello to sticker artists like 'Phones. Personally, I'm fond of Sti(c)kman and Allo, but you can choose whomever you like. Or maybe you finally want to get to the bottom of the eternal Seattle question: what's the deal with SHITbARF? There must be a novel there. At least.

Seattle writing prompt #1

Ask any writer: the two most difficult parts of the writing process are 1) sitting down in the seat to write and 2) figuring out what to write about. We can't help you focus on your work, but we can try to help you find inspiration in the city around you. That's what Seattle Writing Prompts is all about. These prompts are offered free to anyone who needs them; all the Seattle Review of Books asks in return is that you thank us in the acknowledgements when you turn it into a book.

The opening paragraphs of this Seattle PI story by Daniel DeMay are so vivid and intriguing that they're practically the beginning of their own sci-fi novel:

Imagine a greater Seattle area that is clearly thought out, directed and completely planned for.

Rapid, subway transit lines connect east to west, north to south and neighborhoods across the city. An above-ground rail line links Everett to Tacoma and passes through a central station where Roy Street now intersects with Highway 99.

Downtown buildings are capped in height, much like Paris, so as to let light into downtown streets. Mercer Island is one big park, restricted from development. And city government offices are condensed in a grand civic center across Denny Way from where Seattle Center now sits.

All this and more was envisioned by Virgil G. Bogue, an engineer and -- some might say -- visionary who came to draft a sweeping plan for Seattle in 1911.

Go read the whole great story to find out why we're not living in Bogue's Seattle. And then think about what would have happened if Seattle voted for Bogue's plan in 1912. What do you think everyday life would be like 100 years later in that Seattle? Would it be an urbanist utopia, or an antique-looking steampunk wasteland? Take a walk and try to overlay Bogue's vision on top of the city you see. Then write about it. Let us know if you come up with something interesting.