Archives of The Sunday Post

The Sunday Post for March 4, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

How to write a memoir while grieving

When Nicole Chung’s father died, she was still writing the story of her family and her adoption — the memoir was due to her editor just one day after she found out he was dead. Here she explores how both the book and the loss of her father pulled at the threads of their family, loosening some and tightening others. There’s something sinuously meta about this piece; she’s writing a story about writing a story that’s taking place while she’s, um, writing it. And also something remarkable about the gentleness and honesty with which she navigates that looping narrative.

Someone recently asked me how my dad’s funeral went, and I said, “It was beautiful. My mother was really happy with how it went. And my sister was there with me, which was so kind of her.” The person nodded, looking a little confused. Isn’t that obvious? their expression seemed to say. Of course your sister was there. “Oh,” I said, “no. She didn’t have to be there. We don’t have the same dad. Ah, but we do have the same parents.” They just kept looking at me, like, Sorry, you’ll have to give me a bit more.

Sliced & Diced

It’s not easy to make statistical method scandalous, but Stephanie E. Lee achieves it with her story about Brian Wansink. Wansink is a rockstar of social science (if such a thing exists), head of the prestigious Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University. He’s published dozens, if not hundreds, of studies in peer-reviewed journals, many of them headline-worthy. Turns out it’s not that hard to do newsworthy science, if you start with the headline and trim the data until they fit.

In 2012, Wansink, Payne, and Just published one of their most famous studies, which revealed an easy way of nudging kids into healthy eating choices. By decorating apples with stickers of Elmo from Sesame Street, they claimed, elementary school students could be swayed to pick the fruit over cookies at lunchtime. But back in September 2008, when Payne was looking over the data soon after it had been collected, he found no strong apples-and-Elmo link — at least not yet. “I have attached some initial results of the kid study to this message for your report,” Payne wrote to his collaborators. “Do not despair. It looks like stickers on fruit may work (with a bit more wizardry).”

Covert cooking: how to bake a pie in prison

Take May Eaton’s piece on baking behind bars with a grain of salt (no pun intended); in the prison experience she describes, contraband means stolen meats and bartered bananas. A missing stapler isn’t stolen for use as a weapon, just mis- or mischievously placed in a waste bin. Prisoners fabricate Faberge-like eggs as gifts.

That’s not to invalidate what she has to say about the persistence of the need to make, to create, even when freedom is limited in the most severe ways; her essay is both interesting and inspiring. But after you read Eaton, balance it out with Jerry Metcalfe’s first-person account of the life prison normalizes for most people held inside.

I still didn’t understand how a handful of ingredients could be turned into a pie that looked and tasted almost as good as one you’d find on the other side of the fence. The prisoner tapped his nose, reluctant to divulge a trade secret, before ego got the better of him. First, he explained, he had stripped the insulating cable on his hi-fi, using the exposed wire to “defibrillate” a can floating in a tub of water, instantly transforming condensed milk into dulce de leche. Pour the caramel over some crushed biscuits and top with mashed banana and you had banoffee pie.

The Sunday Post for February 25, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

I thought my bully deserved an awful life

Geraldine DeRuiter, the blindingly smart author and blogger, did an online search for her childhood bully, hoping for the usual comeuppance story. Instead she found her tormentor had died — young, scared, and alone. The essay she drew from that experience isn’t an apologia for bullies, who can do a hell of a lot of damage, but it’s a reminder that the forces that turn kids into bullies can be ugly. Does hating your bully turn you into a bully? Ugh. Thanks for the wake-up call.

I read that he had anticipated an attack. His friends said he was so terrified in the weeks leading up to his murder that he’d slept with a hammer under his pillow. I was haunted by what I imagined his final moments were like, by how scared he must have been. I cried for the boy who had made me so miserable.

Now I had to wonder: What kind of fate would I have considered sufficient retribution? Would I have been satisfied if he was merely unsuccessful or unhappy? What sentence are we comfortable bestowing upon a fifth-grader for his crimes? What’s the statute of limitations for revenge?

When Whisper Networks Let Us Down

A very long read but a worthwhile one by Sarah Jeong, who reported on the rape and abuse allegations against Morgan Marquis-Boire for The Verge. Here, Jeong talks about why whisper networks have failed to protect women against men like Marquis-Boire, men who exhibit clearly violent behavior but do so under cover of social status and of a host of other caveats and codicils. Given an excuse to excuse men for hurting women, we have; it’s time, Jeong says (and our social chorus will continue to say, I hope), for that to change.

The stories carried by whisper networks are easily subverted, especially when the accused has enough social capital. Journalist Anne Helen Petersen connects the concept of whisper networks to the function that celebrity tabloids and gossip magazines often play in the entertainment industry, and to how gossip and whispers of any kind are socially stigmatized as a feminine vice. She describes how “pun, innuendo, and blind items” in celebrity tabloids had long pointed to the truth about Weinstein and his normalized “casting couch,” hiding alleged nonconsensual assaults behind consensual encounters both real and imagined. But the same tabloid press went all out to smear Ambra Battilana Gutierrez when she wore a police wire to record Weinstein’s admission that he had groped her. “Harvey Weinstein rapes women” could also be heard as “Harvey Weinstein sure gets in a lot of trouble with crazy sluts.” The signals inside the whisper network can become corrupted, and sometimes, the connections fail because the carriers choose to protect the accused.

How Black Panther Asks Us to Examine Who We Are To One Another

SPOILER ALERT: save this for later if you haven’t seen Black Panther and care about spoilers. I have not yet seen Black Panther and usually do care about spoilers, but I read anyway. There was no way I was passing up an essay by friend-of-Seattle Review of Books Rahawa Haile.

Haile articulates a deep joy in the movie side by side with equally sharp criticism; she takes this movie seriously in a way that no other superhero film (no, not even Wonder Woman) has earned. And I’m happy to have read this before seeing Black Panther — happy that my first experience of it will be through her lens. There aren’t many reviews about which I’d say the same.

How then does one criticize what is unquestionably the best Marvel movie to date by every conceivable metric known to film criticism? How best to explain that Black Panther can be a celebration of blackness, yes; a silencing of whiteness, yes; a meshing of African cultures and signifiers — all this! — while also feeling like an exercise in sustained forgetting? That the convenience of having a fake country within a real continent is the way we can take inspiration from the latter without dwelling on its losses, or the causes of them. Black Panther is an American film through and through, one heavily invested in white America’s political absence from its African narrative.

Besides I'll Be Dead

Just a reminder that while our attention is diverted by the daily Twitter Trumpfeed, the oceans are rising steadily and will soon kill us all. Meehan Crist on why we’re so comfortable ignoring this uncomfortable reality.

How do you mourn the loss of someone whose hand you can still hold? How do you mourn a home increasingly prone to flooding, but not submerged, yet? The parallels aren’t perfect, but even the disjunctures reveal how wickedly hard the problem of climate grief can be. When a beloved person is slowly disappearing into the fog of senescence, the endpoint is known. With rising seas, the endpoint remains unknown. Three feet? Eight feet? Grief is stalled by uncertainty. For what eventuality should you and your community prepare? Of what do you need to let go in order to move forward? The incentive to wait and see is powerful.

Worst Roommate Ever

William Brennan investigates the first nightmarish, then tragic, story of Jamison Bachman, a serial squatter who posed as the perfect roommate then used escalating legal and physical threats to take over his hosts’ homes. A law education makes him a formidable annoyance in court; his presence on the grounds gives him destructive access to everything from bathmats to beloved pets (in one case, he started dropping his landlord’s cats off at local kill shelters). A broken man who did a lot of damage — and most, in the end, to his family and himself.

Bachman wasn’t a typical squatter in that he did not appear especially interested in strong-arming his way to free rent (although he often granted himself that privilege); instead, he seemed to relish the anguish of those who had taken him in without realizing that they would soon be pulled into a terrifying battle for their home. Nothing they did could satisfy or appease him, because the objective was not material gain but, seemingly, the sadistic pleasure of watching them squirm as he displaced them.

The Sunday Post for February 18, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Great Stink

Laurie Penny somehow manages to be deeply compassionate toward men who treat women badly, without surrending a single ounce of her righteous, blazing fury. In this piece, she explores what men’s feelings require of women during the #metoo moment — and how the kneejerk instinct to protect and mend may be just as damaging as the impulse to rage and reject.

Self-hatred makes people selfish. It deserves compassion, but not indulgence. Women — and I’m sorry to have to break this to you — are not put on this earth to make men feel better about how inherently awful they are. Most of us would prefer the men in our lives to stop wallowing and get on with being a little bit more considerate than they were yesterday, because that is what it means to grow the fuck up.

So no, I don’t hate men. I hate how brittle and fragile modern masculinity is; how it reacts to any perceived threat by lashing out and shutting down. I hate how part of our worn-out script of maleness is by definition resistant not just to change, but even to the thought of change, and how tightly swaddled the whole thing is in shame and silence.

The Final, Terrible Voyage of the Nautilus

Imagine you’re a guy with the means and desire to build a crazy-ass high-tech submarine, and you do; and you’re also a guy with the means and desire to lure a freelance journalist on board with the promise of a story, torture and kill her, and you do; and then you sink your incredibly expensive high-tech submarine to try to cover the murder.

Now imagine you’re another journalist, a friend of the dead woman (stay with me, this is going somewhere), and you investigate your friend’s death and write about it, including how even being dismembered might be something that you were “asking for.”

That’s this, by May Jeong. Read it.

In the days after she disappeared, I heard people ask questions that betrayed a misunderstanding about reporting — couldn’t she have done the interview over the phone? — and casual sexism — why was she there alone so late? On nights when I couldn’t sleep, I would end up on internet chat rooms where the comments sections filled me with rage: “She is a woman — how could she go alone with a man she does not know?” And: “She had skirt and pantyhose—how could she egg on a poor uncle in that way.”

On Writing For Love Or Money

Alexander Chee’s latest newsletter contains a truly excellent manifesto about why writers should expect, and ask, to be paid. The fact that there’s social stigma around this is nuts. If you’re afraid that asking for money means you aren’t a “real writer,” read this and boldly go forth into a new and shame-free world.

And then yesterday morning, I received an email from someone assisting in the editing an anthology. She had made the assumption that my silence in response to her and her co-editor's last email was due to the fact that they can't afford to pay anyone, and so she wrote to me, acting as if I was snubbing them because of the money issue, and quoting from this essay at BuzzFeed back to me. I had written there that you should write for money and love both but money more than love. And she seemed to think it was a sign I was a callow creature hell-bent only on profits, and not someone who had so often gone broke because of writing for love.

Billionaires gone wild

Inside baseball, but fascinating: Alex Pareene dissects the role billionaires play in sustaining, and thus shaping, the media landscape. Read this even if you think you don’t care; by the end, you’ll care very much.

What’s happening to the press is reflective of the broader transformation of our society. Rule by supposedly benevolent technocratic elites is giving way — in large part due to the fecklessness of those technocrats — to straight plutocracy. And really, that only makes sense in an era in which everyone feels like their lives are, in important and fundamental ways, in thrall to the whims of a few mega-rich people. Our cities promise to remake themselves to please Bezos. A few GOP donors threaten to close their checkbooks, and the entire federal tax code is sloppily rewritten. Chris Hughes sneezes, and The New Republic catches a cold.

The Good Room

Frank Chimero brings a designer’s sensibility to the question of the kind of rooms we choose to inhabit, when we choose to inhabit the internet. If we don’t like the ones we’ve made, why not imagine new rooms — and go live there? Despite its starry-eyed start in the New York Public Library, this is a solid piece about the commercialization of digital community space, and a reminder that we’re not at the mercy of the technology we use. Quite the opposite.

Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon aren’t going anywhere at this point — nor should we expect them to — so it’s best to recalibrate the digital experience by increasing the footprint and mindshare of the kinds of cultural and communal value they can’t provide. The web isn’t like Manhattan real estate — if we want something, we can make space for it.

Different measuring sticks are also in order. If commercial networks on the web measure success by reach and profit, cultural endeavors need to see their successes in terms of resonance and significance. This is the new game, one that elevates both the people who make the work and those who see, use, and enjoy it.

(h/t Tim Carmody via Kottke.org. And while we’re on the subject of Jason Kottke, here’s an interview with one of the internet’s best-known renaissance bloggers.)

The Sunday Post for February 11, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

My Own Alternate Universe

Kristen Peterson’s piece on working at a convenience store in Las Vegas is a rare example of the “I took a low-paid job” essay that’s thoughtful and respectful — the viewpoint of a resident of the job, not a tourist.

Gas stations are convenience stores, a title that’s taken literally by customers who need to be somewhere else five minutes ago. Every emotion is on display here. They’re vulnerable, captive to our abilities, bound to expectations that don’t always play out as smoothly as expected. All you do is ask a customer to reswipe their card and you’d think from their expression that you just told them their best friend has drained their bank account. Bewilderment and anger collide in their minds as they stare at you.

I Spent Two Years Trying to Fix the Gender Imbalance in My Stories

My favorite phrase from Ed Yong’s detailed account of his two-year project to balance representation of men and women among the sources for his reporting? “Anyone can do this.” If you’re looking for a how-to, this is a great place to start — and excellent debunking of the standard-issue reasons not to.

We don’t contact the usual suspects because we’ve made some objective assessment of their worth, but because they were the easiest people to contact. We knew their names. They topped a Google search. Other journalists had contacted them. They had reputations, but they accrued those reputations in a world where women are systematically disadvantaged compared to men.

Maybe There’s Nothing Natural About Motherhood

It must be exhausting, supporting a collapsing ideological industry put in place to protect your power and privilege on the basis of what other people do with their bodies. I so very much hope it is exhausting, and worse. Here’s the fabulous Leni Zumas on the politics of conception and who really has skin in the game.

In the first draft of this essay, I described Denfeld as “the mom of three adopted kids.” The word “adopted” here may seem neutral — purely descriptive — but is it? The fact of their being adopted follows soon enough. I deleted it from the introductory line because, once I thought about it, it seemed to reinforce a pecking order in which one’s biological children are standard and need no explanation.

Historically, who has benefited most from appeals to what is “natural,” “normal,” “as God intended”?

White people. Abled people. Rich people. Cishet men.

How Not to Die in America

Molly Osberg inhaled the wrong kind of bacteria and watched her world fall apart — “watched,” in this case, meaning “lived through in an nightmare blur of medically induced coma, emergency surgery, and negotiations with the health care system about whether she was too expensive to save.” Read it, then read the short piece she published a week after the original ran, with stories from people across the country of the hopelessness of America’s health care system.

Sherry Glied, the dean of New York University’s school of public service, put it a little more bluntly: Under even the lowest Affordable Care Act tier, she says, I’d be paying the out-of-pocket maximum — a little over $6,000 — and perhaps I’d be limited to in-network doctors. (The hospital I visited has maintained a relationship with an Affordable Care Act-affiliated insurance provider since 2014.) But depending on an individual hospital’s policy, and my credit score, and where I happened to land, whisking me to a second hospital with a dedicated lung surgeon to be treated by some of the country’s best infectious disease doctors might have appeared to be more trouble than it was worth.

The Sunday Post for February 4, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Hello, Goodbye

Jessica Mooney, talking about loss and inevitability, translates the small details of her experience into something lyrical, heartbreaking, and breathtaking.

I don’t know how to say what I mean. As a kid, I mixed up the words for things. Cat, I’d say, pointing at an alarm clock. Taxonomy remains mysterious. Walking around my neighborhood, I don’t know the names of things. Sinister witch-fingered bramble. Orange thing I want to call persimmon. The part of the foot that keeps me upright. The sinewy blue veins under the tongue. How do I not know the basic recipe for standing and speaking?

I love you. I wonder if I hear the words in the same place I hold my missing father. My brain’s translation: goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.

To Be, or Not to Be

Masha Gessen, a citizen of and outsider in both the United States and Russia, asks what choice (of home, of gender, of passion, of person — of who to be, and of what to say and do) means in a totalitarian regime. For example, the one into which we’re rapidly sliding …

Choice is a great burden. The call to invent one’s life, and to do it continuously, can sound unendurable. Totalitarian regimes aim to stamp out the possibility of choice, but what aspiring autocrats do is promise to relieve one of the need to choose. This is the promise of “Make America Great Again” — it conjures the allure of an imaginary past in which one was free not to choose.

The Unabashed Beauty of Jason Brown on Ice

Your eyes might try to glance past this piece on ice-skating from the New York Times Olympics special, especially with the Tonya Harding media resurrection blaring from screen and page. Don’t let them: Patricia Lockwood’s take on figure skater Jason Brown is sympathetic and fascinating, capturing what is loveable, changeable, and eternal(ish) about the sport.

“Does ‘Riverdance’ bang?” you ask yourself uneasily. “ ‘Riverdance’ might actually bang.” Suddenly, here come the goose bumps. The elasticity of his Russian splits belongs to ballet; his flexibility is less like rubber bands than ribbons. His spins are so beautiful that they look as if they might at any moment exit his body completely and go floating off like the flowers in “Fantasia.” And running alongside the joy is something grave, which seems to me to be respect for the gift.

Him Too? How Arthur Miller Smeared Marilyn Monroe and Invented the Myth of the Male Witch Hunt.

The accusation “witch hunt” is a favorite weapon for powerful men seeking to silence the #metoo movement. For another powerful, fearful man, says Maria Dahvana Headley, it was a way to silence — on the page, if not in life — a woman who asked for more consideration than he wanted to give.

Women, unless they are very devout and very old, The Crucible tells us, are unreliable and changeable. They’re jealous. They’re vengeful. They’re confused about sex and about love. They might, given very little provocation, ruin the life of a good man, and everything else in the world too.

Miller wrote it that way for a reason.

The cult of Mary Beard

Charlotte Higgins’s profile of Mary Beard is full of toothsome details and cursing. Here’s how one woman became a celebrity scholar more or less by not giving a single fuck.

Her career stands, in a way, as a corrective to the notion that life runs a smooth, logical path. “It’s a lesson to all of those guys – some of whom are my mates,” she said, remembering the colleagues who once whispered that she had squandered her talent. “I now think: ‘Up yours. Up yours, actually.’ Because people’s careers go in very different trajectories and at very different speeds. Some people get lapped after an early sprint.” She added softly, with a wicked grin: “I know who you are, boys.”

The Sunday Post for January 28, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

How I stopped being ashamed of my EBT card

In this personal essay about the social stigma (and social anxiety) associated with using food stamps, Janelle Harris deftly de-others people who rely on public assistance to feed themselves and their families.

I built a career as a staff writer and editor that didn’t require me to work the same tiring hours in the same factory conditions that my mama did, and still does. I had all the tools I needed to live a life that — if it couldn’t be sleek and sexy like a Maserati — could at least be functional and dependable like a Jeep.

In 2012, when I was fired in an abrupt mass layoff from a job that was supposed to be reliable and steady, I decided to make a full-time pursuit of the freelance writing I’d been doing on the side for years. I knew I was taking a risk, and I was prepared for lean times. As a young single mom, I’d struggled financially through all of my adult years anyway. But I never considered that the trade-off for chasing a slow-materializing dream would be abject poverty.

The female price of male pleasure

In response to the backlash against “Grace,” the young woman who spent a more-than-uncomfortable evening with Aziz Ansari, and to Andrew Sullivan’s “testosterone defense,” Lili Loofbourow talks bluntly about bad sex. Can we not distinguish between sexual assault and sexual bullying and still reject both?

One side effect of teaching one gender to outsource its pleasure to a third party (and endure a lot of discomfort in the process) is that they're going to be poor analysts of their own discomfort, which they have been persistently taught to ignore.

In a world where women are co-equal partners in sexual pleasure, of course it makes sense to expect that a woman would leave the moment something was done to her that she didn't like.

That is not the world we live in.

When ‘Gentrification’ Isn’t About Housing

Gentrification happens in waves of displacement; even the “virtuous” wave of artists and writers who make a neighborhood cool are pushing something else aside. Willy Staley has cautionary words for the affluent gentrifiers who push aside the artists — and who think their castles are built on rock.

New York’s skyline is erupting with buildings like these — stacks of cash-stuffed mattresses teetering in the wind. And The Times reported last year that the West Village’s Bleecker Street had fallen victim to “high-rent blight,” with commercial space becoming so expensive ($45,000 a month) that even Marc Jacobs couldn’t keep his stores open; shops that once catered to the wealthy now sit empty, waiting for a tenant who can foot the bill. When the heist is done and it’s time to split the loot, capital snuffs out culture.

Searching for an Alzheimer’s cure while my father slips away

Documenting his father’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease, Peter Savodnik writes about how the disease devastated his own memories.

Madness is the nub of it. In the beginning, everyone — the patient and the people who love the patient — goes a little crazy. It’s only later, after you begin to see things better — not through the prism of denial or hope, but through statistics — that you realise none of those pills are likely to accomplish anything; that garden therapy and watercolour therapy cannot, in fact, heal damaged tissue; that the numbers cannot be spun. You are in a darkened room without doors or windows.

The Sunday Post for January 21, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Awl and the Hairpin’s Best Stories, Remembered by Their Writers

If you don’t get any farther in today’s Post than this “best of” the Awl and the Hairpin, selected by writers and editors from both blogs, that’s okay. I almost stopped there, too. Mixed in with dozens of links to hilarious, moving, smart, offbeat writing are elegies for the sunsetting sites. Some are nostalgic; others are righteously angry — Sam Biddle’s, for example.

DCist, the first place that ever published something I wrote, was recently killed by a spiteful billionaire. Gawker, the first place that ever paid me to write, suffered the same fate about a year earlier. Now the Awl, the first website that took a chance on publishing me when I was just some dipshit recent college grad (I am now a dipshit 31-year-old) is dead, not directly at the hands of a billionaire, but in part by the stupid, fucked-up publishing ecosystem that tech billionaires have helped build. I guess the lesson here is try to be a billionaire if you can.

In The Midst Of #MeToo, What Type Of Man Do You Want To Be?

On the anniversary of the Women’s March, Andrew Sullivan wrote that being an asshole is a biological imperative. Ijeoma Oluo did not write a rebuttal, but her recent essay on male choice might as well be one.

As I watch countless men (and sadly, quite a few women) jump to the defense of other men who have been outed for their coercive, demeaning, and abusive behavior towards women; as I watch them debate the fine points of whether or not a woman said no loud enough, whether her “I’m not comfortable” was strong enough, whether she was at fault for being mistreated by not yelling, or hitting, or running — I want to ask them all this question: Is this the type of man you want to be?

Sudden urge to put Sullivan in a room with Oluo and wait for her to come out alone. Sudden, better urge to put Sullivan in a room with James Damore and lock the door forever.

The diabolical genius of the baby advice industry

Oliver Burkeman’s essay on books that teach parents how to rear their children is blood-curdling. The entire genre seems based on the vulnerability of new parents who are, seemingly, a desperate and wild-eyed lot, all-too-easy to convince that one misstep will ruin your child for life. Thank heavens cat and dog people are free of any such neuroticism …

What I didn’t yet understand was the diabolical genius of the baby-advice industry, which targets people at their most sleep-deprived, at the beginning of what will surely be the weightiest responsibility of their lives, and suggests that maybe, just maybe, between the covers of this book, lies the morsel of information that will make the difference between their baby’s flourishing or floundering. The brilliance of this system is that it works on the most sceptical readers, too, because you don’t need to believe it’s likely such a morsel actually exists. You need only think it likely enough to justify spending another £10.99 on, oh, you know, the entire future happiness of your child, just in case.

Too Much Music: A Failed Experiment In Dedicated Listening

James Jackson Toth’s 2017 resolution — listen to a single album, and only that album, for every week of the year — died quickly and amusingly. But his take on how the internet has changed his relationship to music, with implied parallels to the problem of curating and consuming words, is interesting. And yes: algorithms can be magical, but I still like humans best.

Missing from a larger discussion is the radical idea that maybe it is the consumers who are being done the greatest disservice, and that this access-bonanza may be cheapening the listening experience by transforming fans into file clerks and experts into dilettantes. I don't want my musical discoveries dictated by a series of intuitive algorithms any more than I want to experience Jamaica via an all-inclusive trip to Sandals.

The Things That Come to Those Who Wait

The queue, as considered by Jamie Lauren Keiles, is an engine of desire and a microcosm of social hierarchy, competition, and collaboration. A gently serious piece about mostly lighthearted things — cronuts, iPhones, and sneakers — and how we give them value by our willingness to wait.

I’m left to keep up with the latest desserts through the Instagram posts of a random teen I’ve followed online for the last three years. This past summer, she visited New York and waited in line at a place called Dō, a “confection” shop near NYU that sells raw cookie dough in spoonable cups. A few weeks ago, I visited the shop, hoping to enjoy the society of its line and try its pasteurized (though questionable) product. But arriving at the shop on a weekday afternoon, the line I sought was nowhere to be found. Two French tourists dawdled out front, enjoying their bowls of uncooked dessert. I looked through the window at the empty café. It felt pointless to spend the $4 without waiting.

The Sunday Post for January 14, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

A journey through a land of extreme poverty: welcome to America

The Guardian’s Ed Pilkington spent two weeks walking America up and down with Prof. Philip Alston, UN monitor for extreme poverty and human rights, documenting what it’s like to be poor in this country. The article is a little long in the tooth (published all the way back in December 2017!) but too fitting to miss this week, too strong a reminder that poverty and despair are anything but alien in this Great (cough) Nation of ours — and more important, at whose door to lay the blame.

Think of it as payback time. As the UN special rapporteur himself put it: "Washington is very keen for me to point out the poverty and human rights failings in other countries. This time I’m in the US."

Alternate take: Electric Literature’s roundup of books by writers from the countries Donald Trump most recently targeted with his racist, anti-human, dull-minded bullying.

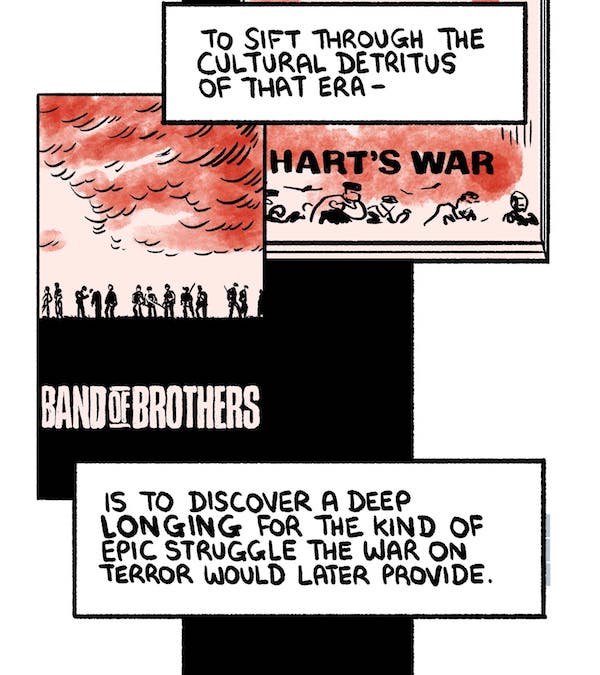

The Good War

I once studied with a man who fought in World War II — a Coleridge contrarian, a comic book writer, a quiz show winner, and a man who, captured at the Battle of the Bulge, led a lecture series in the camp where he was held to keep himself and the other prisoners sane. Watching Saving Private Ryan, he said, was almost impossible for two reasons: because the opening scene brought his memories of battle back too vividly; and because the jingoistic patriotism of the movie was so opposed to his own complicated feelings about the war and America’s role in it.

Mike Dawson and Chris Hayes have a brilliant graphic essay in The Nib against lionizing the Greatest Generation and the war they fought — against knitting those stories into a cover under which we hide injustice and cruelty and smother dissent. I know at least one member of that generation who would have heartily agreed with everything they have to say.

I Made the Pizza Cinnamon Rolls from Mario Batali’s Sexual Misconduct Apology Letter

In this piece that’s already been read by every human on the internet, but that I bet you’ll read again because it’s just that good, Geraldine DeRuiter skewers Mario Batali, bad apologies, and the patriarchy as a whole. While baking cinnamon rolls from scratch. There’s not an imperfect line in the entire damn thing.

I find myself fluctuating between apathy and anger as I try to follow Batali’s recipe, which is sparse on details. The base of the rolls is pizza dough — Batali notes that you can either buy it, or use his recipe to make your own.

I make my own, because I’m a woman, and for us there are no fucking shortcuts. We spend 25 years working our asses off to be the most qualified Presidential candidate in U.S. history and we get beaten out by a sexual deviant who likely needs to call the front desk for help when he’s trying to order pornos in his hotel room.

Donald Trump is President, so I’m making the goddamn dough by scratch.

Letter to My Younger Self

And finally! What do I love as much as baked goods? Sports. I own t-shirts dedicated to my passion for the entire spectrum, from golf to water polo. Okay, it’s one t-shirt, and it’s a bit snarky, and I’m sorry, I know it’s a personal failing but I’ve tried and I just can’t.

Nevertheless, I loved Quentin Richardson’s letter to the basketball player as a young man, especially because what it celebrates is not being the best, but simply being good enough to give the best a run for their money. I’d be happy with that. I think we all should be.

If you’d rather not be inspired in a miraculously un-sappy way, read this other thing about meeting your past in a dark alley: Matt Gemmel on finding his own suicide note years later.

But first read this.

You gotta be a dog to come out of Chicago. I mean, remember in the third grade when that kid stole your Hostess doughnut right off your lunch tray?

You could have just accepted it.

I mean, it was just a doughnut. The plain powder one.

But what did you do? You got up, snatched the doughnut right out of his hands and punched him with the damn doughnut. You gave that dude a doughnut-punch. Powder all up in his hair and everything.

It wasn’t about the doughnut, man. It was about the principle.

The Sunday Post for January 7, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Child Bride

Daniel Wallace’s mother had a favorite story about herself, one that was believable, but only just. Turns out it was also true, but only sort of. This is a kickass family detective tale and a masterclass in how people construct the stories they tell about themselve — true, false, and in between.

Now, I don’t know what else was made up, or if all of it was, or why my mother needed this fictional creation of self, of a controversial and even tragic past that never happened. Maybe she just loved how the story, like a car wreck, got your attention and made it impossible to look away. The sex part, of course, she loved. And the fact that it was against the law, even in Alabama, only made it better. She lied about her age to the judge and got away with it, and she loved that. The judge never even asked to see proof. She loved that, too. Apparently no one asked to see proof of anything, ever. Until I did.

Bussed out

The idea of offering people without a home a free bus ride to the city of their choice — a city with a lower cost of living, or where a supportive family waits — is alluring. But those are best cases, especially when accepting that ticket means promising never to return (let’s talk about consent in the context of being homeless, jobless, and entirely reliant on broken social systems, maybe?).

The Guardian spent eighteen months gathering data and stories from homeless relocation programs in the United States. It’d be ugly to call this massive state-to-state migration of the displaced a game of hot potato, but not as ugly as the reality itself.

Officials currently involved in running programs in Denver, Jacksonville, and Salt Lake City all told the Guardian they saw them as cost-effective programs that delivered their cities value for money by reducing the numbers living on their streets.

Yet it appears bussing schemes are also being used to give a misleading impression about the extent to which cities are actually solving homelessness.

When San Francisco, for example, reports on the number of people “exiting” homelessness, it includes the tally of people who are put on a bus and relocated elsewhere in the country. It turns out that almost half of the 7,000 homeless people San Francisco claims to have helped lift out of homelessness in the period of 2013-16 were simply given one-way tickets out of the city.

Trashed: Inside the Deadly World of Private Garbage Collection

Residential trash collection is a dirty job, but commercial trash collection is a dirty job. Kiera Feldman investigates how poor regulation and private-sector competition have created what amounts to a war zone for garbage collectors who serve businesses in New York. It’s a dangerous, poorly regulated, and poorly compensated profession — for the people driving the trucks and lifting more than 20 tons of garbage in a shift. For the cartels and unions who’ve run the industry, it’s a cash cow. Note that the anecdote below is from 1993.

Controlled primarily by the Gambino and Genovese crime families, four trade waste associations enforced the property-rights system — the cartel — using extortion, threats and violence. Favored tactics involved baseball bats, firebombing garbage trucks and the occasional murder. When Browning-Ferris Industries, a major national waste company, tried to enter the market in 1993, an executive found the severed head of a dog on his doorstep one morning. A note was stuffed into its mouth: “Welcome to New York.”

The Sunday Post for December 31, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

By an accident of timing, the Sunday Post has the last word on 2017 at the Seattle Review of Books.

When I agreed to collate this weekly list, it was just after Donald Trump’s election; the news cycle hadn’t yet shifted into something past lightspeed. Truth was still truth, more or less, and powerful men weren’t monsters, or at least we weren’t yet saying so out loud. We knew that Donald Trump was a racist and that his election represented something ugly embedded in this country. We didn’t understand — those of us who had the privilege not to already live and breathe it — how ugly and how deep.

As happens after a visceral blow, we were numb for a while, huddled under shock blankets and waiting for the pain to hit.

Then it did hit, hard. And writing on the internet became a firestorm of Trump-centered emotion and analysis: grief and fury, resignation and defiance, reflection and contention. Much of that writing is stunning in its depth and force.

And yet, and brilliantly, people still committed millions of words and images to simply celebrating the oddity and beauty of the world.

And yet, and brilliantly, people still committed millions of words and images to simply talking about things like books.

By treating words and ideas and books as if they matter, these writers ensure that words and ideas and books continue to do so.

So: Usually the Post covers writing that happens off the site. But I’m ceding the last word of 2017 (here at SRoB, at least) to the reviewers, poets, artists, and essayists who wrote about books for the Seattle Review of Books this year. Each of them, in their own way, transformed the fire around us — took the heat, and turned it back around.

A year in reviews

Robert Lashley wrote eloquently and with passion about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power and showed us the thoughtful, personal, eloquent book obscured behind cheap shots and hot takes.

Sophia Shalmiyev’s review of Eileen Myles’s Afterglow was breathless and reckless and startling and perfect.

Donna Miscolta wrote several pieces for us this year, but her essay on the language of rape and M. Evelina Galang’s Lolas’ House is the one that left us speechless, which believe me is not easy to do.

Kelly Froh and Siolo Thompson reviewed books by drawing comics, which is maybe the coolest thing ever.

Contrariwise, Colleen Louise Barry and Jessica Mooney reviewed comics by writing words. Both of their pieces are standouts: Barry’s review of Jason T. Miles’s Lightning Snake adeptly captures the book’s disorienting disjointedness. The opening to Mooney’s review of Kristen Radtke’s Imagine Wanting Only This is heartwrenching, and her exploration of why we’re drawn to decaying things is perceptive, empathetic, and smart, smart, smart.

Nick Cassella, in his review of Richard Reeves’s Dream Hoarders, and Jonathan Hiskes, covering Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement, tackled some of the terrifyingly large social and environmental issues of this year (and unfortunately, but unquestionably, the year ahead).

Samuel Filby looked at Maged Zaher’s Opting Out through the lens of Richard Rorty’s Philosophy as Poetry through the lens of Socrates and Derrida. A knowledgeable and wide-ranging brain-bender of a review.

“If you have never been close to death, then this book is probably not for you.” That’s Dujie Tahat on The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, reminding us that poetry is in no way distant or distinct from real life, and pushing hard on our assumptions about the Black Lives Matter movement as he does it.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore interviewed Anastacia-Reneé about violence, injustice, and our home city. Ivan Schneider interviewed David Shields, then wrote him a long letter about talking dogs.

And Anca Szilágyi, whose Daughters of the Air was just released, explained why we’ve all been thinking about translation in the wrong way — in an essay that includes one of my favorite lines of the year, and perhaps the best possible close to 2017: “To all this I say: poppycock.”

A year in verse

The fact that our year in poetry started with battle, with Elisa Chavez’s “Revenge” (“rest assured,/anxious America, you brought your fists to a glitter fight”), and ended in a hot bath, with Sarah Jones’s “When I finally get that claw-footed tub” (“the heat a rising redemption/misty and heaven-bound”), makes me gleeful — they’re the perfect bookends (sorry, couldn’t resist).

This year the site was graced by an incredible range of Poets in Residence: in addition to Chavez and Jones, JT Stewart, Jamaica Baldwin, Joan Swift (posthumously), Oliver de la Paz, Tammy Robacker, Kelli Russell Agodon, Daemond Arrindell, Esther Altshul Helfgott, Kary Wayson, and Emily Bedard. If you haven’t been following the Tuesday poem, top off your cup and catch up now.

A year in columns

Our columnists have a regular platform to talk about what they love — explain why it matters, and show us how the world looks through its lens, even when that world is run, seemingly, by a madman with bad hair.

Nisi Shawl’s Future Alternative Past is a masterclass on SFFH. Her knowledge of the genre is comprehensive, and she approaches it with a completely fresh critical lens and a fine eye for relevance. See, for example, her column on fat positivity in science fiction.

Olivia Waite’s Kissing Books touches on race and feminism and socioeconomic issues — all the hard, smart ideas that romance novels are supposed to not contain but do. And her takedown of Robert Gottlieb was epically excellent.

Daneet Steffens’s Criminal Fiction is a monthly reminder that reading is a pleasure. The joy she takes in what she reads is evident in every capsule review and interview.

- Whoever your favorite author may be, you’ll love them a bit more after Christine Marie Larsen captures them in a portrait. (For me, it's this one of G. Willow Wilson.) Her talent for conveying the kindness, compassion, and humor of her subjects is very welcome in these angry times.

Two new columnists started sharing their pen-and-ink perspective on the world at SRoB this year: Aaron Bagley’s Dream Comics are charming and odd and full of import; this one is about whales. Clare Johnson’s Post-It Note Art is quiet and personal and expressive far beyond the boundaries of a three-by-three square.

Nobody addresses humanity’s relationship with the written word, and all the shame and social awkwardness and anxiety it provokes, as regularly and accurately as Cienna Madrid in the Help Desk.

Oh, right. Martin and Paul.

- Did you know co-founder Paul Constant likes to walk? He does. He walks and walks and walks. His review of Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves talks about why, with characteristic clarity and piercing lyricism.

- Did you know co-founder Martin McClellan was in a band? He was. For the Thanksgiving essay this year (yes, that’s a thing, and so is the Christmas ghost story), he talked about a country earwormed by Donald Trump. And then he gave us a playlist to survive to.

The Sunday Post for December 24, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Comings and Goings

I read Donna Miscolta’s essay about her Uncle Dondey's funeral, and immediately I want to read it again, each time. Miscolta (a regular reviewer for the Seattle Review of Books) is a direct writer, but never dull, an emotional writer but never sentimental. This piece summons love and grief without ever saying their names; Miscolta simply shows them to us, and we know what they are, because she does.

When the last la la's of the song fade, people start to leave. Rosalva, my eighty-six-year-old aunt wobbles across the grass on heels, a niece or nephew always within range should she topple in any direction. Later in the car, she complains about the uneven ground at cemeteries, the perils it poses to innocent mourners. "I was walking just like . . . " she pauses, searching for a proper analogy. "I was walking just like a little old lady," she says.

I pat her knee. I watch her change out of her heels into soft black moccasins. The flesh on her tiny bird legs is crinkly as tissue paper and I wonder if there will be a sound if I touch her skin.

An Intimate History of America

Clint Smith visited the National Museum of African History and Culture with his grandfather, who, Smith says in a series of tweets about how the resulting essay was developed, "never thought he’d see a museum like it in his lifetime." The experience provides a line of continuity from the past that reveals the present in a clear and harsh, but truthful, light.

We made our way through the exhibitions that document the state-sanctioned violence black people experienced over the course of generations, pausing to study the images and take in their explanations: How, even after the Civil War, the Black Codes in South Carolina made it so that grown men had to get written permission from white employers simply to be able to walk down the street in peace. How in Louisiana a black woman’s body, by law, was not her own. How in Mississippi an interracial marriage would put a noose around your neck the moment the vows left your lips. The history of racial violence in our country is both omnipresent and unspoken. It is a smog that surrounds us that few will admit is there. But to walk through these early exhibitions was to be told that the smog is not your imagination — my imagination — that it is real, regardless of how vehemently some will deny it.

After Sebald

Celebrity book designer Peter Mendelsund on W. G. Sebald, the curious history of book jackets, and the mysterious interaction between authors, books, and readers. Splendidly wandering and thoughtful — a classic essay in style — and a chance to use the term "celebrity book designer," a Sunday Post first.

It then occurred to me that my own book covers, seen in aggregate, might be said to form a sort of diary as well — my diary — as these covers are, to some extent, artifacts of my own unique visual obsessions. The more I considered my work in light of this idea of a "diary," the more I began to see that there are two facets of my job — first, my own self-expression, and then second, in direct contradiction to this first idea: the mandate to understand, inhabit, and visually translate an author’s unique vision. But then I thought, aren’t these mutually contradictory vectors also in play when we read? Don’t we imagine an author’s world using the most personal of materials, our own imaginations and memories, and yet don’t we also attempt to maintain some fidelity to an author’s prompts? I had written a book on reading last year, and only now, on the threadbare floor of this bookshop did I realize that perhaps I had given short shrift to this idea of a mutual space, shared between author and reader.

Silicon Valley Is Turning Into Its Own Worst Fear

Ted Chiang writes something pretty rare — truly surprising, not just good or inventive, but surprising, science fiction. It’s outright terrifying to read his brilliantly sideways take on artificial intelligence in our not-science-fictional current reality.

I used to find it odd that these hypothetical AIs were supposed to be smart enough to solve problems that no human could, yet they were incapable of doing something most every adult has done: taking a step back and asking whether their current course of action is really a good idea. Then I realized that we are already surrounded by machines that demonstrate a complete lack of insight, we just call them corporations.

A critical analysis of Bob Dylan's Christmas lights

I wasn't expecting a whimsical piece about Bob Dylan's sparse and eccentric holiday decor to pose an ethical dilemma, but in 2017, nothing is safe or sacred. When a media company (yet another) is under the microscope because of accusations of harassment or assault, do you refuse to provide a signal boost for its writers, and by extension for the company itself? Does the decision depend on the company's response, and how quick and how likely and how thorough change may be?

At Vice, Merrill Markoe has nailed exactly what I'd expect Bob Dylan's light display to read like. Meanwhile, the New York Times reports on sexual harassment at Vice Media. Markoe's piece is charming; Vice is a hot mess. Happy holidays, and may this year pass quickly so we can get to work on whatever 2018 will bring.

A meticulous examination of this year's lighting configuration reveals the Gordian network of torments and rage roiling within this legendary artist who remains arguably our nation’s best interpreter of the zeitgeist. As usual, he has seized on this opportunity to comment upon the uniquely dangerous political crisis in which we now find ourselves.

The Sunday Post for December 17, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Case Against Reading Everything

It’s easy to win an argument if you’re the only one in it — a privilege I’m claiming, I guess, just as much as Jason Guriel does in this essay urging that we read with passion, and only what we’re passionate about.

I’m all in favor of diving for the bottom with a favorite author. But for god’s sake yes read widely too. Read with intention, and then with abandon. Read what delights you, then read what unsettles, what angers. Read what bores you — what the hell, for the discipline if nothing else. Don’t leave it to someone else to map the vast and beautiful wilderness of ideas on your behalf. That way lies, if not madness, at the very least Brietbart News.

The call to “read widely” is a failure to make judgments. It disperses our attention across an ever-increasing black hole of mostly undeserving books. Whatever else you do, you should not be reading the many, many new releases of middling poetry and fiction that will be vying for your attention over the next year or so out of some obligation to submit your ear to a variety of voices. Leave that to the editors of Canada’s few newspaper book sections, which often resemble arm’s-length marketing departments for publishers. Leave that to the dubious figure of the “arts journalist.”

On Not Going Home

This is the time of year when many of us do, or try to. For fellow wanderers who will soon walk off of a plane and into a once-familiar landscape, an uncanny valley of memory and emotion, here’s a gorgeous piece by James Wood about exile, homesickness, and the lasting contrail of early choices.

When I left this country 18 years ago, I didn’t know how strangely departure would obliterate return: how could I have done? It’s one of time’s lessons, and can only be learned temporally. What is peculiar, even a little bitter, about living for so many years away from the country of my birth, is the slow revelation that I made a large choice a long time ago that did not resemble a large choice at the time; that it has taken years for me to see this; and that this process of retrospective comprehension in fact constitutes a life — is indeed how life is lived. Freud has a wonderful word, ‘afterwardness’, which I need to borrow, even at the cost of kidnapping it from its very different context. To think about home and the departure from home, about not going home and no longer feeling able to go home, is to be filled with a remarkable sense of ‘afterwardness’: it is too late to do anything about it now, and too late to know what should have been done. And that may be all right.

What I Learned While Staring at Neil Young’s Flannel Shirts

Amanda Petrusich writes briefly and charmingly about exploring a collection of Neil Young’s possessions intended for auction.

The narratives offered by objects are usually faulty — no one has ever said that used microphone preamplifiers are a window to the soul — but these pieces can nonetheless feel intimate and revelatory as we behold them, as if there were ghosts to be coaxed from these machines. Besides, actually knowing (and being known to) another consciousness can be exhausting. Who among us has not wanted to give up and say, “Christ, just look at my paperbacks”? Neil Young never unwrapped his VHS copy of “Mastering the Theremin.” Sometimes, we all bite off more than we can chew.

Spies, Dossiers, and the Insane Lengths Restaurants Go to Track and Influence Food Critics

This is so awful and yet so delightful. Jessica Sidman gives us an inside look at how top-flight restaurants engineer a perfect dining experience for restaurant reviewers, gaming the system to achieve the highest possible grade. While the press at large struggles to maintain any sort of influence in this insane political environment, some of its members have matters well in hand when it comes to a good night out.

At one point, Sietsema noticed a table to his right filled by a smartly dressed couple having the best time of their lives. Hundreds of meals later, Sietsema still remembers how the blond woman kept looking over and smiling. Le Diplomate had purposely seated regulars who it knew would be having a good time within the critic’s vicinity.

Managers were equally intentional about who took Sietsema’s order, ran his food to the table, and bussed the dishes. The best server — a charming Moroccan guy who trained other staff and was known for being extremely knowledgeable and polished — saw to Sietsema’s group and maybe one other table. Actual servers with food-running experience took over for the regular runners and bussers. Sietsema noted a lot of suits stopping by.

The bar staff was also sweating the details. When the group started with a round of cocktails, the bar manager made duplicates of each and sent out the prettier versions. The wine director personally poured a bottle of Domaine Cros Minervois Vieilles Vignes 2000.

Back in the kitchen, chefs prepared two foie gras parfaits, two steak frites — two of everything Sietsema’s table ordered. The nicer-looking plate was sent out, while at least four senior staff sampled the duplicate to reassure themselves that nothing tasted amiss.

To Unlock the Brain’s Mysteries, Purée It

Ferris Jabr’s profile of neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel is packed end to end with surprise and delight, reflecting what seem to be the hallmarks of Herculano-Houzel’s career: curiosity, irreverence for conventional wisdom, and a willingness to explore deeply messy ideas en route to knowledge.

She began experimenting with rat brains, freezing them in liquid nitrogen, then puréeing them with an immersion blender; her initial attempts sent chunks of crystallized neural tissue flying all around the lab. Next she tried pickling rodent brains in formaldehyde, which forms chemical bridges between proteins, strengthening the membranes of the nuclei. After cutting the toughened brains into little pieces, she mashed them up with an industrial-strength soap in a glass mortar and pestle. The process dissolved all biological matter except the nuclei, reducing a brain to several vials of free-floating nuclei suspended in liquid the color of unfiltered apple juice.

The Sunday Post for December 10, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Libya's Slave Trade Didn't Appear Out of Thin Air

You should read this piece by friend-of-SRoB Rahawa Haile multiple times (as I just have), and you should also trace each link, each video, and each photo in Haile’s footsteps, looking with careful attention to see what she saw. Haile effectively documents the connection between Libya’s slave trade, immigration policies worldwide, and racism. Throughout she drags the reader’s focus back to small moments in her research where she connected with another human’s suffering. It’s deeply unsettling: we’re familiar with how journalists write about terrible things, and we know how to take it — how to digest their words safely. Haile doesn’t write to keep herself safe, or us.

In 2016, several articles spring up about slave auctions in Libya. A year later, video of an auction goes viral. Black men sold for $400. The president of the U.S. calls those who reported the story purveyors of "fake news"; a Libyan broadcaster latches onto those words to discredit the video. African leaders, European heads of state, and the United Nations feign ignorance, but they have known. And we, of the African diaspora, have done our best to tell these stories. What those in power can't name is the way the world has become too much at all times for them.

On Being Queer and Happily Single — Except When I'm Not

Brandon Taylor writes reflectively and eloquently about desire, especially navigating a kind of longing that looks quite different from what anyone else expects.

Sometimes, I say that I want to be with someone who I only have to see three or four times a week, and only to cook meals and go book shopping. I say that I want some flannel-wearing bearded man to descend from a rainy mountain in Washington State or Vermont, who smells like crushed ice and the sharp scent of pine sap, who will read Proust to me in French and drink from enamel mugs beside a firepit with me. That’s what I want. And what my friends say to me is that I want a best friend who dresses like Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, and I say, yes, probably. But the look in their eyes is rueful pity, that this is not enough.

The Consent of the Ungoverned

As accusations and resignations and firings related to sexual assault, sexual harrassment, and just plain jackass behavior continue to roll out, it's hard to pick a single essay to promote. Right now the internet is doing something the internet does really, really well (yes, those things exist): a multitude of smart, experienced, excellent thinkers and writers are analyzing, arguing, negotiating with themselves and with each other — prodding the rest of us to think harder and not be complacent in our own righteousness and sense of outrage.

This week, Ijeoma Oluo is brilliant and angry and honest, as always, in her response to her hero Al Franken's resignation. The New York Times's breakdown of how Harvey Weinstein used his power and influence to silence women he had irrevocably wronged and the men who might have spoken up for them is chilling. Lucinda Franks, also in the NYT, talks with honesty and weight about revising her perception of her past — it's the other side of the male complaint that "things were different then," a side that hasn't been fully addressed. Jess Zimmerman responds to Claire Dederer's piece on "the Art of Monstrous Men" with one of her own about how gatekeepers not only determine what's good art, but what good art is. Josephine Livingstone argued with Allison Benedikt about what women will have to give up — what cherished fantasies and self-conceptions — if we continue, as we should, to walk through the door that Weinstein's accusers opened for us all.

So it's really a matter of personal taste that Laurie Penny gets top billing this week — Laurie Penny, our resident master of articulating inarticulate-able rage.

We know the world doesn’t work the way most of us want it to. We watch a bunch of badly-fitted suits stuffed with self-satisfied swagger frogmarch our nations down the road to economic calamity and climate destruction, and we try to tell ourselves that we chose this, that we have some sort of control, that there is a thing called democracy that is working more or less as it was designed to. We want to believe that some of this is our fault, because if it isn’t, then maybe we can’t do anything to stop it. This is more or less the experience of being a citizen of a notionally liberal, notionally democratic country these days. It is depressing and scary. And if we ever actually speak about it honestly we can count on being dismissed as crazy or bullied into silence, so it’s easier to swallow our rage, to bear up and make the best of things and try not to start drinking before noon every day. Being as furious as we want feels like it might be fatal, so we try not to be too angry. Or we direct our anger elsewhere. Or we turn it inwards. Or we check out altogether.

Sound familiar? That’s about how most women experience sexuality.

My Twentieth Century Evening — and Other Small Breakthroughs

It’s perfectly fair to wish the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature had gone to a writer who was nothing like Kazuo Ishiguro: a writer less expected, less established, in particular less powerful and privileged. Big prizes have muscle — muscle that could be used to shake the equilibrium of the literary mainstream, to break the vacuum seal and pull different voices into the conversation with a great whoosh of fresh air.

However, for readers who love Ishiguro and his quiet, terrifying sentences, who love Ishiguro and his quietly terrifying books — especially the ones that aren’t suited to a Merchant Ivory film — pfft on reasonable thinking: your man won. Here’s his Nobel Lecture, interesting for its insight into his process (cameo by Tom Waits!), his history, his hopes. I only wish Ishiguro had been, in addressing the imperatives for writers and readers right now, as quietly terrifying as our current political moment deserves.

So here I am, a man in my sixties, rubbing my eyes and trying to discern the outlines, out there in the mist, to this world I didn't suspect even existed until yesterday. Can I, a tired author, from an intellectually tired generation, now find the energy to look at this unfamiliar place? Do I have something left that might help to provide perspective, to bring emotional layers to the arguments, fights and wars that will come as societies struggle to adjust?

Hummingbirds Are Where Intuition Goes to Die

And now! Hummingbirds! Birds’ tongues are straight-up weird. If you pull on a flicker’s tongue, for example, the feathers on the top of their heads stand up. TRUE. (This is both difficult and rude — to the flicker — to test out in daily life, so please don’t.) Here’s another one: We thought we knew how hummingbird tongues work; turns out we were completely wrong. Also their flight style is insane, they can bend their beaks, and there’s absolutely no reason they should be able to thrive in the environments they prefer. Also science. This article by Ed Yong is pure joy.

Rico-Guevara handcrafted artificial flowers with flat glass sides, so he could film the birds’ flickering tongues with high-speed cameras. It took months to build the fake blooms, to perfect the lighting, and to train the birds to visit these strange objects. But eventually, he got what he wanted: perfectly focused footage of a hummingbird tongue, dipping into nectar. At 1,200 frames per second, “you can’t see what’s happening until you check frame by frame,” he says. But at that moment, “I knew that on my movie card was the answer. It was this amazing feeling. I had something that could potentially change what we knew, between my fingers.”

The Sunday Post for December 3, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Trapped: The Grenfell Tower Story

Tom Lamont’s account of the Grenfell Tower fire is riveting and wrenching. It’s not a political examination, but a human one, a set of interlocking stories by residents and firefighters who lived through the night. A piece like this always risks catering to looky-loos. But I think it’s worthwhile, for obvious reasons right now, to invest our attention in the implications of political decisions (regulatory, economic, and otherwise) — implications from which the politicians calling the shots are mostly exempt.

Fire from the fourth floor had reached an outside wall of the tower and then caught — unthinkably — the sheer sides of the exterior. Fat amber flames licked up Grenfell's northeastern elevation so quickly, so determinedly, that for a time firefighters stationed indoors and outdoors would have been responding to wildly different degrees of crisis. What would have seemed inside to be a manageable appliance fire was catastrophizing, outside, into the gravest threat to residential Londoners in 75 years: since the city's bombing at war. One of the first police officers to arrive at the scene would later say that "the building was melting." At least 320 people were inside. Most, like Oluwaseun Talabi, were asleep.

Ana Mardoll on Prairie Fires

With many apologies to those for whom Little House on the Prairie is a beloved childhood touchpoint, here’s Ana Mardoll’s brilliant, hilarious live-read of Prairie Fires, the new biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder. If you’re wearing rose-colored glasses, take them off now so you don’t get shards in your eyes — this woman has evidence-based smacktalk down to an art.

To no surprise whatsoever, Almanzo is now breaking homesteading rules and scamming the government. Again, I don't disapprove exactly, but I remind you this is supposed to be people who succeeded through honest hard labor.

Almanzo is being a dick to Eliza Jane but I am 100% on her side, fight me. She's going to claim her own homestead at 29 because fuck marriage and men, and that's frankly way more sympathetic than Manzo and Royal. I mean, they're all trash fires stealing land from indigenous people, but at least she hates men and I respect that.

Cormac McCarthy Returns to the Kekulé Problem

The only thing better than Cormac McCarthy offering up an apostrophe-less analysis of one of the knottiest problems in linguistics is McCarthy responding to readers’ comments and questions on the selfsame piece.

I havent read the William Burroughs book that several people mentioned in which apparently language is compared to a virus. The only Burroughs book I’ve read is Naked Lunch. One reader seemed to know that that is just what I would say. Bloody McCarthy lies about everything. Naked Lunch was supposedly so named by Jack Kerouac. When Burroughs wanted to know what it meant, Kerouac said that it was that frozen moment when everybody sees what’s on the end of the fork. Or so the story.

Mea Culpa. Kinda Sorta.

Remember how your mom taught you to apologize — straight up “I’m sorry,” not “I’m sorry you felt bad,” not “I’m sorry and here’s why it’s your fault”? Apparently not everyone got that memo from mom, even with professional PR agencies to help them. Jessica Bennett, Claire Cain Miller, Amanda Taub, and Choire Sicha of the New York Times analyze shitty responses from shitty men, media and otherwise, to accusations of harassment and assault.

These sound like the ramblings of your crazy uncle at Thanksgiving dinner.

The Sunday Post for November 26, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

What Do We Do With the Art of Monstrous Men?

This is the must-read of the week, and not just because it’s Claire Dederer, which means it’s sharp and funny and expresses anger and feelings in the most satisfyingly vulnerable-but-also-take-no-prisoners way possible. I mean, that’s a perfectly good reason to read it. We could stop there.

But also read it because it turns out that our creator-heroes don’t just have feet of clay, they have been absolutely wading through shit, and it’s spattered all of us. Now we have to deal with what that means for everything important and beautiful they made — all the important and beautiful things that became part of us — and the making of important and beautiful things at all.

The thing is, I'm not saying I'm right or wrong. But I'm the audience. And I'm just acknowledging the realities of the situation: the film Manhattan is disrupted by our knowledge of Soon-Yi; but it’s also kinda gross in its own right; and it's also got a lot of things about it that are pretty great. All these things can be true at once. Simply being told by men that Allen's history shouldn’t matter doesn’t achieve the objective of making it not matter.

What do I do about the monster? Do I have a responsibility either way? To turn away, or to overcome my biographical distaste and watch, or read, or listen?

And why does the monster make us — make me — so mad in the first place?

Wednesday Addams Is Just Another Settler

Thanksgiving — especially in the American West, a scant year after the police attack on protesters at Standing Rock (and a scant week after the largest spill yet from the Keystone Pipeline in South Dakota) — represents some of our nation’s very worst moments, all knotted up with family and tradition and community in a way we just can’t seem to tease apart. Elissa Washuta writes brilliantly about reclaiming a sense of belonging from the sticky tangle of America’s most problematic feast day.

It's been a decade since I spent a Thanksgiving with my parents. After I moved to the West Coast, the holiday wasn't important enough to me to justify the expense of a cross-country flight. For the last ten years, I've spent Thanksgiving with friends or relatives or alone. I've never liked Thanksgiving and for a while, I couldn't figure out why: I like and love my family and I like to eat. I decided it was the football, or the years of packing my body with stuffing while suffering from undiagnosed celiac disease, or the anxiety, later, of trying to avoid both gluten and the anxious shame of making others think about it. Really, though, I'm uncomfortable committing to a six-hour stretch spent with other people (even those I'm fond of), no activity planned but eating, no hiding place for me to retreat to, and no way to silence the mean critic in my head who begins analyzing my words at the two-hour mark. I dread any event that fits this description. Thanksgiving is only different because my Nativeness has let me get away with hating it.

'I Have No Idea How to Tell This Horror Story'

You’ll find this correspondence between reporter John Branch and Walter Peat, father of an NHL “enforcer” with concussion-related health and behavioral issues, nestled between headlines celebrating the sport on the hockey page on the New York Times website. It’s a short read, but a unique perspective on how badly big-money sports organizations are failing their players — a raw appeal for help that had not, at the time of publication, yet appeared.

I am at a loss of what to do, and who to turn to for help. Many night, I lose countless hours of sleep, thinking of what will happen, and am I doing the right thing. There are so many people who prefer to put a paper bag over their head and ignore the fact that Stephen or so many players suffer from these injuries. But, the injuries just don’t stop there, as the emotional, financial, and in some cases, physical injuries suffered by family members. I am living the nightmare of the movie "Concussion."

How to Get Rich Playing Video Games Online

Remember when the Seattle Police Department’s public affairs office tried using the streaming video game platform Twitch as a way to connect with the public about sensitive issues like the Charleena Lyles shooting? Here’s an insanely fascinating article by Taylor Clark about the people who make a living as Twitch personalities, sometimes playing 60 hours or more straight to build and keep an audience. That this exists at all feels crazy, much less that it’s getting professionalized in exactly the same way as any other digital marketing medium.

Perhaps the best embodiment of the effort to master Twitch is Ben Cassell, O.P.G.'s first client, who broadcasts, as CohhCarnage, from his farmhouse in North Carolina. After nearly quitting Twitch in 2013, when sixteen-hour streams weren't winning him an audience, Cassell instead dedicated himself to research. "This medium is brand new," he explained. "There's nowhere to go to see how to succeed on Twitch." So he built data-tracking software, and studied scheduling, game selection, and the market's niches: hard-core professional gamers, lighthearted jesters, "boobie streamers," histrionic yellers, baseball-cap-wearing frat bros. Based on his findings, Cassell reinvented his channel as upbeat and safe-for-work; to followers, he told me, "my channel is "Cheers.' " Every day — and he has logged more than fourteen hundred in a row, including the one on which his first child was born — he begins his stream at 8 a.m., right before Twitch's audience crests.

The Sunday Post for November 19, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.