Archives of Thursday Comics Hangover

Thursday Comics Hangover: Too beautiful for this world

Aside from Ms. Marvel, my favorite Marvel title these days is Nick Fury, a spy comic written by James Robinson and drawn by the acronymical comics artist ACO. Fury is unlike just about everything else Marvel is putting out these days: every issue is its own stand-alone adventure, every page is visually adventurous, and the book isn't interested in crossovers or events.

Fury is a smart callback to the stylish Nick Fury: Agent of SHIELD book that Jim Steranko drew for Marvel during the late 1960s. It's not an homage, or a rigid tribute book: instead, it imagines what those SHIELD books would look like if they were drawn today. The result is a splashy, vivid, wildly attractive book that feels like a rich hit of pure comic joy. (Of course, Fury is not as subversive as Steranko's run, which still stands as some of the sexiest issues published by a mainstream American comics publisher. Fury is, unfortunately, rather sexless.)

The most recent issue of Fury, number 6, was published yesterday, and it continues the formula established in the previous five issues: Fury is on a mission in some exotic locale (this time he's in gothic Scotland) and he tangles with evil agents of Hydra. There's a plot twist that's so easy to predict it must have been planned that way, but that's not really what the book is about, in any case.

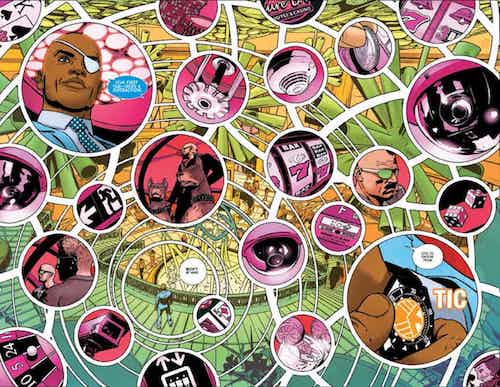

Robinson seems to have smartly designed this book to show off what ACO can do. A two-page spread reveals a hummming "Hydra enclave" buried underground, and ACO depicts a buzzing base full of drones and weird laser devices and all kinds of mysterious tanks full of evil stuff being carted around. Later, ACO delights in taking the whole base apart, piece by piece, as Fury unravels their plans. I haven't stared this intently at pages of art from one of the big two publishers in a very long time. Here's a spread from an earlier issue of the comic, which shows Fury examining every possible threat on a wide-open casino floor:

Unfortunately, the last page of Fury delivers some bad, if predictable, news: number 6 is the final issue. It figures: Fury was too beautiful to live in this world. Hopefully, ACO will land a gig that offers the superstar status he deserves. Until then, lovers of over-the-top spy fiction will have to keep their spirits up with the trade paperback collecting every issue of Nick Fury, which is due out this December.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A Bonding experience

I try not to give Birth Movies Death any web traffic these days due to the noxious way the site's owner protected former BMD editor Devin Faraci in the wake of sexual assault accusations. But it's impossible for me to separate my viewing of Kingsman: The Golden Circle from a 2015 essay on the original Kingsman film by Film Crit Hulk.

I found the first Kingsman movie to be boorish and awkward in its handling of James Bond satire, though I did appreciate the way the film addressed the inherent classism of the Bond mythos. Hulk's essay didn't necessarily convince me to reappraise Kingsman as a brilliant work of art, but he did argue that the filmmaker, Matthew Vaughn, knew exactly what he was doing with the film: that Vaughn was producing, essentially, the world's only honest blockbuster movie — one that embraced the political discomfort of Bond movies.

Kingsman, of course, is adapted from a comic book series written by Mark Millar, an amoral dolt who has lowest-common-denominatored his way to great success. (I wrote about Millar in this space not so long ago.) Vaughn has taken the basics of Millar's premise — what if a poor kid became the next James Bond? — and made all the class issues entirely overt. Young Eggsy (a charismatic Taron Edgerton) is a chav who gets recruited by a Bond-like agent (Colin Firth, clearly having a lot of fun) to join a secret organization of spies who defend England from outsize global villains.

Despite a few missteps, (Samuel L. Jackson offers maybe his worst performance since Frank Miller's Spirit adaptation) even the most skeptical viewers had to admit that Kingsman was entertaining as hell, a skosh of R-rated blockbuster ultraviolence to while away time in the multiplex.

The Golden Circle will likely not invite a high level of investigation from writers like Film Crit Hulk. It is, to put it bluntly, a bad movie. It's boring and it's weighed down with exposition and the attempts at humor don't land successfully. If the first film was a sly investigation of class, the second film can't even convincingly sell itself as an investigation of how awful sequels usually are.

Of course, parts of The Golden Circle work really well: Vaughn's action sequences are buttery-smooth and boundlessly fun to watch. Julianne Moore, as the breathlessly chipper drug-dealing villain, is fantastic. Her character's plans to change the world are more interesting than your standard movie bad-guy dreck. Edgerton and Firth maintain their excellent rapport from the first film.

But most of The Golden Circle is self-serious and overblown. Channing Tatum shows up for about ten minutes of screentime, total. Some of the action sequences feel weirdly weightless. Other scenes fail to keep the plot moving forward. I have a hard time picturing any serious claim that The Golden Circle is another showcase of Vaughn's sly satirical skills. The class elements of the first film have basically disappeared, and the Bond nods feel less playful and more obligatory.

The Golden Circle is one of those rare sequels that actively diminishes the film that came before it. It's a film that's just as dumb as the comic that inspired it.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Blue collar special

On Labor Day, I argued that we need more blue-collar novelists. The thing that I didn't note in that essay is that there are plenty of contemporary blue-collar cartoonists — not because the comics industry is so forward-thinking but because the comics industry does such a poor job of compensating artists for their work. Unless they're a superstar name or someone who works on a number of different gigs simultaneously, the odds are good that your favorite cartoonist is either A) indepdendently wealthy or B) working multiple angles to make ends meet.

Madge feels pretty grown up when she scores a job at the Imperial. She's living with roommates, she gets a boyfriend, and she falls for the eccentrics who frequent the Imperial — on both sides of the counter. But soon enough, people start ODing on heroin, or doing too much coke and getting violent, or having brushes with the law. It's a coming-of-age story set in the school of hard knocks.

Tying together all of the anecdotes that make up Wrong is the work: waiting tables is the baseline of the book. Madge walks around with a carafe of coffee in one hand, chatting with customers, learning what she can about the world from the booths of the Imperial. Sometimes the kitchen is slammed and Madge has to try to charm her tickets to the top of the to-do pile. Other times it's slow and she shoots the shit with regulars. It's a book that's intrinsically tied to the dignity — and indignity — of work.

At nearly 450 pages, Wrong is a mammoth-sized comic. You'll have to take your time with it, and that's how it should be. It's a memoir that takes you through the days and nights of its main character, and it slowly transforms Madge in such a way that the reader barely notices until the transformation is complete.

Pond's art is perfect for this kind of serialized novel of a story: her art is cartoony but finely detailed. Madge's face is just a couple of lines, but Pond draws every stave in the row of chairs in the background. This makes the run-down glory of the Imperial, and of pre-tech-boom Oakland, an additional character in the book. You're not likely to read another comic this year that immerses you so deeply in the lives of a cast of characters, and these are lives — endearing, aggravating, tragic — that you don't see enough in modern fiction. Cartoonists like Pond are happily taking up the space that novelists have abdicated.

Thursday Comics Hangover: These bottoms are the tops

Next week, editor J.T. Yost will debut his new comics anthology, Bottoms Up! True Tales of Hitting Rock Bottom, at the SPX alternative comics festival. In his introduction, Yost identifies the book as a labor of love, an “attempt to humanize addiction through real stories told by actual addicts.” The book features a wide array of contemporary alternative comics talent, including Seattle cartoonists Tatiana Gill and Max Clotfelter.

Addiction stories can be formulaic, in part because audiences intimately understand every rise and fall of the narrative. If things are looking good for the characters in the story, astute readers know that the next decline is just around the corner. Yost’s decision to focus only on the worst possible moments is canny: all the buildup and false promises of traditional recovery narratives are trimmed away, leaving only the central pivot of the story.

The definition of “rock bottom” varies wildly from artist to artist. Some of the moments are funny (the protagonist of Clotfelter's story realizing that the woman he slept with has a full-back tattoo of the Confederate flag and the words “Dixie Bitch”) and others are horrifying (Matt Rota’s long story “That Summer, Way Back” involve a heartbreaking case of animal neglect.) Others, like Victor Kerlow’s “The Big Joke,” depict rock bottom as an abstract emotional state — the complete falling-apart of ego as depicted by a body slicing itself into meaty slivers in an almost-overdose.

Not all of these stories are autobiographical; many are anonymous tales told to the cartoonists, who then interpret the stories in their own styles. Daniel McCloskey depicts one man’s account of a near-suicide through the lens of Taylor Swift’s single “Shake It Off,” and the story blissfully skirts the line between bad taste and good comics. Adam Pasion’s adaptation of another anonymous storyteller’s descent into digital voyeurism somehow manages to portray the creepiness of the addiction while not feeding the reader’s prurient interests. Two of the stories involve imaginary pets. At least one involves regrettable hot tub sex.

Even if you’ve never woken up from a blackout haunted by a familiar gnawing fear in your gut, you’ll likely find a reflection of yourself somewhere in Bottoms Up! There’s no single thread through all of these stories except that most basic human failing: our frustrating ability to let ourselves down, despite our own best intentions. There’s something incredibly comforting about reading a whole book of failures — funny failures, sad failures, tragic failures — told by people who lived to tell the tale.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Dumbforgiven

My favorite writing podcast isn’t about poetry or novels or non-fiction. It’s about screenwriting. John August and Craig Mazin’s Scriptnotes is a long-running podcast that takes listener questions, offers industry interviews, and occasionally pulls screenplays apart to see how they work. While Mazin and August are sometimes a little too conventional in their advice — the film industry does love a formula — they’re great hosts who cheerfully provide useful information, and they’re terrific in the way they treat writing as a craft and not divine inspiration. Any writer could learn a lot from the way they discuss their jobs.

In their most recent episode — embedded above — August and Mazin discuss the script for the Clint Eastwood masterpiece Unforgiven. It’s one of their best episodes, because their obvious enthusiasm for the script shines through in every moment. They rightfully praise Unforgiven for its economy: every line in the script either advances the story or establishes theme and character, or (most likely) both. They discuss why the screenwriter, David Webb Peoples, made decisions that contradict every piece of advice you’ll read in screenwriting guides, and they debate decisions that Eastwood made as he translated the script to screen. I encourage any writer to listen to this podcast.

So. What does all this have to do with comics?

I’ve been thinking a lot about comics writer Mark Millar lately. Millar made news earlier this month when it was announced that he sold his creator-owned comics line, Millarworld, to Netflix in a development deal that has been rumored to be somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 million. Millar has been praised as “the Quentin Tarantino of comics,” likely because his books are generally full of “adult themes” like violence and swearing in a way that superficially resembles the aesthetic of Tarantino films.

If you enjoyed the X-Men spinoff film Logan that was released in spring of this year, you probably know that it’s based on a Millar comic called Old Man Logan. Logan is far superior to Old Man Logan, in part because it’s handled with a maturity that continually escapes the comic. Millar’s Old Man Logan is a trashy joyride through a dystopian Marvel Comics future — one in which the Hulk fucks his own cousin, Spider-Man’s daughter is repeatedly ogled as jailbait, and the Red Skull dresses up in Captain America cosplay for cheap shocks.

At the time of its release, and repeatedly in years since, Old Man Logan has been sold to audiences as Unforgiven starring Wolverine. Superficially, that connection makes sense. Old Man Logan centers around an old man who was once a fearsome warrior but who hasn’t taken up arms in years. He’s reluctantly pushed back into his old life, and he’s eventually subsumed by the violence that swallowed his youth. In both stories, the hero is a threat, one that is teased from the very beginning of the story and only rolled out at the very end. It’s the same basic plot structure.

But listening to Mazin and August enthuse over what makes Unforgiven special really hammered home everything that’s terrible about Old Man Logan in specific, and Millar’s writing in general. Unforgiven is thematically about the stories we tell each other, and the distance between stories and reality. Old Man Logan is nothing more than a string of “cool” moments. It’s not about what it means to be a killer — Old Man Logan is a celebration of violence, written by someone who seems to think that Unforgiven exists so that Clint Eastwood can, in the end of the movie, shoot a bunch of people and look badass while he’s doing it.

And ultimately, that’s what all of Millar’s books are: bad misreadings of popular culture. His books build on premises that every 15-year-old comics nerd has idly wondered: What if Batman was actually the bad guy? What if Flash Gordon starred in Unforgiven? What if the bad guys killed all the superheroes? And then it does nothing more than revels in the “coolness” of the premise, providing a string of money shots that forcibly injects chills into the cerebral cortex of fanboys.

Of course, I suspect this off-brand hucksterism is not a bug for Netflix, but a feature. Comic book movies and shows based on Millar’s comics will appeal to the penny-pincher in all of us. They look enough like the real properties to be enticing to our basest instincts, and they’re stuffed full of enough violence and nasty thrills to keep us watching. And sometimes — as in Logan — talented filmmakers might be able to transform Millar's doggerel into verse.

As an investment, I'm sure Netflix feels pretty good about the content they bought. Unfortunately, Millar — who always reaches the most facile decisions — will only be emboldened by their purchase. He's just getting started.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Same shit, different costume

Most modern superhero comics feel like action figure catalogs. Every story involves a new costume, or an alternate-reality version of a character, or a new character taking over the title temporarily. It just feels like the creators are stewards of an IP, adding value to the original concept by spinning a variant into existence that will one day be molded into plastic and sold.

The first issue of artist Greg Capullo and writer Scott Snyder's DC crossover comic Dark Nights: Metal is basically everything modern audiences want in superhero comics: wall-to-wall action, decorated with a bunch of Easter eggs that call back to decades of convoluted continuity. It opens with the Justice League in outer space, being forced into gladiatoral combat, and it expands into a secret society revealing the imminent invasion of a grave threat that might destroy the universe or whatever.

Snyder and Capullo create at least two sets of likely profitable action figures in the first ten pages of this book: Gladiator Justice League and Voltron Justice League. Later, we see silhouettes indicating yet another variant: Evil Alternate Universe Batman Justice League. Plus, Batman rides a dinosaur and he almost says the word "ass," both of which are sure to wind up in some listicle on some zombie comics news site as one of the Top 15 Most Awesome Moments In Comics This Year. (You can practically read the breathless copy now: "Four words: Batman. Riding. A. Dinosaur. 'Nuff said.")

There's an obvious high level of competency in the actual craft of the comic. Snyder is very good at getting information across in a very small space, and Capullo is better than most superhero comics artists at designing a page. They seem to work well together, and the book is technically very proficient.

But the last page involves a character who simply shouldn't be there. I won't spoil the big surprise, but let's just say it's akin to the revelation that DC Comics is incorporating Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's Watchmen comics into mainstream DC continuity. It feels like another pointless violation of another barrier, and it cheapens a much-loved comics property by turning it into a plot point. But hey — at least it'll make a really cool action figure line one day.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Scary stories to tell in the dark

You've gotta love a comics anthology built on a theme. There's something so conversational and warm and inquisitive about collections of short comics, particularly when they're all examining a particular idea from a wide variety of perspectives.

The 19th issue of Not My Small Diary — part of the My Small mini-empire created by Delaine Derry Green (the zine creator known best for her long-running series My Small Diary) — is an anthology of 43 autobiographical comics about unexplained events. As you might expect, the stories range from the outright supernatural (lots of ghost sightings) to the merely coincidental (immediately after having a dream about a mugger stealing $20 from them, a cartoonist is handed $20 by some random guy on the street.)

This particular issue of Not My Small Diary is loaded full of Seattle cartoonists including Noel Franklin, David Lasky, Kelly Froh, Donna Barr, Max Clotfelter, Colleen Frakes, Mark Campos, Ben Horak, and Roberta Gregory. It's with more than a little pride that I note that Seattle contributes some of the strongest pieces in the book, including Franklin's creepy crow story, Campos's short tale of the six words you'd least like to hear from thin air in the dead of night, and Frakes's account of the time she accidentally entered into a family's haunted living situation.

Ranging in tone from skepticism to avid believer, these comics combine to form a wide-ranging study of experiences and feelings about paranormal activities. It's kind of like a long sleepless night swapping stories around the campfire. Some of the stories are total bullshit; others feel a little too true for comfort. No matter where you stand on UFOs and ghost stories, you'll find something to appreciate here.

Thursday Comics Hangover: For mature readers

Aside from Charles Schulz's Peanuts, American comics aren't great at melancholy. I've read plenty of depressing comics, and many upbeat comics, but the gentle downward slope of melancholy seems too subtle for most American cartoonists to capture.

The 20th issue of Chip Zdarsky and Matt Fraction's series Sex Criminals is about a breakup. Neither party seems to want to break up, but they both understand that they have to do it. They have sex, even though they know they shouldn't. They have trouble articulating the things they know they need to say. They are uncomfortable in the moment, and they both know it.

Meanwhile, in another scene, a middle-aged man and woman have sex. She's a retired sex worker. He's an academic. His reaction to her past is getting in the way. She's seen this before. She's tired of it, but she explains it to him anyway.

Sex Criminals has always been a special comic. It's based on a one-note gimmick of a plot — a man and a woman find that they can stop time with their orgasms, so they go on a fuck-fueled bank-robbery spree — but it has somehow expanded to incorporate a rainbow of sexual interests, personalities, and questions about what it means to be human. It's explored adult romantic relationships with a subtlety that most modern literary novels can't touch. The depiction of depression in an early issue felt truer and more honest than most memoir. For those reasons and more, the series continues to be a miracle of the American comics industry.

But issue number 20 is something else again. It has the feel of a deep-autumn Charlie Brown strip (albeit one with explicit illustrations of adult genitalia) and it perfectly captures the responsibility and difficulty of adult life. New readers will be entirely lost — hell, I can't keep track of who all these characters are, and I've been following the book since the beginning — but those who have read the whole thing will find a remarkable maturation in the book's already-mature themes. If Sex Criminals keeps up like this — and if it, uh, climaxes in a, uh, satisfying way — it could be one of the all-time great serialized comics.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Coates check

I have to admit something: I loved the first issue of Ta-Nehisi Coates's Black Panther, but the series has largely lost my interest in the intervening year-and-a-half. That first issue was a perfect balance between pop-culture philosphy and superhero action, and Coates seemed to be attempting a more stylish version of a text-heavy style of comics writing that we haven't seen in mainstream comics since the 1980s.

But gradually, over the next few issues, Coates's writing went from wordy to overindulgent to bloated. Long stretches would happen where people would talk in self-important prose and all the important story beats seemed to be happening off-panel. The recap pages would contain more palace drama than the actual comics pages.

And to cap it all off, Brian Stelfreeze, the artist who started Black Panther with Coates, seemed to entirely disappear. Stelfreeze has always had difficulty hitting a monthly deadline, but this book used so much of his visual language that when he stopped drawing the title, the characters seemed to lose their motivation with him. I ordinarily adore Chris Sprouse, the artist who has taken Stelfreeze's place, but Sprouse's superheroic figures, who always seem ready to leap off the page their impossible musculatures and lantern jaws, feel badly mismatched with Coates's action-free scripts.

All that said, the latest issue of Black Panther, #16, is the most exciting issue in a long time. In just a few pages, Coates manages to reinvigorate a background character from the Marvel Universe in a way that feels entirely authentic and thought-provoking, yet still true to the character. The few scenes with this character combine social commentary, some fun writing, and a genuine passion for the Marvel Comics framework.

But it's not enough to salvage the whole issue. Back-up characters appear and disappear with no explanation. The story wants to raise stakes without actually investing in building the drama, and Coates can't seem to find a working rhythm for the book.

Perhaps Black Panther reads differently in trade paperback; it's possible that it flows better when given the same attention one would apply to a novel. But as a monthly comic, it's consistently the least interesting book in the stack I bring home from the comic shop. The great promise of that first issue feels squandered.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Say something nice

A considerable portion of Seattle’s comic book talent is in San Diego this week at the corporate pop cultural orgy known as San Diego Comic Con. It makes sense to take stock of comic culture at this time of year, because it’s the closest thing to a High Holy Days in the nerd calendar year. Look anywhere on the internet right now and you’ll probably find an equal share of breathless odes to SDCC and vicious takedowns of everything having to do with the crass commercialism of nerd culture.

The thing is, I do enough whining about corporate comics in this space. And so for Comic Con, I thought I’d point out seven comics series that I’m genuinely excited to read every month. Prepare for niceness:

Ms. Marvel is the best comic that Marvel publishes. It’s consistently great — a deeply personal celebration of the superhero myth.

Paper Girls from Brian K. Vaughan and Cliff Chiang evokes a wide array of sci-fi source material — Stranger Things, Lost, Steven Spielberg and Stephen King — while still feeling completely original. It’s a time travel comic that has seemingly been planned down to the last detail, an adventure comic that places character at the forefront of the story, and a touching story about growing old while combating nostalgia.

Giant Days is a perfect sitcom of a book, about a group of young women trying to navigate the adult world. It’s funny, but not in a way that sacrifices the dignity of its characters. It’s sweet, but not cloyingly so. Giant Days is about as likable as a comic can be.

The Black Monday Murders imagines a world where money is power. Okay, but like magical power. It’s a murder mystery set in a world where America's wealthiest families have amassed dark magic along with their wealth, creating a metaphor for income inequality that is perhaps more vivid than any I’ve ever read.

The new comic by underrated novelist Victor LaValle, Destroyer, is a fresh take on the Frankenstein story that addresses race and police violence in a meaningful way. It’s the second-newest comic on the list, but it looks to be a work that will add to LaValle’s shelf full of novels that use genre to investigate the black experience in America.

I just wrote about the first issue of Calexit last week, but I’ve thought a lot about this book in the past seven days. It’s not often that a single issue of a comic lives in my head like this.

Kill or Be Killed is the closest thing to Taxi Driver I’ve read in comics form. It takes vigilante justice to its logical conclusion in a story narrated by a damaged man who murders people he believes to be criminals.

And here’s a bonus comic: yesterday I picked up the first issue of Generation Gone, an Image series written by Ales Kot and illustrated by André Lima Araújo. It’s very promising. The story is about three young hackers who are preparing to steal an obscene amount of money from an obscene too-big-to-fail bank. The class struggle is real: “These children are millennials,” someone exclaims in the middle of the issue. “Men like you have taken their future away from them. They are getting ready to steal it back.”

Araújo draws a diverse cast with expressive faces and he lays out the action through a wide variety of perspectives. It’s a kind of realism that draws you in and lulls you into complacency. Just when you think this is a book about normal people in normal rooms doing fairly straightforward computer-y things, the twist kicks in and you understand that Araújo has a wider range than you first expected: he’s a rare horror artist whose work is genuinely scary.

This first issue of Generation Gone is all set-up. It’ll make for a compelling first chapter in the inevitable collected volume, but readers of the first issue might be annoyed that just when the book gets started, it ends. Still, if you give it a chance you'll find a well-written and superbly illustrated high-concept first issue of a series — one that could well wind up on your list of favorite monthly comics.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Fighting Trump in comics

Volume two of Françoise Mouly and Nadja Spiegelman’s comics anthology Resist! Grab Back! was sitting in the free stacks at Phoenix Comics last night. Even though it says “FREE” in big block letters on the front of the book, it still felt a little like shoplifting to walk off with it: it’s a 48-page full color anthology of anti-Trump comics by cartoonists from around the world. If you were to roll it up, it would likely be thicker than your wrist. It feels substantial and raw and pulpy, like an old issue of Maximumrocknroll, back in the days when people paid money for tiny classified ads.

Resist is a woman-centric collection of anti-Trump comics, and Seattle is well-represented here with artists including Linda Medley. You’ve very likely seen some of these strips online, because political comics circulate faster than venereal diseases on social media nowadays. But when taken in aggregate like this, even the repeats gain a certain kind of power. The quality of the comics vary, of course, but they amount to a cartoon manifesto of sorts, an enthusiastic nose-thumbing at the Trump administration.

Many of the strips focus on menstrual blood as a sign of resistance. (One of my favorites is an anonymous strip encouraging readers to mail bloody tampons and pads to Mike Pence and Paul Ryan.) Others are pieces of journalism. A few of them are gag strips. Not all of them work — Art Spiegelman’s strip depicting Donald Trump as a literal pile of shit has a whiff of desperation to it — but even when a strip doesn’t appeal to the reader, there’s likely a better one just a page turn away. An omnibus of this size and this intensity simply cannot be ignored.

Still, Resist! does feel a bit like an artifact. It’s full of accounts of the Women’s March, which seems like eons ago in the hyper-speed perpetual news cycle we’ve been trapped in all year. A few of the strips are from the days when Steve Bannon seemed like the biggest problem we’d face. And that early sensation of #Resistance depicted in the book — that early idea that we’ll keep up with a relentless schedule of enthusiastic protests every weekend — has faded into a grimmer sense that we’re trudging forward, learning from our mistakes, and preparing for a long haul.

If you’re looking for a piece of comics art that feels as fresh and as lively as a spray of breaking news from Twitter, you’ll have to turn from the free shelf at Phoenix Comics over to the new arrivals wall. Yesterday, the first issue of Calexit was published, and the book couldn’t feel more immediate if it was drawn right in front of you. If you’re the kind of person who avoids the news, author Matteo Pizzolo and artist Amanday Nahuelpan’s story of what happens when liberal parts of California and other West Coast cities secede from the union after a fascist takes control of the United States might make you nauseous.

In a note in the back, Pizzolo explains that Calexit predated the election of Donald Trump, but it certainly leans into the imagery now that we’re here. The second panel of the book depicts a small-handed president announcing that “it’s been two big league years since this nation re-elected me, and I realize California wasn’t smart enough to side with the winner, but I’m still gonna take care of all you citizens.” That’s the only Trumpian appearance in the book, though one character does bear a striking resemblance to Steve Bannon.

So, what’s life like in California and the Pacific Coast Sister City Alliance? It’s pretty tense. The book opens with a delightful conversation between an armed Homeland Security agent and a Californian drug smuggler named Jamil just outside Mann’s Chinese Theater. “As your pharmacist for many weeks now, I’m a bit concerned about this move for you from uppers to anti-depressants,” Jamil tells the soldier. “You feeling okay?” They’re chummy but slightly antagonistic, and their relationship is a good metaphor for the city of Los Angeles as it prepares for a visit from the President.

The atmosphere in Calexit isn’t one of out-and-out civil war. It’s more like the Balkan states: heightened tensions everywhere, pockets of resistance bubbling up here and there, and the promise of a never-ending battle skulking around every corner. There’s even a schlubby Captain America wandering around in the background to remind us that it’s all taking place in Hollywood.

The pacing in the first issue of Calexit is excellent, the characters are well-defined, Nahuelpan’s art is detailed and expressive, and the world established in the story is entirely too believable. The incident that triggered the Calexit of the title is a hardline immigration ban, and the creators address issues of race with compassion and intelligence. The book takes its intellectual responsibility very seriously: Pizzolo interviews various political thinkers and actors and publishes transcripts of the interviews both in the back of the book and on the book’s website.

It’s always hard to predict where a series will go on the basis of its first issue, but I am fully on-board after reading the first installment of Calexit. It’s a highwire act that could go wrong at any moment, but Nauelpan and Pizzolo seem like the right team for the job. They’re not just responding to Donald Trump’s actions like the cartoonists in Resist!. Instead, they’re creating their own world and examining a framework — however fictional — for revolution.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Choose your Spider-Man

When it comes to Spider-Man, you're either a fan of the Ditko take on the character, or you prefer John Romita. Ditko, of course, created Spider-Man — with some assistance from Stan Lee — but Romita took over the series from Ditko and codified it into the Spider-Man we know today.

It breaks down like this: Ditko's art is weird and a little off-putting and gorgeous. Romita's lines are much cleaner and less complex and more outright heroic. Ditko's version of Peter Parker sulks off to the side of his schoolyard while everyone else socializes. Romita's version is much more mainstream and friendly. Ditko's Spider-Man was paranoid and weird and always in danger of getting angry and hurting someone. Romita's Spider-Man is on all the licensed Underoos and bedsheets, as unthreatening in his own way as Mickey Mouse.

You can probably tell from my description where I stand. I much prefer Ditko's take on Spider-Man, which feels to me like a more realistic portrayal of adolescence. The teen years are lumpy and awkward and infuriating, and Spider-Man should reflect that.

By far, the two best Spider-Man movies to date are Sam Raimi's Spider-Man 2 starring Tobey Maguire and the new Spider-Man: Homecoming, which opens tonight in theaters everywhere and stars Tom Holland. Of those two, I prefer Raimi's edition, which to me more accurately reflects Ditko's take on the character. Maguire was a mildly creepy Spider-Man; he always had a bit of a leer on his face, and he felt more dangerous than cuddly.

But if you like the Romita Spider-Man, odds are good that Homecoming might be your favorite Spider-Man flick yet. And you'd have good reason to fall for it. This is a funny, entertaining, thrilling superhero movie with great performances anchored by a stellar Tom Holland, and some of the best direction we've seen in a Marvel movie.

Jon Watts, who previously only had one movie — the pulpy thriller Cop Car — to his name, does incredible work here. Watts isn't afraid of pulling the camera waaaaaaaaaaayyyyy back and giving us a long shot, say, of Spider-Man running down a street, or of him goofing around with his webs, or of Peter Parker walking down the hallway of his high school for gifted and talented students. Watts allows things to look a little mundane, which is smart: it humanizes Spider-Man and puts him on our level. We can't help but root for him.

I don't want to give away too much of what little there is of the plot, but suffice it to say we don't dwell on origin stories here. Instead, we just follow Peter Parker around on a few important days in his life, and we watch as he interacts with his hero Tony Stark and a birdlike villain played by former Birdman Michael Keaton. The set pieces are suitably big but happily lower-stakes than most superhero films. (Only the last action sequence falls prey to the too-many-blurry-closeups school of superhero storytelling, and even then the film manages to stop itself before it goes too far down that road.)

You'll see some folks try to claim that Homecoming is a tribute to John Hughes movies, but that's stretching it. While the film does focus on the relationships between Peter Parker's peer group (say that five times fast), it's by no means a romance, or a quiet, character-driven story. Instead, it deepens and investigates the Marvel Universe's impact on ground-level citizens in a meaningful way. Keaton's bad guy has an honor to him, and though he's not as fully developed as Alfred Molina's Doctor Octopus was in Spider-Man 2, he's certainly one of the better Marvel villains.

But while the film has at least one huge homage to a Ditko moment, it's Romita Spider-Man through-and-through. Parker is portrayed as a nerd, but aside from one comic-relief bully, you get the sense that he's still respected by his classmates. His relationship with his Aunt May (Marisa Tomei, wildly charming) is healthy. He doesn't feel like too much of a freak when he teams up with other superheroes. (Remember, Ditko's Spider-Man tried to join the Fantastic Four in his first issue, but when he found out that they didn't pay well, he threw a hissy fit and acted in an otherwise very unheroic manner.)

I wasn't super-impressed with the last few superhero pilot outings from Marvel. I thought both Ant-Man and Doctor Strange were perfectly respectable, if relatively bland, outings. Homecoming is much better than both those films, though it does certainly feel like yet another installment in a never-ending story.

That's okay, though. Whichever Spider-Man you prefer, Ditko's or Romita's, you have to admit that both are well-crafted comics. It's kind of the same thing here: after a dry spell of three bad movies, it's heartening to see a talented group of artists get their hands on the character again. Even if this Spider-Man is a little too friendly for your liking, you have to at least love him a little bit.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Meet the B-Side Batman

I read the first issue of Mother Panic, a comic from My Chemical Romance frontman Gerard Way's Young Animal imprint of DC Comics, when it was first released over half a year ago. I didn't think too much of it — the comic suffered from first-issue-itis, wherein a lot of things happened but we weren't told why we should care.

Last week, DC published the first collected volume of Mother Panic. Titled A Work in Progress, the book collects the first six issues of the series. When read all together like this, the story is good enough to make me feel embarrassed for giving up on the series too soon.

Mother Panic is a weirder, more experimental B-side to the character of Batman. It begins with a young celebutante named Violet Paige who returns home to Gotham City after some time away. When Paige isn't posing for the paparazzi, she's putting on a costume and acting out her vigilante fantasies on the streets of Gotham.

But while Batman and his attendant bat-heroes all dress in shadowy blacks, Mother Panic wears head-to-toe white. Her head is concealed behind a giant pointy white helmet. She wears enormous white gauntlets. While Batman is haunted by his dead parents, Mother Panic is haunted by her living mother — her brain addled by early onset Alzheimer's, Paige's mother lives in a fairy-tale land constructed in Paige's mazelike home, never quite making sense but still providing guidance through her cryptic observations. ("Here. Sometimes the audience should get flowers," she says early on in the series, as though she's talking right to the reader.)

If superheroes represent wish fulfilment, then Batman appeals to people who want total control over every situation. While Batman is all about control, Mother Panic is kind of a mess. She screws up a lot and shouts "FUCK FUCK FUCK!" when things don't work out. She shouts "FUCK YOU, TOO" at whichever agent of Batman happens to be spying on her at any given moment. She's all id and art, the flipped coin to Batman's boring overpreparation. I'd much rather be a Mother Panic than a Batman — deep down, I think she's having more fun.

The first two issues of the book, illustrated by Tommy Lee Edwards, are my favorite. Edwards' style is perfect for the character: he draws with a severe line that belies a certain cartoonishness rubbing just under the surface. Later issues are drawn by Shawn Crystal, who has a looser, more caricatured style. Both artists keep things nice and claustrophobic, rarely ever giving us a pulled-back shot. These are close quarters, and we are up in every character's face, with colorists Jean-Francois Beaulieu's deep reds and angry purples giving everything a certain cast of danger.

While most Batman-adjacent characters replicate the character's formula without much variation, Mother Panic feels like a weird interpretation of the idea — Batman run through Google Translate and back a few times, or set to a rumba beat, or played at 1.5 speed. It's one of the most interesting variations on the character that I've seen since Grant Morrison stopped writing Batman. I want more weird modern melodrama like this in my superheroes.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A fan's notes

The following is an email we received from a reader named Joaquin de la Puente:

A question for Paul Constant: I just read your review of Josh Bayer's Atlas #1 and found it uninformed and irresponsible. You didn't seem to research this book or the line that it is a part of. The entire All Time Comics universe is written by Josh Bayer who is a lauded and prolific figure in underground comics. His work has been mostly self-published and this series on Fantagraphics represents his most high-profile release to date.

Josh's work is steeped in reverence for the "paid by the page" writers of the early comics industry. Usually he does his writing, art, including pencils, ink and color and publishes himself. But with this universe he wanted to create a homage to the Marvel-style Bullpens of a different era. This with the goal of employing some senior and upcoming artists that collaborate to make a finished title. Each All Time Comics release, all set within a universe and continuity in which there are so far four superheroes and dozens of auxiliary characters, has at least two alternate covers by different artists, a different artist who does pencils, another that does inks, another lettering, another that does colors with Josh as writer/editor and Fantagraphics as publisher.

This collaborative effort is a tribute to the sometimes amazing and sometimes grotesque work that came out of the comics industry in its early days. So when you write this review and call it "useless", "none of it matters", "there is no point", "the first out and out failure in a decade" etc... you are doing so at the expense and in apparent ignorance of the intent of the comics line which is to honor the collaborative, working-class, sometimes assembly-line approach to the classic comic tradition that made "underground comics" and graphic novels possible.

So my question is: "Why do you hate comics?" This and the whole All Time Comics line is a labor of love by people who have lived and breathed comics for their entire lives. In fact, Crime Destroyer, Part of the ATC series, was the final work of comic veteran Herb Trimpe who loved the work being done and said he felt honored to be working with All Time Comics. All Time Comics could be the beginnings of a line that has some longevity and ability to create some more great work and employ artists and writers for some time to come.

For you to outright condemn ATC without context harms that possibility but perhaps more importantly to you, it comes across like you didn't do your homework and need to take a comics history and appreciation course. The review reminds me of music reviews by writers that couldn't wrap their heads around Bob Dylan going electric, The Clash doing reggae, Devo, Elvis, Stravinsky, Shostakovich or any tradition-bucking work. The review ultimately comments more on you and your lack of historical context for this type of work...and I would say feels like it is dripping with the type of contempt you accuse Atlas #1 of having.

I guess the real question is: What is the intent of this type of review? To express your contempt for the artists and writers or the type of people that would read this kind of "ugly" work? It feels like both of those things which is why I said the review felt irresponsible. You insult a hypothetical audience you don't understand when you "can’t imagine the circumstances that would allow someone to enjoy this kind of thing." But really, I'm honestly curious, what is the intent of this type of review?

Sincerely,

Joaquin

Hi Joaquin,

First of all, thanks for writing! I’m always happy to read thoughtful feedback from readers. Your email brings up a lot of important questions about my responsibility as a critic — something it’s really important to investigate on a regular basis.

So let’s start with context. I am aware of the backstory of the All Time Comics line. (I said it looked like “a lot of fun” when it was announced seven months ago). I know who Josh Bayer is, and I’ve been reading Herb Trimpe’s comics since I was a little kid in the early 1980s. Though I have no doubt he was a nice guy and a consummate professional, Trimpe’s work has never done anything for me, particularly his Liefeldian reinvention in the 1990s, which I found to be spectacularly ugly.

So the question your email raises for me is: is it my responsibility to provide background and context for everything I review? I don’t think so. Reviewers aren’t doing PR for publishers and authors. It’s not our job to explain the intent behind the book. It’s our responsibility to share our opinion about what’s on the page.

When I write my comics column, the question I often have in my mind is: if someone picks up this comic with no prior knowledge, what will they think of it? Because frankly, if someone needs to understand three paragraphs of backstory before they can enjoy the first issue of a comic series, that comic series isn’t doing its job. Serialized comics — the sort that Atlas is supposed to be mimicking — need to be as accessible as possible to new readers; if all that information you gave me was essential to enjoying the comic, it should’ve been included in the comic.

I’ve been reading comics my entire life, and I was a teenager in the late 80s/early 90s, which is the era that All Time Comics seems to be emulating. Even at the time, I wasn’t much of a fan of the assembly line style of comics production. (I gave up on Lee/Liefeld comics when I accidentally bought the same issue of the X-Tinction Agenda crossover twice in two weeks because the cover was so bland and forgettable.) So admittedly, I’m probably not the target audience for All Time Comics. (But I’m not alone in disliking mainstream comics from the 1990s; it’s more than a little weird that Fantagraphics is trafficking in nostalgia for comics that they openly mocked as garbage the first time around.)

The most compelling argument you make for All Time Comics is that it provides money and opportunity for comics veterans who have been forgotten by Marvel and DC Comics. But why did that money and opportunity have to come in the form of a rehash of their earlier work? Why ceremoniously load them back onto the corporate comics hamster-wheel? Why not ask them to do something new? I would’ve loved to see what comics Herb Trimpe might have made if he was offered carte blanche by a comics publisher; instead, he just rehashed some of the worst work of his career.

As to your argument that I’m the equivalent of a critic missing out on Dylan going electric: I mean, that risk comes with the job. (I am not a Bob Dylan fan, so I expect I wouldn’t have had an opinion one way or the other about him going electric.) It’s not a critic’s job to be “right” 100 percent of the time. Hell, here’s a little secret: when it comes to art, there is no right or wrong. Your opinion, Joaquin, is just as valid as mine. Isn’t that awesome? I think it’s pretty awesome.

But there is a line from the column that I regret, and I want to thank you for giving me the opportunity to address it. I could even tell that I wasn’t happy with the line when I was writing it, but the deadline was breathing down my neck and I let it slide. Here it is: “I can’t imagine the circumstances that would allow someone to enjoy this kind of thing.”

To me, that sentence crosses a critical line. It’s not my job to worry about whether you like the book or not, or how you like the book, or why you like the book. It's not my job to speak for you, or any other fan. In that sentence I was expanding my agency beyond myself and putting it into an imagined readership for the book. I was giving myself more power than I have, and that was an unfair thing to do in a review. I wish I hadn’t included that line.

But as to everything else? Yeah, I stand by it. I think Atlas was an ugly, poorly written book. I do think it’s the worst thing Fantagraphics has published in years. I would not recommend it to anyone.

At the same time, Joaquin, I’m happy that you like the book, and that you cared enough about it to start a conversation with me on its behalf. I’m especially thrilled that you decided to stand up for the art that you believe in. This back-and-forth is exactly what criticism should be about. Thank you for that reminder.

Warm regards,

Paul

Thursday Comics Hangover: A womb with a view

Tomorrow, Tatiana Gill will release her new comic Wombgenda at the Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery as part of the Comics & Medicine Conference. Over the last couple of years, Gill has become one of Seattle's best, and most prolific, autobiographical cartoonists, and Wombgenda collects some of her latest work — most of it related to women's health, but with some current events mixed in.

The three long pieces in Wombgenda address Gill's journey to developing a positive body image, her abortion story, and an account of getting a new IUD at Country Doctor. Her style in these strips is very reminiscent of Seattle cartoonist Roberta Gregory's autobiographical comics from the 1990s — simple figures, little to no backgrounds, and a lot of words packed into every panel. They feel something like handwritten letters from a friend — confessional, intimate, exuberant, and heartfelt.

Most of Gill's stories are about discovery: learning she's not alone, figuring out what to do to solve a problem, looking into the basic day-to-day processes of a doctor who specializes in women's health. If you are a woman wrestling with body image issues, or unwanted pregnancy, or other health issues and these comics land in your hands at just the right moment, they could easily be the most important comics you'll ever read in your life. If you are not any of those things, Gill's specificity — her confident voice and strident curiosity — can help put a face on an issue in a way that might change your perspective. And isn't that what non-fiction comics are all about?

The other material in Wombgenda mostly hews to political spot illustrations drawn from the tradition of American World War II propaganda posters. (I like the one of Lady Justice and Lady Liberty flipping a rich guy's chair over with the caption "Let's work together and overthrow the patriarchy.") She also includes a page of love notes to cartoonist women from Seattle who influenced her, giving the comic the air of a 1990s fanzine.

Maybe one day, Gill will get a fancy book deal from a big New York publisher to do a graphic memoir and she'll disappear for a few years while she works on her magnum opus. But for now, we're lucky to have her out in the streets of Seattle, attending our protests, telling the stories of women, capturing everyday life in a city that's always changing. She's telling this city's stories, and we're lucky to have her.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Is this the ugliest comic in the world?

I just bought it last night, but I'm pretty sure that Atlas #1 is the ugliest comic book I own. Only the cover, a sensitive piece by Anders Nilson featuring the titular hero holding a charred corpse while floating in a smoggy yellow haze, is aesthetically pleasing.

But flip past the cover, and the rest of this book is ugly as sin: the coloring is garish and sloppy, the art style is childlike and aggressive, and the writing is opportunistic and so drenched in irony that it's impossible to tell if it's a joke, or a joke about a joke, or if it's supposed to be taken entirely straight. But the worst part of this ugly book is that it's published by a press that makes some of the world's most beautiful books — Seattle's own Fantagraphics Books.

Atlas is part of Fantagraphics' All Time Comics initiative, a nostalgia line intended to evoke the Marvel and DC Comics of the mid-1980s. All Time has even hired many of the creators from that time and put them back to work drawing books. Even the "ads" for Atari 2600-style video games on the back cover look like they were originally published in the 80s.

But the book is positively dripping with contempt. Is it contempt for the audience? For the mainstream comics that inspired the All Time line? For the superhero-infested popular culture around all of us at all times? Unclear. The contempt seems to fly in all directions. Nobody is clean.

There's no point trying to explain the plot of Atlas. A superhero strikes a congressman in public and is then sent to jail. Meanwhile Atlas's friends are being burned alive. Somebody has to pay. Atlas pretends to be the center chapter in a long, ongoing superhero story, with an imaginary continuity stretching back decades.

But the truth is, none of that matters. The only noteworthy thing about Atlas #1 is how ugly it is — how offensive it is to the eye. Everyone's anatomy is misshapen. Panels frame grimacing close-ups and the dialogue strains against itself on every page:

Tobey! No!! You stupid kid!! What have you done?! I can't protect you in this godforsaken place! I can't even help myself right now! Tobey could DIE here! ANYTHING could happen. He doesn't know WHAT kinds of MONSTERS we're locked up with!

It's all like that: clunky and hammy and willfully dumb. I can't imagine the circumstances that would allow someone to enjoy this kind of thing. Sometimes Fantagraphics' reach exceeds its grasp, but this is the first out-and-out failure I've seen from them in over a decade.

Thursday Comics Hangover: True colors

The future of comic books is not superheroes; it’s young adult fiction. If you look back on the last fifteen years or so of popular comics bestsellers, it’s pretty easy to track the direction of reader and creator interest, from Mark Millar to Bryan Lee O’Malley to Faith Erin Hicks. It’s not as big a shift as, say, the death of the western novel, but it’s definitely there: whereas comics used to be serialized monthly to large and eager audiences, we’re seeing more and more trilogies starring young characters (mostly girls) released in large chunks once a year or so.

The latest example of the YA push in comics is Spill Zone, a sci-fi adventure comic written by Scott Westerfeld and illustrated by Alex Puvilland. Westerfeld, a bestselling YA novelist, has clearly done a lot of thinking about how to tell a story with comics: the world-building in Spill Zone is elegant without being overly expository.

Recently, an accident tore a hole in reality in the middle of a town in upstate New York. The authorities did all the usual things they do in case of a disaster: call in the military, cordon off the affected area, and keep the looky-loos away. But while the disaster isn’t spreading, it’s not going away, either. An aura of normalcy has crept back in to the situation.

Meanwhile, a young woman named Addie has been going on excursions into what’s now called the Spill Zone. As imaginative as Westerfeld’s descriptions of the Spill Zone might have been, credit must go to Puvilland for bringing those descriptions to the page: this is not your standard “weird” comics land, where all the monsters are brown and lasers fly around in the background. The Spill Zone feels like a land where anything is possible: step in the wrong place and you become 2D. Turn the wrong corner and an abstract expressionist wolf might eat you. Get too close to the mandala constructed out of floating bowling pins and ... well, who knows what’ll happen?

But a great deal of the credit for Spill Zone’s eeriness must go to colorist Hilary Sycamore, who renders the otherworldly neighborhood in flat, ugly colors that would not seem out of place in a 1970s kitchen. These olives and burnt umbers and swirling urine-yellow tendrils make it so a reader can flip through the book and tell with just a glance which parts of the story take place in the real world and which happen in the Spill Zone. It’s not a flashy coloring choice — one blanches to think what an early-2000s colorist drunk on computer effects might have done — but it’s brilliant. The comics business is full of great colorists right now, but Sycamore has to be one of the best.

Of course, since the next volume in Addie’s story won’t be published until next year, it’s impossible to determine whether Spill Zone is the great start of a great story or the promising opening chapter of a dud. But in terms of sheer world-building bravado and technical prowess, this book is worth your attention, as full of energy and imagination and enthusiasm for the comics form as any superhero comic I’ve read in the last few years.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Rolling the dice for charisma

It's a kind of nerdception: Rise of the Dungeon Master is a biography of Gary Gygax, inventor of Dungeons & Dragons, told in comic book form. Writer David Kushner and artist Koren Shadmi do excellent work transforming what could be an incredibly dry subject — Gygax's slow construction of Dungeons & Dragons from pieces of miniatures-based military reenactment games — into a breezy biographical story. Rise is a book that shouldn't work, for several important reasons.

It's told in second person. While just about any writing instructor would urge a biographer to not write a book with "you" as a subject, second-person works here because it follows the format of a Dungeons & Dragons game. ("Your mother also fills your imagination with adventure," the captions inform Gygax like a Dungeon Master equipping a player for an oncoming battle, "she reads you Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn.")

Shadmi's art is very cartoony. Realism isn't necessary for a biography — Peter Bagge, with his rubber-armed figures, has somehow become one of our best comics biographers — but the mundanity of Gygax's upbringing and the gaudy muscularity of Dungeons & Dragons would seem to call for realism. Instead, Shadmi's likenesses, with their big, rounded Disney faces and their exaggerated poses, somehow add to the familiarity of Gygax's story, making him more relatable.

There's not too much of a narrative arc. The story follows D&D's meteoric rise in popularity and its controversial period in the 1980s when it became associated with Satanism and juvenile delinquency, but generally not too much happens in the story. Gygax is a dedicated process nerd who invents the game, and it quickly becomes an American standard.

Despite these seeming drawbacks, Rise works on multiple levels. Kushner ingeniously compares D&D to an operating system, and that metaphor instantly gives the story of the game a more familiar shape. At this point in the 21st century, we know the story of the successful Silicon Valley startup by heart, and that tech creation narrative lends its own drama to D&D's history, adding a friction that other accounts of Gygax's life don't really enjoy.

One major flaw of Rise comes in a choice with the book's lettering. The second-person narration captions are the same basic shape as the captions that contain Gygax's quotes, often leading to a confusing mishmash of perspectives, switching back and forth from "I" to "you" without much of a visual difference besides some ragged caption borders. A stronger visual cue, such as putting quotes in rounded word balloons rather than square ones, would make for an easier, less-muddled reading experience.

But aside from a few stumbles caused by that muddled narration, Rise is a chatty book that neither wallows nor sidesteps its subject's inherent wonkiness. D&D nerds and novices alike can find new information here. It's a miracle of explanatory storytelling, and it builds to a climax that is artful and genuinely affecting. This biography is more than just a series of things that happened — it's a celebration of a genuinely new invention that changed the course of history.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Wonder Women

I haven’t had much to say about superhero movies lately — sorry, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, it’s not you, it’s me — but I do agree with the consensus that the movies made from DC Comics superheroes have been disastrous. Batman V Superman was one of the worst blockbusters I’ve ever seen. Suicide Squad was even worse. I’ll be watching the Wonder Woman movie when it debuts at Cinerama in a couple of weeks, but that feels more like an act of obligation: I want to support the first female superhero movie in a generation, even though Gal Gadot has never once ever successfully, in the technical sense of the word, acted.

The most confusing thing about the failure of DC Comics to transition to film is that there’s already a perfect prototype out there for the producers to emulate: Melissa Benoist’s performance in the weekly Supergirl TV show. In the 80s and 90s, superhero movies were always trapped in a tug-of-war between the two opposing poles of dark-n-gritty (think the first Tim Burton Batman) and campy (think the Joel Schumacher Batman Forever). Benoist’s performance as Supergirl finds a new, third way: she’s earnest but serious, happy but determined. Sure, the effects on Supergirl are cheesy, but even when it’s at its worst, Benoist’s performance holds the whole damn show together.

DC’s stable of characters — more colorful and goofy than Marvel’s — should more or less follow Benoist’s lead. These are over-the-top sci-fi concepts from the 1950s; the concern is not taking them seriously. It’s about believing in their character. Benoist gets that. The people adapting DC Comics to film, sadly, don’t.

The new collection of Supergirl comics from DC, Reign of the Cyborg Superman, unfortunately, doesn’t have Benoist’s charm, either. To the credit of writer Steve Orlando and artists Brian Ching, Emanuela Lupacchino, and Ray McCarthy, they’re rightly shooting for the optimism and the youthful vivaciousness of the TV show. Unfortunately, the comic is kind of a mess.

Reign establishes a world that mimics the basic status quo of the Supergirl TV show, introducing characters and situations that viewers will find very familiar. But it feels kind of like a mess, with some occasionally lively artwork obscured by Michael Atiyeh’s muddy coloring, and a plot that tries too hard to emulate the ALL CAPS APOCALYPSE feel of a superhero movie. The villain of the piece — Supergirl’s father, who for some reason looks like a cyborg Superman — is way too broad. But to Orlando’s credit, the book ends on a high note, with Supergirl nailing the hope and courage of her TV version. And thankfully the art doesn’t objectify Supergirl with the leering 90s male gaze that has dogged the character over the last couple decades. There’s room for improvement here.

But Supergirl isn’t the only female superhero DC is publishing these days. They’ve also got a new Superwoman character, and her first adventures are collected in a new paperback titled Who Killed Superwoman? While Supergirl is Superman’s Kryptonian cousin, the stars of Superwoman are two of superman’s love interests: Lois Lane and Lana Lang, who have both been given powers somehow — it’s not important — and who are teaming up to cover for a seemingly deceased Superman’s absence.

In case you can’t tell, there’s a lot of continuity at play in Superwoman, but you don’t have to read a dozen other books to understand what’s going on here. Writer Phil Jiminez takes a delightfully old-school approach to his superhero comics: he welcomes the weirdly intricate decades-old relationships between characters, but he also explains the important stuff to the readers in the course of the story. It’s accessible, while still hinting at the sixty years of backstory available to curious readers.

Without giving too much away, the story introduces a couple of villains unique to the book while addressing the question of what it means to do the right thing, even if it kills you. Emanuela Lupacchino’s art is better-served on this title than on Supergirl, giving her time to invest emotionally in the characters and better frame out the surroundings. Jiminez draws several issues himself in his tight, George Perez-style 80s superhero comic style. For people who’ve been reading comics for decades, it’s a throwback delight that somehow still feels like a modern superhero comic. It’s also my favorite Superman-themed book that DC has published in years, an operatic riff on values and expectations and responsibility.

DC is also publishing the original female superhero, and I’m happy to report that the second paperback of Wonder Woman comics is terrific. Just in time for the movie, writer Greg Rucka and artist Nicola Scott have told an origin story for Wonder Woman that audiences will find to be compelling and modern and fun. (Yes, even though there’s a number “2” on the spine, Year One is an origin story and can be read on its own. Sometimes comics are dumb.)

Generally, I’m against retelling origin stories in comics; my philosophy is just murder the parents in a flashback and get on with the story. But Wonder Woman has needed a good origin story for just about her entire life as a character, and Rucka succeeds where so many others have failed by making her eminently relatable.

Yes, this Wonder Woman is wildly powerful. Yes, she bests all of her fellow Amazons in hand-to-hand combat. But she’s also a total nerd, and when she first comes into contact with our modern world she can’t speak English, which gives her a relatable vulnerability. When she goes to a mall, she’s overwhelmed by all the sights and sounds and smells. (She asks a translator, “Why does the air taste this way?”) She’s tough and curious and exuberant, expecting the best and preparing for the worst.

Scott is a gifted superhero artist. She can capture difficult emotions like a flicker of nostalgia on a person’s face, but she can also draw an iconic double-page spread of Wonder Woman, her blurry arms spread out around her, octopus-like, as her bracelets deflect bullets at super-speed. Scott often draws her from below, to cast her in a heroic light, and this simple trick doesn’t feel at all manipulative or cheap; Scott conveys the sense that she’s genuinely in awe of the character she’s drawing.

A lot is riding on the Wonder Woman film. In addition to its unique status as the first-ever female-starring superhero film of the modern era, it’s also the first to be directed by a woman (Patty Jenkins, director of Monster) and the last DC superhero film to be released before this fall’s team-up film Justice League. But even if the film is a disaster — by artistic standards, by box office standards, or both — Year One proves that the character of Wonder Woman will survive. There’s a lot of humanity yet to be explored.

In which SRoB readers recommend comics cookbooks to me

Yesterday, I wrote that comics and cookbooks go together as perfectly as bread and butter. I also pointed out that no publisher has put together a truly great, comprehensive comics cookbook. In comments on Facebook, though, a few readers pointed out that there are some more comics recipes out there for you to enjoy.

Chris suggested Tyler Capps's weekly comic strip Cooking Comically. I hadn't heard of this one before. Capps uses a blend of photography and comics to lay out his recipes. I'd appreciate a little more cartooning in his strip — the process could be slightly more stretched out and explained more thoroughly — but it's a neat blog and I happily subscribed to it.

Queen Anne Book Company bookseller Tegan recommended a vegetarian cookbook called Dirt Candy, by Amanda Cohen, Ryan Dunlavey, and Grady Hendrix. This one looks like a graphic novel. Here, from the Dirt Candy website, is a sample of a couple pages:

Now, maybe this will make more sense once I actually look at the book. But I don't understand why you'd have a whole book told in comics form and then switch over to prose for the recipes before switching back to comics again. Still, I'm excited to check this book out! I'm not a vegetarian, but I do love to cook and eat vegetarian meals, and this book looks like an interesting hybrid.

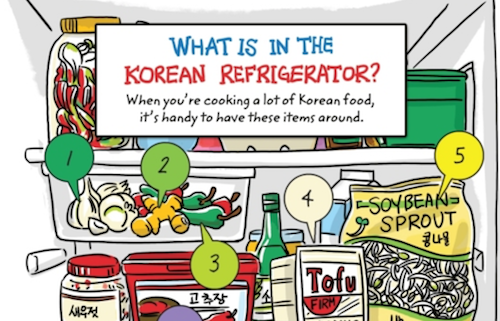

And Alex said that Cook Korean! A Comic Book with Recipes by Robin Ha is getting great reviews. This one does look very close to my idea for a good comics cookbook. Get a load of this chunk of a full-page spread showing off a Korean refrigerator (The next page in the book explains what everything is:)

While none of these three recommendations quite fit the bill of what I was talking about in my post, they're certainly very close, and they demonstrate that people are playing around with the form. I think this proves that the field of cookbook recipes is rapidly advancing, and one day soon I will have my dream book on my cookbook shelf.

Most importantly, thanks to Chris, Tegan, and Alex for the tips! These are all great recommendations. I'm excited to have a new weekly cooking blog to read, and the next time I'm out I'll definitely check out these two books. If I have any thoughts on Dirt Candy or Cook Korean! after checking them out, I'll share them here. And if you have any other recommendations, please feel free to drop us a line on Facebook.

UPDATE 10:55 AM: And in the Facebook comments to this post, Seattle cartoonist Colleen Frakes writes:

The Trees & Hills Comics Group has put out a couple of comic anthologies about food/recipes, one was "Seeds" (that one had my egg drop soup recipe. I cook a lot of soups) and the newer one is called "Sprouts". Saveur was also running comic recipes for a while.