Archives of Thursday Comics Hangover

Thursday Comics Hangover: How to get the most out of your Free Comic Book Day

Ordinarily, I use this space to write about the comics that I've read over the past week. But this Saturday is Free Comic Book Day — that nationwide celebration of the belief that there's a comic out there for everyone — and so we're going to look forward for a change. If you've never participated before, you should know that it's pretty simple: walk into the store, get some comics for free. If you have questions, ask the staff.

Where should you go? Well, there's a map of all the participating shops here. But a lot of local stores are throwing special events, too. A partial list:

Comics Dungeon in Wallingford will be hosting local cartoonists all day. I spoke with the Dungeon's owner Scott Tomlin about his plans — and the exciting new literacy nonprofit behind his shop — earlier this week.

From 11 am to 3 pm, Phoenix Comics and Games on Broadway will host Seattle comics writer G. Willow Wilson — who was recently the subject of a terrific New Yorker profile and the driving force behind a very good conversation about faith on the Ezra Klein Show — along with cartoonist Kazu Kibuishi and author/translator Zack Davisson.

Downtown's Zanadu Comics is throwing a big sale and handing out special coupons all day long. If you regularly buy comics in Seattle, you should stop by Zanadu and buy a comic or two; the store has recently fallen on tough financial times and they've been running a GoFundMe to stay afloat. They've still got some of the best selection in town, and they could use a little love.

Arcane Comics, which last year moved just across the Seattle border to Shoreline, is hosting local cartoonists Jen Vaughn, Chris Sheridan, and Tatiana Gill.

There are plenty of other shops, too, including Fremont's Outsider Comics & Geek Boutique, the Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery in Georgetown, Dreamstrands Comics & Collectibles in Greenwood, Golden Age Collectibles in the Pike Place Market (which I just now learned from their website claims to be America's oldest comics shop,) and The Dreaming Comics & Games in the U District.

And what should you pick up? Well, you can find a full list of the Free Comic Book Day books here, and there's something for most everyone's taste. But here are a couple to look out for:

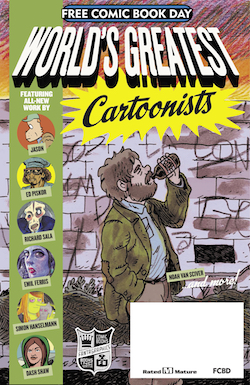

Obviously, you should read the Fantagraphics collection World's Greatest Cartoonists, which features a bunch of artists from the Fantagraphics stable including Emil Ferris, Noah Van Sciver, and Simon Hanselmann.

If you're unfamiliar with the weird and wonderful collaborations between French cartoonist Moebius and the great director Alejandro Jodorowsky, this sampler of their comic The Incal should definitely be on your list.

The Colorful Monsters collection has just about everything a kid could want, including some Moomin comics, monsters, and hot air balloons.

Cartoonist Kate Beaton loves the all-ages comic Bad Machinery, and this sampler is a good introduction to the series, about some young crime-solvers. In this caper, they encounter Communists and a very anachronistic person.

Have fun out there! Stay hydrated, get some free comics, maybe buy a comic or two, and follow along with us on Instagram as we travel around to some of our favorite shops.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Lost in space

Not so very long ago, if you were a kid and you wanted to read comics, you had a couple of choices: you could either read superhero comics, or you could read Archie comics. Now, the young adult comics scene is positively thriving. Teens can find realistic comics, fantasy comics, sci-fi comics, adventure comics, and romance comics in just about any comic book store.

In the last month, Image Comics has released a pair of new YA books that demonstrate the breadth and depth of the field. These direct-to-paperback books are a bit of a departure for the publisher — unlike most of Image’s output, they weren’t originally published in monthly serialized format — but hopefully they represent a new initiative for Image, because they’re excellent examples of the form.

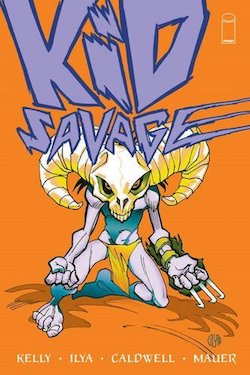

Kid Savage, written by comics veteran Joe Kelly and illustrated by the one-named and all-capped ILYA, is the most plainly high-concept of the two. It’s basically the family from Lost in Space if they adopted a pint-size Tarzan on their travels, with a reality-show twist. This volume is essentially an origin story, crashing the family on a primitive planet and pitting them against (and eventually alongside) the titular wild human.

Kid Savage is an appealing package. ILYA’s art is dynamic and expressive, with lots of bold lines and nuanced facial expressions from all the characters. (A couple of the action sequences, however, are very difficult to follow.) And Kelly does a fun tweak on the father-knows-best convention of traditional sci-fi by making the father of the spacefaring clan a bit of a hand-wringing boob who’s plagued by self-doubt and riddled with guilt. The son and daughter are forced to be the adults because the mom’s out of the picture, but that dynamic is immediately set into doubt when they run across a character who is basically nothing but raging id. It’s a good start to what is hopefully a series of sci-fi survival adventures.

The other book from Image, Afar, defies easy description. It’s about a brother and sister in a post-apocalyptic society, but it’s not another example of the dreary survivalist yarns that have taken YA hostage over the last decade. The sister, Boetema, discovers that she has a fascinating power: when she sleeps, her consciousness comes to life in the body of an alien, somewhere else in the universe. Boetema inhabits the consciousnesses of beings like her (a humanoid race in an advanced civilization) and not like her (a squidlike creature wrapped in a sack at the bottom of a fishing boat) and she seems to have no ability to control what world she finds herself on next.

Afar is a cosmic space fantasy that also incorporates a complex political dynamic as the siblings try to survive in a punishing desert culture. With her head in the stars, Boetema finds it more and more stressful to take care of her brother while also intermingling her consciousness with alien cultures halfway across the universe. It’s a perfect read for those kids who are perennially daydreaming, because it’s a story about what you can do when you allow your mind to wander.

Young readers will find the story, by Leila Del Duca, to be dense and rewarding. But the art by Kit Seaton is what will draw people in. Seaton is adept at conveying the ideas behind entire alien civilizations in just a handful of panels, and her skillful use of color and perspective keep Boetema’s “dream”-life clearly delineated from her “real”-life. There’s never any doubt where we are in the story at any point, which is a testament to Seaton’s ability to keep a reader grounded in a story that briefly features a planet of wizard-dogs.

This is the kind of book I wish I’d found in a school library when I was 15. Afar doesn’t just give readers a new, alien world; it introduces readers to ten of them, and inspires them to wonder about all the possibilities out there in the great big universe.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Out of left field

Yesterday, I was planning to pick up the first issue of Secret Empire, the new Marvel Comics crossover. (Technically, it was issue #0; the first issue of Secret Empire — as in the issue marked "#1" — is due on May 3rd. If you're already confused, I apologize for what I'm about to put you through.) Every once in a while I like a big superhero crossover if it's handled well, and I enjoyed Nick Spencer's run on Ant-Man a while ago. Seemed worth a shot. But then I saw this tweet by Marvel editor Tom Brevoort:

A quick semi-word of warning for this week's books: the three Opening Salvo issues are meant to be read before Secret Empire #0.

— Tom Brevoort (@TomBrevoort) April 18, 2017

And because of that tweet, I didn't bother to pick up Secret Empire #0. If the first issue — sorry, the zero issue — of a series requires a "semi-word of warning" that three other books should be read beforehand, I can't really be bothered.

Look, I appreciate that superhero comics are a serialized storytelling medium. The minute a story has a conclusive ending, there's no reason for readers to pick up the next installment. But I do expect a story to make sense in and of itself, with a beginning, a middle, and some semblance of an ending. If the beginning of a book requires advance reading, it's not really a beginning.

Or let me use another example from a different publisher. I found the first collected volume of Detective Comics from DC's Rebirth line, Rise of the Batmen, to be a lot of fun. It's basically a Batman superhero team book, in which Batman must assemble a team including the formerly villainous Clayface and three interesting female characters from other Batman-themed books — Batwoman, Spoiler, and the Orphan (who used to be Batgirl) — to fend off an insidious Batman-themed threat.

Rise of the Batmen is mostly a good example of serialized superhero comics done right. The bad guys have a clear motivation, the heroes all have distinct personalities, and it's all terrifically, deliciously silly. Sure, it's a bit too goth — it is a Batman comic, after all — but it's brisk and entertaining and it never takes itself too seriously.

But then comes the ending. One of the characters supposedly dies. But then a page or two later we find out this character — gasp — didn't die after all! Par for the course for superhero comics. Except the character didn't die because they were plucked from the death scene by someone in another dimension or something, a bad guy who had nothing to do with the rest of the book.

Presumably, this plot device is setting up a crossover in some other, future DC Comic further down the line. But if you're reading this book as a book — which is to say you're expecting it to have a beginning, a middle, and an end — you're going to be incredibly disappointed. This isn't a fair ending. It's not a surprise, or a twist. A reader couldn't be expected to know what the hell is going on here without reading a ton of other comics. It's not even a deus ex machina; it's a non sequitur.

I love the fact that superhero comics never end, but I hate the fact that superhero comics are now absurdist echoes of themselves. Comics in the 60s and 70s and 80s used to catch readers up and explain the intricate mythologies behind the characters along the way. I understand that fashions change, and that the exposition-heavy comics from decades ago now read as impossibly clunky.

But surely there must be some way to convey the dense mythology of superhero comics gracefully? One thing comics are great at is broadcasting a lot of information in a relatively small amount of space. Modern superhero comics are all about withholding information, and demanding that the reader invest in dozens of books in order to understand what's going on. This philosophy is not only anti-new-reader; it's anti-comics.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The unhappiest children's books in the world

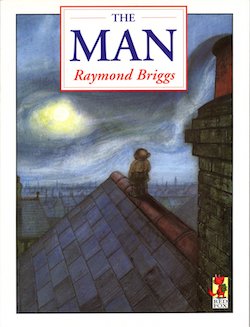

Like so many of the best books, I found it hidden behind a couple outdated computer programming manuals in a Goodwill. It’s a tall, slim hardcover book with a torn dustjacket. The cover is a soulful color sketch of a tiny figure standing on a roof staring out at a cloudy night sky. It says in big letters at the top, The Man, and below that, in smaller print, the author credit: Raymond Briggs.

You likely know Raymond Briggs for his wordless children’s book The Snowman, but Briggs has a long and colorful publishing history. He’s written and drawn dozens of books, and he’s been publishing from the 1960s to, most recently, 2015. Many of his books — including The Man — are out of print in the United States.

Because they deal almost exclusively in the interaction of words and pictures, most children’s literature is, in some form or another, comics. But Briggs’s work shares more of a common vocabulary with modern comics than most other authors for children. His books have multiple panels per page, and dialogue often depicted in word balloons, and the work features other comics traits that you don’t find in more “traditional” kid’s lit.

The Man, though, is a little bit of a departure for Briggs in format: the book features experimental layouts — often with one large illustration per page and dialogue typed out, in different fonts for each character, down the middle of the page. It’s less like a comic and more like a stage play. The book keeps its scope fairly intimate, too: it’s the story of a young boy who, one day, finds a bossy little naked man living in his room.

The man, who only answers to Man, demands that the boy fashion him some clothing out of an old sock and a rubber band, and then he proceeds to complain even more: “I wish you had real marmalade,” he whines when the boy smuggles some food up to him. When the boy wonders aloud if Man is a Borrower, he angrily spits, “Pah! Stories! I hate them.”

Man’s continual insistence quickly grates on the boy, and they begin to fight. “You exploit your smallness,” the boy yells at Man, “You know how to use it. You manipulate people by it. You manipulate me for your own selfish ends.” Man retorts, “You make out you are being kind, generous and caring when all you are doing is using my smallness for your own ENTERTAINMENT. You don’t care for me as a PERSON! To you, I’m just an entertaining NOVELTY!”

The Man’s tone is all over the place: it’s hilarious, and tense, and realistic, and more than a little upsetting. But it finally settles on a deep and melancholic sadness that speaks to the sacrifice we offer to others: even those we love most — those tiny people who show up naked and willful — can get on our very last nerves, and sometimes we lash out in uncomfortable ways. That’s a special kind of sorrow. The last page of The Man speaks to a sadness that I’ve never quite seen represented before in children’s fiction.

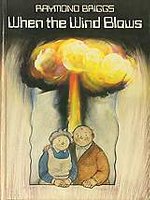

Briggs is no stranger to uncomfortable topics. Another of his out-of-print classics, When the Wind Blows, is, if anything, even more depressing than The Man. Wind is the story of an old British couple living in the countryside. They’re not especially deep or introspective people, but they’re law-abiding citizens who seem to enjoy each others’ company. One day, there’s an upsetting story in the news reports: nuclear war is breaking out.

A bomb drops not far from the couple, but far enough away that they’re not killed in the explosion. So they set about doing what any rule-following British citizens would do: they build a makeshift shelter in their home and they hunker down “for the 14 days of the National Emergency.”

Everything around them collapses — the radio stops working immediately and the nearby town’s supplies are wiped out soon after the first hit — but they continue living their lives: the wife wraps pillows in their shelter in plastic because “I don’t want finger marks getting all over them.”

Like The Man, Wind does not have a happy ending. Unlike The Man, Wind is well and truly apocalyptic. The couple start showing signs of radiation poisoning, but they still trust in the rules. “We’d better just lie here and wait for The Emergency Services to arrive,” the wife says. “Yes, they’ll take good care of us,” her husband replies as they huddle in potato sacks for warmth. “We won’t have to worry about a thing.” Those institutions will not save them. It’s dark. Really dark.

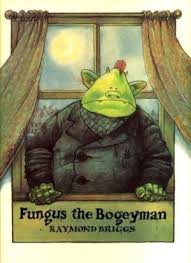

While not as bright as The Snowman, Briggs’s Fungus the Bogeyman is considerably lighter than either The Man or Wind. It’s the story of a bogeyman community that treasures the opposite of everything our society adores. Fungus’s wife wakes him at dusk on the first page of the book. “Time to get up, Fungus my dreary. It’s nearly dark.”

Fungus wakes up complaining: “OOOH! What a night that was! This bed has almost dried up!” His wife agrees, “I know, drear. It needs more slime.” Fungus walks over to a bin filled with cold water and pulls out his clothes for the day. A caption helpfully informs us, “Fungus inspects his trousers which have been marinading overnight." Fungus, his face inside a pair of pants, exclaims approvingly, “Mmmm! These really stink!”

Bogeyman follows Fungus through a typical day in his life. Throughout the book, captions explain Bogeyman culture, from the fact that they “cultivate boils on the back of the neck” to an account of the rotten grapefruit and “mouldy” cornflakes they eat for breakfast.

As an artist, Briggs is having a lot of fun here, experimenting with wild panel layouts and exaggerating the moribund dreariness of bogeydom culture. The expressionless dot eyes and upturned pig noses of his bogeymen give them a cartoonish appeal. It’s easy to imagine children falling into this book and being swept up in the many shades of sick-making green on every page, wondering at the intense oppositeness of Fungus’s world.

The best part of Bogeyman is how normal it all is. While Wind feels like a scathing refutation of humanity’s ability to remain docile in the face of global Armageddon, and while The Man revels in the way it upturns societal commitments, Bogeyman takes a sort of pleasure in the everyday rituals and cozy domesticity of its main characters. It’s unique in all of Briggs’s work in that it finds a sort of peace in its miserableness. It’s okay to be unhappy, Bogeyman says, as long as you’re okay with being unhappy — and don’t let anyone spread sunshine on your rained-out parade. It’s your party. You can cry if you want to.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Queen of the wild frontier

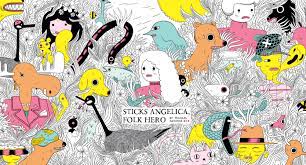

Michael DeForge’s new book Sticks Angelica, Folk Hero begins with all the elements of a classic comic strip. You’ve got the flawed main character, Sticks Angelica, a know-it-all chatterbox who, feeling underappreciated by society, moves to the wilderness to be alone. She fancies herself a survivalist: “I run twenty kilometres every morning. On days I don’t bathe, I rub flowers on my armpits.” And she claims to live the life of a folk hero, wrestling bears when she’s bored and devising homeopathic cures for hangnails.

And then there’s the supporting cast: you’ve got assorted talking animals to keep her company, including a rabbit named Oatmeal who harbors a massive unrequited crush on Sticks. (“How I long to nibble on her earlobe; to eat a carrot out of her hands; to have her carry me into a shared room, which we decorated together.”) Her social circle includes a moose named Lisa Hanawalt who is not to be confused — or, hell, probably she is to be confused — with the cartoonist of the same name. In the background, you’ve got a chorus of simple-minded geese who run around haranguing each other. (“…But we’re geese. Not — not coyotes. Geese are supposed to be Canada’s most trustworthy creatures,” one scolds the other when they accidentally murder a fish. The other replies, “That’s just propaganda from the goose lobby.”)

It even looks like a comic strip collection: Sticks Angelica is laid out in a series of single-page gags, many of which made up of eight panels. For a while, the last panel on every page has a punchline centered around the characters, like, say, Garfield or Dilbert. And unlike those two comics, Sticks Angelica is actually funny.

But then Sticks Angelica starts to deconstruct itself. Sticks violently assaults a nosy reporter, buries him neck-deep in the ground, and leaves him there. That reporter’s name? Michael DeForge. Things get more and more surreal — beyond even the everyday comic-strip surreality of a world with talking animals. A few pages feature recipes for impossible foods like “Classic Monterey Kebab,” which includes a fish scale, a twig, and a precious flower skewered on a stick and heated over flame. We learn about the mating rituals of shape-shifting birds. Visually, DeForge creates whole panels made out of abstract shapes, with non-narrative captions laid over the top. Some of the pages are just tone poems.

Everybody in the book suffers. Sticks Angelica is eaten by bugs: “I’m covered in bites, rashes, sores… even if I wanted to come back to the city, I’m marked.” Michael DeForge is eventually dug up from his hole in the ground, but his body has atrophied to the point where it’s as thin and light as paper, so he floats around like a ghost, haunting the forest animals. A goose is killed by smoke inhalation after it swallows a worm whole and the worm builds a cabin in its gut, which then burns down in a fire.

It’s true that thanks to the deterioration of comics pages in recent years, even strips as banal as Mark Trail have become weirder and more disjointed, but Sticks Angelica is something else again. It’s a newspaper comic strip that has been visited by several Biblical plagues and survived them all out of sheer spite. Everything about the book, from the art to the characters to the plot, is designed to confound its readers’ expectations. It builds comedy out of heartbreak and spins tragedy out of gag strips. Just when you thought you’d seen everything that could be done with eight boxes, a cast of talking animals, and a punchline, along comes a book like Sticks Angelica to remind you that the form can be endlessly refreshed.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Over the top

Every so often I'll read a corporate superhero comic that reminds me why I fell in love with the genre as a child. This week's U.S.Avengers #4 is that kind of a book.

Writer Al Ewing has been pubilshing fun superhero comics for Marvel for a while — his Ultimates has basically grown into a hall-of-fame of the weirdest ideas Marvel writers have ever produced — but his U.S.Avengers series is the best thing he's done yet. Starring the most half-baked collection of superheroes you can imagine — Squirrel Girl, an off-brand Hulk, a pacifist Iron Man — and illustrated with great sincerity by Paco Medina, the book feels like a parody that spins out of control, only to circle all the way back around to become a straightforward adventure comic again.

Every issue of U.S.Avengers has been a standalone story that, in any other series, would be blown out to six stultifying issues. But the most recent issue takes that concept literally: It's an entire four-issue corporate superhero comic crossover crammed into a single, normal-sized issue. And I mean that literally: every few pages, Medina draws another cover to a nonexistent series ("Monsters 'n Shield" is one) followed by another splash page with credits. The comic is made up of four tiny comics.

Medina's art is fantastic for this sort of thing. He perfectly captures the man-in-tights aesthetic, but his work is just cartoony enough to lend a slight satirical bent.

The story involves two characters I loathe — Deadpool and Red Hulk, who is like the regular Hulk only red, and an asshole — trying to fight a monster-making mad scientist. Ewing gets credit for writing the only Deadpool line that has ever made me laugh out loud (and yes, I'm including the wildly overrated Ryan Reynolds movie in this estimation.) It's a ridiculous book starring ridiculous characters who know how ridiculous they are, which is all most of us ask from our superhero comics.

In a time when most monthly corporate comics are overridden with crossovers and bloated stories designed to pad out trade paperbacks, U.S.Avengers #4 openly mocks both those conventions. Maybe mainstream comics have lowered my expectations too much, but right now that's enough to win my heart.

Thursday Comics Hangover: My favorite thing is My Favorite Thing Is Monsters

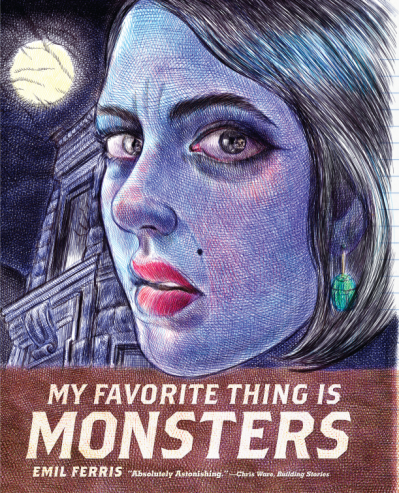

You've likely read something in the last month about Emil Ferris's stellar graphic novel My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, which was just published by Fantagraphics Books. NPR's John Powers explains the story of how Ferris came to create the book:

She was a 40-year-old single mom who supported herself doing illustrations when she was bitten by a mosquito, she contracted West Nile virus, became paralyzed from the waist down, and lost the use of her drawing hand. Fighting chronic pain, she taught herself to draw again, then reinvented herself as a graphic novelist, spending six long years creating what's clearly an emotional autobiography.

It's a remarkable story, and Monsters is a remarkable debut. It tells the story of Karen Reyes, a monster-obsessed young woman in 1960s Chicago who investigates the murder of her upstairs neighbor, a Holocaust survivor named Anka. Karen imagines herself as a monster — a human eternally transitioning to a werewolf.

It will take you a while to get into the plot, though, because the art is unbelievably, distractingly good. Ferris is a world-class illustrator. Using what appears to be colored pencils on lined three-ring binder paper, Ferris replicates classic works of art and dreams up pulpy sci-fi/fantasy/horror magazine covers and renders startling portraits of characters. Those portraits are the most astounding part of the book. There is life behind these faces. These eyes are more than ink on paper: they're judging you, imploring you, seeing you.

You've never seen comics like this. The art of Monsters relies on a blend of comics techniques: some pages use the traditional panels-and-word-balloons of American comics, but many of the layouts blend words and pictures in new ways — dreamy montages with narration spooling out in margins, blocks of brief essays interpolated in full-page illustrations, double-page spreads of fever-dream faces appearing in the wood paneling of an ugly apartment.

Monsters feels to me like a once-in-a-generation debut — a vision so clear and original that it will change the course of cartooning. Ferris's book lands with the force of a Chris Ware or a Robert Crumb. Newcomers to comics will be consciously and unconsciously emulating her style and storytelling techniques for decades to come.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Villains are not anti-heroes

Last week, Fernando Alfonso III wrote at the Lexington Herald Leader:

An Eastern Kentucky police chief has removed large decals with the Punisher skull and “Blue Lives Matter” from eight police cars after a backlash following the publication of a Herald-Leader story.

The Catlettsburg Police department, which employs eight full-time and two part-time officers for a population of about 2,500, featured the images on the hoods of its 2013 and 2017 Ford Interceptor sedans and sport-utility vehicles, assistant police chief Gerry Hatzel said. The stylized skull was from “The Punisher” comic book series.

The Punisher, of course, is a mass murderer. Created in the 1970s as a pastiche of the gritty Death Wish and Dirty Harry films, the character murders criminals without any semblance of a fair trial. He considers himself to be a soldier, but he works alone, without any commanding officers to keep him in line. He answers to no one. He is, in short, not a role model for police officers.

When comics writer Mark Waid argued that the Punisher is a villain, a number of Twitter users fansplained to him that the Punisher is an “anti-hero”. “[H] e IS one of the good guys. He's an anti-hero. As a comic book writer, you should know the difference,” one person told Waid. Another lectured the comics veteran, “Learn your terms before using them.”

For thirty years, superhero comics have continually blurred the definition of “anti-hero” to the point where it now basically means “protagonist.” A mass-murderer is not an anti-hero; a mass-murderer is a villain. An anti-hero is a character who reluctantly upholds noble causes or otherwise behaves in a courageous manner that is against type. (As another Twitter user explained during the Punisher discussion, Luke Skywalker is the hero of Star Wars, while Han Solo is an anti-hero and Boba Fett is the villain. This is a pretty good rule of thumb.)

This confusion is a trend that can be traced back to the days when the Punisher, who started as a villain in Spider-Man comics, first starred in his own mini-series. It’s a confusion as old as kids misreading Rorschach as the hero of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen, when in fact he’s intended as a horrific parody of cartoonist Steve Ditko’s Objectivist leanings. It’s what happens when 13-year-old boys read Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns as a cool Batman story instead of a parable about the creeping fascism of the Reagan era.

Of course, this isn’t a problem that’s exclusive to comics. Blockbuster movies have had a hard time identifying heroes for the last 40 years or so. But comics have been singularly obsessed with heroism for almost a century now, and so the problem seems more egregious within comics somehow.

And I’m not saying that every fictional story needs to center on a hero who unfailingly commits good works. But the fact that fandom that can’t recognize the difference between an anti-hero and a villain is troubling. And the fact that police — people who swear to protect and serve the American public — celebrate the logo of a murderer should be worrying to everyone.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Can you top this?

The eighth issue of Nick Spencer and Steve Lieber's crime comic The Fix was published yesterday, and this series keeps getting better. Ostensibly the story of two crooked Los Angeles cops and a drug-sniffing dog named Pretzels, The Fix keeps expanding to absorb more and more characters; what began as a character-focused heist story quickly (and effortlessly) became a huge ensemble piece.

Note those words: "expanding," "huge." This isn't the vocabulary you usually use to describe an Elmore Leonard riff. What wasn't apparent in the clever first issue of The Fix is that it's a shaggy dog story, a dirty-joke-riddled tall tale whose stakes are raised with every chapter. The reveal in the eighth issue is the biggest yet, and it leaves me wondering if eventually the threats in the book will have to transcend the semi-realistic sleazy LA noir genre to become intergalactic in scope.

Spencer's script is wry and character-driven. One of the two leads prays to God for a favor and apologizes for being out of touch for so long by saying "in Catholic school, they made it pretty clear it was you or masturbation, and I just--I got stuck with the home team, you know?" That is a lot of information about the character concealed within a gag that we didn't previously have before. A rule of thumb for reading a crime story: when a joke advances the plot, that's good writing.

From the wordless sequence depicting Pretzel's origin story that opens the issue to a series of pratfalls as a character tries to climb a fence that's too tall for him, Lieber's art is perfect for this kind of comedy. His figures and facial expressions aren't exaggerated in the least — he plays the characters straight, which makes the physical comedy and the quick stabs in the script land with even more force.

I have to wonder if The Fix might read better in collected trade editions than in single issues: while each issue feels like a contained chapter in a story, it could be easier to retain a sense of continuity when you read a bunch of chapters all at once. But no matter how you take it in, The Fix is a must-read: a funny, nasty, character-driven crime drama that keeps outdoing itself with every twist.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Thick as Thieves hits the streets

I couldn't make it out to the Thick as Thieves launch party last Sunday night at Brainfreeze in the old Lusty Lady building, but copies of the first official issue of Thick as Thieves have started to make their way through the city. You should pick one up.

I told you about the proof-of-concept issue of Thick as Thieves back in November. Basically, it's a free comic newspaper in the vein of Intruder, featuring Seattle-area cartoonists doing whatever they want for one full page per cartoonist. The issue just hitting stands this week is end-to-end entertaining.

The MVP of Thick as Thieves issue one is Seattle cartoonist Marie Hausauer, who recently published a terrific comic book about a dead raccoon. Hausauer contributes the cover for the issue, a beautifully rendered piece that resembles the work of Jason Lutes, and she illustrates the best, funniest strip in the issue, about a woman whose boyfriend undergoes a horrific transformation. (I don't want to tell you any more than that because the joke is too good.)

Other standout comics in the issue include an ode to skirts by Whitney Stephens, a great and gory comic strip offering a cathartic Donald Trump moment by Katie Wheeler, a great gag about a seemingly indefatigable customer service rep by Ben Horak, and a fantastic action strip by Marc Palm that has to be a contender for the (nonexistent) 2017 Award for Best Final Panel in a One-Page Strip.

A couple of pages in Thick as Thieves are uneven, but that's to be expected in an anthology. But the good far outranks the bad, and the increase in quality between the first test-run issue and this first official issue indicates that Thick as Thieves could eventually outstrip Intruder if editors Simon Lazarus Vasta and Ryan Tiszai continue on this learning curve.

Warren Ellis's later comics work hasn't done it for me. Even the stuff that most people dig, like Trees and Injection, have just felt like late-stage Ellis to me, which is to say it feels kind of like self-parody: people behave like bastards; they say outrageous things in a condescending tone; some giant threat vaguely makes itself known; finally, everything collapses into a highly unsatisfying ending. Nothing of Ellis's since Planetary has really worked.

To be honest, I'm not sure why I gave the first issue of The Wild Storm the time of day. It's a reboot of Jim Lee's awful Wildstorm superhero universe, which has never really interested me. But the only good Wildstorm comics were Ellis's — particularly his Authority and Planetary, which are the source code for pretty much every superhero comic published in the last decade and a half. The thought of Ellis returning to these comics to restart them with a clean slate seemed like a mammoth mistake. I guess I wanted to gawk at a car crash.

The car crash didn't happen. The Wild Storm is easily Ellis's best mainstream work in a while. It's dialogue-heavy, and a few of the characters aren't immediately unlikeable, which is a refreshing change of pace. You won't find any of Jim Lee's ludicrous costume designs here, and the characters are barely recognizeable; only their awkward insistence on being called by their superhero names — Zealot, Voodoo, etc. — ties them back to the old Image Comics days.

I don't know if The Wild Storm will hold up. It's scheduled to run for 24 issues over two years, and Ellis has proven that he's pretty bad at marathons, to say nothing of his inability to end a damn project in a satisfying way. But it's a promising start, at least.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Product of the 80s

Early in Sexcastle, a random goon threatens Shane Sexcastle by asking, "You ever hear the phrase 'You brought a knife to a gun fight?'"

Sexcastle responds, "This is worse than that. You brought a you to a me fight."

Sexcastle was first published almost two years ago, but it had escaped my attention until the good folks at Phoenix Comics turned me on to it last night. I was interested in an upcoming comic called Rock Candy Mountain about a hobo’s epic journey by a cartoonist named Kyle Starks, and they happened to have his first book in stock. It’s pretty fantastic.

Shane Sexcastle, the star of Sexcastle, is basically the protagonist of the world’s biggest 80s action movie — Patrick Swayze in Roadhouse blended with Kurt Russell in Big Trouble in Little China, and then garnished with basically everyone who ever starred in an Expendables movie. He’s trying to start a new life working for a single mom florist, but he keeps getting pulled back in to a circle of violence.

Sexcastle is not especially witty. It’s a comedy that revels in the over-the-top violence of 80s action movies, but it doesn’t have the slyness or the critical eye of, say, Punch to Kill. It’s a fan’s celebration of a particular genre, and though Starks is a brilliant cartoonist — he can squeeze more action onto a single page than most Marvel Comics artists can fit into a single issue, and he can make it easier to follow besides — he’s not especially complex with the writing.

And that’s okay. Sexcastle doesn’t need to be deep. It’s funny and it’s imaginative and it’s expertly put together. On an otherwise slow week at the comics shop, that’s more than enough to win my allegiance.

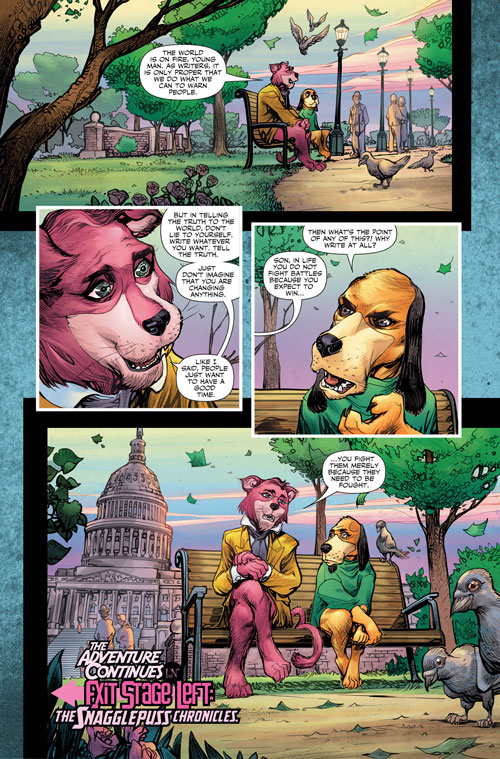

Thursday Comics Hangover: The soul of Snagglepuss

I have written about how good the Flintstones comic is, but it has to be noted that the most recent issue, #8, is the best, most ambitious edition yet. It satirizes gender roles, economics, politics, and celebrity, and it also contains a great little story about how the ultimate goal of parenting should be to fuck the next generation up slightly less than your own.

My favorite part of the new issue is when a guest speaker named "Thorstone Pebblen" discusses "a brand-new field of research called 'economics.'" He explains it thusly: "When you trick somebody into participating in a small-time fraud, it's called a 'scam.' But when the scam is so big that people have no choice but to participate, it's called 'economics.'"

While underrated artist Steve Pugh is doing incredible work balancing the many tone considerations of the book, a vast share of the credit for this comic's success has to go to writer Mark Russell, who is somehow simultaneously paying homage to the old Flintstones cartoon's history of social satire while also forging his own path.

And then two days ago, Russell revealed in an interview with HiLoBrow that he's reimagining the Hanna Barbera cartoon character Snagglepuss as "a gay Southern Gothic playwright."

I envision him like a tragic Tennessee Williams figure; Huckleberry Hound is sort of a William Faulkner guy, they’re in New York in the 1950s, Marlon Brando shows up, Dorothy Parker, these socialites of New York from that era come and go.

This news spread on Twitter, but I couldn't quite believe it was true. It sounded too good, right? It had to be a joke, right?

Not so much. Yesterday afternoon, DC Comics released a page from the upcoming Snagglepuss comic, with art by Howard Porter. Click to enlarge this:

In the HiLoBrow interview, Russell calls Snagglepuss "very different from The Flintstones, it’s more about the creative process; much more of an intimate story." If he pulls this one off, Russell is going to be one of my favorite contemporary comics writers. In an ever-churning content world of reboots and reimaginings, he's doing the unthinkable: he's taking exhausted corporate IP and making it more personal, more thoughtful, and more relevant.

Thursday Comics Hangover: You maniacs! You blew it all up!

Jack Kirby's Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth was my favorite childhood comic. I didn't know it was a ripoff of the first Planet of the Apes movie at the time I started reading my brother's old issues. In fact, I probably started reading Kamandi a full decade before the first time I saw Planet of the Apes. And while I love the Apes reboot films, I still prefer Kamandi.

The premise of Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth is pretty much right there in the title: on a blasted-out apocalyptic earth — something called The Great Disaster happened an indeterminate amount of time ago — a human boy named Kamandi tries to survive. While Planet of the Apes just featured talking apes, Kirby populated Kamandi's planet with all kinds of talking humanoid animals: apes, yes, but also dogs, tigers, cheetahs, bears, and more.

Kirby packed Kamandi with all sorts of allegories for life in the 1970s — my favorite topical story involved a race of subterranean mole people who worship the Watergate tapes — but it was, primarily, a boy's adventure strip, a postapocalyptic sci-fi Jonny Quest.

Last week, DC Comics published something called the Kamandi Challenge Special, a squarebound sampler of Kamandi comics for $7.99. I've been waiting years for a nice, affordable sampler of these stories to give to the young comics fans in my life; I think Kamandi has a timeless quality that might appeal to any comics fan.

Unfortunately, this isn't the collection to pass on to a new comics fan. Frankly, the selection of comics in this edition is just plain weird. The book starts with a reprint of Kamandi #32, which is smack in the middle of an ongoing story involving a weird space organism that shifts from uni- to multi-cellular and back again. ("I am 'ME.' I can be...WE...! Now I am...US...!") It's a fun ride to be dropped in the middle of — one chapter is titled "Satan in the Sands," for crying out loud — but there's no real reason why it should be the story that opens the book.

Especially since the second book collected in the volume is the very first issue of Kamandi — one which introduces characters who we've already met in the first story. It's just a weird curation decision. And then the rest of the book consists of a black-and-white unpublished post-Kirby Kamandi story written by Jack C. Harris and drawn by Dick Ayers and Danny Bulandi which is itself wrapped around an unpublished Jack Kirby Sandman story that doesn't feature Kamandi at all.

Imagine you're just sitting down to watch a TV show. You've heard lots of good things about it. You're excited to watch it. But the first episode you watch is from the middle of the second season. Then you watch the pilot. And then you watch a shoddy clip show from a season well after the main actor has already left to launch his movie career. None of this makes any kind of goddamned sense, is what I'm saying.

If you're acquainted with Kamandi as a character but you haven't read much of his adventures, maybe the Kamandi Challenge Special would be worth picking up. It does feature, after all, a talking gorilla revolutionary named Ramjam. But anyone unacquainted with Kamand should stay far away from this awkward, poorly planned book.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Snow day

Not everyone realizes this, but every single comics store in the United States uses the exact same distributor: Diamond Comics Distributors. The collected graphic novels can be purchased directly through the publishers or through book distributors, but if you want to sell the staple-bound monthly so-called "floppies," you have to go through Diamond. There is no alternative. Diamond's last competitor, a distributor called Heroes World, was bought by Marvel Comics and then collapsed in the mid-1990s.

I bring this up because while Seattle is wet and relatively warm this week, we are surrounded on all sides by a horrifying snowscape. And the Diamond truck — the truck that carries every single comic headed to Seattle this week — can't get through the Pass. This means that no comic book store in Seattle had new comics yesterday.

It's really kind of batshit, if you think about it for a moment. If Diamond were to unexpectedly go out of business tomorrow, every comic book store in the country would be strangled for product. Dozens of shops would likely collapse within days, if not weeks, of Diamond's hypothetical closure.

Happily, while Diamond holds a monopoly on monthly comics distribution, they're not the only way for customers to get comics anymore. You can download them on your digital devices — although Comixology, the industry leader for digital comics, was bought by Amazon a while back, so you're basically trading one monopoly for another — and you can buy collected editions at your local independent bookstore. But it is very uncomfortable that all these hardworking small business owners in Seattle, many of whom have been in business for years, are reliant on one single truck making its way across a snowy mountain pass. There has to be a better model than this, is what I'm saying.

UPDATE 1/19/2017 at 1:14 pm: On Facebook, Short Run offers a terrific suggestion for a substitution for your weekly comics:

Visit Fantagraphics Bookstore and Gallery, Phoenix Comics and Games, Zanadu Comics, Elliott Bay Book Company, Left Bank Books Collective, and check out their LOCAL section.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Are you a Batman person or a Superman person?

I'm a Superman guy, not a Batman guy. Batman's fine — I've read plenty of Batman comics over the years — but ultimately Batman is about arrested development: any Batman story is basically a story of an emotionally stunted rich dude. There's only so much emotional wallowing you can do before you fall into parody. (I feel similarly about Trent Reznor: you can do a couple albums about the hurt in your soul, but after you make a couple critically acclaimed best-selling records, maybe you can afford a little therapy?) Will Arnett's portrayal of Batman from the 2014 Lego Movie spectacularly identified the character's ridiculousness, especially in this song:

Superman, on the other hand, is all about being an adult. I've written about what makes Superman an interesting character: internal conflict over complicated moral choices. Batman often can't withstand that kind of complexity.

But DC Comics recently released paperback collections of the first six or so issues of the 2016 Batman and Superman series, and I'll be damned if these two characters haven't flipped in my estimation: Batman is the more interesting, more adult character and Superman is caught in a tar pit of adolescent melodrama.

Let's be clear: Batman Vol 1: I Am Gotham isn't a transcendant superhero comic. Hell, it's not even the best superhero comic from writer Tom King to be released in the last year (that would be King's amazing Vision series, which added layers of depth to a weird tertiary Marvel Comics character.) But it is a hell of a lot of fun, with Batman facing down a pirate, a crashing 747, and a pair of superpowered heroes who want to make Gotham City a better place.

I Am Gotham deals directly with Batman's perennial Superman envy by introducing a team of heroes with Superman's power set but very little real-world experience. Most of the book consists of Batman trying to figure out if he can trust them, and whether he's been outclassed as hero of the city. King's Batman seems to be growing and changing: he's aware of his own flaws and he's actively trying to overcome them.

David Finch's art is not my favorite: everything looks a little too pinched, and heroes look a little too constipated. But here, Finch allows for more depth, introducing characters with different body types. His facial expressions could still use some work — so much grimacing! — but it's nice to see an established fan-favorite artist take on greater depth and range.

Speaking of depth and range, Superman Vol 1: Son of Superman delivers none. What a mess this comic is. It's unclear how much of this problem is due to writer Peter Tomasi and how much of it has to do with corporate edict. I can't even fully understand what's going on here.

So it seems that Superman is dead. But another Superman from a different timeline is seeking refuge in the dead Superman's timeline. This other Superman is married to Lois Lane (the one from his own timeline, not the one in the dead Superman's timeline) and has a child. This version of Superman is living in hiding, waiting for the dead Superman to come back to life. But eventually...

...oh, who cares? This book is just a bunch of flying and screaming and punching and angst, all signifying exactly nothing. It's too bad, too, because artist Doug Mahnke is one of the better Superman artists of our time: he can draw pretty much anything well: super-fights and morose graveside scenes and optimistic faces. But this story is all over the place, and not even Mahnke's remarkably solid art can provide a sense of consistency.

The one thing that Son of Superman does right is that it provides a great vision of Superman as a parent. His son with Lois, Jonathan, is basically a carbon copy of himself, only more reckless and more uncertain. This new character adds a new twist to the Superman formula: not only does he have to save the world, he has to raise a son while he's doing it. Being a parent makes Superman even more interesting. Too bad everything else about this Superman comic is so damn boring.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Vote for more superhero comics like this

By the end of 2016, I found myself completely disillusioned by corporate comics. Marvel Comics seem to be a neverending morass of recycled events and weird brand management choices. A few DC Comics titles are promising, but it seems as though getting comfortable there might be a mistake since the entire line will likely be rebooted as soon as sales drop low enough. These things happen in cycles, of course. A few years ago, Marvel was producing a bunch of work that transcended corporate dictates, and DC has had its moments over the last decade, too. I have faith that soon someone will break the cycle and make something worth reading again.

This election is between a smarmy Hydra agent (who Ms. Marvel calls “Chuck the Hydra hipster”) and a competent woman. The allegory for Clinton Vs. Trump is pretty on-the-nose for a corporate comic. Ms. Marvel travels around her beloved Jersey City, trying to recruit voters, but those voters are too apathetic to care. Moms are busy, crazy old cranks “haven’t voted since 1972” because they’re “protesting all the things,” and others believe that both candidates suck pretty much equally.

Because it’s a superhero comic, and because Ms. Marvel is thoroughly an optimistic work that believes the best of people, good triumphs over evil. That made Ms. Marvel a bitter pill to swallow in the weeks after the election, but this comic is already aging well. I read it now and think about what might have been had we seen a few more positive-hearted activists in the right places around the country. I read it and think that things can get better, and that democracy is worth the fight. It’s a superhero comic written from a personal, aspirational perspective, one that believes in a better world. Hey, DC and Marvel: more like this in 2017, please.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Women tell stories in order to live

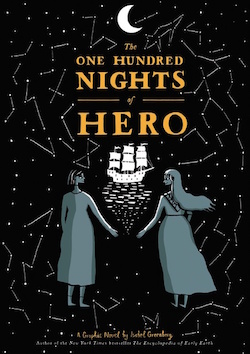

Last week, I was thoroughly disappointed by a comic book that was supposedly about the enduring power of stories. This week, I’m entirely enchanted by a comic that demonstrates the empowering endurance of stories. Isabel Greenberg’s hardcover comic The One Hundred Nights of Hero is a story about stories wrapped in other stories, including a Scheherazade scenario in which a woman must tell a story so compelling that it distracts a lecherous man from advancing on her, night after night.

Greenberg’s art is deceptively crude. On first glance a panel in which five sisters gather around a candle in the midst of an inky night looks as though it could be a woodcut, the lines are so primitive and scratchy. But look a little closer and you’ll see finer details. One sister’s hand is splayed out on the ground for balance, another’s finely wrought braid winds down her back.

Throughout the book, Greenberg shades scenes with splatters and sprays of ink that look at times like Jackson Pollock took control of the pen. But those sprays of ink aren’t mistakes. In fact, they serve to remind the reader that the story they’re reading is ink on paper, a happily primitive medium that Greenberg uses to great effect.

Many of these stories are about the enduring power of women, and the unthinking malevolence of men. (The moral of one story: “Men are false. And they can get away with it.”) In one story, a woman reveals to her husband that she can read by writing “I LOVE YOU” onto a fogged window; the illiterate man then concludes that his wife is a witch who has cursed him with a magical spell.

These women revel in words and stories and books:

They read aloud to each other, they wrote great, swirling sentences in ink and charcoal, in mud and paint and pencil. They luxuriated sinfully in that most beautiful of all things: The written word.

These stories do not all have happy endings, but they are all meaningful tributes to smart women who persevere even when the entire world conspires against them. These are stories of gods and sailors and lovers and, most importantly, sisters. It’s a never-ending puzzle box of stories about stories, and the important role that women play in keeping stories alive for future generations. This is a book that will teach you how to fall in love with books again.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A library full of empty books

One Week in the Library comes in a format that doesn’t get enough play in comics shops: a ten dollar “graphic novella” that tells a single story from beginning to end. It’s a great format — not quite long enough to be a full-sized graphic novel, but longer than your standard monthly comics issue. More cartoonists should work at this size; it’s a great length for the medium.

Unfortunately, One Week at the Library isn’t the best advertisement for the format. By which I mean it’s a bad book. Written by W. Maxwell Prince and illustrated by John Amor, Library is the story of a librarian who works, alone, in an imaginary library. (“…the SAD ENCYCLOPEDIAS are in the Happy Corridor, which also houses the MISERY CHRONICLES, which themselves are part of THE SERIES OF IMPOSSIBLE JOY.”) The book is divided into seven chapters — one for each day of the week — and each chapter employs a different formal technique: one chapter tells a story in diagrams, another is prose, another is wordless, and so on.

You’ve seen this before. Library feels kind of like a Sandman knockoff, a story about the power of stories. But unlike Sandman, the stories never really grow beyond their concepts. They’re stories about stories for the sake of stories, and they just sort of sit there on the page, all vapid flash and shallowness.

Toward the end of the book, Prince writes himself into the story and frets over whether the reader will think he’s smart. To which I reply: if you want a reader to think you’re smart, maybe don’t quote Doors lyrics in your story. And a book about the depth and breadth of libraries should feel as though it was written by someone who has explored those depths. The literary references in Library are facile (Charlotte’s Web and Lewis Carroll get repeated shout-outs) and the library conceit disappears entirely at various points.

The Prince character self-consciously acknowledges the many comics writers who have appeared in their own books in the past, including Grant Morrison, and he whines that “I’m suffering a ton of anxiety that someone reading this will think I’m being lazy or derivative.” Unfortunately, simply acknowledging a critical complaint in a story isn’t enough to disarm that complaint, and writing a book about books isn’t enough to inspire warm literary feelings in a reader. The books in this library feel strangely empty of value.

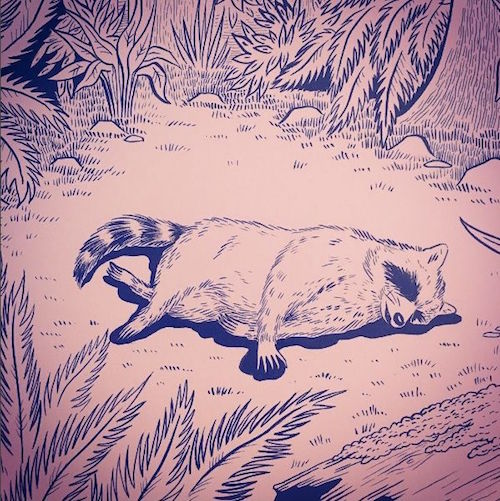

Thursday Comics Hangover: The dead mammal

I can't stand raccoons. With their tiny little hands and the way they clamber, brazen and unafraid, into human spaces, they unsettle me in a way that no insect or snake ever could. There is just enough human in raccoons to be recognizeable, but just enough snout and fang and fur to make them alien. A live raccoon sighting will always raise my hackles, and raccoon corpses by the side of the road have never invoked my sympathy.

Seattle cartoonist Marie Hausauer's new book Raccoon centers around a dead raccoon in the middle of the woods. For the first few pages, the "camera" slowly pulls back from the racoon corpse. It's lying on its side, almost human in repose, its legs crossed demurely, one front paw extended out further than the other, as though reaching for something. Its eyes are closed, hidden behind the creepy black band of fur that masks the eyes like a cartoon burglar. It's impossible for anyone — even a lifelong raccoon hater like myself — to not feel sad for the critter.

Eventually, it rots. Its ribcage juts out of a gaping hole in its chest. The uglier the raccoon corpse gets, the more vivid its surroundings become. All around it, ferns and trees and grass grows in a circle, creating a kind of spotlight with the raccoon in the center.

And then come the people. Three sets of humans encounter the corpse, dealing with it in different ways. The first party is a group of adults who are complaining about kitchen remodel projects. "Looks like he died snarlin'," the guy in the hiking boots and the ugly floppy outdoorsman hat says as he crouches by the body. They complain a lot about the smell. Next, a group of teenage boys walk through, and then a moody young woman.

This is a book about death, and grieving, and morbid curiosity. No person who encounters the raccoon responds in exactly the same way as any other person. The reader observes them all, as though we're lurking back in the shady woods, hanging back and passively taking note of their reactions.

Raccoon demonstrates a terrific balance between words and images: the book is respectfully silent in its beginning and closing (death is traditionally a very quiet thing), and the human dialogue fades in and out, like happening upon snippets of conversation in the woods as people walk past you on the trail. The banality of hearing people complaining about their kitchen remodels in the midst of nature's baroque grandeur makes everything seem a little less important.

With Raccoon, Hausauer continues to rapidly grow and deepen as an artist. This is a confident literary work — it's easy to imagine a Carveresque story about these teenage boys, for instance — from a writer who's finding her voice. Raccoon's realism falls comfortably within the continuum of Northwest fiction. It feels like a story that could only spring from our part of the world, with its lush green backdrops and its brazenly invasive wildlife. You've seen the title character of this story rooting around in your trash. You've maybe even wished death upon it. This, Hausauer says, is what happens next.

(Raccoon is available for sale now at Fantagraphics Bookstore, Arcane Comics, Push/Pull, and Left Bank Books.)

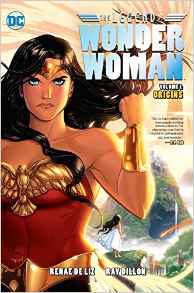

Thursday Comics Hangover: Another new start for Wonder Woman

The big problem with Wonder Woman, the reason why the character has had a hard time taking hold, is that DC Comics keeps restarting her from scratch. I can't keep track of how many times I've seen the Wonder Woman character rebooted and relaunched. Sure, other DC mainstays like Batman and Superman tend to wallow in retellings of their origin stories, but those stories never seem to change as much as Wonder Woman's.

Batman's parents always get shot. Superman's always rocketed from the planet Krypton into a field in Kansas. But Wonder Woman? Seriously, who the hell knows what's going on with Wonder Woman? Her origin has been retold with varying levels of camp and seriousness and pretentiousness many times over the years, and so as a result it's all become a kind of narrative static.

Or at least, that's what I thought. But I just read another retelling of the Wonder Woman origin story, in the form of a hardcover collection called The Legend of Wonder Woman Volume 1: Origins by Renae De Liz and Ray Dillon, and it's the first Wonder Woman story that's kept my attention in years.

Legend is an all-ages-friendly retelling of the Wonder Woman story set during World War II. De Liz's art is dynamic and manga-influenced, which is perfect for the unique blend of mythology and historical detail that Wonder Woman demands. You won't find the rippling abs of modern superhero comics here; De Liz's figures are dynamic, but not over-idealized.

The story takes its sweet time to unfold. We start with a young Amazonian princess named Diana who is trying to figure out her place in the world, and more than half the book passes before her costume makes an appearance. Tonally, Legend makes a major shift at the halfway mark. The first part of the book is more like a young adult novel featuring a pensive lead who isn't sure if she should embrace her legacy, and the second half is a straightforward origin story with all the comedy and economy of a lively animated film.

These two tones might feel out of place were it not for the main character. Diana is a terrific protagonist. She doesn't demonstrate the ridiculous aw-shucks humility of Clark Kent or the dull perfection of Bruce Wayne. Instead, she's a quiet observer with a strong sense of right and wrong. She feels duty-bound to act, but she's equally duty-bound to make sure that her actions are the right ones. Without the first half of the book to establish Diana's thoughtfulness, the second half wouldn't be nearly as much fun.

Until The Legend of Wonder Woman, I didn't have a Wonder Woman comic that I could unhesitatingly give to a girl looking for an introduction to the character. Now I do: she's a strong female lead who's smart, interesting, and she beats the stuffing out of Nazis. What's not to love?