Archives of Thursday Comics Hangover

Thursday Comics Hangover: How to attend ECCC without attending ECCC

Emerald City Comicon has long since sold out, but that doesn't mean you can't enjoy a number of (free) comics-centered celebrations around Seattle this weekend. Here are a few of the best-looking events for you to attend:

Broadway's Phoenix Comics is hosting a signing tonight from 5 to 7 pm with Seattle author G. Willow Wilson and former Batgirl writer and MotorCrush writer/artist Babs Tarr.

The fantastic free comics anthology Thick as Thieves is hosting "Thievescon" Friday night at Nii Modo on Stone Way. All sorts of great local cartoonists will be in attendance including Marie Hausauer and Sarah Ramano Diehl. This looks to be a great independent Seattle-centric mini-con.

Also on Friday night, Outsider Comics and Geek Boutique in Fremont is hosting Seattle artist Tatiana Gill as part of their artwalk celebration.

Saturday afternoon and evening, Outsider Comics is hosting a signing from cartoonist Ben Fleuter and a signing from Richard Rivera, who created something called Stabbity Bunny.

Yesterday I interviewed Jaime Hernandez, who will be doing a special signing at a party at the Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery in Georgetown on Saturday night with other cartoonists including Simon Hanselmann.

And also on Saturday night, Phoenix Comics is hosting a party to celebrate the podcast Jay + Miles X-Plain the X-Men.

And if you'd rather buy comics than socialize, Comics Dungeon in Wallingford is hosting a different sale for every day of the convention. These sales, according to the Dungeon, have "one specific goal; to try to get you to try something new!"

Thursday Comics Hangover: Politics is best served cold

Last month, Drawn and Quarterly published the new English translation of Swedish cartoonist Anneli Furmark's comic Red Winters. Though the book is set in 1970s Sweden, it feels newly relevant for a politically charged America in 2018.

Their political differences don't matter to Siv and Ulrik, but they do matter to everyone else. As the community discusses Siv's infidelity, the relationship becomes a partisan football, used to question the couple's commitment to their respective causes. The communists suspect Ulrik of selling out; neighbors wonder if Siv is about to turn radical.

Of course, every affair is political. Siv and Ulrik's decisions don't only affect them. Red Winter brilliantly displays the impact of the affair on everyone in the community by continuously changing perspectives: one chapter focuses on Siv's daughter while another centers on Ulrik's nosy roommate. Siv's husband starts to realize something is wrong. Everyone is, ultimately, a partisan.

Anyone who's lived through Seattle's endlessly glum winters will find something to recognize in Furmark's gorgeous illustrations. A cold and dark winter - snowier than here, obviously - permeates every page, and Furmark's orange-and-blue color palette perfectly portrays the whipsaw winter alternation between cozy warmth and brutal frigidity. You can feel the cold of this book in your bones.

The characters, too, are instantly recognizable in just a handful of lines. Even as they strip off layers when they head indoors and swaddle themselves in protective winter clothing when they leave the house, you always know exactly who you're looking at. Furmark's biography describes her as "One of the most important comics artists in Sweden," and Red Winter is the first full-length work to be translated into English. Let's hope it's not the last.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Passing in the night

Berger Books, the new editor-driven imprint from Portland publisher Dark Horse Comics, is something new in the world of comics. It's a bet that readers of comics actually care about editors - or even really understand what comics editors do, for that matter. But to be fair, Karen Berger is one of the most successful editors in comics history: she created DC Comics's wildly successful Vertigo line, which created the template for modern mature-readers comics.

And now that Vertigo has largely disappeared, maybe there's an underserved audience that will flock to Berger Books. I certainly hope so; based on the one book from Berger that I've read - writer Mat Johnson and artist Warren Pleece's Incognegro: Renaissance, the first issue of which published just last week - this is a line that's deserving of a very large audience.

Renaissance opens with our hero, Zane Pinchback, attending an un-segregated party in honor of a new novel about Harlem written by a white author. The publisher praises the author for "braving streets of Harlem rarely seen by white eyes," which causes all the Black eyes in the house to roll violently back in their skulls. ("Another hand for the great white warrior, back from safari," one Black partygoer blurts as he chugs on a bottle of wine.)

Johnson and Pleece elegantly set the stage here: they walk us through the party, introduce us to all the suspects, and then establish a splashy murder of a surprising victim before the book hits page 20. The tensions are high, and everyone's got a motive. Pinchback makes a great detective, as he can code himself on either side of the racial tensions surrounding the murder. I can't tell you how the book will play out, obviously, but Renaissance's first issue is a compelling beginning, and Berger's imprimatur should earn a reader's trust that the story will keep the promise made by the opening chapter.

The limits of cartoonomics

Let’s be clear: former Labor Secretary Robert B. Reich is a cartoonist, but his latest title from Seattle-based comics publisher Fantagraphics Books, Economics in Wonderland, is not a comic book. The illustrations in the book aren’t, strictly speaking, comics. They’re cartoons. Perhaps this seems like splitting hairs, but it’s an important distinction: comics involve a juxtaposition of words and illustrations, while cartoons are simply funny drawings that accompany the text without enriching the text.

Wonderland is adapted from Reich’s wonderful series of short illustrated economics lectures on YouTube. Here’s a sample:

Without the actual video of Reich drawing the cartoons, they lose something on the page. In the videos, Reich will often go back and cross out a word or a phrase he previously drew for emphasis. In the book, that word or phrase only appears crossed out, and the impact of crossing it out is lost. Basically, you could read the book without looking at a single illustration and you wouldn’t really miss anything. Which is a bummer.

At the Reading Through It Book Club at Third Place Books Seward Park last night, some of our members were frustrated with Wonderland. They weren’t sure who the book’s intended audience was; was it preaching to the choir, one member asked, or was it supposed to win over conservatives? Why didn’t Reich provide more examples of why a higher minimum wage was a good thing, say, or how more people benefit when we tax the rich at a higher rate?

Speaking as someone who has interviewed Reich and reviewed many of his books, I think some of those complaints miss the mark. Reich is interested in building an economic vocabulary for progressives, to give them an array of cohesive ideas through which they can understand and explain the world. He’s an educator first — his preferred title is “Professor Reich,” not “Secretary Reich” — and not a journalist. He is a gifted lecturer and a top-tier economic thinker, and he’s devoting his talents to explaining middle-out economics to a broad audience.

Some members of the Reading Through It Book Club, though, seemed to think that economics isn’t enough, that Democrats need to do a better job of conveying empathy and why government needs more compassion. And others thought Reich's ideas were a waste of time; one member rejected the idea of Universal Basic Income out of hand, for instance, because he said it wasn’t possible.

And then there’s the question of whether economics can get us out of this mess at all. If capitalism demands continual growth in order to be healthy, can capitalism be considered a truly sustainable system? A middle-schooler with one physics class under her belt could tell you that never-ending growth is impossible. Can we spend our way out of the mess that America has become? We were once promised that automation would create 3-day work weeks for everyone; now we’re told that automation will render millions of jobs obsolete, and we can see that technology has blurred the lines between work and personal life in some very uncomfortable ways.

A number of Reading Through It members loved Wonderland and appreciated the way it made economics — an inscrutable field to them, previously — into something that they could easily understand. I, for instance, appreciated Reich’s description of the way the Federal Reserve maintains the complicated relationship between interest rates and inflation. Throughout the book, people found clarity on matters that previously seemed too complex to understand. In that way, Reich’s talent as a teacher became clear. Everyone learned something, and we had an intense 20-minute conversation about whether Universal Basic Income is a tenable Democratic position for the 2020 elections. Not bad for a book of silly cartoons.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Milk is hell

I've been enjoying the Young Animal line of comics curated by My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way. They're a pop-up imprint published on the fringes of the DC Comics superhero properties, taking on the same rebellious-goth-teen role that Vertigo Comics did back in the 1990s. The best Young Animal books, like Mother Panic, fill in a gap left by the all-ages edict of mainstays like Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman. They're a little bit weirder, a little bit more imaginative, a lot looser.

This week saw the first issue of Milk Wars, a crossover between Young Animal comics and DC Comics. If you've ever been disgusted with the crass action-figure ballet that is the typical superhero crossover, you'll probably find something to love here.

Milk Wars is a meta-crossover pitting the weird heroes of the Doom Patrol versus the staid, conservative heroes of the DC Universe. And thanks to an intergalactic bureaucracy called Retconn, the DC Universe has been made even more conservative. Superman is a flying milkman. The other Justice League figures have been recast as the Community League of Rhode Island, a staid suburban homeowners association with superpowers.

This feels like a crossover with something to say, which is a rarity for the genre. Of course, some of that conservatism of the mainstream DC line rubs off on the Doom Patrol; while the Young Animal books are generally content to be weird without bragging about how weird they are, in this comic they're painfully self-aware.

"Some of the best people are weirdos," a Doom Patrol member says while in the middle of a fight with the godlike milkman, and the point is made. But then two panels later, she adds, "everyone's a little strange, and that's okay." Later on, someone says "maybe strange deserves a shot." There's nothing less weird than talking about how weird you are; the repetition gives off the impression of a coffee cup that reads "You Don't Have to Be Crazy to Work Here, But It Helps!"

This is probably the reason Vertigo began enforcing a concrete divider between itself and the mainstream DC superhero universe in the late 1990s. When you combine the two tones into a single book, you get something that feels a little smaller than its component parts. Milk Wars, at least, seems to recognize that flaw and builds it into the plot.

And in Milk Wars #1, you get several full-page shots of people with bizarre powers punching each other, which is the point of these whole things, right? Can there be anything more dull, anything more in direct opposition to art, than conflict for conflict's sake? And isn't there maybe a chance for some art to made out of that artlenssness?

Thursday Comics Hangover: Less talk, more rock

I enjoyed the first issue of sci-fi writer Saladin Ahmed's Black Bolt series for Marvel Comics, but I ultimately didn't continue with the book, because Black Bolt is the very definition of a one-note character. The best writing in the world couldn't make an aloof mute king with a tuning fork on his forehead a compelling protagonist. But there was so much talent in evidence in that first issue of Black Bolt that when I saw Ahmed had a new creator-owned series coming out from Boom! Studios, I was eager to give it a try.

Abbott, published for the first time yesterday, is a new series about an African-American newspaper reporter in 1972 Detroit. Elena Abbott is described in the first issue of Abbott as a "black Lois Lane," but Ahmed admits in interviews that he envisions the character as more along the lines of the cult TV show Kolchak the Night Stalker.

A tough Black journalist on the mean streets of 70s Detroit, fighting supernatural menaces? Yes, please! Abbott has all the makings of a great comic series, and artist Sami Kivelä is a revelation: he draws apartments that look lived in, and figures that have lived entire lives. It's a flat-out gorgeous book.

It's a shame, then, that the first issue of Abbott suffers from a pretty severe cass of first-issue-itis. There are a lot of word balloons here covering up Kivelä's beautiful artwork, and a lot of them could have been trimmed. The exposition flows hot and heavy, with a lot of telling and not enough showing. Early in the issue, Abbott shows up at a crime scene with her own camera. She's greeted by an older white photographer. This is their exchange:

—Holy crap, Abbott, Fred's got you taking your own pictures now? That's ridiculous. He giving you any kind of budget?

—Hello, Murray. It's not Fred. It's the higher-ups. Someone didn't care for my police brutality stories. I'm being punished.

—That's too bad. You're a good reporter, Abbott. A damn good reporter. Better than the little @#$%& I'm working with now.

—Thank you, Murray. And you're the best crime photographer in Detroit.

—Now you're just flattering me.

—Well, it is possible I'm hoping you'll tell me what the police know here, since no one else will.

This exchange desperately needs an editor. There's way too much backstory and repetition and cross-talk for the first few pages of a comic. I'd love to see Murray and Abbott's history relayed through an intimate exchange that didn't lay everything out so plainly.

As the issue carries on, Abbott starts to pick up in pace, building to a cliffhanger that really sets the premise in motion. I'm definitely coming back for the second issue. But I'm also willing to bet that the second issue of Abbott should have been the first issue; dropping the reader in the middle of the action and forcing them to figure out the story as it goes along is always preferable to explaining everything.

Thursday Comics Hangover: I'd buy that for a dollar (and fifty cents)

Last year, small press comics publisher Alterna Comics began publishing a line of cheap comics. Printed on flimsy newsprint, these books sold for $1.50 a pop — about half the price of the cheapest monthly comics published by the big two mainstream publishers.

Unfortunately, most of what I've seen from Alterna Comics hasn't blown me away. One comic, Amazing Age is clearly playing for a noxious kind of superhero nostalgia. It reads like a Marvel Comic from the 1980s with worse art — full of self-referential superhero action with no depth or consequences. The comic appeared to be designed to appeal to the grown men who remember spending $1.50 per issue on comics, and really nobody else.

But at least one of Alterna Comics's line has very much impressed me with its wicked sense of genre fun. Written by Jordan Hart and illustrated by Emmanuel Xerx Javier, the four-issue miniseries titled Doppelgänger tells the story of a bland computer programmer named Dennis who finds himself copied by an ancient, evil magical creature. The Dennisgänger takes over Dennis's suburban life, sleeping with his wife and playing role playing games with his friends.

The second issue of Doppelgänger landed yesterday, and it's everything you'd want in a second issue. The book doesn't waste any time spinning its wheels, instead launching forward into Dennis's plan to take his life back. Meanwhile, the Dennisgänger begins to assert himself in dynamic ways at Dennis's job. The two are hurtling toward each other, and it's a real pleasure to know that the storytellers aren't going to waste their readers' time in the telling of the tale.

Doppelgänger is fantastic, pulpy fun — a dark fantasy thriller that seems to be hurtling toward a conclusive ending. I'd be thrilled to buy it at three times the price. At a buck fifty an issue, I'm not sure why it's not on the bestseller charts.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Heavens to murgatroyd!

Friends, I'm going to make a bold announcement: It is quite possible that the best new series of 2018 from one of the big two "mainstream" comics publishers has already made its debut. The book in question was published last Wednesday — the first new comics day of the year — and I can't stop thinking about it.

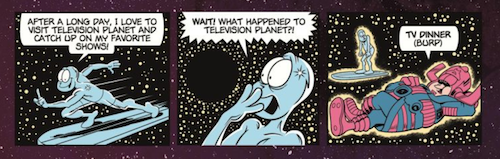

And it's a comic book based on the old Hanna Barbera character Snagglepuss. Yes, that Snagglepuss:

Written by Mark Russell and illustrated by Mike Feehan and Mark Morales, Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles is a new limited series that imagines Snagglepuss as a closeted gay playwright in the red-panic blacklist era.

This is the most literary comic I've read in ages. How literary? Dorothy Parker is a main character in the first issue. "Personally, I always admired the Algonquin Round Table, the finest assemblage of wits in American history," Snagglepuss explains to a reporter outside a play. "As a young kit growing up in rural Mississippi, they were my Knights of the Round Table. New York, my Camelot." (The reporter then looks at the reader and announces, "a young lion makes good. Only in America!")

Much like Russell's amazing Flintstones comic from 2016, what should be a one-note joke instead plays out with intelligence, wit, and a strong moral core. Russell has got to be among the finest satirists in modern American comics — admittedly, it's not a crowded field — and his compassion for the character practically throbs off the page.

Stage Left isn't afraid to poke around in the darkest corners of post-WWII America. So what if every fifth character or so is an anthropomorphized dog or cat or mouse? And who cares if those talking mammals don't wear pants? I'm not sure if the whys and hows of Snagglepuss's world will ever be explained, or if there's a single unified theory of the satire. (Are the animals in human clothes supposed to represent the naivete of 1950s America? Uh, maybe?) But at this point, I'm having so much fun with the premise that I frankly don't care.

Thursday Comics Hangover: They're good comics, Brett

I'm convinced the telecommunications network is doomed to collapse so I started making zines again! You can buy one and have it delivered to your mailbox. Old skool! #zine #comix #cartoon #drawing pic.twitter.com/mPuggYQn16

— Brett Hamil (@BrettHamil) December 18, 2017

I don't think that Seattle writer and comedian Brett Hamil would be offended if I referred to his art as amateurish. He's not looking to wow you with his hyperrealistic portraits, or his three-dimensional rendering style. No, the illustration in his cartoons are fairly primitive; they're better than I (and likely you) could draw, to be sure, but not by too much.

And that's okay. Hamil is a standup comedian, and his cartoons are strictly joke delivery systems — the quickest way for him to get a good laugh out of you in the print medium. In that regard, they work really well; they're classic gag cartoons.

Hamil has collected some of his funniest City Arts cartoons in a five dollar zine titled Subconscious Hairstyle Mirroring (and other notions), and I'm pleased to report that the strips work even better in aggregate than they did singly, as they were originally published.

Like any good gag cartoonist, Hamil works within a few formulas. He imagines absurdist magazine covers (sample Infant Magazine headline: "Object Permanence: Myth or Fact?") and creates little four-item lists of observational comedy (one of the items in "Why We've Got Swagger Today:" "Found typo in the New Yorker.")

These strips are full of the kind of laughs that come when you recognize the absurd in the familiar. Schlubby middle-aged white guys are absolutely crazy about boxer briefs, for instance, and introducing someone to your favorite barista is, in fact, a major relationship benchmark. When rendered in Hamil's no-frills style, the jokes are even funnier: there's a nice back-of-the-envelope feel that saves the strips from becoming too self-important.

Hamil claims to have assembled Hairstyle as a minicomic because he believes the internet, with its weird self-destructive social media and its lack of net neutrality, is going away. I'd almost welcome internet armageddon if it meant more physical media like this.

And I'd definitely welcome another collection of comics that highlight Hamil's more strident political side. With his passionate political commentary Hamil has become one of Seattle's most outspoken citizens — the kind of angry truth-teller that politicians loathe and activists adore.

Hairstyle generally sticks to social commentary and absurdist comedy, and that feels exactly right for a debut collection. But if Hamil published a collection of comics about Seattle's consistent failure to construct a strong municipal broadband system, for example, I'd be the first in line to slap down my five bucks. When a comedian starts speaking relentless truth to power, that's when things really start getting good.

Thursday Comics Hangover: From a roller rink to the stars

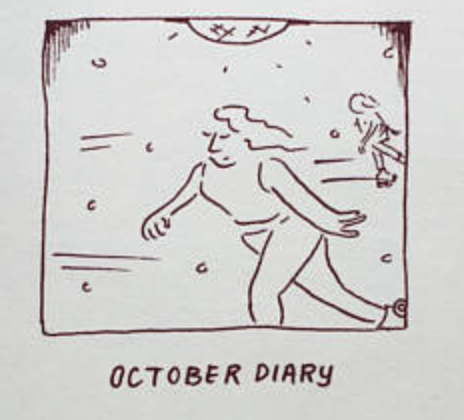

Natalie Dupille works along a wide spectrum of cartooning. Her diary comics — as seen in her most recent collection, October Diary — are sketchy and minimalist. It's remarkable the information that Dupille's cartooning can convey in with so little. Look at this image from the cover of October Diary:

Now consider how amazing it is that your eye can assess that image and immediately determine that it's set at a rollerskating rink when all you can see is exactly six motion lines, an eighth of a disco ball, a single rollerskate wheel, and a background figure. Dupille's entire head on the cover of the book is made up of exactly eight lines: one arrow of a nose, a swooping chin, a concentrating dot of a mouth, two eyes tight in concentration, and then three wavy lines marking her hair flowing in the breeze.

Some might think this rough sketch style of art is simple, but it is in fact inordinately difficult. When you draw with fewer lines, as Dupille does in her diary comics, that creates a tremendous pressure on the artist to make sure that every line is exactly the right line.

The writing in these diary comics is perfectly complementary to the art. Dupille catches a single moment in her day and rounds it out using exactly the right images. She notices how abusive guests at a dinner party behave toward the female voice coming out of an Amazon Echo speaker, for instance, or a blandly inoffensive statement at a corporate meeting can trigger memories of Donnie Darko.

These are tiny moments, but they are titanically tiny moments. They feel neat and self-contained and somehow expansive enough to swallow a reader's brain whole. One page of silent sketches of Dupille's cats and a caption reading "Sad & listening to Graceland on repeat" has somehow taken up residence in my head the way a good pop song does; I'm currently thinking of this strip six to eight times a day.

But there's a flip side to Dupille's work, on the other end of the spectrum from her sketchier comics. Her more rendered work features what appears to be watercolor, adding a delicate and vibrant life to her lines. These painted strips tend to focus on nature and science, and they demonstrate Dupille's boundless curiosity and enthusiasm for learning.

In Huckleberry Pie no.3: Selected Comics 2015-2016, Dupille lays out a two-page spread about the sex lives of banana slugs and earths, and it's a joyous, fun pair of strips. (Banana slugs, she tells us "frequently eat each other's penises after sex. No one really knows why, but we're accepting of most fetishes here in Seattle.") Another, more personal strip details the construction of a cob oven as part of Dupille's attempt to get closer to the land. Readers will find Dupille's attempts to understand the world around her to be infectious; her unabashed geekery is wildly appealing.

Total Lunarchy, a self-described "Zine About Space Dust and Other Important Extraterrestrial Matters," expands Dupille's curiosity into the chilly depths of space. Specifically, she focuses her curiosity on the clingy dust that has plagued the few astronauts we sent to walk on the moon. Lunarchy is about all the things we don't know about the moon. Specifically, she examines why static cling and magnetic fields combine to make the moon inhospitable to our attempts to set up base there.

Dupille is at the top of a very short list of cartoonists who are gifted at explaining science in a fun, approachable way. Lunarchy came out of a collaboration between Dupille and UW research associate professor Dr. Erika Harnett, and hopefully it's not the last foray Dupille will make into the sciences. The universe is complex and confusing; we could use more guides like her to illuminate the darkness with funny and informative cartoons.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Kids these days

Writer Matthew Rosenberg and artist Tyler Boss’s 5-issue crime miniseries 4 Kids Walk Into a Bank is finally available in collected form, and you need to hunt down a copy immediately. Kids has so far managed to evade mainstream acclaim somehow, but its moment will come. The book is too goddamned enthusiastic, too exuberant, to ignore.

Kids is a comic about four children who become tangled in some very adult dealings, up to and including a bank robbery. They’re relatively normal kids — maybe a little more clever than the average child, but not obnoxiously so — and so they go about a life of crime in the bumbling way that children go about anything: they only understand parts of what’s going on around them, and they laugh at inappropriate things, and they are excitable in exactly the wrong ways. While they understand that they’re in a life-or-death situation, they might not understand exactly what a life-or-death situation entails. (Four of the five issues open with fantasy sequences of the kids playing video and role-playing games, where all the consequences can be wiped away with the click of a reset button. This is no mistake.)

Rosenberg and Boss match the kids enthusiasm for enthusiasm. Rosenberg’s script is a little overbearing — it is indisputably dialogue-heavy, though the text is zippier than in your average crime comic — but it is clever and funny and the characters feel real, by which I mean they’re not always likable.

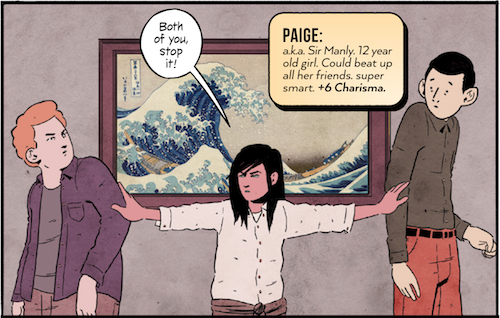

Boss’s art leans on the minimalist side of gorgeous. He’s good at stepping back and choosing just the right line to tell a character’s story. And he experiments in all sorts of fun ways. Get a load of the way he incorporates Katsushika Hokusai’s painting The Great Wave off Kanagawa into this panel:

The way he uses the curvature of the painting to add to and emphasize Paige’s inner strength is downright masterful. In this one panel — and even without any of the dialogue — we have a sense of the role she plays in her peer group and the intensity of her character. This is the kind of thing that a novelist would have to spend dozens of pages to build up, and Boss just lays it plain in the space of one little box.

Kids is crammed full of smart-asses and crotch jokes and all kinds of puns and witty dialogue. You get the feeling that if you were to tip it upside down and shake it, some of Boss and Rosenberg’s good ideas would fall out of the book like glitter because it's so overstuffed. But it’s affecting, too — particularly in one particular parental relationship that I don’t want to expand on for fear of spoiling the story. There’s an emptiness, an airiness in the relationship that can only be left by another human being, and that ache pulses off the page.

In the end, I can’t talk about Kids without repeatedly evoking the two words I used at the beginning of this review: exuberance and enthusiasm. Rosenberg and Boss demonstrate the kind of glossy-coat enthusiasm for the magic of graphic storytelling that only talented artists at the very beginning of a comics career can muster.

But I could show you landfills packed with enthusiastic books that are no damn good at all. It’s Boss and Rosenberg’s exuberance for the characters, and for storytelling, that make it all work so well. They’re not showing off for showing-off’s sake: they’re honing their excitement and their obvious love of the craft to best serve these characters, and to best tell this story. If it’s been a while since you read a book that was purely an act of love between artists and their medium, you owe it to yourself to pick this one up.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The hardest button to button

So as you probably know by now, writer Geoff Johns and artist Gary Frank are publishing a sequel to Watchmen titled Doomsday Clock. I don't really know what to say about the first issue of the book, except it is drenched in nostalgia. It's the kind of book that ten thousand teenage geeks dreamed they'd get to write after they read Watchmen for the first time. Doomsday Clock reads like a cover version of Watchmen, a mimicking of Alan Moore's tone without the intellect to back it up.

At least the art is pretty. Frank is one of the best contemporary superhero artists, though it must be said that his work is changing in an unpleasant way with each passing year. The faces of his characters are getting tighter and more pinched; the poses seem more coiled with every new page. The looseness and excitement of his early work seems to be replaced with a dour and puckered over-rendering, and it's kind of sad to watch. I want to start a GoFundMe to send him on a nice relaxing vacation or something.

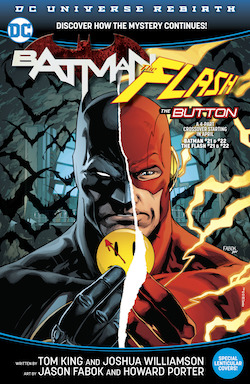

DC Comics published a prequel to Doomsday Clock in a Batman/Flash crossover called The Button, which is out in hardcover with a fancy cover that changes when you tilt the book. I enjoyed parts of The Button — writer Tom King's segments of the story, particularly a slow-motion battle between Batman and the ridiculous Flash villain Reverse-Flash, is laid out with King's customary attention to the rhythmic power of comics.

But The Button isn't just a callback to the Watchmen: it also homages the 1980s crossover Crisis on Infinite Earths, which suggests that perhaps there's even more of a callback to 1980s nostalgia in DC Comics today than Doomsday Clock lets on. It seems that every single book DC is publishing has to hearken back to its 45-year-old-male readership's childhoods in some form or another.

I can't really recommend either of these books, even though they're definitely appealing to a certain kind of reader. It doesn't really feel like there's anything new here, but unfortunately there are plenty of readers who might take that as a recommendation and not a criticism.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Now, for something completely different

The first issue of Now, a quarterly comics anthology from Fantagraphics, begins with a text page that falls just shy of manifesto territory. It's by Now editor Eric Reynolds, and it argues that "The anthology format can be an inherent force for good."

Reynolds makes a compelling argument. Anthologies are a great way for young cartoonists to get exposure and to experiment with styles without committing to a longform project. But nobody's really doing anthologies anymore. It's been years since Fantagraphics last dipped into the format with their gorgeous Mome series of bookshelf-ready paperbacks.

While still very substantial, Now seems more magazine-y than Mome, and that's a good thing: comics anthologies like this should feel of-the-moment and maybe not so permanent. And a good anthology needs a real reason to exist — a point to make, an argument to bear out, a fight to win.

So does Now live up to its name? Is it of the zeitgeist, or is it more of a nostalgia trip for a time when the comics industry was choking on anthologies?

The best comics in Now look like nothing else on the stands. The first page in the book, a strip called "Constitutional" by Sara Corbett, is absolutely gorgeous, a cross between a mannered kid's book from the 1950s and a deck of art deco playing cards. Nothing much happens in the six panels — an old woman and her cat go walking in a city park — but you can't stop staring at it, trying to figure out how a human hand could make something so eerily perfect.

Tobias Schalken's "21 Positions" feels like a magazine illustration from another time. It's just 21 borderless panels of a man and a woman dancing — or are they fighting, or are they fucking, or all three at once? — but as a comic it's something stripped down and raw and totemic. It's hard to pull your eyes from it.

A few comics veterans contribute pieces to Now. In "Scorpio," Dash Shaw tells a story of a couple whose baby arrives on election night, 2016. Gabrielle Bell's "Dear Naked Guy In the Apartment Across from Mine Spread-Eagled & Absent-mindedly Flicking his Penis While Watching TV" is pretty much what it says in the title. (It begins, "I know that you know that I know that you see me seeing you seeing me back.") Neither of these strips feel especially groundbreaking in relation to their respective artists' careers, but they're both haunting little vignettes.

There are 17 different pieces in Now, and they're thematically all over the place. Sammy Harkam's "I, Marlon" imagines the plight of mid-career Marlon Brando as he luxuriates on his private island. "Widening Horizon," by Malachi Ward and Matt Sheean, portrays a parallel history of space travel in a strip that might not be out of place in an especially adventurous issue of Popular Mechanics. Antoine Cossé's "Statue" is science fiction told in loopy, minimalist sketches. You never know what's going to come with the turn of a page, and every reader will find that some pieces of Now work better for them than others. (That's the whole point of an anthology.)

The most successful strips feel like they come from a slightly different universe, one where the lush aesthetics of magazine illustration fused together with comics. Given that magazines are nearly dead now — the Kochs will likely deliver the death blow to the long-suffering medium — it's heartening to see the mannered and deeply designed illustrations from magazine culture's heyday take refuge in the (relative) safe harbor of comics, where cartooning has held sway for over a century.

It's been years since I've seen someone in the comics world draw a line in the sand like this. Even Fantagraphics, which was practically a manifesto-producing factory back in the 1990s, hasn't made a declaration like Now in a while. Hopefully Reynolds will continue to explore this aesthetic in future issues of Now. This first issue proves he has the ambition, but it remains to be seen if the can turn that potential into a movement.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Justice is blind, Justice League is dumb

Ben Affleck is the perfect Batman for the era of Donald Trump. He’s huge and he often looks like he can barely move his arms. The nose on his mask is doing something weird that looks odder and odder the more you stare at it. He’s prone to saying gruff things that don’t really make sense. His plans involve talking a lot and not doing anything of value, and they almost always result in the situation getting worse. This is a Batman who is unintelligent, aimless, and way past his prime. Trumpy Batman is supposed to be the guiding light of the Justice League movie, which lands in theaters tonight. The team he puts together is a perfect reflection of Affleck’s surface-obsessed and unthoughtful Batman.

Let’s talk about Cool Aquaman. For decades now, Aquaman has been the butt of easy jokes: he’s got no personality and he talks to fish. Most writers have responded to Aquaman’s laughing-stock status by trying to make him extra-cool. (A recent Aquaman reboot saw the hero order fish and chips at a bar in order to demonstrate that he doesn’t give a shit about his finny friends.) Jason Momoa’s Aquaman, though, is Cool Aquaman taken to his extreme: he’s like a heavy-metal Yukon Cornelius, and he’s such a try-hard that all his coolness veers around into uncoolness again. He’s so fucking desperate to be seen as bad ass that he’s just an embarrassment.

Ezra Miller’s Flash is only slightly better. He’s supposed to be the funny wide-eyed can-you-believe-this-shit audience surrogate, but only about one out of every four of his jokes lands cleanly. The rest are awkward or just plain unfunny. And there’s not really anything to say about Ray Fisher’s Cyborg, a character who is noteworthy only for his ugly body of silvery CGI chunks.

So that leaves Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman. Rumor has it that after Justice League director Zach Snyder stepped off the film to deal with a family tragedy, fill-in director Joss Whedon added a bunch of Wonder Woman scenes to capitalize on her recent film’s fantastic reception. That was a smart move; Wonder Woman is the best character in the whole DC Comics film universe and Gadot is vastly improving as an actor from her wooden Fast and Furious days (though she does a few too many intense glares in this movie that all look exactly the same, and the male gaze lands on her multiple times in this movie, lingering on her body in sleazy ways that highlight the need to get more women directors behind the cameras of blockbusters immediately.)

These characters ostensibly get together because the world is awash in fear and loathing after the death of Superman in Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice. (One early scene seems to hint that anti-Islamic racism is on the rise because Superman is gone, which certainly is one way to try to seem relevant, I guess.) We never got to see this cinematic Superman as a figure of hope, but I guess we just have to take Batman and his pals at their word about this, because they keep talking about Superman as a figure of hope whenever the plot stops dead, which is pretty often.

Justice League is a fucking mess. The plot makes no sense. The special effects aren’t half-baked so much as shoved under a heat lamp for a minute or two. There are quite a few poorly shot close-ups of characters saying funny things that clearly happened in reshoots. Those shots are then wedged into the movie willy-nilly, with no regard for pacing or flow. It’s ugly and abrasive and dumb, dumb, dumb.

But maybe the worst misstep of Justice League is its villain: Steppenwolf. Canonically in the comics, Steppenwolf is big bad guy Darkseid’s uncle, and he’s not a major player by any means. In the film he’s a poorly animated all-CGI character who rants a lot about MacGuffins and conquest. He has no motivation, no physical presence, and he makes no sense. He’s chasing after some magic boxes that could mean the end of the world as we know it, and his tools include a large axe, a fleet of interchangeable flying monkeys who eat fear, and some tendrils of purple crystals that are supposedly a threat because they’re filmed in a slightly menacing way.

Justice League is so dumb, so obviously broken on a fundamental level, that it’s an insulting viewing experience. You’ll likely be seeing apologists on the internet saying that it’s “not a perfect film,” but that it “gets the characters right” and so it “sets the table” for future installments. To that faint praise, I say “bullshit.” Justice League isn’t a better movie than the disastrous Batman V Superman or the excrementitious Suicide Squad. It’s just tonally different from those movies — a desperate attempt to course-correct into brighter, more hopeful territory to quell fan complaints — and some overly forgiving souls may interpret that pandering as an increase in quality.

But trust me: This movie will not age well. You won’t watch it fondly on your own TV at home. It will look like a smear of gilded pixels on a tiny screen when you half-watch it in discomfort while sitting on an airplane. You won’t remember anything about it six months from now. One year from now, the silence that will surround this nearly half-billion dollar debacle will be a vacuum so deafening, so all-encompassing in its nothingness, that it may drive humans mad when they hear it. This is a void, and it consumes souls. Watching Justice League is like staring Donald Trump in the eyes and wondering at the nothing you find there.

Thursday Comics Hangover: An alternative to the alternative

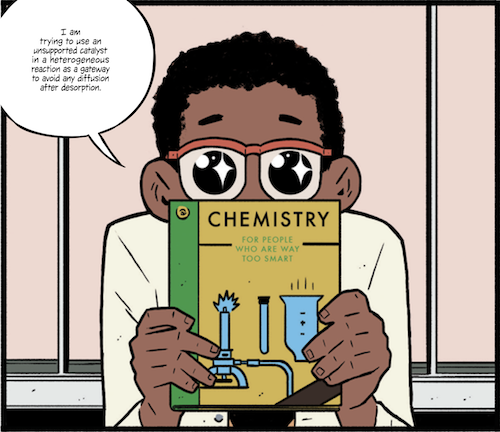

The newest issue of Marvel's The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl is billed as a "special 'zine' issue," which immediately grabbed my attention. I've always been a fan of alternative sensibilities applied to superhero comics — the Coober Skeber "Marvel Benefit Issue" is one of my all-time favorites, and DC's Bizarro Comics trade paperback is a lot of fun, too — and while I haven't read that many Squirrel Girl comics, the character is an appealing meta-take on the superhero genre, and I'd been wanting to read more.

The premise of this issue, laid out in a series of framing pages at the beginning and end of the comic, is that a library was destroyed in a superhero battle, and Squirrel Girl has assembled a benefit zine to raise funds to rebuild it. The comics are supposedly by Marvel heroes and villains, though it's really an anthology of one-and-two-page comics by a variety of cartoonists.

The concept is fine, but the execution is a little disappointing. There's nothing really zine-y about the comic. The creators are, for the most part, mainstream. Hell, Garfield creator Jim Davis is listed as a contributor, and you can't get any more mainstream than Garfield. (Davis's contribution is a series of strips replacing Garfield with Galactus and replacing Garfield's owner Jon with the Silver Surfer. That's it. That's the joke.)

A few of the strips in the issue are very good, particularly a self-help book narrated by a brain in a jar and a short little tone poem from the perspective of Thor's trickster brother Loki. And one strip drawn by Anders Nilson, involving Wolverine and a giant robot, gets the alternative spirit of the enterprise just right.

But I wonder what this issue of Squirrel Girl would have looked like if instead of summoning a fairly well-known ensemble of talent, the editors had gotten the contributors to the newest issue of Seattle free comics newspaper Thick as Thieves, instead?

Marie Hausauer's contribution to Thieves, a bar scene featuring a few trashy patrons hitting on each other, is creepy and true-to-life and beautifully rendered. On the next page, Travis Rommereim contributes a little gag strip about a man who abuses a talking severed head on a chain that taunts him with bad jokes and dares. ("Are you gonna shoot some arrows at me or what?")

Most of the strips in this issue of Thieves seem fairly well grounded in realism. There's a conversation between two young women, and a kid who plays with guns. Gil Rhodes tips things over into absurdity with a fantastic strip about a grandmother who repeatedly gives the worst advice ever, but even that strip doesn't beat you over the head with its surrealism. It's relatively quiet, and it's comfortable with the quiet.

I'm willing to bet that none of the contributors to this issue of Thick as Thieves are dying to work on a mainstream superhero comic. But that's part of the reason why they should have been asked to contribute. Marie Hausauer's Squirrel Girl really would have been an alternative comic to behold.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Anders Nilsen is speaking in Tongues

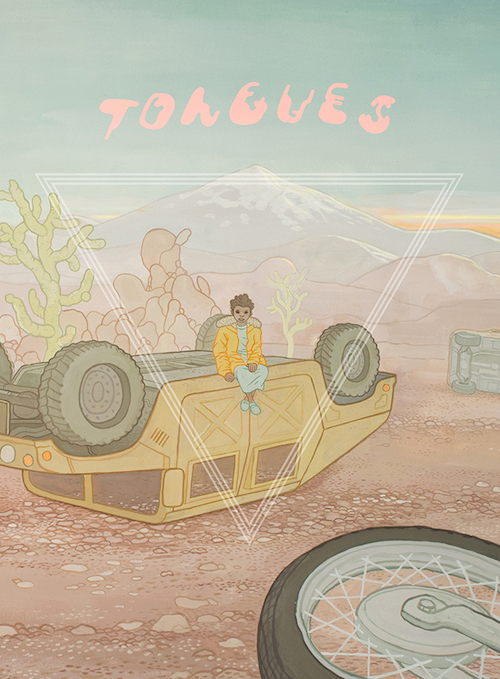

Portland cartoonist Anders Nilsen is a special guest at the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival at Seattle Center this weekend. You might know Nilsen from his Peanuts-meets-Tolstoy epic bird comic Big Questions, or his heart-rending memoir of grief and loss, Don't Go Where I Can't Follow. But at Short Run, he's debuting his latest ambitious project: the first issue of a projected series called Tongues.

Nilsen describes Tongues as "loosely based on a trilogy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, of which two plays are lost and only dimly reconstructed by historians." This first issue is loaded with references to the Prometheus myth, but projected through a fractured lens of American military action in the Middle East, and with a talking bird and a monkey thrown in for good measure.

Tongues is the most beautiful thing Nilsen has ever made. The pages are colored in rich pastels that absorb your attention. The overturned and ruined military vehicles in these stories aren't left out to rot in a garish yellow comic-book wasteland; these deserts are pink and shimmering, with whipped-cream mountains looming off on the horizon.

The illustration in Tongues surpasses just about everything that Nilsen has ever done before. His characters are finely wrought, but they feel secondary in the narrative to the oddly shaped geometric panels and the dreamy backgrounds. We're more invested in what a lippy crow has to say ("The humans are an object of fascination to me, too," he says to a Prometheus figure) than almost every human in the book.

The stories in Tongues are short, but they do resonate with the throbbing weirdness of myth. The obvious Prometheus allusions are one thing — it's hard to see a bird eating the entrails of a still-living man and not recall the Prometheus myth — but these pages of finely wrought military SUVs overturned in the desert recall the devastation of the Iliad. The ruins of the US Army look not unlike the battered Coliseum of Rome. In those broken cars, a monkey argues with a human over a dwindling supply of rations. In this context, it's a clash of the titans.

Nilsen's great skill is finding the depth and the adventure in any subject, no matter how small. With Tongues, he's re-envisioning his place in the cartooning firmament. His sense of scale has changed; whereas before Nilsen obsessed over tiny interactions, he's now ready to create some myths of his own.

Thursday Comics Hangover: It's alive! Alive!

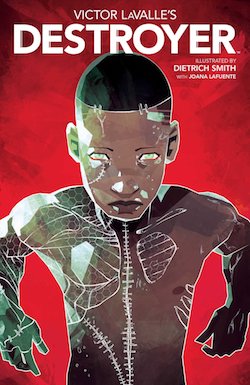

Victor LaValle is one of the most underappreciated novelists in America today. His debut novel The Ecstatic was less a shaky first outing and more a spectacular announcement of a singular talent. His last three novels — Big Machine, The Devil in Silver, and The Ballad of Black Tom — have addressed America's complicated relationship with race through the lens of horror fiction. (And before you ask, LaValle began exploring this relationship years before Get Out was anything more than a figment of Jordan Peele's imagination.) When it comes to genre fiction, he's one of our most fearless adventurers.

And now LaValle has conquered another medium. Yesterday saw the publication of the sixth and final issue of LaValle's very first comic series, Destroyer. Illustrated by Dietrich Smith, Destroyer is a modern-day recasting of the Frankenstein story. But this isn't a reboot; Destroyer is a sequel to Frankenstein. The original monster from the Wollstonecraft novel is still alive and menacing the characters of this story.

Destroyer's protagonist is a black teenage boy named Akai whose mother brings him back from the dead after he's slain by police. The book explores the mother-son dynamic and, since the mother is a descendent of Victor Frankenstein, the monster serves as a kind of lingering ancestral wrath. It's a story of grief and tradition and learning what you can and can't control about the things (and people) you create.

This sixth and final issue of Destroyer combines all those threads into one climactic scene. Every character gets an opportunity to make their case. ("Must be nice to be a father," Akai's mother notes bitterly, "Mothers are weighed on a broken scale.") The dynamics shift and realign and play out against a backdrop of America's forgotten history.

LaValle and Smith are creating high-level comics here. It's a book that is as personal as a love-letter, as brutally honest as a confession, and as of-the-moment as your Twitter feed. The final confrontation between Akai, his mother, and his father is just as internal and complex as any literary novel, but — because this is comics — it involves a giant, lumbering mech-battlesuit in mortal combat with a reanimated monster and a severed head.

The collected edition of Destroyer is set to arrive in bookstores in March of next year; if you've enjoyed allegorical takes on race in America like The Underground Railroad or Get Out, I urge you to reserve a copy at your favorite independent bookstore today.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Let the women speak

This week I want to talk about a book that isn't actually a comic book, but which wouldn't exist without comics. Catherynne M. Valenti's young adult short story collection The Refrigerator Monologues is an attempt to give voice to the often-neglected women who serve in supporting roles in superhero comics.

Refrigerator is structurally a riff on the Vagina Monologues with a superhero twist, and Valenti clearly knows her source material. The name comes from a superhero comic trope known as "fridging," in which a love interest's grisly death serves no greater purpose than really pissing off a hero, thereby giving him the motivation he needs to defeat the villain of the story. The book examines, satirizes, and deepens the cliches that women must endure in comics.

These are riffs on Spider-Man's first girlfriend Gwen Stacy (thrown off a bridge to her death by the Green Goblin) and Cyclops's girlfriend Phoenix (committed suicide after being tempted to the dark side by a cosmic being) and the Joker's girlfriend Harley Quinn (not dead, but often reduced to a punchline about codependency.) Valenti gets deep into the characters' heads, adding motivations and complex emotional responses to the crude stories mapped out in superhero comics of the past.

The framing story in Refrigerator, a club in the afterlife where wronged women can gather and tell their stories, doesn't quite go anywhere. And the book feels a little slight; it could use one or two more stories. But Valenti definitely ties together a thesis here, and she vindicates a whole rainbow of characters who have only gotten short shrift for the last fifty years. Hopefully next, she'll write a comic that puts these women front and center — without the men around to ruin everything.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The dream of the 90s is (barely) alive in Fante Bukowski

In the 1990s, a ton of male cartoonists made their careers by writing stories about schlubby men with huge egos. These self-important losers — from Buddy Bradley to Adrian Tomine's protagonists to Ivan Brunetti's self-portrayal — were important at the time: they poked necessary holes in the idea that the only stories worth telling were stories about straight white men of a certain age.

Cartoonist Noah Van Sciver's newest book, Fante Bukowski Two, seems to desperately want to be from the 1990s. It's designed to look like the Black Sparrow edition of Charles Bukowski's Factotum, and it has a completely realistic facsimile of a Borders price sticker on the back cover.

And the content of the book, too, feels ripped from the 1990s. It's a book about a bearded loser who believes himself to be the next Outlaw American Novelist, but who is in fact a talentless hack. Bukowski drinks too much, he lives on donations from his too-tolerant parents, he refuses to get a job. In this book, he lives in a flophouse and makes tons of zines and fails to sell copies all around town.

But the question that Van Sciver fails to answer is: who is this book for? Do we really need another book that skewers bloviating mediocre literary white men? Bukowski feels from the start like the alternative comics from the 1990s, and it never really stops wallowing in nostalgia for that era.

To be fair, Van Sciver is a talented cartoonist, and he has a great sense of comic timing. Parts of Fante Bukowski 2 are very funny. But I expect more than “funny” from a Fantagraphics title — the Seattle publisher has such a stellar publication history that I expect some sort of a point from all their books. Unfortunately, Bukowski feels like an exquisitely crafted fan fiction tribute to Fantagraphics titles from a bygone era.

And this question might seem petty, but it’s actually quite important: Do people like the person this book is supposedly satirizing even exist anymore? Do Bukowski acolytes still talk about the authentic human experience and produce zines to distribute at open mic nights? To me, this feels like a time-capsule, a skewering that arrives twenty years too late.

This is not to say that Van Sciver shouldn’t satirize white men, or that white men aren’t a relevant target anymore; quite the contrary. We live in a time in which mobs of bored white dudes are starting riots because their preferred flavor of corn syrup isn’t available at their local McDonald’s. If the self-entitled jackass star of Bukowski were alive today, his obsessions and behavior would likely be very different. With its obsessive backwards stare, Bukowski feels stale and hopelessly retro.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A dark Knight

I was 13 when I first read Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, and in retrospect I realize that it fucked me up for years. I wasn't mentally prepared to handle Miller's deeply conservative dystopian Batman comic, and so for a long time afterward I confused violence and nihilism for "serious art."

So many years later, Returns reads like a clunky piece of satire by a man who was teetering on the uncomfortable razor's edge between artistic curiosity and self-loathing regressivism. But the one thing it has going for it is its obvious merit as a work of art: when he wanted to, Miller could really put together a brilliant sequence panels. (Although I'd argue that the first Sin City collection, and not Returns, is his true masterpiece.)

Miller has now gone back to the Dark Knight well twice, with diminishing returns each time. The latest volume, Batman: The Dark Knight: Master Race, is out in a collected edition now, and I can't really think of a single redeeming value for this book. Supposedly co-written by Miller and Brian Azzarello, and drawn mostly by Andy Kubert, I'm almost unwilling to attribute Master Race to Miller at all — Miller himself says he had little to do with the actual inspiration for the thing — but his contributions to back-up stories in the volume seem to indicate that he at least had some say as an artist.

The most generous interpretation of Master Race is that Miller is trying to revive the fun high-concept sci-fi of the comics he read as a youth. The book, which depicts a war between older versions of Batman and Superman and an army of pissed-off Kryptonians, features DC mainstays like The Flash, Aquaman, and the Atom.

But the lack of technical proficiency defuses the reader's enjoyment on every page. This book is lazy and uninspired, like Dark Knight Returns fan-fiction written by someone who thought the only problem with Returns is that it didn't co-star the whole Justice League. Way too much of the book consists of sloppily rendered figures standing in front of empty backgrounds, which are then filled in with muddy reds and browns by colorist Brad Anderson.

Even worse are the backup stories, many of which are drawn by Miller himself. These stories are entirely non-essential, usualy explaining what some minor character from the main story is doing when he or she is off-panel. And don't get me started on the art. I think this is supposed to be the Eiffel Tower:

Sure, Returns was a story about a deeply fascistic rich man having a midlife crisis, but it was at least a well-rendered story about a deeply fascistic rich man having a midlife crisis. And Miller's overt acceptance of the underlying fascist tendencies in superhero comics was at least novel at the time.

Master Race doesn't even have the werewithal to take a stand on fascism. There's nothing pleasurable about this book. It's like a boy who melts his action figures with a purloined cigarette lighter and then bashes the disfigured toys all together until he randomly determines a "winner." The thing is a mess from the bottom up.